Abstract

Background

The conduct of oral food challenges as the preferred diagnostic standard for food allergy (FA) was harmonized over the last years. However, documentation and interpretation of challenge results, particularly in research settings, are not sufficiently standardized to allow valid comparisons between studies. Our aim was to develop a diagnostic toolbox to capture and report clinical observations in double‐blind placebo‐controlled food challenges (DBPCFC).

Methods

A group of experienced allergists, paediatricians, dieticians, epidemiologists and data managers developed generic case report forms and standard operating procedures for DBPCFCs and piloted them in three clinical centres. The follow‐up of the EuroPrevall/iFAAM birth cohort and other iFAAM work packages applied these methods.

Recommendations

A set of newly developed questionnaire or interview items capture the history of FA. Together with sensitization status, this forms the basis for the decision to perform a DBPCFC, following a standardized decision algorithm. A generic form including details about severity and timing captures signs and symptoms observed during or after the procedures. In contrast to the commonly used dichotomous outcome FA vs no FA, the allergy status is interpreted in multiple categories to reflect the complexity of clinical decision‐making.

Conclusion

The proposed toolbox sets a standard for improved documentation and harmonized interpretation of DBPCFCs. By a detailed documentation and common terminology for communicating outcomes, these tools hope to reduce the influence of subjective judgment of supervising physicians. All forms are publicly available for further evolution and free use in clinical and research settings.

Keywords: decision‐making, double‐blind method, food hypersensitivity, oral food challenge, symptom assessment

Abbreviations

- CRF

case report form

- DBPCFC

double‐blind, placebo‐controlled food challenge

- FA

food allergy

- iFAAM

integrated approaches to food allergen and allergy risk management

- IgE

immunoglobulin E

- SOP

standard operating procedure

- SPT

skin prick test

In the clinical setting, diagnosing food allergy (FA) requires a comprehensive workup, including a detailed history, individualized decisions for assessing sensitization and, if warranted, oral food challenges guided by recently developed standards 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. However, there is no established methodology for systematically assessing FA in research settings, which would require a priori defined approaches suitable for entire study populations. The multinational EuroPrevall birth cohort study pioneered a systematic framework to estimate the frequency and patterns of FA in European children 7, 8. It has been recognized that thorough oral food challenges are required to confirm suspected allergic reactions to food in observational and intervention studies, preferably as double‐blind placebo‐controlled food challenges (DBPCFC). Supervised open food challenges (no placebo test, no blinding) are considered sufficient to prove tolerance to a specific food item 9. A group of clinical FA researchers suggested guidelines for a standardized assessment of DBPCFCs in such research settings (PRACTALL) 1. Although oral food challenge tests in clinical settings have been increasingly harmonized, their results are not always clear‐cut and their interpretation is still challenging, particularly for comparative systematic evaluations 10, 11, 12, 13.

Our aim was to develop a diagnostic toolbox to identify individuals with possible FA who should undergo a DBPCFC for use in population‐based and clinical studies and to make recommendations for a stringent documentation and interpretation of food challenge results.

Methods

The interobserver differences experienced in the EuroPrevall birth cohort's highly standardized food challenges prompted our development of a new toolbox of refined methods for diagnosing FA. The follow‐up assessment of the EuroPrevall birth cohort as part of the pan‐European iFAAM project (EU grant agreement number 312147) already applied these methods. They were developed as generic blueprints, applicable in observational and interventional research, and routine care. The case report forms (CRFs) and standard operating procedures (SOPs) are publicly and freely available. Paediatricians, dieticians, epidemiologists and data managers with extensive experience in translational research and clinical practice led the development of these tools, based on the previously published guideline of the PRACTALL group 1. Three specialist clinics (Southampton and Manchester, UK; Berlin, Germany) piloted all CRFs and SOPs.

Recommendations

Questionnaire assessment of earlier FA history

We propose a number of new questions for the assessment of prior reactions to foods. These questions are phrased for parent‐ or self‐reported reactions. To allow the calculation of comparable frequency estimates in research settings, a list of commonly observed allergenic foods should be presented. Further (country‐ and culture‐specific) suspected food allergens can be added and should be reported as free text. Three different diagnostic levels are distinguished as follows: parent‐/self‐reported reactions to food (‘Have you/Has your child ever had an illness or trouble caused by eating a food or foods and/or a diagnosis of food allergy?’ Yes/No), parent‐/self‐reported doctor's diagnosis of FA (‘Have you/Has your child ever been diagnosed by a doctor as having an allergy to this food?’ Yes/No) and parent‐/self‐reported challenge‐proven FA (‘if yes, was this diagnosis supported by a food challenge in a clinic or practice?’ Yes/No or don't know).

