Abstract

Life on Earth evolved in the presence of gravity, and thus it is of interest from the perspective of space exploration to determine if diminished gravity affects biological processes. Cultivation of Escherichia coli under low-shear simulated microgravity (SMG) conditions resulted in enhanced stress resistance in both exponential- and stationary-phase cells, making the latter superresistant. Given that microgravity of space and SMG also compromise human immune response, this phenomenon constitutes a potential threat to astronauts. As low-shear environments are encountered by pathogens on Earth as well, SMG-conferred resistance is also relevant to controlling infectious disease on this planet. The SMG effect resembles the general stress response on Earth, which makes bacteria resistant to multiple stresses; this response is σs dependent, irrespective of the growth phase. However, SMG-induced increased resistance was dependent on σs only in stationary phase, being independent of this sigma factor in exponential phase. σs concentration was some 30% lower in exponential-phase SMG cells than in normal gravity cells but was twofold higher in stationary-phase SMG cells. While SMG affected σs synthesis at all levels of control, the main reasons for the differential effect of this gravity condition on σs levels were that it rendered the sigma protein less stable in exponential phase and increased rpoS mRNA translational efficiency. Since σs regulatory processes are influenced by mRNA and protein-folding patterns, the data suggest that SMG may affect these configurations.

Space flights, space stations, and eventual colonization of space—the core missions of National Aeronautics and Space Administration—entail exposure of humans and microbes to diminished-gravity environments. Since gravity is a permanent feature on Earth and life on this planet evolved in its presence, diminished gravity might affect biological processes. In fact, detrimental effects of space flight on the immune system of astronauts are well documented (5, 20, 33). Studies involving Earth-based systems to simulate microgravity have shown that many factors may contribute to a diminished immune response. Examples include altered proportion of circulating lymphocytes, reduction in peripheral blood mononuclear and erythroid cells, and defective or depressed dendritic T-cell activity (2, 3, 13, 27, 37).

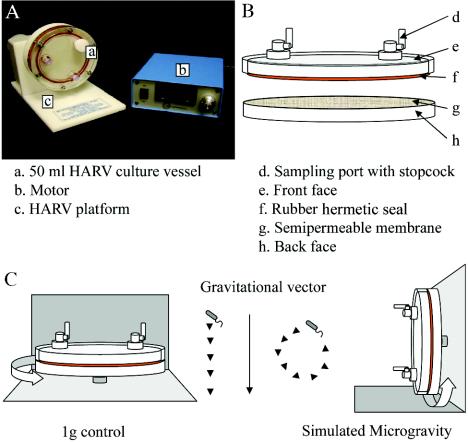

A commonly used Earth-based system to generate a low-shear simulated microgravity (SMG) environment is the high-aspect-ratio vessel (HARV) bioreactor (Synthecon, Inc., Houston, Tex.)(Fig. 1). In the vessel rotated about a horizontal axis, the cells reach a steady-state terminal velocity at which the gravitational force is mitigated by equal and opposite hydrodynamic forces, which include shear, centrifugal, and Coriolis forces. This generates an overall time-averaged gravity of 10−2 × g on the cells in culture and is referred to as SMG (7, 9, 29, 34). A HARV vessel rotated about a vertical axis provides a normal gravity (NG) control. Aeration is achieved through a semipermeable membrane at the back of the vessel.

FIG. 1.

(A)HARV system used to generate an SMG environment in ground-based investigations (reproduced with permission from Synthecon, Inc., Houston, Tex.). (B) Components of the HARV vessel. (C) Differential rotation of HARV vessels perpendicular to or parallel with the gravitational vector generates a 1-g (control) or SMG environment, respectively.

While diminished gravity compromises the human immune system, studies conducted using HARV bioreactors show that it bolsters bacterial virulence. Studies of mice orally infected with SMG-cultured Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium show that the organism colonizes liver and spleen more effectively and kills mice more rapidly; such cells also exhibit increased resistance to thermal, osmotic, and acid stresses (23, 35). This comprehensive increase of cellular robustness and virulence resembles the general stress response under NG conditions, whereby exposure to one stress, such as starvation, heat shock, or osmotic or oxidative stress, confers resistance against stresses in general (11, 16). This suggests that SMG may activate the general stress response.

