Abstract

Background and aims

The current study examined the mediating role of maladaptive perfectionism among parental psychological control, eating disorder symptoms, and exercise dependence symptoms by gender in habitual exercisers.

Methods

Participants were 348 Italian exercisers (n = 178 men and n = 170 women; M age = 20.57, SD = 1.13) who completed self-report questionnaires assessing their parental psychological control, maladaptive perfectionism, eating disorder symptoms, and exercise dependence symptoms.

Results

Results of the present study confirmed the mediating role of maladaptive perfectionism for eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms for the male and female exercisers in the maternal data. In the paternal data, maladaptive perfectionism mediated the relationships between paternal psychological control and eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms as full mediator for female participants and as partial mediator for male participants.

Discussion

Findings of the present study suggest that it may be beneficial to consider dimensions of maladaptive perfectionism and parental psychological control when studying eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms in habitual exerciser.

Keywords: psychological control, maladaptive perfectionism, eating disorder, exercise dependence, habitual exerciser

Exercise dependence is a term used to quantify and describe pathological behaviors and attitudes related to exercise that are characterized by a preoccupation with exercise routines, withdrawal symptoms when unable to exercise, and an interference with social relationships and occupational commitments (Berczik et al., 2012; Schreiber & Hausenblas, 2015). In short, exercise dependence is a maladaptive pattern of moderate to vigorous excessive exercise that manifests in negative physiological, psychological, and cognitive symptoms (Hausenblas & Symons Downs, 2002a).

Based on the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-IV-R (DSM-IV-R) criteria for substance dependence (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), Hausenblas and Symons Downs (2002a) identified the following seven criteria or symptoms, at least three of which must be met for the diagnosis of exercise dependence. First, tolerance is the need for increasing the duration, frequency, and intensity of exercise to obtain the desired effect or by experiencing less effect with the extended use of the same amount of the exercise. Withdrawal is characterized by experiencing unpleasant symptoms (such as anxiety, depression, and fatigue) when exercise stops or by using exercise as a way to relieve or prevent these withdrawal symptoms. Intention effects occur when exercise behavior is greater than what was originally intended. Loss of control is the inability to reduce exercise, despite the desire to do so. Time refers to a relatively large amount of time spent in exercise (e.g., vacations are exercise-related) or exercise-related activities. Reductions in other activities are manifested by the reduction of social, occupational, or recreational activities because of physical activity (e.g., exercising rather than spending time with family and friends). Continuity is a persistence of exercise despite recurring negative physical or psychological effects (e.g., continued exercising despite an overuse injury).

There is a strong link between exercise dependence and eating disorders, with eating disorders being the most common disorder to co-occur with exercise dependence (Freimuth, Moniz, & Kim, 2011). Freimuth et al. (2011) noted that about 39–48% of people suffering from an eating disorder also are exercise dependent (Bamber, Cockerill, Rodgers, & Carroll, 2003; Klein et al., 2004). Because of the negative physical, psychological, and social outcomes and high co-occurrence of both exercise dependence and eating disorders it is important to examine variables that predict symptoms of both of these disorders (Adams, 2009; Costa & Oliva, 2012; Gardner, Stark, Friedman, & Jackson, 2000). Knowledge of these specific characteristics will aid in the development and implementation of prevention and treatment interventions.

As well, given the strong relationship between exercise dependence and eating disorders, certain etiological factors may be common among these pathologies. In particular, researchers have demonstrated the role of perfectionism and parental control in the etiology and course of eating disorders (Polivy & Herman, 2002; Soenens et al., 2008). However, there is no indication as to whether the interaction between parental psychological control and maladaptive perfectionism would typify those identified as being exercise dependent.

Parental psychological control is an intrusive parenting tactics to control the child's emotional state and to make children act, fell and think in parentally approved ways. Such intrusive tactics include love withdrawal, guilt-induction, conditional approval, shaming, instilling anxiety, and thinking patterns (Barber, 1996). Parental psychological control represents a risk factor for maladjustment during different life period, including adolescence and emerging adults (Barber, Stolz, & Olsen, 2005; Costa, Hausenblas, Oliva, Cuzzocrea, & Larcan, 2015; Costa, Soenens, Gugliandolo, Cuzzocrea, & Larcan, 2015; Gugliandolo, Costa, Cuzzocrea, & Larcan, 2014; Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2010; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, Luyten, Duriez, & Goossens, 2005).

Parental psychological control may have a relevant role in the sport context and it may be related to unhealthy behaviors (Barber & Harmon, 2002; Costa, Hausenblas, et al., 2015; Miller, 2012; Soenens et al., 2008; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, & Luyten, 2010). Perceived parental psychological control, in fact, is related to both eating disorders and exercise dependence (Costa, Hausenblas, et al., 2015). That is, parental psychological control is characterized by contingent expression of love, based on the performance of children, creating negative self-evaluations with the consequence of inducing rigid eating behaviors and excessive exercise (Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2010; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, et al., 2005). For this reason, maladaptive perfectionism could have a relevant role in the relation between parental psychological control and exercise dependence and eating disorders. Soenens et al. (2008) demonstrated that maladaptive perfectionism mediated the links between psychological control and eating disorder symptoms. Eating disorders share numerous aspects with exercise dependence symptoms and it is plausible that they have a similar etiological process. Although the model suggested by Soenens et al. (2008) was not verified in an exercise context, it is reasonable that perfectionism could have a role as an intervening variable also in relationship to parental psychological control and exercise dependence symptoms. Integrating efforts to understand common etiology of exercise dependence and eating disorders could have the economic efficiency of addressing two conditions within a single prevention intervention and also increase our understanding of the onset and maintenance of problematic behaviors in an exercise context. Furthermore, despite that exercise dependence is related to parental psychological control (Costa, Hausenblas, et al., 2015) and perfectionism (Costa, Coppolino, & Oliva, 2015; Hall, Hill, Appleton, & Kozub, 2009; Symons Downs, Hausenblas, & Nigg, 2004), the role of both etiological factors (parental psychological control and perfectionism) has not been investigated together with exercise dependence. Understanding the role of perfectionism, may help identify those most at-risk for exercise dependence and how parental psychological control may exacerbates exercise dependence symptoms.

Perfectionism, in fact, is a multidimensional construct comprising both maladaptive and adaptive features (Dunkley, Blankstein, Masheb, & Grilo, 2006). A central feature of perfectionism is the setting of high achievement standards, which in itself, is not pathological. However, previous studies have shown that perfectionists with high personal standards tend to have strong negative self-evaluation to their unsatisfactory performance, that could create a rigid adherence to unrealistic standards (Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, 1990; Shafran & Mansell, 2001; Soenens et al., 2008). Previous studies suggest a central role for maladaptive perfectionism with the etiology and course of eating disorders and exercise dependence (Hall et al., 2009; Shafran & Mansell, 2001). In according with Soenens et al. (2008), driven by their sense of incompetence and lack of control, maladaptive perfectionists could develop a rigid focus on eating and exercise, and would engage in an escalating pattern of disordered eating and exercise dependence behaviors (Flett, Hewitt, Blankstein, & Mosher, 1995; Hall, Kerr, Kozub, & Finnie, 2007; Shafran, Cooper, & Fairburn, 2002).

