Abstract

Social anxiety is a neurobehavioral trait characterized by fear and reticence in social situations. Twin studies have shown that social anxiety has a heritable basis, shared with neuroticism and extraversion, but genetic studies have yet to demonstrate robust risk variants. We conducted genomewide association analysis (GWAS) of subjects within the Army Study To Assess Risk and Resilience in Service members (Army STARRS) to (1) determine SNP-based heritability of social anxiety; (2) discern genetic risk loci for social anxiety; and (3) determine shared genetic risk with neuroticism and extraversion. GWAS were conducted within ancestral groups (EUR, AFR, LAT) using linear regression models for each of the 3 component studies in Army STARRS, and then meta-analyzed across studies. SNP-based heritability for social anxiety was significant (h2g=0.12, p=2.17×10-4 in EUR). One meta-analytically genomewide significant locus was seen in each of EUR (rs708012, Chr 6: BP 36965970, p = 1.55×10-8; beta = 0.073) and AFR (rs78924501, Chr 1: BP 88406905, p = 3.58×10-8; beta = 0.265) samples. Social anxiety in Army STARRS was significantly genetically correlated (negatively) with extraversion (rg = -0.52, se = 0.22, p = 0.02) but not with neuroticism (rg = 0.05, se = 0.22, p = 0.81) or with an anxiety disorder factor score (rg = 0.02, se = 0.32, p = 0.94) from external GWAS meta-analyses. This first GWAS of social anxiety confirms a genetic basis for social anxiety, shared with extraversion but possibly less so with neuroticism.

Keywords: anxiety, extraversion, neuroticism, social anxiety, social phobia

Introduction

Social anxiety is a dispositional trait that involves emotional discomfort and reticence in situations where an individual is subject to the scrutiny of others [Craske and Stein 2016]. Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is characterized by severe anxiety in social situations, which are therefore often avoided, resulting in distress and/or functional impairment [Heimberg et al. 2014]. SAD is among the most common of the anxiety disorders, with a 12-month prevalence in the range of 5-8% and lifetime prevalence 8-12% [Ruscio et al. 2008]. It also has an early age of onset, and is associated with the frequent subsequent accrual of comorbid mental health problems such as major depression and substance use disorders [Stein and Stein 2008].

Relatively little is known about the genetics of either social anxiety or SAD [Stein and Gelernter 2014]. We have shown in prior studies that there is a heritable basis to social anxiety [Stein et al. 2002] and SAD [Stein et al. 2001], and completed a genetic linkage study consistent with the expected polygenicity [Gelernter et al. 2004]. A recent meta-analysis of 13 cohorts (42,585 subjects) showed that genetic and non-shared environmental factors explain most of the individual differences for both social anxiety as a trait and social anxiety as a disorder [Scaini et al. 2014]. Although several candidate gene studies have reported associations with SAD and related traits (e.g., shyness) [Arbelle et al. 2003; Smoller et al. 2008], none has been satisfactorily replicated [Stein and Gelernter 2014].

The purpose of the present study is to use genomewide association methods to elucidate the genetic architecture of social anxiety. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first GWAS specifically focused on social anxiety. SAD is considered by some to be a temperamental extreme of social anxiety, though factors other than severity may play a role in distinguishing a normal-range trait from disorder [Campbell-Sills et al. 2015]. There is no doubt, however, that social anxiety is a core feature of SAD and, as such, a better understanding of the biological basis of the former will contribute to deeper knowledge about the pathophysiology of the latter [Fox and Kalin 2014].

Patients with SAD are also known to score very low on the personality trait extraversion (i.e. they are extremely “introverted”) [Bienvenu et al. 2004; Jylha et al. 2009; Watson and Naragon-Gainey 2014]. Accordingly, there may be value in exploring the genetic relationship between extraversion – a trait that has been the subject of a recent, large, genetic meta-analysis [van den Berg et al. 2016] – and social anxiety. This approach is compatible with the notion of studying an “endophenotype” for SAD, as well as with the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) tactic of studying mental disorders by focusing on their basic underlying dimensions [Cuthbert 2015].

Another personality trait, neuroticism – the recent subject of two large genetic meta-analyses [Genetics of Personality et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2016] – is thought to underlie many anxiety and depressive disorders, and the evaluation of its genetic relationship to social anxiety would also be informative. We also explored the genetic relationship of social anxiety to an anxiety disorder factor score derived in a large anxiety disorder GWAS meta-analysis [Otowa et al. 2016]. As a “negative control” we also determined the genetic relationship of social anxiety with Alzheimer's disease [Lambert et al. 2013].

Lastly, given the well-characterized phenotype of hyper-sociability and low social anxiety in Williams Syndrome [Barak and Feng 2016; Morris 2010] we reasoned that scrutiny of this region might reveal associations with social anxiety. We therefore paid particular attention to the Williams Syndrome Region (7q11.23 [70-76 Mb]) in our analyses.

Methods

Subjects

Detailed information about the design and conduct of Army STARRS is available in a separate report [Ursano et al. 2014]. The recruitment, consent, human subject and data protection procedures were approved by all collaborating organizations.

New Soldier Study (NSS)

The NSS was carried out among new soldiers at the start of their basic training at one of three Army Installations between April 2011 and November 2012. Of 39,784 NSS participants who completed the computerized self-administered questionnaire (SAQ), 33,088 (83.2%) provided blood samples. Genotyping was conducted on samples from the first half of the cohort, from which samples were selected based on phenotype (enriched for probable cases of PTSD, Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder and suicidality, and then including controls with none of these disorders) (NSS1; N = 7,999). When the remaining half of the cohort collection was completed, we selected a subset (focused on posttraumatic stress disorder and suicidal behaviors as principal targets for Army STARRS) for genotyping (NSS2; N = 2,835).

Pre/Post Deployment Survey (PPDS)

The PPDS is a multi-wave panel survey that collected baseline data (T0) from US Army soldiers in three Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs) during the first quarter of 2012, within approximately six weeks of their deployment to Afghanistan. 7,927 PPDS soldiers with eligible SAQ responses were genotyped for GWAS.

Demographics

The population, sex and age composition of our analyzed sample is shown in Table 1. As expected, the PPDS subjects were older than the new recruits in the NSS. Social anxiety factor scores and standard deviations (SD) are as shown.

