ABSTRACT

RUNX1 plays opposing roles in breast cancer: a tumor suppressor in estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) disease and an oncogenic role in ER-negative (ER−) tumors. Potentially mediating the former, we have recently reported that RUNX1 prevents estrogen-driven suppression of the mRNA encoding the tumor suppressor AXIN1. Accordingly, AXIN1 protein expression was diminished upon RUNX1 silencing in ER+ breast cancer cells and was positively correlated with AXIN1 protein expression across tumors with high levels of ER. Here we report the surprising observation that RUNX1 and AXIN1 proteins are strongly correlated in ER− tumors as well. However, this correlation is not attributable to regulation of AXIN1 by RUNX1 or vice versa. The unexpected correlation between RUNX1, playing an oncogenic role in ER− breast cancer, and AXIN1, a well-established tumor suppressor hub, may be related to a high ratio between the expression of variant 2 and variant 1 (v2/v1) of AXIN1 in ER− compared with ER+ breast cancer. Although both isoforms are similarly regulated by RUNX1 in estrogen-stimulated ER+ breast cancer cells, the higher v2/v1 ratio in ER− disease is expected to weaken the tumor suppressor activity of AXIN1 in these tumors.

KEYWORDS: AXIN1 alternative splicing, oncogene, tumor suppressor

Introduction

In addition to their developmental roles, the 3 transcription factors in the mammalian RUNX family play context-specific roles in cancer as either tumor suppressors or oncogenes.1-6 RUNX1 is a master regulator of haematopoietic cell fate determination and is frequently disrupted in leukemias.7-11 Recently, its role in estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer suppression has been disclosed based on identification of recurrent somatic mutations and/or deletions in tumor biopsies.12-14 Even though Runx1 knockout is insufficient for breast cancer initiation,15 its silencing in ER+ breast cancer cells in vitro has been shown to increase cell proliferation and expression of stem cell markers, attributable to decreased expression of the tumor suppressor AXIN1.1

AXIN1 is a multidomain scaffold protein with a tumor suppressor activity mostly attributable to its role as a rate-limiting factor in the ß-catenin destruction complex.16-18 Besides its well-known function as a negative regulator of Wnt/ß-catenin signaling,17-19 AXIN1 has been implicated in coordinating several other pathways including TGFβ, SAPK/JNK, p53, YAP/TAZ and Myc.20-24 Two major isoforms of AXIN1 have been described, with variant 1(v1) comprising 11 exons and v2 lacking exon 9, which encodes a PP2A binding domain that likely plays a role in destabilizing Myc by dephosphorylation of S6222. Although AXIN1 is a well-recognized tumor suppressor with multiple mutations identified in several different cancers,25-28 no recurrent mutations in AXIN1 have been identified in breast cancer.14 In our recent study, however, we demonstrated that RUNX1 and estrogens combinatorially regulated the AXIN1 gene in breast cancer cells, so that AXIN1 expression was downregulated when RUNX1 was lost while ER was active.1 Additionally, breast carcinogenesis is accompanied with an increase in the v2/v1 ratio between the 2 AXIN1 isoforms.29

Despite significant improvements to early detection and the development of effective hormonal and other therapies, breast cancer is predicted to claim more than 40,000 female lives in the United States in 201630. Heterogeneity of breast cancer is critical in disease management. More than 2 thirds of all tumors are ER+ and/or PR+/HER2−, 12% are triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), 10% are ER+ and/or PR+/HER2+, and 5% are ER−/HER2+ 31. HER2+ and TNBC patients have poor survival compared with ER+ breast cancer patients. Whereas ER+ and HER2+ patients can benefit from hormonal (Tamoxifen, Fulvestrant, Letrozole)32-36 and anti-HER2 therapies (Trastuzumab, Lapatinib),37,38 no targeted therapeutic approaches are available for aggressive TNBC.39-42

An increasing body of evidence points at context-dependent functional interaction between sex hormone steroid signaling and the roles that RUNX proteins play in cancer.43-48 In breast cancer, interactions of RUNX proteins with estrogen signaling are critical for their roles as either tumor suppressors or oncogenes.1,6,49,50 Recurrent inactivating mutations in RUNX1 are specific to ER+ tumors.14,15 Rather than functioning as a tumor suppressor, RUNX1 expression in TNBC correlates with poor prognosis and its silencing in a cell culture model of TNBC ameliorates cancer-related phenotypes.51-53 In this study we report the unexpected positive association between RUNX1 and AXIN1 in ER− breast cancer and present evidence suggesting that the association of RUNX1 with tumor aggression in this breast cancer subtype can be explained in part by the preferential expression of AXIN1v2.

