Abstract

Bacteriophage φ29 protein p6 is a viral architectural protein, which binds along the whole linear φ29 DNA in vivo and is involved in initiation of DNA replication and transcription control. Protein p1 is a membrane-associated viral protein, proposed to attach the viral genome to the cell membrane. Protein p17 is involved in pulling φ29 DNA into the cell during the injection process. We have used chromatin immunoprecipitation and real-time PCR to analyze in vivo p6 binding to DNA in cells infected with φ29 sus1 or sus17 mutants; in both cases p6 binding is significantly decreased all along φ29 DNA. φ29 DNA is topologically constrained in vivo, and p6 binding is highly increased in the presence of novobiocin, a gyrase inhibitor that produces a loss of DNA negative superhelicity. Here we show that, in cells infected with φ29 sus1 or sus17 mutants, the increase of p6 binding by novobiocin is even higher than in cells containing p1 and p17, alleviating the p6 binding deficiency. Therefore, proteins p1 and p17 could be required to restrain the proper topology of φ29 DNA, which would explain the impaired DNA replication observed in cells infected with sus1 or sus17 mutants.

Prokaryotic genomes are organized and compacted by architectural (histonelike) proteins such as Escherichia coli HU, IHF, Fis, Dps, or H-NS (2, 10) or Bacillus subtilis HBsu (21), LrpC (29), and L24 (12). These proteins not only reduce the DNA length to fit it into the cell but also play a central role in essential DNA transactions such as replication (18), transcription (9), recombination (26), or segregation (17). B. subtilis phage φ29 linear DNA, 19,285 bp long, replicates by a protein-priming mechanism in which a free molecule of the terminal protein (TP) acts as a primer, remaining covalently bound to the 5′ DNA ends. This TP-DNA is organized by p6, a small and very abundant (1) viral architectural protein that binds all along the φ29 DNA in vivo (15). Protein p6 has a pleiotropic effect. In vitro, p6 binding to the replication origins at both φ29 DNA ends activates initiation of DNA replication (13, 27); in agreement with these results, in vivo DNA replication is prevented after infection with a sus6 mutant (8, 25). Protein p6 also represses the early C2 promoter, at the right DNA end (3, 7, 30), and, together with viral protein p4, represses early promoters A2b-A2c and activates late promoter A3 at the central region of transcriptional control (11).

In vitro protein p6 forms a nucleoprotein complex in which the DNA is wrapped around a multimeric protein core, forming a right-handed toroidal superhelix (28). In agreement with this, protein p6 binding to DNA is impaired by negative superhelicity, which could explain its in vivo specificity for noncovalently closed viral TP-DNA with respect to bacterial DNA (15). Although protein p6 does not recognize a specific sequence, it binds preferentially to both DNA ends due to the presence of sequences prone to bend following the path of the DNA in the nucleoprotein complex (14, 27). This preferential p6 binding may be essential for activation of initiation of φ29 DNA replication.

Phage φ29 protein p1 is a membrane-associated protein (5). It is able to form large protofilament sheets in vitro, which could form a scaffold to organize φ29 TP-DNA replication in vivo, in agreement with the defective-replication phenotype observed for a sus1 mutant (6). No evidence of a direct interaction between p1 and DNA has been obtained; however, p1 is able to interact directly with primer TP (4). Therefore, a model was proposed in which φ29 DNA is attached to a membrane-associated p1-based viral structure through a direct interaction between p1 and the DNA-linked TP (4). This structure could account for the topological constraint of φ29 DNA and therefore influence p6 binding. On the other hand, p17, a protein synthesized from promoter C2, at the right DNA end, is involved in the internalization of the left half of the φ29 genome during the injection process (16). A direct or indirect binding to DNA could be inferred from the role of protein p17 in injection, and thus, protein p17 could also be involved in the topological restriction of the viral genome.