In summary, research examining perfectionism as an intervening variable in associations between perceived parental control and eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms is needed for several reasons. First, perfectionism is an important risk factor that possibly interacts with other risk factors to predict eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms (Boone, Soenens, Braet, & Goossens, 2010; Hall et al., 2009). Second, several studies propose that controlling parenting may promote perfectionist concerns (Enns, Cox, & Larsen, 2000; Flett, Madorsky, Hewitt, & Heisel, 2002; Soenens et al., 2008). In according with Soenens et al. (2008) psychologically controlling parents would emphasize the attitude of their children to criticize themselves with feelings of guilt when failing to meet their standards, creating also the idea in their children that failure is unacceptable and that love of parents depends on the respect of the rules, risking the development of a maladaptive perfectionism orientation (Flett et al., 2002; Frost et al., 1990). Fourth, a maladaptive perfectionist orientation would, in turn, create a vulnerability to disordered eating behaviors (Soenens et al., 2008) and excessive exercise and mediate the relations between psychologically controlling parenting and eating disorder and exercise dependence. Finally, identification of appropriate risk factors, integrating environmental (i.e., parental psychological control) and individual (i.e., maladaptive perfectionism) variables, for the condition being targeted is essential to developing effective prevention interventions (Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord, & Kupfer, 2001).

Gender is a very important factor in both eating pathology and exercise dependence. Women are more likely to develop eating disorders than men, while women are less likely to be exercise dependent than men (Costa, Hausenblas, Oliva, Cuzzocrea, & Larcan, 2013; Hoek, 2006). However, some relationships among psychological control, perfectionism, eating disorder and exercise dependence are inconsistent in male and female samples (Costa, Hausenblas, et al., 2013; Miller & Mesagno, 2014; Paulson & Rutledge, 2014; Soenens et al., 2008). For this reason, the present study aims to explore the relationship among exercise dependence, eating disorder, maladaptive perfectionism, and parental psychological control symptoms by gender. Consistent with previous research, it was hypothesized that higher parental psychological control will predict increased exercise dependence and eating disorder symptoms (Costa, Hausenblas, et al., 2015; Soenens et al., 2008). It was also hypothesized that higher parental psychological control will predict increased use of maladaptive perfectionism and the use of maladaptive perfectionism should then predict increased exercise dependence and eating disorder symptoms. That is, maladaptive perfectionism should mediate the direct relationship among parental psychological control, exercise dependence symptoms, and eating disorder symptoms. Finally, it was hypothesized that, despite mean-level differences on some of the study variables (e.g., women report higher eating disorder symptoms than men), the relationship between the study constructs would be consistent across gender.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 348 Italian habitual exercisers that had been exercising for more than 6 months (n = 178 men and n = 170 women; age range = 19 to 22 years of age; M = 20.57, SD = 1.13; body mass index: M = 22.63, SD = 3.35). The participants were mainly recruited from gyms and sport teams and spent a mean of 7.30 hours per week training (SD = 4.81). Most of the participants (n = 323) had a high school diploma, 16 had a lower secondary education diploma, 8 had a university degree, and 1 participant did not report this information. All the participants came from two-parent families and they still lived with their parents.

Procedure

Our convenient sample was recruited by soliciting volunteers through friends and appeals to gyms and sport associations in Messina and Reggio Calabria. After describing the study’s purpose, the inclusion criteria was presented and participants that met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate then signed the informed consent and voluntarily completed the questionnaires individually or in small groups under the supervision of an experimenter. Inclusion criteria were that exerciser had trained for at least 6 consecutive months, lived at home with both parents, and were at least 18 years of age. Of the 424 participants who met the inclusion criteria, 375 agreed to participate in the study. After signing the informed consent, 27 participants did not complete the questionnaires. The final sample consisted of 348 participants, representing a response rate of 82%. The questionnaires took about 30 minutes to complete.

Measures

Psychological control

The 8-item Italian version of the Psychological Control Scale–Youth Self-Report (PCS-YSR; Barber, 1996) was used to measure perception of psychological control. Barber (1996) provided evidence for the validity and one-dimensional factor structure of this scale. Subjects responded on a 3-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 “not like her (him)” to 3 “a lot like her (him)” with higher scores reflecting greater perception of parental psychological control. Subjects rated psychological control for both parents separately to examine the individual contribution of mothers and fathers. The reliability and validity of PCS-YSR have been demonstrated in cross-cultural research (Barber et al., 2005) and this scale has adequate psychometric properties (Barber, 1996; Barber et al., 2005). The Italian version of this instrument is widely used in research (Filippello, Sorrenti, Buzzai, & Costa, 2015; Gugliandolo et al., 2014).

Maladaptive perfectionism

The Concern over Mistakes Scale (nine items, e.g., “People will probably think less of me if I make a mistake”) and the Doubts about Actions Scale (four items, e.g., “Even when I do something very carefully, I often feel that it is not quite right”) from the Italian version of the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS; Frost et al., 1990) were used to measure maladaptive perfections (Bieling, Israeli, & Antony, 2004; Frost et al., 1990). A maladaptive perfectionism scale was constructed by computing the mean of the items tapping Concern over Mistakes and Doubts about Actions with a five-point response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (Soenens, Elliot, et al., 2005; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, et al., 2005; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, Duriez, & Goossens, 2006). For the Italian version of the MPS (Lombardo, 2008), items on the subscales Concern over Mistakes (CM) and Doubts about Actions (D) loaded into a unique factor, that represent the scales Concern over Mistakes and Doubts about Actions (CMD). This scale has good psychometric characteristics in various countries, including Italy (Lombardo, 2008; Soenens, Elliot, et al., 2005; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, et al., 2005).

Eating disorder symptoms

The Italian version of the Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26; Dotti & Lazzari, 1998; Garner, Olmsted, Bohr, & Garfinkel, 1982) was used. The EAT-26 is a 26-item, self-report questionnaire that measures the level of disordered eating attitudes, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, using a six point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (always). The questionnaire includes three subscales: Dieting, Bulimia and Food Preoccupation, and Oral Control. Scores greater than 20 indicate abnormal eating behaviors (Garner, Olmsted, & Polivy, 1983). The psychometric properties of the EAT are good and was widely used in research (Doninger, Enders, & Burnett, 2005; Koenig & Wasserman, 1995; Zmijewski & Howard, 2003).