Materials and methods

Cells

The ER+ MCF7 and the ER− MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in DMEM (Mediatech, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gemini Bio-products) and in DMEM/F12 (Mediatech, Inc.) supplemented with 5% FBS, respectively. Construction of the MCF7/shRx1dox cells and MDA-MB-231/shRx1dox cells, conditionally expressing shRNAs for RUNX1 upon doxycycline (dox) treatment, has been described previously.1 For hormone depletion, cells were washed 3 times with PBS and maintained for 48 h in phenol-red free growth medium supplemented with 10% charcoal stripped serum (CSS) (Gemini Bio-products) before treatment.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using Aurum™ Total RNA mini-kit (BioRad) and cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA with qScript™ cDNA SuperMix (Quanta Biosciences). Quantitative Real Time PCR was performed in triplicate using Maxima SYBR Green/Fluorescein Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific) with CFX96 instrument (BioRad). Relative mRNA expression values were normalized to 18S RNA. Primers used for RT-qPCR were 5′ -CAAGCAGAGGTATGTGCAGGA- 3′ (Forward) and 5′ -CACAACGATGCTGTCACACG- 3′ (Reverse) for Axin1 v1; and 5′ -AAGCAGAGGACAAGATCGCA- 3′ (Forward) and 5′ -CGCAGAAGTAGTACGCCACA- 3′ (Reverse) for Axin1 v2.

Tissue microarray analysis

Breast cancer tissue microarray (TMA) slides used in this study were purchased from Protein Biotechnologies, Inc. (TM-1007). Represented in this TMA are 34 ER− tumors, including 33 cases of invasive ductal carcinoma and 1 case of ductal carcinoma in situ. TMA slides were immunostained as described previously using antibodies against RUNX1 (#8529) or AXIN1 (#2087) from Cell Signaling Technology.1 ER and Ki67 histoscores were provided by the manufacturer and presence or absence of RUNX1 and AXIN1 was determined by a certified surgical pathologist at USC. Association between the RUNX1 and AXIN1 status was tested using the Pearson chi-square test for the 2 × 2 table using MedCalc (http://medcalc.com).

Data mining

RNA-sequencing data for the breast cancer cohort of TCGA was downloaded from the TCGA Data Portal (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). Isoform sequencing data and exon sequencing data for AXIN1 was analyzed using Partek Genomics Suite 6.4 (Partek, Inc.).