The central regulating element of general stress response under NG in proteobacteria is the alternate sigma factor, σs (product of the rpoS gene). Bacterial cells exposed to individual stresses show increased levels of this sigma factor; the consequent increase in Eσs (RNA polymerase holoenzyme combined to σs) results in transcription of genes involved in increased cellular resistance (16).

This investigation was undertaken to determine if SMG confers a generalized stress resistance on Escherichia coli as well and the role of σs in this phenomenon. We included an examination of stationary growth phase in these studies, as this state is generally more representative of bacterial existence in nature (15, 16, 17); this phase was not examined in previous studies. The results show that SMG does indeed increase E. coli resistance in both exponential and stationary phases, making the latter superresistant. Further, while this increase parallels elevated σs levels in stationary phase, the opposite is true for exponential phase. We report, moreover, that SMG affects σs synthesis at all levels of control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and β-galactosidase measurement.

The bacterial strains used were as follows: E. coli AMS6 (K-12 λ− F− Δlac; 28) and isogenic mutant strains AMS150 (like AMS6 but rpoS::Tn10; 19) and AMS171 (λOLS2 Kanr). The last-mentioned strain contains a lacZ transcriptional fusion to the +82 nucleotide of the pexB coding region (14).

Bacteria were cultured in pairs of HARV reactors rotated about either a horizontal (SMG conditions) or vertical (NG conditions) axis to determine the effect of SMG. Fifty milliliters of 0.3% glucose-M9 minimal medium was used, which was supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) when required. Overnight conventional flask cultures grown in glucose-M9 medium served as inocula. The starting A660 in the HARV vessels was 0.1, and the incubation was at 37°C and 25 rpm. Under these conditions, as confirmed by counts of viable cells, the HARV cultures reached mid-exponential (A660, 0.4) and stationary (A660, 1.2) phases at 4 and 24 h of incubation, respectively.

β-Galactosidase activity was measured according to the method of Lomovskaya et al. (14) using CRPG as substrate; activity was calculated using the Miller equation (22).

Stress tests.

Ten milliliters of exponential- or stationary-phase cultures grown under SMG or NG conditions was mixed with 10 ml of either 200 mM citrate buffer (pH 3.5) or 5 M NaCl (final NaCl concentration, 2.5 M) and incubated at 37°C. Viability was determined by serial dilution on Luria-Bertani plates, as described previously (24).

σs concentration and its half-life determination.

σs was quantified by Western analysis as previously described (30, 38). Cells were mixed with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-lysis buffer (2% SDS in 0.5 M Tris-HC [pH 6.8]), and protein was quantified by the Bio-Rad Dc assay. Protein loadings were standardized at 75 μg (exponential phase) or 20 μg (stationary phase) of the total cellular protein from NG and SMG cultures, boiled for 3 min, and loaded on an SDS-12.5% polyacrylamide gel (Criterion; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). These were electroblotted onto Hybond polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, which were blocked overnight at 4°C with 5% nonfat dried milk, and washed (phosphate-buffered saline plus 1% Tween 20). A polyclonal anti-σs antibody (30) was used to probe the membranes. Blots were developed with the ECL-Plus system (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.), and σs was quantified by densitometry (Image Quant; Amersham), with a standard curve relating purified σs concentration to signal intensity.

To determine σs half-life (τ1/2σs), chloramphenicol (500 μg/ml) was added to the 50-ml HARV cultures. Samples were removed at indicated intervals, and their σs concentration was determined by Western analysis as described above. This method was used in preference to immunoprecipitation because it permitted determination of the protein half-life under HARV conditions; as it halts translation immediately, it permits an accurate half-life measurement (1).

Quantification of rpoS mRNA and its half-life determination.