In this work, using cross-linked chromatin immunoprecipitation (X-ChIP) and real-time PCR, we demonstrate that both p1 and p17 are required for an efficient p6 binding to φ29 DNA in vivo. The impaired p6 binding in their absence is observed not only at the DNA ends but also all along the viral genome. In fact, treatment with novobiocin, which reduces the level of negative DNA supercoiling, compensates for the defective p6 binding of both mutants. Therefore, both p1 and p17 could provide the viral genome with the proper topology for p6 binding and viral DNA replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, plasmids, and phages.

B. subtilis strain 110NA (trpC2 spoOA3 Su−) (22) and the novobiocin-resistant strain (gyrB1 sacA321) were used as hosts. Infections were carried out with phage φ29 mutants sus14(1242), a delayed-lysis mutant with an otherwise wild-type phenotype (20); sus1(629) (24); and sus17(112) (22). Cells were grown in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 5 mM MgSO4 and 0.8 μg of phleomycin (Cayla S.A.R.L.)/ml.

DNAs and oligonucleotides.

Proteinase K-digested φ29 DNA was obtained as described previously (19). The sequences of the oligonucleotides used for PCR (Isogen) of the different DNA regions were as follows: region L (positions 1 to 259 of φ29 DNA), 5′-AAAGTAAGCCCCCACCCTCACATG and 5′-GCCCACATACTTTGTTGATTGG; region 5.1 (4895 to 5257), 5′-GATTTCTCTCTGCATCATTTTTGC and 5′-CAAAATATCTTCGTGTTCTTCTGG; region 9.7 (9507 to 9820), 5′-CTGACAACATCGGAAATTACAGCG and 5′-TTGTTGTAAACGTCTCTCTGACCC; region 11.7 (11567 to 11778), 5′-GGATTCTCAATGACGGGTTAGA and 5′-CACATACACAGGAAAACCAGACTC; region R (18988 to 19285), 5′-AAAGTAGGGTACAGCGACAACATAC and 5′-AAATAGATTTTCTTTCTTGGCTAC.

Cross-linking, immunoprecipitation, and DNA amplification.

Bacteria were grown at 30°C up to 108 cells/ml and infected at a multiplicity of 10 with φ29 mutant sus1(629) or a multiplicity of 3 with mutant sus17(112). As controls, cells were infected with sus14(1242) under the same conditions. Where indicated, chloramphenicol (Sigma) and novobiocin (Sigma) were added. X-ChIP was performed essentially as described elsewhere (16). Briefly, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde (Calbiochem) for 5 min and lysed, and DNA was sheared to an average size of 750 bp by sonication. Samples were divided into three aliquots, one for total DNA analysis and the other two for immunoprecipitation with either anti-p6 or preimmune serum. The DNA samples were purified and analyzed by real-time PCR in a Light Cycler instrument with the use of a Light Cycler-FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I hot-start reaction mix (Roche). Although the amplified sequences are ∼300 bp in average, they are representative of a much wider region, as the average size of the DNA fragments that contain these sequences is 750 bp. The data obtained for each region were interpolated to a standard curve constructed with purified, full-length, φ29 DNA. The results were expressed as picograms of φ29 DNA per milliliter of culture. Binding values are expressed as immunoprecipitation coefficient (IC): [(anti-p6 − preimmune serum)/total DNA sample] × 106.

The amplification conditions included a preheating step of 20 min at 95°C to activate the polymerase, followed by 30 cycles comprising a denaturation step of 15 s at 95°C for all regions; a hybridization step of 5 s at 53°C for regions L and 11.7, 5 s at 50°C for R, 10 s at 51°C for 9.7, and 10 s at 48°C for 5.1; and an elongation step at 72°C lasting 15 s for L and 11.7, 40 s for R, 30 s for 9.7, and 60 s for 5.1. Finally, a melting analysis was performed by continuous fluorescence measurement from 65 to 95°C, to check that a single product was amplified.

DNA replication.

