Abstract

Background

The development of behavioral addictions (BAs) in association with dopamine agonists (DAs, commonly used to treat Parkinson’s disease) has been reported. A recent report presented data that these associations are evident in the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), a database containing information on adverse drug event and medication error reports submitted to the FDA. However, given that vulnerability to publicity-stimulated reporting is a potential limitation of spontaneous reporting systems like the FAERS, the potential impact of publicity on reporting in this case remains unclear.

Method and aims

To investigate the potential impact of publicity on FAERS reporting of BAs in association with DAs (BAs w/DAs) as presented by Moore, Glenmullen, and Mattison (2014), news stories covering a BA/DA association were identified and compared with BA w/DA and other reporting data in the FAERS.

Results

Fluctuations in the growth of BA w/DA reporting to the FAERS between 2003 and 2012 appear to coincide with multiple periods of intensive media coverage of a BA/DA association, a pattern that is not evident in other reporting data in the FAERS.

Discussion/Conclusions

Publicity may stimulate reporting of adverse events and premature dismissal of the potential influence of publicity on reporting may lead to mistaking an increased risk of an adverse event being reported for an increased risk of an adverse event occurring.

Keywords: behavioral addictions, impulse control disorders, Parkinson’s disease, dopamine agonists, gambling, FDA Adverse Event Reporting System

Introduction

The development of behavioral addictions (BAs, also referred to as impulse control disorders) in association with dopamine agonists (DAs, commonly used to treat Parkinson’s disease) has been reported (Dodd et al., 2005; Driver-Dunckley, Samanta, & Stacy, 2003; Szarfman, Doraiswamy, Tonning, & Levine, 2006; Weintraub et al., 2010). Moore et al. (2014) present evidence that these reported associations are evident in the US Food & Drug Administration’s (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), a database containing information on adverse drug event (ADE) and medication error reports submitted to the FDA. Specifically, Moore et al. (2014) conducted a retrospective disproportionality analysis based on the 2.7 million serious domestic and foreign ADEs reported to the FAERS from 2003 to 2012. A threshold consisting of a proportional reporting ratio (PRR) ≥ 2 was used to detect signals (drug-associated adverse events) involving any of six DAs and any of 10 terms (or ADEs) in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities characterized as BAs. They identified 1,580 reports containing at least one BA, 710 of which also contained a DA, and reported a PRR for reports containing both a BA and a DA (BAs w/DAs) of 277.6 (p < 0.001).

The authors concluded that their findings confirm prior reports of a BA/DA association. However, given three factors, it is possible that their findings could have been affected by publicity. First, vulnerability to publicity-stimulated reporting has been described as a limitation of spontaneous reporting systems like the FAERS (Bate & Evans, 2009; Moore et al., 2003). Second, between 2003 and 2012, the development of BAs in association with DAs received considerable media coverage on multiple occasions. Third, a 2014 research report, which, in its analysis of FAERS reporting cast a wider net than Moore et al. (2014) with respect to both number of BAs analyzed (16 versus 10) and type of report analyzed (both serious and non-serious reports were included), found no or only very weak associations prior to publicity between DAs and BAs that could be grouped under the general headings binge eating, compulsive shopping, and hypersexuality (pre-publicity data on reports of gambling to the FAERS are not freely available) (Gendreau & Potenza, 2014).

