Abstract

The distal-half tail fiber of bacteriophage T4 is made of three gene products: trimeric gp36 and gp37 and monomeric gp35. Chaperone P38 is normally required for folding gp37 peptides into a P37 trimer; however, a temperature-sensitive mutation in T4 (ts3813) that suppresses this requirement at 30°C but not at 42°C was found in gene 37 (R. J. Bishop and W. B. Wood, Virology 72:244-254, 1976). Sequencing of the temperature-sensitive mutant revealed a 21-bp duplication of wild-type gene 37 inserted into its C-terminal portion (S. Hashemolhosseini et al., J. Mol. Biol. 241:524-533, 1994). We noticed that the 21-amino-acid segment encompassing this duplication in the ts3813 mutant has a sequence typical of a coiled coil and hypothesized that its extension would relieve the temperature sensitivity of the ts3813 mutation. To test our hypothesis, we crossed the T4 ts3813 mutant with a plasmid encoding an engineered pentaheptad coiled coil. Each of the six mutants that we examined retained two amber mutations in gene 38 and had a different coiled-coil sequence varying from three to five heptads. While the sequences varied, all maintained the heptad-repeating coiled-coil motif and produced plaques at up to 50°C. This finding strongly suggests that the coiled-coil motif is a critical factor in the folding of gp37. The presence of a terminal coiled-coil-like sequence in the tail fiber genes of 17 additional T-even phages implies the conservation of this mechanism. The increased melting temperature should be useful for “clamps” to initiate the folding of trimeric β-helices in vitro and as an in vivo screen to identify, sequence, and characterize trimeric coiled coils.

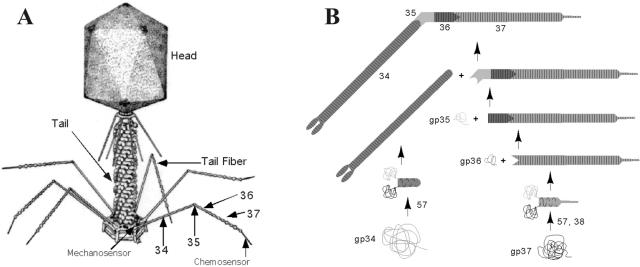

Escherichia coli bacteriophage T4 is a complex nanomachine assembled from DNA and protein. It is composed of four major structural components: a genome of DNA, a head, a tail, and tail fibers (TFs) (Fig. 1). Most, or all, T4 virion structural proteins are transcribed and translated during the late period of infection. The assembly processes of the three protein structural components (head, tail, and TFs) occur in parallel with the aid of a group of chaperones (39, 40). Nearly all of these chaperones are proteins encoded by genes in the T4 genome (10). They help to regulate the folding and assembly of T4 proteins and are not included in the final functional structure of the virion.

FIG. 1.

Bacteriophage T4 structures. (A) Virion; (B) TF self-assembly.

The T4 long TFs (LTFs) are critical for the first steps of viral infection (11, 12). The chemosensors in the carboxy-terminal region of the LTFs recognize the host cell by binding (reversibly) to receptors displayed on the cell surface (14). The phage then attaches to the cell irreversibly via P12 (short TFs) (31). Each LTF on the phage has a rod-like structure that consists of proximal- and distal-half TFs of approximately equal lengths, joined at their ends in an angle (39). Proximal-half LTFs are parallel homotrimers of matured gp34 (called P34, where P denotes the homooligomeric assembly of the monomeric gene product, gp34). Distal-half fibers contain a monomer of gp35, a homotrimer of gp36 (P36), and a homotrimer of gp37 (P37). Though it had long been suspected that P34, P36, and P37 were dimeric in mature LTFs with only a single copy of gp35 (5, 7), the Steven lab (4) demonstrated by scanning transmission electron microscopy that P34, P36, and P37 were trimeric homooligomers. We have confirmed this finding by analytical ultracentrifugation and comparison of the molecular weights of whole LTFs to LTFs with 346 (out of 1,026) residues deleted from gp37 (Y. Sheik, W. Stafford, P. Hyman, and E. B. Goldberg, unpublished data).

The folding and oligomerization of the TFs is regulated by chaperones encoded by genes 57A (23) and 38 (9). Chaperone P57A participates in the assembly of P34 and P37 and also in the assembly of the short TF, P12 (15, 19). P38 is necessary (in addition to P57A) for the trimerization of gp37 to form the mature P37 rod, which initiates the extension of LTF assembly (9, 13). The order of assembly of the distal-half fiber starts with the maturation of three gp37 monomers into the P37 trimer. Then, three gp36 monomers bind to the N terminus of the P37 trimer and mature into the P36-P37 rod. This event is followed by the addition of one gp35 molecule to the N terminus of the mature trimeric P36 LTF segment to complete the distal-half fiber. The P34 trimer can then join to the gp35 end of the distal-half fiber at an angle to form a complete LTF (20). Although it is certain that chaperones P57A and P38 are involved in distal-half fiber assembly, the binding sites, order of interactions, and mechanisms of their functions are still not clear.