Total RNA was isolated from cells grown under the specified conditions with the Masterpure kit (Epicentre, Madison, Wis.), and quantified by A260 measurements. Reverse transcription was performed on 1 μg of total RNA from each sample with the Omniscript RT kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.) and a reverse rpoS primer (5′ TTACTCGCGGAACAGCGCTT 3′). Primers for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) were designed (Beacon Designer software package; Premier Biosoft, Int.) to amplify a 131-bp internal rpoS fragment (rpoS629F, 5′ GCCGTATGCTTCGTCTTAAC 3′; rpoS759R, 5′ GTCATCTTGCGTGGTATCTTC 3′), and qPCR was performed with an iCycler iQ real-time detection system (Bio-Rad) with the QIAGEN QuantiTect Sybr Green PCR kit. Reaction mixtures (final volume for each, 20 μl) contained 1× QuantiTect MasterMix, 6 pmol of each primer, 1 μl of RT reaction mixture, and DNase-RNase-free water. Following hot start (95°C, 15 min), 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s were performed. A data acquisition step (81.5°C for 10 s) was used and set above the Tm of potential primer dimers to minimize any Sybr Green absorbance due to the dimers. Melting-curve analyses displayed a single peak at 84.5°C, indicating specific rpoS amplification. rpoS mRNA was quantified by comparing cycle thresholds to a standard curve (in the range of 103 to 108 copies), run in parallel, of the PCR-generated full-length rpoS gene; regression coefficients for the standard curves were consistently >0.99.

To determine rpoS mRNA half-life, 500 μl of rifampin (50 mg/ml dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide) was added to the 50-ml HARV cultures, and 0.5 ml of samples was removed at the indicated intervals. Samples were processed, and rpoS mRNA was quantified by qPCR, following reverse transcription as described above. The copy number was determined and plotted against time on a semilogarithmic plot, and half-life (τ1/2rpoS) was determined from the slope of a least-squares linear fit to the plot.

Calculation of σs and rpoS mRNA synthesis rates and mRNA translational efficiency.

These were calculated as described previously (38), using the following equations. To calculate the rpoS messenger synthesis rate, where τ1/2rpoS is the rpoS mRNA half-life, the following equation was used.

|

(1) |

To calculate the σs synthesis rate, where τ1/2σs is the σs protein half-life, the following equation was used.

|

(2) |

To calculate rpoS translational efficiency, where KEσs is the number of molecules of σs synthesized per copy of rpoS mRNA, the following equation was used.

|

(3) |

RESULTS

There was no significant difference in the growth rate of E. coli under NG and SMG conditions in the HARVs with the generation time of ca. 3 h. In both cases, cessation of growth was due to the exhaustion of glucose from the medium. In contrast, the generation time in conventional flask cultures in this medium was 1 h (38), indicating that HARV conditions differed from those in the flask. Nevertheless, between the two differently rotated HARVs, SMG was the primary variable.

The effect of SMG on E. coli resistance to two individual stresses—hyperosmosis or low pH—was examined in exponential- and stationary-growth phases, using the wild-type strain AMS6 and the isogenic σs-deficient strain AMS150 (19). In exponential phase, while NG-grown cells of both strains showed an almost complete loss of viability upon exposure to 2.5 M NaCl, ca. 50% of the SMG-grown cells survived (Fig. 2A). Upon transition to stationary phase, NG wild-type cells exhibited markedly greater increase in resistance than AMS150 (Fig. 2B). However, while the wild type in this phase showed a further increase in resistance upon cultivation under SMG, AMS150 did not (Fig. 2B). Note that the small difference exhibited by AMS150 grown under the two gravity conditions is not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Exposure to pH 3.5 gave similar results: exponential-phase SMG-grown cells of both strains were ca. twofold more resistant than their NG-grown counterparts (Fig. 2A); but in stationary phase, SMG conferred further resistance only on the wild type, with nearly 100% survival (Fig. 2B). Consequently, the further reinforcement of robustness made SMG-grown stationary-phase wild-type cells almost completely resistant to the two stresses.

FIG. 2.

Percent survival following exposure for 1 h to hyperosmotic (2.5 M NaCl) or acid (pH 3.5) stress in the exponential (A) or stationary (B) phase of growth. WT, wild type (AMS6); Mut, rpoS mutant (AMS150). Results represent an average of two independent measurements, each analyzed in triplicate; error bars represent standard errors of the mean. A viability of 100% corresponds to ca. 5 × 107 cells/ml.

