Abstract

Objective

Although efficacious interventions exist for childhood conduct problems, a majority of families in need of services do not receive them. To address problems of treatment access and adherence, innovative adaptations of current interventions are needed. This randomized control trial investigated the relative efficacy of a novel format of parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT), a treatment for young children with conduct problems.

Methods

Eighty-one families with three- to six-year-old children (71.6% male; 85.2% Caucasian) with diagnoses of oppositional defiant or conduct disorder were randomized to individual PCIT (n = 42) or the novel format, group PCIT. Parents completed standardized measures of children’s conduct problems, parenting stress, and social support at intake, posttreatment, and six-month follow-up. Therapist ratings, parent attendance, and homework completion provided measures of treatment adherence. Throughout treatment, parenting skills were assessed using the Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System.

Results

Parents in both group and individual PCIT reported significant improvements from intake to posttreatment and follow-up in their children’s conduct problems and adaptive functioning, as well as significant decreases in parenting stress. Parents in both treatment conditions also showed significant improvements in their parenting skills. There were no interactions between time and treatment format. Contrary to expectation, parents in group PCIT did not experience greater social support or treatment adherence.

Conclusions

Group PCIT was not inferior to individual PCIT and may be a valuable format to reach more families in need of services. Future work should explore the efficiency and sustainability of group PCIT in community settings.

Keywords: parent-child interaction therapy, PCIT, childhood conduct problems, group treatment, parent management training

The past forty years have seen meaningful advances in the treatment of childhood conduct problems. Parent management training (PMT), based primarily on behavioral principles, is the best-practice treatment for children with oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder, and several such interventions have been identified as well supported (Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008). However, now that efficacious treatments exist, the question has become how do we reach enough families to make a significant public health impact? Barriers at the system and family levels prevent many families from accessing services. A shortage of mental health professionals trained in effective interventions means that community agencies are overburdened (Satcher, 2000). Even when families do enter treatment, many drop out prematurely or do not participate fully, limiting the impact of services. It has been estimated that as many as 67% percent of children in need of services do not receive them (Kazdin, 2008).

To address problems with access, attrition, and adherence, innovative treatment delivery models are needed (Kazdin, 2008; Kazdin & Blase, 2011). We took a step to address these treatment barriers by evaluating an adaptation into a group format of the evidence-based intervention parent-child interaction therapy. PCIT has innovative characteristics, such as the live coaching of actual parent-child interactions, which make it a powerful intervention, while at the same time creating particular challenges to implementing it in a group format (Niec, Hemme, Yopp, & Brestan, 2005). In this randomized control trial, we explored two primary questions: (1) Do families who complete group PCIT demonstrate reductions of child conduct problems and increases in positive parenting skills that are not inferior to families who complete individual PCIT? (2) Does group PCIT offer benefits—specifically, increased parental social support, treatment retention and adherence—relative to individual PCIT?

Parent Management Training

PMT programs are frequently provided in a group format and have demonstrated efficacy in preventing and reducing children’s conduct problems (e.g., Pisterman et al., 1989; Ruma, Burke, & Thompson, 1996; Sheeber & Johnson, 1994; Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Beauchaine, 2011). Relative to the individual format of PMT, group parent training may have additional benefits. Because multiple families receive treatment with fewer therapist hours, group interventions offer a potential strategy to increase the availability of services. It has been further proposed that support among group members can decrease parents’ feelings of isolation. When parents develop relationships with families who have similar problems, it may reduce the stigma of having a “problem child” (Webster-Stratton & Herbert, 1993) and increase families’ perceptions of social support. Group treatment also allows opportunities for therapists to create a culture of positive peer pressure among families that may play a role in engaging parents in treatment and increasing retention (Niec et al., 2005). Little effort has been made to test these hypotheses (Levac, McCay, Merka, & Reddon-D’Arcy, 2008; Webster-Stratton, 1997); however, preliminary evidence suggests that the social support provided by group treatment may increase attendance (McKay, Harrison, Gonzalez, Kim & Quintana, 2002).

Despite the potential benefits of group parent training, there are limitations to existing models. For example, many parent training groups teach new skills in a didactic or video modeling format, then require parents to implement the skills at home and report on the outcome at the following session. This approach relies on parent reports regarding the implementation of skills and children's responses, with all the biases inherent in such reports (Feinberg, Neiderhiser, Howe, & Hetherington, 2001). If therapists do not observe parent-child interactions directly, they cannot assess and correct problems that are unreported, and parents lack the opportunity to practice the techniques with their children in a controlled setting (Herschell, Capage, Bahl, & McNeil, 2008). PCIT has several unique and innovative characteristics that avoid these limitations.

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy

PCIT is a PMT program designed to be implemented with individual families to address the conduct problems of children 2 to 6 years, 11 months of age (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011). The first phase of PCIT, Child-Directed Interaction (CDI), teaches parents to use child-centered skills such as labeled praises and descriptions of their children’s appropriate behaviors, reflections of appropriate verbalizations and imitation of appropriate play. At the same time, parents are taught to avoid leading verbalizations such as questions, commands, and criticisms. Therapists teach parents the use of child-centered skills and differential attention with the goal of improving the parent-child relationship and beginning to reduce children’s disruptive behaviors. In the second phase of PCIT, Parent-Directed Interaction (PDI), parents are taught how to use effective commands with consistent follow-through, including contingent praise for child compliance, a warning for noncompliance, and the use of an effective, developmentally appropriate time-out procedure for non-compliance.

PCIT differs from other parent training programs in at least three critical ways that may make a group adaptation particularly valuable: First, the intervention gives equal focus to the promotion of the parent-child relationship and the development of parents’ behavior management skills (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011). Because parent-child interactions in families with children exhibiting conduct problems are frequently negative and coercive in nature (e.g., Patterson, 1982; Stormont, 2002), a critical goal of PCIT is to increase positive, nurturing interactions. Second, in contrast to the traditional approaches to PMT (e.g., didactic and role play), parents rehearse new skills weekly in session through live interactions with their children. This provides the opportunity for direct coaching by the therapist, which is when the therapist gives immediate feedback on the parent’s skill development (e.g., from an observation room with a one-way mirror, while parents wear a radio-frequency earphone). Therapists use behavioral principles such as modeling, reinforcement, and differential attention in their coaching to shape parents’ behaviors as they occur (Barnett, Niec & Acevedo-Polakovich, 2013). Immediate feedback using behavioral principles has been shown to increase positive parenting skills (Shanley & Niec, 2010). Further, in a meta-analysis of the components of parent management training associated with positive changes in both children’s and parents’ behaviors, programs that included coaching of parent-child interactions had greater effect sizes than programs without this component (Kaminski et al., 2008). The active practice also allows the therapist to conduct ongoing behavioral assessments of each parent’s progress, which is the third way in which PCIT differs from most PMT models. In session, standardized coding of the parent-child interaction allows therapists to identify weaker parenting skills that need to be targeted in treatment and to recognize when a parent has reached mastery of the skills.

The robust outcomes of individual PCIT provide one rationale for investigating the adaptation of the intervention into a group format (e.g., Chaffin, Funderburk, Bard, Valle, & Gurwitch, 2011; Nixon, Sweeney, Erickson, & Touyz, 2004; Schuhmann, Foote, Eyberg, Boggs, & Algina, 1998). Families who complete PCIT demonstrate statistically and clinically significant reductions in children’s conduct problems and parents’ stress, as well as significant increases in positive parenting behaviors and children’s compliance (Nixon et al., 2004; Schuhmann, et al., 1998). PCIT has demonstrated efficacy in reducing the conduct problems of children from diverse ethnic backgrounds (McCabe & Yeh, 2009) and children with cognitive disabilities (Bagner & Eyberg, 2007). Further, positive changes during treatment generalize from the clinic to school settings (McNeil, Eyberg, Einsenstadt, Newcomb, & Funderburk, 1991) and from the targeted child to untreated siblings (Brestan, Eyberg, Boggs, & Algina, 1997). Maintenance of treatment gains is good, with families who complete PCIT showing positive gains maintained as long as six years post treatment (Hood & Eyberg, 2003).

We developed a group PCIT model that would maintain the core features of standard PCIT while adding the potential benefits of group treatment. As in the individual format, group PCIT has a dual focus on parent-child relationship enhancement (Child-Directed Interaction phase) and parent behavior management skills (Parent-Directed Interaction phase); children participate in all phases of the treatment; parents practice skills during live parent-child interactions; and therapists provide immediate feedback to parents. In addition to these core features, group PCIT provides parents with opportunities to develop relationships with one another. For example, parents actively observe and code one another during the live coaching of their interactions with their children. After each parent has been coded and coached, families provide one another with constructive feedback. This strategy has multiple benefits: it provides opportunities for vicarious learning; it allows parents to receive constructive feedback from their peers; and it provides opportunities for parents to support one another, fostering group cohesion.

