Abstract

Digital media are often used to encourage smoking cessation by increasing quitline call volume through direct promotion to smokers or indirect promotion to smoker proxies. The documentation of a program’s experiences utilizing digital media is necessary to develop both the knowledge base and a set of best practices. This case study highlights the use of digital media in a proxy-targeted campaign to promote the California Smokers’ Helpline to health care professionals from October 2009 to September 2012. We describe the iterative development of the campaign’s digital media activities and report campaign summaries of web metrics (website visits, webinar registrations, downloads of online materials, online orders for promotional materials) and media buy (gross impressions) tracking data. The campaign generated more than 2.7 million gross impressions from digital media sources over 3 years. Online orders for promotional materials increased almost 40% over the course of the campaign. A clearly defined campaign strategy ensured that there was a systematic approach in developing and implementing campaign activities and ensuring that lessons learned from previous years were incorporated. Discussion includes lessons learned and recommendations for future improvements reported by campaign staff to inform similar efforts using digital media.

Keywords: Communications Media, Smoking Cessation, Health Campaigns

INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE

In 2012, 81% of adults in the United States used the Internet, and 72% of those reported using the Internet to search for health information in the past year (Fox & Duggan, 2013). In 2004, an estimated 7%, or 8.4 million, of US Internet users reported having searched online for information about smoking cessation (Fox, 2005). In response to this widespread use and availability of the Internet, public health programs have used health-related websites to communicate health information, promote their programs, and deliver innovative behavior change interventions (Walters, Wright, & Shegog, 2006). As of March 2012, 91% (i.e., 48 of 53 US states or territories) of tobacco cessation programs sponsored smoking cessation websites, 38 of these sites offered self-help tools, and 34 offered interactive counseling online, such as those offered on the national portal “smokefree.gov” (North American Quitline Consortium, 2012).

Digital advertising, (emails, web pages, banner ads, text messages, interactive voice recordings, hand-held computers and digital TV) is a type of innovative promotional strategy that may play an increasingly important role in the future of smoking cessation campaigns because of its advantages over traditional advertising approaches (Brendryen & Kraft, 2008). Digital media channels are anonymous, able to handle a virtually unlimited volume of participants, available 24 hours per day, available for repeat use, and able to tailor information to users’ needs (Cline & Haynes, 2001). Because of these advantages, digital media has the potential to enhance the reach and cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions (Strecher, 1999; Walters, Wright, & Shegog, 2006).

In the context of population-based smoking cessation interventions, innovative promotional strategies, including digital advertising and websites, are often used to increase quitline call volume by directly targeting consumers (i.e., smokers who are interested in quitting or recent quitters looking for assistance to stay abstinent). State tobacco control programs (TCPs) may also indirectly increase quitline call volume among smokers by targeting messages to smoker proxies (e.g., health care providers, friends or family of smokers) (Zhu, 2006; Brockman, 2012). However, public health programs face a variety of challenges when using the Internet in media campaigns.

While advertising delivered to users by digital media may have desirable characteristics, the Internet is also a diverse and disorganized environment that can be difficult for public health programs to navigate for reaching target populations (Kohl, 2013). Thus, some public health programs may struggle to build or maintain traffic to their websites. These difficulties are potentially compounded by the fact that programs may lack sufficient time and resources (staff or monetary) to direct and sustain web traffic to their websites. In addition, some programs do not explicitly define measureable objectives or to identify specific target audiences for their web properties. As a result, a formal evaluation of online efforts may not occur, and testing the efficacy of such interventions is rare (Japuntich et al., 2006). Since there is currently no widespread evaluation of online health promotion or tobacco cessation interventions, there is limited published research to guide the development and implementation of new tobacco control efforts that use digital media.

This case study describes the promotion efforts of a recent California Smokers’ Helpline campaign to target health care professionals with cessation messaging. The campaign relied heavily on digital media and during the three years of promotion, the campaign staff developed a set of lessons learned to guide future efforts. This information may help tobacco control programs to better understand the methods, costs, and benefits of this approach.

