Abstract

Background

As a legal drug, alcohol is commonly abused and it is estimated that 17 million adults in the United States suffer from alcohol use disorder. Heavy alcoholics can experience withdrawal symptoms including anxiety and mechanical allodynia that can facilitate relapse. The molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are not well understood, which stifles development of new therapeutics. Here we investigate whether delta opioid receptors (DORs) play an active role in alcohol withdrawal-induced mechanical allodynia (AWiMA) and if DOR agonists may provide analgesic relief from AWiMA.

Methods

To study AWiMA, adult male wild-type and DOR knockout C57BL/6 mice were exposed to alcohol by a voluntary drinking model or oral gavage exposure model, which we developed and validated here. We also used the DOR-selective agonist TAN-67 and antagonist naltrindole to examine the involvement of DORs in AWiMA, which was measured using a von Frey model of mechanical allodynia.

Results

We created a robust model of alcohol withdrawal-induced anxiety and mechanical allodynia by orally gavaging mice with 3 g/kg alcohol for three weeks. AWiMA was exacerbated and prolonged in DOR knockout mice as well as by pharmacological blockade of DORs compared to control mice. However, analgesia induced by TAN-67 was attenuated during withdrawal in alcohol-gavaged mice.

Conclusions

DORs appear to play a protective role in the establishment of AWiMA. Our current results indicate that DORs could be targeted to prevent or reduce the development of AWiMA during alcohol use; however, DORs may be a less suitable target to treat AWiMA during active withdrawal.

Keywords: delta opioid receptor, alcohol use disorder, withdrawal, allodynia, hyperalgesia, G protein-coupled receptor

Graphical abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) poses significant health, social and economic burdens on individuals and society. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), in 2013, about 17 million or 7.2 percent of Americans reportedly had an AUD (SAMHSA, 2013). Chronic alcohol exposure can cause neuronal degeneration in the peripheral and central nervous systems (Egli et al., 2012; Mellion et al., 2011; Obernier et al., 2002) resulting in painful small fiber peripheral neuropathy (Dina et al., 2006; Edwards et al., 2012). The hallmarks of neuropathic pain are allodynia (pain responses to normally innocuous stimuli) and hyperalgesia (a heightened reponses to noxious stimuli). Self-medication with alcohol for pain relief is not uncommon and is associated with a drinking problem (Brennan et al., 2005; Riley and King, 2009). Preclinical studies have indicated that alcohol administration can reverse hyperalgesia during alcohol withdrawal in rodents (Gatch and Lal, 1999), but alcohol withdrawal can make the symptoms of small fiber neuropathy worse (Dina et al., 2000; Jochum et al., 2010; Shumilla et al., 2005). These observations are consistent with clinical studies showing exacerbated peripheral neuropathy in alcohol withdrawal patients (Spahn et al., 1995; Yokoyama et al., 1991). Chronic pain can dysregulate overlapping neural substrates of negative emotional states of alcohol addiction such as anxiety and depression (Gilpin and Koob, 2008; Koob, 2003) as well as the craving stage of the addiction cycle (Edwards and Koob, 2010; Egli et al., 2012). The combination of cravings, increased pain and anxiety during periods of alcohol abstinence is known as the ‘alcohol withdrawal syndrome’ and is a negative factor contributing to alcohol relapse (Becker, 2008). Currently, the available drug treatments for AUD rarely combat the complexities of the withdrawal syndrome (Anton et al., 2006; Garbutt, 2009; Garbutt et al., 1999). The mechanisms underlying alcohol withdrawal symptoms especially allodynia are still not well understood, limiting the development of novel treatments for AUD that counter multiple components of the alcohol withdrwawal syndrome.

Protein kinase Cε (PKCε), an intracellular protein kinase, is associated with the alcoholic neuropathy and mechanical hyperalgesia (Dina et al., 2000, 2006; Joseph and Levine, 2010; Shumilla et al., 2005). However, it is difficult to develop truly PKC isoform-selective inhibitors (Roffey et al., 2009). The delta opioid receptor (DOR), which is a membrane localized G protein-coupled receptor, has been shown to produce analgesia and interact with PKCε (Schuster et al., 2013, 2015). DORs are primarily expressed in mechanical pain sensing neurons (Scherrer et al., 2009; van Rijn et al., 2012) and play a crucial role in touch and mechanical sensation (Bardoni et al., 2014; Scherrer et al., 2009), making it a promising target to treat withdrawal hyperalgesia that is generally associated with increased tactile sensation. Moreover, alcohol exposure can elevate functional DOR expression in different areas of the central nervous system (Bie et al., 2009; Margolis et al., 2008; van Rijn et al., 2012). We, therefore, propose that DORs could be a novel target for alcohol withdrawal-induced mechanical allodynia (AWiMA) therapy, particularly considering that DOR agonists also reduce alcohol consumption (van Rijn and Whistler, 2009) and attenuate anxiety-like behaviors in alcohol-withdrawn mice (van Rijn et al., 2010). To investigate our hypothesis, we induced AWiMA by exposing mice to voluntary or forced alcohol for three weeks. We used transgenic DOR knockout (KO) mice as well as the DOR-selective agonist TAN-67 (Nagase et al., 1998) and antagonist naltrindole (Portoghese et al., 1988) to study the role of DORs in AWiMA. Our results obtained with the KO mice and DOR-selective drugs indicate that DORs play an active role in AWiMA, specifically during the alcohol exposure phase.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1 Animals

Adult (8-10 week old) wild-type (WT) or DOR KO C57BL/6 mice (male, 18-23 g, Taconic) were housed (maximally 5 per cage) in ventilated plexiglass cages at ambient temperature (21ºC) in a room maintained on a reversed 12L:12D cycle (lights off at 9:00 AM, lights on at 9:00 PM). DOR KO mice were produced by removal of exon 2 as previously described (van Rijn and Whistler, 2009) and outbred to a C57BL/6 background (>10 generations). Knockout mice were crossbred with WT mice every 3-4 generations to prevent genetic drift. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Purchased mice were given 1.5 week to acclimatize before the start of the experiments. All animal procedures were performed in an AAALAC accredited facility and pre-approved by the Purdue Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2 Chronic voluntary alcohol consumption

A two-bottle limited access (4 hours/day, 5 days/week) drinking paradigm was employed for three weeks to train mice to increase their intake of a 10% alcohol solution as previously described (Rhodes et al., 2005; van Rijn and Whistler, 2009). The first dose of TAN-67 was injected four days after the last alcohol exposure to ensure that no alcohol was left in the mouse’s circulation, and mice returned to a stable nociceptive baseline.

