Abstract

Acquired bone marrow failure syndromes encompass a unique set of disorders characterized by a reduction in the effective production of mature cells by the bone marrow (BM). In the majority of cases, these syndromes are the result of the immune-mediated destruction of hematopoietic stem cells or their progenitors at various stages of differentiation. Microbial infection has also been associated with hematopoietic stem cell injury and may lead to associated transient or persistent BM failure, and recent evidence has highlighted the potential impact of commensal microbes and their metabolites on hematopoiesis. We summarize the interactions between microorganisms and the host immune system and emphasize how they may impact the development of acquired BM failure.

Keywords: bone marrow failure syndromes, aplastic anemia, virus-induced anemia, microbioma, microbe immunity

Introduction

Bone marrow failure syndromes (BMFS) are a group of heterogeneous disorders defined by the loss or malfunction of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Deficient cell production can be seen across multiple lineages, resulting in a loss of erythrocytes, granulocytes, or platelets. Distinct syndromes are, therefore, defined by the specific cells affected and include pure red cell aplasia (PRCA), amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenic purpura, aplastic anemia (AA), and myelodysplastic syndrome. AA, the paradigm BMFS, is characterized by a deficiency of HSCs resulting in peripheral pancytopenia and hypoplastic bone marrow (BM) (1, 2). This may occur as the result of inherited abnormalities as seen in syndromes like Fanconi anemia, dyskeratosis congenital, and Shwachman–Diamond syndrome, or may be an acquired phenomena (3).

The primary mechanism of acquired AA centers on the immune-mediated destruction of HSCs, and highly immunosuppressive therapies provide excellent and durable clinical responses (4). Several immune cell abnormalities are also commonly found in patients, including dysregulated CD4+, CD8+, and Th-17 T-cell responses, as well as reduced numbers of regulatory T-cells. Furthermore, many patients have elevated circulating levels of inflammatory or myelosuppressive cytokines like interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF)-α, and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) (5).

Despite efforts that have revealed circulating autoantibodies in acquired AA patients (6–8), the identification of autoantigens able to elicit cytotoxic T-cell responses and breach immune tolerance leading to the destruction of HSCs has been difficult. Current theories suggest that, similar to other autoimmune diseases, the initial immune response may be triggered by drugs, chemicals, or pathogens, or through the generation of neoantigens via epigenetic mechanisms (4, 5, 9, 10). Interestingly, autoimmune illnesses like rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematous, or ulcerative colitis sometimes precede the development of acquired AA (11–13). As transient and persistent BM hypoplasia have been linked to various microorganisms (14), dysbiosis between the gut microbiota and immune system may serve as an initial insult in the development of BMFS (11).

We herein report an overview of the complex interplay between microorganisms, the immune system, and hematopoiesis and discuss the implications these interactions may have in the pathogenesis of acquired BMFS.

Regulation of Hematopoiesis by Inflammatory Signals

Interplay between HSCs and their microenvironment determines whether or not these cells will undergo differentiation, proliferation, or apoptosis. Secreted factors like erythropoietin, thrombopoietin, IL-3, GM-CSF, and stem cell factor (SCF) positively regulate the HSC maintenance and differentiation during steady-state hematopoiesis (1–3). Surrounding mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and other BM niche components support HSCs and ensure their stem cell phenotype through the release of TGF-β, SCF, CXCL12, and angiopoietin-1 (15).

In response to systemic injury, HSCs are signaled to proliferate and differentiate. HSCs express cytokine, chemokine, and pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) and can be directly triggered by activated immune effector cells, pathogens, or by surrounding stem cells (16, 17). In bacterial infections, the rapid consumption of granulocytes triggers HSCs to proliferate along the myeloid lineage (15, 18). In contrast, viral infections mainly involve IFN-α and IFN-β signaling. Type I IFNs prevent viral replication and induce HSCs to transiently proliferate, whereas persistent type I IFN signaling may lead to HSC exhaustion (19, 20).

Interferon-γ secreted by activated T-cells and NK cells modulates hematopoiesis differentially based on acute on chronic signaling. For instance, HSCs have been shown to enter active cell cycle stages and differentiate in mice treated with IFN-γ. However, chronic IFN-γ stimulation impairs the function of HSCs, leading to the development of cytopenia (21, 22).

Other signaling molecules released during systemic stress may also impact hematopoiesis. TNF-α produced by CD8+ T-cells enhances HSC clonogenicity and prevents HSC apoptosis both in vitro and in vivo (23). IL-6, a pleiotropic cytokine secreted by BM stromal fibroblasts, leads to the expansion of myeloid progenitors and blocks the development of erythroid cells (24). In response to microbial infection, additional cytokines like IL-1, IL-17, and IL-27 may influence blood cell development, particularly through the induction of HSC expansion and granulopoiesis (20, 25).

Many inflammatory signals maintain immune homeostasis and transiently stimulate hematopoiesis in the promotion of the host defenses during stress. However, the prolonged stimulation of HSCs may induce an opposing effect leading to anergy, chronic exhaustion, and apoptosis. Cytopenias associated with chronic inflammatory conditions and autoimmune diseases, therefore, likely stem from the sustained failure of HSC renewal and differentiation (17, 26, 27).

Microbiota and Microbial Metabolites Shape Hematopoiesis

The complex system of bacteria, viruses, and fungi living in the human body is referred to as the microbiota. These commensal organisms colonize multiple body niches, with colonic microorganisms being the most abundant (28–30).