Age (in years, optional: in months, for the first one/two years) at first symptoms/diagnosis (‘How old were you/was your child when these symptoms first occurred?’) and when the patient was eating the food again without symptoms (‘I/The child was able to eat the food without symptoms beginning at the age of:’) or when the patient last ate the food with subsequent symptoms (‘I/The child had symptoms the last time I/he/she ate the food at the age of:’) can be used as indicators of onset, disease duration and tolerance development. Furthermore, parent‐/self‐reported symptoms (e.g. itching, rash, diarrhoea) and the interval between exposure and symptoms should be recorded (‘How soon after eating did the symptoms occur?’ Within 2 h/After 2 h/Both).

Medical history and sensitization status

Current FA status of a patient can be evaluated clinically after a face‐to‐face or telephone interview assessing the FA history, including recent symptoms and consumption (last 3 months) of core foods. The list of core foods should be defined while planning a study and may include typical, frequent and/or clinically relevant food‐allergen sources. For the multitude of foods not on this list, the consumption history is only recorded in case of earlier problems. This means there is no information on the number of people who ate the food recently, thus tolerating it. Without a robust estimate for the number of tolerant individuals, valid estimates of disease frequency cannot be calculated. These foods can therefore only be evaluated and reported on a descriptive case‐by‐case basis.

At first, a skin prick test (SPT) 14, or specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) testing for all a priori defined core foods, additionally relevant foods and potential sources of cross‐reacting aeroallergens (e.g. grass pollen, birch pollen) should be performed to determine sensitization. The reagents used for SPTs in a research project should be described in detail (e.g. fresh foods, commercial extracts, the latter were used in the EuroPrevall/iFAAM birth cohort). Similarly, the method for measuring allergen‐specific IgE should be specified. The physician's appraisal of whether the patient is allergic to the foods in question, just based on the interview/conversation, can be used as an additional study end point (‘Do you, as the physician, think that the reported history is suggestive of prior and/or current food allergy/hypersensitivity?’ (1) Yes, very likely (2) Possibly (I would evaluate further) (3) Possibly (but I would NOT evaluate further) (4) No, unlikely). This question is explained further by the following examples: (1) plausible history of repeated reactions or prior anaphylaxis (2) single reaction followed by avoidance or symptoms not always associated with food (3) vague history or no plausible link to ingestion (4) never experienced a reaction or the history is incompatible with food hypersensitivity. This item can serve as a proxy outcome for those eligible but refusing challenge testing.