A temperature-sensitive mutation (ts3813) that suppresses the requirement for P38 function at 30°C but not at 42°C was found in gene 37 (which codes for gp37) (2). The authors initially speculated that P38 may catalyze the noncovalent association of two gp37 molecules. A comparison of the wild-type T4 sequence of gene 37 to the mutant sequence (12) showed a 21-bp duplication of gene 37 inserted between nucleotides 3328 and 3329, near its C terminus (Table 1, first and second rows). They speculated that the extended sequence is responsible for the maturation of gp37 to P37 in the absence of P38. We recognized that the extended 21-nucleotide sequence in the ts3813 mutant had a coiled-coil (CC) motif within a CC diheptad present in wild-type T4. When we tested the peptide sequence by using COILS (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/COILS_form.html), the extended 21-nucleotide sequence in the ts3813 mutant was predicted to have a 98.4% CC-forming probability (when the window size was 21 residues), while in wild-type gene 37 protein, the same region of a 15-amino-acid (aa) sequence exhibited much lower CC formation probabilities (0.714 with a window size of 14 residues and 0.020 with a window size of 21 residues). Cerritelli et al. also examined the protein sequence of all of the segments of wild-type T4 TF (4) and, although 2.5 “possible” heptads were identified in this region, concluded that α-helical coiled coils were “at most a minimal element in the LTF.”

TABLE 1.

DNA and amino acid sequences of recombinant T4 phages

| Heptad name | Growth at nonpermissive tempa:

|

Amino acid at indicated position in heptad:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30°C | 37°C | 50°C | 1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | a | ||||

| WT | + | + | + | F | A | N | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | K | T | D | I | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ts3813 | + | − | − | F | A | N | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | K | T | D | I | ||||||||||||||

| SQ3A | + | + | + | F | A | N | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | K | T | E | I | E | S | L | K | T | E | I | ||||||||||||||

| SQ4A | + | + | + | F | A | N | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | K | T | D | I | E | S | L | K | T | E | I | E | S | L | K | T | E | I | |||||||

| SQ4B | + | + | + | F | A | N | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | K | T | E | I | E | S | L | K | T | E | I | |||||||

| SQ4C | + | + | + | F | A | N | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | K | T | E | I | E | S | L | K | T | D | I | |||||||

| SQ4D | + | + | + | F | A | N | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | K | T | D | I | E | S | L | K | T | E | I | E | S | L | K | T | D | I | |||||||

| SQ5A | + | + | + | F | A | N | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | K | T | D | I | E | S | L | K | T | E | I | E | S | L | K | T | D | I |

| pT7-5/37hep5 (plasmid) | F | A | N | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | N | S | T | I | E | S | L | K | T | D | I | E | S | L | K | T | E | I | E | S | L | K | T | E | I | |||

Growth at nonpermissive temperatures was on the host strain BB. All strains formed plaques on B40su+ at the permissive temperatures shown.

We hypothesized that a short trimeric CC that was brought into alignment and stabilized by the P38 chaperone protein could efficiently initiate the upstream folding of the thick β-structural rod (1, 4, 17). The corollary was that by adding the third heptad, the enhanced stability of the ts3813 bypass mutation would make an intrinsically more stable CC (a clamp) and thereby relieve the requirement for P38 at 30°C but not at 42°C (2). (We found that the ts3813 mutation fails to suppress P38 mutations even at 37°C.)

In this paper, we report the design and construction of a series of T4 phages with longer or putatively more stable CC-like heptads in gp37 that enable P38 chaperone bypass at temperatures ranging from 30 to 50°C in vivo. From the phenotypic differences of the T4 series and the fact that all of the bypass mutants that we found had 7-, 14-, or 21-residue inserts, we conclude that the extended CC region is responsible for the initiation of P37 trimeric assembly and acts as an artificial cis chaperone to bypass the need for P38.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and bacteriophages.

Wild-type and pseudorevertant T4 phage stocks were grown in E. coli BBsu0 by using our standard protocols (16). P38 amber mutant T4 phage stocks were grown in E. coli B40suI (a supD strain). Phage T4 37ts3813 38amB262amC290 was the kind gift of William Wood. E. coli MC1061 rk− mk+ was the kind gift of Hongshan Li.

Construction of a plasmid encoding an extended CC.