2.3 Administration of alcohol by gavage

Mice received 2 or 3 g/kg of 20% (vol/vol) alcohol in water via oral gavage (o.g.) for five consecutive days each week for three weeks. The first dose of TAN-67 was injected two days after the last alcohol exposure.

2.4 Measurement of mechanical sensitivity

One day prior to testing, mice were placed in plexiglass chambers on a suspended wire mesh grid (25 cm above a table) for one hour for habituation. In these chambers mice were confined but free to move and could turn 360°. On the test day, mice were placed in the chambers one hour before measurement of mechanical sensitivity. Mechanical sensitivity was measured as previously described (van Rijn et al., 2012) by stimulating the plantar surface of the hind paw of the mouse with von Frey filaments (0.04, 0.07, 0.16, 0.4, 0.6, 1, 1.4, 2 g) three times for two seconds at a time. A paw withdrawal at 2 g was considered the maximal response. The 0.4 g filament was always used first and depending on the response either a smaller or bigger filament was tested. The lowest force that evoked a paw withdrawal response in two out of three tests was recorded. Both paws were measured and the average was used for each animal. Data is normalized to the mechanical sensitivity response in naïve/water-treated mice.

2.5 Intrathecal injection

Mice were anaesthetized with 5% isoflurane five minutes prior to injection. Intrathecal (i.t.) injection of opioid solutions (5 or 10 μl) was performed as previously described (Hylden and Wilcox, 1980; van Rijn et al., 2012) by direct puncture of spinal lumbar region (L4-L6) using a luer-tipped 250 μl Hamilton (725LT) syringe to which a 28.5 gauge needle was attached. Upon correct placement of the needle a clear tailflick response could be observed. Drug response was measured ten minutes after i.t. injection. Mice would generally wake up from anesthesia 2-3 minutes after injections and would be fully awake, mobile and responsive upon time of von Frey mechanical sensitiviy measurement. Prior to injection a baseline of von Frey mechanical sensitivity measurement was performed. Data is represented as the percentage maximal possible effect (MPE) which is defined as [(measurement − baseline)/(cutoff − baseline)]*100.

2.6 Drugs and solutions

Alcohol solutions were prepared in tap water using 100% (vol/vol) alcohol (200 proof, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Clonidine, TAN-67 and naltrindole were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). All compounds were dissolved in saline; therefore, we used saline as vehicle in all of our experiments to allow comparison across all treatment groups. All drugs were prepared immediately prior to injection and were administered intrathecally except for natrindole that mice received subcutaneously.

2.7 Alcohol withdrawal-induced anxiety

To study alcohol withdrawal-induced anxiety-like behaviors, mice were orally gavaged with 3 g/kg alcohol for five consecutive days each week for three weeks. Twenty-four hours after the last alcohol exposure anxiety levels in the withdrawn mice were tested by using the open field exploration test and the light-dark transition test by measuring the general locomotor activity.

2.8 Anxiety-like behavior measurements

2.8.1 Open field exploration test

Spontaneous activity was analyzed using automated activity chambers with 48 channel I/R controller (27.3 cm × 27.3 cm × 20.3 cm, WxLxH; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). Boxes were evenly illuminated with 31.4 lux using a shadow-free illumination system. Home cages were brought to the testing room 30 min prior to testing. Each mouse was placed in the center of a chamber. Mice location was tracked for 5 minutes. Time, distance and entries into the center of the open field box were recorded. A decrease in the amount of time spent in the center as well as the number of entries in the center area demonstrate anxiety-like behaviors. Mice were allowed to freely explore the chamber for an additional 55 minute, and their horizontal locomotor activity (total distance traveled) was recorded using a photobeam-based tracking system. The chamber was cleaned with isoproponol and dried before the next mouse was tested. A decrease in locomotor activity may indicate a general sense of malaise.

2.8.2 Light-dark transition test

The light-dark apparatus was made up of an automated activity monitor with a dark box insert (ENV-510; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) to create an equally spaced light and dark compartment (13.6 cm × 27.3 cm × 20.3 cm, WxLxH). The entire apparatus was positioned in a sound-attenuating chamber. The light side was illuminated to a degree of ~60 lux (100mA bulbs – SG-700A), compared with ~5 lux in the dark side. Each animal was placed facing the entrance of the dark area. Mice were allowed to freely explore the chamber for 5 min. The light-dark transition box was cleaned with isopropanol and dried before the next mouse was tested. A photobeam-based tracking system was used to track the movement and locomotor activity of the mice within the test box and calculate the time spent in each area and the number of entries into each area. Anxiety-like effects were indicated by increased time spent in the dark compartment.

2.9 Statistical data analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. The analysis of pharmacological drug effects over time was performed using one-way or two-way, repeated measures ANOVA for drug treatment and genotype, followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test to determine statistically significant differnces between groups using GraphPad Prism5 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Student’s unpaired t-test was used for analyzing less than two groups using GraphPad Prism5. A level of proability of p < 0.05 was deemed to constitute the threshold for statistical significance and marked with an asterisk. For transparency, results with a level of proability of p < 0.01 were marked with **, p < 0.001 with ***.

