Abstract

Background

Giant basal cell carcinomas (GBCCs), (BCC ≥5 cm), are often painless, destructive tumors resulting from poorly understood patient neglect.

Objectives

To elucidate etiopathogenic factors distinguishing GBCC from basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and identify predictors for disease-specific death (DSD).

Methods

Case–control study examining clinicopathologic and neuroactive factors (β-endorphin, met-enkephalin, serotonin, adrenocorticotropic hormone, and neurofilament expression) in GBCC and BCC. Systematic literature review to determine DSD predictors.

Results

Thirteen GBCCs (11 patients) were compared with 26 BCCs (25 patients). GBCC significantly differed in size, disease duration, and outcomes; patients were significantly more likely to live alone, lack concern, and have alcoholism. GBCC significantly exhibited infiltrative/morpheic phenotypes, perineural invasion, ulceration, and faster growth. All neuromediators were similarly expressed. Adenoid phenotype was significantly more common in GBCC. Adenoid tumors expressed significantly more β-endorphin (60% vs. 18%, P = 0.01) and serotonin (30% vs. 4%, P = 0.02). In meta-analysis (n ≤ 311: median age 68 years, disease duration 90 months, tumor diameter 8 cm, 18.4% disease-specific mortality), independent DSD predictors included tumor diameter (cm) (hazard ratio (HR): 1.12, P = 0.003), bone invasion (HR: 4.19, P = 0.015), brain invasion (HR: 8.23, P = 0.001), and distant metastases (HR: 14.48, P = 0.000).

Conclusions

GBCC etiopathogenesis is multifactorial (ie, tumor biology, psychosocial factors). BCC production of paracrine neuro-mediators deserves further study.

Keywords: neglect, basal cell carcinoma, giant, locally advanced, metastatic, analgesia, pain, innervation, neurofilament, β-endorphin, proopiomelanocortin, met-enkephalin, serotonin, ACTH, survival

INTRODUCTION

Nonmelanoma skin cancers, including basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), constitute the most common malignancy in the United States.1,2 The incidence of BCC has been increasing for many years, likely because of a combination of greater sun exposure and longer life expectancies.1–3 In general, BCCs show a clinical course that is characterized by painless slow growth, little to no propensity for metastasis, and a high cure rate.4,5 Tumor size greater than 1.0–3.0 cm is considered a marker of aggressiveness.6,7 Giant basal cell carcinoma (GBCC) is a rare variant, defined as BCC ≥ 5 cm in dimension.8 GBCCs exhibit clinically aggressive behavior characterized by deep local tissue invasion as well as local recurrence and metastasis7,9 in 38% of patients, and a 62% cure rate at 2 years follow-up.10 Approximately, 1% of all BCCs attain a size of 5 cm or greater11 with the true prevalence likely lying between 0.4% (5/1093)12 and 2.3% (22/967).13

The pathogenesis of GBCC and the prevalence of neglect in patients are multifactorial. Failure to seek treatment may be the consequence of psychologic, socioeconomic (ie, poverty and insurance status14,15), and potentially tumor-specific characteristics such as lack of pain13,16–18 (see Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A42). GBCCs are rarely painful, even with deep tissue invasion, which may in part account for patient neglect.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of giant basal cell carcinomas and controls.

| Giant BCC (N=11, T=13) | Control BCC (N=25, T=26) | P-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 4F:7M (1:1.75) |

10F:15M (1:1.5) |

0.84 |

| Age* | 73.9±6.3 (64–84yrs) |

69.6±12.5 (49–85yrs) |

0.29 |

| Site | HN: 9/13 (69%) Trunk: 2/13 (15%) Ext: 2/13 (15%) |

HN: 15/26 (58%) Trunk: 9/26 (35%) Ext: 2/26 (8%) |

0.40 |

| Skin cancer history | 3/10 (30%) | 14/23 (61%) | 0.10 |

| Alcoholism | 4/8 (50%) | 0/12 (0%) | 0.006 |

| Patient lives alone | 7/9 (78%) | 3/14 (21%) | 0.008 |

| Patient concerned | 1/9 (11%) | 16/22 (73%) | 0.002 |

| Anemia | 3/5 (60%) | 4/11 (36%) | 0.38 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 2/4 (50%) | 2/10 (20%) | 0.26 |

| Duration* | 115.3±77.5 (13–240mo) |

26.8±42.1 (1–180mo) |

0.000 |

| Diameter* | 9.6±4.4 (5–20cm) |

1.6±1.3 (0.2–4.5cm) |

0.000 |

| Outcome | FU*: 9.5±16.6 (0–48mo) DOD: 5/8 (63%) AWOD: 3/8 (38%) |

FU*: 13.6±12.7 (0–35mo) DOD: 0/23 (0%) AWOD: 23/23 (100%) |

0.000 |

Results reported as mean ±standard deviation (range).

P values: significance at <0.05.