B. subtilis cells were grown and infected as described above. At the times indicated, 1-ml aliquots were taken and cells were sedimented, washed, and lysed as described above. DNA was sonicated and extracted by phenolization. The amount of DNA from a given sequence was quantified by real-time PCR, according to the protocol described above.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were grown and infected as described above. At the time indicated, 1.5-ml aliquots were transferred to an ice-cold tube, concentrated 7.5-fold in loading buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 30% glycerol), and disrupted by sonication. Samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 15% polyacrylamide gel, and protein p6 was transferred using a Mini Trans-Blot apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 100 mA and 4°C for 60 min. Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore) were probed with 1:2,000-diluted anti-p6 polyclonal antibodies for 70 min. Then, membranes were washed twice and incubated with 1:4,000-diluted anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies for 70 min, and the immune complexes were detected by ECL detection reagents (Amersham). Films were scanned, and bands were subjected to densitometry using ImageQuant software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Protein p1 is required for efficient p6 binding to φ29 DNA.

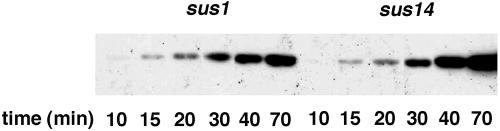

The effect of protein p1 on p6 binding to DNA was tested in φ29 sus1(629)-infected cells, taking as control sus14(1242)-infected cells. Phage sus14(1242) lacks a functional holin, and therefore it is convenient for studies at late infection times without the risk of cell lysis. Otherwise, it has a wild-type phenotype. Figure 1 shows a genetic map of the φ29 genome indicating the regions analyzed for protein p6 binding; L and R correspond to the left and right genome ends, respectively, while the internal regions 5.1, 9.7, and 11.7 are named according to their coordinates relative to the left DNA end. Since binding measurements have to be performed under conditions of equivalent protein concentration, we studied the kinetics of protein p6 synthesis in cells infected with mutant sus14(1242) or sus1(629). Figure 2 shows that the amount of p6 at 15 and 20 min postinfection is similar in sus1(629)- and sus14(1242)-infected cells, being only slightly lower for sus1(629)- than for sus14(1242)-infected cells after 30 min. At later times the difference increases, but this can be explained by the impaired DNA replication after sus1(629) infection as described below (see Fig. 3).

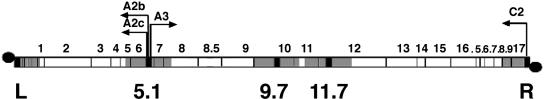

FIG. 1.

Location of the φ29 DNA regions analyzed for protein p6 binding in the genetic and transcription map of the 19.3-kb linear φ29 DNA. The sequences used for PCR amplification are shown in black, and the regions studied for protein p6 binding, shown in gray, were named L and R (left and right ends, respectively), and 5.1, 9.7, and 11.7, according to their coordinates from the left DNA end. Genes (1 to 17; .5 to .9 stand for genes 16.5 to 16.9), terminal protein (black circles), and main promoters (arrows) are indicated.

FIG. 2.

Protein p6 synthesis in φ29 sus1(629)- and sus14(1242)-infected cells. The amount of protein p6 at the indicated times postinfection was analyzed by Western blotting.

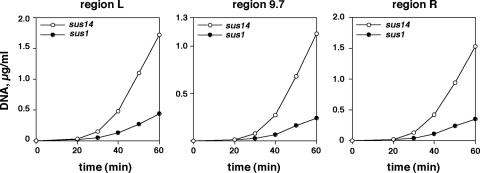

FIG. 3.

Viral DNA synthesis in φ29 sus1(629)- and sus14(1242)-infected cells. Cells were infected with sus1(629) or sus14(1242) mutant, under the same conditions used in the experiments represented in Table 1; at the indicated times the amount of DNA from the terminal (L and R) and central (9.7) regions shown in Fig. 1 was measured by real-time PCR. Data are expressed as micrograms of full-length DNA per milliliter of culture.

Protein p6 binding was measured by X-ChIP and real time-PCR, 15 min after infection with sus1(629) or sus14(1242), which ensured comparable amounts of both φ29 DNA and protein p6. Table 1 shows p6 binding, expressed as IC (see Materials and Methods), to φ29 DNA regions (Fig. 1). Protein p6 binding is much lower in sus1(629)- than in sus14(1242)-infected cells. The ICs are 5.7-, 2.6-, 3.9-, 4.1-, and 4.2-fold lower for regions L, 5.1, 9.7, 11.7, and R, respectively. These results indicate that protein p6 binding along most, if not all, φ29 DNA is impaired in a mutant lacking a functional p1 protein.