In order to add an extended CC to T4 phage P37, we began with the plasmid pT7-5/37ts3813 (P. Durham and E. B. Goldberg, unpublished data), a clone of the T4 gene 37ts3813 mutant placed in the T7 expression construct pT7-5 (34). Additional heptad-encoding DNA segments were designed with the MultiCoil and COILS programs (see below), and oligonucleotides were synthesized at the Tufts University Core Facility. Equimolar amounts of the 5′-phosphorylated oligonucleotides BlBDZ-F (5′-ATTGAATCACTTAAGACAGAA-3′) and BlBDZ-R (5′-TTCTGTCTTAAGTGATTCAAT-3′) were mixed, boiled, and slow-cooled to anneal the two oligonucleotides. The double-stranded oligonucleotide was then ligated to the EcoRV-digested pT7-5/37 ts3813 mutant (EcoRV fortuitously cuts uniquely at the 3′ end of the CC-encoding segment between the final heptad g and a positions, encoding residues D and I). Following ligation, the new construct was introduced into E. coli MC1061 by using heat shock according to standard methods (28). The resulting plasmids were screened for multiple inserts in the correct orientation by sequencing (Tufts University Core Facility). The final construct encodes gene 37 with a pentaheptad CC (35 aa) and is designated pT7-5/37hep5 (whose protein sequence is shown in the last row of Table 1).

Recombination of plasmid DNA and T4 phage genome.

We transformed E. coli B40suI cells with pT7-5/37hep5 by using routine protocols and antibiotic screening. From an overnight culture, we made a fresh log-phase culture in the same medium (L broth with 100 μg of ampicillin per ml) supplemented with 0.2% glucose at 30°C, and cells were grown to a density of 2 × 108 cells per ml. We infected the plasmid-carrying cells with T4 37ts3813 38amB262amC290 phage at a multiplicity of infection of 5. After incubation for 1 h, 50 μl of chloroform was added to lyse the cells, and the culture was incubated for an additional 5 min. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and stored at 4°C.

Selection and screening of phages.

We determined the titers of phage from the lysates of the recombination on a lawn of E. coli B40suI grown at 37°C overnight. From these plates, we chose individual plaques at random and spotted them in duplicate on lawns of E. coli BB and B40. One plate of each host bacterial strain was incubated at 30°C, and the other was incubated at 37°C overnight. In this way, we identified phage that formed plaques at both temperatures on both hosts. These plaques were resuspended and used as templates from which to amplify the CC region of gene 37 by PCR according to the protocol of Jozwik and Miller (18). The primers 37RV-1F (5′-GTTCTGGTAATTTTGCTAAC-3′) and 37RV-1R (5′-AACAGCTAACTTTGGATATG-3′) were used to amplify short segments that included all of the CC. In order to identify the heptad number in each mutant phage amplicon, we ran 2.2% agarose gels in Tris-borate-EDTA running buffer. These gels were used to screen for different CC lengths. To determine the precise CC nucleotide composition, we selected amplified fragments for DNA sequencing. To confirm the retention of the two amber mutations within gene 38, we also amplified gene 38 with primers gp38F (5′-AGCATAAGGAGAGGGGCTTC-3′) and gp38R (5′-CTAGGTGCTGCCATAGACCC-3′) and sequenced the product.

Temperature testing of phage mutants.

To determine the range of in vivo temperature stability of multiheptad mutants, resuspended plaques were plated on E. coli BB and B40 at 30, 37, 42, 45, and 50°C overnight and counted. Serial plating at various temperatures with identical methods was used to investigate heptad stability.

Secondary-structure prediction and sequence alignments.

COILS version 2.2 (22) was employed to predict the probability of CC structures in protein sequences. This program uses a single sequence-based prediction algorithm for CC regions by using statistical patterns of CC proteins within a database of known CC sequences. For all COILS analyses reported here, the MTIDK matrix was used for scoring. No weighting of positions was applied, and window sizes of 14 and 21 residues were used. Related analysis was also performed using a 28-residue window on MultiCoil (38; http://multicoil.lcs.mit.edu/cgi-bin/multicoil), which models probabilities of both dimeric and trimeric CC structures. Here, the CC probability cutoff was set at 0.5. TF sequences were analyzed as described above. Predicted CC sequences were aligned and phylogenetic trees were generated by using the CLUSTAL W version 1.75 (37) and the GeneBee multiple alignment program (25; www.genebee.msu.su).

RESULTS

Selection and screening of phenotypes of T4 with a recombinant genome.

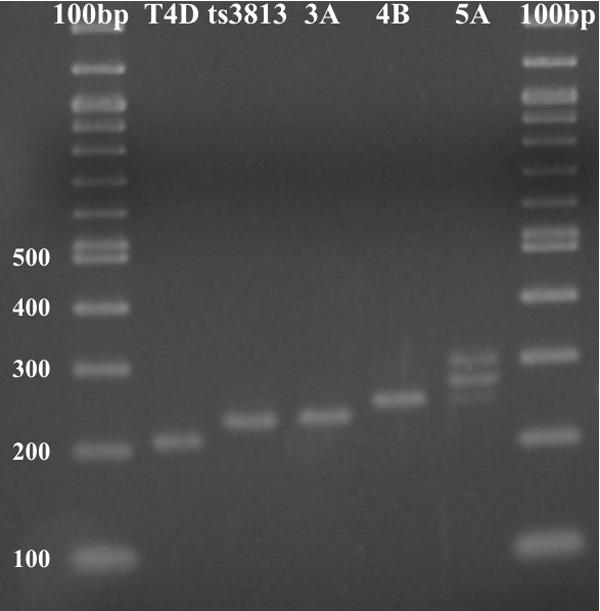

Plaques from the recombination between the phage T4 37ts3813 38amB262amC290 and the plasmid pT7-5/37Hep5 that grew on E. coli BB at 37°C or higher were selected for subsequent screening. Initially, we used PCR to amplify the CC-encoding segment of gene 37 to screen for the length of the CC by using agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2). We observed a distribution of lengths in the CC region, which indicated the presence of three-, four-, and five-heptad variants. A minimum of five of these phages for each heptad length were then sequenced. Sequencing of gene 38 was used to confirm that each of the phages retained the upstream amC290 and amB262 mutations in gene 38 (to prevent production of the chaperone P38).

