ABSTRACT

Since the initial reports that a group of small RNAs, now known as microRNAs (miRNAs), regulates gene expression without being translated into proteins, there has been an explosion of studies on these important expression modulators. Drosophila melanogaster has proven to be one of the most amenable animal models for investigations of miRNA biogenesis and gene regulatory activities. Here, we highlight the publicly available genetic tools and strategies for in vivo functional studies of miRNA activity in D. melanogaster. By coupling genetic approaches using available strain libraries with technologies for miRNA expression analysis and target and pathway prediction, researchers' ability to test functional activities of miRNAs in vivo is now greatly enhanced. We also comment on the tools that need to be developed to aid in comprehensive evaluation of Drosophila miRNA activities that impact traits of interest.

KEYWORDS: Drosophila melanogaster, genetics, in vivo, microRNA, tools

Introduction

miRNAs are small regulatory RNAs that range in size from ∼19–24 nucleotides and exert post-transcriptional effects on gene expression via complementary base pairing with target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) by either blocking translation or decreasing message stability in their roles as expression modulators. The discovery of the first miRNA came from the characterization of the heterochronic gene lin-4 in C. elegans,1 when it was found that lin-4 did not encode a protein product but post-transcriptionally repressed lin-14, potentially by binding to complementary sequences in the 3′untranslated region (UTR) of the lin-14 mRNA.2,3 As interesting as this serendipitous finding was, it was an anomaly to many and was considered a unique case, relevant in nematodes only, for lin-4 is not conserved beyond the Caenorhabditis genus.4 It took nearly another decade after the discovery of lin-4 RNA-mediated regulation of lin-14 for the scientific community to recognize that there were evolutionarily conserved instances of translational repression by endogenous small RNAs via antisense mechanisms.5 The major breakthrough came with the discovery of let-7, another non-coding RNA5 that was highly conserved across multiple species, including humans, zebrafish and fruit flies. These discoveries paved the way for investigating endogenous small RNA-mediated developmental control across animal taxa, and since then progress has been made by several groups in understanding the biogenesis pathways for miRNAs6 as well as their targeting mechanisms.7 Toward these efforts, D. melanogaster has proven to be one of the most amenable animal models for both in vitro and in vivo studies of miRNA biogenesis, expression and activity. The recent availability of a variety of genetic and molecular tools for manipulating D. melanogaster miRNA levels in vivo has greatly facilitated use of this animal model for miRNA functional analysis.

In vivo tools for studying miRNA functions

Among the key characteristics of D. melanogaster that make it a tractable model for in vivo studies are its relatively short developmental period and lifespan, its compact genome, and the reasonable ease with which researchers can manipulate gene expression in vivo. As a result of these features, D. melanogaster has proven to be a useful animal model for studying a wide variety of biologic processes, and researchers have developed genetic tools that allow manipulation of gene expression levels in vivo. There are a variety of strategies that can be used to generate gene-specific deletion mutations, strains are available for RNAi-mediated reduction of gene expression, and there are tools for overexpression and misexpression studies. The deletions and in vivo constructs for manipulating miRNA expression are maintained with balancer chromosomes that prevent recombination and have dominant markers that allow researchers to track alleles in progeny from genetic crosses. These strategies have been applied in recent years to the study of functional activities of miRNAs in specific cells and tissues in whole animals. The recent public availability of strain libraries that allow researchers to manipulate the expression levels of most Drosophila miRNAs makes it now possible for researchers to carry out large-scale screens to investigate the contributions of miRNA activity to any number of interesting biologic processes.

Deletion mutants

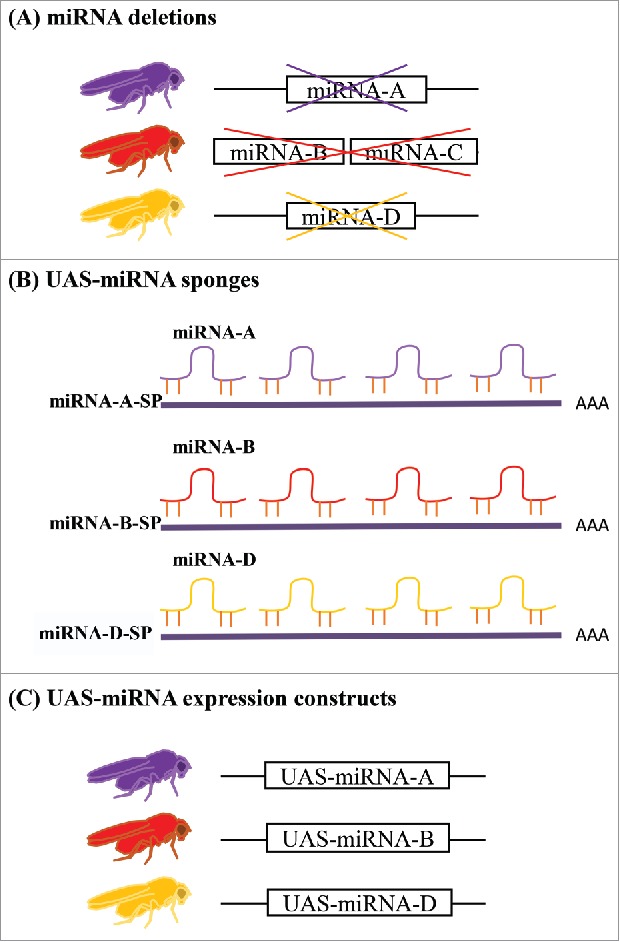

One important strategy in the Drosophila geneticist's toolkit is the ability to produce miRNA-specific deletion mutants. While several laboratories have created strains in which one miRNA or a cluster of nearby miRNAs is deleted, a more comprehensive library of 80 targeted miRNA knockout strains covering 104 miRNA genes was created by ends-out homologous recombination.8 miRBase (http://mirbase.org, release 21), a searchable online database for miRNA sequences in 223 species, identifies 256 miRNA precursors that are cleaved to produce 466 mature miRNAs in D. melanogaster. The combined set of strains deletes 130 of these miRNA-encoding loci either singly or in clusters (Fig. 1A) and is available at the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (http://fly.bio.indiana.edu/) (Table 1). Drosophila miRNAs expressed at very low levels or those that are not present in other taxa were not targeted for mutation because they were not expected to produce developmental phenotypes.8

Figure 1.

miRNA tools for in vivo studies. (A) Targeted deletions are available at public stock centers for 130 out of 256 miRNA loci in Drosophila. The loci were deleted either singly or in clusters. (B) UAS-miRNA sponges are available for reducing the activity of 141 independent miRNAs in specific tissues or cells. (C) UAS-miRNA expression constructs for use in misexpression, overexpression and mutant rescue experiments are also available for a subset of miRNAs. A, B, C and D are generic designations for Drosophila miRNAs.