Results

Correlation between RUNX1 and AXIN1 in ER− breast cancer tumors

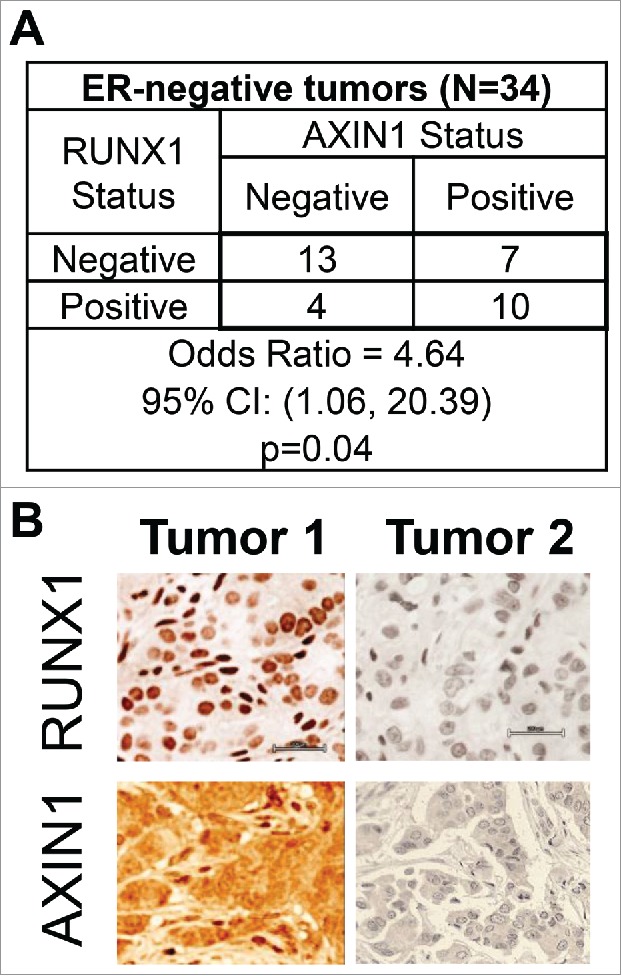

Based on clinical data mining of RUNX1-depleted ER+ breast cancer cells and genome-wide analyses of ER+ breast epithelial cells in vivo and in vitro, we have recently demonstrated that RUNX1 antagonized estrogen-mediated AXIN1 suppression.1 Consistent with this model, immunohistochemical analysis of 31 ER+ breast cancer tumors in a tissue microarray (TMA-1007 from Protein Biotechnologies) indicated positive correlation between RUNX1 and AXIN1 in a manner dependent on ERα expression.1 Analysis of 34 ER− tumors that were represented in the same TMA revealed that RUNX1 and AXIN1 were strongly correlated in the ER− tumors as well (Fig. 1). This observation was unexpected because unlike ER+ breast cancer cells, RUNX1 manipulation in ER− breast cancer cells did not affect AXIN1 expression.1 Additionally, unlike in ER+ tumors, RUNX1 does not appear to play a tumor suppressor role in ER− breast cancer. Not only is the RUNX1 locus devoid of recurrent mutation,14 RUNX1 expression in ER− breast cancer actually correlates with disease aggression.51-53

Figure 1.

Association between RUNX1 and AXIN1 in ER− breast cancer tumors. Breast cancer tumor microarray TMA-1007 from Protein Biotechnologies, Inc. was immunostained for RUNX1 and AXIN1. The ER− invasive ductal carcinomas were designated as positive or negative for RUNX1 and AXIN1. (A) RUNX1 and AXIN1 status, and the odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for the association between AXIN1 status and RUNX1 status in the ER− tumors in the TMA. Association between the RUNX1 status and AXIN1 status was tested using the Pearson chi-square test for the 2 × 2 table. (B) RUNX1 and AXIN1 immunohistochemical staining of 2 representative ER− tumors from the TMA illustrating the association between RUNX1 and AXIN1 expression.

Alternative splicing of AXIN1 in ER− vs. ER+ breast cancer

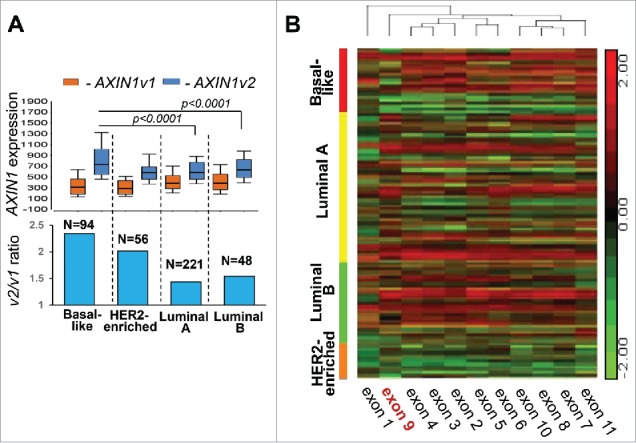

RUNX1 appears to play opposite roles in ER+ and ER− breast cancer, yet the tumor suppressor AXIN1 is positively correlated with RUNX1 in both ER+ and ER− tumors (Fig. 1 and ref. 1). To resolve this conundrum, we hypothesized that ER− tumors express at relatively higher level of the cancer-associated variant 2 of AXIN1 (AXIN1v2). We tested this hypothesis by interrogating the breast cancer RNA-seq database of TCGA. Indeed, although v2 is the transcript expressed at higher levels across all tumor subtypes, its levels are highest in the basal-like subtype and the v2/v1 ratio is higher in ER− (Basal-like and HER2-enriched) compared with ER+ (Luminal A and Luminal B) tumors (Fig. 2A). Accordingly, a heat map describing expression of each AXIN1 exon across the breast cancer tumors in TCGA demonstrates reduced expression of AXIN1 exon 9 in ER- tumors, in particular the basal-like subtype (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

AXIN1 splice variant expression in breast cancer subtypes. (A) Box-whisker plot describing the differential expression of AXIN1 variants (upper panel) and their ratio (lower panel) in breast cancer subtypes. (B) Semi-supervised hierarchical clustering for expression of AXIN1 exons in breast cancer subtypes. Expression of AXIN1 variants was represented by RSEM normalized values of the individual isoforms and expression of AXIN1 exons was represented by RPKM values in the Level-3 RNA-seqV2 data downloaded from the TCGA data portal. P-values were calculated by ANOVA.

