Abstract

Introduction

Most women who give birth for the first time experience some form of perineal trauma. Second‐degree tears contribute to long‐term consequences for women and are a risk factor for occult anal sphincter injuries. The objective of this study was to evaluate a multifaceted midwifery intervention designed to reduce second‐degree tears among primiparous women.

Methods

An experimental cohort study where a multifaceted intervention consisting of 1) spontaneous pushing, 2) all birth positions with flexibility in the sacro‐iliac joints, and 3) a two‐step head‐to‐body delivery was compared with standard care. Crude and Adjusted OR (95% CI) were calculated between the intervention and the standard care group, for the various explanatory variables.

Results

A total of 597 primiparous women participated in the study, 296 in the intervention group and 301 in the standard care group. The prevalence of second‐degree tears was lower in the intervention group: [Adj. OR 0.53 (95% CI 0.33–0.84)]. A low prevalence of episiotomy was found in both groups (1.7 and 3.0%). The prevalence of epidural analgesia was 61.1 percent. Despite the high use of epidural analgesia, the midwives in the intervention group managed to use the intervention.

Conclusion

It is possible to reduce second‐degree tears among primiparous women with the use of a multifaceted midwifery intervention without increasing the prevalence of episiotomy. Furthermore, the intervention is possible to employ in larger maternity wards with midwives caring for women with both low‐ and high‐risk pregnancies.

Keywords: birth position, midwifery intervention, second‐degree tears, spontaneous pushing, two‐step delivery

The majority of women sustain some form of perineal trauma during childbirth 1 and primiparous women are more likely to suffer from severe injuries and second‐degree tears 1, 2. Since most research has focused on severe perineal trauma affecting the anal sphincter complex less attention has been paid to other types of perineal injuries. Significantly more women experience intense perineal pain after a second‐degree tear or an episiotomy compared with an intact perineum or a first‐degree tear 3, 4. Perineal and vaginal tears that involve muscles and the rectovaginal fascia contribute to sexual dysfunction 5, 6, and are associated with an increased risk of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse later in life 7, 8, and of rectocele in particular 9. Furthermore, injuries affecting the anal sphincter are sometimes wrongly classified as second‐degree tears and therefore not diagnosed and sutured correctly 10, 11. Finding ways to prevent second‐degree tears is of paramount importance.

A slow and controlled birth of the baby is thought to be of importance to prevent perineal trauma and midwives use different techniques to obtain the same. It has been hypothesized that spontaneous pushing will reduce perineal trauma 12, but as of yet there is no evidence for this 13, 14. However, none of the studies have compared directed versus spontaneous pushing during the active second stage when the baby is born.

The protective measures supported by evidence so far are the use of hot compresses, birthing the baby's head at the end of a contraction or between contractions, and avoidance of the lithotomy position for birth 15, 16, 17, 18. Despite this, the semi‐recumbent and the lithotomy position for birth are widely used in obstetric practice 17, 19.

Birth positions are often defined as either upright or supine 19. Alternatively they can be defined as flexible sacrum positions where weight is taken off the sacrum, thereby allowing the pelvic outlet to expand 20. Birth positions with flexibility in the sacro‐iliac joints are as follows: kneeling, standing, all‐fours, lateral position, and giving birth on the birth seat. Settings where the midwifery care includes spontaneous pushing and letting the woman choose her position for birth 21 have been associated with fewer perineal injuries 22, 23.

It might be suggested that a combination of techniques rather than one single technique would be effective in preventing perineal injuries. Hitherto, different midwifery methods such as spontaneous pushing, birth positions, and other preventive approaches have been evaluated in different study arms 15 but not in multifaceted interventions integrating several methods. Moreover, giving birth is a profound experience which carries significant meaning for the woman and her family 24. The intervention in this study is based on a theoretical framework of woman‐centered care which involves creating a reciprocal relationship with the woman through presence and participation during labor and birth 25, 26. This is facilitated in the intervention by the use of spontaneous pushing, flexible sacrum positions, and birthing the baby's head and body in two contractions.

The aim of this study was to evaluate a multifaceted intervention created to reduce second‐degree tears among primiparous women.

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study with an experimental design where an intervention is compared with standard care. The study was conducted at two maternity wards in Stockholm. Maternity ward 1 provides care to approximately 6,500 women/year whereas maternity ward 2 cares for approximately 4,100 women/year. Both wards provide care to women with low‐ and high‐risk pregnancies.