The California Tobacco Control Program and the California Smokers’ Helpline

The California Tobacco Control Program (CTCP) supports a free, statewide, smoking cessation telephone service known as the California Smokers’ Helpline (1-800-NO-BUTTS). The California Smokers’ Helpline has been in service since 1992. Services provided by the University of California-San Diego’s Moores Cancer Center include self-help materials, referrals to local programs, and individual telephone counseling offered in a variety of languages (e.g., English, Spanish, Cantonese, Korean, Mandarin, and Vietnamese). In addition, the Helpline also offers specialized services for teens, pregnant women, the deaf and hard of hearing, and smokeless tobacco (chew) users, as well as information for proxy callers, such as friends or family of tobacco users.

Similarly, the Helpline website offers tailored information for smokers, health care professionals, and smokeless tobacco (chew) users. The website is accessible by two separate URLs (www.NoButts.org and www.CaliforniaSmokersHelpline.org), and it allows tobacco users to register for telephone counseling, download fact sheets about topics such as nicotine addiction and the health benefits of quitting smoking, and access digital information and local resources for quitting smoking.

Targeting Smoker Proxies with Innovative Media: Health Care Professionals in California

With funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and direction from CTCP, the California Smokers’ Helpline created and implemented a communications campaign each year for three years from October 2009 to September 2012 and targeted health care providers throughout California. Each campaign was designed to increase awareness of Helpline services among health care professionals and encourage them to refer patients to the Helpline. Each campaign began with a clearly defined strategy that guided both the development and implementation of campaign activities. The strategies included campaign goals and objectives, target audience, offers, call-to-action, media channels, and evaluation criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Strategy Summary for Each Year of the Campaign

| 2009–2010 | 2010–2011 | 2011–2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schedule | Oct 2009 to Jun 2010 | Nov 2010 to Sept 2011 | Feb 2012 to Sept 2012 |

| Objectives |

|

|

|

|

Target audience |

|

|

|

|

Call-to- action |

|

|

|

|

Media channels |

|

|

|

|

Evaluation criteria |

|

|

|

Although the long-term goal of each campaign was to increase calls from smokers to the Helpline, there was a focus on proxies to reach smokers. These proxies were health care professionals who were positioned to refer smokers to the Helpline, thus reaching smokers through their interactions. The first two campaigns focused on a general clinician audience (physicians, nurses, and pharmacists) with the Ask, Advise, Refer message, based upon the Helpline’s scope of work with CTCP. The focus on behavioral health professionals in the third campaign was based on demand from Helpline constituents and on the body of evidence about the importance of treating tobacco dependence among smokers with behavioral health issues (Guydish 2011; Baca 2009; Lasser 2000).

Once the target audiences were selected, the campaign objectives, core message, offers, and call-to-action were defined. During the first two campaigns, this information was used by the CTCP to develop ad concepts. The Helpline then worked with an advertising consultant to develop a media plan. In the third campaign, the Helpline provided the campaign strategy to an advertising consultant who developed ad concepts and recommended a media plan.

Each year, the media channels and creative content were evaluated before the launch of campaign activities. An online survey administered by [OMB 0920-0917] was conducted among members of the target audience, including physicians, nurses, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and behavioral health professionals to gauge receptivity to potential creative concepts, and to identify appropriate media channels for reaching them. These data were used to select ad concepts and media channels for each campaign. Data reported during the first and second campaigns were also used to guide the selection of ad concepts and media channels for subsequent campaign years.

The most significant changes in campaign strategies were fueled by a general trend in marketing away from traditional media (print ads and direct mail) and toward online media, such as web banner ads and e-blasts (Frank 2000). Accordingly, the Helpline provider campaigns increasingly relied on the use of digital media, development of compelling online content, and use of more specific metrics.

