Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common form of cancer with prevalence worldwide. There are many factors that lead to the development and progression of HCC. This study aimed to identify potential new tumor suppressors, examine their function as cell cycle modulators, and investigate their impact on the cyclin family of proteins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). In this study, the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK)4 gene was shown to have potential tumor suppressor characteristics. PDK4 expression was significantly downregulated in human HCC. Pdk4−/− mouse liver exhibited a consistent increase in cell cycle regulator proteins, including cyclin D1, cyclin E1, cyclin A2, some associated CDKs, and transcription factor E2F1. PDK4-knockdown HCC cells also progressed faster through the cell cycle, which concurrently expressed high levels of cyclins and E2F1 as seen in the Pdk4−/− mice. Interestingly, the induced cyclin E1 and cyclin A2 caused by Pdk4 deficiency was repressed by arsenic treatment in mouse liver and in HCC cells. E2f1 deficiency in E2f1−/− mouse liver or knockdown E2F1 using small hairpin RNAs in HCC cells significantly decreased cyclin E1, cyclin A2, and E2F1 proteins. In contrast, inhibition of PDK4 activity in HCC cells increased cyclin E1, cyclin A2, and E2F1 proteins. These findings demonstrate that PDK4 is a critical regulator of hepatocyte proliferation via E2F1-mediated regulation of cyclins.

Introduction

Liver cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, with an estimated 745,500 deaths yearly. The majority of liver cancer deaths are identified as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The mechanisms behind HCC progression are continually studied. Many factors that increase the risk of HCC have been identified, including environmental factors, viral infection, alcohol consumption, and smoking (Kanda et al., 2015). Cyclins are vital cell cycle regulators that normally function to ensure the control of cellular proliferation. The cyclin family of proteins and the associated cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) have been shown to be significantly elevated in HCC tissues (Masaki et al., 2003). Identification of cyclin modulators will aid in the understanding of HCC development and progression.

Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase PDK4 is a mitochondrial protein with a histidine kinase domain that inhibits the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC). Inhibition of the PDC results in reduced conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA is used in the citric acid cycle to carry out cellular respiration (Sugden and Holness, 2003). PDK4 is a major factor in cellular respiration, since it works to inhibit the progression from glycolysis to the citric acid cycle. Cellular respiration is a major physiologic factor that was shown to be altered in cancer cells (Scatena, 2012); therefore, PDK4 is a prime molecular suspect in crosstalk between cellular respiration and cell cycle progression. Because liver cells are highly aerobic and metabolically active, liver tissue and associated cells serve as excellent test subjects.

Arsenic is identified as a group 1 carcinogen and is the 20th most common element in the earth’s crust (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2012). Over 100 million people worldwide are exposed to arsenic-contaminated drinking water, making it a global health concern (Polya and Charlet, 2009). Arsenic has been reported to induce epigenetic alterations related to HCC progression (Liu et al., 2014) and to silence hepatic PDK4 expression through activation of histone H3K9 methyltransferase G9a (Zhang et al., 2016).

Nuclear receptors are a class of proteins that mediate the activity of hormones and have been implicated in various diseases, including HCC (Rudraiah et al., 2016). The small heterodimer partner (SHP) is a unique transcriptional repressor (Zhou et al., 2010) and has been implicated as a critical inhibitor of HCC progression (Zhang et al., 2011b) by regulating multiple pathways involved in tumor growth, including cell proliferation (Zhang et al., 2008), apoptosis (Farhana et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2010), and migration and invasion (Yang et al., 2016). Intriguingly, SHP represses DNA methylation via suppressing DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) expression (Zhang and Wang, 2011; Zhang et al., 2012), suggesting that modulating SHP function by its agonist may be useful to develop epigenetic-based therapeutic treatment of HCC.

Using an unbiased approach that included a combination of methylated DNA immunoprecipitation on chromatin immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) methods in Shp−/− mice, this study identified PDK4 as a potential tumor suppressor gene. The expression of PDK4 was markedly reduced in human HCC specimens and in mouse liver tumors. The Pdk4−/− liver had a significant induction in multiple cyclin proteins, with the most striking elevation of cyclin E1, cyclin A2, and E2F1, whereas Pdk4-knockdown HCC cells exhibited a similar activation of cyclin proteins and progressed faster through the G2/M phase of the cell cycle compared with control cells. Interestingly, arsenic decreased the levels of cyclin proteins in both mouse livers and cultured HCC cells that were induced by Pdk4 deficiency. Overall, our study revealed a novel function of PDK4 in cell cycle control, suggesting a critical role of PDK4 in HCC progression.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Study and Treatment.

