ABSTRACT

Macroautophagy/autophagy is a conserved catabolic process through which cellular excessive or dysfunctional proteins and organelles are transported to the lysosome for terminal degradation and recycling. Over the past few years increasing evidence has suggested that autophagy is not only a simple metabolite recycling mechanism, but also plays a critical role in the removal of intracellular pathogens such as bacteria and viruses. When autophagy engulfs intracellular pathogens, the pathway is called ‘xenophagy’ because it leads to the elimination of foreign microbes. Recent studies support the idea that xenophagy can be modulated by bacterial infection. Meanwhile, convincing evidence indicates that xenophagy may be involved in malignant transformation and cancer therapy. Xenophagy can suppress tumorigenesis, particularly during the early stages of tumor initiation. However, in established tumors, xenophagy may also function as a prosurvival pathway in response to microenvironment stresses including bacterial infection. Therefore, bacterial infection-related xenophagy may have an effect on tumor initiation and cancer treatment. However, the role and machinery of bacterial infection-related xenophagy in cancer remain elusive. Here we will discuss recent developments in our understanding of xenophagic mechanisms targeting bacteria, and how they contribute to tumor initiation and anticancer therapy. A better understanding of the role of xenophagy in bacterial infection and cancer will hopefully provide insight into the design of novel and effective therapies for cancer prevention and treatment.

KEYWORDS: bacterial, cancer therapy, carcinogenesis, infection, xenophagy

Introduction

Autophagy is a highly conserved catabolic process by which cytosolic components or organelles are sequestered within highly specialized double-membrane-bound vesicles termed autophagosomes and subsequently delivered to lysosomes for degradation.1,2 At present, 3 primary types of autophagy in eukaryotic cells have been characterized, named as selective and nonselective macroautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy.3 In this review, we will focus on the macroautophagy, hereafter referred to as autophagy. There has been an increasing interest in selective autophagy, which specifically targets particular substrates for cellular events. When autophagy engulfs foreign pathogens such as bacteria and viruses, the pathway is called ‘xenophagy’. Therefore, xenophagy provides a host defense mechanism to target and deliver these pathogens to lysosomes for degradation.4,5

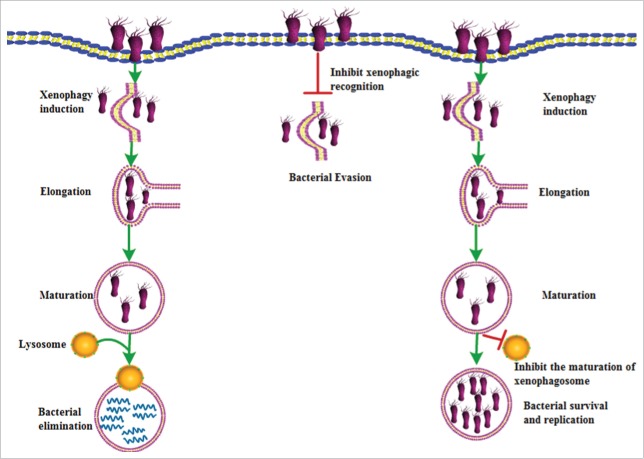

Xenophagy is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism, which is based on the specific recognition of intracellular pathogens for degradation.6 Besides its direct role in the elimination of intracellular pathogens (Fig. 1), xenophagy may also function as a host defense mechanism by enhancing innate immune responses, which are mediated by a set of genome-encoded pattern recognition molecules such as toll-like receptors, nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptors, RIG-I-like receptors and type I IFN (interferon).7,8 Meanwhile, some bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Anaplasma phagocytophilum, can utilize the autophagy machinery to survive and replicate (Fig. 1).9,10 Moreover, the outcomes of xenophagy are also determined by the extent of bacterial infection. In some cases, acute infection induces xenophagy to promote bacterial clearance.11 However, during prolonged infection bacteria may take advantage of xenophagy to support bacterial survival, resulting in chronic or recurrent infection.12 Thus, the function of xenophagy is highly dependent on the type of bacterial pathogens and treatment characteristic.

Figure 1.

Schematic for the role of xenophagy in bacterial infections. Xenophagy plays a crucial role in the elimination of intracellular bacteria. In this process, intracellular bacteria are recognized and targeted to the phagophore, then subsequently delivered to the lysosome for selective degradation. In contrast, certain bacteria have developed ways to escape the recognition to avoid elimination by xenophagy. Some bacteria may block autophagosomal maturation and acidification to generate a replicative niche in which they can survive and replicate actively.

Recently, there has been a growing interest in the relationship between bacterial infection-related xenophagy and carcinogenesis. Accumulating evidence suggests that bacterial infection can promote inflammation-mediated carcinogenesis by modulating xenophagy.13-15 Therefore, antimicrobial agents as xenophagy modulators may have new potential application for cancer. This review will summarize our current understanding of how bacterial infection manipulates the xenophagy pathway of the host and its possible role in cancer.

Bacterial elimination by xenophagic process and its molecular mechanism

Xenophagy plays a crucial role in the elimination of intracellular pathogens.16 In this process, intracellular bacteria or viruses are recognized and targeted to the phagophore, the precursor to the autophagosome, then delivered to the lysosome for selective degradation. Rikihisa, et al. was the first to report that bacteria could be eliminated by autophagy.17 Since then, a large number of studies investigated the relationship between the selective elimination of intracellular bacteria and xenophagy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Xenophagy and its role in response to different bacterial types.

| Bacterium |

Targets |

The effect of xenophagy |

Refs |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial recognition and elimination by inducing xenophagy | |||||

| GAS | SLO | Entrap GAS in xenophagic compartments | 18 | ||

| 8-nitro-cGMP | promote xenophagic exclusion of invading GAS | 20 | |||

| RAB9A, RAB23, RAB17 | Enlarge GCAVs and eventual lysosomal fusion | 22,23 | |||

| CD46 | Target GAS to xenophagic degradation | 24 | |||

| NLRP4 | Negatively regulate the xenophagic bactericidal process of GAS | 25 | |||

| S. typhimurium | SCV | Xenophagy recognizes them within damaged SCVs | 29 | ||

| SQSTM1 | Link the bacteria to phagophores via LC3 | 30 | |||

| OPTN | Promote xenophagic clearance of cytosolic Salmonella | 31 | |||

| LGALS8 | Activate xenophagy to protect the cytoplasm against bacterial infection | 32,33 | |||

| Mtb | LC3 | Induce xenophagy and eliminate bacteria | 39 | ||

| ESAT-6, TBK1, TMEM173, SQSTM1, CALCOCO2, LC3 | Promote the ubiquitin-mediated xenophagy pathway | 40 | |||

| UBQLN1 | Promote xenophagic process against these bacteria | 42,43 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ANXA2 | Induce xenophagy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection | 44 | ||

| Bacteria evading targeting by xenophagy | |||||

| S. flexneri | IcsA, IcsB | Inhibit binding of an autophagy protein to the Shigella surface protein or phagosome membrane | 45,46 | ||

| TECPR1 | Colocalize with ATG5 at Shigella-containing phagophores | 47 | |||

| L. monocytogenes | ActA | Disguise the bacteria to escape autophagic recognition and prevent ubiquitination and the recruitment of xenophagy receptors to L. monocytogenes | 49,50 | ||