Exercise dependence symptoms

The Italian version of the Exercise Dependence Scale−R (EDS-R; Costa, Cuzzocrea, Hausenblas, Larcan, & Oliva, 2012; Symons Downs et al., 2004) was used to measure exercise dependence symptoms. The EDS-R consists of 21 items scored on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always). Higher scores indicate more exercise dependence symptoms. The instrument has seven subscales (three items for each) based on the DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance dependence and a total score. The subscales are: (a) Withdrawal (e.g., “I exercise to avoid feeling anxious”); (b) Continuance (e.g., “I exercise despite recurring physical problems”); (c) Tolerance (e.g., “I continually increase my exercise intensity to achieve the desired effect/benefits”); (d) Lack of control (e.g., “I am unable to reduce how long I exercise”); (e) Reduction in other activities (e.g., “I would rather exercise than spend time with family/friends”); (f) Time (e.g., “I spend most of my free time exercising”); and (g) Intention effects (e.g., “I exercise longer than I intend”). The criteria established in the DSM-IV-TR was utilised to classify individuals in the following exercise dependence groups: at-risk for exercise dependence (i.e., scores of 5–6 on average on the Likert scale in at least three of the seven criteria), non-dependent symptomatic (i.e., scores of 3–4 on average in at least three criteria, or scores of 5–6 on average combined with scores of 3–4 on average in three criteria, but failing to meet the criteria of at-risk conditions), and nondependent asymptomatic (i.e., scores of 1–2 on average in at least three criteria). The psychometric properties of the of the Italian EDS-R are excellent (Costa et al., 2012; Costa & Oliva, 2012; Oliva, Costa, & Larcan, 2013).

Data analysis

Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) with latent variables was utilized to examine whether maladaptive perfectionism could account for (i.e., mediate) the relationship between parental psychological control, eating disorder symptoms, and exercise dependence symptoms by gender. The models included latent variables for maladaptive perfectionism, parental psychological control, eating disorder symptoms, and exercise dependence symptoms. Both paternal and maternal psychological control and maladaptive perfectionism comprised three parcels. Instead of using separate items as indicators, three parcels (groups) of items was aggregate and used as indicators of the latent constructs. Several studies have shown that parcelling has some advantages relative to the use of individual items. Individual parcels are likely to have a stronger relation to the latent factor and are less likely to be influenced by method effects, furthermore parcelling results in a smaller number of indicators per latent factor and is more likely to meet the assumptions of normality (Coffman & MacCallum, 2005; Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002; Marsh, Hau, Balla, & Grayson, 1998). Analysis of the covariance matrices was conducted using EQS 6.2 and solutions were generated on the basis of maximum-likelihood estimation.

To explore the mediating role of need satisfaction, the SEM approach advanced by Baron and Kenny (1986), Holmbeck (1997), and Shrout and Bolger (2002) for testing mediation was used. Additionally, bootstrapping was used to estimate the standard errors (SEs) and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) for all model estimates (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Hu and Bentler (1999) argued for using combinations of cut-off values to examine model fit. Accordingly, we examined the chi-square statistic, and fit indices such as the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), the Standard Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Hu and Bentler (1999) proposed that values of CFI that are equal or greater than .90, values of NNFI that are equal or greater than .90, values of SRMR lower than .08 and values of RMSEA that are equal or lower than .06 indicate sufficient model fit.

Ethics

Ethical principles were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Messina, Messina, Italy approved the study. All participants were informed about the study and provided informed consent before participating in the study procedures.

Results

Preliminary analysis

Based on the EDS-R and EAT-26 criteria, 11 participants (3%; 5 men and 6 women) were classified as at-risk for both exercise dependence and eating disorder, 11 participants (3%; 8 men and 3 women) were classified as at-risk for exercise dependence only, and 41 participants (12%; 14 men and 27 women) were classified as at-risk only for eating disorder (see Table 1 for descriptive information). Preliminary analyses revealed that the men scored significantly higher than the women on exercise dependence symptoms, t(346) = 2.75, p < .01. The women scored significantly higher than the men on eating disorder attitudes, t(346) = 3.23, p < .01. No significant gender differences were evidenced for maladaptive perfections, psychological control mother, and psychological control father. The five constructs were all positively related (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Mean (M), standard deviation (SD), and Cronbach’s alpha (α) for the male and female samples

| Male | Female | |||||

| α | M | SD | α | M | SD | |

| 1. Psychological control mother | .83 | 1.61 | .47 | .82 | 1.62 | .47 |

| 2. Psychological control father | .80 | 1.52 | .45 | .79 | 1.58 | .46 |

| 3. Maladaptive perfectionism | .93 | 2.59 | .76 | .88 | 2.58 | .66 |

| 4. Eating disorder | .92 | 2.43 | 1.02 | .89 | 2.73** | .97 |

| 5. Exercise dependence | .95 | 11.66** | 13.02 | .94 | 7.67 | 9.89 |

Note: ** value significantly higher between gender for p < .01.

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlational coefficients of the variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1. Psychological control mother | − | .53** | .59** | .27** | .29** |

| 2. Psychological control father | .45** | − | .41** | .24** | .17* |

| 3. Maladaptive perfectionism | .46** | .37** | − | .43** | .42** |

| 4. Eating disorder | .20** | .31** | .36** | − | .52** |

| 5. Exercise dependence | .20** | .29** | .34** | .37** | − |

Note: *p < .05; **p < .01. Lower diagonal correlation matrix of the male data; upper diagonal correlation matrix of the female data.

Mediation analysis for the male participants

First, a predictor model was estimated to test the direct paths from the predictor (i.e., parental psychological control) to the outcome variable (i.e., eating disorder and exercise dependence) in the male sample, including correlations between the error terms for exercise dependence and eating disorder symptoms. This model did not include maladaptive perfectionism, to verify the first step of the mediation process, in which an acceptable fit of a model comprising only direct paths between the predictor variables and the outcome is confirmed. Estimation of the maternal model, χ2(62) = 127.60, p < .001; CFI = .93; NNFI = .92; SRMR = .06; RMSEA = .08 (90% CI = .06–.10), showed a significant path from psychological control to eating disorder (β = .23; p < .01), and exercise dependence (β = .25; p < .01). Similarly, estimation of the paternal model, χ2(62) = 124.76, p < .01; CFI = .93; NNFI = .92; SRMR = .06, RMSEA = .08 (90% CI = .06–.10), showed a significant path from psychological control to eating disorder (β = .36; p < .01), and exercise dependence (β = .37; p < .01).