The primary outcome was perineal injuries, classified as second‐degree tears according to international standards 27, in addition using a new Swedish classification where vaginal tears with a measured depth of > 0.5 cm are considered second‐degree tears 28 because of the probability of a fascia defect. Secondary outcomes were the prevalence of no tear at all, severe perineal trauma affecting the anal sphincter complex, episiotomy, and the ability of the midwives in the intervention group to use the intervention.

Second‐degree tears are not registered in the national birth register in Sweden but examination of the local database of births for one of the maternity wards in this project revealed that 77 percent of the primiparous women had a vaginal and/or perineal injury, which is in line with previously reported prevalence 1, 29. A pretrial power calculation based on the assumption that the intervention would reduce second‐degree tears by 15 percent compared with standard care, indicated that at least 242 women were needed in each group to reach a statistical power of 80 percent at a 95 percent significance level (alpha). To ensure that enough participants were recruited to the study and taking dropouts into account, an additional 20 percent generated 291 women in each group.

The study included nulliparous Swedish‐speaking women, gestational age ≥ 37 + 0 weeks with spontaneous onset of labor or induction of labor. Cases of nulliparous women with diabetes mellitus (manifest or pregnancy‐induced), preterm birth ≤ 37 + 0, intrauterine growth restriction, female genital mutilation, multiple pregnancy, fetus in breech presentation, and stillbirths were excluded.

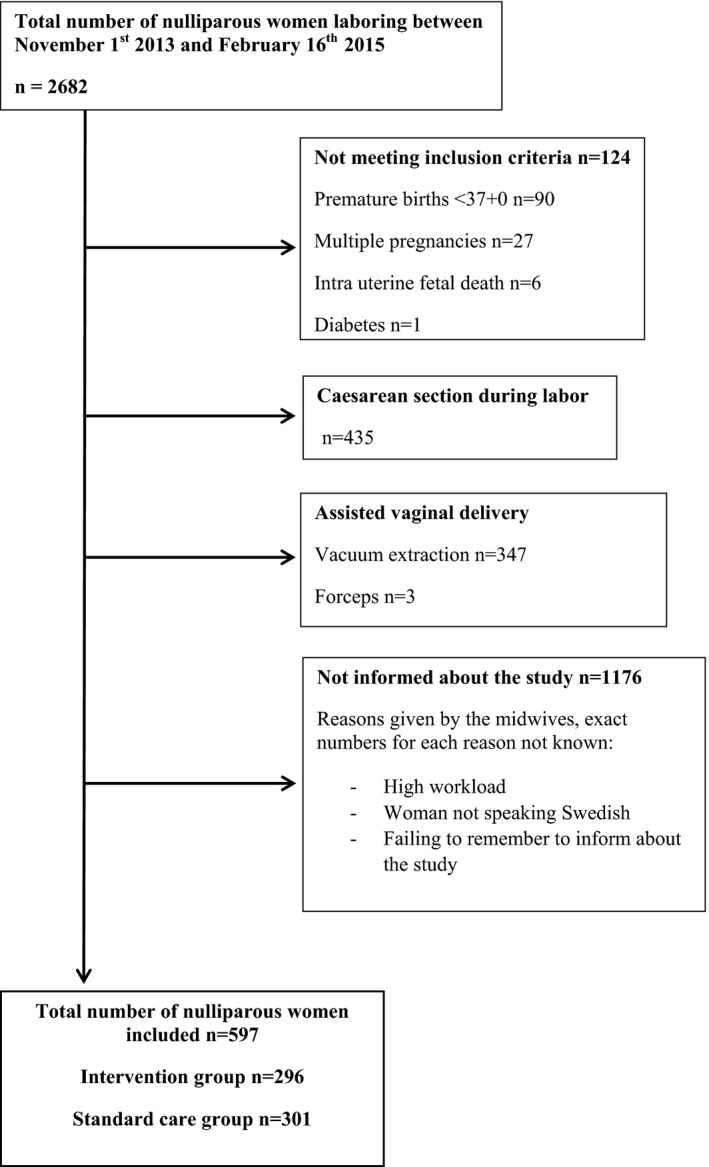

During the study period 1,773 nulliparous women fulfilled the study criteria (Fig. 1). The midwives were asked to write down their reasons for not including women in the study but most often forgot to do so. Reasons given for not asking women to participate were high workload, women not speaking Swedish (exclusion criterion), and failing to remember to ask women to participate.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the inclusion process in an intervention study to minimize second‐degree tears during labor, Stockhom, Sweden, 2013–2015.