Table 1.

Public repositories for Drosophila miRNA strains.

| Tool/Strain | Stock Center | No. of Strains | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA deletion | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center http://fly.bio.indiana.edu/ | 120 | Chen et al. 2014 |

| Kyoto Stock Center https://kyotofly.kit.jp | 90 | (and references within) | |

| UAS-miRNA | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center http://fly.bio.indiana.edu/ | 264 | Bejarano et al. 2012 |

| FlyORF http://flyorf.ch/index.php | 170 | Schertel et al. 2012 | |

| Kyoto Stock Center https://kyotofly.kit.jp | 154 | Szuplewski et al. 2012 | |

| UAS-miRNA-sponge | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center http://fly.bio.indiana.edu/ | 147 | Fulga et al. 2015 |

Phenotypic evaluation of the set of 130 strains revealed that few of the single miRNA deletion alleles cause lethality, indicating that they are not required for development.8 This result is not surprising given the observations that miRNAs are most often involved in fine tuning gene expression9 and that multiple miRNAs often work in concert to affect specific mRNA targets.9,10 Indeed, few individual miRNA mutants in C. elegans had phenotypic effects on either development or viability,11,12 although mutant effects were enhanced in sensitized genetic backgrounds.13

Mutant survival to adulthood provides an opportunity to examine adult phenotypes from miRNA knockout in many of these strains. Evaluation of stage-specific developmental survival and several adult phenotypes, including lifespan, hemolymph-brain barrier permeability, fertility and ovary morphology, demonstrated that greater than 80% of the miRNA deletion strains cause at least one phenotype. Generally, only the most highly expressed miRNAs produce phenotypes in mammalian cells,14,15 but Chen et al. identified only a few instances where phenotypic effects correlated with miRNA expression levels. In most cases the highly expressed Drosophila miRNAs affected development, causing lethal phenotypes before adulthood.8 Lack of correlation between phenotype and miRNA expression level in other instances may be a consequence of the fact that miRNA expression levels for these comparisons were evaluated in whole animals. It is plausible that other Drosophila miRNAs are tissue-specifically expressed at high levels and that this expression correlates with phenotypic effects in animals when the miRNAs are deleted.

Careful interpretation of miRNA contributions to adult phenotypes will require that adult-specific knockdown experiments are performed as well since systemically reduced miRNA activity throughout development may produce different effects than adult-specific reduction. Similarly, it is necessary to understand the effects from loss of individual miRNAs in specific tissues and cells, which cannot be evaluated with a blunt tool such as a traditional deletion mutant. At some point it will be important for researchers to create deletion mutations for the remaining poorly expressed and non-conserved miRNAs to investigate their functions, particularly the non-conserved miRNAs expressed at moderate-to-high levels that may be more likely to cause phenotypes.

General tools for miRNA overexpression or misexpression

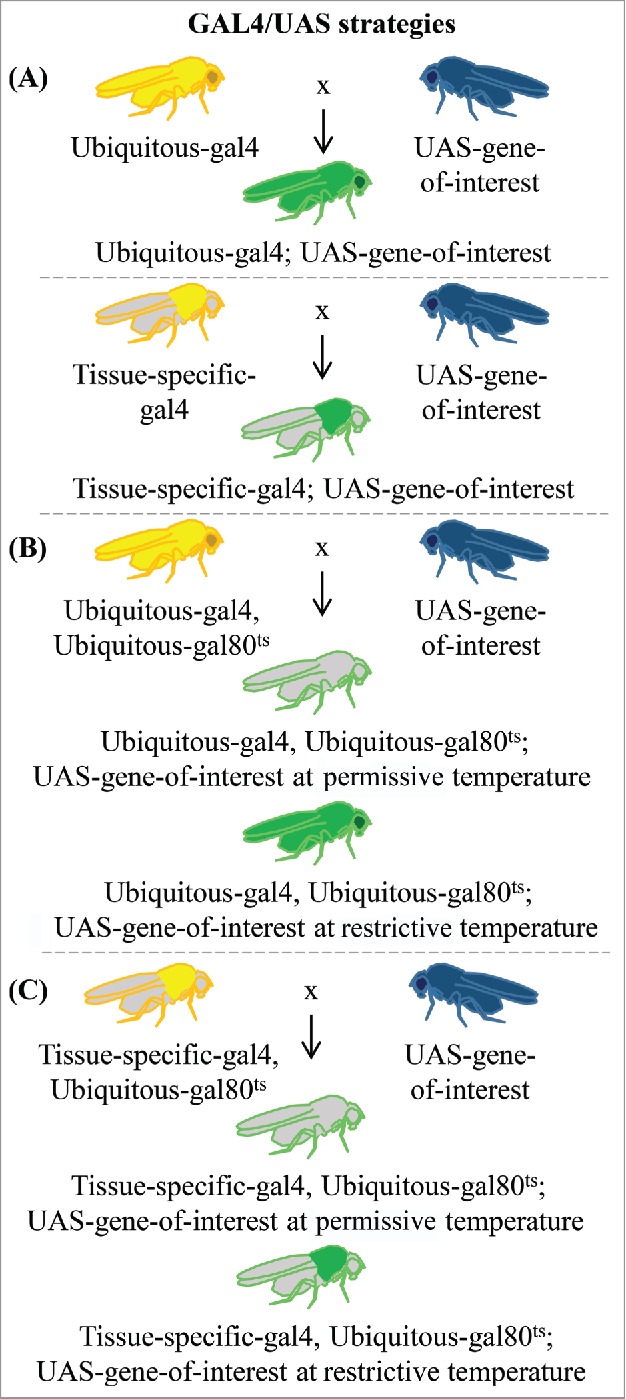

Beyond gene-specific loss-of-function mutations, one of the most useful tools available to Drosophila researchers studying in vivo gene activity is the GAL4/UAS system16 and related strategies. The GAL4/UAS system provides researchers with the ability to manipulate and control gene expression temporally and spatially within the animal. In short, the yeast GAL4 transcriptional activator is expressed under the control of a ubiquitous or tissue-specific enhancer (Fig. 2A) and can be used to activate expression of any gene that is cloned downstream of the UAS binding sites that specifically interact with the GAL4 protein. For example, it is possible to overexpress or misexpress genes ubiquitously when enhancers such as those for the actin and ubiquitin genes are used to control gal4 expression (e.g., actin-gal4 or ubi-gal4); tissue-specific enhancers can be used to limit GAL4 expression and, hence, gene-of-interest expression to desired tissues (Fig. 2A). The enhancer-gal4 and UAS-gene-of-interest constructs are maintained in separate strains until an experiment is initiated, when a simple genetic cross allows production of offspring that contain both constructs (enhancer-gal4/UAS-gene-of-interest) for phenotypic testing.