Wild-type (WT) and Shp−/− mice were described previously (Wang et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2015). Pdk4−/− mice were kindly provided by Dr. Robert Harris (emeritus professor from Indiana University) (Hwang et al., 2009). All mice were of C57BL/6J background, were fed a standard rodent chow with free access to water, and were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on from 6 AM to 6 PM) in a temperature-controlled (23°C) and virus-free facility. Experiments were performed on male mice at the age of 8–12 weeks unless stated otherwise (n = 5 per group). Experimental groups included WT control (WT Con), WT with arsenic exposure (WT As), Pdk4−/− control (Pdk4−/− Con), and Pdk4−/− with arsenic treatment (Pdk4−/− As). For arsenic treatment, mice were fed with 50 ppm NaAsO2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) via distilled drinking water, which was replaced every other day for 4 weeks (Zhang et al., 2016). RNA-seq and MeDIP were conducted at the Microarray and Genomic Analysis Core Facility at the University of Utah (Salt Lake City, UT) as described previously (Smalling et al., 2013). Immunohistochemistry staining was performed on paraffin-embedded liver-section slides with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) antibody (13110; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). ImmPACT DAB peroxidase (SK-4105; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was used for color detection with a hematoxylin counterstain. PCNA staining was conducted on five mice per group with three liver tissue sections per mouse. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to quantify positive PCNA staining. Protocols for animal use were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee at the University of Connecticut.

Liver Specimens.

The coded human liver specimens were obtained through the Liver Tissue Procurement and Distribution System (Minneapolis, MN) and were described previously (He et al., 2008). Because we did not ascertain individual identities associated with the samples, the Institutional Review Board for Human Research at the University of Connecticut determined that the project was not research involving human subjects.

Cell Culture Experiments, Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Analysis, and Luciferase Promoter Assay.

Huh7 (Zhang and Wang, 2011) and 293T (Yang and Wang, 2012) cells were described previously. Cultured cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Mediatech, Manassas, VA). High- and low-efficiency (shPDK4 H and shPDK4 L, respectively) PDK4 knockdown cell lines were generated by a lentiviral vector containing the small hairpin RNA (shRNA) along with packing vector and envelope vector. These components were cotransfected into 293T cells using X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The supernatant containing virus particles was collected and concentrated. Suspended virus was applied to target cells with 6 μg/ml polybrene. The shPDK4H cell line was generated using shRNA (TRCN0000006264, clone ID NM_002612.2-2954s1c) from Sigma-Aldrich, and the shPDK4 L was generated using shRNA (TRCN0000194917, clone ID NM_002612.2-1297s1c1) also from Sigma-Aldrich. shPDK4L cells were treated with 15 µM arsenic for 24 hours. E2F1 shRNAs were from Sigma-Aldrich (shE2F1 1: TRCN0000039659, clone ID NM_005225.1-502s1c1; and shE2F1 2: TRCN0000010328, clone ID NM_005225.x-1171s1c1). The PDK4 inhibitor diisopropylamine dichloroacetate was from Fisher Scientific (cat. no. AAH6134103, Hampton, NH).

Western Blotting, Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction, and Transient Transfection and Luciferase Assay.

Western blotting and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) methods were well established in our laboratory, as described previously (Yang et al., 2013b; Tsuchiya et al., 2015). All antibodies used for Western blotting were as follows: cyclin D1 (Cell Signaling Technology), cyclin E1 (Cell Signaling Technology), cyclin A2 (Cell Signaling Technology), cyclin D3 (Cell Signaling Technology), cyclin H (Cell Signaling Technology), cyclin E2 (Cell Signaling Technology), CDK2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), CDK4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Cell Signaling Technology), p21 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Rb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), pRB (Cell Signaling Technology), MyB (Millipore, Billerica, MA), glycogen synthase kinase-3β (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), SMAD4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and E2F1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All qPCR experiments were repeated three times with each sample run in triplicate. All Western blot experiments were repeated three times. For the mouse study, five mouse samples were pooled per group and the samples were loaded as singlets or duplicates. For the transient transfection and luciferase reporter assay, Huh7 cells were transfected with the plasmids as indicated in the figure legends. Transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Luciferase activity was measured and normalized against Renilla activity (Promega, Madison, WI). Experiments were done in three independent triplicate transfection assays (Yang et al., 2013a).