In the first campaign, ads were concentrated in print channels, including specialty academic journals and professional publications catering to the target audience. Ads were run in six print publications: California Family Physician, California Academy of Physician Assistants News, California Journal of Health-Systems Pharmacists, The Diabetes Educator Journal, New England Journal of Medicine, and NurseWeek. In addition, direct mail was sent to 22,764 members of professional organizations, including the California Academy of Family Physicians, California Primary Care Association, and California Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Mailing lists for the direct mail efforts were obtained from the California Primary Care Association and from some of the academic journals, as part of the media buy. Digital ads were part of the initial campaign activities and appeared on websites and in e-blasts and e-newsletters associated with organizations such as the California Medical Association and California Family Physician. In the second and third campaigns, digital advertising became a larger part of the media mix. The second and third campaigns continued to feature digital ads appearing on websites and in e-blasts and e-newsletters associated with organizations but with greater emphasis than the first campaign. During the 2009–2010 campaign, digital marketing activities were responsible for about 10% of gross advertising impressions*; this increased to about 80% for the 2011–2012 campaign.

METHODS

We describe data from the three campaigns that ran October 2009 – June 2010, November 2010 –September 2011, and February 2012 – September 2012. Process data was increasingly available in the second and third campaign years because of improvements in tracking short-term outcomes during and immediately following each campaign. In addition to the online materials and webinars, print promotional materials were offered throughout each campaign to health care professionals as a resource when referring smokers to the Helpline. Starting in the third campaign year, campaign staff began collecting information on each order so as to track the effectiveness of each campaign in generating orders, particularly from the target audience.

The marketing automation program purchased by campaign staff enabled creation and tracking of landing pages with lead submission forms for specific offers; capture, segmentation, and storage of contact information from lead submission forms; and tracking of sources of all online visitors, including organic search, direct traffic, referrals from other sites, email marketing, and social media. These summary data were provided from various internal and external sources: advertising publications [media impressions and click-through-rates [the number of times a click is made on the advertisement divided by the total impressions], Google Analytics™ web analytics service (web visits), HubSpot™ (downloads of free materials), Adobe Connect™* (webinar registrations), and the Helpline online order form (orders of promotional materials by behavioral health professionals, including those affiliated with mental health and chemical dependency treatment programs).

Campaign summaries were created at the end of each year that described each campaign’s efforts and reported summary tracking data generated over the course of each year. These campaign summaries and source data were used to construct this descriptive case study (Sandelowski, 2000) of the use of online media by the California Smokers’ Helpline to target health care professionals. Challenges and lessons learned from the implementation experiences of campaign staff are highlighted below.

RESULTS

Campaign Responsiveness to the Challenges of Digital Media

Although each campaign strategy was well defined, they were not rigid from one year to the next, as demonstrated by the evolving call-to-action, offers, media channels, and evaluation criteria that changed with each campaign. For example, when implementing the campaigns, staff discovered that digital media were more cost effective than print, with a cost per impression of about $0.07 for digital media, compared to $0.37 for print. This led to the second and third campaign years focusing more on digital media. In addition, metrics for digital media were easily measured by using the sources described previously; however they also posed several challenges. Staff responded to these challenges as they implemented the digital media components of the campaign, resulting in several lessons learned..

Maintaining Interest in Ad Content

With the increased emphasis on digital advertising, it became more important to develop new and compelling online offers to entice viewers to click on the ads. A key challenge was that digital ad performance, measured by using click-through rates, tended to decline over time unless new ad content was used. In the case of a monthly e-blast used during the 2010–2011 campaign, the same digital ad initially performed above industry average click-through-rates of 0.20% to 0.30% (Public Media Interactive, 2012) with a click-through-rate of 0.35%, but the performance gradually declined during the 6-month course of the campaign to a click-through-rate of 0.21%. In response, staff changed the campaign activities to include the ongoing development of new creative content and offers to sustain the click-through-rate throughout the campaign period. As shown from an e-blast that was a part of the 2011–2012 campaign activities, the click-through-rate remained strong (range 0.40% to 0.83%) when the ad content and messages were rotated monthly (Table 2).

Table 2.