The microbiome and its associated metabolites have recently been functionally linked to hematopoiesis, as evidence suggests that the BM myeloid population strongly correlates with microflora complexity. In germ-free mice, the granulocyte and monocyte populations, but not the lymphoid progenitor populations, increased with greater gut flora complexity (31). A lower microbiota diversity was also associated with an overall worse survival and transplant-related mortality in patients receiving allogenic stem cell transplantation (32). Additionally, germ-free and antibiotic-treated mice have impaired functional clearance of systemic bacterial infections. Therefore, many have proposed that commensal microbes play a significant role in HSC maintenance and alterations, and the absence of gut microflora may lead to detrimental downstream defects in immunity (33, 34).

Substances like dietary fiber may exert indirect effects on hematopoiesis through shaping microbial composition. For instance, mice given a fiber-rich diet have alterations in Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Bifidobacteriaceae populations. These microbes metabolize fiber to short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and mice treated with SCFA have larger populations of macrophages and dendritic cell precursors in the BM (35). In this model, high-fiber diet mice had increased circulating SCFAs and were found to have protection against allergic inflammatory lung diseases compared to low-fiber diet, low-level circulating SCFA animals (35).

Pathogen recognition receptors found on HSCs, including toll-like receptors 2, 3, 4, 7, and 9, enable HSCs to recognize and respond to various pathogen-derived products (36, 37). Quiescent HSCs are activated upon acute exposure to these pathogens or products and in turn proliferate. In contrast, chronic exposure to systemic TLR ligands appears to have myelosuppressive effects, as supported by HSC exhaustion seen in mice exposed to repeated administrations of low-dose LPS for 6 weeks (38). Frequent gut microbe translocation, coupled with persistent, detectable serum LPS found in HIV infection has been proposed as mechanism for HIV-related myelosuppression (36). Furthermore, TLR4 may be activated by fatty acids and high levels of circulating metabolites, as found in patients with chronic metabolic syndrome (39). Kell and Pretorius have also proposed that bacterial translocation from dormant bacterial reservoirs provide a persistent source of low-grade inflammation via immune-mediated signals triggered by LPS and other pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (40). This supports the strong association between altered gut microbiota and various autoimmune diseases and may underscore the frequent association of ulcerative colitis, a disease characterized by high bacterial leakage, with BMFS (11).

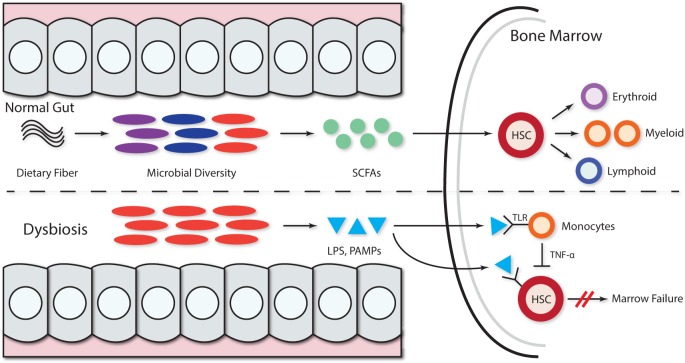

The association between alterations in the gut microbiome and BMFS has not been systematically investigated. However, evidence for the pivotal role of gut flora in immune system priming, education, and regulation (41, 42) suggests that microbiota, their metabolic products, or PAMPs can lead to the development of hematological disorders (34). In patients with acquired BMFS, microbes and their metabolites may inhibit hematopoiesis and enact negative downstream effects on HSCs (Figure 1). However, the details of the mechanisms have yet to be elucidated.

Figure 1.

Microbiota and microbial metabolites can shape hematopoiesis and the immune response. Commensal microbes promote the maintenance of both hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and precursor myeloid cells. The absence of commensal microbes leads to defects in several innate immune cell populations, including neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages. Feeding mice a diet rich in fiber changed the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes and Bifidobacteriaceae. The presence of a complex intestinal microbiota specifically amplifies myelopoiesis in the bone marrow (BM). Dietary fiber is metabolized by gut microbiota, thereby increasing the levels of circulating short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and promoting the growing of myeloid precursors without affecting lymphoid progenitors in the BM. In the context of dysbiosis, the growth of pathogenic microbes acts as dormant bacterial reservoir that provides a source of persistent low-grade inflammation mediated by LPS and other pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that persistently stimulate hematopoietic stem progenitor cells via pathogen recognition receptors like TLR (TLR4, TLR7, and TLR9), leading to hematopoiesis inhibition. The LPS stimulation of TLR monocytes induces TNF-alpha secretion, and this persistent stimulation of HPSCs may further inhibit hematopoiesis via exhaustion.

BM Failure Induced by Microbial Infection

Several microbial infections have been linked to the development of acquired BMFS. The mechanisms underlying how pathogens induce hematopoietic dysfunction are poorly understood for most diseases, except parvovirus B19 infection-related aplasia (43). Many hypotheses for disease pathogenesis center on the direct infection of HSCs, viral recognition by HSCs via PRRs, inflammation-mediated effects by surrounding cells or response to changes in the stem cell microenvironment (15, 19, 20, 44). Cytomegalovirus (CMV), parvovirus B19, and the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) induce HSC injury through direct toxic effects from pathogens (14, 45). However, the majority of pathogen-related cases are thought to be due to the excessive activation of immune effector cells, leading to an overwhelming release of myelosuppressive cytokines and negative proliferation signaling to HSCs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Microbes triggering bone marrow (BM) failure.

