Abstract

Background

Keratoconus may progress to acute corneal hydrops even after cross-linking. In some cases, keratoconus progresses during pregnancy. In this report, we present a case of a patient with increased anterior stromal resistance after cross-linking that would favor nonprogression of keratoconus during pregnancy.

Case presentation

We report that cross-linking is likely to have had a protective effect in a white pregnant patient with acute corneal hydrops who showed rapid improvement, as documented by corneal topography. Improvement occurred within 8 days, whereas up to 250 days are reported in the literature. No keratoconus progression occurred in the 20-month follow-up period.

Conclusions

Cross-linking failed to prevent the occurrence of acute corneal hydrops after rupture of Descemet’s membrane but most likely helped to accelerate the resolution of the condition. Corneal hardening resulting from cross-linking may have also contributed to stabilizing keratoconus during pregnancy.

Keywords: Cornea, Keratoconus, Corneal edema, Corneal opacity, Corneal topography

Background

Keratoconus is a multifactorial, noninflammatory degeneration of the cornea that causes a loss of stability. It is clinically characterized by central thinning of the cornea and irregular astigmatism, which reduce visual acuity (VA). The treatment for keratoconus depends on its severity, and corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL) is an excellent treatment option in cases of disease progression [1]. We report a case of a pregnant patient who progressed to acute corneal hydrops after completing CXL treatment with an unusual resolution that occurred in 8 days without scarring. Resolution normally occurs within 5 to 36 weeks with scarring [2].

Case presentation

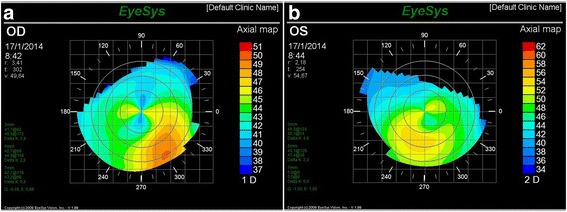

A 26-year-old white woman without systemic disease presented with bilateral progressive keratoconus, showing best-corrected VAs of 20/30 and 20/40 in the right eye (RE) and left eye (LE), respectively. Corneal topography showed maximum corneal curvatures of 49.64 and 54.67 diopters in the RE and LE, respectively (Fig. 1a and b), with central corneal thicknesses measured by ultrasonic pachymetry of 471 and 484 μm for the RE and LE, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative corneal topography RE (a) and LE (b)

The patient was subjected to standard protocol CXL in both eyes and showed best-corrected VAs of 20/30 and 20/40 in the RE and LE, respectively, 3 months after the procedure. Biomicroscopy showed a demarcation line in the anterior stroma without haze.

The patient began using rigid contact lenses (RCLs) 5 months after the procedure and reached a VA of 20/20. The patient returned complaining of pain, photophobia, and low VA in her LE 7 months after undergoing CXL, when she mentioned her 5-month pregnancy.

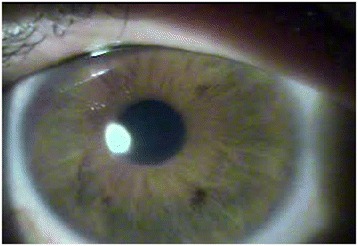

LE biomicroscopy showed a clinical condition of acute corneal hydrops, with Descemet’s membrane rupture in the central area, approximately 2 mm horizontally and 4 mm vertically, and associated stromal edema, with no signs of inflammation in the anterior chamber (Fig. 2). Her VA was 20/500 without correction in the LE and 20/20 in the RE with an RCL. The RE was normal, with a well-adjusted RCL. Treatment with antibiotic eye drops and associated corticosteroids was initiated, and the patient returned 1 week later with no complaints about the LE and showing complete resolution of the corneal hydrops (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Descemet’s membrane rupture

Fig. 3.

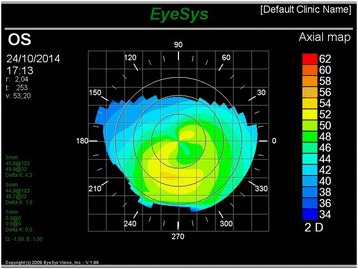

Complete resolution of the condition

LE corneal topography showed flattening of the maximum corneal curvature from 54.7 diopters to 53.20 diopters (Fig. 4). The patient showed a VA of 20/20 in both eyes with RCLs.

