Abstract

Objectives

Undergraduate medical students are prone to struggle with learning in clinical environments. One of the reasons may be that they are expected to self‐regulate their learning, which often turns out to be difficult. Students’ self‐regulated learning is an interactive process between person and context, making a supportive context imperative. From a socio‐cultural perspective, learning takes place in social practice, and therefore teachers and other hospital staff present are vital for students’ self‐regulated learning in a given context. Therefore, in this study we were interested in how others in a clinical environment influence clinical students’ self‐regulated learning.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative study borrowing methods from grounded theory methodology, using semi‐structured interviews facilitated by the visual Pictor technique. Fourteen medical students were purposively sampled based on age, gender, experience and current clerkship to ensure maximum variety in the data. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and were, together with the Pictor charts, analysed iteratively, using constant comparison and open, axial and interpretive coding.

Results

Others could influence students’ self‐regulated learning through role clarification, goal setting, learning opportunities, self‐reflection and coping with emotions. We found large differences in students’ self‐regulated learning and their perceptions of the roles of peers, supervisors and other hospital staff. Novice students require others, mainly residents and peers, to actively help them to navigate and understand their new learning environment. Experienced students who feel settled in a clinical environment are less susceptible to the influence of others and are better able to use others to their advantage.

Conclusions

Undergraduate medical students’ self‐regulated learning requires context‐specific support. This is especially important for more novice students learning in a clinical environment. Their learning is influenced most heavily by peers and residents. Supporting novice students’ self‐regulated learning may be improved by better equipping residents and peers for this role.

Introduction

Students are prone to struggle with learning in clinical environments, especially when transitioning from preclinical to clinical medical education.1, 2, 3 Students may have a hard time understanding what they can expect and what is expected of them, resulting in high levels of uncertainty.4 In a clinical context that is not primarily designed for teaching and learning, students are no longer told what exactly to learn, and are expected to take control of their own learning.3 Being expected to engage in so‐called self‐regulated learning (SRL) poses a large challenge to undergraduate medical students.5

In SRL, an individual proactively modulates affective, cognitive and behavioural processes, to direct learning in order to achieve a desired level of competence.6 This includes goal setting, emotion control, environment structuring, gathering feedback and self‐reflection.6, 7 Many educators and researchers agree on SRL being beneficial for learning.8, 9 Following Brydges and Butler's situated model of SRL, SRL results from a complex process that happens in the interaction between an individual and the context in which learning takes place.9 Consequently, both individual and context influence the process and outcome of SRL.10 Therefore, SRL is known to be difficult in a hectic, ever‐changing environment, such as the hospital.11

A broad variety of contextual factors, including historical, cultural, pedagogical, physical and social factors, have been described to influence students’ SRL.6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 From a socio‐cultural perspective, workplace‐based learning is a social process and consequently social factors are essential.16 Social factors that have been described to influence students’ SRL include other people in a workplace, students’ relationships with them, students’ familiarity with them, the feedback they give to students, the willingness of other people to create opportunities for students to engage in SRL and practice independently, these peoples’ experience in and motivation for teaching, the engagement of students in the team and the social support students receive from the team.9, 11, 13 Previous research has focused on specific aspects of social factors that influence student learning in a clinic, such as how students use peers to compare their performance and develop an identity in a clinical environment.17, 18, 19 However, to our knowledge there have not been any studies on how others influence the process of self‐regulated learning in clinical settings, including goal setting, various regulatory mechanisms and regulatory appraisals.6

In this study we were specifically interested in: who are the people in a clinical environment affecting students’ SRL, how these people have an influence and to what extent. This knowledge is of importance because gaining a deep understanding of how other people in a clinical environment can support or hinder students’ SRL can aid future attempts to improve contextual support for clinical students’ SRL. Therefore this study aims to answer the following research question: How do medical students perceive the influence of other people in clinical settings on their self‐regulated learning?

Because of our socio‐cultural perspective on SRL in clinical settings, it is important to study students’ SRL experiences holistically.16 Various tools for assessing self‐regulation have been developed, ranging from measurement tools to microanalysis protocols.20 However, we explicitly wanted to focus on the influence of other people. Because it can be difficult for participants to bring to mind all people involved in a complex setting, we chose to use a qualitative methodology consisting of semi‐structured interviews supported by a visual technique (the Pictor technique) to answer our research question.21, 22, 23

Method

Design

We position ourselves in a constructivist paradigm, believing that reality is subjective and context‐specific and that there is no ultimate truth.24 We carried out a qualitative study borrowing methods from grounded theory methodology in order to do a systematic analysis of participants’ perspectives on relationships that are influential in their engagement in SRL, using purposive sampling and iteratively gathering and analysing data until theoretical sufficiency was reached.25 We chose an individual approach for the data collection to create a safe environment in which students would feel free to elaborate on their personal experiences.