Thus, while SMG confers resistance to the two stresses in both growth phases, this resistance is independent of σs in exponential phase but dependent on it in the stationary phase. The former situation is the first instance of general stress resistance development in E. coli without σs involvement.

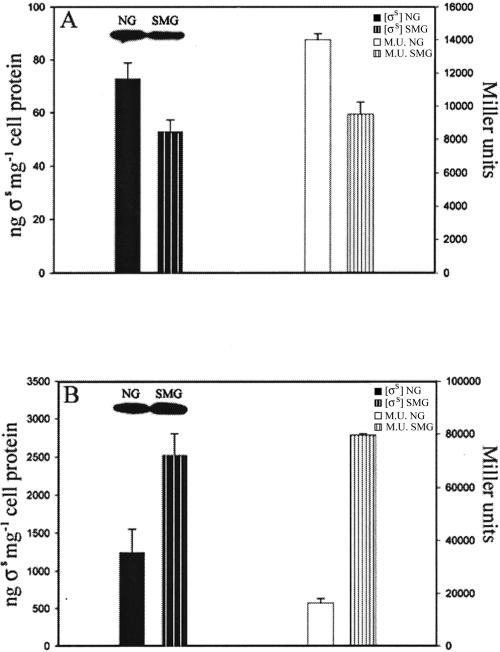

The changing roles of σs in the two growth phases under SMG raised the possibility that, in the wild type, SMG might affect σs levels differently in exponential and stationary phases. We therefore quantified the sigma levels in the two phases by Western analysis. In exponential-phase SMG cells, σs levels were consistently 30% lower than NG cells (Fig. 3A), but were 100% higher than in NG cells in stationary phase (Fig. 3B). The expression level of a σs-dependent gene (pexB) served as a further test of σs concentration: in both growth phases, the pattern of β-galactosidase synthesis of a pexB-lacZ transcriptional fusion strain (AMS171; isogenic with AMS6) (14) paralleled the measured σs levels (Fig. 3). Thus, under SMG, the paradigm that increased cellular general resistance parallels increased σs levels applied only to the stationary phase and was reversed in exponential phase, since in the latter phase increased cellular resistance coincided with lowered σs levels.

FIG. 3.

σs concentrations determined by quantitative Western analysis or inferred from the levels of β-galactosidase synthesized by a pexB-lacZ transcriptional fusion strain (E. coli AMS171) in NG or SMG cultures during exponential (A) and stationary (B) phases of growth. M. U., Miller units. Data represent an average of three independent measurements; error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

The regulation of σs under NG conditions is complex and can occur at transcriptional, posttranscriptional, translational, or posttranslational levels, depending on the stress involved (11, 16). To determine what level of control caused SMG to decrease σs concentration in one phase of growth while increasing it in the other, we conducted a detailed analysis of the effect of SMG on molecular regulation of σs synthesis. The steady-state rpoS mRNA copy number was quantified by qPCR. In NG- and SMG-grown cells, this number was nearly identical regardless of the growth phase. Under both gravity conditions, the copy number showed a 10-fold decrease upon transition from exponential to stationary phase (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Transcriptional parameters of rpoS synthesis of exponential- and stationary-phase NG and SMG cultures.a

| Growth phase |

rpoS mRNAb [rpoS]

|

mRNA half-lifec (τ1/2rpoS)

|

Transcriptional rated (KsRNA)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NG | SMG | NG | SMG | NG | SMG | |

| Exponential | 1.3 × 108 | 1.3 × 108 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 1.6 × 107 | 1.6 × 107 |

| Stationary | 1.4 × 107 | 1.3 × 107 | 34.5 | 72.1 | 2.8 × 105 | 1.2 × 105 |

Each value is an average of at least two independent determinations with analytical triplicates; standard error of the mean was <8%.

Copies of rpoS mRNA per microgram of total RNA.

Message half-life (minutes).

