Abstract

Objective

Retention in HIV care, particularly among postpartum women, is a challenge to national antiretroviral therapy (ART) programs. Retention estimates may be underestimated due to unreported transfers. We explored mobility and clinic switching among patients considered lost to follow-up (LTFU).

Design

Observational cohort study.

Methods

Of 788 women initiating ART during pregnancy at six public clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa, 300 (38.1%) were LTFU (no visit ≥3 months). We manually searched for these women in the South African National Health Laboratory Services database to assess continuity of HIV care. We used geographic information systems tools to map mobility to new facilities.

Results

Over one–third (37.6%) of women showed evidence of continued HIV care after LTFU. Of these, 67.0% continued care in the same province as the origin clinic. Compared to those who traveled outside of the province for care, these same-province “clinic shoppers” stayed out-of-care longer [median 373 days (IQR: 175–790) vs. 175.5 days (IQR: 74–371)] and had a lower CD4+ cell count upon re-entry [median 327 cells/µL (IQR: 196–576) vs. 493 cells/µL (IQR: 213–557). When considering all women with additional evidence of care as engaged in care, cohort LTFU dropped from 38.1% to 25.0%.

Conclusions

We found evidence of continued care after LTFU and identified local and national clinic mobility among postpartum women. Laboratory records do not show all clinic visits and manual matching may have been under- or overestimated. A national health database linked to a unique identifier is necessary to improve reporting and patient care among highly mobile populations.

Keywords: Retention, HIV/AIDS, South Africa, pregnancy, geographic information systems (GIS), migration

Introduction

South Africa’s government launched a universal test-and-treat policy to provide antiretroviral therapy (ART) to all HIV-positive people – regardless of CD4+ cell count – in September 2016.1 With more people living with HIV than any other country in the world, South Africa already had the largest ART program before this ambitious development.2 Expanded ART availability has altered dramatically the health and quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS, with an estimated life expectancy gain of 11.3 years between 2003 and 2011 due to ART3 and a 77% decrease in HIV transmission among serodiscordant couples.4 However, the rapid scale-up of the national ART program has put tremendous pressure on the limited resources of a public health sector that is hurrying to meet immense need. The positive impact of life expectancy gains and improved health through expanded ART availability will only be realized if eligible individuals access care, remain in care and adhere to treatment.

Despite widespread availability of ART, approximately 162,445 people died of AIDS in South Africa in 2015, representing nearly one–third of the country’s total deaths.5 Many of these deaths could have been avoided through earlier engagement and improved retention in HIV care. The problem of patient drop-out, or loss to follow-up (LTFU), within the public-sector in South Africa has been well documented.6,7 A large collaborative analysis of eight cohorts initiating ART across South Africa found that patient drop-out increased with duration on treatment, and by 36 months, 29% were LTFU.6 However, misclassification of retention outcomes likely clouds our understanding of the true magnitude of LTFU. As with much of sub-Saharan Africa, HIV care in most of South Africa is provided in decentralized clinics; patient data typically are captured first on paper files then later entered electronically into database programs. No unique patient identifier is used. As a result, when patients move between facilities, due to the highly mobile nature of the population or local “clinic shopping,” patient data typically are not transferred to the new facility. Clinics are not yet fully equipped to track patient movement from one facility to another, so a LTFU patient may actually be engaged in care elsewhere. Therefore, estimates of LTFU typically represent patient drop-out only from the perspective of a single clinic rather than system-wide retention, a serious limitation. Work in Uganda tracking a sample of patients considered lost has shown that retention estimates were underestimated by “silent transfers” (transfers not reported to the sending facility) between clinics and by unreported mortality.8–12 However, manually tracing patients is resource intensive, difficult to bring to scale, and usually relies upon self-reported retention.

Access to ART for all HIV-positive pregnant women through Option B+, introduced in South Africa in 2015,13 has helped to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV to the point where near-elimination is now thought possible.14 Despite this astounding achievement, there is mounting evidence that women who initiate ART during pregnancy may be at very high risk of LTFU,15–18 with re-engagement in routine HIV care after delivery a particular concern.19,20 Suggested reasons for this high LTFU include a lack of perception of need for treatment,16,21 increased financial burden,16,22 and stigma.23–26 In our recent work, we have observed that HIV-positive women reported difficulty in providing a “valid reason” to be seen at a clinic after giving birth; while pregnant, clinic attendance is accepted, but after delivery, clinic attendance and medication adherence are viewed with societal and familial suspicion.27 Additionally, postpartum women in South Africa may be a particularly mobile group, due in part to a tradition of returning to one’s rural home after delivery to receive care from family members.16,24,28 We wished to explore how women travel and access care during the peripartum period, which is characterized by frequent mobility.