Figure 2.

Variations of the GAL4/UAS system in common use. (A) The GAL4/UAS system can be used to manipulate gene expression either ubiquitously or in a tissue-specific manner (illustrated in thoracic muscle as an example). Crosses between a strain carrying enhancer-gal4 (ubiquitous or tissue-specific enhancer) and a strain with the UAS-gene-of-interest (gene coding sequence, RNAi, miRNA-sponge, etc. represented in blue) produce flies containing both elements. In enhancer-gal4 parents and progeny, GAL4 is always expressed based on the activity of the enhancer (represented by yellow areas). In progeny from the cross, the UAS-gene-of-interest will be activated where GAL4 is present, either ubiquitously or restricted to the same tissue-specific regions as the enhancer (represented by green in the figure). (B) Temporal control of GAL4/UAS activity can be achieved by repression of GAL4 by Gal80ts which restricts activity at low temperatures (represented by gray areas) but is inactivated at higher temperatures, thereby allowing widespread expression of the gene of interest (green body). (C) Both temporal and spatial control of gene expression can be achieved by combining a tissue-specific enhancer-gal4 with Gal80ts (green thorax).

Enhancements to this GAL4/UAS system include the ability to introduce a temperature sensitive gal80 allele that can be used to control temporal expression of gal4.17 In this case, animals raised in the permissive temperature range of 19–22°C cannot activate GAL4-mediated gene expression. Increasing the temperature to 30°C inactivates GAL80ts, enabling GAL4-controlled gene expression to proceed (Fig. 2B, C). This strategy can be used to produce ubiquitous gene expression in a particular timeframe (Fig. 2B) depending on the timing of the heat application. For example, target gene expression can be induced at a specific developmental stage or during adulthood. Gene expression can be restricted both spatially and temporally if a tissue-specific enhancer is selected to express the gene-of-interest (Fig. 2C). Only cells capable of expressing the tissue-specific-gal4 construct will express the desired gene at the appropriate time. A related strategy, the GeneSwitch system, relies upon fusion of the hormone binding domain from a nuclear receptor, such as the progesterone receptor (PR), to the GAL4 DNA binding domain, thereby sequestering GAL4 in the cytoplasm. When PR is bound to the RU486 ligand, which is usually provided to the flies in a food source, the GAL4/PR/RU486 complex is transferred to the nucleus to initiate GAL4-medited gene expression in the desired location.17,18 See19 for a more detailed review of these and related strategies as well as modular expression options for expressing different UAS-gene-of-interest constructs in distinct cell populations.

miRNA sponges for reducing miRNA activity

As for protein-coding genes, the GAL4/UAS system can be used to express miRNA-encoding genes or to express RNAs that inhibit miRNA activity. Therefore, another important tool in the Drosophila arsenal for reducing miRNA activity in cells is a set of UAS-inducible strains that express miRNA “sponges” (Fig. 1B). These strains produce transcripts with repetitive sequences that are complementary to a specific miRNA, with the end goal of “soaking up” miRNAs through their interaction with the sponge sequence rather than the target mRNA, hence decreasing miRNA activity in cells.20,21 Therefore, any observed phenotypes resemble those of reduced function or loss-of-function mutations.

There is a publicly available set of Drosophila UAS-miRNA sponge alleles (Table 1) covering 141 miRNAs, most of which are closely related to human miRNAs.21 The UAS-miRNA-sponge (UAS-miRNA-SP) constructs consist of 20 copies of the appropriate miRNA complementary sequence cloned into the 3′ untranslated sequence of mCherry. Expression of mCherry allows visualization of the sponge expression pattern. The constructs were integrated at the attP40 (2nd chromosome) and attP2 (3rd chromosome) sites to reduce positional effects and equalize expression, yielding 282 independent strains. Comparisons of effects of miRNA null mutations8 to those from globally expressed UAS-miRNA-SP revealed general concordance between the null and miRNA sponge phenotypes, and miRNA sponge effects were dose dependent with strains containing identical sponge insertions on both chromosomes producing stronger effects.21 Similarly to analysis of knockout mutations,8 experiments using the miRNA sponges did not reveal strong correlations between miRNA expression levels and phenotypic effects from miRNA-sponge expression.21

Such miRNA-sponge strains are advantageous from the perspective that they can be used as a means for validating null mutant phenotypes as well as to probe tissue-specific and stage-specific activities of individual miRNAs or groups of miRNAs. For example, adult-specific reduction of miRNA activity can be achieved with the GAL80ts system (Fig. 2B), and the phenotypic effects can be compared with those that occur when the same miRNA is completely deleted. miRNA sensor strains allow researchers to monitor the effects of UAS-miRNA-SP or UAS-miRNA misexpression or overexpression (described below) through their effects on target gene 3′UTRs. These constructs function by expressing a cell autonomous marker sequence, such as GFP, fused to a 3′UTR derived from a gene known to be regulated by a specific miRNA. Successful miRNA-mediated inhibition is indicated by a decrease in GFP expression.21,22 Currently, sensors are not available for all miRNAs, and many more will need to be developed to meet the needs of specific investigators. Moving forward, it also will be important for additional sponge strains to be created that are specific to the remaining miRNAs so their functions can be determined.

miRNA tools for overexpression or misexpression

Several groups have created large-scale libraries of UAS-miRNA strains that allow over- and misexpression of miRNAs (Fig. 1C) as a complementary strategy to analyzing miRNA loss-of-function or reduced function effects.22–24 Such controlled miRNA expression has several applications. It can be used to rescue knockout mutants by expressing the miRNAs in deletion backgrounds, providing a means to verify that phenotypes identified from knockout mutations are due to deletion of the miRNA in question. While researchers often use a globally expressed enhancer-gal4, such as tubulin-gal4 or actin-gal4, for rescue experiments, selection of spatially limited enhancer-gal4 constructs allows researchers to determine in which tissues the miRNA activity is required to restore the phenotype. The UAS-miRNA strains also can be used to overexpress or misexpress miRNAs in a wild-type genetic background, either throughout the animal or in selected locations, to uncover phenotypic effects from gain-of-function activity, lending insights into the various processes that miRNAs regulate. This approach is a particularly powerful for assigning functionality to miRNAs that do not have obvious phenotypes in loss-of-function or knockdown screens.