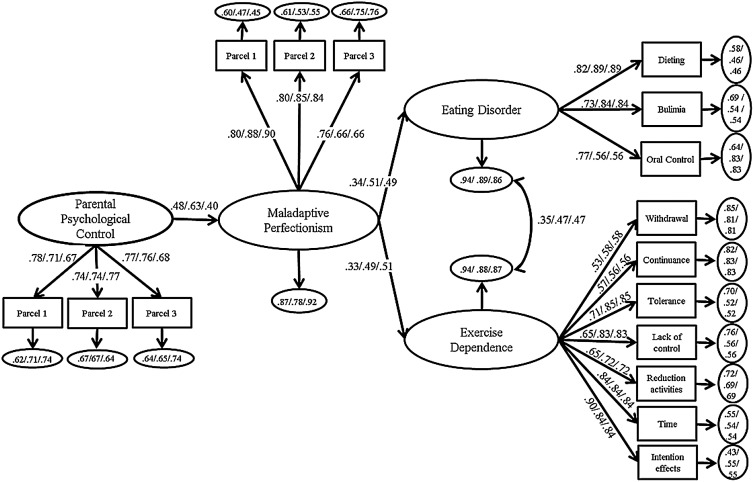

Second, a full mediation model with psychological control was tested, that is, a model in which psychological control was related only indirectly to eating disorder and exercise dependence through maladaptive perfectionism, including correlations between the error terms for exercise dependence and eating disorder symptoms. Estimation of this model (see Figure 1) yielded acceptable fit for both the maternal data, χ2(100) = 168.49, p < .01; CFI = .94; NNFI = .93; SRMR = .06, RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .05–.08), and the paternal data, χ2(100) = 176.89, p < .01; CFI =.93; NNFI = .92; SRMR = .09, RMSEA = .07 (90% CI = .05–.08). Psychological control was related positively to maladaptive perfectionism in both the maternal (β = .49; p < .01) and paternal model (β = .42; p < .01). In turn, maladaptive perfectionism was related positively to eating disorders (β = .34; p < .01), and exercise dependence (β = .33; p < .01) in the maternal model. Maladaptive perfectionism was also related positively to eating disorders (β = .35; p < .01), and exercise dependence (β = .35; p < .01) in the paternal model.

Figure 1.

Full mediation models between psychological control, maladaptive perfectionism, eating disorder and exercise dependence. Note: Coefficients shown are standardized path coefficients. The first coefficient shown is for the maternal psychological control model in a male sample. The second coefficient shown is for the maternal psychological control model in a female sample. The third coefficient shown is for the paternal psychological control model in a female sample

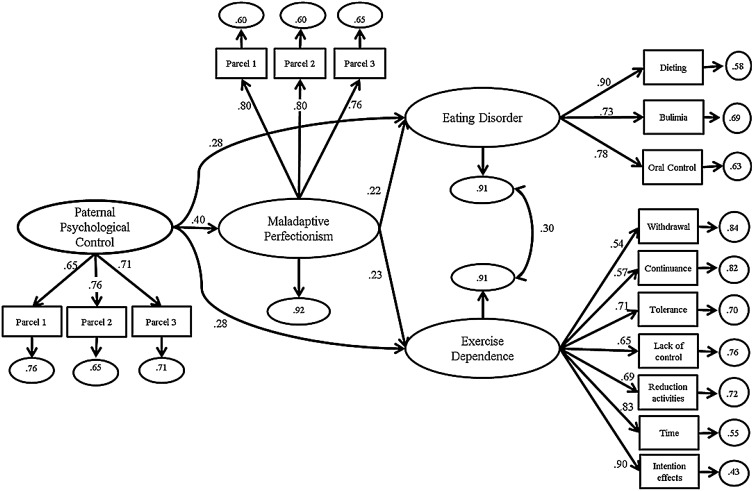

Third, a partial mediation model was assessed by adding a direct path from psychological control to eating disorder and exercise dependence whilst controlling for maladaptive perfectionism, including correlations between the error terms for exercise dependence and eating disorder symptoms. Estimation of this model yielded acceptable fit both for the maternal data, χ2(98) = 167.01, p < .01; CFI = .94; NNFI = .93; SRMR = .06, RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .05–.08), and for the paternal data χ2(98) = 165.48, p < .01; CFI = .94; NNFI = .93; SRMR = .06, RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .05–.08).

This model did not provide a significantly better fit than the full mediation model in the maternal ratings [Δχ2(2) = 1.38; p > .05]. In the paternal ratings instead the partial mediation model does not provide a significantly better fit than the full mediation model [Δχ2(2) = 9.41, p < .05], suggesting that the full mediation model provided the most parsimonious representation of the data only for the maternal model.

Moreover, in the maternal model, the originally significant path from psychological control to eating disorder (β = .11; p > .05), and exercise dependence (β = .10; p > .05) was no longer significant after including maladaptive perfectionism as a mediator. Instead in the paternal model, after including maladaptive perfectionism as a mediator, the paths from psychological control to eating disorders (β = .28; p < .01) and to exercise dependence remained significant (β = .28; p < .05).

In summary, the full mediation model was the most parsimonious and best fitting model for the maternal data (see Figure 1), whilst the partially mediated model was the best fitting model for the paternal data (see Figure 2). In this model, the direct paths from psychological control to eating disorders and exercise dependence were not significant after including the mediator in the maternal model, while they were significant after including the mediator in the paternal model. Furthermore, the indirect relation of psychological control with eating disorders and exercise dependence mediated by maladaptive perfectionism were statistically significant for both maternal and paternal ratings, suggesting that perfectionism was a full mediator in the maternal model while it represented a partial mediation in the paternal model (see Table 2).

Figure 2.

Partial mediation model between paternal psychological control, maladaptive perfectionism, eating disorder and exercise dependence in a male sample. Note: Coefficients shown are standardized path coefficients for the paternal psychological control model in a male sample

Mediation analysis for the female participants

First, a model estimating the direct paths from the predictor (i.e., parental psychological control) to the outcome variable (i.e., eating disorder and exercise dependence) in the female sample was tested, including correlations between the error terms for exercise dependence and eating disorder symptoms. This model did not include maladaptive perfectionism. Estimation of the maternal model, χ2(62) = 168.53, p <.001; CFI = .91; NNFI = .88; SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .10 (90% CI = .08–.12), showed a significant path from psychological control to eating disorder (β = .37; p < .01), and exercise dependence (β = .26; p < .01). Similarly, estimation of the paternal model, χ2(62) = 165.55, p <.01; CFI = .91; NNFI = .88; SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .09 (90% CI = .08–.12), showed a significant path from psychological control to eating disorder (β = .23; p < .01), and exercise dependence (β = .28; p < .01).

Second, a full mediation model with psychological control was tested, that is, a model in which psychological control was related only indirectly to eating disorders and exercise dependence through maladaptive perfectionism, including correlations between the error terms for exercise dependence and eating disorder symptoms. Estimation of this model (see Figure 1) yielded acceptable fit for both the maternal data, χ2(100) = 206.55, p < .01; CFI = .93; NNFI = .91; SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .08 (90% CI = .06–.09), and the paternal data, χ2(100) = 214.83, p < .01; CFI = .92; NNFI = .90; SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .08 (90% CI = .07–.10). Psychological control was related positively to maladaptive perfectionism in both the maternal (β = .63; p < .01) and the paternal model (β = .40; p < .01). In turn, maladaptive perfectionism was related positively to eating disorders (β = .51; p < .01), and exercise dependence (β = .49; p < .01) in the maternal model. Maladaptive perfectionism was also related positively to eating disorders (β = .51; p < .01), and exercise dependence (β = .50; p < .01) in the paternal model.