3. RESULTS

3.1 DORs are protective against allodynia during withdrawal from voluntary moderate alcohol intake

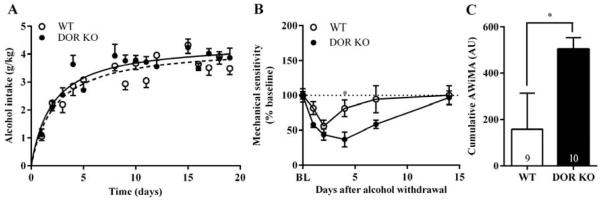

Wild-type and DOR KO C57BL/6 male mice were trained to consume a 10% alcohol solution for three weeks using a limited access (4 hours/day) two-bottle choice drinking in the dark paradigm of voluntary self administration. Wild-type and DOR KO C57BL/6 mice showed similar escalation of voluntary consumption of alcohol (Figure 1A). We found that the two genotypes rapidly developed AWiMA upon termination of alcohol access, as measured by their hind paw withdrawal responses to noxious mechanical pressure using von Frey filaments (Figure 1B). Data was normalized to the von Frey response obtained in mice prior to alcohol exposure (Supplementary Figure 11). Analysis by two-way ANOVA revealed that DOR KO mice exhibited more prolonged and exacerbated AWiMA than WT mice (significant main effect of genotype: F1,17 = 5.505, p < 0.05 and time: F5,85 = 10.24, p < 0.001; Supplementary Figure 12), and this was reflected in the cumulative AWiMA data (measured as (100 – area under the mechanical sensitivity curve)day; Figure 1C). The cumulative AWiMA was significantly higher in DOR KO than in WT mice (p < 0.05).

Figure 1. Endogenous activity at delta opioid receptors attenuate alcohol withdrawal-induced mechanical allodynia in a model of voluntary alcohol consumption.

Wild-type (WT) or DOR knockout (KO) C57BL/6 mice were trained to drink in a limited-access, two-bottle choice paradigm for three weeks, and consumption of the 10% alcohol solution was measured over a 4-h period (A). The mechanical sensitivity measured by using von Frey filaments was assessed on days 1, 2, 4, 7 and 14 after alcohol withdrawal. Significance between groups was determined by two-way ANOVA (B). The cumulative alcohol withdrawal-induced mechanical allodynia (AWiMA) (expressed in arbitrary units (AU)) in WT and DOR KO mice was calculated using the trapezoidal rule (C). *p < .05 normalized versus day 0 (BL, baseline).

3.2 Robust model of alcohol withdrawal using orally gavaged alcohol administration

We next examined whether a more binge-like exposure to alcohol using orally gavaged bolus injections would produce stronger AWiMA and withdrawal syndrome. Wild-type C57BL/6 male mice were orally gavaged with water or 20% vol/vol alcohol solution at 2 g or 3 g alcohol per kg of body weight once a day for three weeks. AWiMA was measured at multiple time points (Figure 2A). We found that there was a significantly greater decrease in mechanical threshold in mice exposed to 3 g/kg alcohol compared to those treated with 2 g/kg alcohol (significant main effect of alcohol concentration: F1,20 = 8.655, p < 0.01; Figure 2B). This was also illustrated by the cumulative AWiMA (p < 0.01) in Figure 2C. Data was normalized to the von Frey response obtained in tap water-treated mice, which did not develop mechanical allodynia (See Supplementary Figure 2 and 33). We next intrathecally injected mice with 10 nmol/10 μl clondine, a medication commonly used for treatment of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. We found that clonidine reduced AWiMA in mice withdrawn for 24 hours from 15 sessions (three weeks) of 3 g/kg o.g. alcohol exposure (F2,27 = 21.81, p < 0.001; Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Mice daily gavaged with 3 g/kg alcohol develop induced mechanical allodynia during alcohol withdrawal.

Timeline for chronic alcohol consumption and measurement of mechanical nociception of Figure 2B and 2D (A). Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were given either 20% alcohol solution (2 g/kg or 3 g/kg) or water via oral gavage (o.g.) once daily for five consecutive days for a duration of three weeks, and mechanical sensitivity was measured using von Frey filaments. Significance between groups was determined by two-way ANOVA (B). The cumulative alcohol withdrawal-induced mechanical allodynia (AWiMA) (expressed in arbitrary units (AU)) in 2 and 3 g/kg gavaged alcohol mice was calculated using the trapezoidal rule (C). 3 g/kg alcohol-withdrawn mice (24 hours after last exposure) were injected intrathecally (i.t.) with 10 nmol/10 ul of α2A-adrenergic receptor agonist clonidine, a medication used for treatment of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. Ten minutes after injection, mechanical antinociception was measured by using von Frey filaments. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA (D). ***p < .001; **p < .01 normalized versus water-treated group.

3.3 Mice withdrawn from gavaged alcohol elicit signs of anxiety and malaise

To investigate the physiological and translational relevance of the o.g. model in more detail, we examined whether mice exposed to gavaged alcohol intake would display other signs of withdrawal. We found that WT C57BL/6 mice exposed to 3 g/kg alcohol for three weeks showed an anxiogenic phenotype 24 hours in withdrawal, as measured by their behaviors in an open field exploration test (Figure 3, A-B) and light-dark transition box (Figure 3, E-H). The alcohol-withdrawn mice spent significantly less time in the center (p < 0.05) of the open field test compared with water-exposed mice (Figure 3A). Alcohol withdrawal also influenced the number of entries into the center (p < 0.01) of the open field (Figure 3B). Locomotor activity in the first 5 minute bout of the open field test was not significantly different between alcohol- and water-exposed mice (Figure 3C). However, alcohol-withdrawn mice displayed significantly lower locomotor activity compared with their water controls over a 60-minute period (Figure 3C). This effect was most pronounced after 24 hours of withdrawal and returned to control levels after 4 days of withdrawal (significant main effect of alcohol treatment: F1,10 = 5.225, p < 0.05; Figure 3D). Alcohol-withdrawn mice also made significantly fewer entries into the light side (p < 0.01) of the light-dark transition box compared with water controls (Figure 3E). The fewer entries in alcohol-withdrawn mice were not caused by a generalized decreased locomotor activity because there were no group differences (p = 0.44) in distance traveled (Figure 3H). Additionally, alcohol-withdrawn mice showed a longer latency, albeit not significant (p = 0.21), for their first light-side entry compared with water controls (Figure 3F). However, the two groups showed no clear difference (p = 0.58) in the amount of time spent in the light side (Figure 3G).

Figure 3. Mice daily gavaged with 3 g/kg alcohol demonstrate anxiolytic-related behaviors during alcohol withdrawal.

Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were given 3 g/kg alcohol or water via oral gavage once daily for five consecutive days for a duration of three weeks, and anxiety-like behaviors were measured using an open field exploration test (A-D) and light-dark transition box (E-H). Significance between groups was determined by unpaired t-test; **p < .01; *p < .05.