BCC: basal cell carcinoma; N: number of subjects; T: number of tumors; AWOD: alive without disease; DOD: died of disease; Ext: extremity; FU: follow up time; HN: head and neck; mo: months; yrs: years.

Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure, the major cause of BCC,19 stimulates the synthesis of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) in skin, the precursor of POMC peptides including adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and β-endorphin.20–23 It has been shown that UVR stimulates β-endorphin expression in the skin and serum,24,25 which may lead to increased pain thresholds and generates addiction to UVR in rodents.26 Moreover, both β-endorphin and ACTH are expressed more prominently in skin tumors including BCC than in normal skin.27–30 The skin also expresses proenkephalin, a precursor of opioid peptides including met-enkephalin, a growth-modulating and analgesic peptide with important roles in skin physiology.31–34 Epidermal keratinocytes can also produce serotonin, a neurotransmitter with impacts on mood and behavior,35–38 and respond to it in an autocrine or paracrine fashion.36,39,40

In light of these observations, it was hypothesized that “tumor addiction,” defined as a compulsion toward tumor neglect despite negative consequences, may represent an entity mirroring behavioral addictions.41 Because the role of neuromediators including serotonin and opioids is increasingly implicated in the pathophysiology of behavioral addiction,41–43 this study investigated whether neglect in GBCC is accompanied by increased cutaneous expression of β-endorphin, serotonin, met-enkephalin, and ACTH. More aggressive BCC subtypes demonstrate decreased expression of neurofilament and markers of neuronal differentiation.44,45 As such, the possibility of decreased tumor innervation in GBCC as another source of tumor analgesia was investigated. A systematic review to define clinicopathologic characteristics associated with GBCC and independent predictors for disease-specific death (DSD) in patients with GBCC was also performed.

METHODS

Case–Control Study

Patient Selection

Thirteen GBCCs (11 patients), defined as a single tumor ≥5 cm, were retrospectively identified from 1998 to 2014. Twenty-six control cases (25 patients) of BCC >1 and <5 cm were consecutively selected for comparison. Tumor sizes were rounded to the nearest whole number (for all tumors in this study). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Albany Medical Center.

Clinical and Pathological Evaluation

Clinical characteristics including age, sex, alcoholism, anemia, hypoalbuminemia, patient concern, presence/absence of pain, tumor location, diameter, duration, and survival status were retrieved from medical records. Pathologic review confirmed diagnosis, histological subtype, presence of adenoid features, keratinization, pigmentation, perineural invasion, inflammatory host response (graded as absent, nonbrisk, or brisk), ulceration, and extent of invasion of surrounding structures.

Immunohistochemistry

Expression of neurofilament (Dako; 1:100), ACTH (rabbit monoclonal antibody; Harbor-UCLA, Torrance, CA), β-endorphin (rabbit monoclonal antibody; Harbor- UCLA), met-enkephalin (goat polyclonal antibody; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and serotonin (SPM 146; Abcam) was assessed by automated methods (Ventana Medical Systems Inc, Tucson, AZ). Expression was graded as present or absent. Intensity of expression was graded semiquantitatively on a scale (0 = absent, 1/+ = weak, 2/++ = moderate, 3/+++ = intense). Labeling index was defined and recorded as number of cells with positive expression per 100 cells counted. Presence of intratumoral and peritumoral neurons was assessed by recording expression of neurofilament as absent or present.

Literature Review

The term “giant basal cell carcinoma” was used to search the PubMed database up to April 11, 2014, with review of all study titles. Abstracts and full-text articles were reviewed when potential for inclusion was equivocal from title/abstract alone. References for included studies were reviewed to find additional sources. Cases where tumors transformed into a BCC from a different histological malignancy were excluded from review, as were tumors smaller than 5 cm. Where possible, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) sixth and seventh edition schemes were determined based on patient/tumor characteristics reported.

Statistics

The software STATA version 11.1 (College Station, TX) was used for all descriptive statistics. χ2 and Student t test were used for dichotomous and continuous variables, respectively. Univariate linear regression was used in graphing tumor growth rates. The software IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 (Armonk, NY) was used for all survival statistics. Length of last follow-up was used as the time variable and survival status “died of disease” as the event variable. The log-rank statistic was used for testing equality of Kaplan–Meier survival distributions. Univariate and multivariate Cox regressions were performed. For multivariate analysis, variables (excluding AJCC and treatment variables) with n >150 were included in the model, and stepwise conditional (entry P = 0.05, removal P = 0.10) backward elimination was used to compute the final model. Significance for all tests was set at P <0.05.

RESULTS

Case–Control Study

Clinical Characteristics

Supplemental Digital Content (see Table 2, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A43) (Fig. 1, see Figs. S1–S5, Supplemental Digital Contents, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A34–http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A38). GBCC and BCC were both more common in men than in women (1.5–1.75:1), and most commonly involved the head and neck (GBCC 69%, BCC 58%). The mean age of patients at diagnosis was also similar (70–74). There was no difference in the 2 groups in the presence of skin cancer history, anemia, or hypoalbuminemia.