TABLE 1.

Protein p6 binding, expressed as IC, to φ29 DNA regions (L, 5.1, 9.7, 11.7, and R) in the absence or presence of novobiocin (Nov) and IC ratios with novobiocin/without novobiocin in sus1- and sus14-infected cells

| Region | IC

|

IC +Nov/−Nov

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − Nov

|

+ Nov

|

|||||

| sus1 | sus14 | sus1 | sus14 | sus1 | sus14 | |

| L | 174 | 984 | 5,319 | 14,929 | 30.6 | 15.2 |

| 5.1 | 65 | 172 | 303 | 543 | 4.7 | 3.2 |

| 9.7 | 58 | 224 | 1,983 | 4,090 | 34.2 | 18.3 |

| 11.7 | 63 | 261 | 1,545 | 2,559 | 24.5 | 9.8 |

| R | 181 | 762 | 4,595 | 9,505 | 25.4 | 12.5 |

Protein p1 could be involved in the topological restriction of the φ29 genome.

A model has been proposed in which the viral genome is attached to a p1-based membrane-associated structure (4). Furthermore, it was shown that protein p6 binding to DNA was strongly dependent on DNA topology, being impaired by negative supercoiling. In vitro p6 binding assays to plasmid DNA with different degrees of superhelicity showed that p6 binding was inversely proportional to negative supercoiling, being highest for the linearized, unrestrained plasmid (15). This suggests that the impaired p6 binding in cells infected with φ29 sus1(629) could be due to an improper topology of φ29 TP-DNA. To determine if protein p1 has any effect on the topology of the φ29 genome, we studied the effect of novobiocin on p6 binding to φ29 DNA in sus1(629)- and sus14(1242)-infected cells. Novobiocin, a gyrase inhibitor, reduces DNA negative superhelicity in vivo (15, 23) and increases p6 binding to φ29 DNA by at least 1 order of magnitude (14). Therefore, cells were treated with 500 μg of novobiocin/ml and 34 μg of chloramphenicol/ml 15 min after infection, and cross-linking was performed 10 min later. Table 1 shows that, as expected, p6 overall binding increases with respect to the untreated samples, but this increase is about twofold higher in sus1(629)- than in sus14(1242)-infected cells. Therefore, novobiocin is able to partially compensate for the p6 binding defect after sus1(629) infection. The possibility that the effect of novobiocin on p6 binding is due not to changes of supercoiling but to the inhibition of an enzyme other than gyrase has been ruled out through the use of a B. subtilis gyrB mutant, insensitive to novobiocin. In this case, novobiocin produced no increase of p6 binding (data not shown), at odds with the possibility that the observed effect is due to a gyrase-independent mechanism.

Since protein p1 has been proposed to form a membrane-associated structure that anchors φ29 TP-DNA (4), our results are compatible with a model in which, in the absence of p1, φ29 DNA would have an increased negative superhelicity that would impair p6 binding. This model would involve not a release of φ29 TP-DNA from the membrane but rather a direct interaction of the DNA-linked TP with the membrane. In fact, a significant percentage of free TP was found in membrane fractions of infected cells (5). This strongly suggests that in the absence of p1 φ29 TP-DNA is able to bind the membrane by itself.

Although the possibility that protein p1 loads p6 directly onto DNA cannot be ruled out, there is no evidence of protein p1 interaction with p6 and/or DNA. The differential effect of novobiocin in sus1(629)- and sus14(1242)-infected cells, although not conclusive, supports the supercoiling hypothesis as the most likely explanation of our results.

Protein p1 is required for efficient initiation of φ29 DNA replication.

From the above results it is suggested that protein p1 would provide φ29 TP-DNA with the topology adequate to allow an optimal p6 binding for replication, transcription control, and global genome organization. In fact, DNA replication is impaired in φ29 sus1(629)-infected cells (6). We have used real-time PCR to study the replication of φ29 sus1(629) TP-DNA, quantifying accurately the kinetics of DNA synthesis of φ29 DNA regions located at the ends (L and R) and at the center (9.7) of the genome (Fig. 1). Figure 3 shows a decreased replication rate (lower slope of the replication curves) rather than a significant delay in the onset of replication with respect to sus14(1242) infection.