While frequent population mobility in South Africa is known to contribute to the spread of HIV29,30 and is theorized to minimize the gains of ART as prevention,31 its impact on both patient care and programmatic estimates of retention in care is poorly understood. Better estimates of retention in HIV care would allow for resources to be targeted where they are most needed. Because South Africa does not have a national HIV database that allows tracking patients across treatment sites, but does have a national provider of laboratory services, we developed a novel method for tracking movement between HIV clinics and used an existing laboratory database to determine the continuity of HIV care and the frequency of clinic switching among postpartum women considered LTFU in South Africa. We then used geographic information system (GIS) mapping techniques to describe mobility among women seeking continued care.

Methods

Study population

To determine the proportion of women who continued HIV care after being considered LTFU, we conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the Right to Care (RTC) Clinical HIV cohort stored in an electronic database called TherapyEdge-HIV™. The database contains information on all routine clinical care for HIV-positive patients at participating public health clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa. Data are maintained and provided by the Health Economics and Epidemiology Research Office (HE2RO) in Johannesburg. At six Johannesburg public health clinics supported by Right to Care, 788 HIV-positive women initiated ART during pregnancy from January 1, 2012 – July 31, 2013. At this time, national guidelines called for initiation of lifelong ART for pregnant women with CD4+ cell counts ≤350 cells/µl. Of these 788 women, 300 (38.1%) were considered lost to follow-up by August 2015, defined as no clinic visit ≥3 months after the last scheduled visit; these 300 comprised our study population.

Patient tracing

The South African National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) conducts nearly all laboratory testing within the public sector HIV treatment program throughout the country and keeps a database of all lab results within a central data warehouse. While not a formal research database, patient results can be queried. To determine whether women initiating ART at a RTC-supported clinic received care after being lost to follow up, we manually traced these 300 women in the NHLS database using two methods. First, in September 2015, we searched using the query tool of the NHLS TrakCare Lab online website, which is available to clinicians and researchers via secure log-in. Each woman was queried a minimum of five times using combinations of full and/or partial name(s), surname and date of birth (DOB). Second, we searched for all 300 women again in the complete NHLS National HIV Cohort, using a probabilistic Jaro-Winkler matching algorithm for name and surname set to a minimum match probability of 91%, using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), followed by manually matching on exact DOB.

Outcome definitions

When NHLS records were found, we categorized the facility where a given lab record was ordered as being either the origin clinic – where ART was initiated – or a new destination facility. Starting with the date last seen at the origin clinic, we defined continued HIV care as accessing care at a new facility at any time during the follow-up period, as demonstrated by: a) at least one CD4 or viral load test on record, or b) any record from a new ART clinic, as shown by the facility name on the lab report.

Analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized using counts and proportions for categorical variables; medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous data. To assess patterns of movement between clinics, decimal degree coordinates were obtained for each facility where a woman received care by NHLS records or by query on Google Maps. Using ArcMap® 10.3.1 (Esri, Inc., Redlands, CA), the coordinates were imported to shapefiles with a WGS 1984 coordinate system. We connected origin and destination facilities using ArcMap’s XY-to-line tool, and distance between the origin and destination facilities was calculated by using an online tool (The Great Circle Calculator by Ed Williams, Williams.best.vwh.net/gccalc.htm) to compare the X/Y coordinates.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University and the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand.

Results

Patient characteristics of the 300 women who were considered LTFU after initiating antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy at six HIV clinics in Johannesburg are shown in Table 1. Median age and CD4+ cell count at ART initiation was 28.6 years (IQR: 24.8 – 32.7) and 267 cells/µL (IQR: 197 – 334), respectively. Nearly one–third were not self-identified South African nationals. The median time between ART initiation and the last clinic visit at the initiation site was about 3 months (104 days, IQR: 28 – 251).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants (n=300)

| Patient characteristic | Total |

|---|---|

| Age at ART initiation, median (IQR) | 28.6 (24.8–32.7) |

| Age at ART initiation, n (%) | |

| Younger than 25 years | 82 (27.3) |

| 25–32 years | 149(49.7) |

| 33 years and older | 69 (23.0) |

| CD4+ cell count at ART initiation (cells/µL), median (IQR) | 267 (197–334) |

| CD4+ cell count at ART initiation, n (%) | |

| Less than 200 cells/µL | 65 (21.7) |

| 200–350 cells/µL | 137 (45.7) |

| Over 350 cells/µL | 57 (19.0) |

| Missing | 41 (13.7) |

| Nationality, n (%) | |

| South Africa | 207 (69.0) |

| Outside of South Africa | 89 (29.7) |

| Missing | 4 (1.33) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Employed | 103 (34.3) |