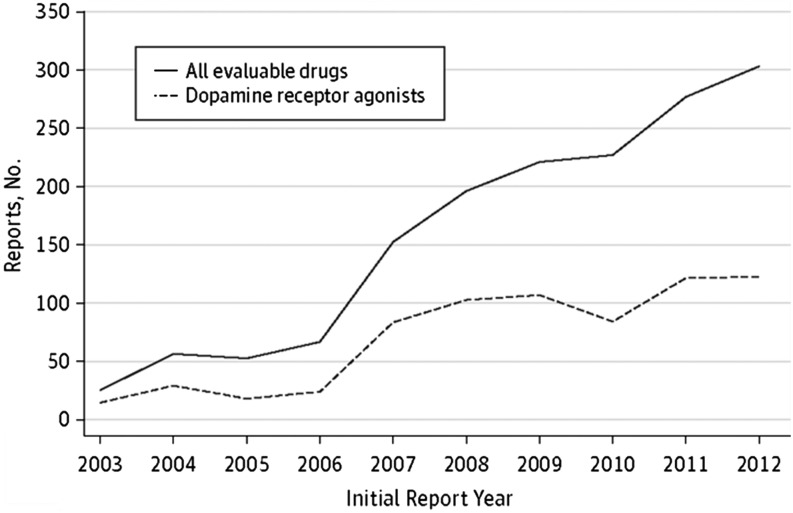

Moore et al. (2014) briefly allude to the issue of publicity in their discussion and suggest that it cannot account for their findings. Specifically, they characterize growth in BA w/DA reporting (“dopamine receptor agonists” in Figure 1) between 2003 and 2012 as steady and conclude that it is therefore unlikely that a burst of publicity or specific events explain their findings. We contend that growth in BA w/DA reporting between 2003 and 2012 was not steady, but rather it fluctuated, with upticks in reporting in 2004 (approximately 133%) and 2011 (approximately 49%), and a sustained period of growth between 2005 and 2009 (approximately 588%). Given the observations listed in the previous paragraph, we hypothesized that these fluctuations may coincide with publicity.

Figure 1.

Trend over time for reports of pathological gambling, hypersexuality, and related impulse control disorders.

Total domestic and foreign reports of serious injury received by the US Food and Drug Administration containing any of 10 terms in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities that characterize the impulse control disorder under study. (Reproduced with permission from the American Medical Association: JAMA Internal Medicine (Moore et al. (2014); 174(12):1930–1933.) Copyright © 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.)

Note: In the current study, impulse control disorders are referred to as behavioral addictions, or BAs

Methods

To investigate the possibility that these fluctuations may coincide with media coverage, we conducted Internet searches of 16 major US and international English-language media outlets between 2003 and 2012 for the keywords Parkinson’s AND gambling. Of the 68 news stories identified using this strategy, 35 were included. News stories were excluded if they only briefly mentioned a BA/DA association (26 stories); keywords were found among “comments” on a story (four stories); they were in “question and answer” or “Dear Doctor” format (two stories); or the webpage or article was no longer accessible (one story).

Ethics

Both authors have conformed to the highest standards of ethical conduct in the submission of accurate data, acknowledging the work of others and divulging potential conflicts of interest. As the study involved the use of publicly accessible, de-identified data, signed informed consent was not necessary for this study. Given the use of publicly accessible, de-identified data, the study is exempted from IRB review under code of federal regulations 45 CFR 46.101(b).

Results

Of the 35 included news stories, 15 were precipitated by scientific publications (43%); 10 by lawsuits (29%); 7 by conference presentations (20%); 1 by a change in pharmaceutical company advertising (3%); 1 by a patient’s story (3%); and 1 for which the catalyst was unclear (3%).

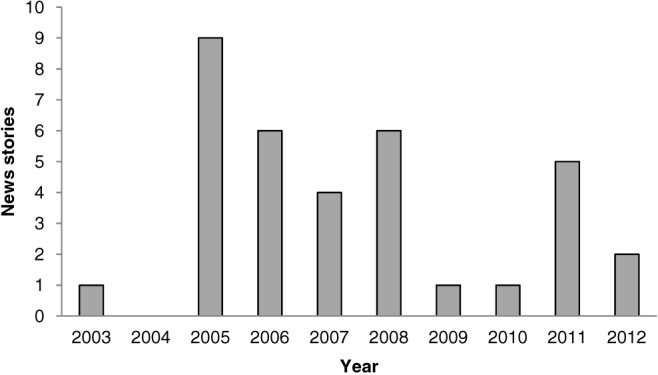

Results are summarized in Figure 2. The uptick in BA w/DA reporting in 2004 seen in Figure 1 follows a news story in the New York Times in August 2003 (O’Neil, 2003), precipitated by the publication in the same month of research conducted by Driver-Dunckley et al. (2003). The uptick in 2011 follows four news stories in January and February of 2011 triggered by lawsuits, as well as a CBS news story in June 2010 (Edwards, 2010) precipitated by a scientific publication (Weintraub et al., 2010). The approximately 588% growth in BA w/DA reporting observed between 2005 and 2009 coincides with the publication of 26 news stories (74% of the 35 news stories included) between July 2005 and April 2009, most of which were prompted by scientific publications (Bostwick, Hecksel, Stevens, Bower, & Ahlskog, 2009; Dodd et al., 2005; Szarfman et al., 2006; Voon et al., 2007), conference presentations, and lawsuits.

