Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has been associated with reduced orienting to social stimuli such as eyes, but the results are inconsistent. It is not known whether atypicalities in phasic alerting could play a role in putative altered social orienting in ASD. Here, we show that in unisensory (visual) trials, children with ASD are slower to orient to eyes (among distractors) than controls matched for age, sex, and nonverbal IQ. However, in another condition where a brief spatially nonpredictive sound was presented just before the visual targets, this group effect was reversed. Our results indicate that orienting to social versus nonsocial stimuli is differently modulated by phasic alerting mechanisms in young children with ASD. Autism Res 2017, 10: 246–250. © 2016 The Authors Autism Research published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on behalf of International Society for Autism Research.

Keywords: Autism, social orienting, eye tracking, phasic alerting, arousal, face perception

According to social orienting theories of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), people with this condition orient less or slower to socially salient stimuli than people with typical development (TD; Dawson et al., 2004). Further, it is assumed that reduced orienting early in life may have cascading effects on both brain development, cognition and behavior (Dawson et al., 2004; Schultz, 2005). In line with this view, studies have demonstrated that children with ASD orient less to some socially relevant stimuli such as hand claps and voices calling their names (Dawson et al., 2004; Hirstein, Iversen, & Ramachandran, 2001). However, studies using face‐like stimuli provide a mixed picture of both typical (Shah, Gaule, Bird, & Cook, 2013), and slower (Guillon et al., 2016) orienting in ASD, leading some to question the validity of the social orienting hypothesis of ASD (Johnson, Senju &Tomalski,, 2015).

ASD has also been linked to atypical functioning of the phasic alerting system, which is anatomically and functionally partly dissociable from the visuo‐spatial orienting brain network. Alerting mechanisms are responsible for achieving and maintaining an adaptive level of arousal to incoming sensory information (Petersen & Posner, 2012; Robertson & Caravan, 2004; Robertson, Mattingley, Rorden, & Driver, 1998). A phasic alerting response occurs when the level of arousal increases after a sensory cue unrelated to the task (Petersen & Posner, 2012). In contrast to visuo‐spatial attention, phasic alerting does not direct attention to specific spatial locations. Phasic alerting cues can hasten responses of the visual system and enhance perceptual accuracy (Brown et al., 2015; Keetels & Vroomen, 2011; Zou, Müller, & Shi, 2012). Tonic and phasic firing rates of arousal‐related neurotransmitter systems, most notably the noradrenergic system, are believed to underlie this effect (Petersen & Posner, 2012). The largest benefits of phasic alerting on visual attention may be seen in people with attenuated tonic alertness due to clinical conditions such as right hemisphere neglect (Robertson et al., 1998) or pharmacological manipulations of the adrenergic system (Brown et al., 2015). People with ASD have been shown to respond atypically to sudden and unexpected information from unattended modalities (Keehn, Nair, Lincoln, Townsend, & Müller, 2016; Orekhova & Stroganova, 2014). In addition to these domain general findings, atypical autonomic responses to social stimuli such as eyes with direct gaze have been found in ASD (Dalton et al., 2005; Kylliäinen & Hietanen, 2006). Although it has been hypothesized that that atypical phasic alertingould be contributing to atypical visuo‐spatial attention processes in ASD (Orekhova & Stroganova, 2014), to our knowledge, no study has investigated the role of phasic alerting for social orienting in children with ASD. In the current study, we showed children with ASD and controls visual stimuli displaying human eyes among several distractor objects. Eyes are one of most salient stimuli for humans from infancy and onwards (Johnson et al., 2015). The first aim of the study was to test a prediction derived from the social orienting hypothesis; namely that one would see slower orienting to the eyes in the ASD than in the TD group. To our knowledge, no previous study has tested orienting to eyes, specifically (i.e., not presented in the context of a whole face). A second aim of the study was to examine orienting to social stimuli (eyes) under different levels of alertness. To manipulate alertness, the visual stimuli were preceded by either no sound or a brief spatially non‐informative sound. In light of previous findings of altered arousal related processes in ASD and the fact that arousal has strong effects on cognitive processing, we hypothesized that children with ASD to be differently affected by phasic alerting than the TD group. We included both social and non‐social sounds as alerting stimuli, in order to be able to explore whether the type of altering stimuli would play a role in this context.