Click-Through-Rate for Different E-Blast Ad Creative and Offers Over Time

| Date | Creative | E-blast delivered |

E-blast opened |

E-blast clicks |

CTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2/22/2012 | Option 1 | 3,000 | 329 | 8 | 0.27% |

| 3/22/2012 | Option 2 | 3,000 | 346 | 25 | 0.83% |

| 4/3/2012 | Option 3 | 3,000 | 395 | 13 | 0.43% |

| 5/22/2012 | Option 1 | 3,000 | 332 | 12 | 0.40% |

| 6/20/2012 | Option 2 | 3,000 | 334 | 12 | 0.40% |

Starting with the 2011–2012 campaign, a series of webinars and online materials were also offered during the campaign to keep it fresh, compelling and relevant to the target audience.

Monitoring Proxy-Targeted Campaigns

One characteristic of proxy-targeted campaigns (like the one described here) is that it may take more time for campaign activities to affect the outcomes of interest. Unlike advertising directly to consumers, reaching out to health care providers to refer patients to the Helpline is indirect and may take more time before any resulting changes in call volume are realized. Furthermore, although general referral sources are tracked during Helpline caller intake, specific sources are not, making it difficult to link calls to a specific campaign.

Because of the challenges of relating consumer calls to specific media campaigns, short-term indicators were monitored during each campaign. These non-call volume metrics initially focused on general measures, such as media impressions and website visits, and evolved over time to more specific measures such as the number of downloads, website visits, digital ad click-through-rates, webinar registrations, orders for materials, and other actions that could be readily measured.

The campaigns resulted in more than 2.7 million gross impressions from digital media sources during three years. In 2011, a marketing automation program was purchased that allowed for the creation of unique landing pages with lead (or contact) capture forms for each offer of online information. In turn, these landing pages were linked to specific ads associated with each media channel (i.e., print, web, email, direct mail). This linking enabled easier and more accurate tracking of the number of new leads or contacts acquired throughout the 2011–2012 campaign and better assessment of the cost-effectiveness of each media channel. With marketing automation, measurement of campaign success shifted from general tracking metrics to more specific short-term outcomes, such as the number of new contacts acquired (n=901). As a result, staff collected data throughout the 2011–2012 campaign.

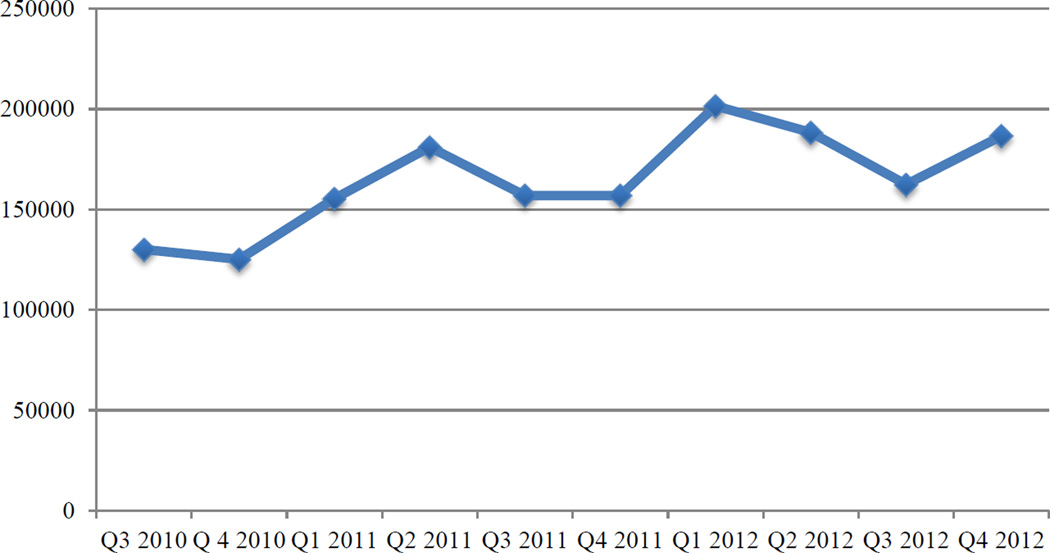

In addition to the online materials and webinars, print promotional materials were offered throughout each campaign to health care professionals as a resource when referring smokers to the Helpline. Campaign staff began collecting information on each order to track the effectiveness of each campaign in generating new orders. As shown here (Figure 1), orders steadily increased after the first campaign in 2010–2011. During the ordering process, data were gathered on the type of organization represented by each individual who ordered materials, which allowed assessment of campaign response by type of health care professional.