Table 1. Social anxiety factor scores (by ancestry) and sex and age distributions in the samples.

| NSS1 (N = 7519) | NSS2 (N = 2700) | PPDS (N = 7109) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |

| Population | |||||||||

| European American | 4728 | 0.179 | 0.893 | 1807 | 0.240 | 0.912 | 4733 | -0.157 | 0.889 |

| African American | 1350 | 0.107 | 0.936 | 399 | 0.154 | 0.939 | 873 | -0.180 | 0.848 |

| Latino American | 1441 | 0.157 | 0.890 | 494 | 0.259 | 0.901 | 1503 | -0.180 | 0.882 |

| Sex (% male) | 82.5% | 78.7% | 94.0% | ||||||

| Age (years) | 21.0 | 3.3 | 20.3 | 3.2 | 26.0 | 5.9 | |||

Measures

The SAQ included a computerized version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview screening scales (CIDI-SC) [Kessler and Ustun 2004] but social anxiety disorder, per se, was not included. Four survey items were identified as having content validity consistent with social anxiety. These items, each scored from 1 (exactly like me) through 5 (not at all like me) were: “I am much more shy then most people”; “I am pretty quiet around people I don't know well”; “I get embarrassed easily”, and “I am an outgoing social person” (this item was reverse scored). Also included was a fifth survey item consisting of a single yes/no question (coded 5/1) with face validity for social anxiety disorder: “Were you ever in your life so painfully shy or scared of social situations, (e.g., attending a party, speaking to strangers, eating in public), that you avoided social situations whenever you could?”).

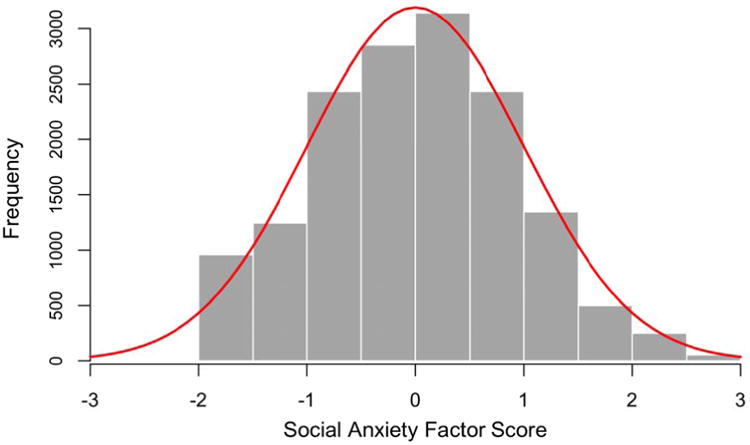

Factor analysis was used to determine the dimensionality of the 5 social anxiety items using a random sample of individuals from the NSS1 and PPDS (including all ethnic groups, therefore yielding a larger sample than analyzed here in the GWAS). The full sample (n = 14,592) was split in half to create training and testing datasets (n = 7,296 each). Exploratory factor analyses conducted using the training dataset, followed by confirmatory factor analyses conducted using the testing dataset both supported a unidimensional measurement model. Measurement invariance was assessed between the NSS1 and PPDS. The analyses indicated non-invariant item thresholds between the NSS1 and PPDS samples that was remedied by adding age as a covariate. Final parameter estimates and factor scores were computed for the combined NSS and PPDS sample (NSS1 and PPDS shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of social anxiety factor scores in the combined NSS1 and PPDS samples with a normal distribution overlay.

DNA Genotyping, Imputation and Population Stratification Adjustment

Detailed information on genotyping, genotype imputation, population assignment and principal component analysis for population stratification adjustment are included in our previous report [Stein et al. 2016] and in Supplementary Materials. Whole blood samples were shipped to Rutgers University Cell & DNA Repository (RUCDR), where they were frozen for later DNA extraction using standard methods. NSS1 and PPDS samples were genotyped using the Illumina OmniExpress + Exome array with additional custom content. NSS2 samples were genotyped on the Ilumina PsychChip.

Relatedness testing was carried out with PLINK v1.90 [Chang et al. 2015; Purcell et al. 2007] and pairs of subjects with π of >0.2 were identified; one member of each relative pair was removed at random. Genotype imputation was performed with a 2-step pre-phasing/imputation approach with a reference multi-ethnic panel from 1000 Genomes Project (August 2012 phase 1 integrated release; 2,186 phased haplotypes with 40,318,245 variants). We removed SNPs that were not present in the 1000 Genomes Project reference panel, had non-matching alleles to 1000 Genome Project reference, or had ambiguous, unresolvable alleles (AT/GC SNPs with minor allele frequency [MAF] > 0.1). A total of 664,457 SNPs for the Illumina OmniExpress array and 360,704 for the Illumina PsychChip entered the imputation procedure.

Since the Army STARRS subjects are from various ancestral backgrounds, we first assigned our samples into major population groups (European [EUR], African [AFR] or Latino [LAT]) (see Supplementary Materials for details of population assignment procedure; also see [Stein et al. 2016]). We excluded an Asian [ASI] group that was too small for separate analysis based on principal components (PCs). We then obtained PCs within each population group for population stratification adjustment (see also Supplementary Materials). We performed the following quality control (QC) procedure to obtain the genotype data for population assignment and principal component analysis (PCA). We kept autosomal SNPs with missing rate < 0.05; kept samples with individual-wise missing rate < 0.02; kept SNPs with missing rate < 0.02; and kept SNPs with missing rate difference between PTSD cases and controls < 0.02 (to minimize the bias due to differences in genotyping across PTSD cases and controls according to our sampling scheme). After QC, we merged our study samples with HapMap3 samples. We kept SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.01 and performed LD pruning at R2 > 0.02. Finally, we excluded SNPs in the MHC region (Chr 6:25-35Mb) and Chr 8 inversion (Chr 8:7-13Mb).

Statistical Analysis

GCTA [Yang et al. 2011] with imputed data (modified from [Chen et al. 2015; Yang et al. 2015]) was used to estimate the proportion of variance in social anxiety scores explained by common SNPs (i.e., SNP-heritability, h2g). We calculated the genetic relationship matrix with PLINK v1.90 on combined samples across 3 studies within each of the 3 populations (EUR, LAT, and AFR). We estimated h2g of social anxiety with linear mixed models implemented in GCTA software, adjusted for 10 PCs, study, and gender. We further stratified the sample by gender and estimated gender-specific h2g. P-value and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each h2g estimate. Given the small proportion of women in our sample, the calculation of female-specific h2g estimate is likely to be underpowered and should be interpreted in that light. Finally, we performed stratified LDSC to detect enrichment of h2g in functional annotation domains. We used 24 predefined annotation domains as described in [Finucane et al. 2015]. We estimated the enrichment of h2g for each functional annotation domain with block jackknife standard error.

PLINK v1.90 [Chang et al. 2015; Purcell et al. 2007] was used to perform genomewide association tests for social anxiety factor scores (SOCANX) on imputed SNP dosage with linear regression adjusted for the top 10 within-population principal components (PCs). We considered adjusting these analyses for other traits that influenced the sampling in NSS1 and NSS2, but the complexity of those sampling schemes (e.g., enriched for multiple disorders) did not lend itself to the derivation of a suitable set of covariates; this may be considered a limitation of the current analyses. We filtered out SNPs with MAF < 0.01 or imputation quality score (INFO) < 0.8. GWAS was conducted in the three studies (NSS1, NSS2 and PPDS) separately within each of the three ancestral groups (EUR, AFR, LAT) and then meta-analyzed within ancestry group but across studies. We report fixed-effects models as our primary analysis in the Results, but random-effects models yielded virtually identical results and I2 values and p-values for heterogeneity across studies supported the use of fixed-effects models (see Supplementary Materials).