Methods

Sixteen children with ASD (mean age: 6.5 years; 3 female) participated in the experiment. All children were recruited from a habilitation center and had a community diagnosis of ASD. Diagnosis was independently confirmed by assessment with the ADOS‐2 (15 children) or by records from medical assessment including the ADOS‐2 (one child). The ASD group was compared to a typically developing (TD) control group (N = 16; mean age: 6.5 years 2 female). All participants were assessed with either the WISC‐IV (N = 9) (Wechsler, 2003) or the WPPSI‐III (N = 23) (Wechsler, 2002). Nonverbal IQ (NVIQ) was calculated according to a previous study (Black, Wallace, Sokoloff, & Kenworthy, 2009). An initial group of TD participants (N = 24) was recruited from a database of families volunteering to participate in developmental research. For each child with ASD, we selected the child with TD that was closest in NVIQ as a matched control. Groups did not differ in age (P > .30) or NVIQ (P > .18). Descriptive statistics from children included in the final analysis (after exclusion of one outlier, see Analysis and Data reducition) are shown in Table 1. Children with TD had no psychiatric or medical diagnosis, according to parent report, and did not show clinical signs of ASD as assessed by the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS; Constantino & Gruber, 2002; all T‐scores < 60).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (Means and Standard Deviations)

| Measure | ASD (N = 15) | TD (N = 16) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 80 (20) | 79 (12) |

| NVIQ | 100 (26) | 115 (18) |

| SRS total score | 80 (16) | 44 (5) |

| ADOS‐2 total score* | 14 (6) | – |

| ADOS‐2 Social Affect subscale* | 11 (6) | |

| ADOS‐2 Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors subscale* | 3 (2) | |

| Total number of rejected trials | 0.87 (1.2) | 0.69 (1.01) |

Note. Based on 14 children

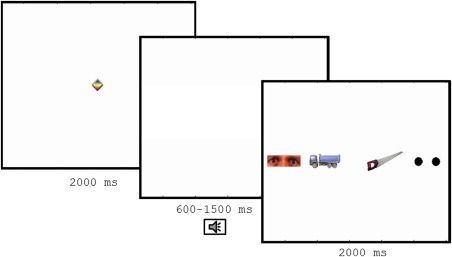

We presented images of human eyes with direct gaze along with three nonsocial images (see Fig. 1) on a computer screen. Nonsocial images depicted two everyday objects and a pair of two black circles resembling the low‐level visual features of human pupils. In total, 12 nonsocial objects and eye regions from four faces were used as stimuli. Eye regions from a validated stimulus set (Lundqvist, Flykt, & Öhman, 1998) were used as stimuli. We used eyes from faces displaying fear to maximize the likelihood of orienting (Whalen et al., 2004). The stimuli were presented in randomized order and were preceded by a moving animation in order to draw participants' attention to the center of the screen. On unisensory trials, the images were presented without any accompanying sound. On multisensory trials, the images were preceded by a phasic alerting signal starting within a variable time interval of 500–700 milliseconds (ms) before the onset of the visual stimuli. The alerting signal could be either a single phoneme (social multisensory trials) or a brief beep (nonsocial multisensory trials). Auditory stimuli had an approximate sound volume of 75 decibels and aduration of 300–450 ms.

Figure 1.

Outline of the experiment. All trials started with by a moving animation followed by a blank screen. A sound (either social or nonsocial) or no sound was presented during this interval. After this, a stimulus array with two eyes and three nonsocial objects were shown. The position of the objects was counterbalanced across trials.

The eyes were equally likely to appear in all positions. However, due to a technical error, one of four nonsocial multisensory trials was lacking for all participants. To correct for this, we analyzed only the three first trials within each condition (resulting in a total of nine trials per participant). Saccade latency was measured with a Tobii TX120 (Tobii Inc, Danderyd, Sweden) eye tracker at a sample rate of 60 HZ. The study was approved by the regional research ethics committee of Stockholm. Children were asked to attend to the screen, but were given no further instructions.

Analysis and Data Reduction

The dependent variable was the mean latency in ms to the first fixation at the eyes in the stimulus arrays. Trials were discarded if participants made a saccade with a latency <100 ms after stimulus onset to the target (considered a predictive saccade) or if they did not fixate the center of the screen before target onset. The number of discarded trials did not differ between groups (P > .5). One participant in the ASD‐group with a value > 2.75 sd above the overall mean in the social multisensory condition was considered an outlier and removed from further analysis. In sum, 15 children with ASD and 16 children with TD were included in the final analysis. After log transformation (all variables), assumption of normality was not violated according to the Kolmogorov‐Smirnov test (all Ps > .14). Descriptive statistics from the untransformed data is shown in Table 2. Fixations were identified using the Tobii Fixation Filter with velocity and distance threshold set to 35 pixels. Data was further analyzed in Matlab (Mathworks Inc., CA, USA) and SPSS (IBM corp., NY, USA).

Table 2.