φ29 DNA replicates by a protein-priming mechanism, with the replication origins at both DNA ends. Two replication forks travel from the ends towards the center of the molecule. In sus14(1242)-infected cells, 20 min postinfection and just after the onset of DNA replication, the L/9.7 and R/9.7 ratios are 2.01 and 1.67, respectively. In sus1(629)-infected cells, the values are 1.86 and 1.57 at the same infection time, indicating that there is no impairment in elongation; otherwise, the ratios would be higher than in sus14(1242)-infected cells. Therefore, these results suggest that protein p1 is required for efficient initiation of DNA replication. The replication-defective phenotype of φ29 sus1(629) could be explained, at least to a great extent, by the impaired binding of p6 to φ29 DNA replication origins.

Protein p17 is required for efficient p6 binding to φ29 DNA.

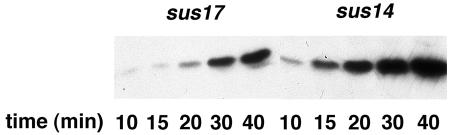

The linear φ29 TP-DNA penetrates into the cell with a right-left polarity, in a two-step process. In the first step ∼65% of the genome is pushed into the cell by the pressure built inside the viral capsid. In the second step at least one of the early proteins, p17, participates in a molecular motor that pulls the remaining DNA inside the cell (16). This direct or indirect interaction of p17 with φ29 TP-DNA in vivo could affect protein p6 binding. Therefore, we have measured protein p6 binding to φ29 DNA in φ29 sus17(112)-infected cells by X-ChIP and real-time PCR. The delayed-injection phenotype of this mutant is reflected in the synthesis of protein p6. The Western blot in Fig. 4 shows that a significant amount of protein p6 is not detected until 20 min postinfection in sus17(112)-infected cells, while a similar amount of p6 is found 10 min earlier after sus14(1242) infection. Therefore, we cross-linked cells 10 [sus14(1242)] or 20 [sus17(112)] min after infection, to achieve similar amounts of protein p6 in both infections; in addition, there is only input DNA at these infection times (Fig. 5). Table 2 shows that p6 binding to the φ29 DNA regions shown in Fig. 1 is lower in sus17(112)-infected cells than in sus14(1242)-infected cells: 3.9-, 3.0-, 2.9-, and 1.9-fold for regions L, 9.7, 11.7, and R, respectively. In the case of region L, the difference could be slightly overestimated, as the DNA injection process is probably not completed in sus17(112)-infected cells at this time. In fact, binding to L is lower than that to R, whereas we would expect a similar, if not higher, binding, as observed in sus14(1242)-infected cells. Binding to region 5.1, which has a particularly low intrinsic affinity for p6 (14), was undetectable for both mutants due to the low amount of DNA and p6 under our experimental conditions.

FIG. 4.

Protein p6 synthesis in φ29 sus17(112)- and sus14(1242)-infected cells. The amount of protein p6 in sus17(112)- and sus14(1242)-infected cells at the indicated times postinfection was analyzed by Western blotting.

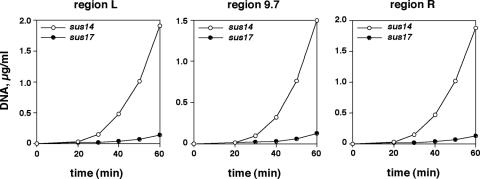

FIG. 5.

Viral DNA synthesis in φ29 sus17(112)- and sus14(1242)-infected cells. The amount of φ29 DNA at the indicated times after infection with mutant sus17(112) or sus14(1242) was measured by real-time PCR in the terminal (L and R) and central (9.7) regions shown in Fig. 1. Data are expressed as micrograms of full-length DNA per milliliter of culture.

TABLE 2.