Figure 1.

Orders of Helpline Promotional Materials Over Time

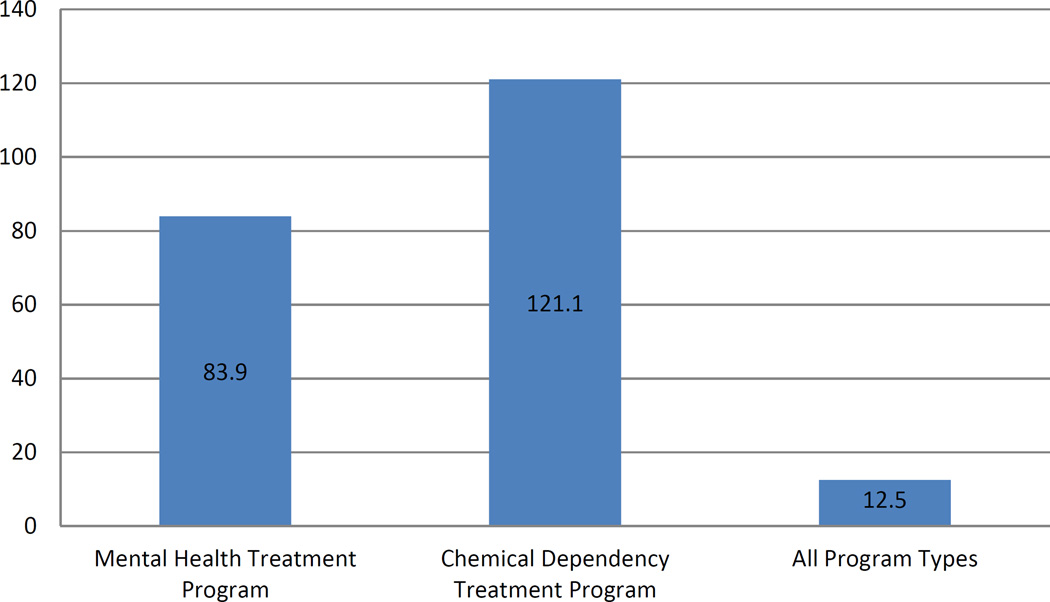

Tracking data were also adjusted to match the new activities developed for the target audience in the 2011–2012 campaign. Because the focus shifted to a specific type of health care professional, criteria such as number of orders for promotional materials by behavioral health professionals affiliated with chemical dependency or mental health treatment programs were better indicators of response among the targeted subgroup. This refinement in focus and corresponding adjustment in tracking data show that the 2011–12 campaign was particularly successful in reaching its target audience (Table 3).

Table 3.

Promotional Material Orders by Behavioral Health Professionals in 2011 and 2012

| Orders Placed | Mental health treatment program |

Chemical dependency treatment program |

All Program Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 31 | 19 | 949 |

| 2012 | 57 | 42 | 1,068 |

| % Increase between 2011 and 2012 | 83.9 | 121.1 | 12.5 |

Orders for promotional materials by behavioral health professionals affiliated with mental health treatment programs increased by 83.9% from 2011 to 2012, while those by behavioral health professionals affiliated with chemical dependency treatment programs increased by 121.1%. These increases were several times larger than the overall increase in orders between these two time periods (12.5%) and would have been difficult to identify without specifically tailored metrics.