Group PCIT may offer a valuable means of reaching more families in need of services. A small-scale (N = 27) pre-post evaluation of group PCIT in a community setting found that parents who completed PCIT reported reductions in their children’s conduct problems and demonstrated gains in positive parenting skills (Nieter, Thornberry, & Brestan-Knight, 2013). Although the study required only that parents express a need for parenting assistance, rather than children to meet criteria for a disruptive behavior disorder, the study supports the feasibility of conducting PCIT in a group format.

In the present study, we used a randomized control trial to investigate the outcomes for families with children diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder who completed either group or individual PCIT. We also evaluated the acceptability of both treatment formats, as acceptability of PMT models can predict adherence to the program (Reimers, Wacker, Cooper, & de Raad, 1992) and improvements in children’s behaviors (MacKenzie, Fite, & Bates, 2004). To control for treatment dosage, families in the individual and group PCIT conditions received the same number of PCIT sessions. PCIT was developed to be a mastery-based intervention, in that parents progress from the first phase of treatment (CDI) to the second phase (PDI) when they reach a specified level of competence with the child-centered parenting skills. Families successfully graduate from the program after mastery of the skills in both phases of treatment and their children’s conduct problems are within normal limits. However, session-limited PCIT has been identified as having similar long-term outcomes as standard PCIT (Nixon, Sweeney, Erickson, & Touyz, 2004), and time-limited PCIT has been evaluated in previous RCTs (e.g., Chaffin et al., 2004; Chaffin et al., 2011).

We expected that families in both treatments would demonstrate significant reductions in children’s conduct problems and increases in positive parenting, and that group PCIT would not be inferior to individual PCIT in either outcome. However, we expected that parents who had the benefit of peer support through group PCIT would report experiencing more social support, demonstrate greater treatment adherence, and manifest better retention than families in individual PCIT. Although we considered including a no-treatment control condition to investigate the efficacy of group PCIT, a review of the research revealed (a) consistency in the positive outcomes for individual PCIT including session-limited PCIT (i.e., reduction of childhood conduct problems, increases in positive parent-child interactions, reductions in parent stress) and (b) robust effects for parent behavior training in the treatment of conduct problems (e.g., Brestan & Eyberg, 1998; Chambless & Ollendick, 2001; Eyberg et al., 2008). Thus, we determined that sufficient evidence existed to suggest that group PCIT would be more efficacious than no treatment, and we conducted a more rigorous test of efficacy by comparing group PCIT to an individual PCIT condition.

Method

Participants

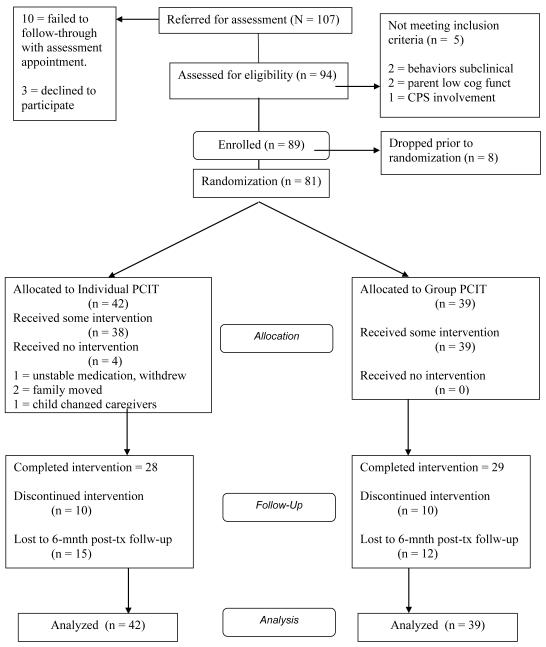

Families seeking services at a university mental health clinic were referred to receive information about the study when the primary complaint was conduct problems in their three- to six-year-old children. One hundred-seven families were referred and scheduled to meet with a study clinician to receive a thorough explanation of the project (Figure 1). Of the 107 referred families, 10 did not follow through with the scheduled appointment and three families declined to participate. Ninety-four families provided written informed consent, as approved by the [university withheld for blind review] human subjects review board, and completed measures to determine study eligibility. To be included in the study, children were required to meet diagnostic criteria for a DSM-IV diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or conduct disorder (CD, APA, 2000) and to have conduct problems rated by a caregiver in the clinical range of severity (i.e., BASC-II Externalizing Composite score of T > 70 or ECBI Intensity score of T > 60). Five families did not meet eligibility criteria and an additional eight families did not follow through to complete the initial assessment. Of the 81 children who were allocated to a treatment condition, 51 met criteria for ODD and 30 for CD. At least one caregiver was required to participate in treatment. Although participating caregivers included biological parents (78.8%) and other caregivers (e.g., grandparents, stepparents, 21.2%), for efficiency of communication, we refer here to male caregivers as “fathers” and female caregivers as “mothers.” Parents and children were excluded if they fell below a standard score of 70 on a cognitive screening measure and if there was a positive history of severe sensory or mental impairment (e.g., severe hearing impairments, pervasive developmental disorder). Families with active involvement in the child protective services system were also excluded and offered services outside of the study, as families in which abuse has occurred present different treatment issues and may require somewhat different interventions than those in which the primary problem is childhood conduct problems (Chaffin et al., 2004; Chaffin et al., 2011). Children were not excluded for concurrent treatment with psychoactive medication. Families whose children were taking psychotropic medication (n = 9) were evaluated only after the children’s behaviors had stabilized on the medication. Stabilization was defined as (1) parent satisfaction with the current dosage, (2) consistent dosage for at least one month, and (3) physicians’ verbalizations that further titration was not anticipated.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram.

Procedure

Following the recommendations of Kernan, Viscoli, Makuch, Brass, & Horwitz (1999), randomization was stratified by medication status into two strata: (1) children who were stabilized on medication and (2) children who were not on medication. That is, randomization was generated independently for families within each strata. Upon completion of the initial assessment, families were randomly assigned to one of two treatment conditions: (a) individual PCIT or (b) group PCIT.

Treatment conditions

PCIT was originally developed to be conducted by co-therapy teams to individual families (McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010). The therapists in this project were advanced doctoral students in clinical psychology who had completed the PCIT training workshop conducted by the first author (a clinical child psychologist with extensive expertise in PCIT and vetted by the developer of PCIT, Sheila Eyberg, PhD), observed a PCIT case, and participated in weekly PCIT supervision. In addition, all lead therapists had experience treating PCIT cases for at least one year. All 13 therapists and six evaluators attended workshops in administering and scoring structured interviews and behavior observations. The same therapists ran the PCIT groups and individual cases to maintain equivalence of therapists across treatment conditions. Because the treatment conditions only differed in their format (group versus individual), not their therapeutic protocols, contamination was not an issue. Core components of standard PCIT were maintained across both conditions; however, to control for dosage across conditions, the number of sessions was held constant. Table 1 summarizes the similarities and differences of the individual PCIT condition, group PCIT condition, and standard PCIT protocol (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011).

Table 1.

Comparison of PCIT Protocols

| Current PCIT Protocol* | Individual PCIT | Group PCIT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skills Targeted in CDI | Child-centered skills and differential attention; Decrease leading and directive parent behavior. |

Same as current | Same as current |

| Skills Targeted in PDI | Effective commands; Appropriate follow- through; Timeout sequence |

Same as current | Same as current |

| Orientation Session | None | Overview of PCIT | Overview; Promote group cohesion |

| Number of Sessions | Unlimited | 14 Orientation; CDI Didactic & 4 coaching sessions; PDI Didactic & 7 coaching sessions |

14 Orientation; CDI Didactic & 4 coaching sessions; PDI Didactic & 7 coaching sessions |

| Termination Criteria | Parent meets CDI & PDI mastery criteria Child behavior WNL |

None | None |

| Number of Families | 1 | 1 | 3-7 dyads |

| In-session Behavior Assessment (DPICS) |

Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Daily Homework | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PDI Coaching #1 | Meet individually | Meet individually | Meet individually |

| Group Parents Observe Each Other during P-C Interactions. |

No | No | Yes |

| Group Parents Receive Feedback from Other Parents |

No | No | Yes |

Note: From Eyberg & Funderburk (2011).