| L. pneumophila | RavZ | Cleave LC3 proteins attached to phosphatidylethanolamine on phagophore membranes and inactivate the LC3 protein | 53 | ||

| LpSpl | Disruption of host sphingolipid biosynthesis | 55 | |||

| Bacteria exploiting autophagy components for replication | |||||

| S. aureus | LC3 | Xenophagy can provide a protective niche for intracellular S. aureus to survive and replicate | 9 | ||

| cAMP | Induce a xenophagic response to promote bacterial survival | 56 | |||

| Coxiella burnetii | LC3, RAB24 | Xenophagy can provide a niche more favorable to their initial survival and multiplication | 58 | ||

| H. pylori | VacA, CagA | Xenophagic vesicles serve as ecological niches for H. pylori to replicate inside the host cell | 63 | ||

| UPEC | Unknown | Hijack the autophagic pathway for prolonged intracellular survival within QIRs | 65 | ||

| Anaplasma | ATS-1 | Bind BECN1 to hijack the BECN1-ATG14 autophagy initiation pathway | 67,68 | ||

Group A Streptococcus

Xenophagic control of intracellular bacteria was initially shown in the case of Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as GAS (Group A Streptococcus).18 In HeLa cells infected with GAS, about 80% of intracellular GAS are eventually trapped by autophagosome-like compartments and eliminated upon fusion of these compartments with lysosomes. However, in autophagy-deficient ATG5−/− cells, GAS survive and replicate. Thus, the xenophagic machinery can act as an innate defense system against GAS invasion.

Mechanistically, streptolysin O, a member of the cholesterol-dependent pore-forming cytolysins, was demonstrated to be a major mediator by which GAS escapes from the endosome and then enters into the cytosol to induce xenophagy.18,19 In addition to streptolysin O, some other molecules and autophagy receptors are involved in GAS-induced xenophagy. Endogenous 8-nitroguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate, a downstream mediator of nitric oxide, promotes xenophagic exclusion of invading GAS from cells.20 Several RAB GTPases are also associated with the pathway of autophagosome formation and the fate of intracellular GAS. RAB5 was involved in bacterial invasion and endosome fusion.21 RAB7 has multifunctional roles in bacterial invasion, endosome maturation and autophagosome formation.21 RAB9A is required for the enlargement of GAS-containing autophagosome-like vacuoles and eventual lysosomal fusion.22 RAB23 is recruited to GAS-capturing forming autophagosomes.22 Moreover, not only RAB9A but also RAB23 are dispensable for starvation-induced autophagosome formation, indicating that they play a unique role in xenophagy. RAB17-mediated recycling endosomes contribute to autophagosome formation in response to GAS invasion.23 Recently, innate immune mechanisms were shown to play a role in GAS-induced activation of xenophagy. The pathogen receptor CD46 can control early bacterial infection by xenophagy and participate in the targeting of GAS to xenophagic degradation through the CD46-CYT-1 domain-GOPC-BECN1-PIK3C3/VPS34 pathway.24 NLRP4, a member of nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptor family, has a strong affinity for BECN1. NLRP4 suppression via RNA interference results in upregulation of the autophagic process in response to invasive bacterial infections, leading to enhancement of the xenophagic bactericidal process against GAS.25

Salmonella typhimurium

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. typhimurium) is one well-studied example of a bacterium that is eliminated by the xenophagic pathway. S. typhimurium actively invades host cells and typically resides within a vacuolar compartment termed the Salmonella-containing vacuole (SCV). In this phagosome-like compartment, S. typhimurium can manipulate the fate of the SCV through its type III secretion system (T3SS, encoded in Salmonella pathogenicity islands 1 and 2).26,27 However, a small population of this bacterium forms a pore in the SCV through its T3SS to escape into the cytosol, where it obtains nutrients for rapid growth.28 In contrast, when S. typhimurium are exposed to the cytosol within damaged SCVs early after infection, they are recognized and targeted by xenophagy, resulting in protection of the cytosol from bacterial colonization.29

The mechanisms of selective recognition of S. typhimurium by xenophagy are still being elucidated. Among them, ubiquitinated proteins are important mediators. Upon entry into the cytosol, the bacteria are coated by a layer of polyubiquitinated proteins. These ubiquitin-positive bacteria can be detected by the receptor protein SQSTM1/p62 linking the bacteria to phagophores via LC3, resulting in infection control.30 The receptor protein OPTN also has an important role in bacterial xenophagy. The protein kinase TBK1 (TANK binding kinase 1) can phosphorylate OPTN on serine 177, which promotes LC3 binding affinity and xenophagic clearance of cytosolic Salmonella.31 In addition, sugar signals such as β-galactoside are also involved in bacterial infection-induced xenophagy. β-galactoside may be recognized by its cytosolic ligand LGALS8 (galectin 8). By recruiting CALCOCO2/NDP52 (calcium binding and coiled-coil domain 2) to the bacterial ubiquitin coat as well as LC3, LGALS8 activates xenophagy to protect the cytoplasm against bacterial infection.32,33 Taken together, these ubiquitin or sugar signals contribute to the xenophagy of bacteria in damaged vacuoles.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is another bacterium that is targeted for xenophagy in damaged vacuoles. One of the main features of Mtb is its potential to infect and survive in alveolar macrophages. During infection of macrophages, Mtb resides within a phagosome and blocks phagosome maturation.34 However, phagosome maturation in infected macrophages can be restored through exogenous induction of xenophagy via several immunological and pharmacological autophagy inducers, such as IFNG/IFN-γ, vitamin D, ATP-P2RX7/P2×7 and toll-like receptor ligands.35-38 As a consequence, Mtb can be eliminated by stimulating the xenophagic pathway.

An early study showed that Mtb-containing phagosomes can interact with the autophagy effector LC3, which is necessary for inducing xenophagy and eliminating intracellular mycobacteria.39 The results from Watson, et al. indicate that ESAT-6/EsxA (early secreted antigenic target of 6 kDa), which is the major substrate secreted from the bacterial type VII secretion system ESX-1, is a major factor for the ubiquitin-mediated xenophagy pathway targeting phagosomal Mtb.40 The same research showed that recognition of extracelluar bacterial DNA through TBK1 and the TMEM173/STING pathway is required for ubiquitin-mediated selective autophagy of Mtb. Delivery of bacilli to phagophores requires the ubiquitin-autophagy receptors SQSTM1, CALCOCO2 and LC3 to access the mycobacteria-containing phagosome. Mtb infection of Atg5 conditional knockout mice results in increased bacillary burden and excessive pulmonary inflammation.41 RAB7 and UBQLN1 (ubiquilin 1) were also recently implicated in promoting the xenophagic process in response to these bacteria.42,43

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an environmentally ubiquitous gram negative bacterial pathogen and may induce xenophagy in mast cells, which have been recognized as sentinels in the host defense against bacterial infection.11 However, the mechanism underlying selective induction of xenophagy in response to bacterial invasion is not fully elucidated. ANXA2 (annexin A2) induces xenophagy through inhibiting the AKT1-MTOR-ULK1/2 signaling pathway, which plays a crucial role in host defense against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection (i.e., AKT1-MTOR inhibit ULK1/2-dependent autophagy).44

The molecular mechanism of xenophagic evasion by bacteria

Although xenophagy is a powerful defense mechanism as described above, certain pathogens have developed ways to escape this defense system to avoid complete destruction by xenophagy. A very interesting xenophagic escape mechanism has been unveiled in the case of Shigella flexneri, Listeria monocytogenes and Legionella pneumophila (Table 1).