The intervention is based on a theoretical framework of woman‐centered care 26 which consists of three parts (listed below) and is referred to as the MIMA model of care (an abbreviation for Midwives’ Management during the second stage of labor). The midwives in the intervention group were asked to use all three parts of the intervention during the second stage in all births they attended.

Spontaneous pushing: The woman feels a strong urge to push and follows the urge but does not put on any extra abdominal pressure. The midwife will if needed assist the woman to accomplish a controlled and slow birth of the baby by encouraging breathing and resisting the urge to push during the last contractions 30.

Flexible sacrum positions: Birth positions with flexibility in the sacro‐iliac joints, thereby enabling the pelvic outlet to expand (kneeling, standing, all‐fours, lateral position, and giving birth on the birth seat) 20.

Using the two‐step principle of head‐to‐body birthing technique if possible 18. With this technique, the head is born at the end of a contraction or between contractions and the shoulders are born with the next contraction.

Standard care during the second stage of labor is sparsely recorded by midwives in Sweden and there are no national guidelines about birth position, pushing methods, or whether certain methods of manual perineal protection should be performed. Hence, the management of the second stage of labor depends on the assisting midwife's experience, knowledge, and preferences. The assumption derived from reviewing research and clinical experience is that standard care for primiparous women consists mostly of directed pushing and semi‐recumbent birth positions 17. Furthermore, midwives often prefer to assist the woman to birth the baby's head and shoulders in one contraction because of fear of endangering the child 31.

Implementation of the Study

Educational sessions with all midwives on how to measure the tears and how to complete the study protocol were held before the start of the study. After this initial phase, midwives were recruited to the intervention group and had further training on how to perform the intervention. To avoid contamination between the groups and dilution of the intervention, midwives working day shift at one maternity ward were asked to perform the intervention and midwives working night shift asked to continue with standard care. In the other ward this was reversed. In maternity ward 1, 76 percent (35/46) of the midwives working day shift agreed to participate in the intervention group, whereas in maternity ward 2, 85 percent (17/20) of the midwives working night shift agreed to participate. Midwives in the standard care group received no additional information.

Data Collection

The data collection lasted from November 1, 2013 to June 16, 2014 in maternity ward 1, and from April 7, 2014 to February 16, 2015 in maternity ward 2. Women who met the inclusion criteria were asked to participate in the study when admitted to the maternity ward. They received information about the study, but were blinded as to whether they received the intervention or not. This was considered possible since none of the parts of the intervention are new in midwifery care. Midwives in both groups measured the perineum and the tear after the birth together with a colleague (midwife, obstetrician, or auxiliary nurse) with a sterile measure stick marked in centimeters.

The midwives completed a study protocol containing questions about labor variables and midwifery techniques used during birth. The variables documented in the protocol were as follows: time when the woman was fully dilated, the use of oxytocin, pushing technique, presentation, different methods of perineal protection, the use of hot compresses, oil/lubricant, digital stretching, surveillance of the perineum, birth position, concerns about fetal health, and whether the two‐step principle of head‐to‐body birth was practiced or not. The measurements of the tears were further classified by the first author as no tear, labial tear only, first‐degree tear, second‐degree tear, and severe perineal trauma affecting the anal sphincter complex. Vaginal tears with a depth of < 0.5 cm were classified as first‐degree tears and vaginal tears with a depth of > 0.5 cm were classified as second‐degree tears since they are likely to involve the rectovaginal fascia, an important support structure between the vaginal wall and the rectum 9. The measurements together with descriptions of the tear and follow‐up questions in the protocol about assessment and suturing of the tear made the classification possible (Table 4). To ensure the validity of the classifications, meetings were held with two uro‐gynecologists to discuss a selected number of protocols.

The following variables were retrieved from the hospitals local database: age, marital status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), assisted pregnancy and psychiatric illness, pain relief, time of labor onset, time when active second stage started, time when the baby was born, postpartum bleeding, and assessment of the tear at discharge. Variables retrieved regarding the baby were birthweight, head circumference, and Apgar scores. As the health‐related problems were so uncommon in both groups they were turned into a composite variable including all health‐related problems (Table 1). Continuous variables categorized were: age (< 25 years, 25–35 years, > 35 years), BMI (< 18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, > 30), and postpartum bleeding (< 500 mL, 500–1,000 mL, > 1,000 mL).