Table 2.

Pathologic and immunohistochemistry characteristics of giant basal cell carcinomas and controls.

| Variable | Giant BCC | Common BCC | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| BCC, dominant subtype* | |||

|

| |||

| Morpheic/micronodular | 5/13 (38%) | 2/26 (8%) | 0.012 |

| Invasive/Infiltrative | 6/13 (46%) | 6/26 (23%) | |

| Nodular | 2/13 (15%) | 17/26 (65%) | |

| Superficial | 0/13 (0%) | 1/26 (4%) | |

|

| |||

| Adenoid | 7/13 (54%) | 3/26 (12%) | 0.004 |

|

| |||

| Keratinzing | 5/13 (38%) | 8/26 (31%) | 0.631 |

|

| |||

| Pigmented | 0/13 (0%) | 6/26 (23%) | 0.060 |

|

| |||

| Perineural invasion | 4/13 (31%) | 1/26 (4%) | 0.018 |

|

| |||

| Host response (inflammation) | |||

|

| |||

| Absent | 4/13 (31%) | 8/26 (31%) | 0.143 |

| Non-brisk | 8/13 (62%) | 9/26 (35%) | |

| Brisk | 1/13 (8%) | 9/26 (35%) | |

|

| |||

| Ulceration | 13/13 (100%) | 8/26 (31%) | 0.000 |

|

| |||

| Peritumoral nerves by NF | 4/11 (36%) | 7/23 (30%) | 0.730 |

|

| |||

| Intratumoral nerves by NF | 2/11 (18%) | 4/23 (17%) | 0.955 |

|

| |||

| ACTH expression | 2/12 (17%) | 8/26 (31%) | 0.359 |

|

| |||

| Intensity | 2 + | 7 +, 1 +++ | 0.592 |

|

| |||

| ACTH LI | 3±9% (0–30%) | 2±5% (0–25%) | 0.703 |

|

| |||

| Serotonin expression | 3/12 (25%) | 1/25 (4%) | 0.054 |

|

| |||

| Intensity | 2 +, 1 +++ | 1 + | 0.129 |

|

| |||

| Serotonin LI | 1±2% (0–5%) | 0.2±1% (0–5%) | 0.143 |

|

| |||

| Beta-endorphin expression | 5/12 (42%) | 6/26 (23%) | 0.240 |

|

| |||

| Intensity | 4 +, 1 ++ | 5 +, 1 ++ | 0.496 |

|

| |||

| Beta-endorphin LI | 10±19% (0–50%) | 9±24% (0–75%) | 0.887 |

|

| |||

| Met-enkephalin expression | 11/12 (92%) | 23/24 (96%) | 0.607 |

|

| |||

| Intensity | 7 +, 3 ++, 1 +++ | 10 +, 10 ++, 3 +++ | 0.691 |

|

| |||

| Met-enkephalin LI | 39±35% (0–90%) | 56±35% (0–90%) | 0.170 |

Highest grade subtype identified, morpheic and micronodular subtypes were classified together as high-risk histologic subtypes. NF: neurofilament; LI: labeling index (# of positive cells/100 cells counted); + = weak, ++ = moderate, +++ = intense.

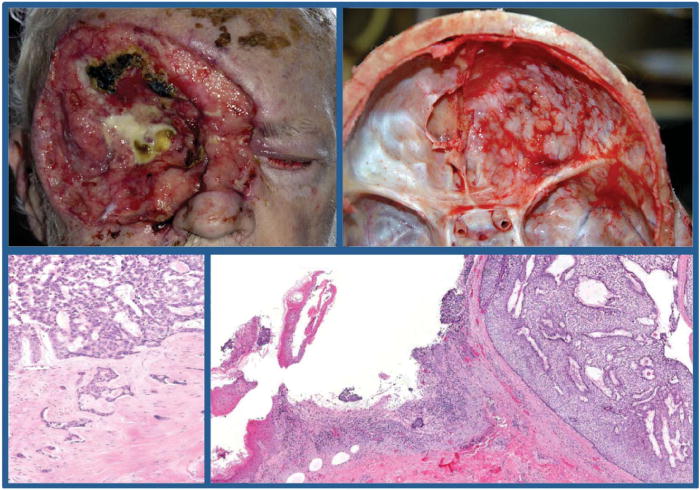

FIGURE 1.

Stereotypical giant basal cell carcinoma. Eight years after (complete) excision of a right orbital basal cell carcinoma, this 75-year-old male presented with a 10 cm in diameter giant basal cell carcinoma with extensive soft tissue and bone destruction including the right orbit and eye with extension into the dura mater (top left and right panels). He claimed discomfort but denied pain in the area and had no other symptoms or concerns. Because of general debilitation, surgical excision and radiation therapy were not pursued. He died 11 months later in hospice care. At autopsy, microscopic examination of the giant basal cell carcinoma showed mostly ulcerated nodular-adenoid pattern in the skin (bottom right panel) and nodular-adenoid and infiltrative pattern into cranium and dura mater (bottom left panel).