FIG. 2.

PCR of the coiled-coil segments of genes 37 of various phage strains.

Genetic recombination between the CC sequences of the pentaheptad DNA construct in the plasmid and the triheptad CC in phage T4/ts3813 38am produced one new triheptad phage, T4/SQ3A; four different tetraheptad phages, T4/SQ4A, T4/SQ4B, T4/SQ4C, and T4/SQ4D; and one new pentaheptad phage, T4/SQ5A (Table 1). Because the CC in pT7-5/37hep5 is derived from the CC in the T4/ts3813 parent phage, it is impossible to identify the exact recombination junctions.

We next tested the novel phages for growth at elevated temperatures. gp38 chaperone bypass was observed in cultures at nonpermissive temperatures of up to 50°C (Table 1, 2nd column) for all of the extended CC mutants, while ts3813 controls were unable to form plaques at 37°C and above. All of the phages grow at all of the temperatures in permissive cells. Sequencing of gene 38 confirmed that the two amber mutations which prevent the expression of gp38 were unchanged. It also showed that both amber mutations were G-to-A point mutations at bases 159846 and 159933 (using numbering conventions from the NCBI database, accession number NC_00086). These mutations correspond to stop codons introduced into gp38 amino acids W66am and W95am.

Although the CC was generally stable, a recombination that reduced its length continued to occur during serial plating. This continuation was primarily observed in the case of the pentaheptad mutant, SQ5A, where tetraheptad plaques were occasionally found after several rounds of serial plating. We did not conduct a systematic study of heptad reduction rates. In no case, however, did we find spontaneous reversion to the wild-type diheptad CC even after three rounds of plating. Importantly, in all plaques sequenced, the CC region contained integral multiples of heptad repeats—no partial heptads were observed. This finding supports the hypothesis that the CC motif is required.

COILS and MultiCoil predictive modeling.

COILS analysis of the entire wild-type gene 37 protein sequence suggested that the 15-aa segment FANLNSTIESLKTDI (aa 795 to 809) exhibited some CC formation probabilities (0.714 with a window size of 14 residues and 0.020 with a window size of 21 residues). No other CC regions were predicted in the remainder of gp37. The one heptad elongation of this region found in the mutant phage 37ts3813 has an even higher CC-forming probability (0.806 with a window size of 14 residues and 0.984 with a window size of 21 residues), suggesting significant homology to other known CC structures. MultiCoil analysis of the sequence yielded lower CC probabilities for the 37ts3813 mutant, with a maximum overall probability of 0.124 occurring in an 18-residue segment largely overlapping the triheptad region (residues 793 to 810). Interestingly, MultiCoil predicts very low but nearly equivalent dimer and trimer probabilities of 0.055 and 0.070, respectively.

We also analyzed the novel CC sequences found in the recombinant phages without the surrounding gp37 sequence (data not shown). All of the sequences have a high probability of forming a CC for both window sizes. Furthermore, we analyzed the longer sequences by using MultiCoil to see how they compare to other dimeric and trimeric CC proteins in its database. Surprisingly, although P37 is known to be a homotrimeric protein, all of the sequences are predicted to be homodimeric CCs.

CCs in other T-even phages.

A GenBank search identified 21 protein sequences of gp37 equivalents from bacteriophages that are morphologically similar to bacteriophage T4. These phages are classified as Myoviridae but often called T-even-like phages (36). Of the 21 sequences, 15 are complete protein sequences, while the remaining 6 sequences comprise only the C terminus of the protein. The sequences represent 19 different phages, among which two phages, Aeh1 and RB43, each have two genes encoding analogues of T-even-like gp37. In both cases, these genes appear to be fusions of gp36 and gp37. It is not known if both or only one is expressed. Each of the 21 sequences was analyzed with COILS. All but one of the sequences (phage 44RR2.8t, GenBank accession number AAQ81539) contained a sequence with homology to known CC segments. Interestingly, eight of the sequences contained more than one potential CC sequence, although in most of these sequences, one of the segments had a much higher probability of forming a CC than the others. These putative CC sequences are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Potential coiled-coil sequences from T-even-like bacteriophage

| Phage name | Protein accession no. | Total sequence length (aa) | Predicted leucine zipper position (COILS maximum probability) | Predicted coiled-coil sequence at heptad positionc: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| abcdfgabcdefgabcdefgabcdefgabcdefgabc | ||||