The research group consisted of researchers with varied experiences and backgrounds to enhance interpretation and understanding of our findings using multiple perspectives. The first author (JB) is a recently graduated MD and a PhD candidate in health professions education. All other authors have PhDs in health professions education and have different backgrounds, including elderly care medicine (EH), obstetrics and gynaecology (PT), psychology and psychometrics (CvdV) and veterinary medicine (AJ).

Setting

We recruited medical students from one large Dutch medical school with entering cohorts of 350 students per year. The medical curriculum includes a preclinical phase (years 1–3) and a clinical phase (years 4–6). The clinical phase consists of rotational clerkships ranging from 3 to 16 weeks. During these clerkships, medical students participate in a wide range of activities regarding patient care. All students are supported similarly and are closely supervised. Students are usually supervised by residents when learning in wards, delivery rooms and emergency rooms, and consultants in out‐patient clinics, operating theatres, public‐health institutions, nursing homes and general practices. Both residents and consultants provide formative feedback using mini‐CEX‐like forms, but only consultants provide a final summative assessment at the end of a clerkship. Generally, three to 10 students are enrolled in a clerkship simultaneously but they infrequently collaborate, except when learning on the wards and during formal educational meetings.

Participants

To ensure a wide variety in experiences, the participants were purposively sampled regarding age, gender, experience and current clerkship. We included students who were enrolled in different clerkships, and included students who were in different years of the clerkships because students are expected to learn and act increasingly independently as they progress through the curriculum. Between July and October 2015, the first author (JB) approached students during educational meetings and sent invitations to participate by e‐mail. We included 14 students. Details of the participants are given in Table 1. After the interview, participants were given a €10 gift certificate as compensation for their time.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Fictional name | Gender | Age (years) | Current clerkship | Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victoria | Female | 22 | Surgery | 4th year |

| David | Male | 25 | Surgery | 4th year |

| Josh | Male | 23 | Neurology | 5th year |

| Marlon | Male | 24 | Neurology | 5th year |

| Demi | Female | 27 | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 5th year |

| Jamie | Male | 26 | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 5th year |

| Hayley | Female | 25 | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 5th year |

| Megan | Female | 24 | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 5th year |

| Tom | Male | 29 | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 5th year |

| Maggie | Female | 25 | Paediatrics | 6th year |

| Anita | Female | 27 | Internal medicine | 5th year |

| Laci | Female | 25 | Geriatrics | 6th year |

| Amy | Female | 26 | Plastic, reconstructive and aesthetic surgery | 6th year |

| Jennifer | Female | 27 | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 6th year |

Data collection

The first author conducted all the interviews. Because he has recently experienced the clerkships himself, he was able to relate to the students’ narratives and envision their experiences. This allowed for meaningful follow‐up questions to enhance insight into the experience and questions regarding emotional reactions to the experience described. The first author's experience in SRL research allowed for specific questions regarding constructs related to various SRL theories as described by Sitzmann and Ely.6 A possible adverse effect might have been that follow‐up questions were too focused or coloured by personal experiences. By continuously reminding himself of this, by frequently reading interview transcripts with other team members, and by iteratively gathering and analysing data, he attempted to appropriately balance this.

After obtaining informed consent and some background information regarding demographics and medical interests, the interviewer briefly explained that self‐regulated learning refers to directing ones’ own learning through goal setting, planning, monitoring, reflecting on progress and thinking about future learning. Next, he asked participants to construct a representation of roles and relationships of other people in a specific setting following the Pictor technique as originally described by King et al.23 Students were instructed to write all people or groups influencing their self‐regulated learning on arrow shaped adhesive notes and to stick these notes to a large sheet of paper, creating a visual representation or story of how their SRL was influenced by the people depicted on the arrows. Participants were not limited in any way in portraying their experiences. They were invited to include explanatory words, arrows or other visual tools and were allowed to change their Pictor chart throughout the interview. We used the visual representation as a prompt to help participants tell their stories not only through words but also visually. The interviews following the creation of the Pictor charts lasted for approximately 1 hour.