Individual PCIT

Individual PCIT sessions were held once a week for approximately one hour. The principles and skills of responsive and consistent parenting were presented during the CDI Teach Session using didactic, modeling, and role play, followed by four coaching sessions in which the therapists provided in vivo feedback to parents who were actively practicing the skills with their children. Parents then learned about the use of effective commands and discipline (PDI Teach Session) and completed seven coaching sessions focused on these skills. Parents were asked to practice the skills at home during daily play sessions with their children (five minutes each day during the child-directed phase of treatment; 10-15 minutes a day during the parent-directed phase, which included five minutes of child-directed play and time to practice effective commands with the appropriate follow-through). For more information about the PCIT protocol see Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011).

Group PCIT

The aim of the group protocol was to maintain the unique aspects of PCIT, while including strategies to develop the potential benefits of group parent training. As in individual PCIT, group PCIT included the same didactic and coaching sessions (reference withheld for blind review). Also similar to individual PCIT, two therapists led the groups. However, PCIT with multiple families required minor modifications that distinguished it from the original PCIT protocol and from other group models. For instance, sufficient time was required to coach each parent-child dyad. For this reason, group sessions were two hours long and groups contained three to seven parent-child dyads (i.e., two to five families with one to four caregivers in each family).

Initial group sessions focused on maximizing group cohesion by encouraging rapport among parents, establishing group guidelines, and setting a collaborative tone conducive to therapeutic gain. Parents were encouraged to identify constructive similarities with other parents (e.g., that they were all attending treatment to learn new ways of managing their children’s behaviors). Therapists were trained to identify, prevent, and correct counterproductive discussion using a variety of therapeutic techniques (e.g., reframing, redirection, and differential attention). All group process concerns were discussed in weekly supervision.

Thirteen of the fourteen sessions in the group PCIT model (93%) were conducted with all the members of the group present. Only during one of the fourteen sessions did parents meet with therapists individually: that was the coaching session in which parents implemented the new discipline procedure for the first time (PDI Coach 1). This PCIT session is sometimes longer because parents are just learning the procedure and children are learning and testing their parents’ new responses to noncompliance. As has been described elsewhere (reference withheld for blind review), the individual session provides parents and children the time and attention they need to negotiate the discipline process for the first time. However, as previously implemented within a small-scale community sample (Nieter, et al., 2013), all the subsequent PDI coach sessions (six out of seven) were conducted in a group format, which provided families with the opportunity to (1) learn and become comfortable with the discipline process by observing other parents successfully completing it, and (2) support one another during difficult discipline scenarios. For example, parents observing other families during a time-out sequence frequently gave encouraging statements that the therapist communicated via the bug-in-the-ear (e.g., “You’re doing such an amazing job staying calm!”; “Wow! Stick with it!”).

Because make-up sessions were offered to families within the same week as the missed session, a few families received an additional individual session. Six of the 39 families allocated to group PCIT received a total of nine make-up sessions. No family received more than two make-up sessions. No group sessions were held that did not include at least two families, although one group was discontinued when all three families ended treatment within the same two sessions. The mean number of families enrolled in each of the 11 groups was 3.5 and the mean number completing treatment in each group was 2.6 (74%; Range = 0-4 families)

As in individual PCIT, the final group session included specific discussion of what families could do to maintain treatment gains and how to deal with setbacks or new problems that might arise in the future. Specific to the group condition, families were encouraged to seek positive support from one another.

Treatment Fidelity

A number of procedures were implemented to help maintain treatment fidelity throughout the study. First, all assessment and treatment clinicians completed comprehensive training (described above). To increase fidelity during sessions, both the group and individual PCIT treatment manuals included outlines of the primary components to be addressed during each session, which the therapists checked as they completed. All study clinicians received weekly supervision on every case. In addition, there was frequent live observation of sessions by the supervisor. Questions regarding protocol implementation that could not be clearly resolved with the PCIT manual were discussed with Dr. Eyberg.

Finally, all treatment sessions were recorded to assess fidelity upon completion. Evaluation of fidelity was rigorous, using advanced PCIT therapists, who were not therapists in the study, to review a random selection of the recorded sessions from both treatment conditions. A total of 435 session components (e.g., reviewing parents’ homework, defining skills, correctly implementing the pre-coaching behavior observation, providing adequate coaching time) were reviewed for fidelity in a total of 70 sessions. Ratings demonstrated high treatment fidelity (88% for group and individual treatment formats).

Measures

Wonderlic Personnel Test (WPT)

The WPT is a 50-item test designed as a screening scale of adult intelligence (Dodrill, 1981). In a sample of 120 normal adults, the WPT estimate of intelligence correlated 0.93 with the WAIS Full Scale IQ score, and the WPT score was within 10 points of the WAIS IQ score for 90% of the subjects (Dodrill, 1981, Dodrill & Warner, 1988). We used the WPT Timed Score as a cognitive screening measure for parents.

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Third Edition (PPVT-III)

The PPVT-III is a standardized test that measures receptive language in individuals aged 2.6 years through adulthood (Dun & Dunn, 1997). The PPVT-III correlates 0.90 with the Wechsler Intelligence Test for Children—Third Edition Full Scale IQ (Dun & Dunn, 1997), and was used in this study as a cognitive screening measure for child participants.

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (NIMH DISC IV-P)

The NIMH-DISC-IV-P is a highly structured diagnostic interview for administration to parents (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). It includes all common mental disorders of children included in the DSM-IV that are not dependent on specialized test procedures. One-week test-retest reliability on administration to parents of 9- to 17-year-old children has been reported at 0.54 for ODD and 0.54 for CD (Grills & Ollendick, 2002). We consulted with Sheila Eyberg (trained by C. Lucas at Columbia University) on the modifications to certain questions needed for developmentally appropriate administration to parents of children as young as three years. We used the ODD and CD modules of the DISC to assess whether children met criteria for study inclusion.

Behavioral Assessment System for Children—II; Parent Rating Scale 2-5 year olds & Parent Rating Scale 5-11 year olds (BASC-II)

The BASC-II is a broad-band rating scale developed to assess the behaviors of children 2 through 18 years of age (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). The measure yields a variety of scales including scales of Externalizing Problems, Internalizing Problems, a Behavior Symptoms Index, and an Adaptive Skills Scale. Reliability and validity of the scale have been found to be good. The BASC has shown sensitivity in discriminating various groups of clinic-referred children including children with conduct problems (Whitcomb & Merrell, 2013). Test-retest reliability is good (0.81 - 0.92 for the Behavior Symptoms Index for children 2-11 years), suggesting that without intervention, scores remain stable (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). The BASC Externalizing Problems Composite Score was used as a criterion for study inclusion. The Externalizing, Internalizing, and Adaptive Skills Composite Scores provided measures of treatment outcome.

Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI)

The ECBI is a 36-item inventory developed to measure parents’ perceptions of the conduct problems of children 2 through 16 (Eyberg & Pincus, 1999). The Intensity Scale (IS) measures the frequency of conduct problems on a seven-point scale from 1 (Never) to 7 (Always). The IS has yielded an internal consistency coefficient of 0.95; interrater (mother-father) reliability coefficients of 0.69 (Eyberg & Pincus, 1999), and without treatment, has shown good long-term (10 month) test-retest reliability (Funderburk, Eyberg, Rich, & Behar, 2003). The ECBI has demonstrated sensitivity to treatment effects (Eisenstadt, et al., 1993; Schuhmann, et al., 1998; Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1997) and has good sensitivity and specificity related to the identification of children with oppositional defiant and conduct disorder (Rich & Eyberg, 2001). We used the ECBI IS as a criterion for study inclusion and as a primary measure of treatment outcome.

Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System-III (DPICS-III)

The DPICS-III is a behavioral observation measure developed to assess the quality of parent-child interactions in a standardized format (Eyberg, et al., 2010; Robinson & Eyberg, 1981). Parent-child dyads referred for the treatment of childhood conduct problems differ from non-referred parent-child dyads on a number of DPICS variables (Forster, Eyberg, & Burns, 1990; Webster-Stratton, 1985). The DPICS also demonstrates sensitivity to treatment effects (Schuhmann, et al., 1998). In the present study, during treatment sessions in which parents were coached (i.e., weeks 2-5, 7-13), parents were first observed in the Child Led Play (CLP) situation of the DPICS. The CLP situation is meant to assess parents’ acquisition of responsive parenting skills. Frequencies of parent “Do Skills” (e.g., praises, behavior descriptions, and reflections) and “Don’t Behaviors” (questions, commands, and negative talk) were coded from the video-recorded measure to examine skill acquisition across treatment conditions over time.