| Not employed | 161 (53.7) |

| Missing | 36 (12.0) |

| Highest level of education attained | |

| Primary school or less | 20 (6.7) |

| Some secondary school | 140 (46.7) |

| Completed secondary school | 101 (33.7) |

| Missing | 39 (13.0) |

IQR, interquartile range

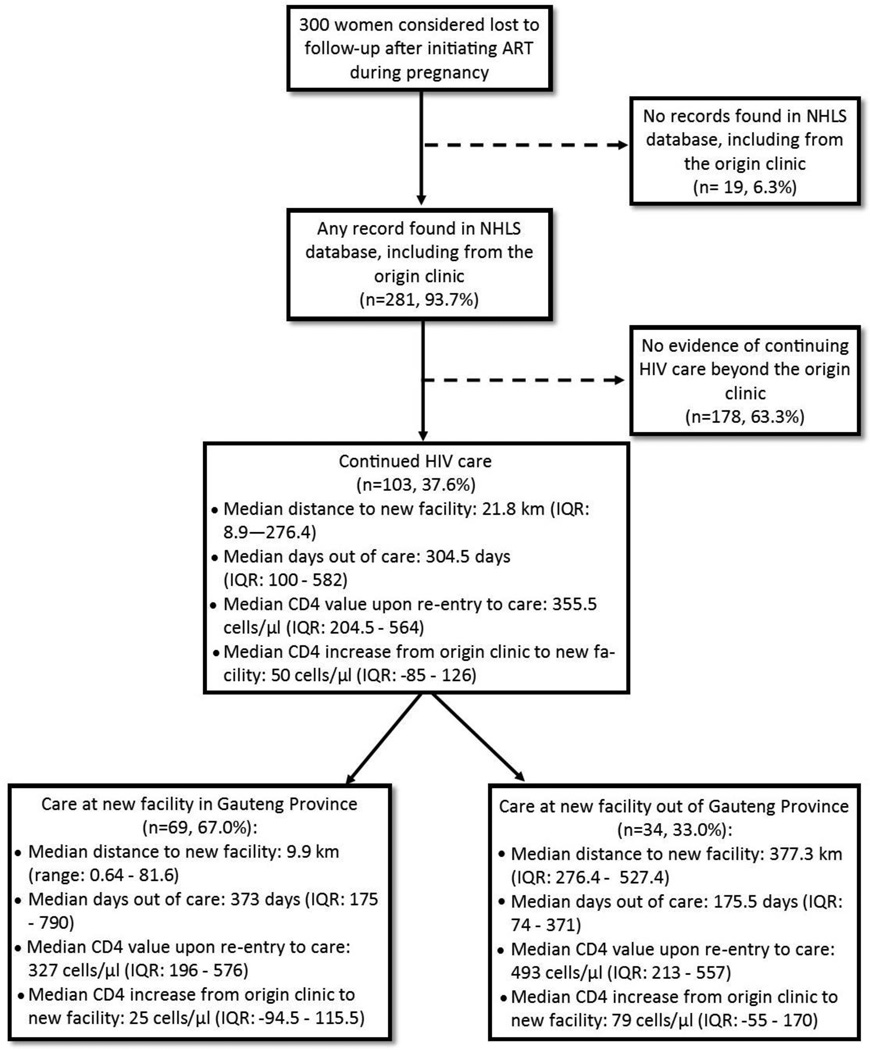

Figure 1 shows the results of tracing women in the NHLS database. We found at least one record – including from the origin clinic – for nearly all women (93.7%). Of these, over one–third (37.6%) showed evidence of continued HIV care. If we consider all 103 women with a subsequent lab record as engaged in care, LTFU in the original cohort of 788 pregnant women initiating ART drops from 38.1% (95%CI: 34.7 – 41.5%) to 25.0% (95%CI: 22.1% – 28.1%).

Figure 1.

Results of tracing patients considered lost to follow-up (n=300)

Among the 103 who continued HIV care, the median time out of care was 304.5 days (IQR: 100 – 582) and median CD4 upon reentry to care was 355.5 cells/µL (IQR: 204.5 – 564) (Figure 1). Overall, CD4 values from the last origin clinic visit and the first visit at the new facility were nearly unchanged, with a median increase of 50 cells/µL (IQR: −85 – 126). Viral load results from the new facility were available for 42/103 women (40.8%); of these, 24 (57.1%) were virally suppressed per South African treatment guidelines (<50 copies/mL),13 11 (26.2%) had viral loads 50–1000 copies/mL and 7 (16.7%) had >1000 copies/mL.