Third, a partial mediation model by adding a direct path from psychological control to eating disorder and exercise dependence whilst controlling for maladaptive perfectionism and that included correlations between the error terms for exercise dependence and eating disorder symptoms was assessed. Estimation of this model yielded acceptable fit both for the maternal data, χ2(98) = 204.90, p < .01; CFI = .93; NNFI = .91; SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .08 (90% CI = .07–.10), and for the paternal data χ2(98) = 213.94, p < .01; CFI = .92; NNFI = .90; SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .08 (90% CI = .07–.10).

This model did not provide a significantly better fit than the full mediation model in the maternal [Δχ2(2) = 1.65; p > .05], and the paternal ratings [Δχ2(2) = 0.89; p > .05], suggesting that the full mediation model provided the most parsimonious representation of the data.

Moreover, in the maternal model, the originally significant path from psychological control to eating disorder (β = .07; p > .05), and exercise dependence (β = .09; p > .05) was no longer significant after including maladaptive perfectionism as a mediator. Similarly to the maternal model, in the paternal model, the originally significant paths from psychological control to eating disorder (β = .04; p > .05) and exercise dependence (β = .09; p > .05) were no longer significant after including maladaptive perfectionism as a mediator.

In summary, the full mediation model was the most parsimonious and best fitting model for the maternal data and the paternal data (see Figure 1). In this model, the direct paths from psychological control to eating disorders and exercise dependence were not significant after including the mediator in both the maternal and paternal models, suggesting that perfectionism was a full mediator in both of the models. While the indirect relation of psychological control with eating disorders and exercise dependence mediated by maladaptive perfectionism were statistically significant for both the maternal and paternal ratings (see Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Path estimates, SEs and 95% CIs for models in the male sample

| β | B-SE | Lower bound (BC) 95% CI | Upper bound (BC) 95% CI | |

| Maternal model | ||||

| Direct effect | ||||

| Psychological Control → Maladaptive Perfectionism | .48 | .08 | .30 | .62 |

| Psychological Control → Eating Disorder | .11 | .13 | −.14 | .34 |

| Psychological Control → Exercise Dependence | .11 | .11 | −.14 | .33 |

| Maladaptive Perfectionism → Eating Disorder | .28 | .13 | .03 | .51 |

| Maladaptive Perfectionism → Exercise Dependence | .28 | .11 | .07 | .49 |

| Indirect effect via maladaptive perfectionism | ||||

| Psychological Control → Eating Disorder | .13 | .07 | .02 | .27 |

| Psychological Control → Exercise Dependence | .13 | .06 | .04 | .28 |

| Paternal model | ||||

| Direct effect | ||||

| Psychological Control → Maladaptive Perfectionism | .40 | .11 | .19 | .61 |

| Psychological Control → Eating Disorder | .29 | .12 | .05 | .54 |

| Psychological Control → Exercise Dependence | .29 | .11 | .04 | .48 |

| Maladaptive Perfectionism → Eating Disorder | .21 | .10 | .02 | .43 |

| Maladaptive Perfectionism → Exercise Dependence | .21 | .10 | .01 | .40 |

| Indirect effect via maladaptive perfectionism | ||||

| Psychological Control → Eating Disorder | .09 | .05 | .02 | .22 |

| Psychological Control → Exercise Dependence | .08 | .05 | .01 | .22 |

Note: B-SE = bootstrapped standards errors; BC 95% CI = bias corrected-confidence interval.

Table 4.

Path estimates, SEs and 95% CIs for models in the female sample

| β | B-SE | Lower bound (BC) 95% CI | Upper bound (BC) 95% CI | |

| Maternal model | ||||

| Direct effect | ||||

| Psychological Control → Maladaptive Perfectionism | .63 | .06 | .50 | .75 |

| Psychological Control → Eating Disorder | .09 | .16 | −.21 | .42 |

| Psychological Control → Exercise Dependence | −.07 | .16 | −.41 | .24 |

| Maladaptive Perfectionism → Eating Disorder | .45 | .14 | .15 | .70 |

| Maladaptive Perfectionism → Exercise Dependence | .54 | .13 | .27 | .79 |

| Indirect effect via maladaptive perfectionism | ||||

| Psychological Control → Eating Disorder | .28 | .09 | .10 | .47 |

| Psychological Control → Exercise Dependence | .34 | .10 | .15 | .57 |

| Paternal model | ||||

| Direct effect | ||||

| Psychological Control → Maladaptive Perfectionism | .40 | .09 | .22 | .56 |

| Psychological Control → Eating Disorder | .07 | .12 | −.16 | .32 |

| Psychological Control → Exercise Dependence | .10 | .13 | −.15 | .38 |

| Maladaptive Perfectionism → Eating Disorder | .48 | .10 | .24 | .66 |

| Maladaptive Perfectionism → Exercise Dependence | .45 | .10 | .24 | .62 |

| Indirect effect via maladaptive perfectionism | ||||

| Psychological Control → Eating Disorder | .19 | .06 | .10 | .32 |

| Psychological Control → Exercise Dependence | .18 | .06 | .09 | .31 |

Note: B-SE = bootstrapped standards errors; BC 95% CI = bias corrected-confidence interval.

Multiple group analysis

As a subsidiary to the main analyses, we tested the equality of the model parameters across gender. Specifically, we compared the revised model unconstrained across gender with a nested model in which all factor loadings, path coefficients, and the error covariances of the two partial mediation models were constrained to be invariant across gender. The fit indices of the constrained maternal model, χ2(214) = 408.22; S-B χ²(214) = 355.97, p < .05, R-CFI = .93; R-RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .05–.07), did not significantly differ from the unconstrained model, χ2(196) = 371.90; S-B χ²(196) = 327.70, p < .05, R-CFI = .93; R-RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .05–.07). Similar results were provided for the paternal model, where the fit indices of the constrained model, χ²(214) = 413.58, S-B χ²(214) = 354.45, p < .05, R-CFI = .93; R-RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .05–.07), did not significantly differ from the unconstrained model, χ²(196) = 379.41, S-B χ²(196) = 329.16, p < .05, R-CFI = .93; R-RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .05–.07), indicating measurement equivalence across gender both for the maternal [Δχ2(18) = 28.46, p > .05; ΔCFI = .006] and paternal model [Δχ2(18) = 25.87, p > .05; ΔCFI = .005].

Discussion

Researchers have highlighted the necessity of exploring the mechanisms that establish the relationship between psychological control and personal functioning (Barber & Harmon, 2002; Costa, Soenens, et al., 2015; Gugliandolo et al., 2014; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, et al., 2005). Costa, Hausenblas, et al. (2015) found that parental psychological control may have an effect on the development of exercise dependence in habitual exercisers. Several studies have shown that psychological control create a vulnerability to maladaptive patterns of development through a perfectionism orientation (Soenens et al., 2006; Soenens et al., 2008). Although research has yielded evidence for the intervening role of perfectionism in associations between parental control and eating disorders (Soenens et al., 2008), this hypothesis has not been fully addressed in research on habitual exercisers and on exercise dependence symptoms. The aim of our study, therefore, was to examine both perceived parental psychological control and perfectionism in relation to eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms.