Statistical Analysis.

Data are shown as means ± S.E.M. Statistical analysis was carried out using the t test for unpaired data to compare the values between the two groups and using one-way analysis of variance to compare the values among multiple groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

An Unbiased Approach to Identify New Tumor Suppressors Using Shp−/− Mice.

In the past decade, our published results using both in vivo mouse and in vitro cell models, as well as human HCC specimens, revealed a tumor-suppressive role of SHP in HCC (He et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008, 2010; Yang et al., 2013b). More recently, our studies established a crucial inhibitory feedback loop between SHP and Dnmt1 (Zhang and Wang, 2011; Zhang et al., 2012). Tumor suppressors are generally downregulated in cancers by DNA hypermethylation via the activity of DNMTs (Jin and Robertson, 2013). We propose that the upregulated Dnmts in Shp−/− mice due to the loss of SHP inhibition will, in turn, methylate other tumor suppressor genes (Fig. 1A). From this regulatory model, we developed an unbiased approach to identify putative new tumor suppressors, as described below.

Fig. 1.

Regulatory model and unbiased approach to identify new tumor suppressor candidates in HCC. (A) A feedback inhibitory loop between Shp and Dnmts. SHP downregulation by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in HCC releases SHP repression of Dnmt and increases Dnmt activity. Upregulated Dnmts further methylate SHP and other tumor suppressor genes. (B) MeDIP arrays. The Mouse Promoter 1.0R Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) is a single array composed of over 4.6 million probes tiled to interrogate over 28,000 mouse promoter regions. (C) RNA-seq. Pol II RNAs were isolated by a 5′-capped purification method and analyzed by RNA-seq. Two-month-old male mice were used for this experiment (n = 5 per group).

Two genome-wide high-throughput analyses were conducted in Shp−/− mice. MeDIP was used to characterize alterations in DNA methylation of specific genes (Fig. 1B) and RNA-seq was used to determine changes in gene expression (Fig. 1C). By integrating both datasets using bioinformatics tools and appropriate validation, we aimed at identifying genes that met the criteria by showing promoter hypermethylation and mRNA downregulation, the characteristics of tumor suppressors, in Shp−/− mice.

Integrating RNA-Seq and MeDIP Revealed PDK4 as a Potential Tumor Suppressor.

Shp−/− mice were originally generated by replacing their exon 1 with the β-gal/pGKneo cassette (Wang et al., 2002). The accuracy of RNA-seq was validated by the missing exon 1 of the Shp gene (Fig. 2A, left, top) and the upregulation of a known SHP target gene, early growth response 1, in Shp−/− mice (Zhang et al., 2011a; Smalling et al., 2013) (Fig. 2A, left, bottom). MeDIP analysis revealed enhanced DNA methylation in the Shp gene promoter in Shp−/− mice (Fig. 2A, right), further supporting our proposed feedback regulatory loop between SHP and Dnmts (Fig. 1A). We integrated MeDIP and RNA-seq data and identified the top 10 genes that showed hypermethylation and downregulation in Shp−/− mice (Fig. 2B). We chose to focus on the PDK4 gene due to its striking hypermethylated promoter and downregulated expression in Shp−/− mice (Fig. 2C). In agreement with the RNA-seq results, qPCR confirmed a marked reduction of Pdk4 mRNA in Shp−/− livers that were collected from both young and old mice (aged 2 and 13 months, respectively) (Fig. 2D). Pdk4 mRNA levels were also consistently low in Shp−/− mouse tumor tissue (Shp−/−-T).

Fig. 2.

