Abstract

Objective:

Aquaporin (AQP) 1 and AQP 4 are expressed in human heart and several studies have been focused on these two aquaporins. For this purpose, the present study is aimed to research the effects of aging on AQP 1 and AQP 4 in heart tissue.

Methods:

In this study, 14 Balb/C type white mice were used. Animals were divided into two equal groups. Group I consisted of 2-month-old young animals (n=7), and group II consisted of 18-month-old animals (n=7). To determine the AQP1 and AQP4 expression in the myocardium, the heart tissue was removed to perform western blotting and immunohistochemical and histopathological evaluations.

Results:

Muscle fibers of the heart in aged animals were more irregular and loosely organized in hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) stained sections. H-score analysis revealed that AQP1 and AQP4 immunoreactivity significantly increased in heart tissues of old mice compared with those of young mice (p<0.001). In addition, AQP1 and AQP4 protein expressions in the tissues of old animals were increased significantly according to western blot analysis (p=0.018 and p<0.001 for AQP1 and AQP4, respectively).

Conclusion:

Increased AQP1 and AQP4 levels in the heart tissue may be correlated with the maintenance of water and electrolytes balance, which decreases with aging. In this context, it might be the result of a compensatory response to decreased AQP4 functions. In addition, this increase with aging as demonstrated in our study might be one of the factors that increases the tendency of ischemia in elder people.

Keywords: mouse, heart, aging, aquaporin 1, aquaporin 4

Introduction

Water is a major component of the cell in human and other living organisms; particularly, its movement across the membrane in multicellular life is of vital importance. The maintenance of homeostasis is highly dependent on the distribution of water throughout the body, pH balance, and electrolyte levels (1). Ensuring water balance in heart tissue is of great importance for cardiac functions. Even a small amount of water increase in the interstitial area leads to significant reduction in myocardial contractility (contraction power) (2). Many cardiac pathologies, including ischemia and reperfusion injury, are associated with fluid increase in cardiac tissue (2).

Referring to the studies conducted so far, although the pre- sence of aquaporin 1 (AQP1), AQP3, AQP4, AQP5, AQP7, AQP8, AQP9, AQP10, and AQP11 in the human heart was reported, only the presence of AQP1, AQP3, AQP4, and AQP7 could be demonstrated reliably (3). Particularly AQP1 and AQP4 are shown to be present in the human heart on protein levels and studies focused on these two aquaporin. Although cardiac AQP1 is mostly found in micro-vascular vessels, AQP4 was reported to be present in muscle cells in greater concentration (4).

As a result of cardiac ischemia–reperfusion studies performed on mice and rats using immunohistochemistry, PCR, and western blot studies, it was revealed that AQP1 and AQP4 expressions undergo a change both on mRNA and protein levels (5). It was also shown that AQP4, densely existing in skeletal muscle tissue, is heavily affected particularly in diseases such as dystrophies (6).

With aging, fluid loss occurs in all tissues. In some studies, it is suggested that this loss may be associated with change in density or functions of AQP. It was shown that especially in tissues such as intervertebral discs, kidneys, and salivary glands, AQP1, AQP2, AQP3, and AQP5 concentrations changed with aging (7). These changes are believed to be directly associated with physiological aging process and functional changes because of aging. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate effects of aging on AQP1 and AQP4 concentrations in heart tissue.

Methods

Animals

This study was performed in the experimental Gaziosmanpaşa University after obtaining permit of the local ethics committee (HADYEK-78). In the study, 14 Balb/C species white female mice (50–80 g) were used. The animals were divided into two equal groups of 7 mice. The groups were arranged in such a way that group I consisted of 2-month-old young animals (n=7), and group II consisted of 18-month-old animals (n=7). Before application, the mice were held at room temperature (22°C±1°C) and at 40%–50% humidity. The light pattern was set to be 12-h per day and 12-h per night. They were left free in terms of eating and drinking. The mice were kept under observation for 1 week and their daily physical examinations were performed.