One research group generated strains to express 149 distinct miRNA hairpins either singly or as co-expressed clusters, and the researchers produced multiple insertion strains for each UAS-miRNA to create an allelic series.22 These strains have an added tag, either Ds-Red or luciferase, that allows one to verify the location of UAS-miRNA expression in a cell autonomous manner. UAS-Ds-Red-miRNA constructs were randomly integrated into the genome via P-element transgenesis, while the UAS-luc-miRNA constructs were non-randomly inserted at the attP2 docking site at position 68A4 on the 3rd chromosome.22 While expression of the P-element-based UAS-miRNA may be affected by insertion location, the 107 UAS-luc-miRNA insertions in the attP2 landing site are less likely to suffer from positional effects on expression. Ubiquitous overexpression of approximately two-thirds of the UAS-miRNA transgenes resulted in embryonic or larval lethality, while targeted overexpression in wing discs phenocopied effects of mutations in known wing developmental pathways, providing a starting point for investigating how specific miRNAs function in signaling pathways via their regulatory effects on mRNAs.22

A second library covers 180 evolutionarily conserved and highly expressed miRNAs.23 All of the UAS-miRNA constructs in this group were integrated at the attP landing site at position 86Fb on the 3rd chromosome to reduce positional effects on expression. Overexpression caused developmental or observable phenotypes in wings or eyes for 78/180 (43%) of the insertions.

The third set of strains allows overexpression of 89 miRNAs or clusters for a total of 109 miRNAs.24 Most UAS-miRNA constructs were inserted at defined sites, but a few (marked with Ds-Red) are from random insertions in the genome. A unique feature of this set of strains is that some of the miRNA sequences were cloned into UAST-based vectors for somatic expression, while vectors with a UASP backbone were used to allow germline overexpression of miRNAs. The strains from all 3 research groups are available at public Drosophila stock centers (Table 1).

Other in vivo tools and considerations

The strains described above provide a gateway for identifying specific biologic functions as well as the mRNA targets of Drosophila miRNAs. One particularly important feature of the GAL4/UAS system and its associated tools, such as UAS-miRNA-SP and UAS-miRNA, is that the strains contain stable transgenes that are transmitted to progeny via genetic crosses. Given the stability of in vivo expression constructs, they are not susceptible to issues with transfection efficiency or dilution over time. However, there are important experimental considerations that can enhance the utility of the knockout, over/misexpression and sponge strains in phenotypic screens. For example, individual miRNA reduction or overexpression does not always produce a phenotype. However, effects can be enhanced through use of sensitized genetic backgrounds that reduce the dosage of key genes related to a phenotype of interest.13,24 In one study, mutants with reduced minus gene expression, which decreases scutellar bristle length, were used as the genetic background for a suppressor/enhancer screen with UAS-miRNA overexpression transgenes. In several cases, the miRNA suppressors identified in the screen were predicted to regulate candidate target genes in genomic regions that were identified via a deletion-based suppressor screen.24 A similar approach can be used for other tissues and phenotypes. For UAS-miRNA-SP alleles that reduce miRNA activity rather than eliminate miRNA expression, a dicer-1 (which encodes an enzyme necessary for mature miRNA production) mutant background may provide a means for enhancing phenotypic effects.

For some phenotypes, particularly those related to behavior and physiology, the genetic background and other environmental factors can have a tremendous influence on the experimental results,25,26 and it is possible that loci with modulatory roles are more sensitive to genetic background effects. For screens focused on physiology or behavioral phenotypes, a best practice is to backcross all alleles into a common genetic background for 6–10 generations to increase the likelihood that any detected effects are a result of the miRNA manipulation rather than epistatic interactions within the genetic background. In practice, creating these strains is logistically challenging and time consuming since there are several hundred knockout, overexpression or sponge strains available for testing, and many of them will be crossed to an enhancer-Gal4 strain as well for phenotypic testing. Initially, it is more expedient to screen with the available strains “as is” using the closest available control genotypes, such as the original strains in which miRNA deletions or UAS-miRNA insertions were created. Fortunately, the miRNA strains from laboratories that have created strain libraries are often in a similar genetic background.8,21–24 For UAS-miRNA-SP alleles, comparisons also can be made to a “scrambled” control, which randomizes the sequence of the miRNA under study.21 However, “scrambled” controls are available only a small number of Drosophila miRNAs and have been produced on an as-needed basis by individual laboratories, severely limiting the current utility of this approach.

A simple option to confirm phenotypic effects of homozygous miRNA deletion alleles is to use a standard genetic non-complementation test in which a deficiency (Df) chromosome that removes the region containing the miRNA is present in trans with the miRNA-specific deletion allele. The phenotype of miRNA deletion/Df animals will be similar to that of miRNA deletion homozygotes if the miRNA is, indeed, responsible. This strategy also is useful because it removes miRNA activity while facilitating testing of miRNA mutants in a different genetic background. miRNAs that cause similar, robust phenotypes in a variety of genetic backgrounds may be the best candidates for downstream investigations. Once candidate miRNAs are identified from initial screens, the alleles can be backcrossed into a common background for further analysis or the effects can be validated using other genetic and molecular approaches.