| Microbe | Effects on hematopoiesis | Mechanism(s) | Target cells | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | ||||

| Parvovirus B19 | Various cytopenias | Apoptosis of target cells | Erythroid progenitor | (43, 47–50) |

| Anemia | Excessive inflammatory signals IL1-β, IL6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interferon (IFN)-γ | |||

| Pure red cells aplasia | ||||

| Aplastic anemia (AA) | ||||

| Thrombocytopenic Purpura | ||||

| Epstein–Barr virus | Thrombocytopenia | Excessive inflammatory signals: TNF-α and IFN-γ | HPSC | (54–58) |

| AA | HPSC inhibition by virus-specific T-cells | T-cells | ||

| Pure red cells aplasia | ||||

| Dengue virus | Leukopenia | Apoptosis of progenitor cells | Hematopoietic stem progenitor cells, megakaryocyte progenitor | (62–65, 69, 70) |

| Thrombocytopenia | Excessive inflammatory signal: multiple cytokines | |||

| Severe AA | ||||

| HAAA | AA | Excessive inflammatory signals | Indirectly HPSC? | (74–76) |

| T-cell activation | ||||

| Multiple cytokines | ||||

| Cytomegalovirus | AA | Stromal function failure | Mesenchymal stem cells | (77, 78) |

| Anemia | ||||

| Human herpes virus-6 | Anemia | Apoptosis of target cells? | Granulocyte macrophage | (79, 80) |

| Pancytopenia | Megakaryocyte progenitors | |||

| HIV | Anemia | Excessive growth of bacterial | HPSC | (36, 40) |

| Sustained activation of pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), TLRs by LPS or other pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) | ||||

| Bacteria | ||||

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum | Pancytopenia | Excessive inflammatory signals | Circulating granulocyte | (85–88) |

| Myelosuppressive cytokines | ||||

| Ehrlichia chaffeensis | Pancytopenia | Granulocyte | (89, 90) | |

| Anemia | ||||

| Thrombocytopenia | ||||

| Tuberculosis | Pancytopenia | Granuloma infiltration in BM | BM niche | (91–93) |

| Maturation arrest? | ||||

| Hypersplenism? | HPSC? | |||

| Histiocytic hyperplasia? | ||||

| Dysbiosis | Anemia? | Persistent release of PAMPs? | HPSC? | (11, 34, 36, 38, 40) |

| AA? | Sustained stimulation of HPSCs via PRRs? | |||

Parvovirus B19-Induced BM Failure

Human parvovirus B19 (B19V) is a small DNA erythrovirus associated classically with fifth disease or erythema infectiosum (46). Primarily spread via respiratory droplets, the virus targets erythroid progenitors in vivo (43). In vitro, the virus is propagated in primary erythroid progenitors BFU-E and CFU-E, and its replication is enhanced under hypoxic conditions. B19V also induces apoptosis in erythroid progenitors in the BM, resulting in hypoplasia (43). In an immunocompromised host, persistent B19V infection can cause chronic anemia, aplastic crisis, PRCA, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (47, 48).

B19V cytotoxicity appears to be mediated via the NS1 protein, which in turn activates caspase 3, 6, and 8, increasing the erythroid cell sensitivity to apoptosis induced by TNF-α (49). In addition, B19V infection is associated with the systemic activation of monocytes, T-cells, and NK cells and correlates with an elevation in serum inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ (43). B19V infection has also been implicated in autoimmunity, as some patients may develop antibodies, including antinuclear, antiphospholipid, anti-smooth muscle, gastric parietal cell antibodies, and rheumatoid factors (49). Apoptotic bodies generated during B19V infection contain many different self-antigens and may serve as a reservoir of autoimmunity priming during infection (50).

EBV-Induced BM Failure

Epstein–Barr virus remains one of the most common viruses afflicting humans, most frequently causing infectious mononucleosis. EBV-infected cells are also associated with cell transformation and several malignancies, including Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, gastric cancer, and HIV-associated neoplasms, such as hairy cell leukoplakia (51, 52). EBV has also been associated with an increased risk for autoimmune disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (53).

In immunocompromised patients, EBV can be associated with a wide range of hematopoietic effects, including BMF and lymphoproliferative disease (51). Single cell lineage disorders like thrombocytopenia with ITP-like syndrome (54) or PRCA (55) have been found in some patients, while others have shown pancytopenia mimicking acquired AA (56). EBV-induced aplasia likely involves excessive immune activation, as experimental data have shown that activated T-cells exposed to autologous EBV-infected B-cells inhibit HSC growth (57). Clinically, patients with EBV-induced acquired AA may respond well to immunosuppressive therapy, and some suggest it may play a role in idiopathic acquired AA cases (58).

Dengue Virus (DENV)-Induced BM Failure

Five distinct serotypes of DENV, a single-stranded RNA arbovirus, has been identified, and all cause dengue fever. Typically, DENV infection induces multiple hematologic abnormalities, including leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia (59). BM biopsies isolated during DENV infection are characterized by abnormal megakaryopoiesis, reticulocytopenia, and granulocytopenia (60, 61).