Sampling method

The mice without any health problems were put to death by exsanguination under ketamine/xylazine (50/10 mg/kg) anesthesia. Because the study results may be affected by the exsanguination, euthanasia was performed in the same way for all the groups. The heart tissue was removed and half of it was stored by fast cooling in liquid nitrogen tank at –80°C for western blot application. The other half of the heart tissue was kept in 10% formalin solution to be used for immunohistochemical and histopathological evaluation.

Histological examination of heart tissue

Heart tissues were removed and kept in 10% formalin solution. After routine histologic procedures, they were embedded into paraffin; 4–5 µm thick sections were taken from paraffin-embedded tissues and stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) method. The stained sections were examined under a Zeiss Axio Lab A1 light microscope (Jenamed, Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry

Six sections with a thickness of 4–5 µm for each animal taken from paraffin blocks were placed on polylysine coated microscope slides. After the deparaffinized tissues were dehydrated by passing through graded alcohol series, they were suspended into distilled water and boiled in citrate buffer solution at pH 6 in a microwave oven (600 W) for 5 min for antigen retrieval. It was treated with H2O2 to prevent endogenous peroxidase activity. To prevent base staining, after treating with Ultra V Block (Ultra V Block, TA-125-UB, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) solution, it was incubated with primer antibody (Aquaporin 1 rabbit polyclonal IgG, Abcam, ab–15080, California, USA; Aquaporin 4 mouse monoclonal IgG, Abcam, ab–9512, Camridge, UK) for 60 min. After primary antibody application, seconder antibody (biotinylated anti-mouse IgG, Diagnostic BioSystems, KP 50A, Pleasanton, USA) was applied for 30 min, streptavidin horse- radish peroxidase was performed for 30 min, and 3-Amino-9-ethyl carbazole chromogen was applied, and counterstaining was then performed with Mayer’s hematoxylin. For the tissues prepared for negative control, phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was used instead of primer antibody, and other steps were performed similarly. The tissues that were passed through PBS and distilled water were closed with an appropriate solution. The preparations were examined, evaluated, and photographed under a research microscope (Zeiss Axio Lab A1).

Evaluation immunohistochemistry

For the evaluation of the immunoreactivity of AQP1 and AQP5, H-score analysis was used (7). Immunohistochemical staining intensities of AQP1 and AQP5 were evaluated in four categories during the H-score analysis. According to the evaluation, (0) was considered as no stain, (1+) as poor but detectable staining, (2+) as moderate staining, and (3+) as intense staining. Cells were detec- ted according to each staining intensity category and percentage values were obtained by rating the number of cells in the category of the total number of cells under the 40x objective. The total score was obtained by multiplying these percentage values with their own staining grade. When we formulize this as H-SCORE=∑Pi (i + l), “i” is staining grade and “Pi” is the percentage of cells in this staining intensity category. For evaluation of analysis, six sections for each animal were taken and five randomly selected areas were evaluated under a light microscope on each tissue section (using 40x objective). Two investigators, who were not informed about the type and source of the tissues, determined the percen- tage of cells at each intensity within these areas at different times. The combined average score of both observers was used.