Latency to First Fixation on the Eyes in Milliseconds (Untransformed Values). Means and (standard Deviations).

| Group | Unisensory (Silent) | Multisensory (Combined) | Multisensory (Social) | Multisensory (Nonsocial) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD | 764 (215) | 579 (143) | 616(223) | 598(170) |

| TD | 580 (207) | 718 (172) | 783(270) | 650(223) |

Results

Preliminary Analyses

In order to potentially simplify the main analysis (below), we first checked whether sound type played a differential role in the two groups, using an ANOVA with the two multisensory conditions (social, nonsocial) as within subjects factor and group entered as a between subjects factor. This analysis revealed no interaction effect (P = .31) or main effect of condition (P = .82), but a main effect of group F (1, 29) = 10, 218 P = .003, reflecting faster orienting to eyes in the ASD group. Given the lack of interaction effect in this analysis, we averaged the data from the two multisensory conditions in subsequent analyses, hereafter referred to as the multisensory condition.

Main Analyses

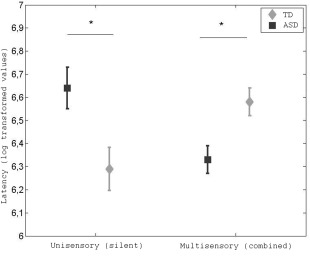

Latencies to orient to eyes in the multisensory and unisensory conditions are shown in Figure 2. An ANOVA with condition (silent, multisensory) as within subjects factor and group as between factors revealed a significant group x condition effect, F (1,29) = 24,028; P < .001. In a second step, we used t‐tests with Bonferroni‐corrected P‐values (corrected for four comparisons) to test the difference between specific means. Equal variances were not assumed. As predicted from the social orientation hypothesis of ASD, children with ASD oriented slower to the eyes than TD children in the unisensory condition, t (29) = 2.736; P = .044; d = 1.01. However, as already revealed by the results described in the preliminary analysis, a group difference in the opposite direction was found in the multisensory condition (note that the P‐value for this contrast holds for correction). Children with ASD oriented slower to the eyes in the unisensory condition compared to the multisensory condition, t (14) = 3.967; P = .005; d = 1.06. The TD group showed the opposite pattern, with slower orienting to the eyes in the multisensory condition compared to the unisensory condition, t (15) = 3.127; P = .027; d = 0.92. The results did not change when all four trials in the unisensory and social multisensory conditions were included in the analysis.

Figure 2.

Latency to first fixation on the eyes in milliseconds by group and condition (log transformed values) Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Statistical significance at P < .05 is denoted by * (Bonferroni corrected). See table 2 for untransformed values.

To analyze the effect of alerting cues on overall oculomotor speed, we calculated the mean latency to first fixation regardless of the location of the fixation as the dependent variable (i.e., also, including fixations landing at the nonsocial objects or between the AOIs). Again, condition (unisensory, multisensory) was added as within subjects factor and group as between subjects factor. This analysis revealed no main effect of group or condition, and no interaction effect (all P > .15).

Discussion

Consistent with the social orienting hypothesis, we found evidence of delayed orienting to eyes in young children with ASD compared to typically developing children. However, this group difference was only found on silent (unisensory) trials, whereas auditory alerting cues reversed the pattern of results. No difference was found between social and nonsocial sounds, suggesting that the effect was not dependent on a particular sound type. Although the exact mechanisms remain to be understood, our results indicate that social orienting cannot be understood without taking into account a possible influence of atypicalities in arousal and phasic alerting. Phasic alerting can have markedly different effects on behavior depending on tonic alertness. For example, people with reduced tonic alertness due to decreased noradrenergic activity show a particularly strong benefit of phasic alerting (Brown et al., 2015) This implies that differences in both baseline and phasic alerting could underlie the effect. Our results are therefore consistent with the notion that ASD is characterized by atypical arousal‐related processes (e g. Hirstein et al., 2001). Alerting cues can increase the detectability of stimuli of low salience (Kusnir et al., 2011). One possible explanation of the present results is that alerting cues increased the relative perceptual salience of eyes in the ASD group, and the salience of the distractors in the TD group.

It is notable that alerting cues did not differentially affect the groups' overall saccadic latencies. Rather, it is the latency to orient to eyes that is differentially affected. The results are therefore best interpreted as reflecting interactions between phasic alerting and brain mechanisms involved in orienting to eyes. This may suggest that during periods of high alertness, the autistic brain is biased toward selecting social stimuli for perceptual processing.

Our results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating atypical behavioral, brain and autonomic responses to eyes with direct gaze in people with ASD (Dalton et al., 2005; Kylliäinen & Hietanen, 2006), but stand in contrast to studies that found intact orienting to whole faces in adults with ASD (Shah et al., 2013). The latter discrepancy could be related to different levels of phasic alertness induced by the stimuli in the studies. However, the difference could also be related to the particular visual stimuli. Isolated eyes may activate eye‐selective neural processes more than whole faces (Itier & Batby, 2009). From this perspective, it might be informative to compare orienting to eyes and full face stimuli in ASD in future studies. It is also notable that eyes from fearful faces were used in the present study in order to maximize the likelihood of attentional orienting (Adolphs, 2010). Although it is not likely that fearful faces are represented by completely specialized mechanisms in this context, studies using a wider range of stimuli could be informative. Studies of social attention in ASD often use sounds to attract participants' attention to the screen (e g Elsabbagh et al., 2013). Our results suggest that sounds may affect children with ASD and TD differently, at least at the earliest stages of processing.