| AC3 | AAC62007 | 1,103 | 994-1013 (0.559) | DIRVKKNLVKFENASEKLSK |

| 1070-1103 (1.000) | IGLNTAAINEHTAEIAELKSEIEELKKLVKSLLK | |||

| Aeh1 gene 1 | AAQ17985 | 1,358a | 1333-1358 (1.000) | SGVNALLVEAIKELRAELNELKSKLN |

| Aeh1 gene 2 | AAQ17987 | 1,303a | 168-195 (0.695) | TDKLTTDLATANTKIDTLDAQNVKLTGD |

| AR1 | Q9G0B5 | 1,103 | 1070-1103 (1.000) | IGLNTAAINEHTAEIAELKSEIEELKKIVKSLLK |

| K3 | Q38394 | 1,243 | 1214-1243 (0.976) | TVSSQAQIALLVEAVKTLSARVKELESKLM |

| KVP40 | AAQ64368 | 1,094 | 1062-1094 (1.000) | GNMVGLLIEGIKEEKRKREALEERIARLEALLS |

| M1 | P08231 | 251 (C terminus) | 186-203 (0.559) | AQDLEKELPEAVSKVEVD |

| 212-236 (0.998) | NSAVNALLIKAIQEMSEEIKELKTP | |||

| Ox2 | P08232 | 251 (C terminus) | 186-203 (0.559) | AQDLEKELPEAVSKVEVD |

| 212-236 (0.998) | NSAVNALLIKAIQEMSEEIKELKTP | |||

| PP01 | AAK30164 | 1,109 | 1076-1109 (1.000) | IGLNTAAINEHTAEIAELKSEIEELKALVKSLLK |

| RB27 | AAC27317 | 305 (C terminus) | 272-305 (1.000) | IGLNTAAINEHTAEIAELKSEIEELKALVKSLLK |

| RB43 gene 1 | AAP04368 | 756a | 658-681 (0.946) | RSDEKLKSNFNKIENALDKVELLN |

| 732-756 (1.000) | TATIALLVEAIKELREEVRELKSRQ | |||

| RB43 gene 2 | AAP04369 | 812a | 717-738 (0.912) | IRLKSNLVELKDALSKVEQLKG |

| 787-812 (1.000) | SVNALLITAINELRERLEAIERKIGA | |||

| RB49 | AAQ15494 | 979 | 872-895 (0.864) | DARLKINKEEYKENATDKVNRLTV |

| 948-979 (1.000) | NSAVNALLIKAFQEMSEELKAVKAELEELKKN | |||

| RB69 | AAP76153 | 1,103 | 997-1013 (0.559) | VKKNLVKFENASEKLSK |

| 1067-1103 (1.000) | NGVIGLNTAAINEHTAEIAELKSEIEELKKLVKSLLK | |||

| SV14 | CAA91919 | 267 (C terminus) | 1-11b | NSTIESLKTDI |

| T2 | P07067 | 1,34 | 1312-1341 (0.976) | TVSSQAQIALLVEAVKTLSARVKELESKLM |

| T4 | AAD42460 | 1,026 | 795-809 (0.714) | FANLNSTIESLKTDI |

| T6 | AAC61976 | 993 | 646-661 (0.624) | DSNNARDNIIQLEDSK |

| 927-943 (0.559) | AQDLEKELPEAVSKVEV | |||

| 953-977 (0.998) | NSAVNALLIKAIQEMSEEIKELKTP | |||

| Tu1a | S13237 | 382 (C terminus) | 114-130 (0.714) | FANLNSTIESLKTDIVS |

| Tu1b | S13239 | 267 (C terminus) | 1-15b | NLNSTIESLKTDIVS |

May be a fusion of gp36 and gp37.

Partial coiled-coil (identical to T4 coiled-coil) at beginning of sequence.

Sequences are aligned to maintain heptad registers and visually identified runs of identical amino acids.

With one exception (Aeh1 gene 2), all of the potential CCs are located near or at the C terminus of the protein. Of the segments with the highest probability of forming CCs in each sequence analyzed, 4 (SV14, T4, Tu1a, and Tu1b) are 200 to 250 aa upstream from the end of the protein, 3 (M1, Ox2, and T6) are 15 to 16 aa from the end, and the remaining 12 are located at the ends of the proteins. This grouping of CC locations is paralleled by closeness of sequence identity. SV14, T4, Tu1a, and Tu1b have identical CC sequences, as do M1, Ox2, and T6.