Integrating MeDIP and RNA-seq results identified PDK4 as a putative tumor suppressor in HCC. (A) (Left) Integrated Genome Browser visualization tracks from RNA-seq reads depict complete loss of Shp exon 1 in Shp−/− mice. Early growth response 1 (Egr-1), a known target of Shp, is increased 8-fold in Shp−/− versus WT livers. (Right) Enhanced DNA methylation signal (blue lines) in the Shp gene promoter in Shp−/− versus WT mice. (B) Genes showed good correlation between promoter methylation and gene expression in Shp−/− mice and Pdk4 was among the top 10 genes. (C) MeDIP and RNA-seq revealed Pdk4 promoter hypermethylation and gene downregulation in Shp−/− livers. (D) qPCR of Pdk4 mRNA in 2- and 13-month-old WT, Shp−/−, and Shp−/−-T (tumor) livers (n = 5 per group). (E) qPCR of PDK4 mRNA in 21 pairs of human HCC specimens and the corresponding controls. (F) qPCR of PDK4 mRNA in HCC cells treated with Aza or trichostatin. (G) (Left) The methylated DNA levels of the PDK4 promoter CpG island were quantified using the EpiTect methyl-profiler qPCR primer assay (QIAGEN). (Right) qPCR of PDK4 mRNA. In the bar graphs, data are shown as means ± S.E.M. (triplicate assays). *P < 0.05 versus corresponding controls. DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; TSA, trichostatin.

Importantly, PDK4 mRNA was significantly diminished in human HCC specimens relative to surrounding liver tissue (Fig. 2E), suggesting that a low level of PDK4 is associated with the development of HCC. Analysis of the Oncomine database revealed an overall diminished expression of PDK4 in a variety of human cancers (Supplemental Fig. 1). It should be noted that other PDK isoenzymes (PDK1–PDK3) did not show such universal downregulation (not shown), suggesting a specific regulatory role of PDK4 in HCC and other cancers.

Treatment of multiple HCC cell lines with the demethylating agent 5′-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Aza) or histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin revealed an induction of PDK4 mRNA in Hep3B and HepG2 cells by Aza and in Hep3B, MH97H, and MH97L cells by TSA (Fig. 2F). In addition, Aza decreased PDK4 gene promoter methylation in HepG2 cells (Fig. 2G, left), which was in agreement with the increased PDK4 mRNA (Fig. 2G, right). Overall, the results suggest that PDK4 downregulation in HCC is associated with epigenetic silencing.

Arsenic Repressed Hepatocyte Proliferation Induced by Pdk4 Deficiency.

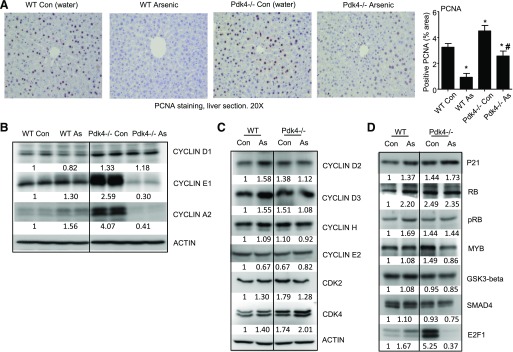

To examine the in vivo effect of Pdk4 in hepatocyte proliferation and the impact of arsenic, WT and Pdk4−/− mice were fed with arsenic for 2 weeks. Immunohistochemistry staining for the PCNA protein in arsenic-treated and untreated mice showed that Pdk4−/− mice exhibited greater hepatocyte proliferation compared with WT control mice. The liver sections of arsenic-treated mice showed decreased PCNA staining compared with clean water–treated control mice in both WT and Pdk4−/− animals (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Pdk4−/− livers showed increased hepatocyte proliferation, which was diminished by arsenic treatment. (A) (Left) Immunohistochemistry staining for PCNA protein. Dark brown indicates positively stained nuclei. (Right) Histogram showing quantification of positive PCNA staining results. *P < 0.05 versus WT Con; #P < 0.05 versus Pdk4−/− Con. (B–D) Western blot of cyclin and CDK proteins and cell cycle modulators in WT and Pdk4−/− mice treated with arsenic (50 ppm for 1 month). Pooled samples (n = 5 per group) were run in duplicate lanes or single lane. Numbers indicate density relative to WT control (Con).

To further investigate the molecular components responsible for the cell proliferation changes among test groups, cell cycle proteins were analyzed via Western blotting. We first examined three major cyclins and observed that Pdk4−/− control livers had a drastic increase in cyclin E1 and A2 proteins compared with that of WT control livers (Fig. 3B). In contrast, arsenic treatment prevented the induction of cyclin E1 and A2 proteins in Pdk4−/− As mice compared with Pdk4−/− Con mice (Fig. 3B).