Fig. 4.

Left eye corneal topography showing resolution of the condition

Discussion

Hormonal effects, which remain poorly understood, are among the factors involved in keratoconus. Studies [3, 4] have shown that estradiol stimulates the production of matrix metalloproteinases and the production or activation of collagenolytic enzymes, which may be responsible for collagen weakening. Furthermore, estrogen increases the release of prostaglandins and activates collagenase. These events cause collagen degradation and therefore decreased corneal rigidity [3]. Thus, hormonal factors are related to the onset of keratoconus, and increased estrogen (which occurs during pregnancy) is related to its progression [4]. This case was followed for 9 months after performing CXL, and the lack of keratoconus progression during pregnancy was confirmed by corneal topography.

One of the most common complications of keratoconus is acute corneal hydrops, which is typically corneal edema resulting from the rupture of Descemet’s membrane and endothelium [5]. Continuous intrastromal buildup of aqueous humor causes the separation of collagen lamellae and formation of fluid-filled clefts/cysts [6]. The adjacent endothelium becomes hypertrophied in the area of rupture of Descemet’s membrane and determines the duration of resolution of the condition (within 5 to 36 weeks) [2].

In this study, the complete resolution of the patient’s acute corneal hydrops occurred in only 8 days. This resolution may have resulted from prior CXL, which promoted a photochemical reaction generating free radicals and oxygen radicals [7]. The free radicals catalyze the reaction and form covalent bonds between collagen molecules and microfibers [8] that stabilize the stroma and improve collagen structure, thereby hindering the formation and persistence of corneal stromal edema [7]. Furthermore, the biomechanical effect is related to an increase in corneal rigidity of approximately 328.9% [9]. Surprisingly, the patient progressed without haze and with 20/20 VA with RCLs, which was confirmed by a slit-lamp evaluation and the Snellen test.

Conclusions

The present case led us to the hypothesis that CXL increases anterior stromal resistance through covalent bonds between collagen fibers. This increase in anterior stromal resistance would obstruct the passage of aqueous humor after rupture of Descemet’s membrane. Furthermore, increased corneal hardening would favor keratoconus nonprogression during pregnancy. However, other studies are necessary to determine whether CXL accelerates the resolution of acute corneal hydrops.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Bruno Fontes, from Brazil.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The author’s original image files are available within the article.

Authors’ contributions

RS was involved in the ophthalmic management of the patient and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. TT carried out literature research. ELB contributed to the review and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- CXL

Collagen cross-linking

- LE

Left eye

- RCL

Rigid contact lens

- RE

Right eye

- VA

Visual acuity

Contributor Information

Ricardo Alexandre Stock, Email: ricardostockreal@gmail.com.

Thaís Thumé, Email: thais_thume@hotmail.com.

Elcio Luiz Bonamigo, Email: elcio.bonamigo@unoesc.edu.br.

References

- 1.Suri K, Hammersmith KM, Nagra PK. Corneal collagen cross-linking: ectasia and beyond. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:280–5. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e328354865e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma N, Maharana PK, Jhanji V, Vajpayee RB. Management of acute corneal hydrops in ectatic corneal disorders. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:317–23. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e328354a2a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spoerl E, Zubaty V, Raiskup-Wolf F, Pillunat LE. Oestrogen-induced changes in biomechanics in the cornea as a possible reason for keratectasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1547–50. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.124388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki T, Kinoshita Y, Tachibana M, Matsushima Y, Kobayashi Y, Adachi W, Sotozono C, Kinoshita S. Expression of sex steroid hormone receptors in human cornea. Curr Eye Res. 2001;22:28–33. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.22.1.28.6980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan Gaskin JC, Patel DV, McGhee CN. Acute corneal hydrops in keratoconus - new perspectives. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:921–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maharana PK, Sharma N, Vajpayee RB. Acute corneal hydrops in keratoconus. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61:461–4. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.116062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raiskup F, Theuring A, Pillunat LE, Spoerl E. Corneal collagen crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A light in progressive keratoconus: ten-year results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan E, Snibson GR. Current status of corneal collagen cross-linking for keratoconus: a review. Clin Exp Optom. 2013;96:155–64. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wollensak G. Crosslinking treatment of progressive keratoconus: new hope. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:356–60. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000233954.86723.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The author’s original image files are available within the article.