Shigella flexneri is a gram-negative pathogen that has the ability to evade the xenophagic pathway. S. flexneri can escape from phagosomes into the cytoplasm by secreting factor IcsB and IcsA/VirG via the T3SS system.45 IcsB contributes to S. flexneri evasion of xenophagy by inhibiting binding of the autophagy protein ATG5 to the Shigella surface protein IcsA or suppressing LC3-associated phagocytosis and LC3 recruitment to vacuolar membrane remnants.45,46 TECPR1 (tectonin β-propeller repeat containing 1) is another effector that colocalizes with ATG5 at Shigella-containing phagophores. Therefore, TECPR1 activity is necessary for efficient xenophagic targeting of bacteria, and a deficiency of TECPR1 supports increased intracellular multiplication of Shigella.47

Listeria monocytogenes is another pathogen that can evade recognition by the xenophagic machinery. L. monocytogenes infection can induce the activation of xenophagy in macrophages. During the initial phase of infection by Listeria (approximately 1 h post-infection), ∼37% of intracellular bacteria colocalize with the autophagy marker LC3, being targeted by xenophagy in a listeriolysin O-dependent manner.48 At later stages of infection (approximately 4 h post-infection), the majority of L. monocytogenes escapes xenophagic recognition and rapidly replicates, which is attributed to the expression of ActA; this protein can disguise the bacteria from xenophagic recognition by directly recruiting the ARP2/3 complex and and ENAH-VASP to the bacterial surface.49 Meanwhile, ActA also prevents ubiquitination and the recruitment of autophagy receptors (SQSTM1, LC3 and CALCOCO2) to L. monocytogenes.49,50 Taken together, these mechanisms allow bacteria to escape the recognition by the xenophagic pathway.

Legionella pneumophila is a facultative intracellular pathogen of free-living amoebae and mammalian phagocytes. L. pneumophila can employ a type IV secretion system (T4SS, also known as the secretion system Dot/Icm) to enter a lipid-raft-rich spacious vacuole that is quickly enveloped by the endoplasmic reticulum, then avoids fusion with lysosomes.51,52 Infection with L. pneumophila results in the decreased expression of a large number of xenophagy genes such as ATG3, ATG7 and LC3. Among these genes, LC3 plays an important role in L. pneumophila infection. L. pneumophila can escape xenophagy by using its effector protein RavZ to directly cleave LC3 proteins attached to phosphatidylethanolamine on phagophore membranes resulting in permanent inactivation of the LC3 protein.53 RavZ targets LC3 via the phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate-binding module and a C-terminal domain motif.54 Another L. pneumophila effector protein, LpSpl (sphingosine-1 phosphate lyase), also inhibits autophagosome formation during macrophage infection, which seemed to be associated with the disruption of host sphingolipid biosynthesis.55

The molecular mechanism of bacterial replication through exploitation of xenophagy

In contrast to the bacteria that try to avoid autophagic elimination, certain bacteria actively exploit xenophagy for intracellular growth; thus, defective replication is found in autophagy-deficient cells (Table 1).

A well-studied example of a bacterium that utilizes xenophagic components to support its replication is Staphylococcus aureus. After invasion of HeLa cells, S. aureus transits to phagophores through colocalization with LC3, ending up within autophagosomes, which provides a protective niche for intracellular S. aureus to survive and replicate.9 Additionally, S. aureus can induce a xenophagic response in infected cells by decreasing intracellular cAMP levels, which is beneficial for bacterial survival.56

Coxiella burnetii is another example of a bacterium that hijacks xenophagy. C. burnetii survives in a Coxiella-containing vacuole after invasion of host cells.57 After 24–48 h post infection, C. burnetii phase II replicative vacuoles are generated and are decorated with LC3 and RAB24, which provides a niche more favorable to their initial survival and multiplication.58 C. burnetii infection also recruits BECN1 and BCL2 to the Coxiella-containing vacuole, and the interaction between these 2 proteins is important for bacterial replication and inhibition of apoptosis.59 Overall, xenophagy induction favors the intracellular differentiation and survival of the bacteria.

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative pathogen that can invade both gastric epithelial cells and professional phagocytes.60 Recent studies have suggested that H. pylori can induce xenophagy via VacA (vacuolating cytotoxin A) and CagA (cytotoxin-associated gene A).61,62 Currently, it is increasingly acknowledged that H. pylori-induced xenophagy provides the bacterium a protective mechanism whereby xenophagic vesicles serve as ecological niches for H. pylori to replicate inside the host cell.63

UPEC (uropathogenic Escherichia coli) is a primary pathogen involved in UTI (urinary tract infection). UPEC forms acute cytoplasmic biofilms termed intracellular bacterial communities within superficial urothelial cells and can persist by establishing membrane-enclosed latent reservoirs termed quiescent intracellular reservoirs (QIRs) to seed recurrent UTI.64,65 UPEC can hijack the xenophagic pathway for prolonged intracellular survival within QIRs.65 ATG16L1 plays an important role in UTI pathogenesis, and ATG16L1 deficiency contributes to protecting the host against both acute and latent UPEC infection.66

Anaplasma phagocytophilum is a gram-negative intracellular bacterium that replicates in a membrane-bound compartment resembling an early autophagosome. Niu and colleagues found that Ats-1 (Anaplasma translocated substrate 1), a type IV secretion effector, can bind BECN1 to hijack the BECN1-ATG14 autophagy initiation pathway to acquire host nutrients for intracellular bacterial growth.67,68 This finding unraveled a mechanism by which bacteria obtain nutrients from host cells through Ats-1-induced xenophagy to promote intracellular replication.

The role of xenophagy in bacterial-associated cancer

Autophagy, a crucial mechanism for the maintenance of intracellular homeostasis, is now emerging as an important player in tumor initiation and cancer development. In healthy cells, autophagy functions as a homeostatic machinery to protect cells against malignant transformation.69 Moreover, autophagy is also required for efficient anticancer immunosurveillance.70 In cancer cells, however, autophagy can constitute a prosurvival mechanism to cope with intracellular and environmental stresses, thus favoring tumor progression, at least in some settings.71 Owing to its different role in the elimination or preservation of intracellular bacteria strains, xenophagy displays different effects on cancer (Table 2).

Table 2.