Table 1.

Socio‐Demographic Characteristics of Women Participating in an Intervention Study to Minimize Second‐Degree Tears during Labor, Stockholm, Sweden, 2013–2015

| Intervention group | Standard care group | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 296 | N = 301 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age groups (years) | ||

| < 25 | 65 (22.0) | 40 (13.3)b |

| 25–35 | 208 (70.5) | 232 (77.3) |

| > 35 | 22 (7.5) | 28 (9.3) |

| Married/cohabiting | 263 (98.5) | 253 (98.8) |

| Tobacco use | 13 (4.7) | 3 (1.1)b |

| BMI groups | ||

| < 18.5 | 9 (3.3) | 14 (5.0) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 199 (72.1) | 218 (77.9) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 56 (20.3) | 35 (12.5)b |

| > 30.0 | 12 (4.3) | 13 (4.6) |

| Health‐related problems before/during pregnancya | 31 (11.0) | 35 (12.2) |

| Assisted pregnancy (IVF/ICSI) | 17 (5.8) | 14 (4.7) |

| Psychiatric problems (anxiety, depression, etc.) | 25 (8.4) | 35 (11.6) |

Composite variable including asthma, thrombosis, chronic kidney disease, endocrine diseases, diabetes, epilepsy, chronic hypertension.

p < 0.05.

Time variables were calculated between time of birth and the start of the passive second stage, and time of birth and the start of the active second stage. Passive second stage was categorized into the following: <1 hour, 1–2 hours, and > 2 hours, and active second stage into: < 30 minutes, 30–60 minutes, and > 60 minutes. Birth positions were dichotomized into flexible and nonflexible sacrum positions. Pushing methods, surveillance of the perineum, and concerns about fetal health were dichotomized. A variable was created to analyze the primary outcome in which second‐degree tears were compared with minor injuries including no tear, labial tears, and first‐degree tears. The three parts of the intervention were analyzed both separately and as a composite variable (MIMA model of care). This variable includes the cases where the midwives were able to perform all parts of the intervention during the entire active second stage.

Statistical Methods and Analysis

The data were analyzed according to intention‐to‐treat analysis and descriptive statistics were used to present the data. Crude and Adjusted Odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval were calculated between women who received the intervention and those who received standard care, for the various explanatory variables. To study any association between the primary outcome (second‐degree tears) and the identified risk factors, a stepwise multivariate regression modeling was performed. First, all statistically significant variables from the univariate analysis were entered one by one (age, BMI, and midwives’ working experience). Thereafter, previously known risk factors for perineal trauma (birthweight > 4,000 g, use of oxytocin, and the length of the active second stage) were entered. The IBM SPSS software package version 22.0 was used for the data analysis. The study was approved by the Ethics committee in Stockholm no. 2013/859‐3/2.

Results

In this intervention study, a total of 597 nulliparous women participated: 296 in the intervention group and 301 in the standard care group. The two groups of women were fairly well balanced except that women in the intervention group were slightly younger and had a higher BMI (Table 1) and there were no differences with regard to obstetric variables such as labor onset, augmentation with oxytocin, and epidural analgesia, which was 61.1 percent in both groups (Table 2). The duration of the passive second stage differed between the groups, and was significantly shorter for the women in the intervention group. However, the majority of the women gave birth within 2 hours in both groups and there were no differences about the active second stage of labor. The Apgar scores did not differ between the groups and there were no babies with an Apgar score of < 5 at 5 minutes.

Table 2.

Obstetric and Birth Characteristics of Women Participating in an Intervention Study to Minimize Second‐Degree Tears during Labor, Stockholm, Sweden, 2013–2015

| Intervention group | Standard care group | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 296 | N = 301 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Induction of labor | 41 (13.9) | 48 (15.9) |