Copies of rpoS synthesized per microgram of total RNA per minute.

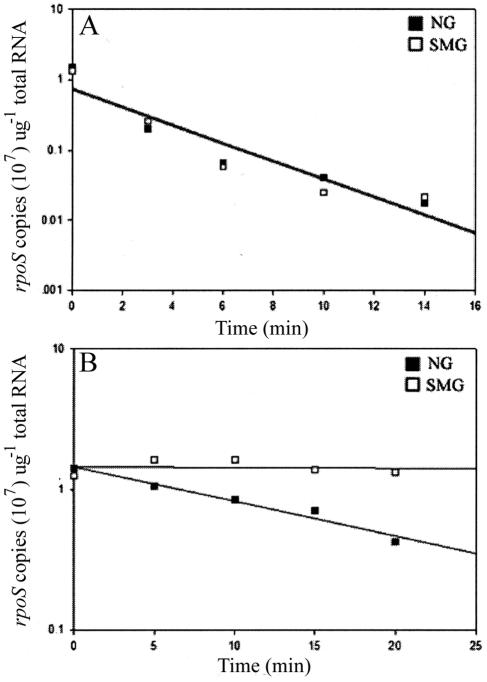

Since steady-state levels of an mRNA could reflect its synthesis rate, stability, or both, the rpoS messenger half-life (τ1/2rpoS) was measured (Materials and Methods). As the half-life of the message was the same in exponential phase under the two gravity conditions (Fig. 4A), it follows that the transcriptional rate (equation 1) of the rpoS gene (KsrpoS) in this phase was not affected by SMG (Table 1). This is consistent with the microarray analysis of Wilson et al. (36), who found that SMG growth does not affect rpoS transcription in exponential phase. The messenger stability increased in stationary phase under both gravity conditions, but was twofold higher in SMG- than in NG-grown cells (Fig. 4B), indicating that the rate of rpoS transcription decreased by twofold in stationary-phase SMG compared to NG cells (Table 1).

FIG. 4.

rpoS message half-life of NG and SMG cells in exponential (A) and stationary (B) growth phases. Data represent an average of at least two independent qPCR measurements, with each time point analyzed in triplicate.

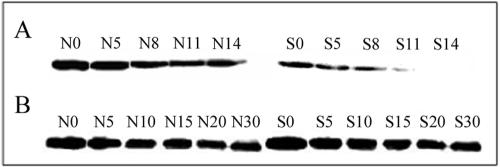

Regulation at the transcriptional level can therefore not account for the differential effect of SMG on σs levels in the two growth phases. We thus determined SMG effect on other levels of control of σs synthesis. σs stability was determined by measuring its half-life, as described in Materials and Methods. SMG markedly shortened the half-life of the sigma protein in exponential-phase cells (Fig. 5A and Table 2). In stationary phase, the sigma protein became more stable under both conditions; however, σs remained less stable in SMG than in NG by a small, but reproducible, value (Fig. 5B and Table 2).

FIG. 5.

σs protein half-life determined by quantitative Western analysis during the exponential (A) or stationary (B) phase of growth; representative Western blots are shown. N values (N0, N5, etc.) and S values (S0, S5, etc.) represent sampling time points in minutes under NG and SMG conditions, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Translational parameters of σs synthesis of exponential- and stationary-phase NG and SMG culturesa

| Growth phase | σs proteinb [σs]

|

σs half-lifec (τ1/2σs)

|

Translational rated (Ksσs)

|

Translational efficiencye (KEσs)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NG | SMG | NG | SMG | NG | SMG | NG | SMG | |

| Exponential | 73 | 53 | 16.4 | 5.2 | 3.1 | 7.0 | 3.6 × 1011 | 8.4 × 1011 |

| Stationary | 1,263 | 2,530 | 28.8 | 24.6 | 30.4 | 71.2 | 3.3 × 1013 | 8.5 × 1013 |

Each value is an average of at least two independent determinations with analytical triplicates; standard error of the mean was <8%.

Nanograms σs per milligram of protein.

Protein half-life (minutes).