The interviews were audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim. We gave all students an alias. The first author performed a preliminary analysis after each interview and provided participants with a half‐page summary of the interview to enable a member check. Participants also received a picture of their charts and were asked if any supplemental changes were desired. Nine participants verified the summary of the interview, one of them recommended small changes and one supplied additional information that was not addressed during the interview. All of these 11 participants agreed with the Pictor chart. Three participants did not respond to the request.

Data analysis

After each interview, the first author (JB) open coded both the transcripts and the Pictor charts using constant comparison to review and match the data in the transcript and Pictor chart. The interview transcripts and Pictor charts were constantly inductively compared using open coding. Emerging concepts were used to guide the following interviews with other participants. Open coding was followed by axial coding and interpretive analysis.

The first and second author (JB and EH) discussed the transcripts, Pictor charts and emerging concepts of the analysis biweekly during a period of 4 months. Additionally, we discussed the emerging ideas and interesting findings with the research group during the analysis and writing‐up, six times in total. To keep track of our interpretations, the first author kept memos and a log to record all emerging ideas and concepts. We used the situated sociocultural theory of SRL by Brydges and Butler and the constructs involved in SRL as reported in Sitzmann and Ely's meta‐analysis, as sensitising concepts supplementary to our analysis.6, 9, 26 Data analysis was supported by the use of MaxQDA V11 (Verbi GmbH, Berlin, Germany).

Ethical considerations

The Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO) approved the study under file number 535.

Results

Students described the roles of other people in the workplace and their influence on their learning in many different ways. Arrows were arranged to represent negative or positive influences, their importance, power differences, barriers that were felt in relationships, amount of effort invested in relationships, flow of knowledge or developments over time. Students used between six and 15 arrows to depict these issues in their Pictor charts.

People could influence students’ SRL through affecting role clarification, goal setting, learning opportunities, self‐reflection and emotional coping. Many of the more experienced students expressed that they perceived large changes in their perceptions of the roles of, and relationships with, others in the workplace as they progressed through the clerkships. We will illustrate our findings by focusing on two extreme situations: novice students at the start of clerkships and experienced students. However, it must be noted that variation existed between all participants. Not all of the more senior students reported earning like an experienced student in a clinical context and some junior students explained their learning like an experienced student from the onset of clinical training. In the last section of the results, we will include a description of how experienced students explained their transition from learning as a novice to learning like a (more) experienced student. Table 2 summarises our findings.

Table 2.

Summary of how others in a clinical environment influence novice and experienced undergraduate students’ self‐regulated learning in clerkships

| Others important for students’ SRL through | Novice student | Experienced student |

|---|---|---|

| Role clarification | Very dependent on peers | Know who they want to become, little need for support |

| Goal setting | Reactive learning goals depend on questions from all others around and patients’ illnesses. Personal goals often derived from peers. External goals set by residents, consultants and the curriculum | Reactive learning goals depend on questions of nursing staff and patients’ illnesses. Personal goals are communicated to supervisors. External goals set by residents |

| Learning opportunities | Very dependent on residents. Peers, consultants and nursing staff are also important | Dependent on residents and consultants. Peers also important |

| Self‐reflection | Dependent on nursing staff, peers, patients, residents and consultants | Dependent on nursing staff, peers, residents and consultants |

| Coping with emotions | Dependent on peers, family and friends | Dependent on residents, peers, family and friends |