Meta-analysis was conducted using an inverse variance-weighted fixed effects model in PLINK. A p-value of 5 × 10-8 was used as the threshold for genomewide significance. The meta-analysis of all 3 studies within ancestral groups is the primary analysis.

We used LD score regression (LDSC) [Bulik-Sullivan et al. 2015] to test the genetic correlation between social anxiety and other traits in European samples using recently published meta-analytic GWAS for anxiety disorders [Otowa et al. 2016], neuroticism [Genetics of Personality et al. 2015], and extraversion [van den Berg et al. 2016], respectively. As a negative control, we also tested the genetic correlation between social anxiety and Alzheimer's disease [Lambert et al. 2013].

We performed gene-set analysis (GSA), or pathway analysis, using software INRICH [Lee et al. 2012] to identify enriched association signals of social anxiety in gene sets aggregated in biological pathways. We used the clumping functionality (R2 threshold was 0.5) in PLINK1.9 to identify LD-independent regions based on index SNPs with p-value < 0.0001 in the final meta-analysis in European American samples.

Results

SNP-based heritability of Social Anxiety Phenotype

We estimated SNP-based heritability (h2g) using GCTA [Yang et al. 2011]. We found significant h2g estimates of 12% for social anxiety (SOCANX), seen in the meta-analysis across studies in the European American sample (p=2.17×10-4; 95% CI: 0.05 to 0.18). The h2g estimate is 12% (p=0.176, 95% CI: 0.14 to 0.38) in the African American sample and 21% (p=0.020, 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.41) in the Latino American sample, but neither was statistically significant after multiple comparison correction. The male-specific h2g estimate of social anxiety for European Americans is 14% with a significant p-value of 8.77×10-5 (95% CI: 0.07 to 0.21), while the female-specific h2g estimate is 15% with p-value of 0.323. Details of these analyses, by ancestral group and sex, are included in Table 2.

Table 2. SNP-based heritability of social anxiety (meta-analysis across NSS1, NSS2, PPDS).

| h2g | SE (h2g) | P-value | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All samples | EUR | 0.12 | 0.033 | 2.17×10-4 | 0.05 | 0.18 |

| AFR | 0.12 | 0.134 | 0.176 | -0.14 | 0.38 | |

| LAT | 0.21 | 0.102 | 0.020 | 0.01 | 0.41 | |

| Male | EUR | 0.14 | 0.037 | 8.77×10-5 | 0.07 | 0.21 |

| AFR | 0.17 | 0.174 | 0.148 | -0.17 | 0.52 | |

| LAT | 0.19 | 0.117 | 0.047 | -0.04 | 0.42 | |

| Female | EUR | 0.15 | 0.316 | 0.323 | -0.47 | 0.77 |

| AFR | 0.28 | 0.490 | 0.291 | -0.68 | 1.24 | |

| LAT | 0.67 | 0.627 | 0.158 | -0.55 | 1.90 | |

h2g: SNP-based heritability; SE: standard error; CI: confidence interval; EUR: European American; AFR: African American; LAT: Latino American. All models adjusted for 10 PCs and study components. The all samples model additionally adjusted for gender.

Enrichment of SNP-based Heritability by Functional Annotation

We estimated the enrichment of h2g by 24 main annotation domains for social anxiety. The h2g for each of the 24 annotation domains were simultaneous estimated using the association analysis summary results from the meta-analysis of European American samples in PPDS, NSS1 and NSS2. We did 2 functional enrichment analyses, one based on the “full baseline model” that is not cell type specific and the other that is central nervous system (CNS) specific. Both models showed very similar results and we did not observe any significant enrichment of h2g by functional annotation (See Supplementary Materials).

Genomewide Association Analyses

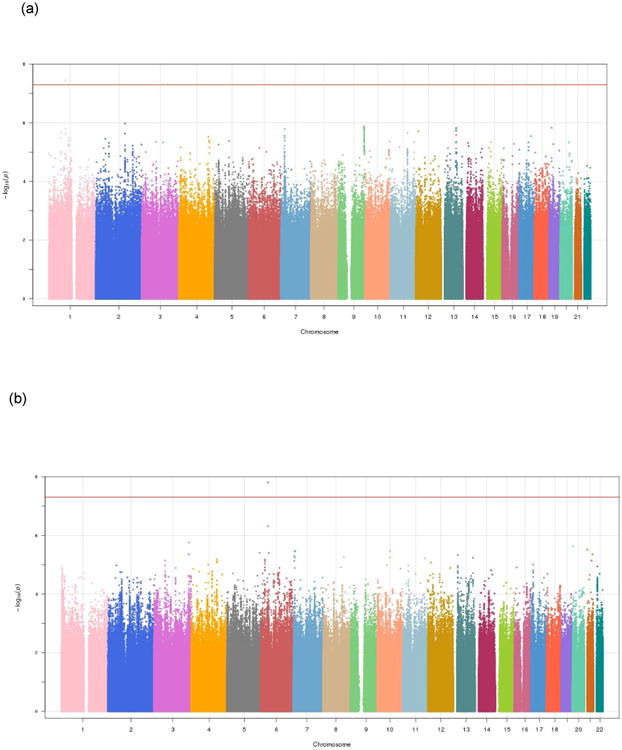

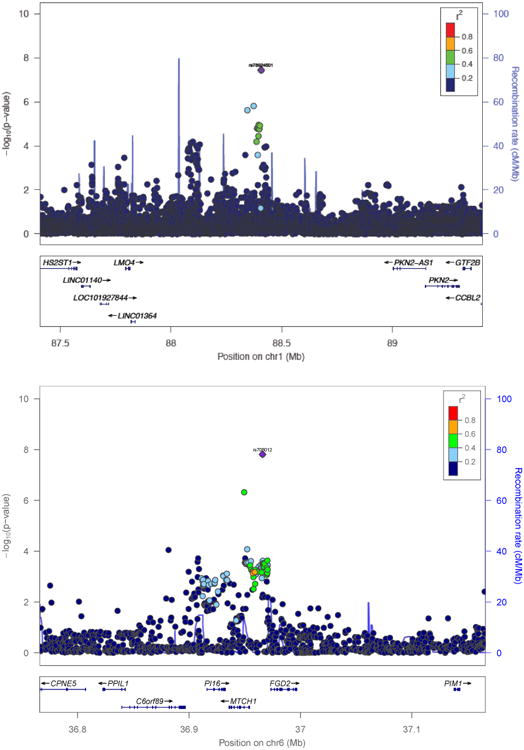

One SNP on chromosome 1 (rs78924501, BP 88406905, p = 3.58 × 10-8; beta = 0.265) was genomewide significantly associated with SOCANX in the meta-analysis across the 3 studies in the AFR subsample (Figure 2a and 3a). One SNP on chromosome 6 (rs708012, BP 36965970, p = 1.55 × 10-8; beta = 0.073) was genomewide significantly associated with SOCANX in the meta-analysis across the 3 studies in the European American sample (Figure 2b and 3b). Whereas these results were obtained using fixed effects analysis, random effects analyses identified the same two SNPs, respectively, as genomewide significant (see Supplementary Materials). We did not find similar results for either SNP in the other ancestry groups or in any of the trans-ethnic meta-analyses (Table 4; results at p < 10-6 shown).