To assess interrater reliability in the current sample, eight hundred and twenty-five five-minute video-recorded segments of the DPICS were coded by a primary coder blind to the study hypotheses. Prior to coding for this study, the primary coder was trained intensively in the DPICS-III coding system, had met criteria (Kappa > 0.80 for all categories) with an expert-rated tape, and has been coding DPICS for four years when this project began. Interrater coders at an outside institution independently coded 211 (25%) randomly selected segments. Interrater coders were blind to study hypotheses, participants’ treatment condition, and phase of treatment. Interclass correlation coefficients were calculated on the child-centered interaction skills (“Do Skills”), as well as those behaviors targeted to be reduced (“Don’t Behaviors”; Table 2). Of the seven codes, all demonstrated at least adequate reliability (r > .65) and five demonstrated good to excellent reliability (r > .80).

Table 2.

Interrater Reliability of the Weekly DPICS-III Parent Variables

| “Do Skills” | “Don’t Behaviors” | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 211 | UP | LP | RF | BD | QU | CO | NTA |

| ICC = | .76 | .80 | .81 | .84 | .91 | .65 | .67 |

Note. UP = Unlabeled Praise, LP = Labeled Praise, RF = Reflection, BD = Behavior Descriptions, QU = Questions, CO = Commands, NTA = Negative Talk (criticisms).

Treatment adherence

We measured three aspects of participants’ treatment adherence: (a) session attendance, (b) self-reported completion of weekly homework assignments, and (c) therapist-rated in-session participation.

Number of sessions attended

Therapists maintained attendance records for each participant. Therapists were available for families to schedule make-up sessions within one week of a missed appointment.

Homework completion

The number of homework assignments that caregivers completed was also used to assess treatment adherence. Following the initial CDI coaching session, caregivers were asked to complete a daily 5-minute rehearsal of skills with their children at home for the six days of the week they did not attend therapy sessions. During PDI coaching sessions, practice of the discipline procedure was added to the rehearsal of child-centered skills and later generalized to other times of the day. Caregivers recorded their homework completion including the dates, the type of practice, and any problems they encountered.

Therapist-rated participation

Immediately subsequent to each session, both therapists rated each caregiver’s participation. Level of participation was rated for each caregiver on a 3-point scale (1 = seldom, 2 = sometimes, 3 = frequent), and ratings were averaged across therapists. A similar scale has been used to assess treatment adherence in other parenting programs (e.g., Webster-Stratton, 1990). Because the current study used the mean participation scores across raters, reliability for this measure was computed using the average-measures intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC[2]), which indicates the reliability of a mean score. The ICC(2) for parent participation was 0.64, indicating acceptable reliability.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support-Child Behavior, (MSPSS-C)

The MSPSS-C is a 16-item self-report questionnaire adapted from the original MSPSS (Niec, Cochran & Stayer, 2003; Zimet, et al., 1988) to assess parents’ perceived social support from family, friends, significant others, and other parents, specifically in relation to their children with conduct problems. Items are scored on a seven-point scale that ranges from “very strongly disagree” to “very strongly agree.” Similar to the original scale, internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the Total Score was high (0.90). Concurrent validity has been supported by demonstrating associations between the MSPSS-C Total Score and measures of parent stress, parent psychopathology, children’s behavior problems, and parent-child attachment in a sample of families referred for treatment of child behavior problems (Niec et al., 2003).

Parenting Stress Index-Short Form, (PSI-SF)

The PSI-SF is a 36-item parent self-report instrument designed to measure the relative degree of stress in a parent-child relationship and to identify the sources of distress (Abidin, 1995). The Total Stress score of the PSI-SF has correlated 0.94 with the Total Stress score of the full PSI. Test-retest reliability was 0.84 over a six-month interval. On the long-form PSI, it has been found that higher scores are associated with increased severity of conduct-disordered behavior (Eyberg, Boggs, & Rodriguez, 1992; Ross, Blanc, McNeil, Eyberg, & Hembree-Kigin, 1998). PSI scores are sensitive to treatment changes with young children (Eisenstadt, et al., 1993). In this study, the PSI-SF Total Score was a measure of treatment outcome and demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.92).

Therapy Attitude Inventory, (TAI)

The TAI was designed to assess parental satisfaction with the process and outcome of therapy (Eyberg, 1993). It consists of 10 multiple-choice questions addressing the impact of parent training on areas such as confidence in discipline skills, quality of the parent-child interaction, the child’s behavior, and overall family adjustment. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the TAI was 0.92 in the current study. Previous research has demonstrated discriminative validity between outcomes of alternative treatments (Eisenstadt, et al., 1993; Eyberg & Matarazzo, 1980). We used the TAI total score to compare parent satisfaction at posttreatment between group and individual conditions.

Results

Randomization Check and Assessment of Nesting

We conducted conservative intention-to-treat analyses, maintaining all participants within the dataset after their randomized assignment to treatment condition and imputing missing outcome data forward based on the last observation (Higgins & Green, 2011). Hypothesis testing was conducted with significance set at p-values of less than 0.05. Prior to testing the primary hypotheses, treatment groups were compared for equivalence on all major demographic variables. Chi-square analyses revealed no significant differences in the distribution of children’s medication status, gender, ethnicity and race or caregivers’ ethnicity and race across groups. Similarly, no significant differences were found on children’s ages and receptive vocabulary scores or caregivers’ ages, cognitive functioning, and education levels (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographics of the Group and Individual PCIT Conditions

| Group | Individual | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| % or M | n or SD | % or M | n or SD | t or χ2 | |

| Child age | 4.12 | 1.01 | 4.33 | 1.35 | t (78) = −0.82 |

| Child PPVT-III | 98.21 | 13.38 | 96.72 | 15.78 | t (78) = 0.45 |

| Child gender | χ2(1) = 0.65 | ||||

| Boys | 74.4% | 29 | 69% | 29 | |

| Girls | 25.6% | 10 | 31% | 13 | |

| Child ethnicity (Hispanic) | 8.57% | 3 | 0% | 0 | χ2(1) = 3.31 |

| Child race | χ2(2) = 2.84 | ||||

| White | 84.6% | 33 | 85.7% | 36 | |

| Native American | 5.1% | 2 | 0% | 0 | |

| Multi-racial | 7.7% | 3 | 11.9% | 5 | |

| Not reported | 2.6% | 1 | 2.4% | 1 | |

| Child medication status (yes) | 7.89% | 3 | 14.63% | 6 | χ2(1) = 0.89 |

| Caregiver cog functioning | 99.46 | 15.29 | 99.22 | 15.19 | t(122) = 0.09 |

| Primary caregiver age | 32.57 | 8.69 | 31.07 | 7.01 | t (78) = 0.85 |

| Other caregiver age | 36.42 | 10.96 | 33.97 | 10.07 | t (77) = 0.93 |

| Primary caregiver education | 13.99 | 2.70 | 13.63 | 2.34 | t (77) = 0.62 |

| Other caregiver education | 14.06 | 2.47 | 13.09 | 2.63 | t (77) = 1.54 |

Note: All means are reported in years, except the child PPVT-III, which is the standard score of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III, and the caregiver cog functioning, which is the timed score of the Wonderlic Personnel Test (transformed onto the standard IQ scale).

The data collected from families who participated together within a group cannot be assumed to be independent; they present a level of nesting that is often neglected in analyses of the efficacy of group interventions. Therefore, prior to testing the primary hypotheses, we used Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) analyses to estimate the degree of nesting exhibited by study variables within specific groups in the group PCIT condition (HLM 7 software; Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & du Toit, 2011). This nesting was examined with a three–level HLM model using only the participants in group PCIT: the time of observation was treated as the first level of analysis (e.g., intake, posttreatment, follow-up), the caregiver was treated as the second level, and the specific therapy group was treated as the third level. These analyses were conducted separately for mothers and fathers. Significant variation between level 3 units (therapy groups) was used to determine the effect of group membership while controlling for other sources of variation. As an exception, the TAI (which was only collected at posttreatment) was tested using a two-level model, with variance between therapy groups reflecting the variance between level 2 units.

Using Wald chi square tests of significance, most variables did not display a significant amount of variation between therapy groups, with a few exceptions explained next. Results suggested that therapy group membership accounted for 23% of the variance in mother TAI scores (χ2 = 16.92, p = .05) and 38% of the variance in father TAI scores (χ2 = 13.27, p = .04). This effect was not surprising, as one’s specific therapy group is likely to influence one’s satisfaction with the therapy overall. Group membership also accounted for 33% of the variance for father ratings on the Adaptability Scale of the BASC-II (χ2 = 24.36, p = .004). For mothers, therapy group membership accounted for significant variance on the DPICS-III behavior observation measure: 25% of the variance for the parenting “Do Skills” (χ2 = 35.24, p = .000) and 30% of the variance for the parenting “Don’t Behaviors” (χ2 = 22.99, p = .000). Statistical tests that include a nested variable tend to underestimate the standard errors and thus increase the likelihood of Type I error (Hox, 2010). Although these few outcome variables exhibited a nesting effect from specific therapy groups, the resulting bias in our statistical tests is muted by the fact that the nesting only exists in half of the sample and frequently for only one set of caregivers. Regardless, significant effects regarding nested variables warrant some caution in interpretation.