Although the pathophysiology of DENV-induced BM failure is not well understood, accumulating evidence indicates a combination of an excessive immune response and viral infection of progenitor cells (62, 63). During the acute phase of infection, DENV infects and proliferates in HSC progenitors and CD61+ megakaryocyte progenitor cells (60, 64), thereby inducing transient BMF (63). In addition, DENV infection is associated with the activation of several innate immune responses, including IFN α/β, MIP-1α/β, viperin, and CXCL-10 release, which may inhibit hematopoiesis (65–68). DENV infection has also been shown to preferentially induce production of IFN type III (IFN-λ1) from human dendritic cells, signaling through TLR-3 (69). Similar to other interferons, IFN-λ1 acts as a myelosuppressive factor (70). As the severity of hematological dysfunction can be quite variable and clinical responses are usually achieved via immunosuppression, efforts aimed at characterizing autoimmune responses during both subclinical and clinically significant infections are needed (62, 63).

Hepatitis-Associated BM Failure (HABMF)

Hepatitis-associated BM failure is a distinct variant usually seen 2 or 3 months following an episode of acute hepatitis (71). Although in some cases this entity has been reported in association with hepatitis A, B, C, E, and G viral infections (71, 72), as well as parvovirus B19, EBV and CMV, most patients with HABMF are negative for all known viruses (71). HABMF can be self-limited but often is severe and even fulminant (71, 72); however, the severity appears to be independent of the age, sex, or severity of hepatitis (73). Typically, both the hematologic abnormalities and liver function parameters improve with immunosuppressive therapies (74). When HABMF manifests as severe AA, it represents a life-threatening condition that requires urgent hematological therapy with supportive care and stem cells transplantation (72). Several immunological abnormalities have been documented in patients with HABMF, including increased soluble IL-2 receptor, low ratios of CD4+/CD8+ cells, high percentages of CD8+ cells, and reduced proportions of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cells (74, 75). Notably, clonal expansion of T-cells with conserved antigen specificity has been found in HABMF patients (76), suggesting that abnormal immune responses underlie the disease and viral antigens may elicit T-cell responses that cross-react with antigens expressed by HSCs.

Other Virus-Related BM Failure

Other viruses can also induce BMFS via similar mechanisms in many patients. For instance, several cases of CMV-associated BMFS have been documented, and experimental data have shown CMV infection and replication in MSCs, along with an impaired stromal function (77, 78). Anecdotic associations between human herpes virus 6 with BMFS, mainly in the posttransplantation setting, have been also reported (79) and appear to be related to the direct viral injury of granulocytes, macrophages, and megakaryocyte progenitors in vitro (80). Interestingly, respiratory syncytial virus has also been shown to infect and replicate in human BM stromal cells (81), although its association with resultant BMF does not appear to be common.

Marrow Aplasia and Bacterial Infections

Bacterial infection of HSCs is uncommon, as these cells are rare, quiescent and reside in a protected microenvironment with surrounding MSCs. Stromal elements are capable of inhibiting the growth of several Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (82). Additionally, in vitro experiments have suggested that HSCs may be resistant to intracellular bacteria like Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enterica, and Yersinia enterocolitica (83). These findings are consistent with clinical observations that bacterial pathogens are rarely associated with direct hematopoietic dysfunction. Notably, human CD34+ hematopoietic stem progenitor cells exposed to Escherichia coli in vitro produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, via NFκB activation (84), although the implications of these observations in the clinical setting are unknown.

One of the best characterized myelosuppressive pathogens is Anaplasma phagocytophilum, which causes granulocytic anaplasmosis or ehrlichiosis (85). This Gram-negative bacterium infects granulocytes and persists primarily within circulating granulocytes (86, 87), and infection typically results in multiple cytopenias, including anemia, leucopenia, and thrombocytopenia (86). Mouse models of infection show profound and rapid multilineage deficits in proliferation and differentiation, including B-cell depletion, erythroid depletion, granulocytic hyperplasia, and a significant downregulation of CXCL12 in the BM. These defects are accompanied by induction of myelosuppressive cytokine release such as MCP-1, MIP-2, TNF-α, and IL-6. The absence of infectious particles in the BM compartment suggests that hematopoietic suppression stems from the systemic activation of inflammatory signaling rather than direct infection (88).

Ehrlichia chaffeensis causing monocyte ehrlichiosis is also associated with the development of multiple cytopenias (89). Mouse models have supported the notion that microbial infection may lead to anemia, thrombocytopenia, and BM hypocellularity. Furthermore, in this model, the number of committed progenitors, including erythroid, granulocyte, and monocyte progenitors, in the BM was significantly fewer than in control mice (90).

Finally, pancytopenia with BM suppression is an uncommon hematological manifestation of active tuberculosis (91). This may be due to granulomatous inflammation and focal necrosis in the BM (92). Although not clearly defined, other mechanisms that may lead to pancytopenia in these patients include histiocytic hyperplasia, HSC maturation arrest, and hypersplenism (92, 93).

Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

During acute infections, the immune system regulates the expansion and differentiation of HSCs in an attempt to appropriately combat invasive pathogens. However, sustained signaling mechanisms may lead to chronic HSC exhaustion and BM suppression. Clinically, many microbial infections have been associated with BMFS; however, identifying patients who are susceptible to hematopoietic suppression remains impossible at present. Immune-mediated BMF following clearance of viral infections may be a common mechanism; however, further investigation regarding inflammatory-related genes, immune education, and tolerance is needed. For instance, regulatory T-cells, which maintain self-tolerance and prevent excessive immune activation, have also been found to suppress colony formation in vitro and HSC myeloid differentiation in vivo (94, 95). Notably, the numbers of regulatory T-cells are significantly diminished in patients with acquired AA (96). Specific regulatory T-cell changes following microbial infections in certain system compartments have not been investigated, but may now be detectable with the advent of new cellular subset population analyses (97).