Novice students in clerkships

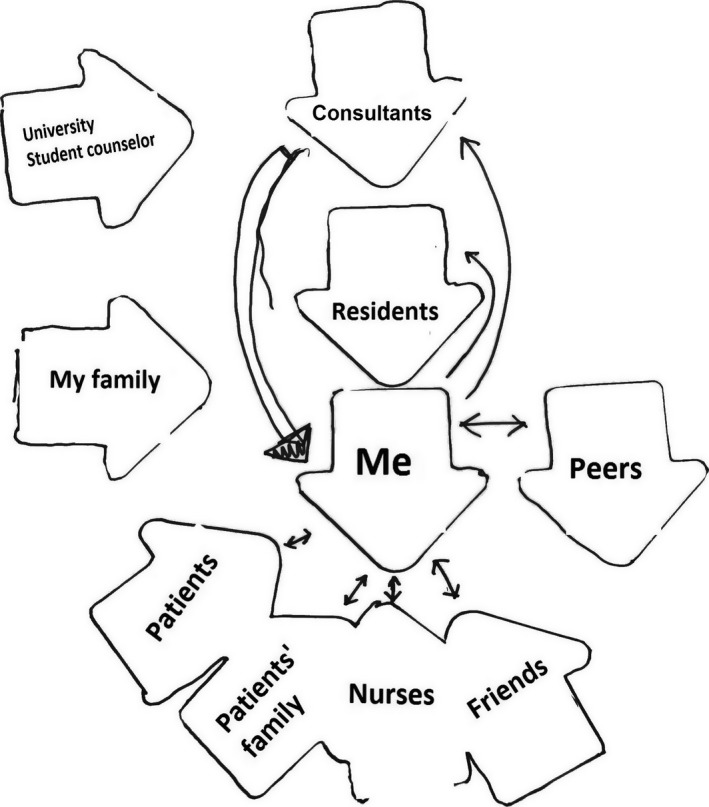

A novice student metaphorically can be characterised by a pinball being shot into a pinball machine. Students were launched into clerkships and they bounced back and forth in a clinical setting without a clear trajectory, which is illustrated by the Pictor chart of Marlon (Fig. 1). He portrayed how he perceived that knowledge usually flows from consultants through residents to him. During this process, many people interacted with him and influenced his SRL, visualised by the bidirectional arrows. His Pictor chart illustrates how many novice students describe having close relationships with residents and with peers. The influence of others, such as patients, nurses and consultants, in a clinical environment on novice students’ SRL was much smaller. We will therefore first focus on how residents and peers influenced novice students’ SRL and afterwards on the influence consultants, nurses and patients could have.

Figure 1.

Marlon's Pictor chart representing how others influence his SRL

Residents played a decisive role in novice students’ SRL because they are the people students spend most of their time with. Residents could facilitate aspects of SRL. Residents influenced novice students’ goal setting through helping students decide what goals they should be working on, stimulated reactive on‐the‐spot learning through the questions they asked, and played an important role in aiding self‐reflection because they gave feedback to students and stimulated reflection by simple questions such as: What did you learn today? Novice students explained how they used residents’ behaviours and competencies as a standard of reference for self‐assessment of their own competencies, indicating how a major goal of many novice students was to be able to function as a resident.

Peers were the other group of people who played an important role in many novice students’ SRL. Similar to residents, peers could also facilitate all aspects of SRL. When novice students faced uncertainty in their new roles and were unclear of what was expected of them, they often asked more experienced peers to show them around. Besides a basic introduction, this gave them some idea of what realistic learning goals may be and the specific dos and don'ts of the department. Students experienced a low barrier to asking peers for help, and peers could also trigger reactive on‐the‐spot learning by asking each other questions. Some high‐functioning peers could even serve as role models. Lastly, peers played a similar role to residents in the self‐reflection process of SRL by setting a standard of reference for self‐assessment through social comparison and by stimulating reflection through questions. Additionally to this, peers played a unique role in novice students’ SRL because they could assist in coping with emotional reactions resulting from experiences in a clinical environment. Sharing emotional experiences with their peers was experienced as an important source of social support. However, some students also reported peers hindering their SRL because they experienced a feeling of competition.

My first real clerkship was pediatrics, here [at the academic hospital] a peer showed me around a little,… but not really […] Even though they are instructed to do so of course, they see you as competition. They think: if I make a better impression, I'll get a higher grade […] They really throw you into the deep end, and may enjoy not explaining things to you, because they then have the advantage over you of knowing how to do it.

(Jennifer)

In their Pictor charts novice students also referred to consultants, nurses and patients as influencing their SRL, but to a lesser extent. Consultants could instruct novice students about the goals they could be working on, although novice students explained that they rarely had contact with consultants. Besides goal setting, consultants and nurses played an important role in creating a safe learning environment and a positive atmosphere and engaging students in the team. This facilitated novice students’ SRL strategies because this permitted them to make mistakes, ask questions, create learning opportunities and seek feedback. Novice students also learned by observing others such as consultants and nurses. This role model function is exemplified in the quote by Megan. A patient's influence was limited to affecting learning opportunities because a patient's problem determined the content of learning opportunities. Questions from patients and their families, similar to questions from consultants and nurses, could also initiate reactive on‐the‐spot learning.

They won't teach me how a disease works [….] but I think they can show you how to treat patients […] You also look at the …. at other students, well at everyone, also residents and consultants. Everyone treats patients differently, so you can decide for yourself what you believe is good and bad […] Sometimes it is good to see something not go very well, to make you realise: this did not go well, and sometimes you think: yes, I would like to be able to do this.