Child Behavioral Functioning

We examined changes in children’s behavioral and emotional functioning across time (intake, posttreatment, six-month follow-up) and treatment condition (group or individual PCIT) using repeated measures MANOVAS. The ECBI Intensity Scale and the BASC-II Externalizing Problems Composite, Internalizing Behaviors Composite, and Adaptive Skills Composite were compared for mothers’ and fathers’ reports separately (See Table 4 for descriptive statistics and Table 5 for MANOVA statistics). Parent reports of child functioning demonstrated a significant main effect for time (Mothers: F (8, 70) = 16.78, p = .000; Pillai’s Trace = 0.66, partial η2 = .66; Fathers: F (8, 33) = 4.99, p = .000; Pillai’s Trace = 0.55, partial η2 = .55), but not for treatment (Mothers: F (4, 74) = .86, p = .495; Pillai’s Trace = 0.04, partial η2 = .04; Fathers: F (4, 37) = 1.62, p = .190; Pillai’s Trace = 0.15, partial η2 = .15). Across time, children not only experienced a reduction of conduct problems, but also a reduction of internalizing symptoms and an increase in adaptive behaviors. The results of planned comparisons with a Least Significant Differences test indicated that fathers and mothers rated their children’s externalizing and internalizing symptoms on the BASC-2 as significantly less severe from intake to posttreatment and from intake to follow-up. Fathers and mothers also rated their children as having significantly more adaptive behaviors from intake to posttreatment, and intake to follow-up. Neither mothers nor fathers had a significant interaction effect between time and treatment condition. That is, for both mothers and fathers, children’s externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms decreased over time and adaptive skills increased regardless of treatment format.

Table 4.

Parent Report of Child and Parent Functioning

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Group PCIT n = 39 |

Individual PCIT n = 42 |

Group PCIT n = 22 |

Individual PCIT n = 24 |

|||||

|

|

||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| BASC-II Externalizing Composite | ||||||||

| Intake | 72.84 | 13.34 | 74.81 | 12.15 | 65.50 | 10.13 | 69.58 | 11.10 |

| Posttreatment | 65.69* | 13.76 | 68.33 | 14.51 | 58.09* | 9.48 | 65.42 | 11.15 |

| Follow-up | 62.44 | 12.85 | 67.36 | 14.14 | 59.73 | 9.43 | 64.13 | 12.10 |

| BASC-II Internalizing Composite | ||||||||

| Intake | 64.13 | 16.58 | 60.71 | 12.81 | 56.00 | 9.02 | 57.92 | 11.75 |

| Posttreatment | 58.23 | 17.28 | 57.00 | 13.37 | 53.50* | 9.30 | 55.42 | 11.58 |

| Follow-up | 54.10 | 15.62 | 55.88 | 13.87 | 52.55 | 9.52 | 53.96 | 11.69 |

| BASC-II Adaptability Scale | ||||||||

| Intake | 41.82 | 10.35 | 39.36 | 8.79 | 42.50 | 7.18 | 37.33 | 8.83 |

| Posttreatment | 42.64* | 9.64 | 42.12 | 9.09 | 44.82* | 8.27 | 39.92 | 9.43 |

| Follow-up | 42.77 | 10.41 | 42.21 | 7.93 | 44.59 | 8.86 | 41.33 | 10.42 |

| ECBI Intensity Scale | ||||||||

| Intake | 163.42 | 24.84 | 170.74 | 27.23 | 147.53 | 28.07 | 166.58 | 22.98 |

| Posttreatment | 129.03* | 40.00 | 134.55 | 41.93 | 112.71* | 35.72 | 138.58 | 36.26 |

| Follow-up | 123.90 | 38.12 | 137.36 | 36.68 | 116.19 | 35.01 | 135.52 | 36.19 |

| PSI-SF Total Stress Score | ||||||||

| Intake | 106.74 | 19.48 | 100.50 | 17.94 | 92.63 | 11.34 | 93.15 | 15.48 |

| Posttreatment | 97.89 | 19.45 | 90.40 | 17.34 | 84.83* | 14.82 | 90.23 | 16.06 |

| Follow-up | 93.69 | 21.92 | 90.00 | 17.61 | 86.87 | 15.13 | 85.55 | 19.92 |

| MSPSS-C | ||||||||

| Intake | 79.80 | 16.03 | 79.74 | 17.64 | 72.95 | 17.62 | 78.25 | 13.62 |

| Posttreatment | 82.13 | 18.08 | 82.18 | 17.95 | 80.14 | 22.61 | 81.79 | 14.90 |

| Follow-up | 81.15 | 17.33 | 83.10 | 17.46 | 79.55 | 21.82 | 82.17 | 15.05 |

Note: One-sided t-test indicated statistically non-inferior results in the Group PCIT compared to the individual PCIT (δ = 10% of the individual PCIT condition mean). N’s for analyses with mother scores ranged from 73 (PSI) to 80 (BASC scales). N’s for analyses with fathers ranged from 43 (ECBI and PSI) to 44 (BASC scales) BASC-II = Behavioral Assessment System for Children-II; ECBI = Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory; BASC-II composites are T-scores; All other scores are raw scores. MSPSS-C = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support-Child Behavior.

Table 5.

Repeated-Measures Multivariate Analysis of Variance of Parent Report of Child Behavioral Functioning

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| df | F | ηp2 | p | df | F | ηp2 | p | |

| BASC-II Externalizing Composite | ||||||||

| Condition | 1,77 | 1.02 | .01 | .315 | 1,40 | 3.44 | .08 | .071 |

| Time | 1.64, 126.10 | 39.07 | .34 | .000 | 1.54, 61.75 | 20.68 | .34 | .000 |

| Time × Condition | 1.64, 126.10 | 1.74 | .02 | .305 | 1.54, 61.75 | 1.39 | .03 | .255 |

| BASC-II Internalizing Composite | ||||||||

| Condition | 1,77 | .28 | .00 | .596 | 1,40 | .56 | .01 | .458 |

| Time | 1.73, 133.51 | 26.41 | .26 | .000 | 1.35, 53.95 | 7.92 | .17 | .003 |

| Time × Condition | 1.73, 133.51 | 3.08 | .06 | .056 | 1.35, 53.95 | .03 | .00 | .921 |

| BASC-II Adaptability Scale | ||||||||

| Condition | 1,77 | .36 | .01 | .548 | 1,40 | 3.81 | .09 | .058 |

| Time | 1.89, 145.31 | 3.51 | .04 | .035 | 1.81, 72.51 | 5.21 | .12 | .010 |

| Time × Condition | 1.89, 145.31 | .44 | .01 | .632 | 1.81, 72.51 | .49 | .01 | .596 |

| ECBI Intensity Scale | ||||||||

| Condition | 1,77 | 1.50 | .02 | .224 | 1,40 | 5.85 | .13 | .020 |

| Time | 1.86, 143.18 | 78.13 | .50 | .000 | 1.19, 47.73 | 33.96 | .46 | .000 |

| Time × Condition | 1.64, 143.18 | .66 | .01 | .509 | 1.19, 47.73 | .47 | .01 | .532 |

Note: Greenhouse-Geisser correction for violations of sphericity; BASC-II = Behavioral Assessment System for Children-II; ECBI = Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory.

On the ECBI Intensity Scale, a narrowband measure of the frequency of children’s conduct problems, mothers’ reports showed a significant main effect for time, but not for treatment condition. Fathers’ reports on the ECBI Intensity Scale demonstrated significant differences across time and treatment condition, with fathers in the group PCIT condition rating their children’s conduct problems as less severe than those in the individual PCIT condition. Pairwise comparisons revealed that according to both mothers and fathers, children’s conduct problems decreased significantly from intake to posttreatment and intake to follow-up. Neither mothers’ nor fathers’ reports of children’s conduct problems on the ECBI Intensity Scale demonstrated significant interactions between time and treatment condition.