Quantifying miRNA expression

While genetic approaches have been used widely to assess the functions of individual miRNAs,8,21,22,27 high-throughput approaches for miRNA expression profiling have received attention because of the need to clarify location, identity and levels of miRNA expression in wild-type and genetically manipulated animals. Such knowledge also is helpful for initial selection of appropriate tissue-specific enhancer-gal4 strains for UAS-miRNA or UAS-miRNA-SP experiments. The most commonly used strategies for assessing miRNA expression include quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR)-based approaches, hybridization-based techniques, and sequencing. Other high-throughput techniques, such as bead-based flow cytometry,28 are used less commonly.

qRT-PCR

qRT-PCR provides a sensitive and robust platform for miRNA quantification on a medium-throughput scale and also provides an important means for confirming results obtained from microarray or deep sequencing techniques that are described below. It can be used for the detection of both precursor and mature forms of miRNAs. One limitation of this approach is that performing several reactions in parallel can prove to be challenging since reverse transcription is performed using miRNA sequence-specific primers (instead of the conventional polyA binding primers), and the optimal conditions for the different primers can vary.29 An alternate approach is to first polyadenylate miRNAs and then use oligo-d(T)s for reverse transcription. This procedure involves the additional step of priming the polyA tail, and miRNA-specific primers are still needed for amplification of the cDNA. Because miRNA-specific primers are required, qRT-PCR cannot be used for identification and quantification of novel miRNAs. A major advantage of using this approach, however, is the high level of accuracy achieved in miRNA quantification. Additionally, qRT-PCR requires smaller starting sample amounts than other strategies.30,31

Microarray

An economical method for simultaneous profiling of numerous known miRNAs is the use of microarrays. Microarrays are fabricated with a miRNA gene-specific oligonucleotide probe library. In a commonly used strategy, biotin-labeled cDNA targets, obtained via reverse transcription of sample RNA, are then hybridized onto these chips, and Alexa-conjugated Streptavidin is subsequently used for staining followed by laser scanning of the chips. Depending on the design of the probe, microarrays can be used for the detection of both precursor and mature versions of miRNAs,32 and protocols are generally easy to optimize. While high-throughput miRNA expression profiling is an obvious advantage of microarrays, limitations of this technique include lower specificity toward highly similar targets and the fact that discovery of novel miRNAs is not possible. This method is popular for assessing genome-wide disease-specific miRNA signatures32 but is losing favor to direct sequencing strategies.

High-throughput sequencing

While miRNA quantification methods involving hybridization provide comprehensive coverage of relevant miRNAs, deep sequencing of cDNA libraries created from size-selected small RNAs provides the obvious advantage that isomiRs (variants of miRNAs) and novel miRNAs can be discovered, since the detection of miRNAs by sequencing does not rely on predetermined knowledge of miRNA sample content. IsomiR identification is aided by the single nucleotide resolution of sequencing technologies.33 Sequencing also has the advantage over computational approaches (described below) for miRNA discovery because it is not dependent on miRNA conservation.

Despite the broad applicability of high-throughput sequencing, there are technical barriers to using this approach for analyzing miRNA populations. The 2 biggest disadvantages include the quantity of starting material that is required and the biases that are introduced at various stages of sample preparation for sequencing. cDNA library preparation conventionally involves T4 RNA ligase mediated adaptor ligation to the 3′ and 5′ ends of isolated RNAs. The different enzymes used for these reactions have sequence-specific biases that can lead to under or overrepresentation of some miRNA sequences.34 After ligation the products are reverse transcribed and PCR amplified. The process requires several gel purification and steps, and the sample losses accumulate at every step. To compensate for this loss, the starting material needs to be in the pico- to microgram range, which is much higher than the required starting amount for techniques such as qRT-PCR. Moreover, the library preparation kits are costly. Several variations in protocols are being introduced to overcome the challenges associated with low quantities of some miRNAs such as single RNA-adaptor ligation or circularization of cDNA.33 Once sequencing has been performed, results are compiled in the form of FastQ files. Adaptor sequences are then removed from each read, and the remaining sequences are assigned to different libraries based on the bar codes that were introduced during library preparation. Reads are then filtered based on the length. PCR hotspot correction is often implemented on the read counts and the reads are aligned with a reference genome. Reads are also aligned to annotated sequences from miRBase and are then normalized as reads per million of aligned reads.33 One of the challenges associated with normalization of miRNA reads is that several miRNAs are expressed at much higher levels than other miRNAs. Correction methods such as the TMM normalization method are used to account for such effects.35

An important consideration for analyzing miRNA profiles is the presence of 3′ end and 5′ end modifications. Most miRNAs have variants known as isomiRs, including 5′ variants for several canonical miRNAs.36 miRNA 3′ end heterogeneity affects stability and function whereas the 5′ end alterations can affect the miRNA seed sequence important for mRNA target recognition. For many miRNAs the abundance of the star species (opposite strand, also known as the “passenger” strand) nearly equals the abundance of the “guide” strand, which is generally more abundant and produces the mature and biologically active miRNA. Therefore 5′ and 3′ heterogeneity as well as activity of the star species increases the targeting capacity of many miRNAs.

Much information about Drosophila miRNAs comes from the libraries that were generated from the modENCODE project.36 Applications of miRNA sequencing in Drosophila have involved comparison of overall small RNA expression between cell lines and tissues at different developmental stages to identify populations of small RNAs commonly expressed across different tissues and cell lines.35 This approach also gives insights into the most abundant classes of miRNAs expressed in a specific tissue type. mirBase catalogs small RNA sequencing data from NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus database.37 This public repository contains miRNA expression data from various developmental stages from both male and female Drosophila (http://www.mirbase.org/cgi-bin/experiment_summary.pl?organism = dmeandtissue = All), and knowledge of the tissue-specific expression patterns of candidates from miRNA genetic studies may provide a means to triage candidates for downstream analysis.

Web-based tools for miRNA target gene prediction and gene network analysis

Web-based approaches provide complementary strategies to the mutant, knockdown and overexpression studies described previously since miRNAs generally target multiple genes, the identities of which need to be determined as part of the functional characterization of the miRNA's contribution to an identified phenotype. There are numerous online resources available to aid researchers in predicting specific functions for a miRNA of interest in vivo. The most basic jumping off point for these studies is target prediction software, which identifies potential mRNA targets of miRNAs. Beyond predicting single target genes, it can be important to know if a specific miRNA or a group of miRNAs, particularly those producing related phenotypes in screens, regulates mRNAs associated with related gene pathways and networks. Other useful tools catalog and compare differential miRNA expression.