3.4 DORs play a protective role in a model of gavaged heavy alcohol intake

To investigate the role of DORs in AWiMA in our o.g. alcohol withdrawal model, we compared the severity and duration of AWiMA in WT and DOR KO mice after 15 sessions (three weeks) of 3 g/kg o.g. alcohol exposure. Mechanical sensitivity was measured prior to alcohol exposure (BL, baseline) and on days 1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 21 and 28 after alcohol administration (Figure 4A). AWiMA in mice exposed to o.g. alcohol was more pronounced and lasted longer than that observed in mice exposed to voluntary alcohol consumption (Figure 1B and 4B). Whereas mechanical sensitivity returned to baseline in 4-7 days for voluntary alcohol-exposed mice (Figure 1B), AWiMA persisted for 4 weeks for alcohol-gavaged mice (Figure 4B). Again, DOR KO mice showed prolonged duration of AWiMA compared to WT mice, with a clear significant main effect of time (F6,60 = 24.47, p < 0.001; Supplementary Figure 34). No significant main effect of genotype (F1,10 = 1.532, p = 0.24; Figure 4B) was noted; however, the cumulative AWiMA (measured as (100 – area under the mechanical sensitivity curve)day) was significantly higher in DOR KO than in WT mice after 21 days of alcohol withdrawal (p < 0.01; Figure 4C). Data was normalized to the von Frey response obtained in water-treated mice (Supplementary Figure 25).

Figure 4. Endogenous activity at delta opioid receptors attenuate alcohol withdrawal-induced mechanical allodynia in a model of gavaged heavy alcohol intake.

Timeline for chronic alcohol consumption and measurement of mechanical nociception of Figure 4B (A). Wild-type (WT) or DOR knockout (KO) C57BL/6 mice were given 3 g/kg alcohol or water via oral gavage (o.g.) once daily for five consecutive days for a duration of three weeks, and mechanical nociceptive sensitivity was examined on days 1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 21 and 28 after alcohol withdrawal using von Frey filaments. Significance between groups was determined by two-way ANOVA (B). The cumulative alcohol withdrawal-induced mechanical allodynia (AWiMA) (expressed in arbitrary units (AU)) in WT and DOR KO mice was calculated using the trapezoidal rule (C). **p < .01 normalized versus water-treated group.

3.5 Blockade of DORs during alcohol exposure prolongs duration of AWiMA

To further investigate the temporal aspect of involvement of DORs in the establishment of AWiMA, we pretreated mice with the DOR-selective antagonist naltrindole (NTI) before alcohol gavage administration. The NTI dosage was based on the lowest dose tested that did not induce mechanical allodynia in naïve mice (F1,38 = 7.333, p < 0.05; Figure 5A), as we found that administration of 2 mg/kg NTI acutely induced mechanical hypersensitivity (Figure 5A) and its chronic exposure led to prolonged hyperalgesia in naïve mice (Figure 5B). In contrast repeated administration of 0.2 mg/kg NTI did not cause hypersensitivity (significant main effect of NTI concentration: F1,12 = 12.43, p < 0.01 and time: F7,84 = 2.881, p < 0.01; Figure 5B). Data was normalized to the von Frey response obtained in saline/water-treated mice (Supplementary Figure 36). Wild-type C57BL/6 mice (n = 7-8) mice were subcutaneously injected with 0.2 mg/kg NTI or saline 30 minutes prior to gavage administration of 3 g/kg alcohol or water for two weeks (ten doses of NTI and alcohol in total; Figure 5C). Data was normalized to the von Frey response obtained in saline/water-treated mice (Supplementary Figure 37). Mice that received NTI prior to each alcohol administration displayed prolonged AWiMA compared to saline/alcohol-treated mice (Figure 5D and 5E). This was also illustrated by the cumulative AWiMA (measured as (100 – area under the mechanical sensitivity curve) day, p < 0.01) in Figure 5E.

Figure 5. Chronic naltrindole administration prior to each alcohol exposure prolongs duration of alcohol withdrawal-induced mechanical allodynia.

The acute subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of the DOR-selective antagonist naltrindole (NTI) dose-dependently caused mechanical allodynia in naïve mice (A). The chronic administration of 2 mg/kg NTI also led to prolonged hyperalgesia in naïve mice (B). Timeline for chronic alcohol consumption and measurement of mechanical nociception of Figure 4B (C). Twenty-two wild-type C57BL/6 mice were divided into three groups (n = 7-8), and were s.c. injected with 0.2 mg/kg NTI or saline. Thirty minutes after injection, each group was given 3 g/kg alcohol or water by oral gavage once daily for five consecutive days/week for two weeks. The mechanical sensitivity of all animals measured using von Frey filaments was examined on days 1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35 and 49 after alcohol withdrawal (D). The cumulative alcohol withdrawal-induced mechanical allodynia (AWiMA) (expressed in arbitrary units (AU)) was calculated using the trapezoidal rule (E). Data was normalized to the mechanical sensitivity response in saline/water-treated group. **p < .01; *p < .05. BL, baseline.

3.6 The DOR-selective agonist TAN-67 loses antinociceptive potency during active alcohol withdrawal

We next determined if TAN-67 could produce analgesia in naïve and alcohol-withdrawn WT mice. Intrathecal delivery of TAN-67 caused a dose-dependent decrease in mechanical sensitivity in mice exposed to either water or voluntary alcohol (Figure 6A, Table 1). No significant difference was observed in ED50 (F2, 57 = 0.113, p = 0.89). However, intrathecal injection of TAN-67 in mice exposed to 15 sessions (three weeks) of 3 g/kg o.g. alcohol followed by a 3-5 day withdrawal showed a right-ward shift in analgesic potency (F2, 53 = 9.320, p < 0.001) compared to mice exposed to water (Figure 6B, Table 1).

Figure 6. Potency of the DOR-selective agonist TAN-67 is reduced in mice withdrawn from gavaged alcohol but not volitional alcohol.