How chronic infections may affect HSCs over time remains unknown as well. As this review highlights, the gut microbiome may have a direct role in normal hematopoiesis, as microbes and their metabolic products may have downstream consequences. As proposed, dysbiosis may trigger autoimmune effects via the enzymatic posttranslation modification of proteins and generation of neoantigens for unique T-cell responses (98). This model is quite well-suited for studying the basis for immune-mediated BMFS, particularly in patients with known microbial alterations like inflammatory bowel diseases. However, further research that characterizes the microflora patterns, whether by genomic or metabolic recognition, may have novel diagnostic and prognostic utility. Interventions targeting the suppression and removal of distinct microbial species may have a tremendous impact on human health and disease.

Author Contributions

JE and RK: literature search, wrote the manuscript, and designed Figure 1. SN wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and funds from the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. 2604419-00).

References

- 1.Nakao S. Guest editorial: advances in the management of acquired aplastic anemia. Int J Hematol (2013) 97:551–2. 10.1007/s12185-013-1325-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dezern AE, Brodsky RA. Clinical management of aplastic anemia. Expert Rev Hematol (2011) 4:221–30. 10.1586/ehm.11.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartung HD, Olson TS, Bessler M. Acquired aplastic anemia in children. Pediatr Clin North Am (2013) 60:1311–36. 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young NS. Current concepts in the pathophysiology and treatment of aplastic anemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program (2013) 2013:76–81. 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng Y, Katsanis E. The complex pathophysiology of acquired aplastic anaemia. Clin Exp Immunol (2015) 180:361–70. 10.1111/cei.12605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espinoza J, Takamatsu H, Lu X, Qi Z, Nakao S. Anti-moesin antibodies derived from patients with aplastic anemia stimulate monocytic cells to secrete TNF-alpha through an ERK1/2-dependent pathway. Int Immunol (2009) 21:913–23. 10.1093/intimm/dxp058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takamatsu H, Espinoza J, Lu X, Qi Z, Okawa K, Nakao S. Anti-moesin antibodies in the serum of patients with aplastic anemia stimulate peripheral blood mononuclear cells to secrete TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma. J Immunol (2009) 182:703–10. 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng X, Chuhjo T, Sugimori C, Kotani T, Lu X, Takami A, et al. Diazepam-binding inhibitor-related protein 1: a candidate autoantigen in acquired aplastic anemia patients harboring a minor population of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria-type cells. Blood (2004) 104:2425–31. 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogawa S. Clonal hematopoiesis in acquired aplastic anemia. Blood (2016) 28(3):337–47. 10.1182/blood-2016-01-636381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalayer E, Ffrench M, Cathébras P. Aplastic anemia as a feature of systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report and literature review. Rheumatol Int (2015) 35:1073–82. 10.1007/s00296-014-3162-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espinoza JL, Elbadry MI, Nakao S. An altered gut microbiota may trigger autoimmune-mediated acquired bone marrow failure syndromes. Clin Immunol (2016) 171:62–4. 10.1016/j.clim.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghavidel A. Ulcerative colitis associated with aplastic anemia; a case report. Middle East J Dig Dis (2013) 5:230–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Oliveira LR, Ferreira TC, Neves FF, Meneses AC. Aplastic anemia associated to systemic lupus erythematosus in an AIDS patient: a case report. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter (2013) 35:366–8. 10.5581/1516-8484.20130100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morinet F, Leruez-Ville M, Pillet S, Fichelson S. Concise review: anemia caused by viruses. Stem Cells (2011) 29:1656–60. 10.1002/stem.725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riether C, Schürch CM, Ochsenbein AF. Regulation of hematopoietic and leukemic stem cells by the immune system. Cell Death Differ (2015) 22:187–98. 10.1038/cdd.2014.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pietras EM, Warr MR, Passegué E. Cell cycle regulation in hematopoietic stem cells. J Cell Biol (2011) 195:709–20. 10.1083/jcb.201102131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldridge MT, King KY, Goodell MA. Inflammatory signals regulate hematopoietic stem cells. Trends Immunol (2011) 32:57–65. 10.1016/j.it.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scumpia PO, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Delano MJ, Weinstein JS, Cuenca AG, Al-Quran S, et al. Cutting edge: bacterial infection induces hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell expansion in the absence of TLR signaling. J Immunol (2010) 184:2247–51. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pascutti MF, Erkelens MN, Nolte MA. Impact of viral infections on hematopoiesis: from beneficial to detrimental effects on bone marrow output. Front Immunol (2016) 7:364. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirantes C, Passegué E, Pietras EM. Pro-inflammatory cytokines: emerging players regulating HSC function in normal and diseased hematopoiesis. Exp Cell Res (2014) 329:248–54. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Essers MA, Offner S, Blanco-Bose WE, Waibler Z, Kalinke U, Duchosal MA, et al. IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature (2009) 458:904–8. 10.1038/nature07815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato T, Onai N, Yoshihara H, Arai F, Suda T, Ohteki T. Interferon regulatory factor-2 protects quiescent hematopoietic stem cells from type I interferon-dependent exhaustion. Nat Med (2009) 15:696–700. 