The present study is limited by its small sample size, but if the results are reproduced by independent studies, they have far reaching implications for our understanding of social orienting in ASD, and for reconciling some of the discrepant findings on social orienting in ASD.

Author Contributions

JLK conceived and designed the experiment under the supervision of TFY. JLK performed the data collection together with ET and analyzed the data under the supervision of TFY. JLK and TFY wrote the manuscript. ET contributed to the interpretation of the results and revised the manuscript critically. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sofia Lu for help with data collection, Christina Coco for expert advice on ADOS‐2 administration and scoring and Janina Neufeld for comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. This research was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (2015‐03670), Stiftelsen Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (NHS14‐1802:1) and the Strategic Research Area Neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet (StratNeuro).

References

- Adolphs, R. (2010). What does the amygdala contribute to social cognition? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1191, 42–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, D. O. , Wallace, G. L. , Sokoloff, J. L. , & Kenworthy, L. (2009). Brief report: IQ split predicts social symptoms and communication abilities in high‐functioning children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1613–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. B. , Tona, K.‐D. , van Noorden, M. S. , Giltay, E. J. , van der Wee, N. J. , & Nieuwenhuis, S. (2015). Noradrenergic and cholinergic effects on speed and sensitivity measures of phasic alerting. Behavioral Neuroscience, 129, 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, K. M. , Nacewicz, B. M. , Johnstone, T. , Schaefer, H. S. , Gernsbacher, M. A. , Goldsmith, H. , … Davidson, R. J. (2005). Gaze fixation and the neural circuitry of face processing in autism. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, G. , Toth, K. , Abbott, R. , Osterling, J. , Munson, J. , Estes, A. , & Liaw, J. (2004). Early social attention impairments in autism: Social orienting, joint attention, and attention to distress. Developmental Psychology, 40, 271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsabbagh, M. , Gliga, T. , Pickles, A. , Hudry, K. , Charman, T. , Johnson, M. H. , & the BASIS Team . (2013). The development of face orienting mechanisms in infants at‐risk for autism. Behavioural Brain Research, 251, 147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillon, Q. , Rogé, B. , Afzali, M. H. , Baduel, S. , Kruck, J. , & Hadjikhani, N . (2016). Intact perception but abnormal orientation towards face‐like objects in young children with ASD. Scientific reports, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirstein, W. , Iversen, P. , & Ramachandran, V. S. (2001). Autonomic responses of autistic children to people and objects. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 268, 1883–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itier, R. J. , & Batty, M. (2009). Neural bases of eye and gaze processing: the core of social cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 33, 843–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. H. , Senju, A. , & Tomalski, P. (2015). The two‐process theory of face processing: Modifications based on two decades of data from infants and adults. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 50, 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keehn, B. , Nair, A. , Lincoln, A. J. , Townsend, J. , & Müller, R.‐A. (2016). Under‐reactive but easily distracted: An fMRI investigation of attentional capture in autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keetels, M. , & Vroomen, J. (2011). Sound affects the speed of visual processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 37, 699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kylliäinen, A. , & Hietanen, J. (2006). Skin conductance responses to another person's gaze in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist, D. , Flykt, A. , & Öhman, A . (1998). The Karolinska directed emotional faces (KDEF). CD ROM from Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychology section, Karolinska Institutet, 91–630. [Google Scholar]

- Orekhova, E. V. , & Stroganova, T. A. (2014). Arousal and attention re‐orienting in autism spectrum disorders: Evidence from auditory event‐related potentials. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, S. E. , & Posner, M. I. (2012). The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 35, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, I. H. , & Caravan, H. (2004). Vigilant Attention In Gazzaniga M. (Ed.), The Cognitive Neurosciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, I. H. , Mattingley, J. B. , Rorden, C. , & Driver, J. (1998). Phasic alerting of neglect patients overcomes their spatial deficit in visual awareness. Nature, 395, 169–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, R. T. (2005). Developmental deficits in social perception in autism: the role of the amygdala and fusiform face area. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 23, 125–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, P. , Gaule, A. , Bird, G. , & Cook, R. (2013). Robust orienting to protofacial stimuli in autism. Current Biology, 23, R1087–R1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D . (2002). The Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Third Edition (WPPSI‐III). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D . (2003). Wechsler intelligence scale for childrenFourth Edition (WISC‐IV). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H. , Müller, H. J. , & Shi, Z. (2012). Non‐spatial sounds regulate eye movements and enhance visual search. Journal of Vision, 12, 2–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]