GBCCs were different from BCCs in several significant ways: duration of disease was longer (115 vs. 27 months, P = 0.000) and mean tumor diameters were larger (9.6 vs. 1.6 cm, P = 0.000). There were significant differences in several psychosocial markers between the 2 groups as well. Patients with GBCC were more likely to suffer from alcoholism (50% vs. 0%, P = 0.006), living alone (78% vs. 21%, P = 0.008) and were less likely to express concern (11% vs. 73%, P = 0.002). GBCC had a faster tumor growth rate than BCC (see Figs. S1 and S2, Supplemental Digital Contents, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A34 and http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A35). Although 63% (5/8) of patients with GBCC died of disease, all BCC patients were alive without disease (23/23) at last follow-ups (P = 0.000).

Histopathological and Immunohistochemistry Characteristics

Supplemental Digital Content (see Table 3, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A44) (Fig. 2). GBCCs were significantly more likely to demonstrate the aggressive histologic subtypes such as invasive/infiltrative (46%) and morpheic/micronodular (38%) compared with BCCs (P = 0.012). GBCC also demonstrated perineural invasion (31% vs. 4%, P = 0.018), ulceration (100% vs. 31%, P = 0.000), and adenoid features (54% vs. 12%, P = 0.004) more commonly than BCC.

Table 3.

Literature review of reported cases of giant basal cell carcinoma (n≤ 311; data derived from Supplementary File 1).

| Age (n= 311) | Median 68, mean 66.8 ± 12.8, range 23–96 years |

| Sex (n=311) | Males 188 (60.5%): females 123 (39.6%) [ratio 1.5] |

| Duration of disease before diagnosis (n=240) | Median 90, mean 111 ± 97.0, range 4–600 months |

| Patient characteristics (explicitly reported) (n≤311)* | |

| Lives alone | 12/311 (≥3.9%) |

| Anemia | 42/311 (≥13.5%) |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 17/311 (≥5.5%) |

| Alcoholism | 9/311 (≥2.9%) |

| History of other skin cancer | 42/227 (18.5%) |

| Multiple common BCCs | 39/228 (17.1%) |

| Multiple GBCCs | 17/265 (6.4%) |

| GBCC is recurrent BCC | 25/214 (11.7%) |

| Lesion reported to be painful | 22/115 (19.1%) |

| Superimposed infection | 36/118 (30.5%) |

| Site of involvement/invasion (n≤307) | |

| Head and Neck | 165/307 (53.8%) |

| Trunk | 93/307 (30.3%) |

| Extremities | 38/307 (12.4%) |

| Anogenital | 11/307 (3.6%) |

| Muscle invasion | 82/192 (42.7%) |

| Bone invasion | 102/253 (40.3%) |

| Dural invasion | 26/255 (10.2%) |

| Brain invasion | 13/255 (5.1%) |

| Orbit invasion | 38/253 (15.0%) |

| Lymph node metastases at presentation | 28/294 (9.5%) |

| Distant metastases at presentation | 32/294 (10.9%) |

| Tumor diameter (n=299) | Median 8, mean 10.7 ± 6.7, range 5–40 cm |

| Tumor area (n=297) | Median 48, mean 117.1 ± 166.3, range 10–1200 cm2 |

| Estimated rate of growth (diameter/duration) (n=235) | Median 1.1, mean 2.5 ± 3.5, range 0.2–20.8 mm/month |