Figure 2.

Number of news stories covering a BA/DA association, 2003–2012.

BA = behavioral addiction, DA = dopamine agonist.

Note: News stories data were compiled from Internet searches of 16 major US and international English-language media outlets for the terms Parkinson’s AND gambling (ABC News, CBS News, CNBC, CNN, The Globe & Mail, The Guardian, Huffington Post, MSNBC, NBC News, The New York Times, NPR, Scientific American, Time, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post)

Discussion

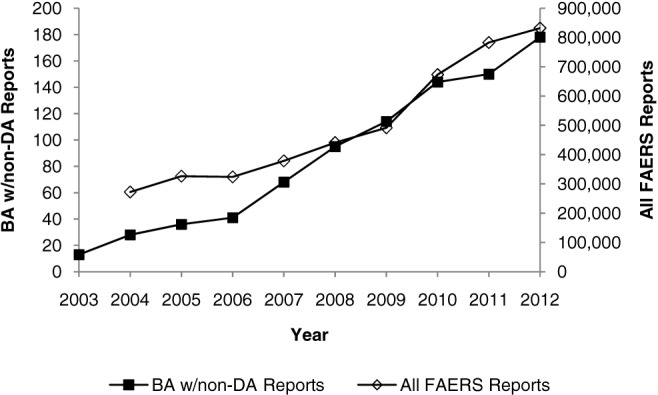

Upticks in BA w/DA reporting to the FAERS appear to either follow or coincide with publication of news stories. Moreover, fluctuations in BA w/DA reporting are not reflected in the trajectories plotted for all FAERS reports or BA w/non-DA reports (Figure 3), which suggests the presence of some influence on the BA w/DA reporting rate specifically. That fluctuations in news coverage may coincide with fluctuations in BA w/DA reporting suggests the possibility that publicity may have influenced reporting.

Figure 3.

Trend over time for BA w/non-DA and all FAERS reports, 2003–2012.

FAERS = US Food & Drug Administration’s (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System, BA = behavioral addiction, DA = dopamine agonist.

Note: BA w/non-DA reports data were estimated based on data presented in Moore et al. (2014) (see Figure 1). All FAERS reports data were obtained from the FDA’s website at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm083765.htm

Given the possibility that publicity could have influenced their findings, it would have been helpful if Moore et al. (2014) had provided PRRs for clinically related groupings of the 10 BAs analyzed. This would make it easier to assess the degree to which the overall PRR of 277.6 may be driven by pathological gambling/gambling (two separate ADEs in the FAERS), which, in 2003, was the first BA to be reported in association with DAs in the mainstream media. Pathological gambling/gambling was also the BA most frequently reported to the FAERS between 2003 and 2012, accounting for 42.7% of the 1,902 reports of BAs identified by (Moore et al., 2014). It would also have been interesting to see a comparison between the 2003 PRRs (pre-publicity for all but pathological gambling) and the 2012 PRRs (post-publicity for all BAs) for clinically related groupings of the 10 BAs analyzed.

It should be noted that significant complexities exist in identifying the specific factors that might cause ADEs and their reporting. While publicity may influence reporting, it is also possible that FAERS reporting may have led to increased publicity, perhaps indirectly through analysis and reporting of findings. Possible examples may include through the FDA’s quarterly reporting of potential drug safety issues identified via analysis of FAERS data; updates to product labeling or product advertising resulting from analysis of FAERS reporting; or scientific publication of analysis of FAERS reporting. Of the 35 news stories included in the analysis, one cites as its catalyst an update to possible adverse events listed in a product’s television advertisements, a change the product manufacturer says was prompted by a request from the FDA, and two stories cite as an impetus scientific publication of analysis of FAERS reporting. We also note the gradual nature of the sizable uptick in BA w/DA reporting between 2005 and 2009, which occurs in the midst of several years of increased media coverage of a BA/DA association. This finding would be consistent with a possible lag, with information taking time to circulate and lead to reporting, although other possibilities also exist. It is possible that the BA w/DA data presented in Figure 1 are influenced by multiple factors, some of which are indicated above. While we do not cover an exhaustive list, the notion that reporting of BAs in association with DAs might be influenced by publicity has important clinical and public health implications, and is thus not a notion that should be prematurely dismissed.