Target prediction and gene network analysis

Web-based tools allow one to take a particular miRNA of interest and identify potential target genes as well as possible genetic pathways in which miRNAs function. Similarly, it is possible to search for miRNAs that may regulate a specific transcript of interest. These tools use mathematical algorithms to identify 7-mer or 8-mer sites in the 3′UTRs of mRNAs that are complementary to the seed sequences (nucleotides 2–7) near the 5′ end of mature miRNAs. Of course, as with any prediction based upon sequence homology, the results are only a starting point for identifying potential miRNA/mRNA interactions and different web-based searches can yield very different results.

miRPath v.3, which is part of the DIANA Tools suite, assesses candidate pathways controlled by one or more user-submitted miRNAs in 7 species, including D. melanogaster.38 miRNA involvement in KEGG molecular pathways and gene ontology categories can be assessed. The most recent update included the importing of over 600,000 experimentally validated miRNA targets from DIANA-TarBase v7.0.39 Finally, mirExTra 2.0 is another member of the DIANA Tools suite, and allows users to examine differential expression of miRNAs and their targets.40 The user can examine changes in miRNA profiles based on variables such as sex, age, or other conditions. This tool also contains a Central microRNA Discovery (CmD) module, in which users can upload expression data to determine miRNAs controlling mRNAs or transcription factors controlling miRNAs and mRNAs.

Comparison of miRNA target prediction algorithms

Five main algorithms are used for predicting potential miRNA targets: miRanda, PicTar, TargetScan, RNA22, and PITA. In addition to these 5, miRror 2.0 is a tool that allows users to query 2 or more target prediction databases (running PicTar, PITA, miRanda, etc.) for a set of miRNAs and then returns a group of potential mRNA targets upon which the set of miRNAs may be functioning cooperatively.41 Alternatively, the user may input a set of genes to obtain a list of miRNAs that may regulate them.

To demonstrate the varying results of the 5 algorithms in broad use, we performed a search with the highly conserved miR-305, which is expressed in taxa outside of the Sophophora subgenus that contains Drosophila, using each of these algorithms. The predicted number of mRNA targets for miR-305 using the 5 software packages ranged from 68 to 1565 candidate mRNAs with as many as 17, 734 potential miR-305 target sites.

miRanda

The web-based platform available at www.microRNA.org uses the miRanda algorithm42 to search 45,671 predicted miRNA target sites that are derived from 10,532 Drosophila genes, some of which are alternative 3′UTR isoforms. A query with miR-305 identifies 1565 potential target mRNAs. Prediction with miRanda is based mostly on finding highly complementary sequences between the miRNA seed region and the mRNA. Initial matches are pared down by examining the heteroduplex free energy, and results that are evolutionarily conserved are given as final results.

PicTar

Unlike other algorithms, the PicTar algorithm does not require a perfect match when aligning the seed sequence to potential targets, but instead is more stringent when accounting for free energy with imperfect matches.43 The online tool has 2 preset options that vary the sensitivity and specificity of the alignments, with S3 being more stringent than S1. When searching for targets of mir-305 using the PicTar algorithm, S1 produces 230 potential target sites on 3′UTRs from 159 genes. The S3 option gives 100 potential 3′UTR sites from 68 gene targets.

TargetScan

The TargetScan algorithm requires an exact match of at least 7 bases within the seed sequence to get a “hit” when predicting potential targets. It allows comparisons against 14,053 unique Drosophila genes for candidate miRNA target regions in gene 3′UTRs that match miRNA seed sequences as determined by the TargetScanS algorithm.44,45 The search can be limited to targets of miRNAs that are conserved beyond the Sophophora subgenus or the algorithm can be used to search for targets of non-conserved miRNAs.

A TargetScan query yields a list of 272 candidate genes that miR-305 may regulate. These genes contain a total of 281 highly conserved sites (9 genes have 2 conserved miRNA interaction sites), and 23 of the candidate target genes have an additional non-conserved miRNA target site as well. These same candidate genes have conserved miR-305 target sequences in most of the 12 Drosophila species that have been sequenced, which strengthens the argument that they may have functional interactions with miR-305.

RNA22

Predictions given by the RNA22 algorithm rely on shared sequence patterns of miRNAs.46 Predictions are made by determining the lowest free energy associations between potential targets and known miRNAs. Differing from the other algorithms, RNA22 allows for seed mismatches and does not limit searches for target sites to 3′UTR sequences. One can use the interactive RNA22 v2.0 to upload a defined list of miRNAs and target sequences, or one can use a static, precomputed version. The static version allows the user to choose the species and the databases that the miRNAs and target mRNAs are drawn from. When querying the precomputed data for targets of mir-305–5p (the “active” miRNA sequence), 17,734 sites are found.

PITA

The PITA algorithm is unique in that it not only accounts for the free energy required to form the duplex between the miRNA and mRNA, but also for access to the target site on the mRNA so it may be bound by the miRNA.47 When this algorithm is used to predict targets of mir-305, the output is 2 separate Excel files: one for target sites on transcripts, of which there are 323, and another for the genes targeted, 311 in total.

The difference in output from these target prediction tools highlights the need to maintain a healthy dose of skepticism of the search results, the importance of comparing results from multiple strategies to identify candidate miRNA target genes, and the necessity of downstream validation techniques that provide direct assessment of interactions between miRNAs and their targets as well as demonstration of post-transcriptional silencing.

Summary

Recently, a more complete set of genetic tools for miRNA functional analysis in Drosophila has become widely available to the research community. These tools include strains such as miRNA deletions, sponges, and expression lines that allow for the phenotypic characterization of individual miRNAs. The recent development of alleles to manipulate miRNA expression takes advantage of the preexisting GAL4/UAS system and can therefore be integrated into any Drosophila genetics laboratory with ease. Other methods for discovering Drosophila miRNA function include expression analysis via microarray, qRT-PCR, or small RNA sequencing. These types of studies can provide insight into changes in miRNA profiles in response to environmental stimuli or disease, or simply provide a starting list of potential miRNA players in a given process of interest. Finally, candidate miRNA targets can be identified with the aid of any of the multiple online bioinformatics analysis packages. The potentially large lists of targets these packages generate can be pared down by using programs such as mirRor 2.0 to compare targets between multiple platforms to provide a list of fewer but more probable candidate targets.

The production of the described genetic tools has enabled researchers to begin analyzing miRNA function in Drosophila, yet the possible investigative depth is limited by the incomplete set of tools developed. As researchers continue to investigate functions of miRNAs, they should incorporate newer technologies for creating precise miRNA deletions, single nucleotide substitutions or insertions, such as reporter genes, in miRNA loci. The newest technique for generating these types of alleles is the CRISPR/CAS9 system, which allows highly efficient production of double-stranded DNA breaks that can be repaired through homologous recombination with a provided donor sequence.48,49 The relative ease of producing alleles coupled with the ability to create a wide variety of tools in the same genetic background make this newer technology appealing for targeting specific miRNAs for mutation in a common genetic background.