Figure 2. Manhattan plots of NSS1, NSS2, and PPDS meta-analysis in (a) African American and (b) European American samples.

(a). African American samples, identifying genome-wide significant association for social anxiety with rs78924501 on Chr 1 (λGC = 1.013)

(b). European American samples, identifying a genome-wide significant association for social anxiety with rs708012 on Chr 6 (λGC = 1.020)

Figure 3. Regional plots of (a, top panel) rs78924501 on Chr 1 in African American subjects and (b, bottom panel) rs708012 on Chr 6 in European American subjects.

Table 4. LDSC determination of genetic correlation in EUR subjects of social anxiety score with other traits (from external study meta-analyses with PubMed ID [PMID] shown).

| Phenotype | PMID | rg | SE (rg) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety disorder (factor score) | 26754954 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.94 |

| Neuroticism | 25993607 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.81 |

| Extraversion | 26362575 | -0.52 | 0.22 | 0.02 |

| Alzheimer's Disease | 24162737 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.79 |

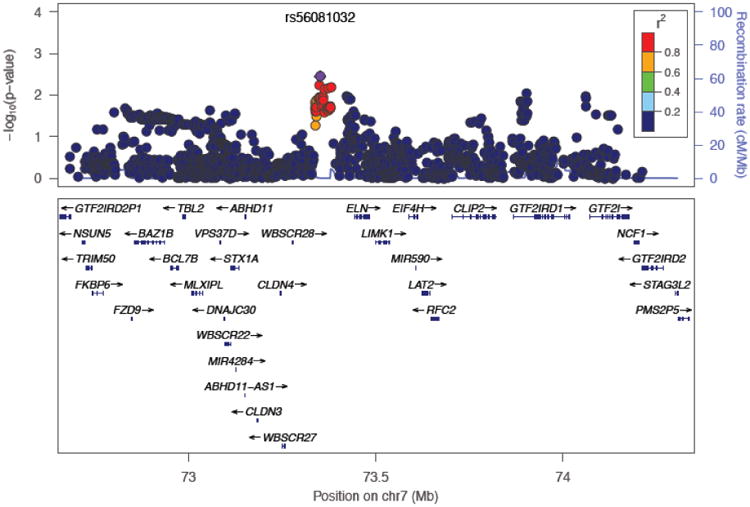

Examination of the Williams Syndrome (WS) Region (Figure 4) revealed several SNPs that were nominally significantly associated with SOCANX, the strongest association being found for rs56081032 (MAF = 0.17, p = 3.55×10−3). However, a set-based permutation test of association of SNPs in the WS region (defined as 72.5-74.5 MB), conducted using PLINK [Purcell et al. 2007], showed no statistically significant association between the WS region and social anxiety (data available from authors upon request).

Figure 4. Regional plot of rs56081032 (within the Williams Syndrome region) in European Americans.

Genetic Correlations

LDSC

Social anxiety was significantly – and negatively – genetically correlated with extraversion [van den Berg et al. 2016] (rg = - 0.52, se = 0.22, p = 0.02) in European samples. Genetic correlations with neuroticism [Genetics of Personality et al. 2015] and with an anxiety disorders quantitative factor score (derived from a multivariate analysis combining information across various anxiety disorder clinical phenotypes) [Otowa et al. 2016] were of smaller magnitude (rg = 0.05 to 0.22) and not statistically significant (Table 4). Genetic correlation with Alzheimer's disease [Lambert et al. 2013], intended as a “negative control”, was, as anticipated, small and not statistically significant (rg = 0.06, se = 0.23, p = 0.79).

Gene Set Analysis (GSA)

We identified 103 genomic regions showed association signals with social anxiety through PLINK clumping function. We tested for enrichment of genes from a certain gene-set (pathway) in these 103 genomic regions. We performed the enrichment test based on 3425 pathways from the Gene Ontology (GO) database, each with 5 to 200 genes. Pathways showed suggestive enrichment p-value (nominal p-value < 0.05) are shown (Table 5); no pathway had a statistically significant p-value after multiple testing correction.

Table 5. Gene-set analysis using INRICH to enrich association signals for social anxiety.

| Pathway | Go ID | Size | Overlap | P-value | Corrected P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| estrogen_metabolic_process | GO:0008210 | 10 | 4 | 0.0002 | 0.127 |

| luteinization | GO:0001553 | 7 | 3 | 0.0017 | 0.617 |

| S-adenosylhomocysteine_metabolic_process | GO:0046498 | 6 | 3 | 0.0046 | 0.876 |

| BRCA1-A_complex | GO:0070531 | 6 | 3 | 0.018 | 0.994 |

| lung_alveolus_development | GO:0048286 | 23 | 3 | 0.023 | 0.997 |

| anterior/posterior_pattern_formation | GO:0009952 | 96 | 7 | 0.024 | 0.997 |

| phosphoinositide_3-kinase_cascade | GO:0014065 | 10 | 3 | 0.033 | 0.999 |

| insulin-like_growth_factor_binding | GO:0005520 | 19 | 3 | 0.035 | 0.999 |

| respiratory_gaseous_exchange | GO:0007585 | 27 | 4 | 0.037 | 0.999 |

| chromatin_remodeling | GO:0006338 | 45 | 5 | 0.041 | 0.999 |

| positive_regulation_of_actin_filament_polymerization | GO:0030838 | 14 | 3 | 0.043 | 1.000 |

| multicellular_organism_growth | GO:0035264 | 25 | 3 | 0.046 | 1.000 |

Size: number of genomic regions defining the pathway; Overlap: number of LD-independent social anxiety associated regions that overlap with the genomic regions defining the pathway; P-value: nominal p-value for enrichment with 1000000 permutations; Corrected p-value: p-value after multiple testing correction.

Discussion

This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first GWAS of social anxiety conducted to date. Consistent with prior twin studies, but using GWAS methods to calculate SNP-based heritability, we confirmed that social anxiety has a heritable basis. The magnitude of heritability we found is in the range of that found using the same methods for other traits such as neuroticism (15%) [Smith et al. 2016]. According to twin studies, genetic factors that influence individual variation in extraversion and neuroticism appear to account entirely for the genetic risk for SAD [Bienvenu et al. 2007], highlighting the value of examining the molecular genetic determinants of both these traits as a means to identifying risk loci for SAD. A large meta-analysis of GWAS datasets for extraversion identified no genomewide significant loci, nor did a significant SNP-based heritability estimate emerge [van den Berg et al. 2016]. Recent meta-analyses of genomewide association studies (GWAS) have revealed genomewide significant loci for neuroticism [Genetics of Personality et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2016] and it might be expected that risk loci for these traits might overlap with those for SAD.