The first results of the present study indicate that there is a significant relationship between parental psychological control and both exercise dependence and eating disorder symptoms. These findings are similar to the findings of Soenens et al. (2008) and Costa, Hausenblas, et al. (2015), in that paternal psychological control was positively related to eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms. The results of our study give further insight into these findings suggesting that both paternal and maternal psychological control is related to eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms. It is plausible that maternal psychological control could have a greater impact on eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms indirectly, rather than directly, through its relationship with other variables (e.g., maladaptive perfectionism; Costa, Hausenblas, et al., 2015; Pole, Waller, Stewart, & Parkin‐Feigenbaum, 1988; Soenens et al., 2008; Vandereycken, 1994). Second, and consistent with previous research, it was found that psychological control, both maternal and paternal, predicted maladaptive perfectionism (Soenens, Elliot, et al., 2005; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, et al., 2005; Soenens et al., 2008), while maladaptive perfectionism, predicted eating disorder symptoms (Bulik et al., 2003; Flett et al., 1995; Halmi et al., 2000; Soenens et al., 2008) and exercise dependence symptoms (Hagan & Hausenblas, 2003; Hausenblas & Symons Downs, 2002b; Symons Downs et al., 2004).

The current study also hypothesized an effect of maladaptive perfectionism as a mediator in the relationship between psychological control and eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms. Results confirmed the mediating role of maladaptive perfectionism as a full mediator for eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms for both male and female habitual exercisers in the maternal data. Furthermore, in the paternal data, maladaptive perfectionism mediated the relationships between paternal psychological control and eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms as full mediator for the female participants and as partial mediator for the male participants. In according with the suggestions of Soenens et al. (2008), maladaptive perfectionism, in fact, would be the result of a family context in which parents approve their child’s behaviour only when meet their harsh standards and criticize their child when fails. As a consequence children gradually engage in negative self-evaluations and learn to impose these high and rigid standards on themselves (Flett et al., 2002; Soenens et al. 2008). For this reason, the experience of psychological control would yield exercisers sensitive for the development of an enduring perfectionist orientation. In habitual exercisers, perfectionism could be characterized by restrictiveness and desire for control. These typical overcontrolled personality features of perfectionism, in association with the worries about being unable to adhere their standards for performances and body appearance, could lead to a rigid focus both on eating and exercise, with an escalating pattern of disordered eating and excessive exercise behaviors (Hall, 2006; Shafran et al., 2002; Soenens et al., 2008).

Finally, consistent with previous research, men reported more exercise dependence symptoms than women, and women reported more eating disorder symptoms than men (Berczik et al., 2012; Costa, Hausenblas, et al., 2013; Lewinsohn, Seeley, Moerk, & Striegel‐Moore, 2002; Striegel‐Moore et al., 2009). A possible explanation could be that, from a body image perspective, exercise allow to meet in men the societal standard of muscular psysique, with the risk to develop a "drive for muscularity". In female, instead, exercise to yield their societal standard of psysique should be accompanied by calorie reduction, with the risk to develo a "drive for thinness" (Hausenblas & Fallon, 2002; McCreary & Sasse, 2000; Vocks, Hechler, Rohrig, & Legenbauer, 2009). Furthermore, the differing nature of each relationship between mother, father, sons and daughters might influence the link between psychological control and adjustment (Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2010; Steinberg, 2001). In our study separate analyses were conducted for male and female habitual exercisers and the effects of psychological control were differentiated between maternal and paternal perceived psychological control. However structural associations were relatively analogous in maternal and paternal models. This result was consistent with previous studies that examinated the dynamics of parental psychological control in fathers and mothers (Barber & Harmon, 2002). In fact, both for men and women the relations between maternal psychological control and eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms were mediated by maladaptive perfectionism. The same results were found for maternal psychological control in male habitual exercisers, while paternal psychological control in male habitual exercisers was partially mediated by maladaptive perfectionism in its relation with eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms. This pattern suggests independent additive effects. Consequently, habitual exercisers’ eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms were directly predicted by paternal psychological control and indirectly through the mediation of maladaptive perfectionism. Paternal psychological control could promote maladaptive perfectionism leading to the development of eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms. However, on the other hand, the association between parental psychological control and eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms could also depend on not clear aspects that may be investigated in future studies. In our view, the different pattern of relationships between the paternal and maternal models in men is mainly due to the fact that paternal psychological control seems to have a more pronounced and systematic association with eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms (Costa, Hausenblas, et al., 2015; Soenens et al., 2008). In fact, even though fathers may be less involved in parenting than mothers overall, they may step in when more serious child-rearing problems arise and when conflict and negativity are more likely (May, Kim, McHale, & Crouter, 2006).

The implications of these findings could be a very important in prevention and treatment efforts. The deleterious effects of parental psychological control, both on eating disorder and on exercise dependence symptoms (Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2010), require the implementation of targeted interventions to educate parents in using fewer intrusions and parental autonomy support, as opposed to psychological control. It is important to educate parents about psychological control being a universally negative parenting strategy and to help parents identify and reduce the use of such dysfunctional practices. Parent training could be used to help parents to get to practice autonomy supportive skills by taking part in various exercises from common situations in familial daily living. Finally, results of this study provide evidence for factors of relevance for both exercise dependence and eating disorders that could serve as focal points for integrated prevention interventions. Results of the study suggest that the therapist and client could work together to identify and correct the client’s maladaptive perfectionism thought processes that result in maladaptive eating or exercise behavior. This can involve helping a client to understand the development of his or her maladaptive perfectionism thought and how it can result in eating disorder or exercise dependence symptoms.

The present study shows a number of shortcomings that need to be addressed in future research. First, the data were collected at one time point and not across multiple time points as it should be done for a true mediational analysis. Because of the cross-sectional and self-report design of our study, we cannot establish either the direction or causality of the effects. As well, the self-report data may have intrinsic limitations such as social desirability, so the use of objective and multi-informant measures and experimental designs are encouraged (Gugliandolo, Costa, Cuzzocrea, Larcan, & Petrides, 2015). Although our sample consisted of habitual exercisers, this sample was deemed justified, as eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms are prevalent in this population (e.g., Costa, Hausenblas, et al., 2013) and because psychological control is a risk factor for eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms in this population (e.g., Costa, Hausenblas, et al., 2015; Soenens et al. 2008). Future researchers are encouraged to rely on larger and more heterogeneous samples, including clinical populations, to explore the generalizability of the hypothesized model.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our study findings offer an original contribution for examining the parents’ role in the development of eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms in habitual exercisers. This is the first study that examines the mediational role of maladaptive perfectionism in the relation between parental psychological control and eating disorder and exercise dependence symptoms in a sample of habitual exercisers, showing that the intrusive and controlling parenting seems to generate a vulnerability to perfectionism and maladjustment psychopathology that in both male and female habitual exercisers could lead in eating disorder and exercise dependence. Moreover, our study furthers the examination of the role of parental psychological control in exercise context. A more detailed understanding of the various mechanisms, individual and/or interactional, that are operating will provide psychologists with a well-founded theoretical basis for therapeutic intervention implementation, and support to reduce the potential risk of experiencing unhealthy eating and exercise behaviors.