| GBCC histologic subtype, highest grade reported (n=236) | |

| Superficial | 21/236 (8.9%) |

| Nodular | 87/236 (36.9%) |

| Invasive/Infiltrative | 101/236 (42.8%) |

| Morpheic | 27/236 (11.4%) |

| GBCC histologic features (n≤263) | |

| Adenoid pattern | 33/223 (14.8%) |

| Keratinizing | 25/233 (10.7%) |

| Ulceration | 147/239 (61.5%) |

| Perineural invasion | 21/263 (8.0%) |

| AJCC staging 6th/7th edition schemes (n=292) | |

| T2 | 35/293 (12.0%)/191/293 (65.2%) |

| T3 | 140/293 (47.8%)/44/293 (15.0%) |

| T4 | 118/293 (40.3%)/58/293 (19.8%) |

| N0 | 264/292 (90.4%)/264/292 (90.4%) |

| N1 | 28/292 (9.6%)/7/292 (2.4%) |

| N2a | NA/0/292 (0.0%) |

| N2b | NA/14/292 (4.8%) |

| N2c | NA/7/292 (2.4%) |

| M0 | 260/292 (89.0%) |

| M1 | 32/292 (11.0%) |

| Stage II | 162/292 (55.5%)/173/292 (59.3%) |

| Stage III | 95/292 (32.5%)/41/292 (14.0%) |

| Stage IV | 35/292 (12.0%)/78/292 (26.7%) |

| Follow up time (n=217) | Median 20, mean 27.8 ± 36.0, range 0–180 months |

| Treatment (n≤306) | |

| Excision | 229/306 (74.8%) |

| Mohs | 24/115 (20.9%) |

| Debulking | 11/306 (3.6%) |

| Chemotherapy | 21/306 (6.9%) |

| Radiation therapy | 67/306 (21.9%) |

| Amputation | 8/306 (2.6%) |

| Grafting | 127/303 (41.9%) |

| Major reconstruction/flaps | 85/303 (28.0%) |

| No treatment | 23/305 (7.5%) |

| Outcome (n≤295) | |

| Local recurrence | 59/258 (22.9%) |

| Lymph node metastases | 24/286 (8.4%) |

| Distant metastases | 29/295 (9.8%) |

| Survival Status (n=277) | |

| Alive with disease (AWD) | 32/277 (11.6%) |

| Alive without disease (AWOD) | 190/277 (68.6%) |

| Died of disease (DOD) | 51/277 (18.4%) |

| Died without disease (DWOD) | 4/277 (1.4%) |

Observations recorded as positive only if they were measured and explicitly reported. Thus, frequency listed is likely a marked underestimate. Patient characteristic variables “history of other skin cancer,” “multiple BCCs,” “multiple giant BCCs,” and “GBCC is recurrent BCC” were assumed to be (and coded) as negative if not explicitly reported to be positive in cases where other patient characteristics were detailed. The same assumption was not made for the variables “lives alone,” “anemia,” “hypoalbuminemia,” or “alcoholism.” AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.

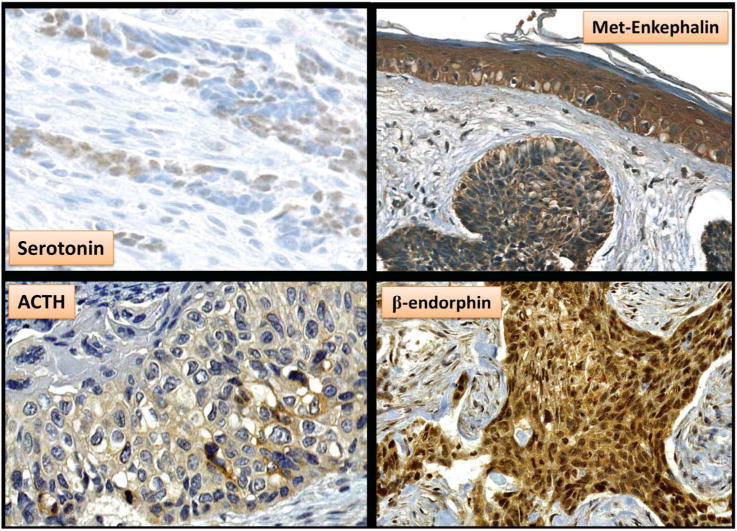

FIGURE 2.

Immunohistochemistry demonstrating cytoplasmic expression (brown chromogen) of mediators involved in analgesia by basal cell carcinoma tumor cells. Local production by basal cell carcinomas of the biogenic amine serotonin, the endogenous opioid met-enkephalin, and neuropeptides such as adrenocorticotropic hormone and β-endorphin may explain the clinical findings of analgesia. In addition, volumetrically larger basal cell carcinoma may produce larger doses of these mediators producing a systemic effect that promotes “tumor addiction” and mood alterations (ie, complacency and neglect).

There was no significant difference in the extent of inflammatory response or expression of intratumoral or peritumoral neurofilaments between GBCC and BCC. ACTH, serotonin, β-endorphin, and met-enkephalin were all expressed in both GBCC and BCC. Serotonin β-endorphin expressions were greater in GBCC (25% vs. 4%, P = 0.054 and 42% vs. 23%, P = 0.240) without reaching statistical significance. In all BCCs with adenoid histology, there was significantly increased expression of β-endorphin (60% vs. 18%, P = 0.01) and serotonin (30% vs. 4%, P = 0.02). Met-enkephalin was near universally expressed in GBCC (92%) and BCC (96%).

Literature Review

Three-hundred GBCCs identified from 146 publications combined with 11 cases from this series yielded 311 cases for analysis (see Table 4, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A45, see File 1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A48).

Clinicopathologic Characteristics

Median age of patients with GBCC was 68 (range 23–96) with a male to female ratio of 1.5. Median duration of disease was 90 months (range 4–600 months). Median tumor diameter was 8 cm (mean 10.7 ± 6.7, range 5–40 cm). The estimated rate of growth for tumors was calculated at a median of 1.1 mm/mo (mean 2.5 ± 3.5). The most common sites of tumor involvement were the head and neck (53.8%), trunk (30.3%), extremities (12.4%), and anogenital region (3.6%). Muscle and bone invasion were documented in 42.7% and 40.3% of cases, respectively. A minority of tumors invaded the orbit (15.0%), dura mater (10.2%), and brain parenchyma (5.1%), whereas 9.5% of patients had lymph node involvement and 10.9% had distant metastases at presentation. The histologic subtype of tumors (highest grade reported) was most commonly invasive/infiltrative (42.8%), followed by nodular (36.9%), morpheic (11.4%), and superficial (8.9%). Ulceration and perineural invasion were present in 61.5% and 8.0% of cases, respectively.