We continued to analyze other cell cycle regulatory proteins by Western blotting to gain a better understanding of the overall changes. Interestingly, cyclin D2 and D3 levels were moderately increased in WT As versus WT Con mice (Fig. 3C). On the other hand, CDK2 and CDK4 were noticeably elevated in Pdk4−/− mice relative to WT mice. Among other cell cycle regulators we analyzed, transcription factor E2F1 protein was found to be highly induced in Pdk4−/− Con mice compared with WT Con mice, and its induction was prevented by arsenic treatment (Fig. 3D). Because E2F1 is a well established transcriptional activator of cyclins (Wu et al., 2001), the similar expression pattern between E2F1 and cyclins E1 and A2 in Pdk4−/− mice suggests that E2F1 may be responsible for the upregulation of both cyclins.

Knockdown of PDK4 Expedited HCC Cell Progression.

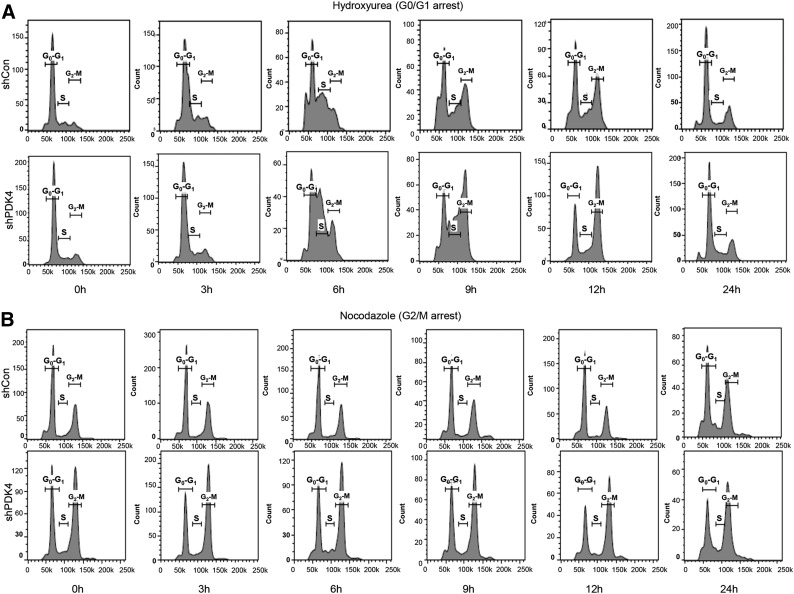

We next examined the effect of PDK4 in HCC cell proliferation using in vitro cell models. Huh7 cells were treated with hydroxyurea to synchronize all cells at the G0/G1 phase (Fig. 4A). When PDK4-knockdown (shPDK4) cells were released into the cell cycle, they progressed faster through all phases of the cell cycle. At 6 hours, shPDK4 cells had a higher percentage in the S phase compared with shControl cells. By the 9-hour and 12-hour time points, shPDK4 cells showed a greater transition to the G2/M phase compared with shCon cells.

Fig. 4.

FACS analysis showed rapid G2/M cell cycle progression in shPDK4 HCC cells. (A) shCTRL and shPDK4 cells synchronized in G1/S phase by hydroxyurea treatment (3 mM for 24 hours) followed by FACS. (B) shCTRL and shPDK4 cells synchronized in the G2/M phase by nocodazole (50 ng/ml for 16 hours) treatment followed by FACS. FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Nocodazole was used to arrest Huh7 cells in the G2/M phase, where a higher percentage of shPDK4 cells accumulated in the G2/M phase compared with shCon cells (Fig. 4A). As time progressed, shPDK4 cells appeared to maintain a constant high percentage of G2/M cells compared with shCon cells (Fig. 4B).