Authors’ contribution

SC assisted with generation of the initial draft of the manuscript, data analyses, and manuscript editing; HH assisted with manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, interpretation of data, study design and concept; PO assisted with manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, study design and concept; FC assisted with data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript editing; RL assisted with data interpretation, manuscript editing, and study supervision. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors report that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: No financial support was received for this study.

References

- Adams J. (2009). Understanding exercise dependence. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 39, 231–240. doi: 10.1007/s10879-009-9117-5 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Bamber D. J., Cockerill I. M., Rodgers S., Carroll D. (2003). Diagnostic criteria for exercise dependence in women. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 37, 393–400. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.5.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child development, 67, 3296–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber B. K., Buehler C. (1996). Family cohesion and enmeshment: Different constructs, different effects. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58, 433–441. [Google Scholar]

- Barber B. K., Harmon E. L. (2002). Violating the self: Parental psychological control of children and adolescents. In Barber B. K. (Ed.), Intrusive parenting: How psychological control affects children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Barber B. K., Stolz H. E., Olsen J. A. (2005). Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, method, and culture. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 70, 1–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. M., Kenny D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berczik K., Szabó A., Griffiths M. D., Kurimay T., Kun B., Urbán R., Demetrovics Z. (2012). Exercise addiction: Symptoms, diagnosis, epidemiology, and etiology. Substance Use & Misuse, 47, 403–417. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.639120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling P. J., Israeli A. L., Antony M. M. (2004). Is perfectionism good, bad, or both? Examining models of the perfectionism construct. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 1373–1385. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00235-6 [Google Scholar]

- Boone L., Soenens B. Braet C. Goossens L. (2010). An empirical typology of perfectionism in early-to-mid adolescents and its relation with eating disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 686–691. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik C. M. Devlin B., Bacanu S. A. Thornton L. Klump K. L. Fichter M. M. Kaye W. H. (2003). Significant linkage on chromosome 10p in families with bulimia nervosa. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 72, 200–207. doi: 10.1086/345801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman D. L., MacCallum R. C. (2005). Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40, 235–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa S., Coppolino P. Oliva P. (2015). Exercise dependence and maladaptive perfectionism: The mediating role of basic psychological needs. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. doi: 10.1007/s11469-015-9586-6

- Costa S., Cuzzocrea F., Hausenblas H. A., Larcan R., Oliva P. (2012). Psychometric examination and factorial validity of the exercise dependence scale–revised in Italian exercisers. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 1, 186–190. doi: 10.1556/JBA.1.2012.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa S., Hausenblas H. A., Oliva P., Cuzzocrea F., Larcan R. (2015). Perceived parental psychological control and exercise dependence symptoms in competitive athletes. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13, 59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11469-014-9512-3 [Google Scholar]

- Costa S., Hausenblas H. A., Oliva P., Cuzzocrea F., Larcan R. (2013). The role of age, gender, mood states and exercise frequency on exercise dependence. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2, 216–223. doi: 10.1556/JBA.2.2013.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa S., Oliva P. (2012). Examining relationship between personality characteristics and exercise dependence. Review of Psychology, 19, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Costa S., Soenens B., Gugliandolo M. C., Cuzzocrea F., Larcan R. (2015). The mediating role of experiences of need satisfaction in associations between parental psychological control and internalizing problems: A study among Italian college students. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1106–1116. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-9919-2 [Google Scholar]

- Doninger G. L., Enders C. K., Burnett K. F. (2005). Validity evidence for Eating Attitudes Test scores in a sample of female college athletes. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 9, 35–49. doi: 10.1207/s15327841mpee0901_3 [Google Scholar]

- Dotti A., Lazzari R. (1998) Validation and reliability of the Italian EAT-26. Eating and Weight Disorders, 3, 188–194. doi: 10.1007/bf03340009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley D. M., Blankstein K. R. Masheb R. M. Grilo C. M. (2006). Personal standards and evaluative concerns dimensions of “clinical” perfectionism: A reply to Shafran et al. (2002, 2003) and Hewitt et al. (2003). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 63–84. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enns M. W., Cox B. J., Larsen D. K. (2000). Perceptions of parental bonding and symptom severity in adults with depression: Mediation by personality dimensions. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 45, 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippello P., Sorrenti L., Buzzai C., Costa S. (2015). Perceived parental psychological control and learned helplessness: The role of school self-efficacy. School Mental Health, 7, 298–310. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9151-2 [Google Scholar]

- Flett G. L., Hewitt P. L., Blankstein K. R., Mosher S. W. (1995). Perfectionism, life events, and depressive symptoms: A test of a diathesis-stress model. Current Psychology, 14, 112–137. doi: 10.1007/bf02686885 [Google Scholar]

- Flett G. L., Madorsky D., Hewitt P. L., Heisel M. J. (2002). Perfectionism cognitions, rumination, and psychological distress. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 20, 33– 47. doi: 10.1023/A:1015128904007 [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth M., Moniz S., Kim S. R. (2011). Clarifying exercise addiction: Differential diagnosis, co-occurring disorders, and phases of addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(10), 4069– 4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R. O., Marten P., Lahart C., Rosenblate R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449–468. doi: 10.1007/bf01172967 [Google Scholar]

- Gardner R. M., Stark K., Friedman B. N., Jackson N. A. (2000). Predictors of eating disorder scores in children ages 6 through 14: A longitudinal study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 49, 199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00172-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner D. M., Olmsted M. P., Bohr Y., Garfinkel P. E. (1982). The eating attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12, 871–878. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700049163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner D. M., Olmstead M. P., Polivy J. (1983). Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 2, 15–34. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00172-0 [Google Scholar]

- Gugliandolo M. C., Costa S., Cuzzocrea F., Larcan R. (2014). Trait emotional intelligence as mediator between psychological control and behaviour problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 2290–2300. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-0032-3 [Google Scholar]

- Gugliandolo M. C., Costa S., Cuzzocrea F., Larcan R., Petrides K. V. (2015). Trait emotional intelligence and behavioral problems among adolescents: A cross-informant design. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.032 [Google Scholar]