Under the AJCC sixth and seventh edition criteria, stages for patients were, respectively, stage II (55.5% and 59.3%), stage III (32.5% and 14.0%), and stage IV (12.0% and 26.7%). Patient follow-up periods ranged from 0 to180 months (median 20 months). The most commonly performed treatments included surgical excision (74.8%), radiation (21.9%), Mohs surgery (20.9%), and chemotherapy (6.9%). 7.5% of patients received no treatment (or palliative/supportive treatment). In follow-up, 22.9% of patients experienced local recurrence, 8.4% experienced nodal metastases, and 9.8% developed distant metastases. Survival status reported at final follow-ups was as follows: alive without disease (68.6%), alive with disease (11.6%), died of disease (18.4%), and died without disease (1.4%).

Prognostic Factors

The effect of each variable studied on the hazard ratio (HR) for DSD was assessed in univariate (see Table 5, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A46) and multivariate (see Table 6, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A47) analyses. The latter identified independent predictors for DSD in patients with GBCC: age and duration of disease were included in the final model, although they were the only 2 variables included with P-values greater than 0.05 (and less than 0.10). Tumor diameter was a significant independent predictor for DSD [HR: 1.118, P = 0.003], with each 1 cm increase in diameter associated with a 12% increased odds of patients experiencing DSD. Bone invasion was independently predictive of a 4 times greater odds of patients experiencing DSD (HR: 4.187, P = 0.015). Likewise, brain invasion (HR: 8.228, P = 0.001) and distant metastases at presentation (HR: 14.482, P = 0.000) were associated with 8 and 14 times greater odds of DSD in patients, respectively.

Several variables were associated with significantly decreased odds of DSD in multivariate analysis. The presence of multiple common BCCs was associated with 90% decreased odds of DSD (HR: 0.098, P = 0.006). GBCC in the anogenital region also portended a better prognosis, with 96% decreased odds of DSD compared with GBCC involving the head and neck (HR: 0.037, P = 0.015). Finally, orbital invasion also predicted 93% decreased odds of DSD (HR: 0.065, P = 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Pain is uncommon in GBCC (19%) despite significant local tissue destruction. In this review, only a minority of patients had pain with head and neck tumors (18%), muscle invasion (35%), bone invasion (32%), or orbital invasion (12%). The paracrine neuromediators studied were all expressed by BCC. Although expressions of serotonin and β-endorphin were greater in GBCC than in BCC, the difference was not statistically significant. The potential role of these mediators in increasing pain thresholds, altering host behavior,26 and ultimately delaying care in GBCC is suggested by our findings but requires further exploration in prospective studies.

In normal tissues, including skin, met-enkephalin functions as a growth modulator by inhibiting cellular proliferation.32,34,46 Similar functions are implicated for locally produced β-endorphin.22,47 The possibility that endogenous opioids concurrently modulate tissue growth and analgesia is suggested by the contribution of endogenous opioids to injury response and healing in which local analgesic effects occur. Endorphins and enkephalins synthesized by skin20,21,33 can enter circulation or bind locally to opioid receptors on peripheral nerves.22 Paraneoplastic systemic effects represent a potential explanation for lack of pain and neglect in GBCC, although this has yet to be substantiated. The mechanism may be comparable with tanning addiction in which activation of endogenous opioids48,49 or increased levels of serotonin (reviewed in36) are implicated. Another possibility is paracrine anesthesia through activity of opioid peptides on adjacent nerveendings in skin.22,47 Compatible with this idea is the observation that increased POMC expression with increased β-endorphin production occurs in human epidermis after UVR exposure.21,24

Patients with GBCC have unique psychosocial characteristics including a significantly increased likelihood of alcoholism (see Fig. S3, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A36), living alone (see Fig. S4, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A37), and lack of patient concern for their tumors compared with patients with BCC (see Fig S5, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A38). Additionally, GBCCs have specific clinicopathologic characteristics including more aggressive histologic subtypes (invasive/infiltrative/morpheic), adenoid histology, perineural invasion, ulceration, and faster growth rate than BCC (see Figs. S1 and S2, Supplemental Digital Contents, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A34 and http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A35). Adenoid (giant and control) BCC expressed significantly higher levels of β-endorphin and serotonin. Therefore, adenoid phenotype may predict neuromediators production in BCC.