Naïve or alcohol-withdrawn C57BL/6 mice (n = 9-10) subjected to either voluntary (A) or gavage (B) administration were intrathecally injected with increasing doses of the DOR-selective agonist TAN-67, and mechanical antinociception was measured using von Frey filaments. Data are represented as a percentage of maximum possible effect (% MPE), which is defined as [(measurement − baseline) / (cutoff − baseline)] × 100.

Table 1.

Extrapolated ED50 values (95% Confidence Interval, nmol) for antinociception produced by the DOR-selective agonist TAN-67 in C57BL/6 mice exposed to water or alcohol in a voluntary or gavage model.

| TAN-67 | ED50 (95% CI, nmol) |

|---|---|

| Water (voluntary) | 61.0 (39.0-194) |

| Alcohol (voluntary) | 78.5 (42.7-577) |

| Water (gavage) | 131.5 (82.3-1023) |

| Alcohol (gavage) | 659 (319-10111) |

4. DISCUSSION

Alcohol use disorder is defined as a chronic, relapsing brain disease and as such carries a large socioeconomic burden (Heilig et al., 2010; Kliethermes, 2005). Heavy alcohol use and withdrawal is associated with neuropathy, hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia. Alcohol withdrawal induced allodynia is a component of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome, consisting of several separate symptoms including anxiety, tremors, depression or sleep disturbance (Becker, 2012; Egli et al., 2012; Saitz, 1998; Trevisan et al., 1998). These withdrawal symptoms are a large contributor to alcohol relapse. Currently, we lack detailed insight into mechanisms underlying the alcohol withdrawal syndrome, hampering development of novel medications that could treat the withdrawal symptoms and reduce relapse. Here we developed and validated a novel animal model of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome, with a strong mechanical allodynia component and identified the DOR as a contributor and potential target for AWiMA.

While models for alcohol withdrawal are available, they frequently rely on delivering alcohol to animals by inhalation or liquid diet, which is not necessarily related to the manner by which humans consume and abuse alcohol (Becker, 2013). We generated a novel alcohol withdrawal syndrome model using daily o.g. of 3 g/kg alcohol, mimicking a daily alcohol binge. Our model provided face validity as it rapidly produced severe and prolonged AWiMA (Figure 2) as well as withdrawal-induced anxiety-like behaviors (Figure 3) on a timescale similar to alcohol withdrawal in humans (Cecil et al., 2008; Edwards et al., 2012; Manasco et al., 2012). A benefit of our o.g. model is that AWiMA is more pronounced, longer-lasting and stable when compared to mice withdrawn from alcohol administered on a voluntary basis (compare Figure 1 and Figure 4). Clonidine, a centrally acting α2A-adrenergic receptor agonist clinically used in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal symptoms (Bjorkqvist, 1975; Lansford et al., 2008; Martin et al., 2006; Muzyk et al., 2011), produced potent analgesia in our alcohol withdrawal model, thereby also providing our model with construct validity.

The underlying mechanisms for AWiMA are not well understood. Recent studies have shown that DORs are expressed in neurons responding to mechanical stimulation and are heavily involved in the sensation of touch (Bardoni et al., 2014) even under naïve conditions (Scherrer et al., 2009; van Rijn et al., 2012). DORs have been effective in reducing chronic pain, including neuropathic pain (Crofford, 2010; Kabli and Cahill, 2007; Rowan et al., 2009) and thus are a logic plausible target for involvement in AWiMA. Using transgenic DOR KO mice, we confirm that DORs appear to play a protective role in AWiMA. Our observations in DOR KO mice however did not inform us at which stage DORs alleviate AWiMA. We therefore specifically blocked DORs only during alcohol exposure using the DOR-selective antagonist NTI (see methods). We reduced the alcohol exposure time from 2 weeks to 3 weeks in hopes of better differentiating severity and not only duration, yet onset of AWiMA was still fast and robust. Using this strategy, we revealed that without functional DORs, alcohol withdrawal produced prolonged AWiMA (Figure 5D and 5E). Thus, the presence of functional DORs may limit the emergence of algogenic factors following repeated alcohol exposure. One such an algogenic factor could be Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). TLR4s are expressed on neuroglia and have recently been implicated in the paradoxical hyperalgesia associated with chronic morphine use (Johnson et al., 2014; Watkins et al., 2009). Activation of TLR4 causes hyperalgesia (Calil et al., 2014; Watkins et al., 2009). Importantly, alcohol exposure can increase TLR4 expression and TLR4-facilitated secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators (Corrigan and Hutchinson, 2012; Floreani et al., 2010). One study has shown that the activation of DORs through mechanisms involving β-arrestin2 inhibit TLR4-induced release of tumor necrosis factor induced by the TLR4 agonist lipopolysaccharide in mast cells (Madera-Salcedo et al., 2013). It will be worthwhile to explore the role of TLR4 and potential TLR4-DOR crosstalk in the expression of AWiMA.