Western blot technique

With tissue samples obtained from old and young mice groups, cell extracts were prepared in the sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 5 µg/mL Aprotinin, 5 µg/mL Leupeptin, and 5 µg/mL Pepstatine A). Protein measurements were performed on the prepared cell extracts and 7.5% SDS gel was also prepared. After the polymerization of the gel, the cell extracts were diluted in the sample buffer and boiled at 95°C for 5 min. For electrophoretic execution, the samples were loaded onto the gel and execution of the samples was provided under 100 V. With the samples executed in the gel, proteins were transferred into membranes by the use of semidry transfer method. The transfer will be realized at 100 V within 1 h. With the purpose of blocking proteins transferred into membrane, it was held in PBS solution (blocking solution) with 5% milk powder and 0.1% tween 20. At the end of 1-h blocking, the membrane will be incubated with primer antibodies overnight. At the end of this period, the membrane was washed 3 times using PBS solution with 0.1% Tween 20 for 5 min and seconder antibody application was performed. After membrane incubation with rabbit seconder antibody for 1 h, it was again washed 3 times using PBS solution with 0.1% Tween 20 for 5 min. ECL solution was used with the purpose of viewing and filming proteins in the membrane. Horseradish peroxidase enzyme linked to the secondary antibody catalyzes Lumigan PS-3 substrate in ECL solution. As luminol released as a result of this reaction causes radiation, this radiation was detected with special films. The resulting protein bands were compared between young and aged mice and were statistically analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with statistical software (SPSS 20; IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The homogeneity of variance was assessed using the Levene test, and normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Because the distribution of H-score values and western blot results was homogenous, the groups were compared with the independent samples t-test. Data were presented as the mean±SD and the error bars in all figures represent 95% confidence intervals of the mean values. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Histological findings

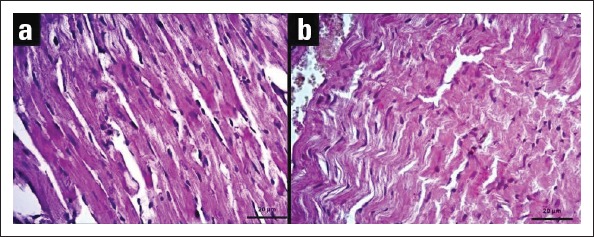

Histological structure of heart in young and aged animals were photographed with light microscopy and illustrated in Figure 1. Although normal heart tissue was observed in young mice, muscle fibers were loosely arranged and interstitial distance was increased in the aged mice. In addition, significant congestion was observed in blood vessels.

Figure 1.

Views of heart tissue sections stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E): (a) Young mouse heart tissue, (b) Old mouse heart tissue (40x objective)