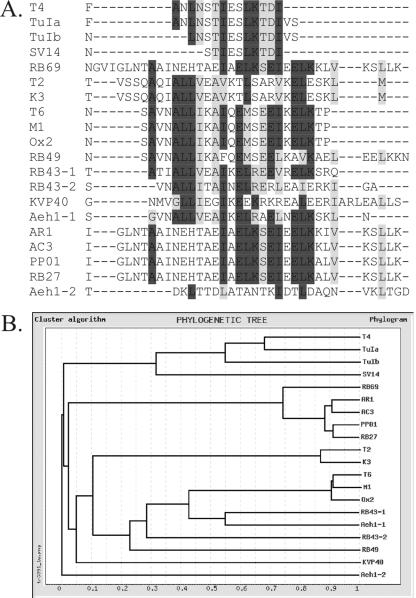

Finally, alignment of each protein sequence in the region with the highest probability of forming a CC was conducted using CLUSTAL W 1.75 on the GeneBee server. The resulting sequence alignment and phylogram diagrams are shown in Fig. 3. In general, these relationships parallel those seen in other phage genes, although there are a few exceptions (see below).

FIG. 3.

Alignment of coiled-coil sequences from gp37 (or proposed gp36-gp37 fusions). (A) Sequence alignment by CLUSTAL W. Dark shading identifies identical amino acids; light shading identifies similar amino acids. (B) Phylogenetic tree showing possible relatedness of leucine zippers.

DISCUSSION

Biological role of the gp37 CC.

It has been reported that the rod-like protein P37 is mainly a β-structured protein based on both experimental and theoretical evidence (1, 4, 7, 17, 26, 30). Bishop and Wood (2) isolated a suppressor of a gene 38 double amber mutation that obviates the need for the P38 chaperone at 30°C but not at 42°C. Snyder and Wood (32) found that it maps to a site near the transition between the thick upstream rod-like region and the thin downstream end (1, 7). Hashemolhosseini et al. (12) sequenced the region and found that the mutant included a 7-aa repeat. He suggests, “If association of two protein 37 monomers starts at this site, it would be conceivable that extending it provides an opportunity for spontaneous, albeit somewhat inefficient, dimerization.” However, there was no reference to the possibility of a CC. Cerritelli et al. (4), on the other hand, showed that the oligomeric segments P34, P36, and P37 are all homotrimeric and not homodimeric. In addition, they found that of the three, only gene 37 encodes a putative CC of 2.5 heptads. They localized it to about the same locus noted by Hashemolhosseini et al. Su et al. (33) showed the correlation between the lengths of dimeric CCs and their melting temperatures. The extension from two to three heptads can raise the melting temperature from almost nothing to the region of 20 to 50°C. Our contribution was to relate the suppressor effect of extending a putative CC motif to stabilizing the incipient origin of oligomerization by a CC “clamp.”

We hypothesized that by extending the CC one more heptad, we could stabilize the clamp to create a temperature-independent suppressor. This proved to be the case. The observed enhancement of temperature stability further supports the idea that the mechanism of P38 function is to enhance the parallel noncovalent association of the CC segments of gp37 monomers. This association leads to the formation of the trimeric CC and, we assume, to alignment of upstream and downstream regions leading to efficient maturation of the trimeric P37 TF segments. The assembly of P37 also requires P57A. P57A protein is also required for the maturation of P34 and P12 into trimers, even though no CC is apparent (4). Thus, gp34 and gp12 may have other means for the initiation of homotrimeric maturation. However, even in the absence of both P38 and P57A, T4 matures the various TF components to about 10% (8). The mechanism of initiation of maturation is still an unsolved problem.

In keeping with this proposed role for the CC in P37 maturation, we also examined 19 sequences of gp37 equivalents in other T-even-like bacteriophages whose sequences are known. All of the sequences contained one, two, or, in one protein, three potential CC segments that contain two to five putative CC heptads (Table 2). In 12 of the sequences, the segment with the highest probability was nearest to the C terminus of the protein.

The phylogenetic tree produced by aligning the CCs of the different phage species (Fig. 3B) is, in general, in agreement with those produced by other phage genes, notably genes 23, 18, and 19 (36). One exception is the identical sequences of the CCs of SV14 and T4; the other genes of these phage have only 84% identity, and morphology indicates significant divergence (36). Interestingly, while the sequences with the higher probability of forming CCs from each of the two RB43 genes are clearly related, the CC from the second Aeh1 gene (AAQ17987) appears to be unrelated to all of the other CCs. This finding agrees with the general model that has been proposed for modular swapping of phage genome segments by Sandmeier and others (29, 35).

The novel CCs (Table 1) allowed P37 assembly at temperatures up to 50°C. This finding raises the question of why T4 mutants possessing similar CC duplications (and that have lost gene 38 function) do not arise spontaneously. It seems advantageous for phage to minimize the number of chaperones needed for assembly. Three possibilities merit consideration. First, the extended CC may not be stable over multiple generations without the positive selection of a gp38 mutation. Because phage T4 uses homologous recombination to initiate replication during part of its life cycle (21), duplications may be quickly removed before sequence divergence or before a gp38 mutation can stabilize them. We did observe occasional heptad loss changing a pentaheptad to a tetraheptad. Second, a model of gene exchange between species of bacteriophage has been suggested (29, 35). Such an exchange at the very end of gene 37, which encodes the primary host ligand, would be of obvious advantage in expanding the phage host range. Deletion of the gene 38 chaperone, which is often found adjacent to gene 37 in bacteriophage species, might decrease the rate of exchange.