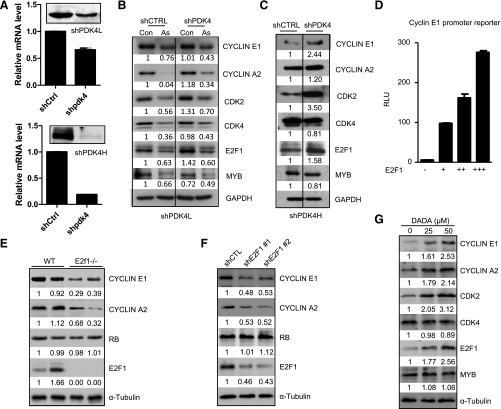

Because cyclins E1 and A2 were the two most highly induced cyclins in Pdk4−/− liver (Fig. 3B), we examined their protein expression in PDK4-knockdown Huh7 cells. Two knockdown cell lines were established with moderate (Fig. 5A, top) to strong knockdown efficiency (Fig. 5A, bottom). In cells with moderate Pdk4 knockdown, small increases in cyclin A2, CDK2, and E2F1 were observed (Fig. 5B). In high Pdk4-knockdown cells, a more striking elevation of cyclin E1, CDK2, and E2F1 was observed (Fig. 5C). Therefore, the more efficient knockdown of PDK4 resulted in greater induction of cell cycle regulator proteins. As expected, E2F1 dose-dependently transactivated cyclin E1 promoter activity (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Knockdown of PDK4 in HCC cells induced cell cycle proteins, which was diminished by arsenic. (A) Western blot of PDK4 protein and qPCR of PDK4 mRNA in Huh7 cells showing lower (top) and higher (bottom) knockdown efficiency (shPDK4L). (B) Western blot of cell cycle proteins in control (shCTRL) or shPDK4L cells in the presence or absence of arsenic (As) (15 μM for 24 hours). (C) Western blot of cell cycle proteins in shCTRL and shPDK4H cells. (D) Transient transfection assay to determine cyclin E1 promoter reporter activity by E2F1. (E) Western blot of protein expression in WT and E2f1−/− mouse liver. (F) Western blot of protein expression in Huh7 cells with E2F1 knockdown using two different shRNAs against E2F1. (G) Western blot of protein expression in Huh7 cells treated with PDK4 inhibitor diisopropylamine dichloroacetate (DADA).

The levels of cyclin E1 and A2 proteins were markedly diminished in E2f1−/− mouse liver compared with WT mice (Fig. 5E). In addition, knockdown of E2F1 using shRNAs in Huh7 cells significantly decreased cyclin E1, cyclin A2, and E2F1 proteins (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, treatment of Huh7 cells with PDK4 inhibitor diisopropylamine dichloroacetate increased cyclin E1, cyclin A2, and E2F1 proteins dose dependently (Fig. 5G). Taken together, the results suggest an E2F1-dependent activation of cyclins E1 and A2 by PDK4.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify potential new tumor suppressor genes using Shp−/− mice, based on our previous findings that established a feedback regulatory loop between DNMTs and SHP (Zhang and Wang, 2011; Zhang et al., 2012). Tumor suppressors are often downregulated in cancers due to their promoter hypermethylation. PDK4 was identified as a putative tumor suppressor because its expression was largely diminished in human HCC specimens and other cancers.

One prime characteristic of tumor suppressor genes is their ability to inhibit tumor cell growth. Thus, we examined the role of PDK4 in hepatic cell proliferation. Consistent with our hypothesis, Pdk4-deficient mouse liver showed increased hepatocyte proliferation, as evidenced by the activation and induction of cyclins. In addition, HCC cells with PDK4 knockdown exhibited a similar activation of cell cycle regulators, which was accompanied by enhanced cell cycle progression. It was noted that results in HCC cells were less striking than in mouse livers, which was likely caused by the different cellular environment in HCC cells versus mouse livers. Overall, these results strongly suggest PDK4 as an important new regulator of the cell cycle.

To date, very little research has been done analyzing PDK4 outside of its known metabolic function. The Warburg effect suggests that cancer cells rely highly on glycolysis rather than oxidative phosphorylation (Liberti and Locasale, 2016). Since PDK4 functions to inhibit PDC, which converts pyruvate into acetyl-CoA and therefore feeds the citric acid cycle, PDK4 is expected to interact with other proteins leading to the subsequent inhibition in cellular proliferation. Because the levels of multiple cyclins were highly induced by PDK4 deficiency, it is postulated that PDK4 may repress the expression of cyclins via interaction with other transcription factors. E2F1 is a major transcriptional activator of cyclins that we observed to be strongly induced in Pdk4−/− liver and PDK4-knockdown HCC cells. Therefore, we examined a direct protein-protein interaction between PDK4 and E2F1 by coimmunoprecipitation and Western blotting but failed to validate their interaction (not shown). As expected, E2F1 dose-dependently activated cyclin E1 promoter activity (Fig. 5E). Unfortunately, coexpression of PDK4 with E2F1 did not alter E2F1 transactivation (not shown). These results suggest that PDK4, a mitochondria protein, does not seem to act as a transcriptional factor to enhance E2F1 activity. It is likely that there are intermediate players between PDK4 and E2F1. Future studies may focus on identifying the molecular intermediates leading to increased levels of cyclin E1 caused by Pdk4 deficiency.