Nanograms of σs synthesized per milligram of cell protein per minute.

Molecules of σs synthesized per copy of rpoS mRNA per minute.

From the steady state σs concentrations, its half-life, and the rpoS mRNA copy number, the rpoS mRNA translational rate (equation 2) and efficiency (equation 3) were calculated. Both the translational rate and efficiency increased markedly in stationary phase compared to exponential phase; in both phases, these parameters were higher in SMG than in NG-grown cells (Table 2). Thus, the main reasons for the differential effect of SMG on σs levels in the two phases are that it renders the sigma protein much more labile in the exponential than in the stationary phase and increases rpoS mRNA translational efficiency.

DISCUSSION

The HARV-grown NG cells of E. coli showed σs-dependent increased resistance in stationary phase to the stresses tested and elevated σs concentration in this phase, due largely to the stabilization of this protein. In both respect, the HARV cultures resembled conventional flask cultures in responding to stress (11, 24, 30), indicating that the use of the HARV reactors per se did not influence the stress response and that therefore these reactors are suitable for investigating SMG effects.

SMG enhanced E. coli resistance to both osmotic and acid stresses. That resistance developed simultaneously to two very different stresses strongly suggests that SMG conferred comprehensive cellular resistance. This conclusion is bolstered by the fact that Gao et al. (6) have shown that SMG also makes E. coli more resistant to ethanol stress.

The SMG effect in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium has been previously examined, but only in the exponential phase. The bacterium developed general resistance under this gravity condition in this phase independently of σs, since an rpoS mutant behaved like the wild type (35). Further, resistance developed without the induction of σs-regulated genes, such as dnaK, groEL, and pexB (dps) (36) that, by preventing cell macromolecular damage and promoting repair, mechanistically contribute to comprehensive cellular resistance in conventional flask cultures (10, 16). The findings with E. coli reported here not only reinforce the conclusion of Wilson et al. (36) that exponential-phase SMG-conferred general resistance is independent of σs, but they show further that in the wild-type E. coli, it is accompanied by diminished levels of this sigma factor. Thus, there appears to be an as-yet-undiscovered mechanism of comprehensive cellular resistance, which is not accompanied by increased σs levels and may not involve increased expression of known stress resistance genes.

SMG-grown E. coli cells were also more resistant than their NG-grown counterparts in stationary phase; since the latter are already quite robust, this results in superresistant cells. In contrast to exponential phase, the more normal situation of a direct relationship between σs levels and increased resistance prevails in the stationary phase (10, 16), as the highly resistant SMG stationary-phase cells possess higher σs concentrations than NG cells.

Conditions resembling the stationary phase are the norm in nature (15, 16, 17), and since SMG renders such cells superresistant, it follows that the SMG effect on bacterial resistance is even a greater cause for concern for space exploration than previously indicated by studies with exponential-phase cells (23, 35, 36). SMG conditions resemble low-shear environments on Earth, such as the brush border microvilli of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and urogenital tracts (4, 8, 31). These are common routes of microbial infection, and therefore an understanding of the mechanism of SMG-conferred resistance will also contribute to a better control of infectious disease on this planet.

Apart from altering the dependence of stress resistance on σs in the two growth phases, SMG also profoundly affects σs regulation with respect to its stability and the translational efficiency of its mRNA. Studies conducted with conventional flask cultures have shown that σs stability is governed by its cleavage by ClpXP protease in which the phosphorylated form of a “tethering” response regulator protein is believed to play a role (12, 25, 30). As the extent of RssB phosphorylation may be a factor in determining σs stability (10), it is conceivable that SMG promotes RssB phosphorylation, thereby increasing σs instability. An additional possibility regarding the effect of SMG on the stability of this sigma factor relates to the fact that ClpXP protease activity is greatly affected by the folding pattern of its substrate (12). Previous studies show that space microgravity influences protein crystal formation (21), which suggests that diminished gravity and shear may influence protein-folding patterns. If so, σs folding under SMG might be altered, making it a more suitable target for ClpXP cleavage.