Eligibility for oral food challenge

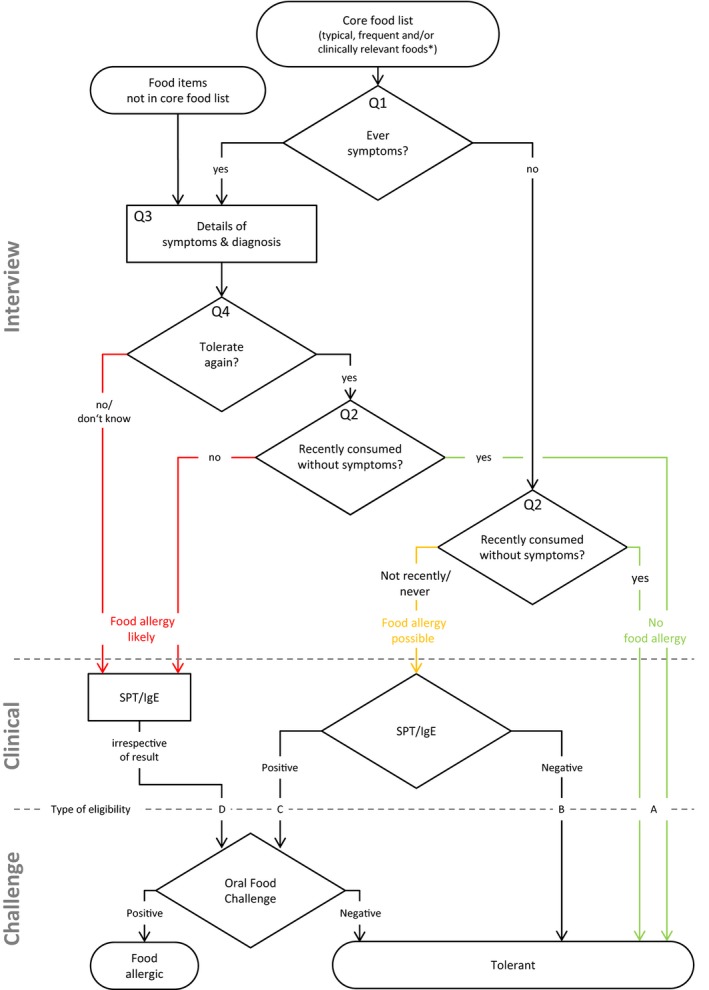

The decision whether suspected FA is confirmed or ruled out through a DBPCFC should be based on information from the interview/questionnaire assessment and the allergic sensitization status (e.g. SPT wheal diameter ≥3 mm or specific IgE levels ≥0.35 kU/l), following the outlined decision algorithm (decision tree, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Decision tree used to determine eligibility for an oral food challenge. Question numbers (e.g. Q1) refer to items used in the interview. SPT, skin prick test; IgE, Immunoglobulin E. *Only for these foods, a valid estimate for disease frequency can be calculated.

Food allergy is very unlikely, and a person does not need to undergo an oral food challenge if they have either eaten the food recently (in the last 3 months) without symptoms (eligibility type A), or have not eaten it recently but never had symptoms and are not sensitized (type B, Table 1).

Table 1.

| Type of eligibility | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questions 2/5: Have you/Has your child eaten [FOOD NAME] recently (within the last 3 months) without symptoms? | Yes | No | No | No |

| Question 1: Have you/Has your child ever had an illness or trouble caused by eating [FOOD NAME] or even a diagnosis of food allergy? | * | No | No | Yes |

| Sensitization | * | Negative SPT/IgE | Positive or missing SPT/IgE | * |

| Eligible for oral food challenge | No | No | Yes | Yes |

SPT, skin prick test; IgE, Immunoglobulin E. *information not needed for eligibility decision

In research, there are two indications for an oral food challenge: if a person is sensitized and if a food in question has not been eaten in the last 3 months without symptoms or the food was never consumed at all. This is necessary to screen yet unnoticed FA allowing estimation of FA prevalence (type C). If a person has had symptoms after eating a specific food at any time in their life and has either never tolerated it again or has tolerated it at some point but has not consumed it recently without symptoms, then a DBPCFC should be conducted to establish the current status of FA, regardless of the allergic sensitization status (type D, Table 1). There may be contraindications like a plausible report of recent anaphylaxis.

In all research settings, the type of eligibility (A–D) should be recorded for each food in question to allow better interpretation and comparability between study physicians, centres and studies.

Oral food challenge conduct and documentation

To reduce the overall number of challenge days and thus increase compliance, foods are grouped based on a common matrix used for blinding, herein called challenge blocks. For example, cow's milk and hen's egg powder can be blinded in the same matrix and thus be assessed on separate days within a single challenge block. For each of these blocks, only one placebo day needs to be scheduled and used as the reference for up to the maximum number of verum days (e.g. three), instead of one placebo day for each verum day.

To ensure also blinding of the staff attending the procedure, the dietician preparing the challenge meal shuffles the order of food allergens and placebo within a challenge block randomly, for example using a randomization list. The assignment of food allergens/placebo to actual challenge days is kept secret until finishing the whole challenge block, unless emergency unblinding is required.

All observations made on a challenge day can be documented in the challenge day form (Fig. 2). The DBPCFC schedules are typically comprised of 7–9 escalating doses, usually in intervals of 20–30 min. Signs and symptoms should be recorded in relation to the last dose consumed, specifying the exact time at onset of skin, respiratory, gastrointestinal, neurological or cardiovascular symptoms. The attending physician is asked to report symptom severity based on suggestions by the PRACTALL consensus report 1. For example, number of hives, number of episodes of vomiting and diarrhoea, impact and duration of scratching, or the area affected by rash are recorded.

Figure 2.

Documentation form for signs and symptoms observed during oral food challenges.