10.1038/nm.1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rezzoug F, Huang Y, Tanner MK, Wysoczynski M, Schanie CL, Chilton PM, et al. TNF-alpha is critical to facilitate hemopoietic stem cell engraftment and function. J Immunol (2008) 180:49–57. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schürch CM, Riether C, Ochsenbein AF. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells stimulate hematopoietic progenitors by promoting cytokine release from bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Cell Stem Cell (2014) 14:460–72. 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furusawa J, Mizoguchi I, Chiba Y, Hisada M, Kobayashi F, Yoshida H, et al. Promotion of expansion and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells by interleukin-27 into myeloid progenitors to control infection in emergency myelopoiesis. PLoS Pathog (2016) 12:e1005507. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Bruin AM, Demirel Ö, Hooibrink B, Brandts CH, Nolte MA. Interferon-γ impairs proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Blood (2013) 121:3578–85. 10.1182/blood-2012-05-432906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Bruin AM, Voermans C, Nolte MA. Impact of interferon-γ on hematopoiesis. Blood (2014) 124:2479–86. 10.1182/blood-2014-04-568451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodríguez JM, Murphy K, Stanton C, Ross RP, Kober OI, Juge N, et al. The composition of the gut microbiota throughout life, with an emphasis on early life. Microb Ecol Health Dis (2015) 26:26050. 10.3402/mehd.v26.26050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dollé L, Tran HQ, Etienne-Mesmin L, Chassaing B. Policing of gut microbiota by the adaptive immune system. BMC Med (2016) 14:27. 10.1186/s12916-016-0573-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bashan A, Gibson TE, Friedman J, Carey VJ, Weiss ST, Hohmann EL, et al. Universality of human microbial dynamics. Nature (2016) 534:259–62. 10.1038/nature18301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balmer ML, Schürch CM, Saito Y, Geuking MB, Li H, Cuenca M, et al. Microbiota-derived compounds drive steady-state granulopoiesis via MyD88/TICAM signaling. J Immunol (2014) 193:5273–83. 10.4049/jimmunol.1400762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taur Y, Jenq RR, Perales MA, Littmann ER, Morjaria S, Ling L, et al. The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood (2014) 124:1174–82. 10.1182/blood-2014-02-554725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khosravi A, Yáñez A, Price JG, Chow A, Merad M, Goodridge HS, et al. Gut microbiota promote hematopoiesis to control bacterial infection. Cell Host Microbe (2014) 15:374–81. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manzo VE, Bhatt AS. The human microbiome in hematopoiesis and hematologic disorders. Blood (2015) 126:311–8. 10.1182/blood-2015-04-574392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Yadava K, Sichelstiel AK, Sprenger N, Ngom-Bru C, et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med (2014) 20:159–66. 10.1038/nm.3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boiko JR, Borghesi L. Hematopoiesis sculpted by pathogens: toll-like receptors and inflammatory mediators directly activate stem cells. Cytokine (2012) 57:1–8. 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovtonyuk LV, Fritsch K, Feng X, Manz MG, Takizawa H. Inflamm-aging of hematopoiesis, hematopoietic stem cells, and the bone marrow microenvironment. Front Immunol (2016) 7:502. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takizawa H, Regoes RR, Boddupalli CS, Bonhoeffer S, Manz MG. Dynamic variation in cycling of hematopoietic stem cells in steady state and inflammation. J Exp Med (2011) 208:273–84. 10.1084/jem.20101643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, Tzameli I, Yin H, Flier JS. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest (2006) 116:3015–25. 10.1172/JCI28898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kell DB, Pretorius E. On the translocation of bacteria and their lipopolysaccharides between blood and peripheral locations in chronic, inflammatory diseases: the central roles of LPS and LPS-induced cell death. Integr Biol (Camb) (2015) 7:1339–77. 10.1039/c5ib00158g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barin JG, Tobias LD, Peterson DA. The microbiome and autoimmune disease: report from a Noel R. Rose Colloquium. Clin Immunol (2015) 159:183–8. 10.1016/j.clim.2015.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karczewski J, Poniedziałek B, Adamski Z, Rzymski P. The effects of the microbiota on the host immune system. Autoimmunity (2014) 47:494–504. 10.3109/08916934.2014.938322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Servant-Delmas A, Morinet F. Update of the human parvovirus B19 biology. Transfus Clin Biol (2016) 23:5–12. 10.1016/j.tracli.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Libregts SF, Nolte MA. Parallels between immune driven-hematopoiesis and T cell activation: 3 signals that relay inflammatory stress to the bone marrow. Exp Cell Res (2014) 329:239–47. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bathla L, Grant WJ, Mercer DF, Vargas LM, Gebhart CL, Langnas AN. Parvovirus associated fulminant hepatic failure and aplastic anemia treated successfully with liver and bone marrow transplantation. A report of two cases. Am J Transplant (2014) 14:2645–50. 10.1111/ajt.12857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rogo LD, Mokhtari-Azad T, Kabir MH, Rezaei F. Human parvovirus B19: a review. Acta Virol (2014) 58:199–213. 10.4149/av_2014_03_199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Florea AV, Ionescu DN, Melhem MF. Parvovirus B19 infection in the immunocompromised host. Arch Pathol Lab Med (2007) 131:799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolfromm A, Rodriguez C, Michel M, Habibi A, Audard V, Benayoun E, et al. Spectrum of adult parvovirus B19 infection according to the underlying predisposing condition and proposals for clinical practice. Br J Haematol (2015) 170:192–9. 10.1111/bjh.13421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kerr JR. Pathogenesis of human parvovirus B19 in rheumatic disease. Ann Rheum Dis (2000) 59:672–83. 