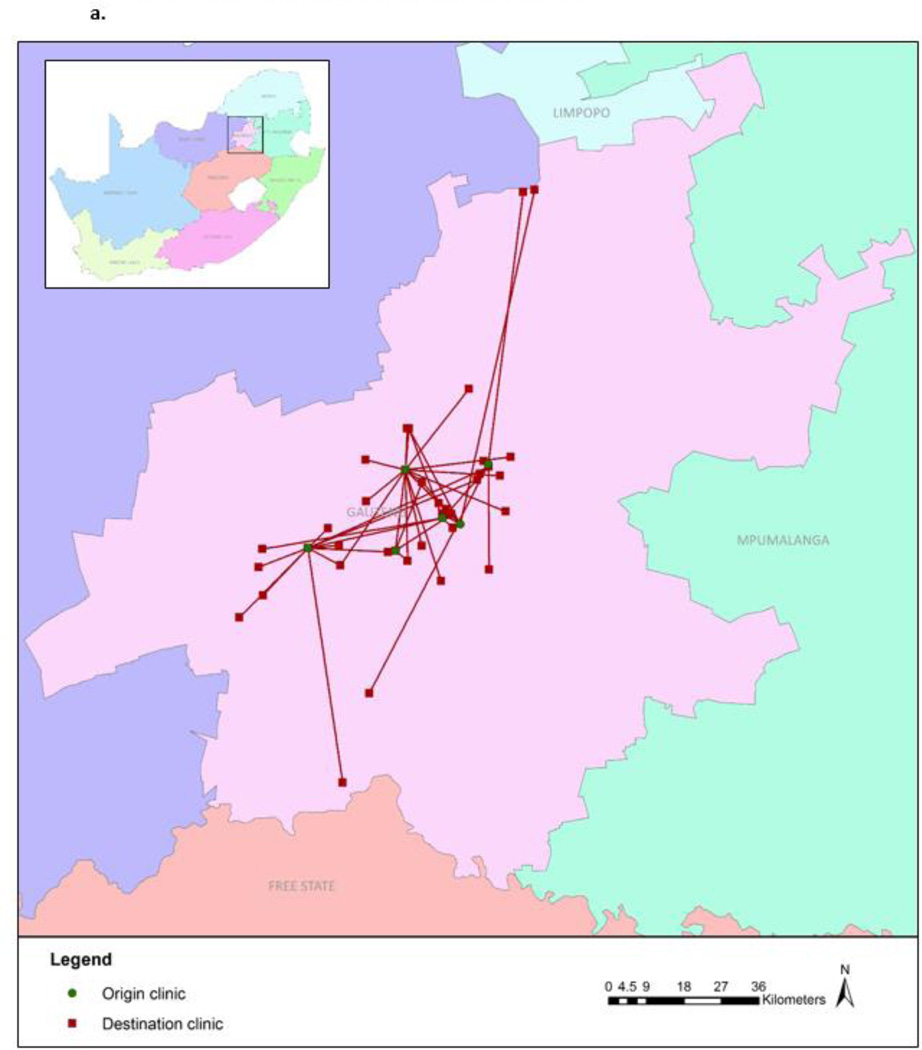

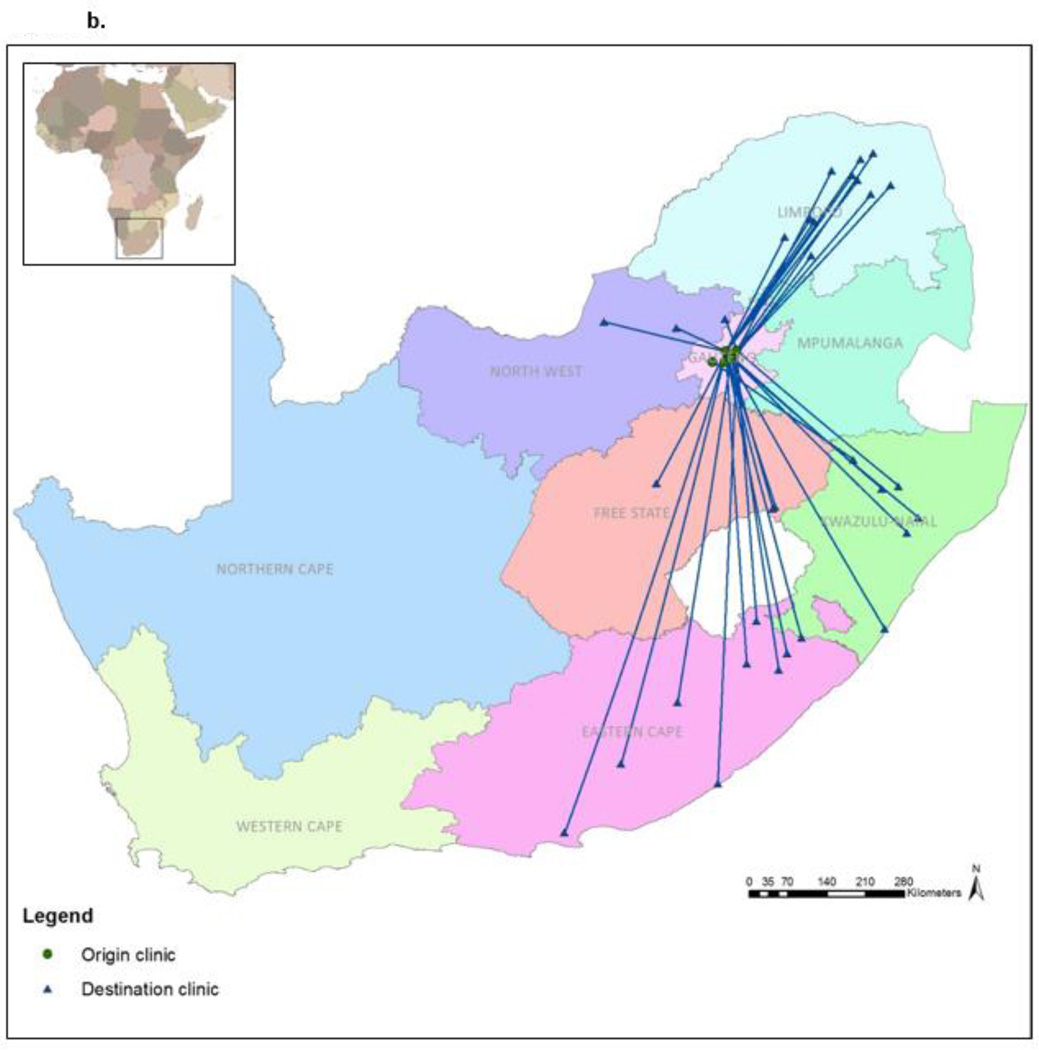

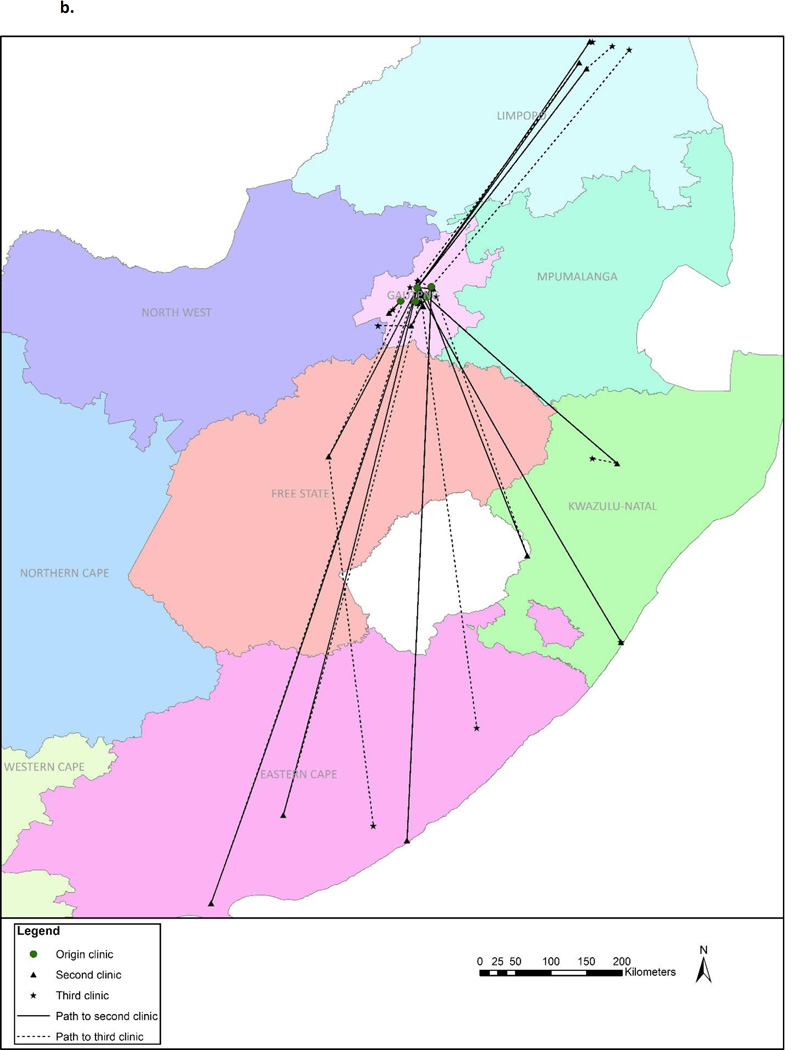

Figures 2a and 2b illustrate the movement between the origin and new facilities. Median distance between the origin and new facility was 21.8 km (IQR: 8.9 – 276.4). Two–thirds (67.0%) of the 103 women who continued HIV care did so in Gauteng Province – the same province as the origin clinic – with a median distance of 9.9 km (range: 0.6 – 81.6) between facilities (Figure 2a). For the remaining 33% who continued care elsewhere in South Africa, the median distance between facilities was 376 km (276 – 527) (Figure 2b). Women who visited a new facility within Gauteng Province stayed out of care longer (median 373.0 days vs. 175.5 days) and their median CD4 values upon return were lower (327 vs. 493 cells/µL) than those who sought care elsewhere in South Africa (Figure 1). Those who continued care outside of Gauteng Province had a greater CD4 increase (median 79 cells/µL; IQR: −55 – 170) upon re-entering care than those who sought care within Gauteng (median: 25 cells/µL; IQR: −94.5 – 115.5).