Symptoms within the last 24 h before the challenge day are recorded to differentiate between newly occurring and pre‐existing or recurrent symptoms. Objective parameters (blood pressure, pulmonary function) can be assessed and documented if considered necessary, for example based on prior reactions or safety concerns. The challenge is stopped upon predetermined criteria such as vomiting or urticaria (highlighted as orange and red symptoms in the form, Fig. 2). However, the final decision to stop the procedure is always at the discretion of the attending physician. After a stopped challenge or reaching the final dose as scheduled, the patient remains under clinical observation for at least 2 h. Symptoms occurring up to 24 h after the last dose can be recorded as an indicator of a delayed reaction. Therefore, final appraisal of the challenge day is deferred until then. An SOP for using the documentation form (Fig. 2) is available online (open access online supplement, updated versions and other languages at www.diagnosing-food-allergy.org).

Each DBPCFC day (placebo and verum separately) is rated negative if all planned doses were given with no clinical signs/symptoms or if observed signs/symptoms are not thought to be caused by the test food. It is rated positive if (objective) clinical signs or symptoms in relation to the tested food item occur – as proposed by Vlieg‐Boerstra and later adapted by Sampson 1, 15. In addition to these two categories, we suggest to define a challenge day as inconclusive if the reported signs/symptoms are not clearly attributable to the assessed food item (e.g. if similar signs/symptoms were reported earlier) or if a challenge day was stopped before reaching the final dose without ingestion‐related signs/symptoms.

Additionally, study physicians document their reasons leading to the final conclusion. The form requires the clinician to subjectively appraise the severity of the reactions on a scale from 0 to 10: firstly, based on just the signs and symptoms; secondly, including the length of exposure‐reaction intervals, necessity of medical interventions and other information from the medical history or observation of the procedure; and thirdly, from the patient's (or parent's) perspective. This information allows assessing potential heterogeneity in DBPCFC outcome decisions between individual study physicians in a single centre and between study centres in multicentre studies.

Negative food challenges should be confirmed by serving the cumulative full dose of allergen in a single meal on one of the following days 16.

Defining food allergy

Food allergy is usually handled as a dichotomous state: either food allergic or food tolerant 15. In clinical practice, physicians see a whole spectrum of reactions, from distress, self‐reported symptoms to mild or stronger objective clinical signs, and up to potentially fatal reactions. Splitting this originally continuous (and multidimensional) outcome into a dichotomous decision of being allergic or tolerant is often necessary to give dietary advice. However, it not only discards valuable information but also requires a clear cutoff that is agreed‐on and applied by different physicians to be useful in (comparative) research.