Protein p6 binding, expressed as IC, to φ29 DNA regions (L, 5.1, 9.7, 11.7, and R) in the absence or presence of novobiocin (Nov) and IC ratios with novobiocin/without novobiocin in sus17- and sus14-infected cells at early infection times

| Region | IC

|

IC +Nov/−Nov

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − Nov

|

+ Nov

|

|||||

| sus17 | sus14 | sus17 | sus14 | sus17 | sus14 | |

| L | 56 | 218 | 361 | 423 | 6.4 | 1.9 |

| 5.1 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 24 | NCa | NC |

| 9.7 | 27 | 80 | 299 | 150 | 11.1 | 1.9 |

| 11.7 | 36 | 103 | 190 | 126 | 5.3 | 1.2 |

| R | 100 | 194 | 631 | 455 | 6.3 | 2.3 |

NC, not calculated.

The involvement of protein p17 in the DNA injection process (16) implies that it performs an early function. Furthermore, the effect of p17 would be diminished late in the infection since gene 17 early transcription is switched off by protein p6 (3, 30). Thus, we studied p6 binding at 35 [sus14(1242)] or 60 [sus17(112)] min postinfection, conditions that ensure similar amounts of protein p6 (data not shown) and DNA (Fig. 5). Table 3 shows that, in fact, the differences in p6 binding to all the regions are very much reduced, especially at the genome ends.

TABLE 3.

Protein p6 binding, expressed as IC, to φ29 DNA regions (L, 5.1, 9.7, 11.7, and R) in the absence or presence of novobiocin (Nov) and IC ratios with novobiocin/without novobiocin in sus17- and sus14-infected cells at late infection times

| Region | IC

|

IC +Nov/−Nov

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − Nov

|

+ Nov

|

|||||

| sus17 | sus14 | sus17 | sus14 | sus17 | sus14 | |

| L | 541 | 524 | 63,103 | 74,026 | 116.6 | 141.3 |

| 5.1 | 57 | 75 | 3,957 | 3,645 | 69.4 | 48.6 |

| 9.7 | 100 | 165 | 13,311 | 14,917 | 133.1 | 90.4 |

| 11.7 | 101 | 141 | 9,517 | 10,983 | 94.2 | 77.9 |

| R | 496 | 509 | 39,579 | 50,560 | 79.8 | 99.3 |

Protein p6 DNA binding impairment after sus17(112) infection is overcome by a reduced negative superhelicity.

The p6 binding impairment observed in sus17(112)-infected cells could be due to an improper φ29 DNA topology, namely, an increased negative supercoiling as observed in φ29 sus1(629) mutant infection. To test this hypothesis, we studied p6 binding to φ29 DNA in sus17(112)-infected cells treated with novobiocin by addition of 500 μg of novobiocin/ml and 34 μg of chloramphenicol/ml at 10 [sus14(1242)-infected cells] or 20 [sus17(112)-infected cells] min postinfection and performance of cross-linking 10 min later. Table 2 shows that at early infection times the p6 binding increase in the presence of novobiocin is relatively modest due to the low p6 concentration (Fig. 4); however, this increase is 4.6-fold higher on average than in sus14(1242)-infected cells. As a result, the IC values not only reach those of sus14(1242)-infected cells but are even higher except for region L.

We also studied the effect of novobiocin at late infection times. For this, we added novobiocin and chloramphenicol at 35 [sus14(1242)-infected cells] or 60 [sus17(112)-infected cells] min postinfection. Table 3 shows that the p6 binding increase by novobiocin is much greater for both mutants at later infection times, as the p6 and DNA concentrations are higher. However, the overall binding increase is the same for sus17(112)- and sus14(1242)-infected cells.

Taken together, these results suggest that protein p17 affects φ29 TP-DNA topology and that the viral genome has a lower negative superhelicity in its absence. However, the effect of p17 on p6 binding to DNA is transient, occurring only at early infection times.

φ29 DNA replication is severely impaired in sus17(112)-infected cells.