A primary goal of the study was to test the efficacy of group PCIT relative to individual PCIT; thus, we conducted analyses to determine whether the group condition yielded non-inferior posttreatment scores relative to the individual condition. Non-inferiority tests were conducted using a one-sided equivalence t-test, as outlined by Walker & Nowacki (2010). Although a standard equivalence range (δ) has not been established in prior PCIT research, research in other domains has generally used a set percentage of the control group mean to determine δ. The current study used 10% of the individual PCIT condition mean as the acceptable range of non-inferiority, which was the same threshold used between control and treatment groups for the MMPI by Rogers, Howard, & Vessey (1993). The results for the non-inferiority tests are noted in Table 4. The group PCIT condition was not inferior to the individual PCIT condition for eight out of the ten comparisons, including the primary outcome variable, child conduct problems, as rated by both mothers and fathers on the BASC Externalizing Problems Composite and the ECBI Intensity Scale. Mothers’ ratings of children’s internalizing problems and parent stress served as the two exceptions to the findings of non-inferiority.

Parent Functioning

Parent stress

We examined changes in mothers’ and fathers’ stress across time and treatment condition using repeated measures ANOVAS (Tables 4 and 6). As expected, mothers and fathers experienced a significant main effect in their parenting stress levels for time but not treatment condition. Pairwise comparisons indicated that mothers and fathers demonstrated a significant decrease in parenting stress from intake to posttreatment, and intake to follow-up. Neither mothers nor fathers had a significant interaction effect across time and treatment condition.

Table 6.

Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance of Parent Reports of Stress and Social Support

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| df | F | η p2 | p | df | F | η p2 | p | |

| PSI-SF | ||||||||

| Condition | 1,70 | 2.31 | .03 | .133 | 1,42 | 2.77 | .06 | .631 |

| Time | 1.63, 114.14 | 23.18 | .25 | .000 | 1.75, 71.74 | 12.09 | .23 | .000 |

| Time × Condition | 1.63, 114.14 | .49 | .01 | .573 | 1.75, 71.74 | .23 | .03 | .268 |

| MSPSS-C | ||||||||

| Condition | 1,79 | .27 | .04 | .851 | 1,42 | .32 | .01 | .459 |

| Time | 1.46, 115.40 | 1.47 | .02 | .234 | 1.45, 60.95 | 9.63 | .17 | .001 |

| Time × Condition | 1.46, 115.40 | .25 | .00 | .709 | 1.45, 60.95 | .47 | .00 | .565 |

Note. PSI-SF = Parent Stress Index- Short Form. MSPSS-C = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support-Child Behavior. Greenhouse-Geisser correction for violations of sphericity.

Parenting Skills Acquisition

Analyses on the development of positive parenting skills over time were performed using HLM with restricted maximum likelihood (RML) estimation, which improves estimation accuracy for studies with smaller level 2 sample sizes (n < 100). The significance of the fixed regression coefficients (γ) were tested as means upon the t-distribution, and the significance of the random coefficients (variance components) were tested using the Wald χ2 test (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). The effect size for the growth function was assessed by standardizing the regression coefficients as β. A two-level HLM model was tested for fathers and mothers separately for each set of primary outcomes (“Do Skills” and “Don’t Behaviors”). Analyses for mothers included 544 observations nested within 65 caregivers, whereas analyses for fathers included 247 observations nested within 35 caregivers (See Table 7).

Table 7.

HLM Results for Parent Skills Acquisition

| Effects for Mothers | Model 1: “Do Skills” | Model 2: “Avoid Skills” | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | γ (S.E.) | β | γ (S.E.) | β |

| Intercept (γ00) | 17.49 (1.07) | -- | 18.37 (1.21) | -- |

| Growth function (γ01) | 2.50** (0.35) | 0.21 | −2.48** (0.41) | −0.27 |

| PCIT Formata (γ10) | −0.03 (2.02) | 0.00 | −0.04 (1.81) | 0.00 |

| Interaction (γ11) | 0.04 (0.71) | -- | 1.03 (0.91) | -- |

| Random Effects | Coefficient | Pseudo R2 | Coefficient | Pseudo R2 |

| Level 1 variance (σ2) | 60.58 | 0.00 | 21.94 | 0.00 |

| Intercept variance (τ00) | 40.45** | 0.00 | 83.67** | 0.00 |

| Growth curve variance (τ11) | 2.21* | 0.00 | 8.69** | 0.00 |

|

| ||||

| Effects for Fathers | Model 1: “Do Skills” | Model 2: “Avoid Skills” | ||

|

| ||||

| Fixed Effects | γ (S.E.) | β | γ (S.E.) | β |

| Intercept (γ00) | 17.79 (1.94) | -- | 17.85 (1.49) | -- |

| Growth function (γ01) | 2.01** (0.63) | 0.17 | −1.88** (0.33) | −0.18 |

| PCIT Formata (γ10) | −1.88 (3.18) | −0.07 | −0.85 (2.97) | 0.04 |

| Interaction (γ11) | 0.87 (1.25) | -- | −0.13 (0.66) | -- |

| Random Effects | Coefficient | Pseudo R2 | Coefficient | Pseudo R2 |

| Level 1 variance (σ2) | 44.71 | 0.00 | 27.08 | 0.00 |

| Intercept variance (τ00) | 106.33** | 0.00 | 68.79** | 0.00 |

| Growth curve variance (τ11) | 9.79** | 0.00 | 1.12* | 0.02 |

Note: p < .01,

p < .05. In calculating Pseudo R2, baseline variance estimates for mothers were σ2 = 59.77, τ00 = 39.84, τ11 = 2.17 for model 1 and σ2 = 21.95, τ00 = 82.52, τ11 = 8.56 for model 2. Baseline estimates for fathers were σ2 = 44.70, τ00 = 105.96, τ11 = 9.67 for model 1 and σ2 = 27.08, τ00 = 66.72, τ11 = 1.14 for model 2.

Gives the relationship between participating in Group PCIT (vs. Individual) and the outcome. Estimated prior to entering the cross-level interaction.

The time variable was centered such that “0” reflected the behavioral scores for the first week, with each unit reflecting one week’s time and increasing up to 11. Examination of scatter and mean plots revealed a pattern of change in which scores tended to increase or decrease (depending on the behavioral outcome) for the first few weeks and then level off, indicating parents’ tendency to gain skills rapidly early in treatment. To statistically model the growth patterns illustrated in the scatterplot, the time variable was transformed by taking its square root. This transformation would predict notable gains in parenting skills for the first weeks and smaller gains in the last few weeks. Consistent with the nonlinear patterns observed in the scatterplot, preliminary analyses indicated that the transformed time values (square root function) outperformed the untransformed values (linear function) in predicting skill acquisition scores over the course of treatment. Thus, all skill acquisition models used a square root function to examine the growth in parental skills over time. Patterns of change for both the “Do Skills” and “Don’t Behaviors” for mothers and fathers were consistent with predictions. That is, parents’ child-centered skills significantly increased and their negative behaviors significantly decreased over time (See Tables 8 and 9 for descriptive statistics).

Table 8.

Parents’ “Do Skills” across Treatment Sessions

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Group PCIT | Individual PCIT |

Group PCIT | Individual PCIT |

|||||

|

| ||||||||

| Session | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| CDI 1 | 14.97 | 1.68 | 15.70 | 1.46 | 16.44 | 2.56 | 15.00 | 2.99 |

| CDI 2 | 21.38 | 3.49 | 19.82 | 1.99 | 20.33 | 2.91 | 25.40 | 4.45 |

| CDI 3 | 23.15 | 2.43 | 20.85 | 2.14 | 19.42 | 3.83 | 21.07 | 3.07 |

| CDI 4 | 26.26 | 2.89 | 23.58 | 2.61 | 19.75 | 3.06 | 27.85 | 3.92 |

| PDI 1 | 25.57 | 3.10 | 24.29 | 1.86 | 22.11 | 4.02 | 25.18 | 4.23 |

| PDI 2 | 23.36 | 2.82 | 23.16 | 1.41 | 25.3 | 4.07 | 24.58 | 3.15 |

| PDI 3 | 27.05 | 2.64 | 24.71 | 1.68 | 27.00 | 6.24 | 21.83 | 2.60 |

| PDI 4 | 27.41 | 3.18 | 26.15 | 1.89 | 28.46 | 4.24 | 22.92 | 2.69 |

| PDI 5 | 25.52 | 2.42 | 26.76 | 1.74 | 23.50 | 4.19 | 24.17 | 3.32 |

| PDI 6 | 22.93 | 2.24 | 23.29 | 1.92 | 22.00 | 4.47 | 26.10 | 2.54 |

| PDI 7 | 29.20 | 2.89 | 24.88 | 2.16 | 29.00 | 4.44 | 22.18 | 2.80 |

Note: “Do Skills” = sum of praises, reflections, and behavior descriptions by parent toward child during five-minute DPICS Child-led Play interaction; CDI = Child-directed Interaction coaching session; PDI = Parent-directed Interaction coaching session.