(Megan [about nurses])

Experienced students in clerkships

If novice students can be characterised as pinballs in a pinball machine, experienced students can be thought of as snowballs rolling downhill. These students explained a clear trajectory in their learning, becoming more powerful whilst rolling, and that only significant obstacles could deviate them from their path. The Pictor chart of Laci (Fig. 2) illustrates this visually. The proximity of the arrows to herself portrays how she perceived many others, such as physician assistants and nurses, to be beneficial to her SRL. Laci's Pictor chart is also more structured than Marlon's and symbolises how she understood the clinical environment and felt like a true member of the clinical team. She discussed having strategies to use all people in her Pictor chart to benefit her learning. Because of these strategies, the influence a single person had on her SRL in general was smaller than for novice students. Experienced students often had a clear objective of what kind of doctor they wanted to become. They did not need peers to help with goal setting, but were more dependent on the help of consultants to assist them in creating adequate learning opportunities. This is illustrated in Laci's Pictor chart, compared with Marlon's chart, as the distance between the arrow representing peers and her own is larger, whereas the arrows representing consultants are closer to her own and consultants of other specialties are also mentioned. We will discuss the roles of residents, peers, consultants, nurses, patients and others in the same order as for the novice students.

Figure 2.

Laci's Pictor chart representing how others influence her SRL

The role of residents is different for experienced students compared with novice students, because experienced students started to regard residents as near‐peers. This resulted in residents affecting all aspects of SRL, but not being decisive in the SRL of experienced students. Additionally, residents may also support coping with emotional experiences and may create a feeling of social support. Experienced students were also more likely to share their personal goals with residents. This was because they realised the residents might be able to provide effective strategies to reach certain goals, as residents were likely to have recently been in a similar situation. In the interviews, students emphasised that it was important that residents provided experienced students with the autonomy and responsibilities they require in order to support their SRL, instead of just directing what students had to do or learn.

What often happens is that they [residents] manage all patients and tell you: please call this‐and‐that person, and you know you won't learn much from doing so, you should think of calling those people yourself […] in the beginning it might be useful learning how to arrange things, but at a certain point you should be expected to think of that.

(Josh)

Similar to novice students, experienced students also frequently used peers for their SRL. Peers could influence all aspects of SRL, but their influence was smaller. Student‐peers did not have a large influence on their goal setting and experienced students were able to cope with the emotional experiences of a clinical environment; therefore, the need for emotional support was smaller. Peers do have an influential role in experienced students’ SRL, for instance by functioning as a frame of reference, as Jennifer explained.

In your final clerkship there are peers around you who do the same clerkship, at the same time, in another hospital. You can compare them to yourself. “What things did you do?”, “What are you allowed to do independently and what not?”, and then you compare yourself to that: “Which of those things would I like to do?”. So I think peers doing the same clerkships, at the same time, in another hospital, still have had an influence on my learning.

(Jennifer [talking about peers])

The role of consultants in the learning of experienced students was much bigger than for novice students because they partially fulfill the role residents’ play in novice students’ SRL. Consultants had little influence on goal setting, but had a large impact on learning opportunities and strategies because consultants were regarded as experts who could grant students the most interesting and challenging learning opportunities. Together, consultants and residents had a major influence on experienced students’ opportunities for SRL. Most experienced students described a smaller dependence on the safety of the learning environment created by consultants, residents and peers. Because they knew what they wanted, they would ask for focused feedback when they felt they needed it, and explained that they cared more for learning than assessment. Experienced students explained that consultants, residents, peers and nurses with low motivation could hinder the amount of effort they put in, but that students themselves still had their own intrinsic motivation, goals and learning strategies to rely on. Especially important for many experienced students’ SRL was a feeling of autonomy, getting increasing responsibilities in line with their goals, and being surrounded by stimulating people.

In my final clerkship it was the first time I told patients the diagnosis and treatment plan. Of course that's pretty strange. It is a real part of … but until the final clerkship you don't do that yourself, discussing the diagnosis and treatment plan. You may take a history and physical examination, but then you return [to the consultant], explain your findings and discuss: “well what do you think it is and how should we proceed?” “Well” says the consultant, “I would do the same thing”, but then he ends up delivering the message […] but really I think: “well, if you agree, let the student deliver the message”.

(Maggie)

The influence of others, such as nurses and the people in charge of the planning, on experienced students’ SRL in a clinical environment is large in comparison to novice students. Experienced students felt more a part of a clinical team and knew how to involve others in their SRL strategies. Experienced students would share their goals with many others, including peers, consultants and nurses, using their knowledge to discuss which strategy to use to achieve their goals.