Positive correlation of each of RUNX1 and AXIN1 with the Ki67 index in ER− breast cancer

We next calculated the correlation between each of RUNX1 and AXIN1 across the 34 ER− breast cancer tumors in the TMA-1007 tissue microarray with the Ki67 index provided by the manufacturer. Consistent with the proposed oncogenic role of RUNX1 in ER− breast carcinogenesis,51-53 its expression was positively correlated with the Ki67 index (p = 0.01; Table 1). Less expectedly, AXIN1 expression was also positively correlated with the Ki67 index (Table 1). This finding suggests that AXIN1 plays a weak, if any, tumor suppressor role in ER− breast cancer, possibly related to the predominance of AXIN1v2 in these tumors.

Table 1.

Association between RUNX1 or AXIN1 and Ki67.

| ER-negative tumors (N = 34) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ki-67 status |

||

| RUNX1 Status | Negative / Mild | Positive / Strong |

| Negative | 13 | 6 |

| Positive | 3 | 11 |

| Odds Ratio = 7.94 | ||

| 95% CI: (1.69, 39.42) | ||

| p = 0.01 | ||

| (N = 34) | ||

| Ki-67 status |

||

| AXIN1 Status |

Negative / Mild |

Positive / Strong |

| Negative | 11 | 5 |

| Positive | 5 | 13 |

| Odds Ratio = 5.7 | ||

| 95% CI: (1.3, 25.05) | ||

| p = 0.02 | ||

Association between AXIN1 and RUNX1 in ER− breast cancer does not involve transcriptional control

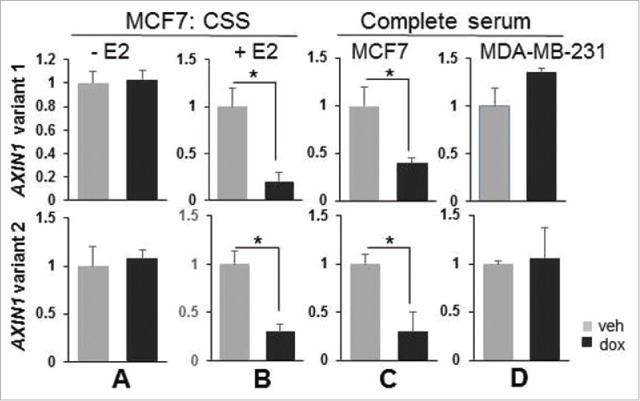

The correlation between RUNX1 and AXIN1 across ER+ breast cancer is attributable to RUNX1-mediated antagonism of AXIN1 transcriptional repression by estrogens.1 The positive correlation between RUNX1 and AXIN1 in the ER− tumors (Fig. 1) is misaligned with our observations that RUNX1 silencing did not decrease AXIN1 expression in estrogen-deprived ER+ MCF7 cells (CSS without E2 supplementation) or in ER− MBA-MB-231 cells.1 We suspected that this misalignment was attributable to differential regulation of the 2 AXIN1 variants. However, RT-qPCR analysis revealed similar regulation of AXIN1v1 and AXIN1v2. They were both downregulated by RUNX1 silencing in MCF7 cultures in the presence of estrogens (Fig. 3B-C) and they were both unaffected by RUNX1 silencing in hormone depleted MCF7 cultures (Fig. 3A) and in the ER− MDA-MB-231 cell cultures (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that the positive correlation between RUNX1 and AXIN1 in ER− breast cancer (Fig. 1) is not attributable to a RUNX1-mediated control of AXIN1 transcription.

Figure 3.

RUNX1 regulates both AXIN1v1 and AXIN1v2 in an estrogen-dependent manner. MCF7/shRx1dox (A-C) and MDA-MB-231/shRx1dox cells (D) were maintained in either 10% charcoal-stripped serum (A-B) or complete (estrogen-containing) 10% serum (C-D), and treated with dox to silence RUNX1 (A-D) and E2 (only B) for 48 h. Expression of AXIN1 transcripts v1 and v2 was measured by RT-qPCR and corrected for 18S RNA levels (Mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments). *p < 0.05 by t-test.