A topological change in φ29 DNA in sus17(112)-infected cells could have a profound effect on viral genome replication. Thus, we have directly measured φ29 DNA synthesis of regions L, R, and 9.7 (Fig. 1), by real-time PCR in sus17(112)- and sus14(1242)-infected cells. Figure 5 shows that replication of the three regions in sus17(112) infection is severely impaired with respect to infection with sus14(1242). The ∼20-min delay in the replication onset can be explained by the delayed injection of the left half of φ29 DNA (16), which codes for most of the proteins required for replication. However, the replication rate is greatly decreased, so that the average amount of DNA synthesized by the sus17(112) mutant is 13.5-fold lower than that by sus14(1242) at 60 min postinfection. As observed with sus1(629) (see above), replication of the central region 9.7 is impaired to the same extent as that of the φ29 DNA ends, L and R, which strongly suggests that elongation is not specifically affected. Therefore, in the sus17(112) mutant, and in agreement with the defective p6 binding to the origins, DNA replication would be affected at the initiation step.

In summary, protein p17 increases binding of protein p6 to φ29 DNA. The facts that the effect of p17 on p6 binding is not specific to the replication origins but general to the entire φ29 DNA and that it can be mimicked by novobiocin strongly suggest that p17 could participate in the maintenance of φ29 DNA topology, which could account for the defective DNA replication exhibited by mutant sus17(112). Protein p17 is an essential component of the injection machinery that pulls the second half of φ29 DNA inside the cell. Therefore, it is conceivable that, following completion of injection, TP-DNA remains bound to p17, either directly or indirectly, until protein p1, which would form the scaffold that anchors φ29 DNA to the membrane, is synthesized. This injection machinery could topologically constrain the viral DNA, so that the normal DNA topology could be altered in the absence of p17.

Conclusions.

We conclude that (i) protein p6 binding to φ29 DNA is impaired in cells infected with mutants sus1(629) and sus17(112); (ii) this impaired binding could be due to an altered topology of the viral DNA, as novobiocin compensates for the binding defect of the mutants; and (iii) the altered topology of the DNA after infection with sus1(629) and sus17(112) mutants could explain their impaired DNA replication.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to L. Villar for purified φ29 DNA.