The third possibility derives from the role of the CC. Exact duplications in the CC could lead to misalignment of the CCs between the different monomers that make up the trimer. This misalignment might delay or even prevent proper P37 maturation. Interference with P37 maturation would lead to a reduction in the total number of properly assembled TFs and therefore lower numbers of progeny phage with sufficient TFs for infection. Thus, there may be selection for CCs that can align in only one register.

CCs as intrinsic chaperones.

While the precise mechanism in T4 LTF folding remains unclear, it is interesting that predictive algorithms such as MultiCoil predict dimeric and not trimeric CC regions based on protein sequence. However, since MultiCoil uses modeling based on homology to other known dimeric or trimeric proteins, two potential conclusions can be drawn. First, the TF's CC protein regions may in fact be trimeric and may simply contain sequences not recognizable as trimeric by the MultiCoil algorithm and its present structural database. Second, the CCs in the TF may not act to bring all three monomers together into a trimer but, instead, may be needed only to bring the first two together to stabilize the transient dimer until the third oligomer can associate and begin folding the highly stable trimer. Such transient dimer formation has been previously identified and investigated with model trimeric CC peptides (3, 6).

A critical step in the folding of many multicomponent fibrous proteins is the initial alignment of the monomeric proteins. Our results suggest that, in wild-type T4 phage, the folding of three copies of gp37 is initiated by a diheptad CC and the P38 chaperone (and possibly P57) but that phage with extended CCs are able to bypass P38 function at temperatures up to 50°C. CC structures have an alignment role in many proteins and can even promote folding of synthetic peptides and recombinant chimeric proteins (24, 27). We speculate that a CC, especially one designed to optimize the initiation of proper β-structural trimer formation, could, in a proper medium, stabilize the association of three gp37 molecules long enough for nonchaperoned trimer folding to occur. We believe that this scenario points to the feasibility of recombinant monomer production and simplified in vitro trimeric β-structure formation (16).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM58856 from the General Medical Sciences Institute. Support was also received from Nanoframes, Inc., for part of P. Hyman's later work on this project.