Larger tumor diameter and bone invasion are strong independent predictors for DSD in GBCC (see Table 6, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A47). In this review, patients with a good prognosis tended to have less aggressive tumor histologic subtypes, no muscle or bone invasion, and were frequently treated by excision. Conversely, patients with a poor prognosis tended to have larger tumors, frequently of the head and neck (see Fig. S6, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A39), aggressive histologic subtypes, with muscle and bone invasion (see Fig. S7, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A40). In multivariate analysis, anogenital tumors had a better prognosis than head and neck tumors, likely because of less virulent tumors in non–sun-exposed sites.50 Moreover, multiple (common) BCCs and orbital invasion were surprisingly associated with a lower risk of DSD. These factors require further study to elucidate their role in predicting outcomes in GBCC.

In comparing AJCC sixth and seventh edition staging criteria, the sixth edition was a better outcome predictor for GBCC patients with nonoverlapping survival functions for each stage (see Fig. S8, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/AJDP/A41). This is likely because under the sixth edition criteria, tumors with invasion of deep extradermal structures (ie, muscle, bone) result in T4 (and are graded as at least stage III), and stage IV is strictly defined by distant metastases. Under seventh edition criteria, unless nodal metastases are present, most tumors do not meet the stricter T3 criterion (invasion of maxilla, mandible, orbit, or temporal bone) that would place them in at least stage III.51 As such, fewer tumors qualified for stage III and more tumors fit in stage IV (where the criterion was less strict than the presence of distant metastases). Another explanation is that high-risk features used in the seventh edition criteria (ie, depth of invasion >2 mm, Clark level ≥4, differentiation) were not uniformly reported in the literature.

Limitations in this retrospective study include lack of uniformity in reporting patient characteristics, publication bias, and the relatively small number of published cases. Specifically, multivariate analysis for predictors of DSD in lower-risk strata of patients (ie, those without metastases) could not be performed because of the small number of cases. Prospective trials are necessary to determine a link, if any, between BCC neuromediator production and neglect.

CONCLUSION

GBCC etiopathogenesis is multifactorial. BCC produces neuroactive mediators such as POMC-derived and proenkephalin-derived peptides or serotonin with established roles in altering pain thresholds, mood, and behavior. The role of these neuromediators in the natural history of BCC and neglect deserves further study. Additionally, the clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic factors in patients with GBCC reported here should help clinicians with management decisions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance in data collection: Khalid Afaneh, MD, Jennifer Garbaini, MD, Song Lu, MD, PhD, Ang Lee, MD, Michael Mulvaney, MD, and Luciano Iorrizo, MD for sharing their insights.

Partial support from NIH grants 5R21AR066505-03 and 5R01AR056666-06 provided to Dr Andrzej Slominiski. No additional funding support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This article was presented in part at the 16th Joint Meeting of the International Society of Dermatopathology, February 27 and 28, 2013, Miami, FL and 100th Annual Meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, February 26 to March 4, 2011, San Antonio, TX.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.amjdermatopathology.com).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Albany

References

- 1.American Cancer Society home page. 2013 Available from: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/skincancer-basalandsquamouscell/detailedguide/skin-cancer-basal-and-squamous-cell-key-statistics. Accessed January 10, 2015.