Immunohistochemical findings

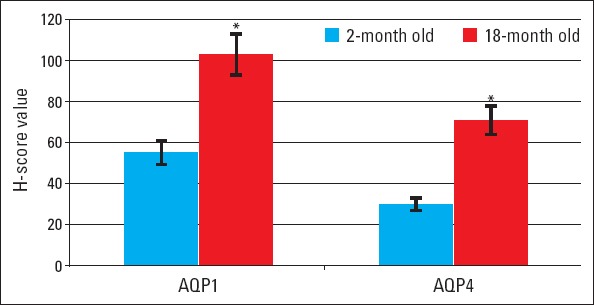

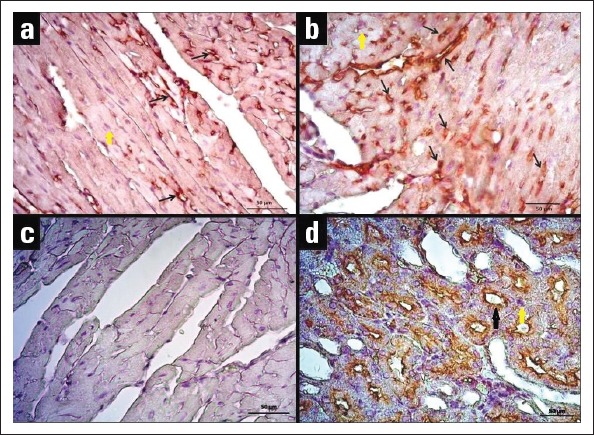

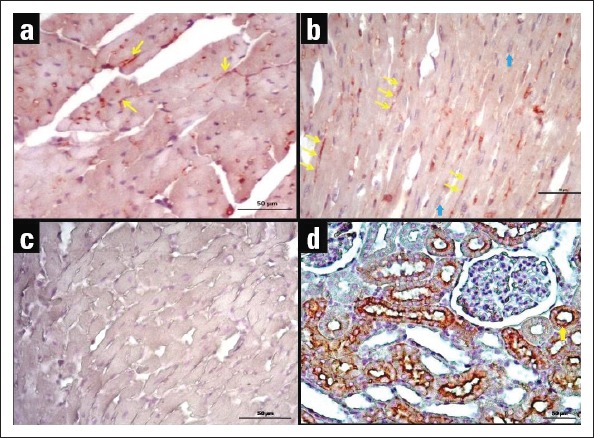

AQP1 and AQP4 proteins were immunohistochemically stained in heart tissues of young and old mice, and H-score results were evaluated and presented in Figure 2. Immunoreactivity was not observed in negative control staining. AQP4 expression was detected only in cardiomyocytes, whereas AQP1 expression was detected both in endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3, 4). H-score analysis revealed that AQP1 and AQP4 immunoreactivity significantly increased in heart tissues of old mice compared with those of young mice (p<0.001) (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

H-score values of AQP1 and AQP4 immunoreactivity. *P<0.001, compared with 2-month–old heart tissue

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of AQP1 in heart tissues of young and old mice. (a) AQP1 immunoreactivity in the heart tissue of the young mouse. (b) AQP1 immunoreactivity in the heart tissue of the old mouse. (c) Negative control staining of heart tissue. (d) Positive control staining of kidney tissue; AQP1 expression is observed in the tubules (40x objective). Black arrows point to staining of the antibody, and yellow arrow point to haematoxylin-stained

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining of AQP4 in heart tissues of young and old mice. (a) AQP4 immunoreactivity in the heart tissue of the young mouse. (b) AQP4 immunoreactivity in the heart tissue of the old mouse. AQP4 immunopositivity is observed across cardiomyocyte cell membrane. (c) Negative control staining of heart tissue. (d) Positive control staining of kidney tissue; AQP4 expression is observed in the tubules (40x objective). Yellow arrows point to staining of the antibody, and blue arrow point to haematoxylin-stained

Table 1.

H-score values by immunohistochemistry and optic densities by western blot analysis for aquaporin 1 and 4 in young (Group I) and old (Group II) mice

| Group I | Group II | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry | |||