| Pain relief† | ||

| Immersion in water/shower | 63 (21.4) | 56 (18.7) |

| Acupuncture | 25 (8.5) | 29 (9.7) |

| Sterile water injections | 17 (5.8) | 20 (6.7) |

| Nitrous oxide | 247 (83.7) | 260 (86.7) |

| Epidural analgesia | 181 (61.1) | 184 (61.1) |

| Pudendal nerve block | 19 (6.4) | 24 (8.0) |

| Augmentation with oxytocin during labor | 162 (55.1) | 178 (59.1) |

| Passive second stage | ||

| < 1 hours | 127 (46.0) | 146 (50.9) |

| 1–2 hours | 84 (30.4) | 61 (21.6)* |

| > 2 hours | 65 (23.6) | 79 (27.5) |

| Active second stage | ||

| < 30 minutes | 149 (51.9) | 154 (52.0) |

| 30–60 minutes | 103 (35.9) | 107 (36.1) |

| > 60 minutes | 35 (11.9) | 35 (11.8) |

| Midwife concerned about fetal‡ health | 88 (29.8) | 73 (24.3) |

| Birth position | ||

| Sitting | 53 (18.0) | 80 (26.7) |

| Kneeling | 33 (11.2) | 23 (7.7)* |

| Lateral | 61 (20.7) | 56 (18.7) |

| All‐fours | 20 (6.8) | 11 (3.7)* |

| Lithotomy/recumbent | 41 (13.9) | 45 (15.0) |

| Birth chair/squatting | 87 (29.5) | 85 (28.3) |

| Presentation | ||

| Occiput anterior | 289 (98.0) | 287 (95.7) |

| Occiput posterior | 6 (2.0) | 13 (4.3) |

| Birth weight, g (mean) | 3,482 | 3,521 |

| Head circumference, cm (mean) | 34.7 | 34.8 |

†Ref = Women not exposed to the variable being studied. ‡The midwife had worries regarding the baby's heartbeat/electronic fetal monitoring tracings during the second stage. * p < 0.05.

The working experience of the midwives differed between the groups. The group that performed standard care consisted of more newly qualified midwives, 41 percent compared with 23.1 percent, and there were more experienced midwives (> 10 years) in the intervention group, 38.7 percent versus 27.8 percent (p ≤ 0.001).

The midwives in the intervention group used the techniques included in the MIMA model of care to a significantly greater extent than those in the control group even if spontaneous pushing, flexible sacrum positions, and the two‐step head‐to‐body birthing technique were also used in the standard care group (Table 3). When all of the three different parts of the MIMA model of care were assessed as a composite variable this combined approach was only used by 5.7 percent in the standard care group compared with 18.0 percent (p ≤ 0.001) in the intervention group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Components of the MIMA Model of Care Used by the Midwives’ in an Intervention Study to Minimize Second‐Degree Tears during Labor, Stockholm, Sweden, 2013–2015

| Intervention group | Standard care group | Crude OR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 296 (%) | N = 301 (%) | (95% CI) | |

| Components and composite variable for the MIMA model of care | |||

| Spontaneous pushing | 122 (41.6) | 94 (31.2) | 1.57 (1.12–2.20)* |

| Flexible sacrum position | 202 (68.2) | 175 (58.3) | 1.55 (1.11–2.16)* |

| Two‐step principle of head‐to‐body birth | 142 (48.5) | 97 (32.9) | 1.92 (1.38–2.68)** |

| The MIMA model of care† | 53 (18.0) | 17 (5.7) | 3.65 (2.06–6.46)** |

†The MIMA model of care is a composite variable of the use of all the three parts of the intervention during the entire second stage. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001.

Other midwifery techniques during the active second stage, such as digital stretching of the perineum and directed pushing, were not used as frequently in the intervention group as in the control group. All the midwives in this study performed manual perineal protection in some form, but the methods used varied (Table 4) and did not affect the outcome.

Table 4.

Care of the Perineum and Manual Support Techniques Used by the Midwives’ in an Intervention Study to Minimize Second‐Degree Tears during Labor, Stockholm, Sweden, 2013–2015

| Intervention group | Standard care group | Crude OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 296 (%) | N = 300 (%) | ||

| Care of the perineum | |||

| Good surveillance of the perineum | 231 (79.7) | 225 (75.5) | 1.28 (0.86–1.88) |

| Warm compresses on the perineum | 251 (92.6) | 265 (91.1) | 1.24 (0.67–2.27) |

| Massaging the vagina and perineum with lubricant or oil | 114 (41.9) | 135 (46.4) | 0.83 (0.60–1.16) |

| Manual stretching of the perineum | 41 (15.1) | 86 (29.6) | 0.42 (0.28–0.64)** |

| Manual perineal support‡ | |||

| Manual perineal support | 178 (61.0) | 146 (47.5) | 0.71 (0.51–0.98)* |

| One hand on the baby's head | 94 (32.2) | 53 (18.0) | 2.17 (1.47–3.19)** |

| Ritgens maneuver† | 28 (9.6) | 24 (8.1) | 1.20 (0.68–2.12) |

| Supporting the birth of the shoulders | 154 (52.7) | 148 (50.2) | 1.11 (0.80–1.53) |