10.1136/ard.59.9.672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thammasri K, Rauhamäki S, Wang L, Filippou A, Kivovich V, Marjomäki V, et al. Human parvovirus B19 induced apoptotic bodies contain altered self-antigens that are phagocytosed by antigen presenting cells. PLoS One (2013) 8:e67179. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Espinoza JL, Takami A, Trung LQ, Kato S, Nakao S. Resveratrol prevents EBV transformation and inhibits the outgrowth of EBV-immortalized human B cells. PLoS One (2012) 7:e51306. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Long HM, Taylor GS, Rickinson AB. Immune defence against EBV and EBV-associated disease. Curr Opin Immunol (2011) 23:258–64. 10.1016/j.coi.2010.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pender MP. CD8+ T-cell deficiency, Epstein-Barr virus infection, vitamin D deficiency, and steps to autoimmunity: a unifying hypothesis. Autoimmune Dis (2012) 2012:189096. 10.1155/2012/189096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yenicesu I, Yetgin S, Ozyürek E, Aslan D. Virus-associated immune thrombocytopenic purpura in childhood. Pediatr Hematol Oncol (2002) 19:433–7. 10.1080/08880010290097233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu LH, Fang JP, Weng WJ, Huang K, Guo HX, Liu Y, et al. Pure red cell aplasia associated with cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infection in seven cases of Chinese children. Hematology (2013) 18:56–9. 10.1179/1607845412Y.0000000044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gupta V, Pratap R, Kumar A, Saini I, Shukla J. Epidemiological features of aplastic anemia in Indian children. Indian J Pediatr (2013) 81(3):257–9. 10.1007/s12098-013-1242-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shadduck RK, Winkelstein A, Zeigler Z, Lichter J, Goldstein M, Michaels M, et al. Aplastic anemia following infectious mononucleosis: possible immune etiology. Exp Hematol (1979) 7:264–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan IIS, Mushtaq R, Onwuzurike N. EBV infection resulting in aplastic anemia: a case report and literature review. J Blood Disord Transfus (2013) 4:141. 10.4172/2155-9864.1000141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Santos Souza HF, da Silva Almeida B, Boscardin SB. Early dengue virus interactions: the role of dendritic cells during infection. Virus Res (2016) 223:88–98. 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark KB, Noisakran S, Onlamoon N, Hsiao HM, Roback J, Villinger F, et al. Multiploid CD61+ cells are the pre-dominant cell lineage infected during acute dengue virus infection in bone marrow. PLoS One (2012) 7:e52902. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noisakran S, Onlamoon N, Hsiao HM, Clark KB, Villinger F, Ansari AA, et al. Infection of bone marrow cells by dengue virus in vivo. Exp Hematol (2012) 40:250–9.e254. 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramzan M, PrakashYadav S, Sachdeva A. Post-dengue fever severe aplastic anemia: a rare association. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther (2012) 5:122–4. 10.5144/1658-3876.2012.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Albuquerque PL, Silva Júnior GB, Diógenes SS, Silva HF. Dengue and aplastic anemia – a rare association. Travel Med Infect Dis (2009) 7:118–20. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakao S, Lai CJ, Young NS. Dengue virus, a flavivirus, propagates in human bone marrow progenitors and hematopoietic cell lines. Blood (1989) 74:1235–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spain-Santana TA, Marglin S, Ennis FA, Rothman AL. MIP-1 alpha and MIP-1 beta induction by dengue virus. J Med Virol (2001) 65:324–30. 10.1002/jmv.2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Calvert JK, Helbig KJ, Dimasi D, Cockshell M, Beard MR, Pitson SM, et al. Dengue virus infection of primary endothelial cells induces innate immune responses, changes in endothelial cells function and is restricted by interferon-stimulated responses. J Interferon Cytokine Res (2015) 35:654–65. 10.1089/jir.2014.0195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clarke JN, Davies LK, Calvert JK, Gliddon BL, Al Shujari WH, Aloia AL, et al. Reduction in sphingosine kinase 1 influences the susceptibility to dengue virus infection by altering antiviral responses. J Gen Virol (2016) 97:95–109. 10.1099/jgv.0.000334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mangione JN, Huy NT, Lan NT, Mbanefo EC, Ha TT, Bao LQ, et al. The association of cytokines with severe dengue in children. Trop Med Health (2014) 42:137–44. 10.2149/tmh.2014-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hsu YL, Wang MY, Ho LJ, Lai JH. Dengue virus infection induces interferon-lambda1 to facilitate cell migration. Sci Rep (2016) 6:24530. 10.1038/srep24530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Donnelly RP, Kotenko SV. Interferon-lambda: a new addition to an old family. J Interferon Cytokine Res (2010) 30:555–64. 10.1089/jir.2010.0078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rauff B, Idrees M, Shah SA, Butt S, Butt AM, Ali L, et al. Hepatitis associated aplastic anemia: a review. Virol J (2011) 8:87. 10.1186/1743-422X-8-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gonzalez-Casas R, Garcia-Buey L, Jones EA, Gisbert JP, Moreno-Otero R. Systematic review: hepatitis-associated aplastic anaemia – a syndrome associated with abnormal immunological function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther (2009) 30:436–43. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Safadi R, Or R, Ilan Y, Naparstek E, Nagler A, Klein A, et al. Lack of known hepatitis virus in hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia and outcome after bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant (2001) 27:183–90. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang H, Tu M, Fu R, Wu Y, Liu H, Xing L, et al. The clinical and immune characteristics of patients with hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia in China. PLoS One (2014) 9:e98142. 