In this study, arsenic was found to decrease cyclin protein levels in both mouse and cultured HCC cells. This decrease in cyclin protein levels indicates a reduction in cellular proliferation. Previous studies have shown in different model organisms that inorganic arsenic treatment inhibits cell cycle progression and induces apoptosis (Sidhu et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007). Our results were in agreement with the prior observations. The inhibitory effect of arsenic in HCC cell proliferation is in contrast with the general knowledge that arsenic is often considered to have oncogenic properties by predisposed cells for cancer development. We also noted that despite reduced hepatocyte proliferation by arsenic treatment, the overall cyclin levels were not decreased. Future studies are warranted to fully understand the action of arsenic. The results suggest that the final outcome of arsenic exposure would be largely depending on the cellular context.

In summary, this study shows that Pdk4 deficiency results in increased hepatocyte proliferation as a consequence of induction of cyclins and E2F1. These results suggest that PDK4 may function as a potential tumor suppressor. Unfortunately, we are unable to establish an in vivo HCC model, because Pdk4−/− mice injected with a single dose of diethylnitrosamine died within a week. We are currently investigating the molecular mechanisms that may explain the causes of death. Nonetheless, identification of tumor suppressor genes and their molecular mechanisms will and has led to therapies and anticancer treatments. Future studies may focus on further elucidating the molecular pathway in which Pdk4 deficiency increases the level of cyclin proteins, as well as the effects of arsenic and Pdk4 on apoptosis in the liver.

Abbreviations

- Aza

5′-aza-2′-deoxycytidine

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferase

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- MeDIP

methylated DNA immunoprecipitation on chromatin immunoprecipitation

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PDC

pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

- PDK

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- SHP

small heterodimer partner

- shRNA

small hairpin RNA

- WT

wild type

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Choiniere, Wu, Wang.

Conducted experiments: Choiniere, Wu.

Performed data analysis: Choiniere, Wang.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Choiniere, Wang.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Grant R01-ES025909], the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [R01-DK080440, R01-DK104656, and P30-DK34989 (to Yale Liver Center)], the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [Grants R21-AA022482 and R21-AA024935], and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs [Merit Award 1I01BX002634].

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Farhana L, Dawson MI, Leid M, Wang L, Moore DD, Liu G, Xia Z, Fontana JA. (2007) Adamantyl-substituted retinoid-related molecules bind small heterodimer partner and modulate the Sin3A repressor. Cancer Res 67:318–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He N, Park K, Zhang Y, Huang J, Lu S, Wang L. (2008) Epigenetic inhibition of nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner is associated with and regulates hepatocellular carcinoma growth. Gastroenterology 134:793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang B, Jeoung NH, Harris RA. (2009) Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoenzyme 4 (PDHK4) deficiency attenuates the long-term negative effects of a high-saturated fat diet. Biochem J 423:243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (2012). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans—Arsenic, Metals, Fibres, and Dusts: A Review of Human Carcinogens, vol 100C. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin B, Robertson KD. (2013) DNA methyltransferases, DNA damage repair, and cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 754:3–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda M, Sugimoto H, Kodera Y. (2015) Genetic and epigenetic aspects of initiation and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 21:10584–10597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Zhang Y, Tsuchiya H, Smalling R, Jetten AM, Wang L. (2015) Small heterodimer partner/neuronal PAS domain protein 2 axis regulates the oscillation of liver lipid metabolism. Hepatology 61:497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberti MV, Locasale JW. (2016) The Warburg effect: how does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem Sci 41:211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Jiang L, Guan XY. (2014) The genetic and epigenetic alterations in human hepatocellular carcinoma: a recent update. Protein Cell 5:673–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki T, Shiratori Y, Rengifo W, Igarashi K, Yamagata M, Kurokohchi K, Uchida N, Miyauchi Y, Yoshiji H, Watanabe S, et al. (2003) Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases: comparative study of hepatocellular carcinoma versus cirrhosis. Hepatology 37:534–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polya D, Charlet L. (2009) Environmental science: rising arsenic risk? Nat Geosci 2:383–384. [Google Scholar]