Table 9.

Parents’ “Don’t Behaviors” across Treatment Sessions

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Group PCIT | Individual PCIT |

Group PCIT | Individual PCIT |

|||||

|

| ||||||||

| Session | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| CDI 1 | 19.94 | 1.86 | 22.778 | 2.33 | 17.94 | 2.19 | 20.07 | 2.77 |

| CDI 2 | 13.21 | 1.83 | 15.32 | 1.58 | 16.67 | 3.41 | 17.00 | 3.56 |

| CDI 3 | 13.74 | 2.00 | 14.26 | 1.19 | 10.17 | 2.31 | 14.21 | 3.47 |

| CDI 4 | 12.39 | 1.76 | 11.85 | 1.67 | 14.42 | 2.49 | 10.54 | 2.63 |

| PDI 1 | 11.43 | 2.20 | 11.82 | 1.27 | 13.33 | 3.40 | 11.27 | 3.29 |

| PDI 2 | 9.36 | 1.79 | 10.72 | 1.63 | 8.20 | 1.70 | 12.25 | 4.21 |

| PDI 3 | 8.80 | 1.57 | 10.04 | 1.33 | 8.80 | 2.92 | 12.33 | 3.51 |

| PDI 4 | 9.82 | 1.91 | 9.85 | 1.17 | 9.85 | 1.91 | 10.62 | 2.02 |

| PDI 5 | 11.57 | 2.02 | 11.92 | 1.67 | 11.80 | 2.64 | 12.67 | 3.94 |

| PDI 6 | 11.85 | 2.21 | 10.04 | 2.06 | 15.17 | 4.48 | 12.80 | 4.54 |

| PDI 7 | 9.80 | 1.55 | 10.00 | 1.54 | 9.25 | 1.70 | 11.81 | 3.23 |

Note: “Don’t Behaviors” = sum of questions, commands, and negative talk by parent toward child during five-minute DPICS Child-led Play interaction; CDI = Child-directed Interaction coaching session; PDI = Parent-directed Interaction coaching session.

In order to test the interaction between time and treatment format, variance in the growth functions between caregivers was tested in the models for changes over time to determine if this variance should be modeled in subsequent analyses. Results indicated statistically significant variation in the growth function for all behavioral outcomes and samples. As a result, analyses with these outcomes included an additional random coefficient to reflect the variance in growth functions between caregivers (τ11): that is, differences in the rate of change between caregivers. Estimates of the caregiver variance between intercepts (τ00) along with estimates of growth functions between caregivers (τ11), were used for comparison with the model that includes the primary predictor—i.e., PCIT format—to determine if the relative variance was accounted for by treatment condition. The analysis of the impact of PCIT format took the model for change over time and entered treatment condition at the second level. The model examined the ability of PCIT format to explain intercept differences among caregivers (reflecting a main effect) and to explain differences in the growth functions among caregivers (reflecting an interaction between the predictor and the growth function). There were no main effects for treatment condition and no interaction effects between treatment condition and time (Table 7). That is to say, variance in parents’ skill acquisition for both the “Do Skills” and “Don’t Behaviors” for both mothers and fathers occurred over time and often reflected individual differences, but were not impacted by whether parents were in group or individual PCIT.

Clinical Significance

To explore the clinical significance of changes in child and parent functioning, we computed the percentage of cases demonstrating reliable change between the intake and posttreatment measurements for primary outcome measures. The reliable change index (RC) was computed using the procedure proposed by Jacobson, Follette, & Revenstorf (1984), and the standard error of measurement was computed using the normative test-retest reliability of the measure. RC indices more extreme than the ±1.96 indicated either a reliable increase or decrease in functioning, with the direction depending on the specific measure. The percentage of cases showing reliable improvement according to mothers’ reports was 60% for child conduct problems as assessed by the ECBI; 36.3% for externalizing behaviors, 58.8% for internalizing behaviors, and 18.5% for adaptability on the BASC, and 31.5% for parental stress. For fathers, the percentage of cases showing reliable improvement was 53.5% for ECBI-rated child conduct problems, 27.3% for externalizing problems, 20.5% for internalizing problems, and 18.2% for adaptability on the BASC, and 20.9% for parental stress. Further, of the 28 families who completed individual PCIT, 20 children (71%) moved from the clinical range at intake to within normal limits at six-month follow-up on the ECBI Intensity Scale. Similarly, of the 29 families who completed group PCIT, 20 children (69%) moved from the clinical range to within normal limits.

Coaching Time

One challenge of implementing PCIT in a group format is ensuring that parents receive sufficient in vivo coaching (Niec et al., 2005). In order to test whether the amount of coaching that parents received varied across treatment conditions, we conducted independent samples t-tests for mothers and fathers. The mean amount of coaching time per session for mothers did not significantly differ for participants in group and individual PCIT (group PCIT coaching in minutes M(SD) = 18.98(9.75), individual PCIT coaching in minutes M(SD)= 19.91(9.00); t(603) = −1.22, p = .22; Cohen’s d = 0.10). Fathers, however, received significantly less coaching if they participated in individual PCIT, M(SD)= 15.52(5.81), rather than group PCIT (M(SD)= 18.69(8.24); t(268) = 3.69, p < .001; Cohen’s d = −0.45).

Attrition, Adherence and Social Support

Attrition

Of the 81 families allocated to an intervention, 77 began treatment (Figure 1). Fifty-seven of the 77 families completed treatment, for an overall intervention attrition rate of 26%. Group PCIT had an attrition rate of 25.6% (n = 10), while individual PCIT had an attrition rate of 26.3% (n = 10). The phi coefficient testing the association between treatment condition and attrition was not significant (ϕ = −.01, p > .05).

Adherence

Families’ adherence to treatment was assessed in three ways: a) number of sessions attended, b) parent-reported completion of weekly homework assignments, and c) therapist-rated in-session participation. To test whether the format of PCIT affected parents’ adherence, we conducted independent samples t-tests on each measure. Neither mothers nor fathers demonstrated significant differences in attendance, homework completion, or therapist ratings of participation across treatment conditions. In other words, treatment adherence as assessed from three different perspectives was not statistically different for group and individual PCIT (Table 10).

Table 10.

Parent Adherence to Treatment

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Group PCIT | Individual PCIT | Group PCIT | Individual PCIT | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Participation | 2.78 | 0.31 | 2.77 | 0.31 | 2.48 | 0.60 | 2.46 | 0.58 |

| Homework | 4.07 | 1.11 | 3.92 | 1.19 | 3.17 | 1.35 | 3.32 | 1.31 |

| Attendance | 12.28 | 4.08 | 10.72 | 4.99 | 9.81 | 5.35 | 9.32 | 4.87 |

Note. Independent samples t-tests for all comparisons between Group and Individual PCIT conditions were not statistically significant.

Social support

Repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to evaluate the effects of treatment condition and time on mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of social support as rated on the MSPSS-C (Tables 4 and 6). Fathers, but not mothers, showed a significant main effect for time, with fathers reporting experiencing significantly more social support from intake to posttreatment and intake to follow-up. Neither mothers nor fathers demonstrated a significant effect for treatment condition. Contrary to the hypothesis that parents in group treatment would report more social support after treatment, there were no significant interaction effects across time and treatment condition for either parents.

Treatment Satisfaction

Independent samples t-tests revealed that parents reported high levels of satisfaction with PCIT (above 40 on a fifty-point scale) regardless of whether it was delivered in a group or individual format (Mothers Individual PCIT M(SD) = 44.60(4.27); Mothers Group PCIT M(SD) = 45.06(4.20), t(100) = 0.54, p > .05; Cohen’s d = −0.11; Fathers Individual PCIT M(SD) = 43.87(3.76); Fathers Group PCIT M(SD) = 45.52 (3.60), t(36) = −1.36, p > .05; Cohen’s d = −0.45).

Discussion

Young children with conduct problems are at high risk for serious negative consequences as they reach school-age and adolescence, including for example, poor academic functioning, peer rejection, antisocial activity, incarceration and substance abuse (Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, & Milne, 2002; Van Lier & Koot, 2010). Research indicates that early interventions are more effective in comparison to interventions for older children (Frick, 2012). However, system factors such as the cost of services and shortages of child mental health staff, and family factors such as premature termination and poor treatment adherence prevent many families from benefiting from services (Kazdin, 2008; Satcher, 2000).