10.1371/journal.pone.0098142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Khurana A, Dasanu CA. Hepatitis associated aplastic anemia: case report and discussion. Conn Med (2014) 78:493–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lu J, Basu A, Melenhorst JJ, Young NS, Brown KE. Analysis of T-cell repertoire in hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia. Blood (2004) 103:4588–93. 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mayer A, Podlech J, Kurz S, Steffens HP, Maiberger S, Thalmeier K, et al. Bone marrow failure by cytomegalovirus is associated with an in vivo deficiency in the expression of essential stromal hemopoietin genes. J Virol (1997) 71:4589–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Seifert ME, Brennan DC. Cytomegalovirus and anemia: not just for transplant anymore. J Am Soc Nephrol (2014) 25:1613–5. 10.1681/ASN.2014030249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lagadinou ED, Marangos M, Liga M, Panos G, Tzouvara E, Dimitroulia E, et al. Human herpesvirus 6-related pure red cell aplasia, secondary graft failure, and clinical severe immune suppression after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation successfully treated with foscarnet. Transpl Infect Dis (2010) 12:437–40. 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2010.00515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Isomura H, Yoshida M, Namba H, Fujiwara N, Ohuchi R, Uno F, et al. Suppressive effects of human herpesvirus-6 on thrombopoietin-inducible megakaryocytic colony formation in vitro. J Gen Virol (2000) 81:663–73. 10.1099/0022-1317-81-3-663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rezaee F, Gibson LF, Piktel D, Othumpangat S, Piedimonte G. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in human bone marrow stromal cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2011) 45:277–86. 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0121OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Balan A, Lucchini G, Schmidt S, Schneider A, Tramsen L, Kuçi S, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells in the antimicrobial host response of hematopoietic stem cell recipients with graft-versus-host disease – friends or foes? Leukemia (2014) 28:1941–8. 10.1038/leu.2014.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kolb-Mäurer A, Wilhelm M, Weissinger F, Bröcker EB, Goebel W. Interaction of human hematopoietic stem cells with bacterial pathogens. Blood (2002) 100:3703–9. 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim JM, Oh YK, Kim YJ, Youn J, Ahn MJ. Escherichia coli up-regulates proinflammatory cytokine expression in granulocyte/macrophage lineages of CD34 stem cells via p50 homodimeric NF-kappaB. Clin Exp Immunol (2004) 137:341–50. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02542.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Atif FA. Anaplasma marginale and Anaplasma phagocytophilum: rickettsiales pathogens of veterinary and public health significance. Parasitol Res (2015) 114:3941–57. 10.1007/s00436-015-4698-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pozdnyakova O, Dorfman DM. Human granulocytic anaplasmosis. Blood (2012) 120:4911. 10.1182/blood-2012-07-445817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ohashi N, Gaowa, Wuritu, Kawamori F, Wu D, Yoshikawa Y, et al. Human granulocytic anaplasmosis, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis (2013) 19:289–92. 10.3201/eid1902.120855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Johns JL, Macnamara KC, Walker NJ, Winslow GM, Borjesson DL. Infection with Anaplasma phagocytophilum induces multilineage alterations in hematopoietic progenitor cells and peripheral blood cells. Infect Immun (2009) 77:4070–80. 10.1128/IAI.00570-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bakken JS, Dumler JS. Human granulocytic anaplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am (2015) 29:341–55. 10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.MacNamara KC, Racine R, Chatterjee M, Borjesson D, Winslow GM. Diminished hematopoietic activity associated with alterations in innate and adaptive immunity in a mouse model of human monocytic ehrlichiosis. Infect Immun (2009) 77:4061–9. 10.1128/IAI.01550-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Singh KJ, Ahluwalia G, Sharma SK, Saxena R, Chaudhary VP, Anant M. Significance of haematological manifestations in patients with tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India (2001) 49(788):790–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Avasthi R, Mohanty D, Chaudhary SC, Mishra K. Disseminated tuberculosis: interesting hematological observations. J Assoc Physicians India (2010) 58:243–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chandni R, Rajan G, Udayabhaskaran V. Extra pulmonary tuberculosis presenting as fever with massive splenomegaly and pancytopenia. IDCases (2016) 4:20–2. 10.1016/j.idcr.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zeng D, Hoffmann P, Lan F, Huie P, Higgins J, Strober S. Unique patterns of surface receptors, cytokine secretion, and immune functions distinguish T cells in the bone marrow from those in the periphery: impact on allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood (2002) 99:1449–57. 10.1182/blood.V99.4.1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Urbieta M, Barao I, Jones M, Jurecic R, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Blazar BR, et al. Hematopoietic progenitor cell regulation by CD4+CD25+ T cells. Blood (2010) 115:4934–43. 10.1182/blood-2009-04-218826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dao AT, Yamazaki H, Takamatsu H, Sugimori C, Katagiri T, Maruyama H, et al. Cyclosporine restores hematopoietic function by compensating for decreased Tregs in patients with pure red cell aplasia and acquired aplastic anemia. Ann Hematol (2016) 95:771–81. 10.1007/s00277-016-2629-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bendall SC, Simonds EF, Qiu P, Amir el AD, Krutzik PO, Finck R, et al. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science (2011) 332:687–96. 10.1126/science.1198704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lerner A, Aminov R, Matthias T. Dysbiosis may trigger autoimmune diseases via inappropriate post-translational modification of host proteins. Front Microbiol (2016) 7:84. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]