Current drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration for AUD treatment do not relieve alcohol withdrawal induced hyperalgesia or other components of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome. The National Institutes of Health has therefore declared that it is critically important to develop new and more effective pharmacological therapies for AUD. Besides a role in antinociception, DORs are implicated in alcohol consumption, depression and anxiety including alcohol withdrawal-induced anxiety (Filliol et al., 2000; Saitoh et al., 2004; van Rijn et al., 2010; Vergura et al., 2008). We and others have shown in preclinal animal models that the DOR-selective agonist TAN-67 can produce analgesia and reduce alcohol intake, depression and anxiety (Chiang et al., 2016; Kamei et al., 1995; van Rijn et al., 2010; van Rijn and Whistler, 2009). Hence, we were interested in investigating whether TAN-67, specifically, would alleviate AWiMA. We have previously shown that intrathecal administration of the DOR-selective agonists SNC80, DPDPE and deltorphin potently reduce mechanical sensation in naïve mice and that alcohol exposure does not change the analgesic potency of these DOR-selective agonists in mechanical allodynia, although DPDPE and deltorphin do show enhanced potency for thermal analgesia after alcohol exposure (van Rijn et al., 2012). The intrathecal route was chosen because primary and secondary neurons in the pain pathway are located in dorsal root ganglion and spinal cord and highly express DORs (Zhang et al., 1998). Additionally, the local administration would limit the TAN-67-induced-anxiolysis as a potential confounder. Consistent with our previous findings, TAN-67 dose-dependently reduced mechanical sensation in naïve mice and mice fully withdrawn from voluntary alcohol. However, we observed a significant decrease in TAN-67 potency in mice withdrawn from o.g. alcohol (Table 1). It is important to note that mice exposed to o.g. alcohol were injected with TAN-67 during active withdrawal (days 3-6; Figure 4), whereas mice voluntarily exposed to alcohol were injected with TAN-67 after withdrawal, as there was not stable hyperalgesia during active withdrawal (days 4-7; Figure 1). The loss of TAN-67 potency during withdrawal could potentially be attributed to DOR desensitization and internalization following endogenous opioid release due to the chronic exposure to 3 g/kg o.g. alcohol (Allouche et al., 1999; Bradbury et al., 2009; Gianoulakis, 2001; Pradhan et al., 2009). Previous reports have shown that chronic alcohol consumption significantly elevates the levels of methionine-enkephalin, an endogenous ligand for the DORs, with a peak after 7 days of alcohol ingestion (Banks et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2007; Marinelli et al., 2005; Oliva and Manzanares, 2007). Interestingly, pharmacological studies have suggested the existence of two DOR subtypes, DOR1 and DOR2 (Dietis et al., 2011; van Rijn et al., 2013). TAN-67 has frequently been labeled as a DOR1-selective agonist. The pharmacology underlying the subtypes is not well defined, but our data suggests that TAN-67 may interact with DOR-mu opioid receptor heteromers (van Rijn and Whistler, 2009) and have strong G-protein signaling bias, with limited efficacy for β-arrestin2 recruitment (Chiang et al., 2016). While our data would support DORs as a drug target for prevention but not treatment of AWiMA, it is important to consider that DOR agonists alleviate other components of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Also, different DOR agonists with an intermediate β-arrestin2 recruitment efficacy such as KNT-127 (Chiang et al., 2016; Nagase et al., 2010; Nozaki et al., 2014; Saitoh et al., 2011) may be more capable of reducing alcohol withdrawal induced hyperalgesia.

In conclusion, we have developed a robust mouse model of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome including AWiMA, which can be used to investigate mechanisms underlying this phenomenon. Our results indicate that DORs play a protective role against AWiMA; however, this role appears to be limited to the alcohol exposure stage. Our data also suggests that once mice reside in a state of severe alcohol withdrawal, DORs appear to be either desensitized or downregulated.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Establishment of a novel mouse model for alcohol withdrawal-induced allodynia

Delta opioid receptor KO mice have prolonged alcohol withdrawal-induced allodynia

Delta opioid receptor blockade prolongs alcohol withdrawal-induced allodynia

The delta agonist TAN-67 loses analgesic potency during active alcohol withdrawal

Acknowledgements

none

Role of Funding Source: nothing

Role of Funding Source: Richard M. van Rijn receives funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R00AA020539) and the Ralph W. and Grace M. Showalter Research Trust. This funding source had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Contributors

Doungkamol Alongkronrusmee: designed research, performed research, analyzed data, wrote paper

Terrance Chiang: performed research, bred and genotyped mice, analyzed data Richard M. van Rijn: designed research, performed research, analyzed data, wrote paper All authors have read and approved the submission of this manuscript

Author Disclosures:

Doungkamol Alongkronrusmee

Contributors: designed research, performed research, analyzed data, wrote paper

Conflict of Interest: none

Terrance Chiang

Contributors: performed research, bred and genotyped mice, analyzed data

Conflict of Interest: none

Richard M. van Rijn

Contributors: designed research, performed research, analyzed data, wrote paper

Conflict of Interest: none

REFERENCES

- Allouche S, Roussel M, Marie N, Jauzac P. Differential desensitization of human delta-opioid receptors by peptide and alkaloid agonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;371:235–240. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R, Mason BJ, Mattson ME, Miller WR, Pettinati HM, Randall CL, Swift R, Weiss RD, Williams LD, Zweben A. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Wolf KM, Niehoff ML. Effects of chronic ethanol on brain and serum level of methionine enkephalin. Peptides. 2003;24:1935–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardoni R, Tawfik VL, Wang D, Francois A, Solorzano C, Shuster SA, Choudhury P, Betelli C, Cassidy C, Smith K, de Nooij JC, Mennicken F, O'Donnell D, Kieffer BL, Woodbury CJ, Basbaum AI, MacDermott AB, Scherrer G. Delta opioid receptors presynaptically regulate cutaneous mechanosensory neuron input to the spinal cord dorsal horn. Neuron. 2014;81:1312–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC. Alcohol dependence, withdrawal, and relapse. Alcohol Res. Health. 2008;31:348–361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC. Effects of alcohol dependence and withdrawal on stress responsiveness and alcohol consumption. Alcohol Res. 2012;34:448–458. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v34.4.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC. Animal models of excessive alcohol consumption in rodents. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2013;13:355–377. doi: 10.1007/7854_2012_203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bie B, Zhu W, Pan ZZ. Ethanol-induced delta-opioid receptor modulation of glutamate synaptic transmission and conditioned place preference in central amygdala. Neuroscience. 2009;160:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkqvist SE. Clonidine in alcohol withdrawal. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1975;52:256–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1975.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury FA, Zelnik JC, Traynor JR. G protein independent phosphorylation and internalization of the delta-opioid receptor. J. Neurochem. 2009;109:1526–1535. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos RH. Pain and use of alcohol to manage pain: prevalence and 3-year outcomes among older problem and non-problem drinkers. Addiction. 2005;100:777–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calil IL, Zarpelon AC, Guerrero AT, Alves-Filho JC, Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ, Cunha TM, Verri WA., Jr. Lipopolysaccharide induces inflammatory hyperalgesia triggering a TLR4/MyD88-dependent cytokine cascade in the mice paw. PloS One. 2014;9:e90013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecil RL, Goldman L, Ausiello DA. Cecil medicine. Saunders Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chang GQ, Karatayev O, Ahsan R, Avena NM, Lee C, Lewis MJ, Hoebel BG, Leibowitz SF. Effect of ethanol on hypothalamic opioid peptides, enkephalin, and dynorphin: relationship with circulating triglycerides. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:249–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang T, Sansuk K, van Rijn RM. beta-Arrestin 2 dependence of delta opioid receptor agonists is correlated with alcohol intake. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016;173:332–343. doi: 10.1111/bph.13374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan F, Hutchinson M. Are the effects of alcohol on the CNS influenced by Toll-like receptor signaling? Exp. Rev. Clinical Immunol. 2012;8:201–203. doi: 10.1586/eci.11.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofford LJ. Adverse effects of chronic opioid therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010;6:191–197. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietis N, Rowbotham DJ, Lambert DG. Opioid receptor subtypes: fact or artifact? Br. J. Anaesth. 2011;107:8–18. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dina OA, Barletta J, Chen X, Mutero A, Martin A, Messing RO, Levine JD. Key role for the epsilon isoform of protein kinase C in painful alcoholic neuropathy in the rat. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:8614–8619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08614.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dina OA, Messing RO, Levine JD. Ethanol withdrawal induces hyperalgesia mediated by PKCepsilon. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;24:197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S, Koob GF. Neurobiology of dysregulated motivational systems in drug addiction. Future Neurol. 2010;5:393–401. doi: 10.2217/fnl.10.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S, Vendruscolo LF, Schlosburg JE, Misra KK, Wee S, Park PE, Schulteis G, Koob GF. Development of mechanical hypersensitivity in rats during heroin and ethanol dependence: alleviation by CRF(1) receptor antagonism. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1142–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli M, Koob GF, Edwards S. Alcohol dependence as a chronic pain disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012;36:2179–2192. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filliol D, Ghozland S, Chluba J, Martin M, Matthes HW, Simonin F, Befort K, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Valverde O, Maldonado R, Kieffer BL. Mice deficient for delta- and mu-opioid receptors exhibit opposing alterations of emotional responses. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:195–200. doi: 10.1038/76061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floreani NA, Rump TJ, Abdul Muneer PM, Alikunju S, Morsey BM, Brodie MR, Persidsky Y, Haorah J. Alcohol-induced interactive phosphorylation of Src and toll-like receptor regulates the secretion of inflammatory mediators by human astrocytes. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2010;5:533–545. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9213-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt JC. The state of pharmacotherapy for the treatment of alcohol dependence. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009;36:S15–23. quiz S24-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt JC, West SL, Carey TS, Lohr KN, Crews FT. Pharmacological treatment of alcohol dependence: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 1999;281:1318–1325. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatch MB, Lal H. Effects of ethanol and ethanol withdrawal on nociception in rats. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1999;23:328–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoulakis C. Influence of the endogenous opioid system on high alcohol consumption and genetic predisposition to alcoholism. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001;26:304–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW, Koob GF. Neurobiology of alcohol dependence: focus on motivational mechanisms. Alcohol Res. Health. 2008;31:185–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig M, Egli M, Crabbe JC, Becker HC. Acute withdrawal, protracted abstinence and negative affect in alcoholism: are they linked? Addict. Biol. 2010;15:169–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylden JL, Wilcox GL. Intrathecal morphine in mice: a new technique. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1980;67:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jochum T, Boettger MK, Burkhardt C, Juckel G, Bar KJ. Increased pain sensitivity in alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Eur. J. Pain. 2010;14:713–718. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Rolan PE, Johnson ME, Bobrovskaya L, Williams DB, Johnson K, Tuke J, Hutchinson MR. Codeine-induced hyperalgesia and allodynia: investigating the role of glial activation. Transl. Psychiatry. 2014;4:e482. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph EK, Levine JD. Multiple PKCepsilon-dependent mechanisms mediating mechanical hyperalgesia. Pain. 2010;150:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabli N, Cahill CM. Anti-allodynic effects of peripheral delta opioid receptors in neuropathic pain. Pain. 2007;127:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamei J, Saitoh A, Ohsawa M, Suzuki T, Misawa M, Nagase H, Kasuya Y. Antinociceptive effects of the selective non-peptidic delta-opioid receptor agonist TAN-67 in diabetic mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;276:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00026-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliethermes CL. Anxiety-like behaviors following chronic ethanol exposure. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005;28:837–850. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Alcoholism: allostasis and beyond. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2003;27:232–243. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057122.36127.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford CD, Guerriero CH, Kocan MJ, Turley R, Groves MW, Bahl V, Abrahamse P, Bradford CR, Chepeha DB, Moyer J, Prince ME, Wolf GT, Aebersold ML, Teknos TN. Improved outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer using a standardized care protocol for postoperative alcohol withdrawal. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:865–872. doi: 10.1001/archotol.134.8.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madera-Salcedo IK, Cruz SL, Gonzalez-Espinosa C. Morphine prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF secretion in mast cells blocking IkappaB kinase activation and SNAP-23 phosphorylation: correlation with the formation of a beta-arrestin/TRAF6 complex. J. Immunol. 