To begin addressing the problems of availability and adherence, we evaluated the relative efficacy of an innovative adaptation of parent-child interaction therapy, group PCIT. The study design was rigorous in that the innovative model was tested against an individual format of PCIT. Results suggest that group PCIT is an efficacious intervention with outcomes that are not inferior to individual PCIT. Families participating in group PCIT experienced improvements in multiple domains of functioning as assessed by differing methods and sources. That is, parents reported reductions in their children’s conduct problems and internalizing symptoms, as well as increases in their children’s adaptive skills. Parents also reported significant reductions in their parenting stress. Effect sizes for reductions in child conduct problems and parenting stress were large, which is consistent with an earlier trial of PCIT (McCabe & Yeh, 2009; child conduct problems Cohen’s d = 1.41; parenting stress Cohen’s d = 1.04). The improvement in child functioning experienced by families in group PCIT were not inferior to those experienced by families in the individual condition. Further, observations of parenting behaviors demonstrated that parents’ child-centered skills increased significantly during treatment, while negative parent behaviors decreased. Similarly to the parent-reported improvements, the observed changes in parents’ behaviors over time were not influenced by the format of PCIT that families received. Treatment gains were not only statistically significant, but also demonstrated clinical significance. The findings are promising as children whose conduct is within the typical range of functioning are less likely to experience negative consequences in later childhood and adolescence than those whose conduct remains disturbed.

Challenges and Benefits of Group PCIT

One of the challenges identified when implementing PCIT in a group format is ensuring that every parent receives a sufficient amount of coaching during each session (Niec et al., 2005). Our comparison of coaching time across treatment conditions revealed that families did not receive less coaching in the group format. This finding helps to allay concerns that a group format of PCIT must sacrifice coaching time for other elements of the intervention or that it is impossible to give parents in a group sufficient coaching to alter their skills. While we did find that fathers who participated in group PCIT received more coaching than fathers in individual PCIT, we encourage caution in interpreting this result. Within the individual format, when two parents participate in treatment, the second parent coached receives less therapist coaching. This disparity is meant to be eliminated by alternating the order of parents coached across treatment sessions. If, counter to the protocol, therapists do not routinely rotate parents’ order of coaching, one parent will receive less coaching overall. Alternating coaching order may be clinically valuable, as it allows parents to interact with their children in different conditions (e.g., at the beginning or the end of the play) and to observe their partner using the parenting skills prior to their own coaching. Although parents in the group format were coached in alternating order, the potential to inadvertently receive less coaching did not arise as each parent-child dyad was coached for approximately the same amount of time in every session.

One of the hypothesized benefits of group parenting interventions is the opportunity for parents to interact with other parents of children with difficult behaviors. When caregivers develop relationships with others who have similar experiences, it may reduce their perceptions of stigma around having a child with conduct problems (Webster-Stratton & Herbert, 1993). Although some research has proposed that the reduction of stigma and existence of group support may help to engage families in treatment (Webster-Stratton, 1997; Webster-Stratton & Herbert, 1993), our findings did not support the hypothesis that parents participating in group PCIT would experience greater feelings of social support as relates to their children. It is worth noting that despite the lack of statistically significant differences across treatment conditions on our measure of social support (MSPSS-C), anecdotal evidence suggests that group PCIT provided opportunities to receive support that the individual format did not. For instance, families in group treatment routinely reported calling one another with reminders to complete homework or questions about skill use. In some groups, families carpooled to sessions. Families reported planning post-group activities and presented therapists with group pictures. While we did not systematically assess this qualitative information and therefore cannot interpret it, the possibility exists that the lack of differences on the MSPSS-C may be due in part to a failure to tap the types of support experienced in group treatment. The qualitative evidence suggests that additional study of the potential differential benefits of group PCIT is warranted.

Similar to the findings for social support, families in group PCIT demonstrated no significant differences in their treatment adherence relative to families in individual PCIT. While group PCIT cannot therefore be considered superior to individual PCIT in this domain, our finding does counter the concern that the group format does not provide families with enough tailored attention to maintain their participation. Furthermore, while as many as 40% to 60% of children who begin outpatient mental health treatment drop out prematurely (Kazdin, 2008), the overall intervention attrition rate for this study was 26%, with no differences across conditions. Finally, not only did families in group PCIT demonstrate treatment adherence that did not differ from families in individual PCIT, they also expressed as much satisfaction with the intervention. In both conditions, treatment satisfaction was high.

Limitations and Future Directions

While treatment attrition for families in group and individual PCIT was relatively low, study attrition was somewhat higher, with 33% of families who were allocated to an intervention failing to complete the follow-up assessment six months after treatment. No significant differences in study attrition occurred across treatment conditions (36% = Individual PCIT, 31% = Group PCIT; ϕ = −.05, p > .05), but attrition at follow-up limits our ability to draw conclusions regarding the maintenance of treatment effects. Maintaining study participation in clinical research has long been a challenge (Foster & Bickman, 1996). Research on participant follow-up in longitudinal designs suggests that one key factor to reducing attrition is maintaining contact with participants during the follow-up period (David, Alati, Ware, & Kinner, 2013). A number of other strategies have been described to improve retention, such as providing rewards, establishing a recognizable study “brand” with logos on all contacts, maintaining regular tracking, and designing brief follow-up assessments (Mason, 1999). Although we implemented retention strategies consistent with the literature (e.g., obtaining multiple contacts for families, keeping families informed of the follow-up schedule, providing reasonable rewards for completing assessments, providing interim phone calls midway between posttreatment and follow-up), they were insufficient to obtain good retention rates (< 20%; Mason, 1999). Future research should continue to explore study, therapist, and family factors in parent management training research that contribute to retention.

The underlying goal of this study was to determine whether group PCIT may be a valuable option to help address shortages in the availability of evidence-based interventions for young children with conduct problems. Our findings suggest that group PCIT is an efficacious intervention, with important parent and child outcomes comparable to individual PCIT. Further, the findings here support the feasibility of using the live coaching model, which is central to PCIT, in a group format. Future work remains necessary to determine whether group PCIT reduces barriers to treatment. Specifically, we recommend consideration of the following issues.

First, the PCIT protocol in the present study differed from the standard PCIT protocol (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011) in an important aspect: families did not progress in treatment based on their mastery of parenting skills; rather, families in both group and individual PCIT moved through treatment at the same pace. This design allowed us to control for the impact of dosage on treatment outcome across formats, and was consistent with past research that used session-limited PCIT (e.g., Chaffin et al., 2011; Nixon et al., 2004). However, limiting the number of treatment sessions may have implications for families’ success and maintenance of treatment gains. Some findings suggest that families who remain in treatment until their children’s behaviors are within normal limits may have more time to establish their acquisition of parenting skills and maintain gains longer (Eyberg et al., 2014). While treatment gains in the present study remained significant from intake to six-month follow-up, given the limitations already expressed, it would be valuable to evaluate the outcome of time-limited group PCIT with a longer follow-up period prior to broadly disseminating the model.

Second, although parents’ CDI skills (“Do Skills”) were evaluated throughout treatment with a behavioral observation measure (DPICS), PDI skills were not regularly assessed. It is important to note that in both treatment conditions parents were taught the same sequence of child discipline techniques and all parents were required to complete daily homework to practice the new techniques. Subsequent to this instruction, children’s conduct problems were significantly reduced. However, future evaluation of the group format should collect additional data regarding parents’ use of the discipline strategies.

Third, the cost of implementing group PCIT must be considered. Assumptions have sometimes been made about the costs of group interventions. A few early studies focused on the reduced therapist time that is required to implement groups as an indication of its “cost-effectiveness,” without computing actual cost-effectiveness analyses (Barkley, 1987; Brightman, Baker, Clark, & Ambrose, 1982). Group PCIT may be a successful way to reduce the costs of treatment for families. For instance, when multiple families are treated simultaneously, fewer sessions may be cancelled for families who don’t show, thus improving therapists’ productivity. Especially within community agencies, greater productivity may make an intervention more sustainable. However, a need remains to investigate the actual costs of group PCIT before decisions are made regarding the most economical format of the intervention.

Finally, it is important to note that within the group PCIT condition, some measures of outcome were influenced by the specific therapy group in which a family participated. Therapy group influenced both mothers’ and fathers’ treatment satisfaction, and also influenced mothers’ acquisition of child-centered parenting skills. Although the sample size of this study did not allow for exploration of group characteristics that might make a PCIT group more or less effective, future research should examine these factors. Furthermore, clinicians considering implementing group treatment should be deliberate in their selection of families, as our findings indicate that the composition of the group may matter to family outcome.

Clinical Implications