DISCUSSION

Each campaign’s clearly defined strategy proved essential for establishing activities at the outset and for guiding adjustments and improvements in response to challenges during the campaigns. Although the overall objectives were the same, some aspects varied from year to year as the campaigns evolved and incorporated lessons learned from previous years. Staff found that ease of ongoing monitoring is one of the benefits to using digital media and allows programs to be responsive to short-term campaign outcomes. If these metrics are readily available, the campaign components can be adjusted on the basis of which activities prove most effective.

There were also many lessons learned in regard to the heavy reliance on digital media. First, digital marketing vehicles vary widely among publications, but lower cost and ease of measurement increase the desirability of digital media channels over print. However, this may also require more investment in developing visually appealing and engaging educational content, such as online kits, videos, podcasts, webinars, and tip sheets.

Second, target audiences do not prefer all media channels equally. To make the most cost-effective use of media budgets, campaign staff could research and select media channels carefully on the basis of the target audience’s preferences. Third, frequent rotation of new ad content helps to keep the target audience engaged, especially with digital media. This highlights the need to develop and test a variety of ad content for rotation.

Fourth, program staff might want to consider hiring a consultant with experience developing digital ad content and buying digital media. This might be especially helpful if program staff are not experienced with digital advertising as it continues to evolve at a fast pace and requires a specific skill set. While hiring a consultant is an additional expense, working collaboratively with digital media experts may be more efficient than spending resources for campaign staff to gain expertise in digital media.

Fifth, campaign staff could develop a clear strategy that includes a definition of the target audience, goals and objectives, call-to-action, media channels, offers, and evaluation criteria. Clear, consistent, specific, and measurable evaluation criteria, such as the number of downloads, website visits, webinar registrants, orders of materials, and other actions that can be easily measured, is important.

Sixth, it is important to identify the appropriate metrics and data sources to measure the response to campaign activities. This step might be particularly challenging for proxy-targeted campaigns. For quitline campaigns, self-reported referral sources during quitline intake calls might be necessary to link campaigns to changes in quitline call volume. The number of consumer calls referred by specific target audiences might also be used as an evaluation measure. In the case of proxy-targeted campaigns, informative non-call volume metrics (e.g., the number of materials downloaded, print materials ordered, and webinar registrations) might be necessary to measure the full impact of the campaign.

Finally, it might be advantageous to purchase a marketing automation program that captures contact information, tracks many key metrics in one place, and improves the ability to quantify and measure progress toward specific campaign goals. Programs with limited resources may want to consider the cost-effectiveness of investing in this type of program. If equivalent or greater resources are spent tracking key metrics using other means, such a program might be worthy of investment.

On the basis of these experiences, campaign staff suggested several refinements to campaign activities to be considered for future years that can be used to inform similar efforts. Google Analytics™ web analytics data show that search engines were an important factor in connecting smokers to the Helpline. In response, campaign staff identified a long-term goal of redesigning the Helpline website to increase search engine optimization and improve the visitors’ experiences. In addition, they are considering technical upgrades to other programs to improve data capture and the ability to quantify campaign goals. These upgrades include the development of an e-commerce website for processing orders of Helpline print promotional materials, the purchase of a new webinar program, and the purchase of a customer relationship management program. The goal of these improvements is to collect and integrate additional data with the marketing automation program, which will allow better capture and follow-up with new contacts, and improved assessment the effects of advertising and promotional efforts targeted to health care providers.

While further research is necessary to determine if the experiences of the California Smokers’ Helpline campaign staff are generalizable to other campaigns, given limited comparative studies, these lessons learned may prove valuable to similar efforts. Strategic data collection and monitoring is necessary to enable programs to evaluate their activities and build on these experiences. These data are necessary to construct an evidence base to advance our understanding of how best to use limited resources to maximize the positive impact of digital media health campaigns.

LIMITATIONS

There are no data linking call volume to campaign activities, precluding a direct evaluation of the campaign’s effectiveness in increasing calls to the California Smokers’ Helpline. The case study presented in this article is drawn from the experiences of the CTCP and Helpline media campaigns and are limited to this particular case. Although the conclusions from this study may not generalize to all uses of digital advertising in similar health promotion efforts, they may help guide the planning and development of such efforts. Limited scientific literature has studied the use of new media in health promotion, highlighting the need for sharing experiences from similar campaigns to those described here.