What might underlie the increased translational efficiency of the rpoS mRNA under SMG conditions in the two growth phases? rpoS translational efficiency under NG conditions, as obtained with conventional flask cultures, is thought to be regulated by two types of secondary structures, one formed within the untranslated region of the messenger (26) and the other between the anti-sense element in the coding region and the translational apparatus (18). Proteins such as Hfq and several small RNAs play a role in promoting secondary structures of the rpoS mRNA which possess different translational competence. SMG can conceivably affect this phenomenon. The lack of gravity may minimize tendency of the mRNA towards secondary structure formation and/or promote interaction between Hfq, rpoS mRNA, and the small RNA, such as DsrA, which acts as a positive regulator of translation of this messenger (32). These hypotheses are under investigation.

While the mechanistic basis of SMG effect on cell resistance at this stage must remain speculative, it is clear that this gravity condition introduces a new comprehensive cellular resistance paradigm and promises to shed light on basic mechanisms that regulate translational control and proteolysis. Insights into these phenomena are important not only for the safety of space travel, but also in enhancing our understanding of fundamental biological processes on Earth.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NASA Grant NNA04CC51G. S.V.L. was supported, in part, by a Deans Fellowship from Stanford University, School of Medicine.

We thank Arnold Demain for introducing us to the field of microgravity and David Ackerley, Ralph Selke, and Mimi Keyhan for helpful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Audia, J. P., and J. W. Foster. 2003. Acid shock accumulation of σs in Salmonella enteritica involves increased translation, not regulated degradation. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 5:17-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakos, A., A. Varkonyi, J. Minarovits, and L. Batkai. 2001. Effect of simulated microgravity on human lymphocytes. J. Gravit. Physiol. 8:69-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakos, A., A. Varkonyi, J. Minarovits, and L. Batkai. 2002. Effect of simulated microgravity on the production of IL-12 by PBMCs. J. Gravit. Physiol. 9:293-294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai, Z., J. Xin, D. M. Pollock, and J. S. Pollock. 2000. Shear stress-mediated NO production in inner medullary collecting duct cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 279:F270-F274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Criswell-Hudak, B. S. 1991. Immune response during space flight. Exp. Gerontol. 26:289-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao, Q., A. Fang, D. L. Pierson, S. K. Mishra, and A. L. Demain. 2001. Shear stress enhances microcin B17 production in a rotating wall bioreactor, but ethanol stress does not. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 56:384-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodwin, T. J., T. L. Prewett, D. A. Wolf, and G. F. Spaulding. 1993. Reduced shear stress: a major component in the ability of mammalian tissues to form three-dimensional assemblies in simulated microgravity. J. Cell. Biochem. 51:301-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo, P., A. M. Weinstein, and S. Weinbaum. 2000. A hydrodynamic mechanosensory hypothesis for brush border microvilli. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 279:F698-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond, T. G., and J. M. Hammond. 2001. Optimised suspension culture: the rotating-wall vessel. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 281:F12-F25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2002. Recent insights into the general stress response regulatory network in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:341-346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2002. Signal transduction and regulatory mechanisms involved in control of the σs (RpoS) subunit of RNA polymerase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:373-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenniston, J. A., R. E. Burton, S. M. Siddiqui, T. A. Baker, and R. T. Sauer. 2004. Effects of local protein stability and the geometric position of the substrate degradation tag on the efficiency of ClpXP denaturation and degradation. J. Struct. Biol. 146:130-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leach, C. S. 1992. Biochemical and hematologic changes after short-term space flight. Microgravity Q. 2:69-75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lomovskaya, O. L., J. P. Kidwell, and A. Matin. 1994. Characterization of the sigma 38-dependent expression of a core Escherichia coli starvation gene, pexB. J. Bacteriol. 176:3928-3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matin, A. 1981. Regulation of enzyme synthesis as studied in continuous culture, vol. II. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.