Conclusions

In summary, a BA/DA association has received considerable publicity since it was first reported in 2003. Data suggest that publicity may stimulate ADE reporting, and in this case it may coincide with fluctuations in BA w/DA reporting. It is important to evaluate the potential effect of publicity on ADE reporting to guard against mistaking an increased risk of an ADE being reported for an increased risk of an ADE occurring (Moore et al., 2003).

Authors’ contributions

KG: contributed study concept and design, collected, analyzed and interpreted data, and performed initial drafting of the manuscript. MP: obtained funding and aided in analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript review and editing. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the research endeavor in order to qualify for authorship, and take public responsibility for its content. The corresponding author has had access to all data from the study and both authors have had complete freedom to direct its analysis, interpretation and reporting without influence from funding agencies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Ms. Gendreau has no financial relationships to disclose. Dr. Potenza has received financial support or compensation for the following: Dr. Potenza has consulted for and advised Lundbeck, Ironwood, INSYS, Shire and RiverMend Health for issues relating to impulse control disorders, gambling disorder, eating disorders, substance addictions and gender-related differences; has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, Veteran’s Administration, Mohegan Sun Casino, the National Center for Responsible Gaming, and Pfizer pharmaceuticals; has participated in surveys, mailings or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse control disorders or other health topics; has consulted for gambling and legal entities on issues related to addictions or impulse control disorders; has provided clinical care in the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Problem Gambling Services Program; has performed grant reviews for the National Institutes of Health and other agencies; has guest-edited journal sections; has given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events and other clinical or scientific venues; and has generated books or book chapters for publishers of mental health texts.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: Supported by a Center of Excellence Grant from the National Center for Responsible Gaming, an unrestricted research gift from Mohegan Sun Casino, the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, and the Connecticut Mental Health Center. The content of the manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies, and these agencies did not contribute to the content of this manuscript.

References

- Bate A., Evans S. J. W. (2009). Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 18(6), 427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick J. M., Hecksel K. A., Stevens S. R., Bower J. H., Ahlskog J. E. (2009). Frequency of new-onset pathologic compulsive gambling or hypersexuality after drug treatment of idiopathic Parkinson disease. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 84(4), 310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd M. L., Klos K. J., Bower J. H., Geda Y. E., Josephs K. A., Ahlskog J. E. (2005). Pathological gambling caused by drugs used to treat Parkinson disease. Archives of Neurology, 62(9), 1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver-Dunckley E., Samanta J., Stacy M. (2003). Pathological gambling associated with dopamine agonist therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology, 61(3), 422–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. (June 7, 2010). Sex, shopping addiction lawsuits may force faster drug-safety updates. CBS News. Retrieved from http://www.cbsnews.com/news/sex-shopping-addiction-lawsuits-may-force-faster-drug-safety-updates/

- Gendreau K. E., Potenza M. N. (2014). Detecting associations between behavioral addictions and dopamine agonists in the Food & Drug Administration’s Adverse Event database. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(1), 21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore N., Hall G., Sturkenboom M., Mann R., Lagnaoui R., Begaud B. (2003). Biases affecting the proportional reporting ratio (PRR) in spontaneous reports pharmacovigilance databases: The example of sertindole. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 12(4), 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore T. J., Glenmullen J., Mattison D. R. (2014). Reports of pathological gambling, hypersexuality, and compulsive shopping associated with dopamine receptor agonist drugs. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(12), 1930–1933. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil J. (August 12, 2003). Gambling and Parkinson’s drug. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2003/08/12/health/vital-signs-risks-and-remedies-gambling-and-parkinson-s-drug.html

- Szarfman A., Doraiswamy P. M., Tonning J. M., Levine J. G. (2006). Association between pathologic gambling and parkinsonian therapy as detected in the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event database. Archives of Neurology, 63(2), 299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon V., Thomsen T., Miyasaki J. M., de Souza M., Shafro A., Fox S. H., Duff-Canning S., Lang A. E., Zurowski M. (2007). Factors associated with dopaminergic drug-related pathological gambling in Parkinson disease. Archives of Neurology, 64(2), 212–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub D., Koester J., Potenza M. N., Siderowf A. D., Stacy M., Voon V., Whetteckey J., Wunderlich G. R., Lang A. E. (2010). Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: A cross-sectional study of 3090 patients. Archives of Neurology, 67(5), 589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]