- 2.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283–287. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flohil SC, Seubring I, van Rossum MM, et al. Trends in Basal cell carcinoma incidence rates: a 37-year dutch observational study. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:913–918. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller SJ. Biology of basal cell carcinoma (Part I) J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70001-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gulleth Y, Goldberg N, Silverman RP, et al. What is the best surgical margin for a Basal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1222–1231. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea450d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vico P, Fourez T, Nemec E, et al. Aggressive basal cell carcinoma of head and neck areas. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1995;21:490–497. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(95)96861-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walling HW, Fosko SW, Geraminejad PA, et al. Aggressive basal cell carcinoma: presentation, pathogenesis, and management. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:389–402. doi: 10.1023/B:CANC.0000031775.04618.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beahrs OH, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, et al. Manual for Staging of Cancer. 3rd. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo JS, Snow SN, Reizner GT, et al. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: report of twelve cases with a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:715–719. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70108-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Archontaki M, Stavrianos SD, Korkolis DP, et al. Giant Basal cell carcinoma: clinicopathological analysis of 51 cases and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2655–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ono T, Kitoh M, Kuriya N. Characterization of basal cell epithelioma in the Japanese. J Dermatol. 1982;9:291–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1982.tb02637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betti R, Inselvini E, Moneghini L, et al. Giant basal cell carcinomas: report of four cases and considerations. J Dermatol. 1997;24:317–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1997.tb02797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoccali G, Pajand R, Papa P, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma of the skin: literature review and personal experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:942–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson JK, Altman JS, Rademaker AW. Socioeconomic status and attitudes of 51 patients with giant basal and squamous cell carcinoma and paired controls. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:428–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grange F, Barbe C, Aubin F, et al. Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics associated with thick melanomas: a population-based, case-case study in France. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1370–1376. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lackey PL, Sargent LA, Wong L, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma surgical management and reconstructive challenges. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58:250–254. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000250842.96272.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kokavec R, Fedeles J. Giant basal cell carcinomas: a result of neglect? Acta Chir Plast. 2004;46:67–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubin AI, Chen EH, Ratner D. Basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2262–2269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra044151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slominski A, Wortsman J. Neuroendocrinology of the skin. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:457–487. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.5.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slominski A, Wortsman J, Luger T, et al. Corticotropin releasing hormone and proopiomelanocortin involvement in the cutaneous response to stress. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:979–1020. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slominski AT, Zmijewski MA, Skobowiat C, et al. Sensing the environment: regulation of local and global homeostasis by the Skin’s neuroendocrine system. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2012;212:1–115. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-19683-6_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slominski AT, Zmijewski MA, Zbytek B, et al. Key role of CRF in the skin stress response system. Endocr Rev. 2013;34:827–884. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skobowiat C, Dowdy JC, Sayre RM, et al. Cutaneous hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis homologue—regulation by ultraviolet radiation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E484–E493. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00217.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skobowiat C, Slominski AT. Uvb activates hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in C57BL/6 mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1638–1648. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fell GL, Robinson KC, Mao J, et al. Skin beta-endorphin mediates addiction to UV light. Cell. 2014;157:1527–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim MH, Cho D, Kim HJ, et al. Investigation of the corticotropin-releasing hormone-proopiomelanocortin axis in various skin tumours. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:910–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slominski A, Wortsman J, Mazurkiewicz JE, et al. Detection of proopiomelanocortin-derived antigens in normal and pathologic human skin. J Lab Clin Med. 1993;122:658–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slominski A. Identification of beta-endorphin, alpha-MSH and ACTH peptides in cultured human melanocytes, melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma cells by RP-HPLC. Exp Dermatol. 1998;7:213–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1998.tb00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slominski A, Heasley D, Mazurkiewicz JE, et al. Expression of proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-derived melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) peptides in skin of basal cell carcinoma patients. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:208–215. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLaughlin PJ, Stucki JK, Zagon IS. Modulation of the opioid growth factor ([Met(5)]-enkephalin)-opioid growth factor receptor axis: novel therapies for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2012;34:513–519. doi: 10.1002/hed.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neumann C, Bigliardi-Qi M, Widmann C, et al. The delta-opioid receptor affects epidermal homeostasis via ERK-dependent inhibition of transcription factor POU2F3. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:471–480. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slominski AT, Zmijewski MA, Zbytek B, et al. Regulated proenkephalin expression in human skin and cultured skin cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:613–622. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slominski AT. On the role of the endogenous opioid system in regulating epidermal homeostasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:333–334. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slominski A, Pisarchik A, Semak I, et al. Serotoninergic and melatoninergic systems are fully expressed in human skin. FASEB J. 2002;16:896–898. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0952fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slominski A, Wortsman J, Tobin DJ. The cutaneous serotoninergic/melatoninergic system: securing a place under the sun. FASEB J. 2005;19:176–194. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2079rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slominski A, Pisarchik A, Johansson O, et al. Tryptophan hydroxylase expression in human skin cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1639:80–86. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(03)00124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young S. How to increase serotonin in the human brain without drugs. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:394–399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nordlind K, Azmitia EC, Slominski A. The skin as a mirror of the soul: exploring the possible roles of serotonin. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:301–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slominski A, Pisarchik A, Zbytek B, et al. Functional activity of serotoninergic and melatoninergic systems expressed in the skin. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:144–153. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant JE, Potenza MN, Weinstein A, et al. Introduction to behavioral addictions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:233–241. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.491884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fineberg NA, Potenza MN, Chamberlain SR, et al. Probing compulsive and impulsive behaviors, from animal models to endophenotypes: a narrative review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:591–604. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Potenza MN. The neurobiology of pathological gambling and drug addiction: an overview and new findings. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3181–3189. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gore SM, Kasper M, Williams T, et al. Neuronal differentiation in basal cell carcinoma: possible relationship to Hedgehog pathway activation? J Pathol. 2009;219:61–68. doi: 10.1002/path.2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panuncio A, Vignale R, Lopez G. Immunohistochemical study of nerve fibres in basal cell carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:250–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. The opioid growth factor-opioid growth factor receptor axis: homeostatic regulator of cell proliferation and its implications for health and disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:746–755. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bigliardi PL, Tobin DJ, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, et al. Opioids and the skin– where do we stand? Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:424–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nolan BV, Feldman SR. Ultraviolet tanning addiction. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:109–112. v. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harrington CR, Beswick TC, Leitenberger J, et al. Addictive-like behaviours to ultraviolet light among frequent indoor tanners. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:33–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crowson AN, Magro CM, Kadin ME, et al. Differential expression of the bcl-2 oncogene in human basal cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:355–359. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th. New York, NY: NYL Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.