The role of xenophagy in response to different bacterial strains in cancer.

| Bacterium | Targets | Type of cancer | The effect on xenophagy and cancer | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. pylori | CagA, CD44 | Gastric cancer | Inhibit xenophagy and promote carcinogenesis | 15 |

| PgdA | Gastric cancer | Inhibit xenophagy and promote carcinogenesis | 74 | |

| ATG16L1 rs2241880 | Gastric cancer | Inhibit xenophagy and promote carcinogenesis | 75 | |

| S. typhimurium | AKT-MTOR-RPS6KB | Melanoma | Induce xenophagy to promote cancer cell death | 76 |

| ATG5, BECN1 | Liver cancer | Induce xenophagy as a protective role for infected cancer cells | 77 |

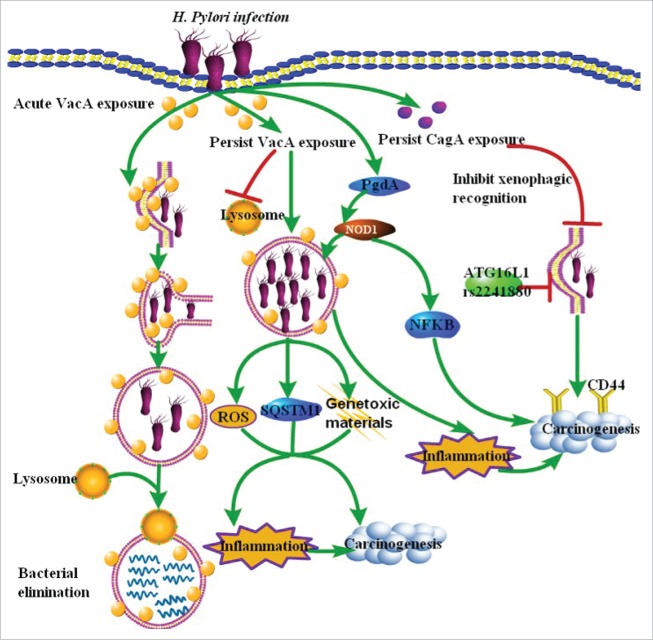

H. pylori infection is the strongest known risk factor for gastric carcinogenesis. Many effects of H. pylori on gastric epithelial cells are attributed to the 2 secreted bacterial proteins VacA and CagA (Fig. 2). One effect of acute VacA exposure is the induction of xenophagy to protect against infection with H. pylori. However, prolonged exposure to the toxin strongly disrupts xenophagy and promotes infection, which can contribute to inflammation and eventual carcinogenesis through increasing the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), SQSTM1 and genotoxic materials in epithelial cells.72,73 Sustained expression of CagA is also closely associated with the formation of gastric cancer. CagA is normally degraded by ROS-induced xenophagy in infected cells. However, xenophagy is compromised in infected CD44-expressing gastric cancer stem-like cells. As a result, CagA can specifically accumulate in the host cytoplasm, leading to carcinogenesis.15 Moreover, wild-type CagA transgenic mice display severe gastric epithelial hyperplasia and some of the mice develop gastric polyps and gastric adenocarcinoma by gain-of-function PTPN11/SHP-2 mutations.13 In addition to VacA and CagA, PgdA (peptidoglycan deacetylase) plays a crucial role in modulating host inflammatory responses to H. pylori, allowing the bacteria to persist and eventually induce gastric cancer by decreasing NOD1-dependent NFKB activation and xenophagy (Fig. 2).74 Moreover, xenophagy appears to be a pivotal mechanism involved in H. pylori recognition and H. pylori-related gastric cancer. The highly virulent H. pylori strain GC026 that is associated with gastric cancer can markedly downregulate xenophagy in AGS cells. Individuals carrying the ATG16L1 rs2241880 variant have an increased risk of H. pylori infection and gastric cancer, indicating that a xenophagy defect may be associated with the initiation of gastric cancer.75 Therefore, infection with H. pylori may serve as a model system to investigate the role of xenophagy disruption in microbial-mediated carcinogenesis.

Figure 2.

Model summarizing current understanding of H. pylori-related xenophagy and gastric cancer initiation. H. pylori can induce xenophagy in gastric epithelial cells via VacA and CagA. Acute VacA exposure can induce xenophagy to protect against infection with H. pylori. However, prolonged or persist exposure to the toxin strongly disrupts xenophagy and promotes infection, which contributes to inflammation and eventual carcinogenesis through increasing the accumulation of ROS, SQSTM1 and genotoxic materials in epithelial cells. Similarly, accumulated CagA may specifically accumulate in gastric cells expressing the cancer stem cell marker CD44 by escaping from xenophagy. Besides VacA and CagA, PgdA allows the bacteria to persist and eventually induce gastric cancer by decreaseing NOD1-dependent NFKB activation and xenophagy. The ATG16L1 rs2241880 variant also increases the risk of H. pylori infection and gastric cancer.

S. typhimurium induces xenophagic activation in melanoma cells via downregulation of the AKT-MTOR-RPS6KB/p70S6K pathway.76 When Salmonella accumulates in tumor sites, cancer cells try to induce a strong xenophagic response to eliminate the bacteria, resulting in the inhibition of tumor growth, which is associated with the induction and processing of the autophagy marker LC3.76 Another study from Liu, et al. showed that tumor-targeting Salmonella A1-R or Salmonella strain VNP20009 induce xenophagy in human liver cancer cells, which serves a protective role for infected cancer cells. Knockdown of essential autophagy genes ATG5 or BECN1 in bacteria-infected cancer cells leads to a significant increase of intracellular bacteria multiplication in cancer cells and further retards cancer cell growth.77 Thus, the combination therapy of xenophagy blockage with infection by tumor-targeting Salmonella may be a novel approach to enhance cancer-cell killing.

The emerging potential in cancer prevention and treatment with antimicrobial drugs based on xenophagy modulation

As mentioned above, bacterial clearance after infection may be modulated by xenophagy. Meanwhile, bacterial infection is thought to be a major risk factor for tumor initiation and cancer development.78,79 For example, H. pylori infection can promote gastric tumor formation in mice and humans by methylation of trefoil factors.79 Chronic colitis can alter the microbiome to promote the initiation of colitis-associated cancer by altering microbial composition and inducing the expansion of microorganisms with genotoxic capabilities.80,81 Since bacteria-associated xenophagy can regulate the microbiome and altered microbial flora may promote inflammation-mediated tumorigenesis, antimicrobial drugs may have the potential of cancer prevention by regulating the xenophagic pathway (Table 3). However, there are limited studies to investigate the relationship between antimicrobial drugs and xenophagy in carcinogenesis. Nitazoxanide, a well known antimicrobial drug, has been recently discovered to have potential anticancer properties. Nitazoxanide might simultaneously offer anti-inflammatory and pro-autophagic actions in mouse models with bacterial lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages through blocking the production of IL6, which constitutes a barrier against various inflammatory processes including malignant transformation.82,83 The role of other antimicrobial drugs in xenophagy and bacterial-associated cancer needs to be further investigated.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial drugs and their effect on xenophagy in cancer.

| Bacterium | Targets | Type of cancer | The effect on xenophagy and cancer | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTZ | IL6 | Unknown | Induce xenophagy to promote cancer cell death | 82,83 |

| CAM | Unknown | MALT | Induce cancer cell death | 84,85 |

| TKs | calcium-BAK1 | HCC | Induce xenophagy to promote cancer cell death | 87 |

| VIO | LC3 | Head and neck cancer | Induce xenophagy to promote cancer cell death | 88 |

| BCG | ATG2B | Bladder cancer | Induce xenophagy to promote cancer cell death | 89 |

| Salinomycin | ROS | Osteosarcoma | Induce xenophagy to promote cancer cell survival | 90 |

Note. CAM, clarithromycin; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; NTZ, nitazoxanide; TKs, trichokonins; VIO, violacein.