Figure 2.

a. Movement to facilities within Gauteng Province (n=69)

b. Movement to facilities outside of Gauteng Province (n=34)

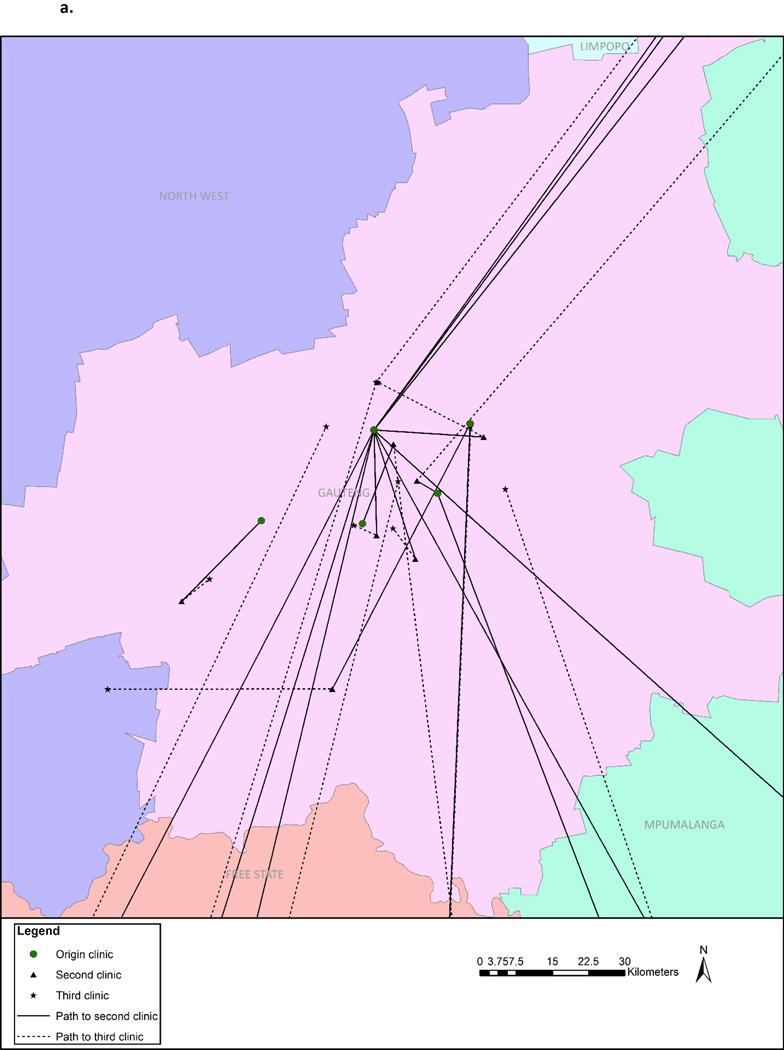

Our analysis also found further movement beyond just the first new facility. Overall, 103 (37.6%) women accessed at least one new facility, 18 (6.4%) accessed two or more, 6 (2.1%) accessed three or more, and 2 (0.7%) accessed four distinct facilities after dropping out of care from the origin site. Figures 3a and 3b display the movement of the 18 women who accessed at least two new clinics, showing that movement occurred both within Gauteng Province and to outside provinces.

Figure 3.

a. Movement to facilities within Gauteng Province by those attending two new facilities (n=18)

b. Movement to facilities outside of Gauteng Province by those attending two new facilities (n=18)

Discussion

We found substantial evidence of continued HIV care among women considered LTFU after initiating ART during pregnancy, both within the same city and in other provinces within South Africa. If we consider all of the 103 women who had records at a new clinic as engaged in care, LTFU in the original cohort drops substantially, from 38.1% to 25.0%, a 13% underestimation of retention in care. It is important to note that laboratory records are a limited proxy for retention, as they do not show the full picture of clinic visits, pharmacy pick-ups, or adherence, but we found evidence to suggest that current continuum of care estimates of retention may be overly pessimistic due to outcome misclassification. In our study, over one–third of women considered LTFU had accessed care at a new site, often referred to a “silent transfer”11 in retention research.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to spatially analyze movement between health care facilities. In doing so, we discovered that most women accessed care at a new facility close to where they initiated ART, while another one–third accessed care in a different province. We characterize those who accessed care close to their origin clinic as “clinic shoppers” and we were surprised to find that this group had poorer health outcomes upon returning to care than those who accessed care away from Johannesburg. This rather counterintuitive finding may be because women who traveled out of the province were more motivated to remain in care, or that those who returned to care in Gauteng Province had already traveled to a rural home after delivery and returned to care only upon resettling in Gauteng. It is also important to note that among a small sample, we found evidence of frequent clinic switching: two, three and four new facilities, both within Gauteng Province and outside, after seeming to drop out of the initiation site. Stigma, lack of purposeful disclosure, and fear of accidental disclosure have been identified as substantial barriers to retention in postpartum care,23,25–27 and the desire to seek anonymity may influence the decision to “shop” around to local facilities. Therefore, women in the “clinic shopper” group may have dropped out of care and delayed returning until sickness, then chose to return to a different clinic. Follow-up qualitative research to explore women’s mobility around the time of delivery and how it impacts retention in care and choice of facility is needed to better understand these quantitative findings. Our study demonstrated mobility among those who accessed care, but the mobility of women who did not access care is not represented; thus, the mobility within our study population – whether local, national or international – likely is higher than we found through tracing national lab records.