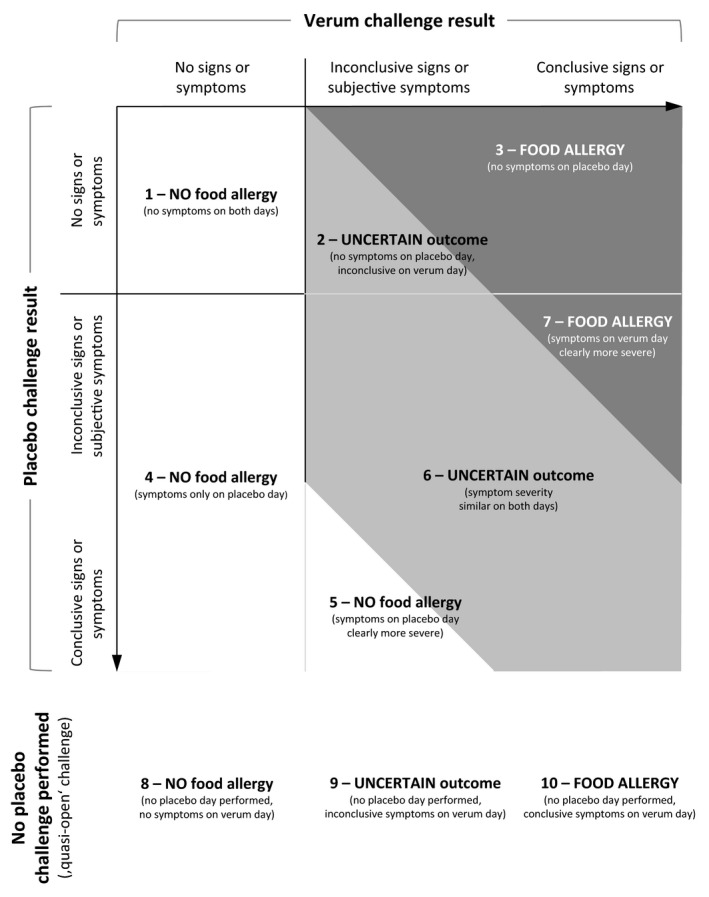

Recording graded signs and symptoms and semi‐quantitative perceived severity allows modelling of challenge day outcomes in a continuous fashion. Now, when judging the overall status in the light of both a placebo and a verum challenge, physicians should be asked to classify FA status within 10 meaningful levels, separating three broad outcome categories: ‘NO food allergy’, ‘UNCERTAIN outcome’ and ‘FOOD ALLERGY’ (Fig. 3). This allows comparison of detailed outcome information and adjustment for systematic differences such as proportion of placebo reactors as an indicator of individual cutoffs for interpreting challenge symptoms. We encourage researchers and clinicians alike to use a similar terminology for DBPCFC outcome assessments, supporting combined data analyses across studies and allergy clinics. In clinical care, an UNCERTAIN outcome is not helpful for the patient and further diagnostic evaluation and follow‐up care may be needed.

Figure 3.

Food allergy outcomes: NO food allergy, UNCERTAIN outcome and FOOD ALLERGY. Based on symptom severity on placebo and verum day.

Discussion

We developed a framework for a harmonized diagnosis of food allergies in population‐based and clinical research as part of the EU‐funded iFAAM project, based on experiences from the EuroPrevall project, and previously developed standards 1, 15. The follow‐up of the iFAAM/EuroPrevall birth cohort applied our protocol and decision algorithm. This diagnostic toolbox pioneers a generic questionnaire and interview items specifically on previous and current food allergies, in addition to the widely used set of allergy‐related questions in interviews and questionnaires 17.

Based on a physician‐administered interview and allergic sensitization tests, we developed a decision algorithm for eligibility to undergo DBPCFC tests, standardizing the triage for further diagnosis. Thorough documentation of the type of eligibility supports the extrapolation of frequency estimates for food allergies in the population. This will also allow taking account of challenge testing that is offered but declined or avoided. For example, one can use the proportion of positive DBPCFCs in individuals who became eligible when not eating a food and being sensitized, to estimate the number of undetected allergic individuals of those with the same eligibility criteria refusing challenge testing. The PRACTALL group stressed the need to grade signs and symptoms of food allergic reactions 1. Based on their consensus report and our evaluations of the multinational EuroPrevall birth cohort study up to age 2 18, 19, 20, we developed and piloted a generic one‐page form for the documentation of a complete food challenge day. This form will not only allow a grading of clinical signs and subjective symptoms, but also a specification of the exact time when signs and symptoms started, and will give an indication of subjective severity assessments of the reactions. If used in future projects, comparison between centres, studies and populations on the lowest sign‐ and symptom‐based level for a positive reaction will be possible. Furthermore, graded symptoms, subjective severity scoring and multilevel DBPCFC outcomes will improve comparability of physician‐specific sign/symptom cutoffs, often unconsciously applied by study staff for the definition of confirmed FA. It also allows the reporting of FA as a continuous phenomenon with mild to severe forms.

We introduce a more differentiated interpretation of DBPCFC outcomes based on verum and placebo days. From comparing symptom severity and conclusion between two challenge days, the allergy status is defined using a system of 10 different outcome levels, clustered into the three broad categories of NO food allergy, UNCERTAIN outcome and FOOD ALLERGY. For example, FOOD ALLERGY can be diagnosed through three different approaches: clear signs and symptoms on verum but none on placebo day, placebo signs and symptoms but less severe compared to verum day, or clear symptoms on verum day but no placebo challenge performed. Distinguishing these levels can inform the researcher about differences between projects and physicians and support estimation of the degree of individual diagnostic certainty. We will be able to validate the FA diagnosis internally as given by the study physician against different approaches of defining FA based on our detailed documentation of symptoms. Future validation including assessment of interobserver reliability will help identify areas for further improvement.

The overarching drawback of comparable and harmonized FA diagnosis is that it will always rely on physician's subjective appraisal of patient's/family's report of observed signs and symptoms of the patient. This cannot be overcome completely but a common standard for reporting, documentation and decision‐making can minimize limitations of subjective interpretations of blinded food challenges. Capturing subtle differences between physicians and settings might enable researchers to report or potentially adjust for individual factors and subjective perception. Beyond the generic SOPs we suggest here, IT‐supported decision‐making for eligibility, stop criteria or DBPCFC outcome judgment might be possible, but is complicated by the multidimensionality of input information and handling of rare exceptions, these are after all medical decisions. As FA is a very complex and heterogeneous condition, its investigation requires case definitions with a certain degree of complexity. The methods presented here tried to balance between ease of use and applicability on one side and capturing as much information as possible on the other. Our approach requires a thorough training and continued supervision to be consistently applied in research and clinical care alike.