During my last clerkship, I discussed with one of the nurses whether an elective on the neonatal intensive care unit would be a smart move. Yes you talk about that […] I find teamwork very important so maybe that is resembled in this.

(Amy)

Transitioning from novice into an experienced student

Looking back on their clerkships, many of the experienced students explained how they had changed because they gradually realised they needed to take control of their learning. Taking control of one's learning led to more focused learning goals, using more efficient learning strategies, and asking for feedback on achieving the competencies students felt they needed. There were multiple ways students described this process. Many experienced students explained that this happened after 3–6 months in the clerkships.

At that point they started to realise what type of doctor they wanted to become and set learning goals accordingly. They felt more comfortable in a clinical environment and realised they could be of added value to a clinical team, instead of being a ‘nuisance’. Many students described having effective strategies to cope with emotional clinical situations. They frequently involved many people in their learning by asking questions, and asking for learning opportunities and feedback. They experienced less of a hierarchical barrier when talking to consultants and residents were no longer idolised, but often seen as more experienced near‐peers. In the following quote, Josh explained how he realised his learning changed after receiving feedback from a resident.

Residents say to you: yes, just imagine there is no supervisor […] always assume there is no backup. Always think of a conclusion and treatment plan, because if you don't … I thought that was very good advice actually. Of course you are not always right, but if you try this it will make the transition to residency easier […] and you learn more I think. You just have to …. think of things yourself and then you realize what problems you might face.

(Josh)

Discussion

Our study provides insight into how other people influence undergraduate medical students’ SRL in a clinical environment through affecting role clarification, goal setting, learning opportunities, self‐reflection and emotional coping. Our findings provide insight into how others can have a large influence on students’ SRL through the formal curriculum, the informal curriculum, and perhaps even part of the hidden curriculum. The descriptions by students of the roles of these other people were indicative of different phases in how students engage in SRL as a novice and as an experienced student. As novices, students’ social contexts are limited to the medical team they work with. As a result, novice students’ SRL often heavily relies on the support of residents and peers. It can be easily affected by anyone interacting with them, and therefore their SRL may often have the unpredictable trajectory of a pinball. By contrast with novice students, experienced students appear to be able to enhance their understanding of a clinical environment, enabling them to better navigate the social context and find support in reaching specific goals. Their SRL is further supported as these students get a grasp of learning in a clinical environment, knowing what their role is, and knowing who they want to become. This results in their SRL following a clearer trajectory of a snowball rolling downhill.

How students perceive others to influence their SRL seems to result from interpreting culture, pedagogy and a social environment differently. Novice students are often unable to navigate a clinical workplace culture because of a lack of understanding of their role in it. Novice students expect others to actively engage in their learning. Novice students themselves only actively involve people they have frequent interactions with in their SRL. Experienced students on the other hand tried to build relations with many people they worked with. They more actively tried to engage consultants in their learning and benefit from it.

Novice students reported their SRL to be hindered by a feeling of being of little added value or even being a nuisance to a clinical team. This feeling may be founded in their preclinical education and reflect how they are historically trained to learn, as a person's SRL is influenced by history and experiences.9 Novice students had difficulty coping with this emotional stress because it made them feel unwanted. They explained that this could decrease their motivation for SRL and required emotional support from peers to overcome these feelings. Emotional support by peers could be inhibited if there was a feeling of competition among students.

The transition from novice to experienced student appeared to rely on an adequate understanding of a clinical environment. This closely relates to theories regarding communities of practice.27, 28 This perspective strengthens the case for longer clinical placements, because longer exposure facilitates students’ understanding of a clinical community of practice, and consequently what a student's role in a team might be.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our study lies in the use of the Pictor technique. This technique allowed us to study the subject holistically using a constructivist paradigm. It also functioned well as a prompt for the semi‐structured interview and made intangible barriers visible. Nonetheless, interviews and in fact all recall studies suffer to some degree from memory bias (e.g. increasing the role of one's own conscious will).29 Additionally, participants may have reported how others influenced their SRL more consciously than they would have if they were unaware of the topic of this study.

Because the interviewer explained to the students before the interview that he only has had a short postgraduate, non‐medical, career, there was little to no hierarchical barrier present, allowing for more disclosure. However, students’ experiences that were similar to the experiences of the interviewer may have provoked more follow‐up questions than experiences that did not feel familiar to the interviewer.