| Aquaporin 1 | 55±7 | 103±12 | <0.001 |

| Aquaporin 4 | 30±4 | 71±10 | <0.001 |

| Western blot | |||

| Aquaporin 1 | 65±9 | 95±7 | 0.018 |

| Aquaporin 4 | 35±3 | 108±13 | <0.001 |

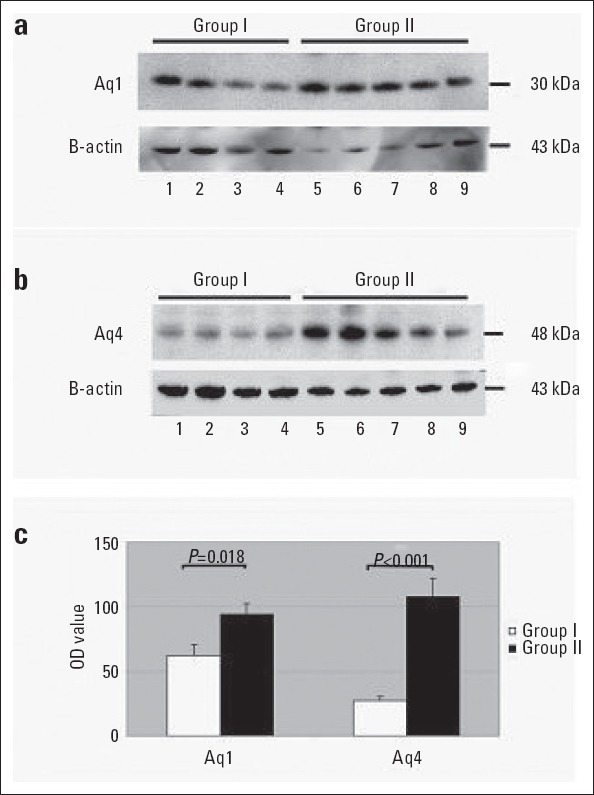

Western blot findings

With the purpose of showing AQP1 and AQP4 protein densities in heart tissues of young and old mice, a western blot analysis was performed by using anti-AQP1 and anti-AQP4 anti- bodies. Both AQP1 and AQP4 protein densities in heart tissues of old mice were reported to increase significantly compared with those of young mice (Table 1; Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Western blot analysis of aquaporin levels in the old and young mice. (a) AQP1, (b) AQP4, and (c) optic density analysis. Group I: Young mice, Group II: Old mice (P=0.018 for AQP1 and P<0.001 for AQP4)

Discussion

In this study, the expression of AQP1 and AQP4 were investigated in the hearts of young and old mice. Both western blotting and immunohistochemistry findings showed that AQP1 and AQP4 expression significantly increased in heart tissues of old mice compared with those of young mice.

Recently, potential roles of AQPs in cardiac pathophysiology were pointed out. Although AQP isoforms expressed in the human heart are reported to be AQP1, AQP3, AQP4, AQP5, AQP7, AQP8, AQP9, AQP10, and AQP11, reliable protein signals could be received for AQP1, AQP3, AQP4, and AQP7 (3). Especially AQP1 and AQP4 are considered to have roles in cardiac edema and ischemia–reperfusion damage (4). It is known that the basic water channel expressed in the hearts of mammalian species is AQP1 (8). AQP1 is present not only in cardiac endothelial cells but also in the cardiac vascular smooth muscle cells of humans and caveolae and T-tubules of rat cardiomyocytes (4). In our study, AQP1 expression is shown in the heart of old mice by western blot and immunohistochemistry method. AQP1 was determined to be expressed immunohistochemically in cardiomyocytes, particularly in cardiac endothelial cells.

The most important function of AQP1 is to provide transepithelial water flow (9, 10). It was reported that there was a distinct increase in mRNA and protein levels in the AQP1 expression in animals, which were applied cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), and that myocardial edema levels increased (11, 12). In the studies conducted with knock-out (KO) mice with deleted AQP1 gene, histomorphometric measurements revealed that there was a significant reduction in the aorta and mesenteric artery wall thickness, and the systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements obtained in after 24 h demonstrated that systolic blood pressure declined significantly but diastolic blood pressure did not change, and circadian rhythm was not disrupted. AQP4 and AQP8 expression was reported to be increased in the mice with deleted AQP1 (8). Tomassoni et al. (13) demonstrated that AQP1 and 4 expression is increased in choroid plexus epithelium and brain tissue of 6-month-old spontan hypertensive rats. Considering the reduced blood pressure observed in AQP1 KO mice, the increase in AQP1 levels in our study may be associated with increased hypertension with aging.

Aging is an irreversible, physiologically complex, and conti- nuous process. Although cardiac reserve decreases depending on age in the cardiovascular system, vascular stiffness and left ventricular diastolic function disorder occur. Anatomical chan- ges observed in the heart begin at cellular level (14). Moreover, with aging, a decrease in mitochondrial functions and an increase in free oxygen radicals is observed. This situation parti- cularly reduces endothelial nitric oxide (eNOS) levels and inhibits angiogenesis (15). Reduction in angiogenesis because of aging might have led to the increase in the AQP1 expression levels in old mice we found in our study. In terms of ensuring water balan- ce in interstitial medium and cardiac dysfunction associated with aging, it is possible that AQP1 expression levels in cardiac endothelium might be increasing as a compensatory response to the reduction in angiogenesis.