We thank Amy Keating for early discussions and help, Debabrata Raychaudhuri for ongoing helpful discussions, and Sankar Adhya for encouragement. We also thank N. Madias of Tufts University Medical School for supplementary support that enabled us to complete this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beckendorf, S. K. 1973. Structure of distal half of bacteriophage-T4 tail fiber. J. Mol. Biol. 73:37-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop, R. J., and W. B. Wood. 1976. Genetic analysis of T4 tail fiber assembly. I. A gene 37 mutation that allows bypass of gene 38 function. Virology 72:244-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boice, J. A., G. R. Dieckmann, W. F. DeGrado, and R. Fairman. 1996. Thermodynamic analysis of a designed three-stranded coiled coil. Biochemistry 35:14480-14485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerritelli, M. E., J. S. Wall, M. N. Simon, J. F. Conway, and A. C. Steven. 1996. Stoichiometry and domainal organization of the long tail-fiber of bacteriophage T4: a hinged viral adhesin. J. Mol. Biol. 260:767-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickson, R. C. 1973. Assembly of bacteriophage T4 tail fibers. IV. J. Mol. Biol. 79:633-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durr, E., and H. R. Bosshard. 2000. Folding of a three-stranded coiled coil. Protein Sci. 9:1410-1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earnshaw, W. C., E. B. Goldberg, and R. A. Crowther. 1979. The distal half of the tail fiber of bacteriophage T4. Rigidly linked domains and cross-beta structure. J. Mol. Biol. 132:101-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edgar, R. S., and I. Lielausis. 1965. Serological studies with mutants of phage T4D defective in genes determining tail fiber structure. Genetics 52:1187-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein, R. H., R. S. Edgar, M. Susman, C. M. Steinberg, A. Bolle, E. Kellenberger, G. H. Denhardt, I. Lielausis, E. Boydelat, and R. Chevalley. 1963. Physiological studies of conditional lethal mutants of bacteriophage T4D. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 28:375-392. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgopoulos, C. P., R. W. Hendrix, A. D. Kaiser, and W. B. Wood. 1972. Role of the host cell in bacteriophage morphogenesis: effects of a bacterial mutation on T4 head assembly. Nat. New Biol. 239:38-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg, E. 1983. Recognition, attachment and injection, p. 32-39. In C. K. Mathews, E. M. Kutter, G. Mosig, and P. B. Berget (ed.), Bacteriophage T4. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 12.Hashemolhosseini, S., D. Montag, L. Kramer, and U. Henning. 1994. Determinants of receptor specificity of coliphages of the T4 family: a chaperone alters the host range. J. Mol. Biol. 241:524-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashemolhosseini, S., Y.-D. Stierhof, I. Hindennach, and U. Henning. 1996. Characterization of the helper proteins for the assembly of tail fibers of coliphages T4 and λ. J. Bacteriol. 178:6258-6265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henning, U., and S. Hashemolhosseini. 1994. Receptor recognition by T-even-type coliphages, p. 291-298. In J. Karam et al. (ed.), Molecular biology of bacteriophage T4. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 15.Herrmann, R., and W. B. Wood. 1981. Assembly of bacteriophage T4 tail fibers: identification and characterization of the nonstructural protein gp57. Mol. Gen. Genet. 184:125-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyman, P., R. Valluzzi, and E. Goldberg. 2002. Design of protein struts for self-assembling nanoconstructs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:8488-8493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imada, S., and A. Tsugita. 1970. Morphogenesis of tail fiber of bacteriophage T4. II. Isolation and characterization of a component (the genes 35-36-37-38 directing half fiber). Mol. Gen. Genet. 109:338-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jozwik, C. E., and E. S. Miller. 1992. Regions of bacteriophage T4 and RB69 RegA translational repressor proteins that determine RNA-binding specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5053-5057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kells, S. S., and R. Haselkorn. 1974. Bacteriophage T4 short tail fibers are the product of gene 12. J. Mol. Biol. 83:473-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King, J., and W. B. Wood. 1969. Assembly of bacteriophage T4 tail fibers: sequence of gene product interaction. J. Mol. Biol. 39:583-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreuzer, K. N., and S. W. Morrical. 1994. Initiation of DNA replication, p. 28-48. In J. Karam et al. (ed.), Molecular biology of bacteriophage T4. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 22.Lupas, A., M. Van Dyke, and J. Stock. 1991. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252:1162-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsui, T., B. Griniuviené, E. B. Goldberg, A. Tsugita, N. Takana, and F. Arisaka. 1997. Isolation and characterization of a molecular chaperone, gp57A, of bacteriophage T4. J. Bacteriol. 179:1846-1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miroshnikov, K. A., E. I. Marusich, M. E. Cerritelli, N. Cheng, C. C. Hyde, A. C. Steven, and V. V. Mesyanzhinov. 1998. Engineering trimeric fibrous proteins based on bacteriophage T4 adhesins. Protein Eng. 11:329-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikolaev, V. K., A. M. Leontovich, V. A. Drachev, and L. I. Brodsky. 1997. Building multiple alignment using iterative dynamic improvement of the initial motif alignment. Biochemistry (Moscow) 62:578-582. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliver, D. B., and R. A. Crowther. 1981. DNA sequence of the tail fiber genes 36 and 37 of bacteriophage T4. J. Mol. Biol. 153:545-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandya, M. J., G. M. Spooner, M. Sunde, J. R. Thorpe, A. Rodger, and D. N. Woolfson. 2000. Sticky-end assembly of a designed peptide fiber provides insight into protein fibrillogenesis. Biochemistry 39:8728-8734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 29.Sandmeier, H. 1994. Acquisition and rearrangement of sequence motifs in the evolution of bacteriophage tail fibers. Mol. Microbiol. 12:343-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selivanov, N. A., S. I. Ven'iaminov, N. L. Golitsina, L. I. Nikolaeva, and V. V. Mesianzhinov. 1987. Structure and regulation of the assembly of bacteriophage T4 fibrillar proteins. I. Isolation and spectral properties of long fibers. Mol. Biol. (Engl. Transl. Mol. Biol. [Moscow]) 21:1258-1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon, L. D., J. G. Swan, and J. E. Flatgaard. 1970. Functional defects in T4 bacteriophages lacking the gene 11 and gene 2 products. Virology 41:77-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snyder, M., and W. B. Wood. 1989. Genetic definition of two functional elements in a bacteriophage T4 host-range “cassette.” Genetics 122:471-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su, J. Y., R. S. Hodges, and C. M. Kay. 1994. Effect of chain length on the formation and stability of synthetic alpha-helical coiled coils. Biochemistry 33:15501-15510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tabor, S., and C. C. Richardson. 1985. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:1074-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tetart, F., C. Desplats, and H. M. Krisch. 1998. Genome plasticity in the distal tail fiber locus of the T-even bacteriophage: recombination between conserved motifs swaps adhesin specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 282:543-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tétart, F., C. Desplats, M. Kutateladze, C. Monod, H.-W. Ackermann, and H. M. Krisch. 2001. Phylogeny of the major head and tail genes of the wide-ranging T4-type bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 183:358-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolf, E., P. S. Kim, and B. Berger. 1997. MultiCoil: a program for predicting two- and three-stranded coiled coils. Protein Sci. 6:1179-1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wood, W. B., F. A. Eiserling, and R. A. Crowther. 1994. Long tail fibers: genes, proteins, structure, and assembly. .In J. Karam et al. (ed.), Molecular biology of bacteriophage T4. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 40.Wood, W. B., R. S. Edgar, J. King, I. Lielausis, and M. Henniger. 1968. Bacteriophage assembly. Fed. Proc. 27:1160-1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]