- 16.Matin, A. 2000. Stress response in bacteria. Encyclopedia of environmental microbiology, 6:. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 17.Matin, A., and H. Veldkamp. 1978. Physiological basis of the selective advantage of a Spirillum sp. in a carbon-limited environment. J. Gen. Microbiol. 105:187-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCann, M. P., C. D. Fraley, and A. Matin. 1993. The putative sigma factor KatF is regulated posttranscriptionally during carbon starvation. J. Bacteriol. 175:2143-2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCann, M. P., J. P. Kidwell, and A. Matin. 1991. The putative sigma factor KatF has a central role in development of starvation-mediated general resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173:4188-4194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McPhee, J. C., and R. J. White. 2003. Physiology, medicine, long-duration space flight and the NSBRI. Acta Astronaut. 53:239-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miele, A. E., L. Federici, G. Sciara, F. Draghi, M. Brunori, and B. Vallone. 2003. Analysis of the effect of microgravity on protein crystal quality: the case of a myoglobin triple mutant. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 59:982-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 23.Nickerson, C. A., C. M. Ott, S. J. Mister, B. J. Morrow, L. Burns-Keliher, and D. L. Pierson. 2000. Microgravity as a novel environmental signal affecting Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium virulence. Infect. Immun. 68:3147-3152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandza, S., M. Baetens, C. H. Park, T. Au, M. Keyhan, and A. Matin. 2000. The G-protein FlhF has a role in polar flagellar placement and general stress response induction in Pseudomonas putida. Mol. Microbiol. 36:414-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pruteanu, M., and R. Hengge-Aronis. 2002. The cellular level of the recognition factor RssB is rate-limiting for σs proteolysis: implications for RssB regulation and signal transduction in σs turnover in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1701-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Repoila, F., N. Majdalani, and S. Gottesman. 2003. Small non-coding RNAs, co-ordinators of adaptation processes in Escherichia coli: the RpoS paradigm. Mol. Microbiol. 48:855-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savary, C. A., M. L. Grazziuti, D. Przepiorka, S. P. Tomasovic, B. W. McIntyre, D. G. Woodside, N. R. Pellis, D. L. Pierson, and J. H. Rex. 2001. Characteristics of human dendritic cells generated in a microgravity analog culture system. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 37:216-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.J. E., Schultz, G. I. Latter, and A. Matin. 1988. Differential regulation by cyclic AMP of starvation protein synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 170:3903-3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwarz, R. P., T. J. Goodwin, and D. A. Wolf. 1992. Cell culture for three-dimensional modeling in rotating-wall vessels: an application of simulated microgravity. J. Tissue Cult. Methods 14:51-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schweder, T., K. H. Lee, O. Lomovskaya, and A. Matin. 1996. Regulation of Escherichia coli starvation sigma factor (σs) by ClpXP protease. J. Bacteriol. 178:470-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stock, U. A., and J. P. Vacanti. 2001. Cardiovascular physiology during fetal development and implications for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 7:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Storz, G., J. A. Opdyke, and A. Zhang. 2004. Controlling mRNA stability and translation with small, noncoding RNAs. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:140-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor, G. R., and J. R. Dardano. 1984. Human cellular immune responsiveness following space flight. Kosm. Biol. Aviakosm. Med. 18:74-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Unsworth, B. R., and P. I. Lelkes. 1998. Growing tissues in microgravity. Nat. Med. 4:901-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson, J. W., C. M. Ott, R. Ramamurthy, S. Porwollik, M. McClelland, D. L. Pierson, and C. A. Nickerson. 2002. Low-shear modeled microgravity alters the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium stress response in an RpoS-independent manner. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5408-5416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson, J. W., R. Ramamurthy, S. Porwollik, M. McClelland, T. Hammond, P. Allen, C. M. Ott, D. L. Pierson, and C. A. Nickerson. 2002. Microarray analysis identifies Salmonella genes belonging to the low-shear modeled microgravity regulon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13807-13812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woods, C. C., K. E. Banks, R. Gruener, and D. DeLuca. 2003. Loss of T cell precursors after spaceflight and exposure to vector-averaged gravity. FASEB J. 17:1526-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zgurskaya, H. I., M. Keyhan, and A. Matin. 1997. The sigma S level in starving Escherichia coli cells increases solely as a result of its increased stability, despite decreased synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 24:643-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]