†Ritgens maneuver = The fetal chin is reached for between the anus and the coccyx and pulled anteriorly, while using the fingers of the other hand on the fetal occiput to control speed of delivery and keep flexion of the fetal neck.‡ ‡Ref = Women not exposed to the variable being studied. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

The percentage of women in the intervention group who suffered a second‐degree tear (70.7%) was lower than in the standard care group (78.3%) (Table 5). The prevalence of episiotomies was low in both groups (1.7 and 3.0%) and the prevalence of severe perineal trauma affecting the anal sphincter muscles did not differ significantly between the two groups (3.7 and 4.7%). The factors included in the stepwise logistic regression model did not alter the protectiveness of the intervention (Adj. OR 0.53 [95% CI 0.33–0.84]) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Perineal Tears and Postpartum Bleeding of Women Participating in an Intervention Study to Minimize Second‐Degree Tears during Labor, Stockholm, Sweden, 2013–2015

| Intervention group | Standard care group | Adjusted OR† (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 296 (%) | N = 301 (%) | ||

| Perineal trauma | |||

| Second‐degree tear (primary outcome) | 208 (70.7) | 234 (78.3) | 0.53 (0.33–0.84)* |

| Minor injury (no tear, labia, first degree) | 75 (25.5) | 51 (17.1) | |

| Assessment of tear at discharge | |||

| Sore/swollen | 13 (4.4) | 16 (5.3) | NA |

| Hematoma | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | NA |

| Postpartum bleeding | |||

| < 500 mL | 219 (76.3) | 218 (75.5) | 0.90 (0.59–1.39) |

| 500–1,000 mL | 58 (20.3) | 60 (20.8) | 1.18 (0.74–1.86) |

| > 1,000 mL | 10 (3.5) | 11 (3.8) | NA |

†Adjusted for midwives' working experience, age, BMI, birthweight > 4,000 g, augmentation with oxytocin, and active second stage. NA = not applicable. * p < 0.05.

Discussion

The use of the MIMA model of care reduced the prevalence of second‐degree tears among primiparous women in this study. This is important for women as perineal and vaginal tears are associated with dyspareunia 5, lower levels of vaginal arousal and orgasm 6, and pelvic organ prolapse later in life 7, 8, all factors that have an influence on women's quality of life.

An important finding in this study is the low prevalence of episiotomy in both groups and in the intervention group in particular. Since an episiotomy involves the same perineal muscles as a second‐degree tear 32, an increased prevalence of episiotomy would counteract the reduction in second‐degree tears seen in this study. Furthermore, there is a consensus that a restrictive episiotomy policy is beneficial to women 33. Many obstetric units in the Nordic countries have introduced a multifactorial protective intervention developed in Finland to reduce severe perineal trauma 34. The MIMA model of care and the Finnish intervention are both multifaceted interventions based on the same assumption: that a slow expulsion of the baby's head will protect the woman from tearing during birth. However, the Finnish intervention differs from the MIMA model as it focuses on the use of a specific hands‐on perineal protection technique, and recommends episiotomy if indicated 30. One of the concerns raised about the Finnish intervention is the increased prevalence of episiotomies at the maternity wards where the intervention is employed 34.

The midwives in the intervention group used all parts of the intervention to a greater extent than the midwives in the standard care group but total use of the intervention during the entire active second stage may be considered as low. Even though most of the midwives agreed to participate in the intervention group many of them voiced concerns, particularly their fear of endangering the baby if the two‐step head‐to‐body birthing technique were to be used 31. The midwives associated the different parts of the intervention with practices used in the home birth setting 35 where no medical pain relief is available. Some of them questioned whether it was possible to facilitate spontaneous pushing in a setting where most nulliparous women use epidural analgesia for pain relief. One barrier reported to affect adherence to interventions is lack of applicability because of the clinical situation—in this case, the high use of epidurals 36. Research about implementation shows that using local opinion leaders and feedback helps to improve performance 37. Reflective meetings were held with the midwives in the intervention group but in retrospect, identification and extended education of local opinion leaders could have helped the midwives deal with what they perceived as difficult.