The strain libraries developed thus far have focused on miRNAs that are either highly conserved or expressed, meaning that tools do not exist to study miRNAs that are unique to Drosophila or are expressed at low levels. Manipulation of these non-conserved miRNAs may cause phenotypes, and further characterization of these effects could then be reapplied to miRNAs in general. In support of this assertion, several animal miRNAs are limited to specific species or evolutionary lineages yet have important modulatory functions.50–53 Exclusion of low expression miRNAs can also cause researchers to miss interesting candidates during screens, as miRNA expression levels and their likeliness to cause phenotypes are not necessarily correlated. To this end, completion of deletion, sponge, and miRNA expression libraries will further empower researchers to identify and characterize interesting miRNAs.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant IOS#1121517 to G.E.C.

References

- 1.Chalfie M, Horvitz HR, Sulston JE. Mutations that lead to reiterations in the cell lineages of C. elegans. Cell 1981; 24:59-69; PMID:7237544; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90501-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993; 75:843-54; PMID:8252621; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 1993; 75:855-62; PMID:8252622; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI, Maller B, Hayward DC, Ball EE, Degnan B, Müller P, Spring J, Srinivasan A, Fishman M, Finnerty J, Corbo J, Levine M, Leahy P, Davidson E, Ruvkun G. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature 2000; 408:86-9; PMID:11081512; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35040556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2000; 403:901-6; PMID:10706289; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35002607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha M, Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15:509-24; PMID:25027649; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm3838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hausser J, Zavolan M. 2014. Identification and consequences of miRNA-target interactions–beyond repression of gene expression. Nat Rev Genet 2014; 15:599-612; PMID:25022902; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrg3765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen YW, Song S, Weng R, Verma P, Kugler J-M, Cohen SM. Systematic study of Drosophila microRNA functions using a collection of targeted knockout mutations. Dev Cell 2014; 31:784-800; PMID:25535920; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selbach M, Schwanhäusser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nat 2008; 455:58-63; PMID:18668040; http://dx.doi.org/19167326 10.1038/nature07228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 2009; 136:215-33; PMID:19167326; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Abbott AL, Lau NC, Hellman AB, McGonagle SM, Bartel DP, Ambros VR, Horvitz HR. Most Caenorhabditis elegans microRNAs are individually not essential for development or viability. PLoS Genet 2007; 3:e215; PMID:18085825; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvarez-Saavedra E, Horvitz HR. Many families of C. elegans microRNAs are not essential for development or viability. Curr Biol 2010; 20:367-73; PMID:20096582; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenner JL, Jasiewicz KL, Fahley AF, Kemp BJ, Abbott AL. Loss of individual microRNAs causes mutant phenotypes in sensitized genetic backgrounds in C. elegans. Curr Biol 2010; 20:1321-25; PMID:20579881; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baccarini A, Chauhan H, Gardner TJ, Jayaprakash AD, Sachidanandam R, Brown BD. Kinetic analysis reveals the fate of a microRNA following target regulation in mammalian cells. Curr Biol 2011; 21:369-76; PMID:21353554; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullokandov G, Baccarini A, Ruzo A, Jayaprakash AD, Tung N, Israelow B, Evans MJ, Sachidanandam R, and Brown BD. High-throughput assessment of microRNA activity and function using microRNA sensor and decoy libraries. Nat Methods 2012; 9:840-6; PMID:22751203; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nmeth.2078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 1993; 118:401-15; PMID:8223268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGuire SE, Mao Z, Davis RL. Spatiotemporal gene expression targeting with the TARGET and gene-switch systems in Drosophila. Sci. STKE 2004; 220:pl6; PMID:15262411; http://dx.doi.org/11675496 10.1016/j.tig.2004.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roman G, Endo K, Zong L, Davis RL. P{Switch}, a system for spatial and temporal control of gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98:12602-7; PMID:11675496; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.221303998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.St. Johnston D. Using mutants, knockdowns, and transgenesis to investigate gene function in Drosophila. WIREs Dev Biol 2013; 2:587-613; PMID:24014449; http://dx.doi.org/19915559 10.1002/wdev.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loya CM, Lu CS, Van Vactor D, Fulga TA. Transgenic microRNA inhibition with spatiotemporal specificity in intact organisms. Nat Methods 2009; 6:897-903; PMID:19915559; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nmeth.1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fulga TA, McNeill EM, Binari R, Yelick J, Blanche A, Booker M, Steinkraus BR, Schnall-Levin M, Zhao Y, DeLuca T, Bejarano F, Han Z, Lai EC, Wall DP, Perrimon N, Van Vactor D. A transgenic resource for conditional competitive inhibition of conserved Drosophila microRNAs. Nat Commun 2015; 6:7279; PMID:26081261; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms8279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bejarano F, Bortolamiol-Becet D, Dai Q, Sun K, Saj A, Chou YT, Raleigh DR, Kim K, Ni JQ, Duan H, Yang JS, Fulga TA, Van Vactor D, Perrimon N, Lai EC. A genome-wide transgenic resource for conditional expression of Drosophila microRNAs. Development 2012; 139:2821-31; PMID:22745315; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.079939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schertel C, Rutishauser T, Förstemann K, Basler K. Functional characterization of Drosophila microRNAs by a novel in vivo library. Genetics 2012; 192:1543-52; PMID:23051640; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.112.145383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szuplewski S, Kugler J-M, Lim SF, Verma P, Chen Y-W, Cohen SM. MicroRNA transgene overexpression complements deficiency-based modifier screens in Drosophila. Genetics 2012; 190:617-26; PMID:22095085; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.111.136689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Dell KM. The voyeurs' guide to Drosophila melanogaster courtship. Behavioural Processes 2003; 64:211-23; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0376-6357(03)00136-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tennessen JM, Barry WE, Cox J, Thummel CS. Methods for studying metabolism in Drosophila. Methods 2014; 68:105-15; PMID:24631891; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takada S, Sato T, Ito Y, Yamashita S, Kato T, Kawasumi M, Kanai-Azuma M, Igarashi A, Kato T, Tamano M, Asahara H. Targeted gene deletion of miRNAs in mice by TALEN system. PLoS One 2013; 8:e76004; PMID:24146809; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0076004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebert BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA, Downing JR, Jacks T, Horvitz HR, Golub TR. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nat 2005; 435:834-38; PMID:15944708; http://dx.doi.org/22510765 10.1038/nature03702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pritchard CC, Cheng HH, Tewari M. MicroRNA profiling: approaches and considerations. Nat Rev Genet 2012; 13:358-69; PMID:22510765; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrg3198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer JA, Zhou Z, Lee DH, Nguyen JT, Barbisin M, Xu NL, Mahuvakar VR, Andersen MR, Lao KQ, Livak KJ and Guegler KJ. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem–loop RT–PCR. Nucl Acids Res 2005; 33:e179; PMID:16314309; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gni178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raymond CK, Roberts BS, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Johnson JM. Simple, quantitative primer-extension PCR assay for direct monitoring of microRNAs and short-interfering RNAs. RNA 2005; 11:1737-44; PMID:16244135; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.2148705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu CG, Calin GA, Volinia S, Croce CM. MicroRNA expression profiling using microarrays. Nat Protoc 2008; 3:563-78; PMID:18388938; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nprot.2008.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sterling CH, Veksler-Lublinsky I, Ambros V. An efficient and sensitive method for preparing cDNA libraries from scarce biological samples. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43:e1; PMID:25056322; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gku637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hafner M, Renwick N, Brown M, Mihailović A, Holoch D, Lin C, Pena JT, Nusbaum JD, Morozov P, Ludwig J, Ojo T, Luo S, Schroth G, Tuschl T. RNA-ligase-dependent biases in miRNA representation in deep-sequenced small RNA cDNA libraries. RNA 2011; 17:1697-1712; PMID:21775473; http://dx.doi.org/24985917 10.1261/rna.2799511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wen J, Mohammed J, Bortolamiol-Becet D, Tsai H, Robine N, Westholm JO, Ladewig E, Dai Q, Okamura K, Flynt AS, Zhang D, Andrews J, Cherbas L, Kaufman TC, Cherbas P, Siepel A, Lai EC. Diversity of miRNAs, siRNAs, and piRNAs across 25 Drosophila cell lines. Genome Res 2014; 24:1236-50; PMID:24985917; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.161554.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berezikov E, Robine N, Samsonova A, Westholm JO, Naqvi A, Hung JH, Okamura K, Dai Q, Bortolamiol-Becet D, Martin R, Zhao Y, Zamore PD, Hannon GJ, Marra MA, Weng Z, Perrimon N, Lai EC. Deep annotation of Drosophila melanogaster microRNAs yields insights into their processing, modification, and emergence. Genome Res 2011; 21:203-15; PMID:21177969; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.116657.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucl Acids Res 2008; 36:D154-58; PMID:17991681; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkm952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vlachos IS, Zagganas K, Paraskevopoulou MD, Georgakilas G, Karagkouni D, Vergoulis T, Dalamagas T, Hatzigeorgiou AG. DIANA-miRPath v3.0: deciphering microRNA function with experimental support. Nucl Acids Res 2015; 43:W460-6; PMID:25977294; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkv403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vlachos IS, Paraskevopoulou MD, Karagkouni D, Georgakilas G, Vergoulis T, Kanellos I, Anastasopoulos I.-L, Maniou S, Karathanou K, Kalfakakou D. DIANA-TarBase v7.0: indexing more than half a million experimentally supported miRNA:mRNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:D153-9; PMID:25416803; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gku1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vlachos IS, Vergoulis T, Paraskevopoulou MD, Lykokanellos F, Georgakilas G, Georgiou P, Chatzopoulos S, Karagkouni D, Christodoulou F, Dalamagas T, Hatzigeorgiou AG. DIANA-mirExTra v2.0: uncovering microRNAs and transcription factors with crucial roles in NGS expression data. Nucl Acids Res 2016; 44:W128-34; PMID:27207881; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkw455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friedman Y, Naamati G, Linial M. MiRror: a combinatorial analysis web tool for ensembles of microRNAs and their targets. Bioinformatics 2010; 26:1920-21; PMID:20529892; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Enright AJ, John B, Gaul U, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol 2003; 5:R1; PMID:14709173; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grün D, Wang YL, Langenberger D, Gunsalus KC, Rajewsky N. microRNA target predictions across 7 Drosophila species and comparison to mammalian targets. PLoS Comp Biol 2005; 1:e13; PMID:16103902; http://dx.doi.org/15652477 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 2005; 120:15-20; PMID:15652477; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruby JG, Stark A, Johnston WK, Kellis M, Bartel DP, Lai EC. Evolution, biogenesis, expression, and target predictions of a substantially expanded set of Drosophila microRNAs. Genome Res 2007; 17:1850-64; PMID:17989254; http://dx.doi.org/16990141 10.1101/gr.6597907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miranda KC, Huynh T, Tay Y, Ang YS, Tam WL, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. A pattern-based method for the identification of microRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell 2006; 126:1203-17; PMID:16990141; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kertesz M, Iovino N, Unnerstall U, Gaul U, Segal E. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nat Genet 2007; 39:1278-84; PMID:17893677; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng2135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ren X, Sun J, Housden BE, Hu Y, Roesel C, Lin S, Liu LP, Yang Z, Mao D, Sun L, Wu Q, Ji JY, Xi J, Mohr SE, Xu J, Perrimon N, Ni JQ. Optimized gene editing technology for Drosophila melanogaster using germ line-specific Cas9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:19012-7; PMID:24191015; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1318481110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Housden BE, Perrimon N. Cas9-Mediated Genome Engineering in Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2016; 2016(9):pdb.top086843; PMID:2758778621809363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang JF, He ML, Fu WM, Wang H, Chen LZ, Zhu X, Chen Y, Xie D, Lai P, Chen G, Lu G, Lin MC, Kung HF. Primate-specific microRNA-637 inhibits tumorigenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma by disrupting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling. Hepatology 2011; 54:2137-48; PMID:21809363; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/hep.24595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mor E, Cabilly Y, Goldshmit Y, Zalts H, Modai S, Edry L, Elroy-Stein O, Shomron N. Species-specific microRNA roles elucidated following astrocyte activation. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39:3710-23; PMID:21247879; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkq1325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang R, Li L, Zhu D, Hou D, Cao T, Gu H, Zhang J, Chen J, Zhang CY, Zen K. Mouse miRNA-709 directly regulates miRNA-15a/16-1 biogenesis at the posttranscriptional level in the nucleus: evidence for a microRNA hierarchy system. Cell Res 2012; 22:504-15; PMID:21862971; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cr.2011.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mor E, Shomron N. Species-specific microRNA regulation influences phenotypic variability: perspectives on species-specific microRNA regulation. Bioessays. 2013; 35:881-8; PMID:23864354; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bies.201200157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]