While we found evidence of continued HIV care, the outlook is still suboptimal. Women dropped out of care quickly after initiating ART – the median time from initiation visit to last clinic visit was just 3 months (104 days, IQR: 28–251) – which highlights the need for enhanced retention counseling given the expansion of ART through the universal test-and-treat policy. Even if we reclassify all 103 women with just one continued visit as engaged in care, 25% LTFU is still unacceptably high. All of the women in this cohort initiated ART during pregnancy; dropping out of care puts them at risk of immunosuppression and death, as well as transmission of the virus to the baby. Furthermore, we found that women are suspending care for extended periods of time before re-engaging, with CD4 counts remaining relatively low and viral loads increasing during the time out of care. This was most apparent in the group of “clinic shoppers” seeking alternative clinics in Gauteng Province, whose median time between lab tests was over a year (373 days, IQR: 175–790) despite eventually going to a new facility very close (median <10km) to where they started. Overall, fewer than half (40.3%) of those who accessed a new facility received a viral load test. Consistent retention in postpartum HIV care remains a substantial challenge in South Africa, both from an individual and a health systems perspective, and one that may be exacerbated by expansion of ART availability through Option B+ and test-and-treat policies.

This study adds to the small body of work within the sub-Saharan African region examining continued care among individuals considered lost to follow-up after ART initiation.11,32–34 Our study manually linked existing data sources to search for all lost patients, rather than physically tracing a sample of lost patients in the community. This method has advantages and disadvantages. One advantage is that we did not rely on patient-reported retention, which may be subject to bias, and when available, lab records contain extremely useful clinical data. Also, because clinicians in South Africa have access to NHLS’s web query tool, this method of patient tracing could be used to search national lab results in real-time during patient care. However, even if this were possible, given time and resource constraints, the manual searching of patients is cumbersome, requiring patience and diligence. For example, for a patient with the first name Beverly, we found matching records with five spellings: “Beverly,” “Beverley,” “Bereley,” “Bevelly” and “Bervely.” In addition to misspellings, we often encountered confusion between first and middle names, and date of birth transposing errors. Manually searching for lost patients took many hours and is more feasible as a research exercise than as a routine clinical follow-up. While we used two different techniques for matching records, it is possible that we still missed records or misclassified matches, resulting in either overmatching or undermatching. Also, due to differing periods of follow-up time, some participants had more time to meet the definition of continued in care than others.

An additional limitation is that lab records do not contain pregnancy information, so we do not know the timing of delivery and cannot determine the transition from antenatal to postpartum care. However, considering that the median time out care among women who continued care was over 300 days, we can assume that most were no longer pregnant with the index pregnancy. Death records also were unavailable, so ascertainment of death may be incomplete. Furthermore, lab records do not tell us why the patient accessed care – whether for a routine visit or otherwise – or the complete timeline of continued care, as a lab-based test may not have been completed at each visit. Additionally, almost 30% of our cohort self-identified nationality other than South African, but the lab database only contained records from within South Africa; thus, we cannot comment on cross-border mobility. For these reasons, we consider this work to be a proof-of-concept to demonstrate that women are continuing care after LTFU in the absence of a national, linked clinical database.

Our findings highlight the difficulty of producing accurate estimates of retention in care in the context of frequent mobility and clinic switching. This movement affects not only estimates of retention in care for epidemiologic research, but also real-world patient care since clinical data from other sites are unavailable in real time. We have demonstrated that patients are moving facilities, but unless a patient requests a formal transfer, their records do not move. As countries like South Africa weigh their future health care reporting systems, results like these emphasize the urgent need for a national database with improved data quality management, linked by a unique identifier to improve health services for a highly mobile population.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Jacob Bor at Boston University and Dr. Steven Wernke and Dr. Lauren Kohut at Vanderbilt University for their contributions to this work and acknowledge the National Health Laboratory Services for access to laboratory data.

Sources of funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01MH107256. HE2RO staff and Dr. Fox were supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) under Award Number R01AI115979 and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement AID 674-A-12-00029. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, USAID or the US Government.

Footnotes

Meetings:

Presented in part as poster 792 at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2016) and abstract 93 at the 20th International Workshop on HIV Observational Databases (IWHOD 2016).

Conflicts of interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Republic of South Africa Department of Health. Implementation of the Universal Test and Treat Strategy for HIV Positive Patients and Differentiated Care for Stable Patients. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2013. 2013