- Rudraiah S, Zhang X, Wang L. (2016) Nuclear receptors as therapeutic targets in liver disease: are we there yet? Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 56:605–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scatena R. (2012) Mitochondria and cancer: a growing role in apoptosis, cancer cell metabolism and dedifferentiation. Adv Exp Med Biol 942:287–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu JS, Ponce RA, Vredevoogd MA, Yu X, Gribble E, Hong SW, Schneider E, and Faustman EM (2006) Cell cycle inhibition by sodium arsenite in primary embryonic rat midbrain neuroepithelial cells. Toxicol Sci 89:475–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalling RL, Delker DA, Zhang Y, Nieto N, McGuiness MS, Liu S, Friedman SL, Hagedorn CH, Wang L. (2013) Genome-wide transcriptome analysis identifies novel gene signatures implicated in human chronic liver disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 305:G364–G374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden MC, Holness MJ. (2003) Recent advances in mechanisms regulating glucose oxidation at the level of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex by PDKs. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284:E855–E862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya H, da Costa KA, Lee S, Renga B, Jaeschke H, Yang Z, Orena SJ, Goedken MJ, Zhang Y, Kong B, et al. (2015) Interactions between nuclear receptor SHP and FOXA1 maintain oscillatory homocysteine homeostasis in mice. Gastroenterology 148:1012–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Han Y, Kim CS, Lee YK, Moore DD. (2003) Resistance of SHP-null mice to bile acid-induced liver damage. J Biol Chem 278:44475–44481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Lee YK, Bundman D, Han Y, Thevananther S, Kim CS, Chua SS, Wei P, Heyman RA, Karin M, et al. (2002) Redundant pathways for negative feedback regulation of bile acid production. Dev Cell 2:721–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Zhao Y, Wu L, Tang M, Su C, Hei TK, Yu Z. (2007) Induction of germline cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by sodium arsenite in Caenorhabditis elegans. Chem Res Toxicol 20:181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Timmers C, Maiti B, Saavedra HI, Sang L, Chong GT, Nuckolls F, Giangrande P, Wright FA, Field SJ, et al. (2001) The E2F1-3 transcription factors are essential for cellular proliferation. Nature 414:457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Koehler AN, Wang L. (2016) A novel small molecule activator of nuclear receptor SHP inhibits HCC cell migration via suppressing Ccl2. Mol Cancer Ther 15:2294–2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Tsuchiya H, Zhang Y, Hartnett ME, Wang L. (2013a) MicroRNA-433 inhibits liver cancer cell migration by repressing the protein expression and function of cAMP response element-binding protein. J Biol Chem 288:28893–28899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Wang L. (2012) An autoregulatory feedback loop between Mdm2 and SHP that fine tunes Mdm2 and SHP stability. FEBS Lett 586:1135–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Zhang Y, Wang L. (2013b) A feedback inhibition between miRNA-127 and TGFβ/c-Jun cascade in HCC cell migration via MMP13. PLoS One 8:e65256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wu J, Choiniere J, Yang Z, Huang Y, Bennett J, Wang L. (2016) Arsenic silences hepatic PDK4 expression through activation of histone H3K9 methylatransferase G9a. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 304:42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Andrews GK, Wang L. (2012) Zinc-induced Dnmt1 expression involves antagonism between MTF-1 and nuclear receptor SHP. Nucleic Acids Res 40:4850–4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Bonzo JA, Gonzalez FJ, Wang L. (2011a) Diurnal regulation of the early growth response 1 (Egr-1) protein expression by hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha (HNF4alpha) and small heterodimer partner (SHP) cross-talk in liver fibrosis. J Biol Chem 286:29635–29643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Hagedorn CH, Wang L. (2011b) Role of nuclear receptor SHP in metabolism and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812:893–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Soto J, Park K, Viswanath G, Kuwada S, Abel ED, Wang L. (2010) Nuclear receptor SHP, a death receptor that targets mitochondria, induces apoptosis and inhibits tumor growth. Mol Cell Biol 30:1341–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wang L. (2011) Nuclear receptor SHP inhibition of Dnmt1 expression via ERRγ. FEBS Lett 585:1269–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Xu P, Park K, Choi Y, Moore DD, Wang L. (2008) Orphan receptor small heterodimer partner suppresses tumorigenesis by modulating cyclin D1 expression and cellular proliferation. Hepatology 48:289–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Zhang Y, Macchiarulo A, Yang Z, Cellanetti M, Coto E, Xu P, Pellicciari R, Wang L. (2010) Novel polymorphisms of nuclear receptor SHP associated with functional and structural changes. J Biol Chem 285:24871–24881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]