Discussion

RUNX proteins are known to exert context-dependent opposing roles in breast cancer. Potentially reflecting subtype-specific features, RUNX1 somatic mutations occur recurrently in ER+ but not in ER− breast cancer.14 The tumor suppressor role of RUNX1 in ER+ tumors12-14 is in part is attributable to antagonism of estrogen-mediated AXIN1 suppression.1 In ER− tumors, on the other hand, RUNX1 predominantly plays an oncogenic role, reflected in positive correlation with disease aggression and mortality52,53 as well as cancer-related phenotypes in vitro.51,52 Apparently inconsistent with the oncogenic role of RUNX1 in ER− breast cancer, its expression in these tumors is positively correlated with AXIN1 (Fig. 1). Our findings suggest that RUNX1-positive ER− tumors remain aggressive despite AXIN1 expression because they express the AXIN1 variants differently than ER+ tumors. Specifically, the ER− tumors express AXIN1 with a higher ratio between variant 2 and variant 1 (Fig. 2A).

The mechanism underlying the positive correlation between RUNX1 and AXIN1 in ER− breast cancer remains to be elucidated. Unlike in ER+ breast cancer cells, RUNX1 does not regulate AXIN1 mRNA in ER− breast cancer cells (Fig. 3). Additionally preliminary studies demonstrated indifference of RUNX1 expression to IWR1-mediated upregulation of AXIN1 (data not shown) suggesting that AXIN1 does not regulate RUNX1 expression. We cannot rule out regulation of AXIN1 by RUNX1 in vivo through a mechanism not supported in our culture models (Fig. 3). It is also possible that RUNX1 and AXIN1 are both regulated, independently, by a common upstream pathway.

Even though RUNX1 does not regulate AXIN1 in ER− breast cancer cells (Fig. 3), and even though its correlation with AXIN1 expression (Fig. 1) is easier to interpret given the ratio between the AXIN1 isoforms (Fig. 2), the molecular mechanisms underlying the oncogenic role of RUNX1 (Table 1 and refs.51-53) are poorly understood. To fulfill its oncogenic role, RUNX1 might employ mechanisms similar to those employed by RUNX2 in promoting cancer aggression.2,4,5,43,54-62 Indeed, about 2 thirds of the RUNX1 transcriptome is shared with the RUNX2 transcriptome in estrogen-deprived MCF7 cells.1 Conceivably, these shared genes contribute to aggressive disease and high mortality of patients with ER− /RUNX1+ tumors. The present study contends that high AXIN1 expression in these tumors does not provide sufficient tumor suppression because of the differential enrichment for variant 2 of AXIN1.

Disclosure of potential conflict interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Paulette Mhawech-Fauceglia for help with the scoring of the TMA and Meng Li of the USC Bioinformatics Service Program at the Norris Medical Library for helpful discussions.

Funding

We acknowledge NIH grants RO1 DK07112 and RO1 DK07112S from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) to BF, who holds the J. Harold and Edna L. LaBriola Chair in Genetic Orthopedic Research at USC. This work was also supported by an award from the SC CTSI Pilot Funding Program to NC.