- 3.Bor J, Herbst AJ, Newell M-L, Bärnighausen T. Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science (80-) 2013;339(6122):961–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1230413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oldenburg CE, Bärnighausen T, Tanser F, et al. Antiretroviral therapy to prevent HIV acquisition in serodiscordant couples in a hyperendemic community in rural South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statistical Release: Mid-Year Population Estimates. Pretoria: 2015. Statistics South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornell M, Grimsrud A, Fairall L, et al. Temporal changes in programme outcomes among adult patients initiating antiretroviral therapy across South Africa, 2002–2007. AIDS. 2010;24(14):2263–2270. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833d45c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: systematic review. Trop Med Int Heal. 2010;15(Suppl 1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geng EH, Emenyonu N, Bwana MB, Glidden DV, Martin JN. Sampling-based approach to determining outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy scale-up programs in Africa. JAMA. 2008;300(5):506–507. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geng EH, Bangsberg DR, Musinguzi N, et al. Understanding reasons for and outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa through a sampling-based approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(3):405–411. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b843f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geng EH, Glidden DV, Emenyonu N, et al. Tracking a sample of patients lost to follow-up has a major impact on understanding determinants of survival in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Africa. Trop Med Int Heal. 2010;15(Suppl 1):63–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geng EH, Glidden DV, Bwana MB, et al. Retention in care and connection to care among HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Africa: estimation via a sampling-based approach. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geng EH, Glidden DV, Bangsberg DR, et al. A causal framework for understanding the effect of losses to follow-up on epidemiologic analyses in clinic-based cohorts: the case of HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Africa. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(10):1080–1087. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Republic of South Africa Department of Health. National Consolidated Guidelines for the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the Management of HIV in Children, Adolescents and Adults. Pretoria: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating Pregnant Women and Preventing HIV Infection in Infants: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. Geneva: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan R, Orrell C, Zwane E, Bekker L-G, Wood R. Loss to follow-up and mortality among pregnant women referred to a community clinic for antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 2008;22(13):1679–1681. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830ebcee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang B, Losina E, Stark R, et al. Loss to follow-up in a community clinic in South Africa--roles of gender, pregnancy and CD4 count. S Afr Med J. 2011;101(4):253–257. doi: 10.7196/samj.4078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myer L, Cornell M, Fox MP, et al. 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle, WA: Loss to follow-up and mortality among pregnant and non-pregnant women initiating ART: South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clouse K, Pettifor A, Maskew M, et al. Initiating antiretroviral therapy when presenting with higher CD4 cell counts results in reduced loss to follow-up in a resource-limited setting. AIDS. 2013;27(4):645–650. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835c12f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clouse K, Pettifor A, Shearer K, et al. Loss to follow-up before and after delivery among women testing HIV positive during pregnancy in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Heal. 2013 doi: 10.1111/tmi.12072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Tomlinson M, Scheffler A, Le Roux IM. Re-engagement in HIV care among mothers living with HIV in South Africa over 36 months postbirth. AIDS. 2015 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solarin I, Black V. “They Told Me to Come Back”: Women’s Antenatal Care Booking Experience in Inner-City Johannesburg. Matern Child Heal J. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ngarina M, Popenoe R, Kilewo C, Biberfeld G, Ekstrom AM. Reasons for poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy postnatally in HIV-1 infected women treated for their own health: experiences from the Mitra Plus study in Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ngarina M, Tarimo EAM, Naburi H, et al. Women’s Preferences Regarding Infant or Maternal Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV during Breastfeeding and Their Views on Option B+ in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman RM, Black V, Technau K, et al. Effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy duration and regimen on risk for mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54(1):35–41. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181cf9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferguson L, Grant AD, Watson-Jones D, Kahawita T, Ong’ech JO, Ross DA. Linking women who test HIV-positive in pregnancy-related services to long-term HIV care and treatment services: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Heal. 2012;17(5):564–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorsen VC, Sundby J, Martinson F. Potential initiators of HIV-related stigmatization: ethical and programmatic challenges for PMTCT programs. Dev World Bioeth. 2008;8(1):43–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2008.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clouse K, Schwartz S, Van Rie A, Bassett J, Yende N, Pettifor A. “What they wanted was to give birth; nothing else”: Barriers to retention in Option B+ HIV care among postpartum women in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(1):e12–e18. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferguson L, Lewis J, Grant AD, et al. Patient attrition between diagnosis with HIV in pregnancy-related services and long-term HIV care and treatment services in Kenya: A retrospective study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(3):e90–e97. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318253258a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lurie MN, Williams BG, Zuma K, et al. Who infects whom? HIV-1 concordance and discordance among migrant and non-migrant couples in South Africa. AIDS. 2003;17(15):2245–2252. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200310170-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lurie MN, Williams BG, Zuma K, et al. The impact of migration on HIV-1 transmission in South Africa: a study of migrant and nonmigrant men and their partners. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30(2):149–156. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrews JR, Wood R, Bekker L-G, Middelkoop K, Walensky RP. Projecting the benefits of antiretroviral therapy for HIV prevention: the impact of population mobility and linkage to care. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(4):543–551. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brinkhof MWG, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hickey MD, Omollo D, Salmen CR, et al. Movement between facilities for HIV care among a mobile population in Kenya: transfer, loss to follow-up, and reengagement. AIDS Care. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1179253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tweya H, Gugsa S, Hosseinipour M, et al. Understanding factors, outcomes and reasons for loss to follow-up among women in Option B+ PMTCT programme in Lilongwe, Malawi. Trop Med Int Heal. 2014;19(11):1360–1366. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]