Interestingly, consistent with the high negative phenotypic correlation between social anxiety and extraversion seen in the literature [Bienvenu et al. 2004; Jylha et al. 2009; Watson and Naragon-Gainey 2014], using LDSC we found evidence in our European samples of a strong and statistically significant negative genetic correlation between social anxiety in our study and extraversion in a published GWAS meta-analysis dataset [van den Berg et al. 2016]. In contrast, we failed to find evidence of a significant genetic correlation between social anxiety in our study and neuroticism in a published neuroticism GWAS meta-analysis dataset [Genetics of Personality et al. 2015]. It is conceivable that failure to find genetic correlations between social anxiety and neuroticism is a result of inadequate power, although the external GWAS for neuroticism and extraversion were both large (N > 60,000 subjects) and, in fact, included the same subjects. But it is also possible that despite considerable shared phenotypic variance, the shared genetic variance between social anxiety and extraversion is larger than that shared between social anxiety and neuroticism. Larger social anxiety samples will be needed to resolve this issue.

There have also been GWAS studies of internalizing disorders (which would include SAD) [Hettema et al. 2015] and GWAS [Otowa et al. 2014] and meta-analytic reports of GWAS [Otowa et al. 2016] of anxiety disorders (which would also include SAD). As such, risk loci detected in those studies could be relevant to social anxiety and SAD, but this possibility cannot be determined from those studies because they did not specifically examine social anxiety phenotypes. We failed, in fact, to find a significant genetic correlation between an anxiety disorder factor from the aforementioned anxiety disorder GWAS [Otowa et al. 2016] and social anxiety. It is uncertain to what extent genetic risk for the dimensional trait studied here maps onto the disorder (i.e., SAD). It will be important for future research to examine the risk loci identified in our study (rs78924501 on Chr1 in the AFR sample, and rs708012 on Chr6 in the EUR sample) for their possible association with SAD and other anxiety-related disorders. Of particular note, the Chr1 risk SNP is downstream from CCBL2, also known as KYAT3 (Kynurenine Aminotransferase 3), which encodes an aminotransferase involved in the metabolism of tryptophan. KYAT3 variation has previously been described in relation to risk for major depression [Claes et al. 2011]. Abnormal brain tryptophan metabolism and its possible relationship to altered serotonin synthesis and signaling have been at the forefront of recent hypotheses about the pathophysiology of SAD [Frick et al. 2015; Stein and Andrews 2015], with another tryptophan metabolic pathway gene, TPH2 (tryptophan hydroxylase 2) recently implicated as a risk locus [Furmark et al. 2016]. Taken together, these observations call for additional studies of a role for genetic variation in serotonin signaling pathways in social anxiety and SAD.

Individuals with Williams syndrome (WS), caused by hemizygous microdeletion of a portion of 7q11.23, have a behavioral phenotype that includes extreme gregariousness and hypersociability [Barak and Feng 2016; Morris 2010]. As such, WS presents a remarkable mirror image of the behavioral phenotype of SAD. Accordingly, we decided to pay particular attention to the Williams region as part of our analysis. A region-based test of SNPs in this region failed to find evidence of significant association. Nevertheless, we found nominally significant association with several SNPs in the Williams region (the most significant of which was rs56081032 (MAF = 0.17, p = 3.55×10−3). This SNP is approximately 600 Kb upstream from another gene in the Williams Region, GTF2I, variants in which have been suggested to influence extraversion and anxiety proneness in healthy adults [Jabbi et al. 2015; Swartz et al. 2015]. These observations suggest that it may be fruitful to scrutinize the Williams region more carefully, in order to fully test the hypothesis that copy-number variants in this region might influence risk for disorders associated with elevated social anxiety (e.g., SAD).

Our results should be interpreted in light of several additional limitations. First, samples sizes – especially within ancestral groups – are likely to be insufficiently powered to detect loci of modest effect. Much larger samples will be needed to discern genes of smaller effect. Second, the publicly available external GWAS datasets to which we had access consisted solely of individuals of European descent, and it is therefore possible that the conclusions we have drawn regarding genetic correlations may apply only to that tested ancestral group. Third, it is important to remember that our focus here has been on social anxiety as a continuous trait. Although we believe that understanding the genetic architecture of social anxiety and its relationship to other traits will be informative toward the understanding of a disorder marked by heightened levels of social anxiety, namely SAD, this is an empirical question that can only be answered by direct application of our findings to samples of patients with SAD and other anxiety disorders. Fourth, our sample is mostly male, but SAD has a strong female predominance. It may be that the genetic factors influencing SAD vary by sex, although our failure to obtain a statistically significant heritability estimate in women is almost certainly due to low power for this sex-specific analysis. Fifth, our sample is entirely military, and it is possible that generalizability to the general population is limited.

In summary, this first GWAS of social anxiety confirms a genetic basis for social anxiety, shared with extraversion but possibly less so with neuroticism. Scrutiny of the Williams Region for copy-number variants relevant to social anxiety should be attempted. Such studies hold the promise of leading to a better understanding of risk for early-onset disorders such as social anxiety disorder and related conditions.

Supplementary Material

Table 3. NSS1, NSS2 and PPDS GWAS Meta-analysis Results at p < 10-6.

| CHR | BP | SNP | A1 (MAF) | A2 | BETA | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFR | |||||||