In addition to cancer prevention, there is increasing interest in the potential of antimicrobial drugs as new anti-cancer agents. Clarithromycin is a well-known macrolide antibiotic which is used to protect the host against various bacterial infections including H. pylori. Development and growth of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas are often associated with H. pylori infection. Extensive preclinical and clinical data support that clarithromycin as a single agent or in combination with conventional strategies has the potential against some H. pylori-associated cancers such as MALT.84,85 However, it still needs to be further investigated whether or not xenophagy is involved in this process. The antibiotic drug tigecycline can induce xenophagy but not apoptosis to inhibit gastric cancer cell proliferation, suggesting tigecycline might act as a candidate agent for pre-clinical evaluation in treatment of gastric cancer patients.86 Trichokonins, the peptaibols (biologically active peptides) secreted by T. koningii, have antibacterial and antifungal properties. A recent study showed that trichokonin V exhibits its cytotoxic effects on hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inducing calcium-calpain-BAX-mediated apoptosis and calcium-BAK1-mediated xenophagy.87 Violacein (VIO), produced by a limited number of Gram negative bacteria species, has anticancer activity. VIO treatment enhances the expression of LC3-II and cell death in head and neck cancer cells, indicating VIO may be useful in the inhibition of cancer cell growth through inducing xenophagy.88 In addition to its effects against tuberculosis, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination also induces nonspecific beneficial effects on immune cells to increase their ability against infections and malignancies. Pharmacological inhibition of xenophagy as well as ATG2B polymorphism blocks BCG-induced trained immunity; thus, promoting xenophagy will hopefully provide new possibilities for improvement of BCG-based vaccines to be used against infections and malignancies in the future.89 Although antimicrobial drugs can exhibit their anticancer potential by inducing pro-death xenophagy, there is a conflicting report regarding the potential role of xenophagy. Salinomycin, a polyether antibiotic, can promote apoptosis and xenophagy through generation of ROS in osteosarcoma U2OS cells.90 Furthermore, the inhibition of xenophagy by 3-methyladenine enhances salinoymcin-induced apoptosis, suggesting salinomycin induces xenophagy as a survival mechanism to favor cancer cell survival.90 Therefore, antimicrobial drugs may induce different effects of xenophagy on cell survival in different cancer types.

Conclusions and perspectives

Autophagy as an important membrane transport pathway is involved in several physiological and pathological processes. Antibacterial autophagy, also referred to as xenophagy, triggers selective recognition of intracellular bacteria and redirects them to the xenophagic machinery for degradation. In some cases, xenophagy displays a direct role in the elimination of intracellular bacteria; however, several bacteria may also utilize, and even actively manipulate, the xenophagy machinery to survive and replicate. Currently, the mechanism underlying selective activation of xenophagy in response to bacterial infection is largely unknown.

Persistent bacterial infection can induce chronic mucosal inflammation which is a significant risk factor for the formation and development of many cancer types, such as gastric cancer, colitis-associated cancer and MALT.91,92 Therefore, the eradication of intracellular pathogenic bacteria may offer the greatest clinical benefit to cancer patients with this type of infection. Since xenophagy has a direct role in pathogen clearance, manipulating the xenophagic pathway may have an effect on tumor initiation and cancer development through regulating the microbiome and altering microbial flora. Based on the specific recognition of intracellular bacteria for degradation via xenophagy, some antimicrobial drugs have been developed as new anticancer agents. Currently, preclinical and clinical studies have identified the possible anticancer application of antimicrobial drugs in combination with conventional strategies or even as a single agent.

Although antimicrobial therapy based on modulation of xenophagy is attracting more and more attention in cancer prevention and treatment, several fundamental questions about xenophagy-associated antimicrobial therapy and the fate of intracellular bacteria remain to be answered. First, as with autophagy, the question of whether we should try to trigger or suppress xenophagy in bacteria-associated cancer is not straightforward since it might vary according to the type of bacterial strains and the extent of bacterial infection. Inhibition of xenophagy can enhance infection by some bacterial pathogens, whereas induction of xenophagy can enhance infection by others.93 Therefore, it requires us not only to be highly cautious in the application of xenophagic modulators to treat infection-associated cancer but also to monitor the infectious risk during the use of such modulators. Second, although preclinical and clinical studies have confirmed the anticancer potential of antimicrobial drugs, evidence regarding the antitumor activity of these agents is still scarce. Large-scale and multicenter clinical trials will be needed. Third, how to detect the xenophagic responses in clinical samples is an issue. New and reliable methods for measuring xenophagy need to be developed in the future. The fourth critical challenge is determining possible mechanisms by which antimicrobial drugs induce xenophagy and the pharmacokinetics of antimicrobial drugs in combination with other regimens. It is therefore imperative to better understand how to manipulate xenophagy modulated by intracellular bacteria, and how this influences cancer initiation and tumor development.

Abbreviations

- CagA

cytotoxin-associated gene A

- CALCOCO2/NDP52

calcium binding and coiled-coil domain 2

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GAS

Group A Streptococcus

- MALT

mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- QIRs

quiescent intracellular reservoirs

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SCV

Salmonella-containing vacuole

- T3SS

type III secretion system

- TBK1

TANK binding kinase 1

- TEPCR1

tectonin β-propeller repeat containing 1

- UBQLN1

ubiquilin 1

- UPEC

uropathogenic Escherichia coli

- UTI

urinary tract infection

- VacA

vacuolating cytotoxin A

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed. None of the contents of this manuscript has been previously published or is under consideration elsewhere. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript prior to submission.

Funding

This study is supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 81301891 and 81672932), Zhejiang province science and technology project of TCM (grant No. 2015ZB033) and Zhengshu Medical Elite Scholarship Fund.