References

- [1].Chimge NO, Little GH, Baniwal SK, Adisetiyo H, Xie Y, Zhang T, O'Laughlin A, Liu ZY, Ulrich P, Martin A, et al.. RUNX1 prevents oestrogen-mediated AXIN1 suppression and beta-catenin activation in ER-positive breast cancer. Nat Commun 2016; 7:10751; PMID:26916619; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms10751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pratap J, Lian JB, Stein GS. Metastatic bone disease: role of transcription factors and future targets. Bone 2011; 48:30-6 ; DOI 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cameron ER, Blyth K, Hanlon L, Kilbey A, Mackay N, Stewart M, Terry A, Vaillant F, Wotton S, Neil JC. The Runx genes as dominant oncogenes. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2003; 30:194-200; PMID:12732183; 10.1016/S1079-9796(03)00031-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ito Y, Bae SC, Chuang LS. The RUNX family: developmental regulators in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2015; 15:81-95; PMID:25592647; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc3877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Blyth K, Cameron ER, Neil JC. The RUNX genes: gain or loss of function in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2005; 5:376-87; PMID:15864279; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chimge NO, Frenkel B. The RUNX family in breast cancer: relationships with estrogen signaling. Oncogene 2013; 32:2121-30; PMID:23045283; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2012.328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ding Y, Harada Y, Imagawa J, Kimura A, Harada H. AML1/RUNX1 point mutation possibly promotes leukemic transformation in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2009; 114:5201-5; PMID:19850737; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2009-06-223982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Blyth K, Slater N, Hanlon L, Bell M, Mackay N, Stewart M, Neil JC, Cameron ER. Runx1 promotes B-cell survival and lymphoma development. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2009; 43:12-9; PMID:19269865; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bcmd.2009.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tang JL, Hou HA, Chen CY, Liu CY, Chou WC, Tseng MH, Huang CF, Lee FY, Liu MC, Yao M, et al.. AML1/RUNX1 mutations in 470 adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic implication and interaction with other gene alterations. Blood 2009; 114:5352-61; PMID:19808697; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2009-05-223784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mangan JK, Speck NA. RUNX1 Mutations in Clonal Myeloid Disorders: From Conventional Cytogenetics to Next Generation Sequencing, A Story 40 Years in the Making. Crit Rev Oncog 2011; 16:77-91; PMID:22150309; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1615/CritRevOncog.v16.i1-2.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Silva FP, Morolli B, Storlazzi CT, Anelli L, Wessels H, Bezrookove V, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Giphart-Gassler M. Identification of RUNX1/AML1 as a classical tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene 2003; 22:538-47; PMID:12555067; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1206141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Banerji S, Cibulskis K, Rangel-Escareno C, Brown KK, Carter SL, Frederick AM, Lawrence MS, Sivachenko AY, Sougnez C, Zou L, et al.. Sequence analysis of mutations and translocations across breast cancer subtypes. Nature 2012; 486:405-9; PMID:22722202; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature11154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ellis MJ, Ding L, Shen D, Luo J, Suman VJ, Wallis JW, Van Tine BA, Hoog J, Goiffon RJ, Goldstein TC, et al.. Whole-genome analysis informs breast cancer response to aromatase inhibition. Nature 2012; 486:353-60; PMID:22722193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].TCGA . Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2012; 490:61-70; PMID:23000897; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature11412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].van Bragt MP, Hu X, Xie Y, Li Z. RUNX1, a transcription factor mutated in breast cancer, controls the fate of ER-positive mammary luminal cells. Elife 2014; 4:e03881; PMID:25415051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee E, Salic A, Kruger R, Heinrich R, Kirschner MW. The roles of APC and Axin derived from experimental and theoretical analysis of the Wnt pathway. PLoS Biol 2003; 1:E10; PMID:14551908; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Li VS, Ng SS, Boersema PJ, Low TY, Karthaus WR, Gerlach JP, Mohammed S, Heck AJ, Maurice MM, Mahmoudi T, et al.. Wnt signaling through inhibition of beta-catenin degradation in an intact Axin1 complex. Cell 2012; 149:1245-56; PMID:22682247; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stamos JL, Weis WI. The beta-catenin destruction complex. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013; 5:a007898; PMID:23169527; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a007898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 2006; 127:469-80; PMID:17081971; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rui Y, Xu Z, Lin S, Li Q, Rui H, Luo W, Zhou HM, Cheung PY, Wu Z, Ye Z, et al.. Axin stimulates p53 functions by activation of HIPK2 kinase through multimeric complex formation. EMBO J 2004; 23:4583-94; PMID:15526030; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu W, Rui H, Wang J, Lin S, He Y, Chen M, Li Q, Ye Z, Zhang S, Chan SC, et al.. Axin is a scaffold protein in TGF-beta signaling that promotes degradation of Smad7 by Arkadia. EMBO J 2006; 25:1646-58; PMID:16601693; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Arnold HK, Zhang X, Daniel CJ, Tibbitts D, Escamilla-Powers J, Farrell A, Tokarz S, Morgan C, Sears RC. The Axin1 scaffold protein promotes formation of a degradation complex for c-Myc. The EMBO journal 2009; 28:500-12; PMID:19131971; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2008.