When comparing the working experience of the two groups, it turned out that the midwives in the intervention group were more experienced on average than those in the control group. It is not known if longer working experience of a midwife is a protective factor for perineal trauma. Results from a recent study suggest that the midwife's individual performance is a predictive factor for the occurrence of second‐degree tears but unfortunately the study does not report on working experience 38. It could be argued that an experienced midwife would be more able to prevent perineal trauma but this need not be so given that longer experience in previous practice is a known barrier to adherence 39, possibly making experienced midwives less receptive to new concepts or guidelines. However, adjusting for the differences in working experience did not alter the protectiveness of the intervention.

The experimental design, the detailed study protocol with midwifery measures during the second stage of birth, and the measuring of the tear after birth are the major strengths of this study. The study design also deals with the problem of contamination and dilution of the intervention when performed by midwives at the same maternity ward, and the possibility of different working cultures between midwives working day or night shift. Furthermore, the MIMA model of care is multifaceted and takes into account the fact that women's expectations, wishes, and labors may differ, thus enabling the midwife to provide woman‐centered care 26.

While a reduced prevalence of second‐degree tears was observed in this study, a causal relationship between the MIMA model of care and the prevention of tears cannot be established since this is an experimental study with a potential risk of bias. Not all eligible nulliparous women were recruited to the study. However, both the intervention and the standard care group were similar with regard to labor onset and obstetric variables, and the differences in maternal characteristics were adjusted for in the final analysis.

Another limitation is that it was not possible to perform an extensive analysis of the women not included in the study since the primary outcome and the midwifery techniques used during labor and birth are not registered in the database. Ethical regulations restrict the possibility of retrieving data from individual records on women not enrolled in the study. Furthermore, ethnicity is not registered in the registers of birth and therefore it is not possible to analyze any effect of ethnicity. However, the most common countries of birth for female Swedish citizens born outside Sweden are presently Finland, Poland, Iran, and Syria 40, and to the best of our knowledge none of the groups from these countries are considered to be at higher risk of suffering perineal trauma.

Given the limitations of the study, the results should be interpreted with some caution. To further establish the effectiveness of the MIMA model of care it should be evaluated in a randomized cluster trial, including maternity wards of different sizes and in rural and urban areas.

Conclusion

The use of the MIMA model of care reduced the incidence of second‐degree tears among primiparous women. The intervention does not seem to cause any harm as it does not increase severe perineal trauma or unwanted interventions such as episiotomy. Nor does it restrict women's choice of position for birth. Furthermore, the intervention is possible to use in larger maternity wards with midwives caring for women with both low‐ and high‐risk pregnancies.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The Sahlgrenska Academy is the employer of the first author's position as a PhD student. Otherwise there is no funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the women and midwives who participated in the study. We would also like to thank Professor Max Petzold at the University of Gothenburg for valuable input about statistical matters.

(Birth 44: 1 March 2017)

The copyright line for this article was changed on 25 January 2017 after original online publication.