AQP4, another AQP expressed in the heart tissue, is known to have the maximum capacity, compared with other AQPs, in terms of water permeability (16). Three isoforms of AQP4, whose molecular structure is in tetramer arrays, was shown in the mouse heart with WB (17). While AQP4 was expressed at mRNA level in human, rat, and mouse hearts, protein-level expression was shown only in mouse cardiomyocytes at significant levels and in humans at minimal levels (4). In our study, the AQP4 expression was shown in the hearts of young and old mice at protein level by both western blot and immunohistochemical methods. In immunohistochemical staining, AQP4 was shown to be present in the cell membranes of cardiomyocytes. Although AQP4 function is not completely understood in many tissues, it is believed to play an important role in the mechanism of edema particularly in the brain and heart tissues (18). In the evaluation of ischemia–reperfusion injury in rat hearts made by qPCR, AQP4 mRNA level was observed to be decreased while there was no change in protein levels. In another study, it was reported that there was a significant reduction in infarct size in AQP4 KO mice after ischemia and reperfusion compared with that in wild-type mice (18).

Some studies tried to reveal the changes in other tissues rather than the heart that occur with aging and differences in AQP isoform expressions in these tissues. It was reported that AQP levels in intervertebral discs and retina change with aging (7, 19, 20). In 56,464 patients whose BOS and serum samples were evaluated, AQP4 seropositivity was distinctly higher in old patients, and in terms of gender comparison, women showed a considerably higher seropositivity than men (21). Using the brain and cerebellum tissues of mice, a study conducted with RT-PCR and WB revealed that AQP4 amounts significantly increase with aging (22). Researchers suggested that this could be associated with the maintenance of water and electrolyte balance, which decreases with aging. Consistent with the previous studies, our study demonstrated that AQP4 levels increase in the heart tissue of aged mice. It might be associated with the maintenance of reduced water and electrolyte balance because of aging. In addition, it might be the result of a compensatory response to decreased AQP4 functions. Considering that AQP4-deleted gene KO mice after ischemia and reperfusion have a significant reduction of infarct size compared with wild-type mice (18), the increase in AQP4 levels with respect to aging, as demonstrated in our study, may be one of the factors that increases the tendency of ischemia in elder people.

Study limitations

In this study, we did not examine mRNA levels of AQP1 and AQP4. In terms of strengthening our findings, mRNA levels of AQPs could be demonstrated by methods such as real-time PCR.

Conclusion

In the present study, we demonstrated an increased expression of AQP-1 and AQP-4 in 18-month-old heart tissues of mice compared with that in 2-month-old heart tissues. AQP-1 and AQP-4 may have significant roles for the development of age-related hypertension and the tendency of cardiac ischemia. Further functional studies need to clarify the main role of AQP-1 and AQP-4 in age-related cardiac pathologies. Moreover, clinical and animal research is needed to enhance our understanding about the underlying physiology, with the prospect of new therapeutical strategies in the treatment of age-related pathologies of heart tissue in the future.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship contributions: Concept – H.B., M.S.; Design – H.B., M.S.; Supervision – H.B., M.S.; Fundings – H.B., S.O., H.I.S., İ.D.; Materials – H.B., M.U., S.O., R.A.; Data collection &/or processing – H.B., M.U., H.I.S., T.A.; Analysis &/or interpretation – H.B., M.U., H.I.S., T.A.; Literature search – H.B., S.O.; Writing – H.B., R.A., İ.D.; Critical review – H.B., R.A., İ.D., T.A.