This work was supported by research grants 2R01 GM27242-24 from the National Institutes of Health and BMC2002-03818 from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología and by an institutional grant from the Fundación Ramón Areces to the Centro de Biología Molecular “Severo Ochoa.” V.G.-H. is the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship of the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid, and M.A. is a predoctoral fellow of the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abril, A. M., M. Salas, J. M. Andreu, J. M. Hermoso, and G. Rivas. 1997. Phage φ29 protein p6 is in a monomer-dimer equilibrium that shifts to higher association states at the millimolar concentrations found in vivo. Biochemistry 36:11901-11908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azam, T. A., and A. Ishihama. 1999. Twelve species of the nucleoid-associated protein from Escherichia coli. Sequence recognition specificity and DNA binding affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33105-33113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barthelemy, I., R. P. Mellado, and M. Salas. 1989. In vitro transcription of bacteriophage Φ29 DNA: inhibition of early promoters by the viral replication protein p6. J. Virol. 63:460-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bravo, A., B. Illana, and M. Salas. 2000. Compartmentalization of phage φ29 DNA replication: interaction between the primer terminal protein and the membrane-associated protein p1. EMBO J. 19:5575-5584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bravo, A., and M. Salas. 1997. Initiation of bacteriophage φ29 DNA replication in vivo: assembly of a membrane-associated multiprotein complex. J. Mol. Biol. 269:102-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bravo, A., and M. Salas. 1998. Polymerization of bacteriophage φ29 replication protein p1 into protofilament sheets. EMBO J. 17:6096-6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camacho, A., and M. Salas. 2001. Repression of bacteriophage φ29 early promoter C2 by viral protein p6 is due to impairment of closed complex. J. Biol. Chem. 276:28927-28932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrascosa, J. L., A. Camacho, F. Moreno, F. Jiménez, R. P. Mellado, E. Viñuela, and M. Salas. 1976. Bacillus subtilis phage φ29: characterization of gene products and functions. Eur. J. Biochem. 66:229-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorman, C. J., and P. Deighan. 2003. Regulation of gene expression by histone-like proteins in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13:179-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drlica, K., and J. Rouvière-Yaniv. 1987. Histone-like proteins of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 51:301-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elías-Arnanz, M., and M. Salas. 1999. Functional interactions between a phage histone-like protein and a transcriptional factor in regulation of φ29 early-late transcriptional switch. Genes Dev. 13:2502-2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Exley, R., M. Zouine, J. J. Pernelle, C. Beloin, F. Le Hégarat, and A. M. Deneubourg. 2001. A possible role for L24 of Bacillus subtilis in nucleoid organization and segregation. Biochimie 83:269-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freire, R., M. Salas, and J. M. Hermoso. 1994. A new protein domain for binding to DNA through the minor groove. EMBO J. 13:4353-4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.González-Huici, V., M. Alcorlo, M. Salas, and J. M. Hermoso. 2004. Binding of phage φ29 architectural protein p6 to the viral genome. Evidence for topological restriction of the phage linear DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:3493-3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.González-Huici, V., M. Salas, and J. M. Hermoso. 2004. Genome wide, supercoiling-dependent, in vivo binding of a viral protein involved in DNA replication and transcriptional control. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:2306-2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.González-Huici, V., M. Salas, and J. M. Hermoso. 2004. The push-pull mechanism of bacteriophage φ29 DNA injection. Mol. Microbiol. 52:529-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon, G. S., and A. Wright. 2000. DNA segregation in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:681-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang, D. S., and A. Kornberg. 1992. Opening of the replication origin of Escherichia coli by DnaA protein with protein HU or IHF. J. Biol. Chem. 267:23083-23086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inciarte, M. R., J. M. Lázaro, M. Salas, and E. Viñuela. 1976. Physical map of bacteriophage φ29 DNA. Virology 74:314-323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiménez, F., A. Camacho, J. De La Torre, E. Viñuela, and M. Salas. 1977. Assembly of Bacillus subtilis phage φ29. 2. Mutants in the cistrons coding for the non-structural proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 73:57-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Köhler, P., and M. A. Marahiel. 1997. Association of the histone-like protein HBsu with the nucleoid of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 179:2060-2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno, F., A. Camacho, E. Viñuela, and M. Salas. 1974. Supressor-sensitive mutants and genetic map of Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage φ29. Virology 62:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osburne, M. S., S. M. Zavodny, and G. A. Peterson. 1988. Drug-induced relaxation of supercoiled plasmid DNA in Bacillus subtilis and induction of the SOS response. J. Bacteriol. 170:442-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reilly, B. E., V. M. Zeece, and D. L. Anderson. 1973. Genetic study of suppressor-sensitive mutants of the Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage φ29. J. Virol. 11:756-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schachtele, C. F., B. E. Reilly, C. V. De Sain, M. O. Whittington, and D. L. Anderson. 1973. Selective replication of bacteriophage φ29 deoxyribonucleic acid in 6-(p-hydroxyphenylazo)-uracil-treated Bacillus subtilis. J. Virol. 11:153-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segall, A. M., S. D. Goodman, and H. A. Nash. 1994. Architectural elements in nucleoprotein complexes: interchangeability of specific and non-specific DNA binding proteins. EMBO J. 13:4536-4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serrano, M., J. Gutiérrez, I. Prieto, J. M. Hermoso, and M. Salas. 1989. Signals at the bacteriophage φ29 DNA replication origins required for protein p6 binding and activity. EMBO J. 8:1879-1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serrano, M., C. Gutiérrez, M. Salas, and J. M. Hermoso. 1993. Superhelical path of the DNA in the nucleoprotein complex that activates the initiation of phage φ29 DNA replication. J. Mol. Biol. 230:248-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tapias, A., G. López, and S. Ayora. 2000. Bacillus subtilis LrpC is a sequence-independent DNA-binding and DNA-bending protein which bridges DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:552-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whiteley, H. R., W. D. Ramey, G. B. Spiegelman, and R. D. Holder. 1986. Modulation of in vivo and in vitro transcription of bacteriophage φ29 early genes. Virology 155:392-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]