Measuring incidence and prevalence of FA in population‐based research is subject to certain restrictions such as dietary habits in a population 21. Only if an individual (or parent) perceives a link between the ingestion of a specific food item and occurring symptoms can these be reported in the medical history. Without consuming a certain food, no reactions will ever be reported despite a patient having developed dormant allergy. This can be improved by applying allergic sensitization screening tests, but this approach will miss allergies to food items that are not included in the test battery and non‐IgE‐mediated reactions. To capture potential reactions, which would not be detected through SPT/IgE‐screening, every person not currently consuming food items in question would need to undergo a food challenge for all these. Such cases are not detected with the proposed algorithm. Therefore, prevalence can only be estimated validly for IgE‐mediated reactions. Furthermore, repeated assessments in the same cohort are needed for incidence and more informative prevalence estimates related to age at onset and screening for latent allergies 22, 23.

Conclusions

We developed a comprehensive toolbox for improved documentation and decision‐making using DBPCFC tests for FA diagnosis, particularly in population‐based epidemiological and clinical research settings. The toolbox may also facilitate decision‐making in clinical routine care, but has not yet been tested in this setting.

The presented methods have been applied in the EU‐funded iFAAM project as part of the school‐age follow‐up of a multinational European birth cohort study. Case report forms and SOPs are available as publicly accessible supplements under Creative Commons licensing, and we encourage their use in research and clinical settings as well as their further evolution (Open Access online supplement). Translated, amended and updated versions are available online (www.diagnosing-food-allergy.org). These harmonized tools and methods foster comparability between study physicians and centres as well as between different studies including interventional studies, for example in the fields of immunotherapy and primary/secondary prevention of FA. Furthermore, they will help to evaluate regional prevalence time trends, temporal courses of food allergies within the same individuals, and support future meta‐analyses of individual participant data.

Author contributions

All authors participated in developing the concept, questionnaire and clinical protocol of the cohort's current follow‐up. Kirsten Beyer initiated the birth cohort and led the study together with Thomas Keil. Linus B Grabenhenrich and Andreas Reich drafted the protocol, the CRFs and the manuscript. All authors critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest and funding

All authors received funding from the European Union within the Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under Grant agreement no. 312147 (iFAAM). Kate Grimshaw received grant and travel support from the UK Food Standards Agency and has had consultant arrangements with and received payment for lectures from Nutricia Ltd. Barbara Ballmer‐Weber received personal fees from ThermoFisher. Nikolaos Papadopoulos was on the advisory board at Abbvie, Novartis, GSK, Faes Farma, BIOMAY and HAL; received consultancy fees from MEDA, Novartis, Menarini, ALK ABELLO, and CHIESI; was a speaker/chairperson for Faes Farma, Uriach, Novartis, Stallergenes, Abbvie, MEDA, and MSD; and received grants from NESTEC and MERCK SHARP & DOHME. Graham Roberts received a grant from the UK Food Standards Agency. Aline Sprikkelman received grants from Danone Research, Nutricia Netherlands, SHS (Liverpool), GSK, Astra Zeneca, Teva Pharma, Ivax, MSD, ThermoFisher, MEDA and FrieslandCampina. Ronald van Ree received personal consultancy fees from HAL Allergy BV. Kirsten Beyer received grants from Danone and DBV Technology and personal fees from Danone, Nestle, Aimmune, Meda Pharma, ALK and Bausch & Lomb outside the submitted work. All other authors declared no conflict of interests.

Supporting information

Data S1. Generic forms and SOPs for the assessment of food allergy.

Grabenhenrich LB, Reich A, Bellach J, Trendelenburg V, Sprikkelman AB, Roberts G, Grimshaw KEC, Sigurdardottir S, Kowalski ML, Papadopoulos NG, Quirce S, Dubakiene R, Niggemann B, Fernández‐Rivas M, Ballmer‐Weber B, van Ree R, Schnadt S, Mills ENC, Keil T, Beyer K. A new framework for the documentation and interpretation of oral food challenges in population‐based and clinical research. Allergy 2017; 72:453–461.