Mihri Müşfik Hanım (See page 45) was one of the first female artists of the new modern Turkey Republic and painted this portrait of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, which is over 3 meters in height, in 1922. For many years the portrait was lost, but it was found in 1990. (The Editor-in-Chief regrets that the photo was previously not properly enlarged). (From Prof. Dr. Cumhur Ertekin’s collection)

References

- 1.Guyton AC, Hall JE. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehlhorn U, Geissler HJ, Laine GA, Allen SJ. Myocardial fluid balance. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20:1220–30. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)01031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler TL, Au CG, Yang B, Egan JR, Tan YM, Hardeman EC, et al. Cardiac aquaporin expression in humans, rats, and mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H705–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00090.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rutkovskiy A, Valen G, Vaage J. Cardiac aquaporins. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:393. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutkovskiy A, Bliksoen M, Hillestad V, Amin M, Czibik G, Valen G, et al. Aquaporin-1 in cardiac endothelial cells is downregulated in isc-hemia, hypoxia and cardioplegia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;56:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Au CG, Butler TL, Egan JR, Cooper ST, Lo HP, Compton AG, et al. Changes in skeletal muscle expression of AQP1 and AQP4 in dystrophinopathy and dysferlinopathy patients. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:235–46. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0369-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taş U, Çaylı S, İnanır A, Özyurt B, Ocaklı S, Karaca ZI, et al. Aquaporin-1 and aquaporin-3 expressions in the intervertebral disc of rats with aging. Balkan Med J. 2012;29:349–53. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2012.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montiel V, Leon Gomez E, Bouzin C, Esfahani H, Romero Perez M, Lobysheva I, et al. Genetic deletion of aquaporin-1 results in microcardia and low blood pressure in mouse with intact nitric oxide-dependent relaxation, but enhanced prostanoids-dependent relaxation. Pflugers Arch. 2013;466:237–51. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verkman AS. Aquaporins in endothelia. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1120–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma T, Yang B, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS. Severely impaired urinary concentrating ability in transgenic mice lacking aquaporin-1 water channels. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4296–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding FB, Yan YM, Bao CR, Huang JB, Mei J, Liu H, et al. The role of aquaporin 1 activated by cGMP in myocardial edema caused by cardiopulmonary bypass in sheep. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;32:1320–30. doi: 10.1159/000354530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan Y, Huang J, Ding F, Mei J, Zhu J, Liu H, et al. Aquaporin 1 plays an important role in myocardial edema caused by cardiopulmonary bypass surgery in goat. Int J Mol Med. 2013;31:637–43. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomassoni D, Bramanti V, Amenta F. Expression of aquaporins 1 and 4 in the brain of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Brain Res. 2010;1325:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta D, Verma S, Pun SC, Steingart RM. The changes in cardiac physiology with aging and the implications for the treating oncologist. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6:178–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahteenvuo J, Rosenzweig A. Effects of aging on angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2012;110:1252–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.246116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warth A, Eckle T, Kohler D, Faigle M, Zug S, Klingel K, et al. Upregulation of the water channel aquaporin-4 as a potential cause of postischemic cell swelling in a murine model of myocardial infarction. Cardiology. 2007;107:402–10. doi: 10.1159/000099060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorbo JG, Moe SE, Ottersen OP, Holen T. The molecular composition of square arrays. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2631–7. doi: 10.1021/bi702146k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutkovskiy A, Stenslokken KO, Mariero LH, Skrbic B, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Hillestad V, et al. Aquaporin-4 in the heart:expression, regulation and functional role in ischemia. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107:280. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ortak H, Çaylı S, Ocaklı S, Söğüt E, Ekici F, Taş U, et al. Age-related changes of aquaporin expression patterns in the postnatal rat retina. Acta Histochem. 2013;115:382–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue N, Iida H, Yuan Z, Ishikawa Y, Ishida H. Age-related decreases in the response of aquaporin-5 to acetylcholine in rat parotid glands. J Dent Res. 2003;82:476–80. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quek AM, McKeon A, Lennon VA, Mandrekar JN, Iorio R, Jiao Y, et al. Effects of age and sex on aquaporin-4 autoimmunity. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:1039–43. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta RK, Kanungo M. Glial molecular alterations with mouse brain development and aging:up-regulation of the Kir4.1 and aquaporin-4. Age (Dordr) 2013;35:59–67. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9330-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]