2013;191:3400–3409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manasco A, Chang S, Larriviere J, Hamm LL, Glass M. Alcohol withdrawal. South. Med. J. 2012;105:607–612. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31826efb2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Fields HL, Hjelmstad GO, Mitchell JM. Delta-opioid receptor expression in the ventral tegmental area protects against elevated alcohol consumption. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:12672–12681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4569-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli PW, Bai L, Quirion R, Gianoulakis C. A microdialysis profile of Metenkephalin release in the rat nucleus accumbens following alcohol administration. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29:1821–1828. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183008.62955.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TJ, Kim SA, Eisenach JC. Clonidine maintains intrathecal self-administration in rats following spinal nerve ligation. Pain. 2006;125:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellion M, Gilchrist JM, de la Monte S. Alcohol-related peripheral neuropathy: nutritional, toxic, or both? Muscle Nerve. 2011;43:309–316. doi: 10.1002/mus.21946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzyk AJ, Fowler JA, Norwood DK, Chilipko A. Role of alpha2-agonists in the treatment of acute alcohol withdrawal. Ann. Pharmacother. 2011;45:649–657. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H, Kawai K, Hayakawa J, Wakita H, Mizusuna A, Matsuura H, Tajima C, Takezawa Y, Endoh T. Rational drug design and synthesis of a highly selective nonpeptide delta-opioid agonist, (4aS*,12aR*)-4a-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-2-methyl-1,2,3,4,4a,5,12,12a-octahydropyrido[3,4-b]acridine (TAN-67) Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 1998;46:1695–1702. doi: 10.1248/cpb.46.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H, Nemoto T, Matsubara A, Saito M, Yamamoto N, Osa Y, Hirayama S, Nakajima M, Nakao K, Mochizuki H, Fujii H. Design and synthesis of KNT-127, a delta-opioid receptor agonist effective by systemic administration. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:6302–6305. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki C, Nagase H, Nemoto T, Matifas A, Kieffer BL, Gaveriaux-Ruff C. In vivo properties of KNT-127, a novel delta opioid receptor agonist: receptor internalization, antihyperalgesia and antidepressant effects in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014;171:5376–5386. doi: 10.1111/bph.12852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obernier JA, White AM, Swartzwelder HS, Crews FT. Cognitive deficits and CNS damage after a 4-day binge ethanol exposure in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2002;72:521–532. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00715-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva JM, Manzanares J. Gene transcription alterations associated with decrease of ethanol intake induced by naltrexone in the brain of Wistar rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1358–1369. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese PS, Sultana M, Takemori AE. Naltrindole, a highly selective and potent non-peptide delta opioid receptor antagonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;146:185–186. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90502-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AA, Becker JA, Scherrer G, Tryoen-Toth P, Filliol D, Matifas A, Massotte D, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Kieffer BL. In vivo delta opioid receptor internalization controls behavioral effects of agonists. PloS One. 2009;4:e5425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JS, Best K, Belknap JK, Finn DA, Crabbe JC. Evaluation of a simple model of ethanol drinking to intoxication in C57BL/6J mice. Physiol. Behav. 2005;84:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, 3rd, King C. Self-report of alcohol use for pain in a multi-ethnic community sample. J. Pain. 2009;10:944–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roffey J, Rosse C, Linch M, Hibbert A, McDonald NQ, Parker PJ. Protein kinase C intervention: the state of play. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:268–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan MP, Ruparel NB, Patwardhan AM, Berg KA, Clarke WP, Hargreaves KM. Peripheral delta opioid receptors require priming for functional competence in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009;602:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh A, Kimura Y, Suzuki T, Kawai K, Nagase H, Kamei J. Potential anxiolytic and antidepressant-like activities of SNC80, a selective delta-opioid agonist, in behavioral models in rodents. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;95:374–380. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fpj04014x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh A, Sugiyama A, Nemoto T, Fujii H, Wada K, Oka J, Nagase H, Yamada M. The novel delta opioid receptor agonist KNT-127 produces antidepressant-like and antinociceptive effects in mice without producing convulsions. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;223:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R. Introduction to alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Health Res. World. 1998;22:5–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA . 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) SAMHSA; Rockville, MD: 2013. Table 5.8A—Substance Dependence or Abuse in the Past Year among Persons Aged 18 or Older, by Demographic Characteristics: Numbers in Thousands, 2012 and 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer G, Imamachi N, Cao YQ, Contet C, Mennicken F, O'Donnell D, Kieffer BL, Basbaum AI. Dissociation of the opioid receptor mechanisms that control mechanical and heat pain. Cell. 2009;137:1148–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster DJ, Kitto KF, Overland AC, Messing RO, Stone LS, Fairbanks CA, Wilcox GL. Protein kinase Cepsilon is required for spinal analgesic synergy between delta opioid and alpha-2A adrenergic receptor agonist pairs. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:13538–13546. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4013-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster DJ, Metcalf MD, Kitto KF, Messing RO, Fairbanks CA, Wilcox GL. Ligand requirements for involvement of PKCepsilon in synergistic analgesic interactions between spinal mu and delta opioid receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015;172:642–653. doi: 10.1111/bph.12774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumilla JA, Liron T, Mochly-Rosen D, Kendig JJ, Sweitzer SM. Ethanol withdrawal-associated allodynia and hyperalgesia: age-dependent regulation by protein kinase C epsilon and gamma isoenzymes. J. Pain. 2005;6:535–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spahn TW, Lohse AW, Otto G, Tettenborn B, Hopf HC, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH. Remission of severe alcoholic polyneuropathy after liver transplantation. Z. Gastroenterol. 1995;33:711–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevisan LA, Boutros N, Petrakis IL, Krystal JH. Complications of alcohol withdrawal: pathophysiological insights. Alcohol Health Res. World. 1998;22:61–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rijn RM, Brissett DI, Whistler JL. Dual efficacy of delta opioid receptor-selective ligands for ethanol drinking and anxiety. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010;335:133–139. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.170969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rijn RM, Brissett DI, Whistler JL. Emergence of functional spinal delta opioid receptors after chronic ethanol exposure. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;71:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rijn RM, Defriel JN, Whistler JL. Pharmacological traits of delta opioid receptors: pitfalls or opportunities? Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2013;228:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rijn RM, Whistler JL. The delta(1) opioid receptor is a heterodimer that opposes the actions of the delta(2) receptor on alcohol intake. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;66:777–784. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergura R, Balboni G, Spagnolo B, Gavioli E, Lambert DG, McDonald J, Trapella C, Lazarus LH, Regoli D, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, Calo G. Anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like activities of H-Dmt-Tic-NH-CH(CH2-COOH)-Bid (UFP-512), a novel selective delta opioid receptor agonist. Peptides. 2008;29:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LR, Hutchinson MR, Rice KC, Maier SF. The "toll" of opioid-induced glial activation: improving the clinical efficacy of opioids by targeting glia. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009;30:581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama A, Takagi T, Ishii H, Muramatsu T, Akai J, Kato S, Hori S, Maruyama K, Kono H, Tsuchiya M. Impaired autonomic nervous system in alcoholics assessed by heart rate variation. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1991;15:761–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Bao L, Arvidsson U, Elde R, Hokfelt T. Localization and regulation of the delta-opioid receptor in dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord of the rat and monkey: evidence for association with the membrane of large dense-core vesicles. Neuroscience. 1998;82:1225–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.