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhang Y, Neo SY, Wang X, Han J, Lin SC. Axin forms a complex with MEKK1 and activates c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase through domains distinct from Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem 1999; 274:35247-54; PMID:10575011; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Azzolin L, Panciera T, Soligo S, Enzo E, Bicciato S, Dupont S, Bresolin S, Frasson C, Basso G, Guzzardo V, et al.. YAP/TAZ incorporation in the beta-catenin destruction complex orchestrates the Wnt response. Cell 2014; 158:157-70; PMID:24976009; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mazzoni SM, Fearon ER. AXIN1 and AXIN2 variants in gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer Lett 2014; 355:1-8; PMID:25236910; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Salahshor S, Woodgett JR. The links between axin and carcinogenesis. J Clin Pathol 2005; 58:225-36; PMID:15735151; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/jcp.2003.009506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Satoh S, Daigo Y, Furukawa Y, Kato T, Miwa N, Nishiwaki T, Kawasoe T, Ishiguro H, Fujita M, Tokino T, et al.. AXIN1 mutations in hepatocellular carcinomas, and growth suppression in cancer cells by virus-mediated transfer of AXIN1. Nat Genet 2000; 24:245-50; PMID:10700176; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/73448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Takai A, Dang HT, Wang XW. Identification of drivers from cancer genome diversity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2014; 15:11142-60; PMID:24955791; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms150611142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhang X, Farrell AS, Daniel CJ, Arnold H, Scanlan C, Laraway BJ, Janghorban M, Lum L, Chen D, Troxell M, et al.. Mechanistic insight into Myc stabilization in breast cancer involving aberrant Axin1 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:2790-5; PMID:21808024; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1100764108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. American Cancer Society, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Li CI, Chen VW, Clarke CA, Ries LA, Cronin KA. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106; PMID:24777111; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jnci/dju055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, Buzdar A, Howell A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11:1135-41; PMID:21087898; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70257-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ignatiadis M, Sotiriou C. Luminal breast cancer: from biology to treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013; 10:494-506; PMID:23881035; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Burstein HJ, Temin S, Anderson H, Buchholz TA, Davidson NE, Gelmon KE, Giordano SH, Hudis CA, Rowden D, Solky AJ, et al.. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32:2255-69; PMID:24868023; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Croxtall JD, McKeage K. Fulvestrant: a review of its use in the management of hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Drugs 2011; 71:363-80; PMID:21319872; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2165/11204810-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mouridsen H, Giobbie-Hurder A, Goldhirsch A, Thurlimann B, Paridaens R, Smith I, Mauriac L, Forbes J, Price KN, Regan MM, et al.. Letrozole therapy alone or in sequence with tamoxifen in women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:766-76; PMID:19692688; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa0810818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hudis CA. Trastuzumab–mechanism of action and use in clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:39-51; PMID:17611206; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMra043186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Higa GM, Abraham J. Lapatinib in the treatment of breast cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2007; 7:1183-92; PMID:17892419; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1586/14737140.7.9.1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kumar P, Aggarwal R. An overview of triple-negative breast cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2016; 293:247-69; PMID:26341644; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00404-015-3859-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Palma G, Frasci G, Chirico A, Esposito E, Siani C, Saturnino C, Arra C, Ciliberto G, Giordano A, D'Aiuto M. Triple negative breast cancer: looking for the missing link between biology and treatments. Oncotarget 2015; 6:26560-74; PMID:26387133; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.18632/oncotarget.5306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kalimutho M, Parsons K, Mittal D, Lopez JA, Srihari S, Khanna KK. Targeted Therapies for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Combating a Stubborn Disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015; 36:822-46; PMID:26538316; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tips.2015.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].den Hollander P, Savage MI, Brown PH. Targeted therapy for breast cancer prevention. Front Oncol 2013; 3:250; PMID:24069582; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fonc.2013.00250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Little GH, Baniwal SK, Adisetiyo H, Groshen S, Chimge NO, Kim SY, Khalid O, Hawes D, Jones JO, Pinski J, et al.. Differential Effects of RUNX2 on the Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer: Synergistic Stimulation of a Gene Set Exemplified by SNAI2 and Subsequent Invasiveness. Cancer Res 2014; 74:2857-68; PMID:24648349; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Baniwal SK, Khalid O, Sir D, Buchanan G, Coetzee GA, Frenkel B. Repression of Runx2 by androgen receptor (AR) in osteoblasts and prostate cancer cells: AR binds Runx2 and abrogates its recruitment to DNA. Mol Endocrinol 2009; 23:1203-14; PMID:19389811; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/me.2008-0470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Khalid O, Baniwal SK, Purcell DJ, Leclerc N, Gabet Y, Stallcup MR, Coetzee GA, Frenkel B. Modulation of Runx2 activity by estrogen receptor-alpha: implications for osteoporosis and breast cancer. Endocrinology 2008; 149:5984-95; PMID:18755791; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/en.2008-0680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kawate H, Wu Y, Ohnaka K, Takayanagi R. Mutual transactivational repression of Runx2 and the androgen receptor by an impairment of their normal compartmentalization. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2007; 105:46-56; PMID:17627815; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Takayama K, Suzuki T, Tsutsumi S, Fujimura T, Urano T, Takahashi S, Homma Y, Aburatani H, Inoue S. RUNX1, an androgen- and EZH2-regulated gene, has differential roles in AR-dependent and -independent prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2015; 6:2263-76; PMID:25537508; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.18632/oncotarget.2949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Huang B, Qu Z, Ong CW, Tsang YH, Xiao G, Shapiro D, Salto-Tellez M, Ito K, Ito Y, Chen LF. RUNX3 acts as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer by targeting estrogen receptor alpha. Oncogene 2012; 31:527-34; PMID:21706051; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2011.252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Chimge NO, Baniwal SK, Luo J, Coetzee S, Khalid O, Berman BP, Tripathy D, Ellis MJ, Frenkel B. Opposing effects of Runx2 and estradiol on breast cancer cell proliferation: in vitro identification of reciprocally regulated gene signature related to clinical letrozole responsiveness. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18:901-11; PMID:22147940; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chimge NO, Baniwal SK, Little GH, Chen YB, Kahn M, Tripathy D, Borok Z, Frenkel B. Regulation of breast cancer metastasis by Runx2 and estrogen signaling: the role of SNAI2. Breast Cancer Res 2011; 13:R127; PMID:22151997; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/bcr3073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Browne G, Dragon JA, Hong D, Messier TL, Gordon JA, Farina NH, Boyd JR, VanOudenhove JJ, Perez AW, Zaidi SK, et al.. MicroRNA-378-mediated suppression of Runx1 alleviates the aggressive phenotype of triple-negative MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Tumour Biol 2016; PMID:26749280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Browne G, Taipaleenmaki H, Bishop NM, Madasu SC, Shaw LM, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB. Runx1 is associated with breast cancer progression in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice and its depletion in vitro inhibits migration and invasion. J Cell Physiol 2015; 230:2522-32; PMID:25802202; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcp.24989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ferrari N, Mohammed ZM, Nixon C, Mason SM, Mallon E, McMillan DC, Morris JS, Cameron ER, Edwards J, Blyth K. Expression of RUNX1 correlates with poor patient prognosis in triple negative breast cancer. PLoS One 2014; 9:e100759; PMID:24967588; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0100759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Akech J, Wixted JJ, Bedard K, van der Deen M, Hussain S, Guise TA, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Languino LR, Altieri DC, et al.. Runx2 association with progression of prostate cancer in patients: mechanisms mediating bone osteolysis and osteoblastic metastatic lesions. Oncogene 2010; 29:811-21; PMID:19915614; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2009.389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Blyth K, Vaillant F, Jenkins A, McDonald L, Pringle MA, Huser C, Stein T, Neil J, Cameron ER. Runx2 in normal tissues and cancer cells: A developing story. Blood cells, molecules & diseases 2010; 45:117-23; PMID:20580290; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bcmd.2010.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Baniwal SK, Khalid O, Gabet Y, Shah RR, Purcell DJ, Mav D, Kohn-Gabet AE, Shi Y, Coetzee GA, Frenkel B. Runx2 transcriptome of prostate cancer cells: insights into invasiveness and bone metastasis. Mol Cancer 2010; 9:258; PMID:20863401; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1476-4598-9-258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Boregowda RK, Medina DJ, Markert E, Bryan MA, Chen W, Chen S, Rabkin A, Vido MJ, Gunderson SI, Chekmareva M, et al.. The transcription factor RUNX2 regulates receptor tyrosine kinase expression in melanoma. Oncotarget 2016; PMID:27102439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Guo ZJ, Yang L, Qian F, Wang YX, Yu X, Ji CD, Cui W, Xiang DF, Zhang X, Zhang P, et al.. Transcription factor RUNX2 up-regulates chemokine receptor CXCR4 to promote invasive and metastatic potentials of human gastric cancer. Oncotarget 2016; 7:20999-1012; PMID:27007162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Li XQ, Lu JT, Tan CC, Wang QS, Feng YM. RUNX2 promotes breast cancer bone metastasis by increasing integrin alpha5-mediated colonization. Cancer Lett 2016; 380:78-86; PMID:27317874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Shin MH, He Y, Marrogi E, Piperdi S, Ren L, Khanna C, Gorlick R, Liu C, Huang J. A RUNX2-Mediated Epigenetic Regulation of the Survival of p53 Defective Cancer Cells. PLoS Genet 2016; 12:e1005884; PMID:26925584; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Tandon M, Chen Z, Othman AH, Pratap J. Role of Runx2 in IGF-1Rbeta/Akt- and AMPK/Erk-dependent growth, survival and sensitivity towards metformin in breast cancer bone metastasis. Oncogene 2016; PMID:26804175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wysokinski D, Blasiak J, Pawlowska E. Role of RUNX2 in Breast Carcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2015; 16:20969-93; PMID:26404249; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms160920969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]