We believe our results are likely to be largely transferable within our Dutch educational context. However, as previously described, social relationships are highly dependent on culture30 and national culture may influence medical curricula.31 It is therefore likely that our findings regarding the roles of others and their importance for students’ SRL would be different in other cultures.

Implications for practice and future research

The ways in which faculty members and others in a clinical context can support undergraduate clinical students’ SRL are still largely under‐researched. However, our results do provide an insight into how social influences affect students’ SRL. Our findings hint at possible ways to support undergraduate students’ SRL in a clinical environment.

First of all, our findings strengthen the belief that expecting novice students to fully self‐regulate their learning in a new environment may be very difficult for many. Thus, novices may benefit from active support by others. Our results also show that novice students report rarely interacting with consultants. In this context, development initiatives may therefore be better focused on residents to enable them to effectively support students’ SRL. The importance of residents and peers for students’ learning in a clinical environment has been described before regarding role modelling and social comparison.18, 32 Our results emphasise this importance even more (especially for novice students) because students reported that peers and residents have the largest impact on their goal setting, opportunities, SRL strategies and self‐reflection. Perhaps most importantly, a student's transition from a novice ‘pinball’ to an experienced ‘snowball’ and subsequent SRL in a clinical environment appears to result from feeling comfortable in a clinical environment and facilitates working towards personal goals. Therefore supporting students’ SRL in a clinical environment could be improved by lengthening student placements in a clerkship, following principles of longitudinal integrated clerkships and early clinical encounters. This enables students to find their way in the culture of the community, including the vocabulary, reduces the stress of transitions, helps novice students understand their role and ultimately helps students become part of the health care team.28, 33, 34, 35

We suggest that future research should focus on gaining a better understanding of how students transition into clerkships and how they navigate the clinical communities of practice of a clinical environment, for instance using ethnographic methodologies. This could help us understand how students start to learn like an experienced student. A longitudinal study design could increase our understanding of this transition and may shed some light on how best to support the individual student through the transition from novice to experienced student and how this can be supported by peers and residents, because they have most contact with novice students in a clinical environment. Lastly, our findings about social influences on students’ SRL give an insight into how SRL is not only influenced by the formal curriculum, but also the informal and hidden curricula. This topic has been addressed sparsely in previous research and requires a more thorough understanding.36

Conclusion

The influence others in a clinical environment have on undergraduate students’ SRL is different for novice and experienced students. The role of residents and peers is highly decisive for many novice students and the roles of others are more marginal. The role of residents and peers in experienced students’ SRL is also large, but other people such as consultants also play important roles. Students reported that transitioning from novice to experienced learning behaviours was the result of feeling more confident in their role in a clinical environment. Supporting the transition from novice to experienced student by helping students understand a clinical environment and their role in it, is therefore likely to be beneficial for students’ engagement in SRL in a clinical environment.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, and to the acquisition of data. JB took responsibility for data analysis and served as principal author. EH and PT made important contributions to data analysis and interpretation, and to the writing of the manuscript. AJ and CvdV contributed to data analysis and to the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding

none.

Competing interests

none.

Ethical approval

The Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO) approved the study under file number 535.

Acknowledgements

none.