Figure 2.

Percent Increase in Promotional Material Orders by Behavioral Health Professionals in 2011 and 2012

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) through the Office of the Secretary Award No. 200-2008-27958, Task Order 0014 via a contract from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to RTI International.

Footnotes

Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This term denotes the number of instances that an advertisement has been viewed.

Contributor Information

Youn Ok Lee, RTI International.

Behnoosh Momin, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Heather Hansen, RTI International.

Jennifer Duke, RTI International.

Kristin Harms, California Smokers’ Helpline, University of California, San Diego.

Amanda McCartney, California Tobacco Control Program, California Department of Public Health.

Antonio Neri, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Jennifer Kahende, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Lei Zhang, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sherri L. Stewart, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- Baca CT, Yahne CE. Smoking cessation during substance abuse treatment: what you need to know. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36(2):205–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendryen H, Kraft P. Happy Ending: A randomized controlled trial of a digital multi-media smoking cessation intervention. Addiction. 2008;103:478–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockman TA, Patten CA, Smith CM, Hughes, C.A, Sinicrope PS, Bonnema SM, Decker PA. Process of counseling support persons to promote smoker treatment utilization. Addiction Research & Theory. 2012;20(6):466–479. [Google Scholar]

- Cline RJW, Haynes KM. Consumer health information seeking on the Internet: The state of the art. Health Education Research. 2001;16:671–692. doi: 10.1093/her/16.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. Pew Pew Internet & American Life Project. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2005. May 17, [Retrieved February 26, 2013]. Health Information Online. (2005). from http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media/Files/Reports/2005/PIP_Healthtopics_May05.pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Fox S, Duggan M. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2013. Jan 15, [Retrieved January 27, 2013]. Health Online 2013. (2013). from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Health-online/Summary-of-Findings.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Frank SR. Digital health care—the convergence of health care and the Internet. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2000;23(2):8–17. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200004000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Passalacqua E, Tajima B, Chan M, Chun J, Bostrom A. Smoking prevalence in addiction treatment: a review. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 13(6):401–411. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japuntich SJ, Zehner ME, Smith SS, Jorenby DE, Valdez JA, Fiore MC, Baker TB, Gustafson DH. Smoking cessation via the Internet: A randomized clinical trial of an internet intervention as adjuvant treatment in a smoking cessation intervention. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006 Dec;8(Suppl 1):S59–S67. doi: 10.1080/14622200601047900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl LF, Crutzen R, de Vries NK. Online prevention aimed at lifestyle behaviors: a systematic review of reviews. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15(7):e146. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and Mental Illness. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(20):2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClave AK, McKnight-Eily LR, Davis SP, Dube SR. Smoking characteristics of adults with selected lifetime mental illnesses: Results from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(12):2464–2472. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North American Quitline Consortium. U.S. Quitlines: Internet-Based Services. [March 20, 2013];FY2011 NAQC Annual Survey of Quitlines. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.naquitline.org/resource/resmgr/2011_survey/fy11_usa_internet_based_serv.xls. [Google Scholar]

- Public Media Interactive (PMI) Measuring Performance: What is a Good Clickthrough Rate (CTR)? [Blogpost] [March 20, 2013];2012 Feb 28; Retrieved from http://publicmediainteractive.org/2012/02/28/measuring-performance-what-is-a-good-clickthrough-rate-ctr/ [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Focus on Research Methods. Whatever Happened to Qualitative Description? Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecher VJ. Computer-tailored smoking cessation materials: A review and discussion. Patient Education and Counseling. 1999;36:107–117. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Wright JA, Shegog R. A review of computer and Internet-based interventions for smoking behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:264–277. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SH, Nguyen QB, Cummins S, Wong S, Wightman V. Non-smokers seeking help for smokers: a preliminary study. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(2):107–113. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]