References

- 1. Samuelsson E, Ladfors L, Lindblom BG, Hagberg H. A prospective observational study on tears during vaginal delivery: Occurrences and risk factors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2002;81(1):44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Leeuw JW, Struijk PC, Vierhout ME, Wallenburg HC. Risk factors for third degree perineal ruptures during delivery. BJOG 2001;108(4):383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andrews V, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Jones PW. Evaluation of postpartum perineal pain and dyspareunia–A prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;137(2):152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dannecker C, Hillemanns P, Strauss A, et al. Episiotomy and perineal tears presumed to be imminent: Randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2004;83(4):364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Radestad I, Olsson A, Nissen E, Rubertsson C. Tears in the vagina, perineum, sphincter ani, and rectum and first sexual intercourse after childbirth: A nationwide follow‐up. Birth (Berkeley, Calif) 2008;35(2):98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rathfisch G, Dikencik BK, Kizilkaya Beji N. Effects of perineal trauma on postpartum sexual function. J Adv Nurs 2010;66(12):2640–2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tegerstedt G, Miedel A, Maehle‐Schmidt M, et al. Obstetric risk factors for symptomatic prolapse: A population‐based approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194(1):75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rodriguez‐Mias NL, Martinez‐Franco E, Aguado J, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence, do they share the same risk factors? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2015;190:52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beck DE, Allen NL. Rectocele. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2010;23(2):90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corton MM, McIntire DD, Twickler DM, et al. Endoanal ultrasound for detection of sphincter defects following childbirth. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24(4):627–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW. Occult anal sphincter injuries\xF6Myth or reality? BJOG 2006;113(2):195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sampselle CM, Hines S. Spontaneous pushing during birth. Relationship to perineal outcomes. J Nurse Midwifery 1999;44(1):36–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prins M, Boxem J, Lucas C, Hutton E. Effect of spontaneous pushing versus Valsalva pushing in the second stage of labour on mother and fetus: A systematic review of randomised trials. BJOG 2011;118(6):662–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lemos A, Amorim MM, deDornelas Andrade A , et al. Pushing/bearing down methods for the second stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;10:Cd009124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aasheim V, Nilsen AB, Lukasse M, Reinar LM. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;12:Cd006672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gottvall K, Allebeck P, Ekeus C. Risk factors for anal sphincter tears: The importance of maternal position at birth. BJOG 2007;114(10):1266–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Elvander C, Ahlberg M, Thies‐Lagergren L, et al. Birth position and obstetric anal sphincter injury: A population‐based study of 113 000 spontaneous births. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Albers LL, Sedler KD, Bedrick EJ, et al. Midwifery care measures in the second stage of labor and reduction of genital tract trauma at birth: A randomized trial. J Midwifery Womens Health 2005;50(5):365–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gupta JK, Hofmeyr GJ, Shehmar M. Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;5:Cd002006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kemp E, Kingswood CJ, Kibuka M, Thornton JG. Position in the second stage of labour for women with epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;1:Cd008070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lindgren HE, Brink A, Klinberg‐Allvin M. Fear causes tears—Perineal injuries in home birth settings. A Swedish interview study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011;11:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McPherson KC, Beggs AD, Sultan AH, Thakar R. Can the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIs) be predicted using a risk‐scoring system? BMC Res Notes 2014;7:471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hutton EK, Cappelletti A, Reitsma AH, et al. Outcomes associated with planned place of birth among women with low‐risk pregnancies. CMAJ 2016;188(5):E80–E90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Larkin P, Begley CM, Devane D. Women's experiences of labour and birth: An evolutionary concept analysis. Midwifery 2009;25(2):e49–e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hunter LP. Being with woman: A guiding concept for the care of laboring women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2002;31(6):650–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berg M, Asta Olafsdottir O, Lundgren I. A midwifery model of woman‐centred childbirth care\xF6In Swedish and Icelandic settings. Sexual Reprod Healthcare: Official J Swedish Assoc Midwives 2012;3(2):79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fernando RJ, Sultan AH, Freeman RM, Adams EJ. The Management of Third‐ and Fourth‐Degree Perineal Tears. 2015. Accessed August 1, 2016. Available at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-29.pdf.

- 28. Olsson A. Perineal trauma and suturing In: Lindgren H, Christensson K, Dykes A‐K, eds. Reproductive Health: The Midwife's Core Competencencies. Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2016:512. [Google Scholar]

- 29. McCandlish R, Bowler U, van Asten H, et al. A randomised controlled trial of care of the perineum during second stage of normal labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105(12):1262–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Laine K, Pirhonen T, Rolland R, Pirhonen J. Decreasing the incidence of anal sphincter tears during delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111(5):1053–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kotaska A, Campbell K. Two‐step delivery may avoid shoulder dystocia: Head‐to‐body delivery interval is less important than we think. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2014;36(8):716–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sultan AH, Fenner DE, Thakar R. Perineal and Anal Sphincter Trauma [electronic resource] Diagnosis and Clinical Management. London: Springer‐Verlag London Limited, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;1:Cd000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Poulsen MO, Madsen ML, Skriver‐Moller AC, Overgaard C. Does the Finnish intervention prevent obstetric anal sphincter injuries? A systematic review of the literature. BMJ Open 2015;5(9):e008346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Priddis H, Dahlen H, Schmied V. What are the facilitators, inhibitors, and implications of birth positioning? A review of the literature. Women Birth 2012;25(3):100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gravel K, Legare F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision‐making in clinical practice: A systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Implementation Science: IS 2006;1:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, et al. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci 2012;7(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ott J, Gritsch E, Pils S, et al. A retrospective study on perineal lacerations in vaginal delivery and the individual performance of experienced midwives. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? JAMA 1999;282(15):1458–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Statistics Sweden. Finland and Iraq—The most common countries of birth among citizens born outside Sweden . 2016. Accessed August 1, 2016. Available at: http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Artiklar/Finland-och-Irak-de-tva-vanligaste-fodelselanderna-bland-utrikes-fodda/2016.