References

- [1].Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 2008; 451:1069-75; PMID: 18305538; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Klionsky DJ, Abdelmohsen K, Abe A, Abedin MJ, Abeliovich H, Acevedo Arozena A, Adachi H, Adams CM, Adams PD, Adeli K, et al.. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy 2016; 12:1-222; PMID: 26799652; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12:814-22; PMID: 20811353; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb0910-814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Samson E. Xenophagy. Br Dent J 1981; 150:136; PMID: 6937205; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bdj.4804559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bauckman KA, Owusu-Boaitey N, Mysorekar IU. Selective autophagy: xenophagy. Methods 2015; 75:120-7; PMID: 25497060; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gomes LC, Dikic I. Autophagy in antimicrobial immunity. Mol Cell 2014; 54:224-33; PMID: 24766886; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yano T, Kurata S. Intracellular recognition of pathogens and autophagy as an innate immune host defence. J Biochem 2011; 150:143-9; PMID: 21729928; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1093/jb/mvr083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Desai M, Fang R, Sun J. The role of autophagy in microbial infection and immunity. Immunotargets Ther 2015; 4:13-26; PMID: 27471708; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.2147/ITT.S76720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Schnaith A, Kashkar H, Leggio SA, Addicks K, Kronke M, Krut O. Staphylococcus aureus subvert autophagy for induction of caspase-independent host cell death. J Biol Chem 2007; 282:2695-706; PMID: 17135247; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M609784200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Niu H, Yamaguchi M, Rikihisa Y. Subversion of cellular autophagy by Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Cell Microbiol 2008; 10:593-605; PMID: 17979984; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01068.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Junkins RD, Shen A, Rosen K, McCormick C, Lin TJ. Autophagy enhances bacterial clearance during P. aeruginosa lung infection. PloS One 2013; 8:e72263; PMID: 24015228; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0072263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bauckman KA, Mysorekar IU. Ferritinophagy drives uropathogenic Escherichia coli persistence in bladder epithelial cells. Autophagy 2016; 12:850-63; PMID: 27002654; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1080/15548627.2016.1160176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ohnishi N, Yuasa H, Tanaka S, Sawa H, Miura M, Matsui A, Higashi H, Musashi M, Iwabuchi K, Suzuki M, et al.. Transgenic expression of Helicobacter pylori CagA induces gastrointestinal and hematopoietic neoplasms in mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:1003-8; PMID: 18192401; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0711183105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Levy J, Cacheux W, Bara MA, L'Hermitte A, Lepage P, Fraudeau M, Trentesaux C, Lemarchand J, Durand A, Crain AM, et al.. Intestinal inhibition of Atg7 prevents tumour initiation through a microbiome-influenced immune response and suppresses tumour growth. Nat Cell Biol 2015; 17:1062-73; PMID: 26214133; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb3206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tsugawa H, Suzuki H, Saya H, Hatakeyama M, Hirayama T, Hirata K, Nagano O, Matsuzaki J, Hibi T. Reactive oxygen species-induced autophagic degradation of Helicobacter pylori CagA is specifically suppressed in cancer stem-like cells. Cell Host Microbe 2012; 12:764-77; PMID: 23245321; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chom.2012.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Alexander DE, Leib DA. Xenophagy in herpes simplex virus replication and pathogenesis. Autophagy 2008; 4:101-3; PMID: 18000391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rikihisa Y. Glycogen autophagosomes in polymorphonuclear leukocytes induced by rickettsiae. Anatomical Record 1984; 208:319-27; PMID: 6721227; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1002/ar.1092080302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nakagawa I, Amano A, Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Yamaguchi H, Kamimoto T, Nara A, Funao J, Nakata M, Tsuda K, et al.. Autophagy defends cells against invading group A Streptococcus. Science 2004; 306:1037-40; PMID: 15528445; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1103966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].O'Neill AM, Thurston TL, Holden DW. Cytosolic replication of Group A streptococcus in human macrophages. MBio 2016; 7:e00020-16; PMID: 27073088; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1128/mBio.00020-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ito C, Saito Y, Nozawa T, Fujii S, Sawa T, Inoue H, Matsunaga T, Khan S, Akashi S, Hashimoto R, et al.. Endogenous nitrated nucleotide is a key mediator of autophagy and innate defense against bacteria. Mol Cell 2013; 52:794-804; PMID: 24268578; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sakurai A, Maruyama F, Funao J, Nozawa T, Aikawa C, Okahashi N, Shintani S, Hamada S, Ooshima T, Nakagawa I. Specific behavior of intracellular Streptococcus pyogenes that has undergone autophagic degradation is associated with bacterial streptolysin O and host small G proteins Rab5 and Rab7. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:22666-75; PMID: 20472552; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M109.100131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Nozawa T, Aikawa C, Goda A, Maruyama F, Hamada S, Nakagawa I. The small GTPases Rab9A and Rab23 function at distinct steps in autophagy during Group A Streptococcus infection. Cell Microbiol 2012; 14:1149-65; PMID: 22452336; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01792.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Haobam B, Nozawa T, Minowa-Nozawa A, Tanaka M, Oda S, Watanabe T, Azocar O, Vidalain PO, Vidal M, Lotteau V, et al.. Rab17-mediated recycling endosomes contribute to autophagosome formation in response to Group A Streptococcus invasion. Cell Microbiol 2014; 16:1806-21; PMID: 25052408; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1111/cmi.12329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Joubert PE, Meiffren G, Gregoire IP, Pontini G, Richetta C, Flacher M, Azocar O, Vidalain PO, Vidal M, Lotteau V, et al.. Autophagy induction by the pathogen receptor CD46. Cell Host Microbe 2009; 6:354-66; PMID: 19837375; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chom.2009.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jounai N, Kobiyama K, Shiina M, Ogata K, Ishii KJ, Takeshita F. NLRP4 negatively regulates autophagic processes through an association with beclin1. J Immunol 2011; 186:1646-55; PMID: 21209283; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1001654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Brumell JH, Grinstein S. Salmonella redirects phagosomal maturation. Curr Opin Microbiol 2004; 7:78-84; PMID: 15036145; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mib.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Knodler LA, Steele-Mortimer O. Taking possession: biogenesis of the Salmonella-containing vacuole. Traffic 2003; 4:587-99; PMID: 12911813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Birmingham CL, Smith AC, Bakowski MA, Yoshimori T, Brumell JH. Autophagy controls Salmonella infection in response to damage to the Salmonella-containing vacuole. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:11374-83; PMID: 16495224; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M509157200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Birmingham CL, Brumell JH. Autophagy recognizes intracellular Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in damaged vacuoles. Autophagy 2006; 2:156-8; PMID: 16874057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zheng YT, Shahnazari S, Brech A, Lamark T, Johansen T, Brumell JH. The adaptor protein p62/SQSTM1 targets invading bacteria to the autophagy pathway. J Immunol 2009; 183:5909-16; PMID: 19812211; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.0900441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wild P, Farhan H, McEwan DG, Wagner S, Rogov VV, Brady NR, Richter B, Korac J, Waidmann O, Choudhary C, et al.. Phosphorylation of the autophagy receptor optineurin restricts Salmonella growth. Science 2011; 333:228-33; PMID: 21617041; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1205405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Thurston TL, Wandel MP, von Muhlinen N, Foeglein A, Randow F. Galectin 8 targets damaged vesicles for autophagy to defend cells against bacterial invasion. Nature 2012; 482:414-8; PMID: 22246324; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].von Muhlinen N, Akutsu M, Ravenhill BJ, Foeglein A, Bloor S, Rutherford TJ, Freund SM, Komander D, Randow F. LC3C, bound selectively by a noncanonical LIR motif in NDP52, is required for antibacterial autophagy. Mol Cell 2012; 48:329-42; PMID: 23022382; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Philips JA. Mycobacterial manipulation of vacuolar sorting. Cell Microbiol 2008; 10:2408-15; PMID: 18783482; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].MacMicking JD, Taylor GA, McKinney JD. Immune control of tuberculosis by IFN-gamma-inducible LRG-47. Science 2003; 302:654-9; PMID: 14576437; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1088063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Campbell GR, Spector SA. Vitamin D inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in macrophages through the induction of autophagy. PLoS Pathogens 2012; 8:e1002689; PMID: 22589721; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Biswas D, Qureshi OS, Lee WY, Croudace JE, Mura M, Lammas DA. ATP-induced autophagy is associated with rapid killing of intracellular mycobacteria within human monocytes/macrophages. BMC Immunol 2008; 9:35; PMID: 18627610; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2172-9-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sanjuan MA, Dillon CP, Tait SW, Moshiach S, Dorsey F, Connell S, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Cleveland JL, Withoff S, et al.. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature 2007; 450:1253-7; PMID: 18097414; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MI, Deretic V. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 2004; 119:753-66; PMID: 15607973; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Watson RO, Manzanillo PS, Cox JS. Extracellular M. tuberculosis DNA targets bacteria for autophagy by activating the host DNA-sensing pathway. Cell 2012; 150:803-15; PMID: 22901810; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Castillo EF, Dekonenko A, Arko-Mensah J, Mandell MA, Dupont N, Jiang S, Delgado-Vargas M, Timmins GS, Bhattacharya D, Yang H, et al.. Autophagy protects against active tuberculosis by suppressing bacterial burden and inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:E3168-76; PMID: 23093667; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1210500109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chandra P, Kumar D. Selective autophagy gets more selective: Uncoupling of autophagy flux and xenophagy flux in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages. Autophagy 2016; 12:608-9; PMID: 27046255; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1080/15548627.2016.1139263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sakowski ET, Koster S, Portal Celhay C, Park HS, Shrestha E, Hetzenecker SE, Maurer K, Cadwell K, Philips JA. Ubiquilin 1 Promotes IFN-gamma-Induced Xenophagy of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS pathogens 2015; 11:e1005076; PMID: 26225865; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Li R, Tan S, Yu M, Jundt MC, Zhang S, Wu M. Annexin A2 Regulates Autophagy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection through the Akt1-mTOR-ULK1/2 Signaling Pathway. J Immunol 2015; 195:3901-11; PMID: 26371245; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1500967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ogawa M, Yoshimori T, Suzuki T, Sagara H, Mizushima N, Sasakawa C. Escape of intracellular Shigella from autophagy. Science 2005; 307:727-31; PMID: 15576571; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1106036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Baxt LA, Goldberg MB. Host and bacterial proteins that repress recruitment of LC3 to Shigella early during infection. PloS one 2014; 9:e94653; PMID: 24722587; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0094653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ogawa M, Yoshikawa Y, Kobayashi T, Mimuro H, Fukumatsu M, Kiga K, Piao Z, Ashida H, Yoshida M, Kakuta S, et al.. A Tecpr1-dependent selective autophagy pathway targets bacterial pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 2011; 9:376-89; PMID: 21575909; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Birmingham CL, Canadien V, Gouin E, Troy EB, Yoshimori T, Cossart P, Higgins DE, Brumell JH. Listeria monocytogenes evades killing by autophagy during colonization of host cells. Autophagy 2007; 3:442-51; PMID: 17568179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Yoshikawa Y, Ogawa M, Hain T, Yoshida M, Fukumatsu M, Kim M, Mimuro H, Nakagawa I, Yanagawa T, Ishii T, et al.. Listeria monocytogenes ActA-mediated escape from autophagic recognition. Nat Cell Biol 2009; 11:1233-40; PMID: 19749745; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mostowy S, Sancho-Shimizu V, Hamon MA, Simeone R, Brosch R, Johansen T, Cossart P. p62 and NDP52 proteins target intracytosolic Shigella and Listeria to different autophagy pathways. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:26987-95; PMID: 21646350; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M111.223610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Otto GP, Wu MY, Clarke M, Lu H, Anderson OR, Hilbi H, Shuman HA, Kessin RH. Macroautophagy is dispensable for intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol Microbiol 2004; 51:63-72; PMID: 14651611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Amer AO, Swanson MS. Autophagy is an immediate macrophage response to Legionella pneumophila. Cell Microbiol 2005; 7:765-78; PMID: 15888080; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00509.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Choy A, Dancourt J, Mugo B, O'Connor TJ, Isberg RR, Melia TJ, Roy CR. The Legionella effector RavZ inhibits host autophagy through irreversible Atg8 deconjugation. Science 2012; 338:1072-6; PMID: 23112293; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1227026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Horenkamp FA, Kauffman KJ, Kohler LJ, Sherwood RK, Krueger KP, Shteyn V, Roy CR, Melia TJ, Reinisch KM. The legionella anti-autophagy effector RavZ targets the autophagosome via PI3P- and curvature-sensing motifs. Dev Cell 2015; 34:569-76; PMID: 26343456; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Rolando M, Escoll P, Nora T, Botti J, Boitez V, Bedia C, Daniels C, Abraham G, Stogios PJ, Skarina T, et al.. Legionella pneumophila S1P-lyase targets host sphingolipid metabolism and restrains autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113:1901-6; PMID: 26831115; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1522067113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Mestre MB, Colombo MI. Staphylococcus aureus promotes autophagy by decreasing intracellular cAMP levels. Autophagy 2012; 8:1865-7; PMID: 23176480; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1042/BST20120167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Newton HJ, Kohler LJ, McDonough JA, Temoche-Diaz M, Crabill E, Hartland EL, Roy CR. A screen of Coxiella burnetii mutants reveals important roles for Dot/Icm effectors and host autophagy in vacuole biogenesis. PLoS Pathogens 2014; 10:e1004286; PMID: 25080348; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Gutierrez MG, Vazquez CL, Munafo DB, Zoppino FC, Beron W, Rabinovitch M, Colombo MI. Autophagy induction favours the generation and maturation of the Coxiella-replicative vacuoles. Cell Microbiol 2005; 7:981-93; PMID: 15953030; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Vazquez CL, Colombo MI. Coxiella burnetii modulates BECLIN 1 and Bcl-2, preventing host cell apoptosis to generate a persistent bacterial infection. Cell Death Differentiation 2010; 17:421-38; PMID: 19798108; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2009.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006; 19:449-90; PMID: 16847081; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1128/CMR.00054-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Terebiznik MR, Raju D, Vazquez CL, Torbricki K, Kulkarni R, Blanke SR, Yoshimori T, Colombo MI, Jones NL. Effect of Helicobacter pylori's vacuolating cytotoxin on the autophagy pathway in gastric epithelial cells. Autophagy 2009; 5:370-9; PMID: 19164948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Krakowiak MS, Noto JM, Piazuelo MB, Hardbower DM, Romero-Gallo J, Delgado A, Chaturvedi R, Correa P, Wilson KT, Peek RM Jr. Matrix metalloproteinase 7 restrains Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and premalignant lesions in the stomach by altering macrophage polarization. Oncogene 2015; 34:1865-71; PMID: 24837365; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2014.