- Hagan A. L., Hausenblas H. A. (2003). The relationship between exercise dependence symptoms and perfectionism. American Journal of Health Studies, 18, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hall H. K. (2006). Perfectionism: A hallmark quality of world class performers, or a psychological impediment to athletic development. Essential Processes for Attaining Peak Performance, 1, 178–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hall H. K., Hill A. P., Appleton P. R., Kozub S. A. (2009). The mediating influence of unconditional self-acceptance and labile self-esteem on the relationship between multidimensional perfectionism and exercise dependence. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10, 35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.05.003 [Google Scholar]

- Hall H. K., Kerr A. W., Kozub S. A., Finnie S. B. (2007). Motivational antecedents of obligatory exercise: The influence of achievement goals and multidimensional perfectionism. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 8, 297–316. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.04.007 [Google Scholar]

- Halmi K. A., Sunday S. R., Strober M., Kaplan A., Woodside D. B., Fichter M., Kaye W. H. (2000). Perfectionism in anorexia nervosa: Variation by clinical subtype, obsessionality, and pathological eating behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1799–1805. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausenblas H. A., Fallon E. A. (2002). Relationship among body image, exercise behavior, and exercise dependence symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 32, 179–185. doi: 10.1002/eat.10071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausenblas H. A., Symons Downs D. (2002a). Exercise dependence: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 3, 89–123. doi: 10.1016/s1469-0292(00)00015-7 [Google Scholar]

- Hausenblas H. A., Symons Downs D. (2002b). How much is too much? The development and validation of the exercise dependence scale. Psychology and Health, 17, 387–404. doi: 10.1080/0887044022000004894 [Google Scholar]

- Hoek H. W. (2006). Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19, 389–394. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000228759.95237.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N. (1997). Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 599–610. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.65.4.599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. T., Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [Google Scholar]

- Klein D. A., Bennett A. S., Schebendach J., Foltin R. W., Devlin M. J., Walsh B. T. (2004). Exercise “addiction” in anorexia nervosa: Model development and pilot data. CNS Spectrums, 9, 531–537. doi: 10.1017/S1092852900009627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig L. J., Wasserman E. L. (1995). Body image and dieting failure in college men and women: Links between depression and eating problems. Sex Roles, 32, 225–249. doi: 10.1007/BF01544790 [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H. C., Stice E., Kazdin A., Offord D., Kupfer D. (2001). How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 848–856. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P. M., Seeley J. R., Moerk K. C., Striegel‐Moore R. H. (2002). Gender differences in eating disorder symptoms in young adults. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 32, 426–440. doi: 10.1002/eat.10103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little T. D., Cunningham W. A., Shahar G., Widaman K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo C. (2008). Adattamento italiano della multidimensional perferctionism scale (mps) [Italian adaptation of the multidimensional perfectionism scale (mps)]. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale, 14, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H. W., Hau K. T., Balla J. R., Grayson D. (1998). Is more ever too much: The number of indicators per factor in confirmatory factor analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 33, 181–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May A. L., Kim J. Y., McHale S. M., Crouter A. (2006). Parent–adolescent relationships and the development of weight concerns from early to late adolescence. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39, 729–740. doi: 10.1002/eat.20285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary D. R., Sasse D. K. (2000). An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. Journal of American College Health, 48, 297–304. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K. J., Mesagno C. (2014). Personality traits and exercise dependence: Exploring the role of narcissism and perfectionism. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12, 368–381. doi: 10.1080/1612197x.2014.932821 [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. R. (2012). I don’t want to get involved: Shyness, psychological control, and youth activities. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/0265407512448266 [Google Scholar]

- Oliva P., Costa S., Larcan R. (2013). Physical self-concept and its relationship to exercise dependence symptoms in young regular physical exercisers. American Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 1, 1–6. doi: 10.12691/ajssm-1-1-1 [Google Scholar]

- Paulson L. R., Rutledge P. C. (2014). Effects of perfectionism and exercise on disordered eating in college students. Eating Behaviors, 15, 116–119. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pole R., Waller D. A., Stewart S. M., Parkin‐Feigenbaum L. (1988). Parental caring versus overprotection in bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 7, 601–606. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.11.005 [Google Scholar]

- Polivy J., Herman C. P. (2002). Causes of eating disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 187–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber K., Hausenblas H. A. (2015). The truth about exercise addiction: Understanding the dark side of thinspiration. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Shafran R., Cooper Z., Fairburn C. G. (2002). Clinical perfectionism: A cognitive–behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 773–791. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00059-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafran R., Mansell W. (2001). Perfectionism and psychopathology: A review of research and treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 879–906. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00072-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout P. E., Bolger N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.4.422 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B., Elliot A. J., Goossens L., Vansteenkiste M., Luyten P., Duriez B. (2005). The intergenerational transmission of perfectionism: Parents’ psychological control as an intervening variable. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 358–366. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B., Luyckx K., Vansteenkiste M., Luyten P., Duriez B., Goossens L. (2008). Maladaptive perfectionism as an intervening variable between psychological control and adolescent depressive symptoms: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 465–474. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B., Vansteenkiste M. (2010). A theoretical upgrade of the concept of parental psychological control: Proposing new insights on the basis of self-determination theory. Developmental Review, 30, 74–99. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2009.11.001 [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B., Vansteenkiste M., Duriez B., Goossens L. (2006). In search of the sources of psychologically controlling parenting: The role of parental separation anxiety and parental maladaptive perfectionism. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 539–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00507.x [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B., Vansteenkiste M., Luyten P. (2010). Toward a domain-specific approach to the study of parental psychological control: Distinguishing between dependency-oriented and achievement-oriented psychological control. Journal of Personality, 78, 217–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B., Vansteenkiste M., Luyten P., Duriez B., Goossens L. (2005). Maladaptive perfectionistic self-representations: The mediational link between psychological control and adjustment. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 487–498. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.008 [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. (2001). We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11, 1–19. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00001 [Google Scholar]

- Striegel‐Moore R. H., Rosselli F., Perrin N., DeBar L., Wilson G. T., May A., Kraemer H. C. (2009). Gender difference in the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42, 471–474. doi: 10.1002/eat.20625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons Downs D., Hausenblas H. A., Nigg C. R. (2004). Factorial validity and psychometric examination of the exercise dependence scale-revised. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 8, 183–201. doi: 10.1207/s15327841mpee0804_1 [Google Scholar]

- Vandereycken W. (1994). Emergence of bulimia nervosa as a separate diagnostic entity: Review of the literature from 1960 to 1979. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16, 105–116. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199409)16:2<105::aid-eat2260160202>3.0.co;2-e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocks S., Hechler T., Rohrig S., Legenbauer T. (2009). Effects of a physical exercise session on state body image: The influence of pre-experimental body dissatisfaction and concerns about weight and shape. Psychology and Health, 24, 713–728. doi: 10.1080/08870440801998988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmijewski C. F., Howard M. O. (2003). Exercise dependence and attitudes toward eating among young adults. Eating Behaviors, 4(10), 181– 195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]