| 1 | 88406905 | rs78924501 | T (0.09) | C | 0.265 | 3.58×10-8* | |

| EUR | |||||||

| 6 | 36949527 | rs2293390 | T (0.42) | C | 0.0613 | 4.80×10-07 | |

| 6 | 36965970 | rs708012 | T (0.32) | C | 0.0732 | 1.55×10-8* | |

| LAT | |||||||

| 7 | 49136131 | rs35200331 | T (0.148) | C | 0.1482 | 2.25×10-7 | |

| 7 | 70464765 | rs74820377 | T (0.186) | C | 0.1859 | 7.71×10-7 | |

| 11 | 89078387 | rs60391512 | T (0.390) | C | 0.3900 | 7.48×10-7 | |

| 12 | 108618081 | rs117328207 | T (0.641) | C | 0.6412 | 4.94×10-7 | |

| ALL | 1 | 88406905 | rs78924501 | T (0.241) | C | 0. 2414 | 1. 97×10-7 |

| 6 | 97374850 | rs13203153 | A (0.061) | G | 0. 0606 | 3. 08×10-7 | |

| 6 | 97391272 | rs2223614 | A (0.062) | C | 0. 0619 | 2. 40×10-7 | |

| 6 | 97404417 | rs34663994 | A (0.058) | C | 0. 0583 | 8. 32×10-7 | |

MAF = Minor allele frequency

P < 5 × 10-8

Acknowledgments

Funding: Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number U01MH087981 (MBS and RJU) with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIMH, the Veterans Administration, Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Access to Data and Data Analysis: Murray B. Stein MD, MPH had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Stein, Chen, Gelernter, Jain, Jensen, Maihofer, Polimanti, Ripke, Smoller, and Wang, as well as Ms. Sun, conducted and are jointly responsible for the data analysis.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Dr. Stein has in the last 3 years been a consultant for Healthcare Management Technologies, and Actelion, Dart Neuroscience, Janssen, Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Resilience Therapeutics, and Tonix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Kessler has in the last 3 years been a consultant for Hoffman-La Roche, Inc., Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, and Sanofi-Aventis Groupe. Dr. Kessler has served on advisory boards for Mensante Corporation, Plus One Health Management, Lake Nona Institute, and U.S. Preventive Medicine. Dr. Kessler owns 25% share in DataStat, Inc. Dr. Smoller is an unpaid member of the Scientific Advisory Board of PsyBrain, Inc. The remaining authors report no disclosures.

Army STARRS Collaborative Team Members: The Army STARRS Team consists of Co-Principal Investigators: Robert J. Ursano, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) and Murray B. Stein, MD, MPH (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System); Site Principal Investigators: Steven G. Heeringa, PhD (University of Michigan) and Ronald C. Kessler, PhD (Harvard Medical School); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) collaborating scientists: Lisa J. Colpe, PhD, MPH and Michael Schoenbaum, PhD; Army liaisons/consultants: COL Steven Cersovsky, MD, MPH (USAPHC) and Kenneth Cox, MD, MPH (USAPHC). Other team members: Pablo A. Aliaga, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); COL David M. Benedek, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); K. Nikki Benevides, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul D. Bliese, PhD (University of South Carolina); Susan Borja, PhD (NIMH); Evelyn J. Bromet, PhD (Stony Brook University School of Medicine); Gregory G. Brown, PhD (University of California San Diego); Christina Buckley, BA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Laura Campbell-Sills, PhD (University of California San Diego); Tianxi Cai, ScD (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health); Chia-Yen Chen, ScD (Massachusetts General Hospital); Catherine L. Dempsey, PhD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Julie O. Denenberg MA (University of California San Diego); Carol S. Fullerton, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Nancy Gebler, MA (University of Michigan); Joel Gelernter MD (Yale University); Robert K. Gifford, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Stephen E. Gilman, ScD (Harvard School of Public Health); Feng He (University of California San Diego); Marjan G. Holloway, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul E. Hurwitz, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Sonia Jain, PhD (University of California San Diego); Tzu-Cheg Kao, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Karestan C. Koenen, PhD (Columbia University); Kevin P. Jensen, PhD (Yale University); Lisa Lewandowski-Romps, PhD (University of Michigan); Holly Herberman Mash, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Adam X. Maihofer MS (University of California San Diego); James E. McCarroll, PhD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Colter Mitchell, PhD (University of Michigan); James A. Naifeh, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Tsz Hin Hinz Ng, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Matthew K. Nock, PhD (Harvard University); Rema Raman, PhD (University of California San Diego); Holly J. Ramsawh, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Anthony Joseph Rosellini, PhD (Harvard Medical School); Nancy A. Sampson, BA (Harvard Medical School); LCDR Patcho Santiago, MD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Michaelle Scanlon, MBA (NIMH); Jordan W. Smoller, MD, ScD (Massachusetts General Hospital); Amy Street, PhD (Boston University School of Medicine); Xiayong Sun, MS (University of California San Diego); Michael L. Thomas, PhD (University of California San Diego); Patti L. Vegella, MS, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Leming Wang, MS (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Erin Ware, PhD (University of Michigan); Christina L. Wassel, PhD (University of Pittsburgh); Simon Wessely, FMedSci (King's College London); Hongyan Wu, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); LTC Gary H. Wynn, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Alan M. Zaslavsky, PhD (Harvard Medical School); Bailey G. Zhang, MS (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); and Lei Zhang, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences).