Edited by: Antonella Muraro

References

- 1. Sampson HA, Gerth van Wijk R, Bindslev‐Jensen C, Sicherer S, Teuber SS, Burks AW et al. Standardizing double‐blind, placebo‐controlled oral food challenges: American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology‐European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology PRACTALL consensus report. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130:1260–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nowak‐Wegrzyn A, Assa'ad AH, Bahna SL, Bock SA, Sicherer SH, Teuber SS. Work Group report: oral food challenge testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;6(Suppl):S365–S383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Niggemann B, Beyer K. Pitfalls in double‐blind, placebo‐controlled oral food challenges. Allergy 2007;62:729–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Niggemann B, Beyer K. Diagnosis of food allergy in children: toward a standardization of food challenge. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007;45:399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Skypala IJ, Venter C, Meyer R, deJong NW, Fox AT, Groetch M et al. The development of a standardised diet history tool to support the diagnosis of food allergy. Clin Transl Allergy 2015;5:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muraro A, Werfel T, Hoffmann‐Sommergruber K, Roberts G, Beyer K, Bindslev‐Jensen C et al. EAACI food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines: diagnosis and management of food allergy. Allergy 2014;69:1008–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keil T, McBride D, Grimshaw K, Niggemann B, Xepapadaki P, Zannikos K et al. The multinational birth cohort of EuroPrevall: background, aims and methods. Allergy 2009;65:482–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McBride D, Keil T, Grabenhenrich L, Dubakiene R, Drasutiene G, Fiocchi A et al. The EuroPrevall birth cohort study on food allergy: baseline characteristics of 12,000 newborns and their families from nine European countries. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2012;23:230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feeney M, Marrs T, Lack G, Du Toit G. Oral food challenges: the design must reflect the clinical question. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2015;15:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nwaru BI, Hickstein L, Panesar SS, Muraro A, Werfel T, Cardona V et al. The epidemiology of food allergy in Europe: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Allergy 2014;69:62–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gellerstedt M, Magnusson J, Grajo U, Ahlstedt S, Bengtsson U. Interpretation of subjective symptoms in double‐blind placebo‐controlled food challenges – interobserver reliability. Allergy 2004;59:354–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brand PL, Landzaat‐Berghuizen MA. Differences between observers in interpreting double‐blind placebo‐controlled food challenges: a randomized trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2014;25:755–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Erp FC, Knulst AC, Meijer Y, Gabriele C, van der Ent CK. Standardized food challenges are subject to variability in interpretation of clinical symptoms. Clin Transl Allergy 2014;4:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heinzerling L, Mari A, Bergmann KC, Bresciani M, Burbach G, Darsow U et al. The skin prick test – European standards. Clin Transl Allergy 2013;3:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vlieg‐Boerstra BJ, van der Heide S, Bijleveld CM, Kukler J, Duiverman EJ, Dubois AE. Placebo reactions in double‐blind, placebo‐controlled food challenges in children. Allergy 2007;62:905–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Niggemann B, Lange L, Finger A, Ziegert M, Muller V, Beyer K. Accurate oral food challenge requires a cumulative dose on a subsequent day. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130:261–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, Beasley R, Crane J, Martinez F et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J 1995;8:483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xepapadaki P, Fiocchi A, Grabenhenrich L, Roberts G, Grimshaw KE, Fiandor A et al. Incidence and natural history of hen's egg allergy in the first 2 years of life – the EuroPrevall birth cohort study. Allergy 2015;71:350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schoemaker AA, Sprikkelman AB, Grimshaw KE, Roberts G, Grabenhenrich L, Rosenfeld L et al. Incidence and natural history of challenge‐proven cow's milk allergy in European children–EuroPrevall birth cohort. Allergy 2015;70:963–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eckers N, Grabenhenrich L, McBride D, Gough H, Reich A, Rosenfeld L et al. Frequency and development of hen's egg allergy in early childhood in Germany: the EuroPrevall birth cohort. Allergologie 2015;38:507–515. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oliver EM, Grimshaw KE, Schoemaker AA, Keil T, McBride D, Sprikkelman AB et al. Dietary habits and supplement use in relation to national pregnancy recommendations: data from the EuroPrevall birth cohort. Matern Child Health J 2014;18:2408–2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sicherer SH. Epidemiology of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:291–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Generic forms and SOPs for the assessment of food allergy.