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Deen NS, Huang SJ, Gong L, Kwok T, Devenish RJ. The impact of autophagic processes on the intracellular fate of Helicobacter pylori: more tricks from an enigmatic pathogen? Autophagy 2013; 9:639-52; PMID: 23396129; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.23782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Garofalo CK, Hooton TM, Martin SM, Stamm WE, Palermo JJ, Gordon JI, Hultgren SJ. Escherichia coli from urine of female patients with urinary tract infections is competent for intracellular bacterial community formation. Infect Immun 2007; 75:52-60; PMID: 17074856; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1128/IAI.01123-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Mysorekar IU, Hultgren SJ. Mechanisms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli persistence and eradication from the urinary tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:14170-5; PMID: 16968784; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0602136103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Wang C, Mendonsa GR, Symington JW, Zhang Q, Cadwell K, Virgin HW, Mysorekar IU. Atg16L1 deficiency confers protection from uropathogenic Escherichia coli infection in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:11008-13; PMID: 22715292; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1203952109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Niu H, Xiong Q, Yamamoto A, Hayashi-Nishino M, Rikihisa Y. Autophagosomes induced by a bacterial BECLIN 1 binding protein facilitate obligatory intracellular infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:20800-7; PMID: 23197835; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1218674109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Niu H, Rikihisa Y. Ats-1: a novel bacterial molecule that links autophagy to bacterial nutrition. Autophagy 2013; 9:787-8; PMID: 23388398; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.23693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].White E. The role for autophagy in cancer. J Clin Invest 2015; 125:42-6; PMID: 25654549; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI73941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Ma Y, Galluzzi L, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Autophagy and cellular immune responses. Immunity 2013; 39:211-27; PMID: 23973220; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Galluzzi L, Pietrocola F, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Amaravadi RK, Baehrecke EH, Cecconi F, Codogno P, Debnath J, Gewirtz DA, Karantza V, et al.. Autophagy in malignant transformation and cancer progression. EMBO J 2015; 34:856-80; PMID: 25712477; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.15252/embj.201490784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Greenfield LK, Jones NL. Modulation of autophagy by Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastric carcinogenesis. Trends Microbiol 2013; 21:602-12; PMID: 24156875; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tim.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Raju D, Hussey S, Ang M, Terebiznik MR, Sibony M, Galindo-Mata E, Gupta V, Blanke SR, Delgado A, Romero-Gallo J, et al.. Vacuolating cytotoxin and variants in Atg16L1 that disrupt autophagy promote Helicobacter pylori infection in humans. Gastroenterology 2012; 142:1160-71; PMID: 22333951; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Suarez G, Romero-Gallo J, Piazuelo MB, Wang G, Maier RJ, Forsberg LS, Azadi P, Gomez MA, Correa P, Peek RM Jr. Modification of Helicobacter pylori Peptidoglycan Enhances NOD1 activation and promotes cancer of the stomach. Cancer Res 2015; 75:1749-59; PMID: 25732381; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Castano-Rodriguez N, Kaakoush NO, Goh KL, Fock KM, Mitchell HM. Autophagy in Helicobacter pylori infection and related gastric cancer. Helicobacter 2015; 20:353-69; PMID: 25664588; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1111/hel.12211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Lee CH, Lin ST, Liu JJ, Chang WW, Hsieh JL, Wang WK. Salmonella induce autophagy in melanoma by the downregulation of AKT/mTOR pathway. Gene Ther 2014; 21:309-16; PMID: 24451116; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1038/gt.2013.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Liu B, Jiang Y, Dong T, Zhao M, Wu J, Li L, Chu Y, She S, Zhao H, Hoffman RM, et al.. Blockage of autophagy pathway enhances Salmonella tumor-targeting. Oncotarget 2016; 7:22873-82; PMID: 27013582; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.18632/oncotarget.8251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Gyemant N, Molnar A, Spengler G, Mandi Y, Szabo M, Molnar J. Bacterial models for tumor development. Mini-rev Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung 2004; 51:321-32; PMID: 15571072; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1556/AMicr.51.2004.3.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Peterson AJ, Menheniott TR, O'Connor L, Walduck AK, Fox JG, Kawakami K, Minamoto T, Ong EK, Wang TC, Judd LM, et al.. Helicobacter pylori infection promotes methylation and silencing of trefoil factor 2, leading to gastric tumor development in mice and humans. Gastroenterology 2010; 139:2005-17; PMID: 20801119; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Low D, Mino-Kenudson M, Mizoguchi E. Recent advancement in understanding colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20:2115-23; PMID: 25337866; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Muhlbauer M, Tomkovich S, Uronis JM, Fan TJ, Campbell BJ, Abujamel T, Dogan B, Rogers AB, et al.. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science 2012; 338:120-3; PMID: 22903521; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1224820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Hong SK, Kim HJ, Song CS, Choi IS, Lee JB, Park SY. Nitazoxanide suppresses IL-6 production in LPS-stimulated mouse macrophages and TG-injected mice. Int Immunopharmacol 2012; 13:23-7; PMID: 22430099; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Di Santo N, Ehrisman J. A functional perspective of nitazoxanide as a potential anticancer drug. Mutat Res 2014; 768:16-21; PMID: 25847384; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Fischbach W, Goebeler-Kolve ME, Dragosics B, Greiner A, Stolte M. Long term outcome of patients with gastric marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) following exclusive Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: experience from a large prospective series. Gut 2004; 53:34-7; PMID: 14684573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Van Nuffel AM, Sukhatme V, Pantziarka P, Meheus L, Sukhatme VP, Bouche G. Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO)-clarithromycin as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience 2015; 9:513; PMID: 25729426; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.3332/ecancer.2015.513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Tang C, Yang L, Jiang X, Xu C, Wang M, Wang Q, Zhou Z, Xiang Z, Cui H. Antibiotic drug tigecycline inhibited cell proliferation and induced autophagy in gastric cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014; 446:105-12; PMID: 24582751; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Shi M, Wang HN, Xie ST, Luo Y, Sun CY, Chen XL, Zhang YZ. Antimicrobial peptaibols, novel suppressors of tumor cells, targeted calcium-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer 2010; 9:26; PMID: 20122248; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1186/1476-4598-9-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Masuelli L, Pantanella F, La Regina G, Benvenuto M, Fantini M, Mattera R, Silvestri R, Schippa S, Manzari V, Modesti A, et al.. Violacein, an indole-derived purple-colored natural pigment produced by Janthinobacterium lividum, inhibits the growth of head and neck carcinoma cell lines both in vitro and in vivo. Tumour Biol 2016; 37:3705-17; PMID: 26462840; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1007/s13277-015-4207-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Buffen K, Oosting M, Quintin J, Ng A, Kleinnijenhuis J, Kumar V, van de Vosse E, Wijmenga C, van Crevel R, Oosterwijk E, et al.. Autophagy controls BCG-induced trained immunity and the response to intravesical BCG therapy for bladder cancer. PLoS pathogens 2014; 10:e1004485; PMID: 25356988; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Kim SH, Choi YJ, Kim KY, Yu SN, Seo YK, Chun SS, Noh KT, Suh JT, Ahn SC. Salinomycin simultaneously induces apoptosis and autophagy through generation of reactive oxygen species in osteosarcoma U2OS cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016; 473:607-13; PMID: 27033598; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.03.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Hong JB, Zuo W, Wang AJ, Lu NH. Helicobacter pylori Infection Synergistic with IL-1beta Gene Polymorphisms Potentially Contributes to the Carcinogenesis of Gastric Cancer. Int J Med Sci 2016; 13:298-303; PMID: 27076787; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.7150/ijms.14239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Hattori N, Ushijima T. Epigenetic impact of infection on carcinogenesis: mechanisms and applications. Genome Med 2016; 8:10; PMID: 26823082; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1186/s13073-016-0267-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Escoll P, Rolando M, Buchrieser C. Modulation of host autophagy during bacterial infection: Sabotaging host munitions for pathogen nutrition. Front Immunol 2016; 7:81; PMID: 26973656; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]