References

- Arbelle S, Benjamin J, Golin M, Kremer I, Belmaker RH, Ebstein RP. Relation of shyness in grade school children to the genotype for the long form of the serotonin transporter promoter region polymorphism. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(4):671–676. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak B, Feng G. Neurobiology of social behavior abnormalities in autism and Williams syndrome. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(6):647–655. doi: 10.1038/nn.4276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu OJ, Hettema JM, Neale MC, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Low extraversion and high neuroticism as indices of genetic and environmental risk for social phobia, agoraphobia, and animal phobia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1714–1721. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu OJ, Samuels JF, Costa PT, Reti IM, Eaton WW, Nestadt G. Anxiety and depressive disorders and the five-factor model of personality: a higher- and lower-order personality trait investigation in a community sample. Depress Anxiety. 2004;20(2):92–97. doi: 10.1002/da.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Anttila V, Gusev A, Day FR, Loh PR, Duncan L, Perry JR, Patterson N, Robinson EB, Daly MJ, Price AL, Neale BM ReproGen C, Psychiatric Genomics C, Genetic Consortium for Anorexia Nervosa of the Wellcome Trust Case Control C. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat Genet. 2015;47(11):1236–1241. doi: 10.1038/ng.3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Espejo E, Ayers CR, Roy-Byrne P, Stein MB. Latent dimensions of social anxiety disorder: A re-evaluation of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) J Anxiety Disord. 2015;36:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MH, Pan TL, Li CT, Lin WC, Chen YS, Lee YC, Tsai SJ, Hsu JW, Huang KL, Tsai CF, Chang WH, Chen TJ, Su TP, Bai YM. Risk of stroke among patients with post-traumatic stress disorder: nationwide longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.143610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes S, Myint AM, Domschke K, Del-Favero J, Entrich K, Engelborghs S, De Deyn P, Mueller N, Baune B, Rothermundt M. The kynurenine pathway in major depression: haplotype analysis of three related functional candidate genes. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188(3):355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Stein MB. Anxiety. Lancet 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN. Research Domain Criteria: toward future psychiatric nosologies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17(1):89–97. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.1/bcuthbert. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane HK, Bulik-Sullivan B, Gusev A, Trynka G, Reshef Y, Loh PR, Anttila V, Xu H, Zang C, Farh K, Ripke S, Day FR, Purcell S, Stahl E, Lindstrom S, Perry JR, Okada Y, Raychaudhuri S, Daly MJ, Patterson N, Neale BM, Price AL ReproGen C, Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C, Consortium R. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat Genet. 2015;47(11):1228–1235. doi: 10.1038/ng.3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AS, Kalin NH. A translational neuroscience approach to understanding the development of social anxiety disorder and its pathophysiology. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(11):1162–1173. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14040449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick A, Ahs F, Engman J, Jonasson M, Alaie I, Bjorkstrand J, Frans O, Faria V, Linnman C, Appel L, Wahlstedt K, Lubberink M, Fredrikson M, Furmark T. Serotonin Synthesis and Reuptake in Social Anxiety Disorder: A Positron Emission Tomography Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):794–802. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furmark T, Marteinsdottir I, Frick A, Heurling K, Tillfors M, Appel L, Antoni G, Hartvig P, Fischer H, Langstrom B, Eriksson E, Fredrikson M. Serotonin synthesis rate and the tryptophan hydroxylase-2: G-703T polymorphism in social anxiety disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0269881116648317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Page GP, Stein MB, Woods SW. Genome-wide linkage scan for loci predisposing to social phobia: evidence for a chromosome 16 risk locus. The American journal of psychiatry. 2004;161(1):59–66. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genetics of Personality C. de Moor MH, van den Berg SM, Verweij KJ, Krueger RF, Luciano M, Arias Vasquez A, Matteson LK, Derringer J, Esko T, Amin N, Gordon SD, Hansell NK, Hart AB, Seppala I, Huffman JE, Konte B, Lahti J, Lee M, Miller M, Nutile T, Tanaka T, Teumer A, Viktorin A, Wedenoja J, Abecasis GR, Adkins DE, Agrawal A, Allik J, Appel K, Bigdeli TB, Busonero F, Campbell H, Costa PT, Davey Smith G, Davies G, de Wit H, Ding J, Engelhardt BE, Eriksson JG, Fedko IO, Ferrucci L, Franke B, Giegling I, Grucza R, Hartmann AM, Heath AC, Heinonen K, Henders AK, Homuth G, Hottenga JJ, Iacono WG, Janzing J, Jokela M, Karlsson R, Kemp JP, Kirkpatrick MG, Latvala A, Lehtimaki T, Liewald DC, Madden PA, Magri C, Magnusson PK, Marten J, Maschio A, Medland SE, Mihailov E, Milaneschi Y, Montgomery GW, Nauck M, Ouwens KG, Palotie A, Pettersson E, Polasek O, Qian Y, Pulkki-Raback L, Raitakari OT, Realo A, Rose RJ, Ruggiero D, Schmidt CO, Slutske WS, Sorice R, Starr JM, St Pourcain B, Sutin AR, Timpson NJ, Trochet H, Vermeulen S, Vuoksimaa E, Widen E, Wouda J, Wright MJ, Zgaga L, Porteous D, Minelli A, Palmer AA, Rujescu D, Ciullo M, Hayward C, Rudan I, Metspalu A, Kaprio J, Deary IJ, Raikkonen K, Wilson JF, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L, Bierut LJ, Hettema JM, Grabe HJ, van Duijn CM, Evans DM, Schlessinger D, Pedersen NL, Terracciano A, McGue M, Penninx BW, Martin NG, Boomsma DI. Meta-analysis of Genome-wide Association Studies for Neuroticism, and the Polygenic Association With Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(7):642–650. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Hofmann SG, Liebowitz MR, Schneier FR, Smits JA, Stein MB, Hinton DE, Craske MG. Social anxiety disorder in DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(6):472–479. doi: 10.1002/da.22231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, Chen X, Sun C, Brown TA. Direct, indirect and pleiotropic effects of candidate genes on internalizing disorder psychopathology. Psychol Med. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbi M, Chen Q, Turner N, Kohn P, White M, Kippenhan JS, Dickinson D, Kolachana B, Mattay V, Weinberger DR, Berman KF. Variation in the Williams syndrome GTF2I gene and anxiety proneness interactively affect prefrontal cortical response to aversive stimuli. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e622. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylha P, Melartin T, Isometsa E. Relationships of neuroticism and extraversion with axis I and II comorbidity among patients with DSM-IV major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1-3):110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, DeStafano AL, Bis JC, Beecham GW, Grenier-Boley B, Russo G, Thorton-Wells TA, Jones N, Smith AV, Chouraki V, Thomas C, Ikram MA, Zelenika D, Vardarajan BN, Kamatani Y, Lin CF, Gerrish A, Schmidt H, Kunkle B, Dunstan ML, Ruiz A, Bihoreau MT, Choi SH, Reitz C, Pasquier F, Cruchaga C, Craig D, Amin N, Berr C, Lopez OL, De Jager PL, Deramecourt V, Johnston JA, Evans D, Lovestone S, Letenneur L, Moron FJ, Rubinsztein DC, Eiriksdottir G, Sleegers K, Goate AM, Fievet N, Huentelman MW, Gill M, Brown K, Kamboh MI, Keller L, Barberger-Gateau P, McGuiness B, Larson EB, Green R, Myers AJ, Dufouil C, Todd S, Wallon D, Love S, Rogaeva E, Gallacher J, St George-Hyslop P, Clarimon J, Lleo A, Bayer A, Tsuang DW, Yu L, Tsolaki M, Bossu P, Spalletta G, Proitsi P, Collinge J, Sorbi S, Sanchez-Garcia F, Fox NC, Hardy J, Deniz Naranjo MC, Bosco P, Clarke R, Brayne C, Galimberti D, Mancuso M, Matthews F, Moebus S, Mecocci P, Del Zompo M, Maier W, Hampel H, Pilotto A, Bullido M, Panza F, Caffarra P, Nacmias B, Gilbert JR, Mayhaus M, Lannefelt L, Hakonarson H, Pichler S, Carrasquillo MM, Ingelsson M, Beekly D, Alvarez V, Zou F, Valladares O, Younkin SG, Coto E, Hamilton-Nelson KL, Gu W, Razquin C, Pastor P, Mateo I, Owen MJ, Faber KM, Jonsson PV, Combarros O, O'Donovan MC, Cantwell LB, Soininen H, Blacker D, Mead S, Mosley TH, Jr, Bennett DA, Harris TB, Fratiglioni L, Holmes C, de Bruijn RF, Passmore P, Montine TJ, Bettens K, Rotter JI, Brice A, Morgan K, Foroud TM, Kukull WA, Hannequin D, Powell JF, Nalls MA, Ritchie K, Lunetta KL, Kauwe JS, Boerwinkle E, Riemenschneider M, Boada M, Hiltuenen M, Martin ER, Schmidt R, Rujescu D, Wang LS, Dartigues JF, Mayeux R, Tzourio C, Hofman A, Nothen MM, Graff C, Psaty BM, Jones L, Haines JL, Holmans PA, Lathrop M, Pericak-Vance MA, Launer LJ, Farrer LA, van Duijn CM, Van Broeckhoven C, Moskvina V, Seshadri S, Williams J, Schellenberg GD, Amouyel P European Alzheimer's Disease I, Genetic, Environmental Risk in Alzheimer's D, Alzheimer's Disease Genetic C, Cohorts for H, Aging Research in Genomic E. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45(12):1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/ng.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PH, O'Dushlaine C, Thomas B, Purcell SM. INRICH: interval-based enrichment analysis for genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(13):1797–1799. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CA. The behavioral phenotype of Williams syndrome: A recognizable pattern of neurodevelopment. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2010;154C(4):427–431. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otowa T, Hek K, Lee M, Byrne EM, Mirza SS, Nivard MG, Bigdeli T, Aggen SH, Adkins D, Wolen A, Fanous A, Keller MC, Castelao E, Kutalik Z, der Auwera SV, Homuth G, Nauck M, Teumer A, Milaneschi Y, Hottenga JJ, Direk N, Hofman A, Uitterlinden A, Mulder CL, Henders AK, Medland SE, Gordon S, Heath AC, Madden PA, Pergadia ML, van der Most PJ, Nolte IM, van Oort FV, Hartman CA, Oldehinkel AJ, Preisig M, Grabe HJ, Middeldorp CM, Penninx BW, Boomsma D, Martin NG, Montgomery G, Maher BS, van den Oord EJ, Wray NR, Tiemeier H, Hettema JM. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of anxiety disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otowa T, Maher BS, Aggen SH, McClay JL, van den Oord EJ, Hettema JM. Genome-wide and gene-based association studies of anxiety disorders in European and African American samples. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Brown TA, Chiu WT, Sareen J, Stein MB, Kessler RC. Social fears and social phobia in the USA: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2008;38(1):15–28. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaini S, Belotti R, Ogliari A. Genetic and environmental contributions to social anxiety across different ages: a meta-analytic approach to twin data. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(7):650–656. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ, Escott-Price V, Davies G, Bailey ME, Colodro-Conde L, Ward J, Vedernikov A, Marioni R, Cullen B, Lyall D, Hagenaars SP, Liewald DC, Luciano M, Gale CR, Ritchie SJ, Hayward C, Nicholl B, Bulik-Sullivan B, Adams M, Couvy-Duchesne B, Graham N, Mackay D, Evans J, Smith BH, Porteous DJ, Medland SE, Martin NG, Holmans P, McIntosh AM, Pell JP, Deary IJ, O'Donovan MC. Genome-wide analysis of over 106 000 individuals identifies 9 neuroticism-associated loci. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(6):749–757. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoller JW, Paulus MP, Fagerness JA, Purcell S, Yamaki LH, Hirshfeld-Becker D, Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Gelernter J, Stein MB. Influence of RGS2 on anxiety-related temperament, personality, and brain function. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(3):298–308. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Andrews AM. Serotonin States and Social Anxiety. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):845–847. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Chartier MJ, Lizak MV, Jang KL. Familial aggregation of anxiety-related quantitative traits in generalized social phobia: clues to understanding “disorder” heritability? Am J Med Genet. 2001;105(1):79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Chen CY, Ursano RJ, Cai T, Gelernter J, Heeringa SG, Jain S, Jensen KP, Maihofer AX, Mitchell C, Nievergelt CM, Nock MK, Neale BM, Polimanti R, Ripke S, Sun X, Thomas ML, Wang Q, Ware EB, Borja S, Kessler RC, Smoller JW Army Study to Assess R, Resilience in Servicemembers C. Genome-wide Association Studies of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in 2 Cohorts of US Army Soldiers. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(7):695–704. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Gelernter J. Genetic factors in social anxiety disorder In: Weeks JW, editor The Wiley Handbook of Social Anxiety Disorder. Chichester, U.K: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Jang KL, Livesley WJ. Heritability of social anxiety-related concerns and personality characteristics: a twin study. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2002;190(4):219–224. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200204000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Stein DJ. Social anxiety disorder. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz JR, Waller R, Bogdan R, Knodt AR, Sabhlok A, Hyde LW, Hariri AR. A Common Polymorphism in a Williams Syndrome Gene Predicts Amygdala Reactivity and Extraversion in Healthy Adults. Biol Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB Army Sc. The Army study to assess risk and resilience in servicemembers (Army STARRS) Psychiatry. 2014;77(2):107–119. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg SM, de Moor MH, Verweij KJ, Krueger RF, Luciano M, Arias Vasquez A, Matteson LK, Derringer J, Esko T, Amin N, Gordon SD, Hansell NK, Hart AB, Seppala I, Huffman JE, Konte B, Lahti J, Lee M, Miller M, Nutile T, Tanaka T, Teumer A, Viktorin A, Wedenoja J, Abdellaoui A, Abecasis GR, Adkins DE, Agrawal A, Allik J, Appel K, Bigdeli TB, Busonero F, Campbell H, Costa PT, Smith GD, Davies G, de Wit H, Ding J, Engelhardt BE, Eriksson JG, Fedko IO, Ferrucci L, Franke B, Giegling I, Grucza R, Hartmann AM, Heath AC, Heinonen K, Henders AK, Homuth G, Hottenga JJ, Iacono WG, Janzing J, Jokela M, Karlsson R, Kemp JP, Kirkpatrick MG, Latvala A, Lehtimaki T, Liewald DC, Madden PA, Magri C, Magnusson PK, Marten J, Maschio A, Mbarek H, Medland SE, Mihailov E, Milaneschi Y, Montgomery GW, Nauck M, Nivard MG, Ouwens KG, Palotie A, Pettersson E, Polasek O, Qian Y, Pulkki-Raback L, Raitakari OT, Realo A, Rose RJ, Ruggiero D, Schmidt CO, Slutske WS, Sorice R, Starr JM, St Pourcain B, Sutin AR, Timpson NJ, Trochet H, Vermeulen S, Vuoksimaa E, Widen E, Wouda J, Wright MJ, Zgaga L, Generation S, Porteous D, Minelli A, Palmer AA, Rujescu D, Ciullo M, Hayward C, Rudan I, Metspalu A, Kaprio J, Deary IJ, Raikkonen K, Wilson JF, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L, Bierut LJ, Hettema JM, Grabe HJ, Penninx BW, van Duijn CM, Evans DM, Schlessinger D, Pedersen NL, Terracciano A, McGue M, Martin NG, Boomsma DI. Meta-analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies for Extraversion: Findings from the Genetics of Personality Consortium. Behav Genet. 2016;46(2):170–182. doi: 10.1007/s10519-015-9735-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Naragon-Gainey K. Personality, Emotions, and the Emotional Disorders. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2(4):422–442. doi: 10.1177/2167702614536162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Bakshi A, Zhu Z, Hemani G, Vinkhuyzen AA, Lee SH, Robinson MR, Perry JR, Nolte IM, van Vliet-Ostaptchouk JV, Snieder H, LifeLines Cohort S, Esko T, Milani L, Magi R, Metspalu A, Hamsten A, Magnusson PK, Pedersen NL, Ingelsson E, Soranzo N, Keller MC, Wray NR, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. Genetic variance estimation with imputed variants finds negligible missing heritability for human height and body mass index. Nat Genet. 2015;47(10):1114–1120. doi: 10.1038/ng.3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.