References

- 1. Prince KJAH, Boshuizen HPA, Van der Vleuten CPM, Scherpbier AJJA. Students’ opinions about their preparation for clinical practice. Med Educ 2005;39 (7):704–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Greenberg L, Blatt B. Perspective: successfully negotiating the clerkship years of medical school: a guide for medical students, implications for residents and faculty. Acad Med 2010;85 (4):706–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Teunissen PW, Westerman M. Opportunity or threat: the ambiguity of the consequences of transitions in medical education. Med Educ 2011;45 (1):51–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prince KJAH, Van de Wiel MWJ, Scherpbier AJJA, Van der Vleuten CPM, Boshuizen HPA. A qualitative analysis of the transition from theory to practice in undergraduate training in a pbl‐medical school. Adv Heal Sci Educ 2000;5 (2):105–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. White CB. Smoothing out transitions: how pedagogy influences medical students’ achievement of self‐regulated learning goals. Adv Health Sci Educ 2007;12 (3):279–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sitzmann T, Ely K. A meta‐analysis of self‐regulated learning in work‐related training and educational attainment: what we know and where we need to go. Psychol Bull 2011;137 (3):421–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bjork RA, Dunlosky J, Kornell N. Self‐regulated learning: beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annu Rev Psychol 2013;64:417–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sandars J, Cleary TJ. Self‐regulation theory: applications to medical education: AMEE Guide No. 58. Med Teach 2011;33 (11):875–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brydges R, Butler D. A reflective analysis of medical education research on self‐regulation in learning and practice. Med Educ 2012;46 (1):71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Butler DL, Cartier SC. Multiple Complementary Methods for Understanding Self‐Regulated Learning as Situated in Context. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berkhout JJ, Helmich E, Teunissen PW, van den Berg JW, van der Vleuten CPM, Jaarsma ADC. Exploring the factors influencing clinical students’ self‐regulated learning. Med Educ 2015;49 (6):589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Butler DL, Cartier SC, Schnellert L, Gagnon F, Giammarino M. Secondary students’ self‐regulated engagement in reading: researching self‐regulation as situated in context. Psychol Test Assess Model 2011;53 (1):73–105. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zumbrunn S, Tadlock J, Roberts ED.Encouraging self‐regulated learning in the classroom: a review of the literature. Richmond, VA: Metropolitan Educational Research Consortium (MERC) 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Azevedo R. Theoretical, conceptual, methodological, and instructional issues in research on metacognition and self‐regulated learning: a discussion. Metacognition Learn 2009;4 (1):87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boor K, Scheele F, van der Vleuten CPM, Teunissen PW, den Breejen EME, Scherpbier AJJA. How undergraduate clinical learning climates differ: a multi‐method case study. Med Educ 2008;42 (10):1029–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bleakley A. Broadening conceptions of learning in medical education: the message from teamworking. Med Educ 2006;40 (2):150–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raat AN(J), Kuks JBM, van Hell EA, Cohen‐Schotanus J. Peer influence on students’ estimates of performance: social comparison in clinical rotations. Med Educ 2013;47 (2):190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Raat JAN, Kuks JBM, Cohen‐Schotanus J. Learning in clinical practice: stimulating and discouraging response to social comparison. Med Teach 2010;32 (11):899–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haidet P, Hatem DS, Fecile ML, Stein HF, Haley HL, Kimmel B, Mossbarger DL, Inui TS. The role of relationships in the professional formation of physicians: Case report and illustration of an elicitation technique. Patient Educ Couns 2008;72 (3):382–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cleary TJ, Callan GL, Zimmerman BJ. Assessing self‐regulation as a cyclical, context‐specific phenomenon: overview and analysis of SRL microanalytic protocols. Educ Res Int 2012;2012:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ross A, King N, Firth J. Interprofessional relationships and collaborative working : encouraging reflective practice. Online J Issues Nurs 2005;10 (1). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fenwick T, Nerland M, Jensen K. Sociomaterial approaches to conceptualising professional learning and practice. J Educ Work 2012;25 (1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 23. King N, Bravington A, Brooks J, Hardy B, Melvin J, Wilde D. The Pictor technique: a method for exploring the experience of collaborative working. Qual Health Res 2013;23 (8):1138–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bunniss S, Kelly DR. Research paradigms in medical education research. Med Educ 2010;44 (4):358–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bowen GA. Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. Int J Qual Methods 2006;5 (3):12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge university press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge university press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wegner DM. The mind's best trick: how we experience conscious will. Trends Cogn Sci 2003;7 (2):65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wong AK. Culture in medical education: comparing a Thai and a Canadian residency programme. Med Educ 2011;45 (12):1209–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jippes M, Majoor GD. Influence of national culture on the adoption of integrated medical curricula. Adv Health Sci Educ 2011;16 (1):5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Karani R, Fromme HB, Cayea D, Muller D, Schwartz A, Harris IB. How medical students learn from residents in the workplace. Acad Med 2014;89 (3):490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ogur B, Hirsh D, Krupat E, Bor D. The harvard medical school‐Cambridge integrated clerkship: an innovative model of clinical education. Acad Med 2007;82 (4):397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hauer KE, Hirsh D, Ma I, Hansen L, Ogur B, Poncelet AN, Alexander EK, O'Brien BC. The role of role: learning in longitudinal integrated and traditional block clerkships. Med Educ 2012;46 (7):698–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Diemers AD, Dolmans DHJM, Verwijnen MGM, Heineman E, Scherpbier AJJA. Students’ opinions about the effects of preclinical patient contacts on their learning. Adv Health Sci Educ 2008;13 (5):633–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Woods NN, Mylopoulos M, Brydges R. Informal self‐regulated learning on a surgical rotation: uncovering student experiences in context. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2011;16 (5):643–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]