Abstract

Small specimen volume and high sample throughput are key features needed for routine methods used for population biomonitoring. We modified our routine 8-probe solid phase extraction (SPE) LC-MS/MS method for the measurement of five folate vitamers (5-methyltetrahydrofolate [5-methylTHF], folic acid [FA], plus three minor forms: THF, 5-formylTHF, 5,10-methenylTHF) and one oxidation product of 5-methylTHF (MeFox) to require less serum volume (150 μL instead of 275 μL) by using 96-well SPE plates with 50-mg instead of 100-mg phenyl sorbent and to provide faster throughput by using a 96-probe SPE system. Total imprecision (10 days, 2 replicates/day) for three serum quality control (QC) pools was 2.8–3.6% for 5-methylTHF (19.5–51.1 nmol/L), 6.6–8.7% for FA (0.72–11.4 nmol/L), and ≤11.4% for the minor folate forms (<1–5 nmol/L). Mean (±SE) recovery of folates spiked into serum (3 days, 4 levels, 2 replicates/level) was: 5-methylTHF, 99.4±3.6%; FA, 100±1.8%; minor folates, 91.7–108%); SPE extraction efficiencies were ≥85% except for THF (78%). Limits of detection were ≤0.3 nmol/L. The new method correlated well with our routine method (n=150; r=0.99 for 5-methylTHF, FA, and total folate [tFOL, sum of folate forms]) and produced slightly higher tFOL (5.6%) and 5-methylTHF (7.3%) concentrations, likely due to the faster 96-probe SPE process (1 vs. 5 h) resulting in improved SPE efficiency and recovery compared to the 8-probe SPE method. With this improved LC-MS/MS method, 96 samples can be processed in ~2 h and all relevant folate forms can be accurately measured using a small serum volume.

Keywords: automated solid phase extraction, MeFox, hmTHF, method comparison, microbiologic assay, anticoagulant types

Introduction

Serum folate is an important marker of short-term folate status and has been used for 25 years to monitor changes in the US population through the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from before the introduction of folic acid fortification (NHANES 1988–1994) to post-fortification (NHANES 1999–2012). The NHANES collects cross-sectional data on the health and nutritional status of the civilian non-institutionalized US population and has been conducted as a continuous survey with data released every two years since 1999. Up to 2006, the Bio-Rad QuantaPhase II radioassay was used to measure blood folate concentrations and after the manufacturer discontinued the assay, the microbiologic assay (MA) was used from 2007–2010. Both of these assays measured total folate (tFOL). In 2010, an expert roundtable advised CDC on folate biomarkers and methods for future NHANES surveys [1]. Because in the era of post-fortification, public health concerns are no longer limited to low folic acid intakes, but extend to the safety of high intakes, which are largely driven by supplement use [2], the roundtable advised NHANES to use a liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method in 2011–2012 [1]. This allows for the measurement of individual folate vitamers, including unmetabolized folic acid (FA), and calculation of tFOL by summation of the individual vitamers. We have previously shown good correspondence between the LC-MS/MS determined tFOL and the tFOL determined by the MA (on average ~6% lower) [1, 3], the latter assay being considered a “gold standard” because it measures all biologically active forms of folate nearly equally and does not measure degradation products that lack biological activity [4]. However, we have also shown that depending on the calibrator and microorganism used, the MA may produce different folate results [5].

Since we developed an automated 8-probe solid phase extraction (SPE) isotope-dilution LC-MS/MS method for five folate vitamers in serum and whole blood about 10 years ago [6, 7], we applied this method to various research studies, including the measurement of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-methylTHF) and FA in a 1/3 subset of serum samples from NHANES 2007–2008. More recently, we modified the LC-MS/MS portion of the method to include measurement of an oxidation product of 5-methylTHF known as MeFox (pyrazino-s-triazine derivative of 4α-hydroxy-5-methylTHF) [8]. This method is currently used to measure serum folate forms in NHANES 2011–2012.

The sample volume requirement for the current LC-MS/MS method is 275 μL serum per test and the throughput is limited to 76 samples per run as the 8-probe automated SPE process takes ~5 h. However, the NHANES sample volume is limited (≤ 700 μL) and fast turnaround (< 3 weeks) is needed as folate results are reported to participants typically within a month of blood collection. Thus, our primary objective was to further improve the routine LC-MS/MS method to make it highly suitable for large population biomonitoring studies: scale down the SPE procedure so that it requires a smaller sample volume and increase the sample throughput. Our secondary objective was to validate this new method and assess how it compares to the current routine method as well as to the MA, in order to provide continuity for assessing long-term folate trends in NHANES.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, reagents, and specimens

All folate monoglutamate standards (5-methylTHF, FA, tetrahydrofolate [THF], 5-formyltetrahydrofolate [5-formylTHF], 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate [5,10-methenylTHF]) and MeFox together with their stable-isotope 13C5-labeled analogues (used as internal standards) were purchased from Merck, Cie (Schaffhausen, Switzerland). Folate stock solutions were prepared as described earlier and concentrations were assigned spectrophotometrically using published extinction coefficients [6–8]. Other reagents and solvents were of ACS reagent grade unless stated otherwise. Purified water (18 MΩ) from an Aqua Solutions water purification system was used to prepare all samples, calibrators and reagents. All sample handling was performed under gold-fluorescent light. Low, medium, and high quality control (QC) pools were prepared in-house from pooled human serum obtained from anonymous blood donors (Tennessee Blood Services, Memphis, TN). Units of serum were screened for folate forms, and as needed, spikes of folate calibrators were added to the blended pooled materials to achieve different concentrations. L-ascorbic acid (5 g/L) was added to each pool to enhance long-term stability of folate forms. All specimens were stored at −70 °C when not in use.

Sample preparation and analysis by LC-MS/MS

Descriptions of sample preparation steps for the routine 8-probe (method 1), scaled down 8-probe (method 2), and scaled down 96-probe (method 3) SPE methods are presented in Table 1. We prepared a fresh mixed working calibrator containing 5-methylTHF, FA, THF, 5-formylTHF, 5,10-methenylTHF, and MeFox (5-methylTHF 2.0 μmoL/L, all other folate forms 1.0 μmoL/L) in 1 g/L ascorbic acid for each run from individual frozen stock solutions [6–8]. From this mixed calibrator, a six-point calibration curve was prepared in SPE sample buffer (10 g/L ammonium formate containing 5 g/L ascorbic acid, pH 3.2) corresponding to 0–100 nmoL/L for 5-methylTHF and 0–50 nmoL/L for all other folate forms. We also processed a reagent blank with each run. We prepared a fresh mixed solution of all internal standards in 1 g/L ascorbic acid (200 nmoL/L for 13C5-5-methylTHF and 50 nmoL/L for all other labeled folates) for each run from individual frozen stock solutions (corresponding to a concentration of 6.0 nmol/L 13C5-5-methylTHF and 1.5 nmol/L for all other labeled folates for methods 2 and 3). The LC-MS/MS analysis conditions are described in Table 1 and MS/MS instrument settings for each folate form are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Quantitation was based on peak area ratios between the analyte and internal standard interpolated against the six-point linear calibration curve (no weighting). Evaluation of quadratic and cubic curve fits produced non-significant x2 and x3 coefficients for each folate form. The aqueous calibration curve was reinjected at the end of each run to assess potential calibrator drift. Each run included three serum QC samples measured in duplicate, bracketing the unknown samples. A multi-rule QC program [9] based on rules similar to Westgard 1 3S, 2 2S, 10 Xbar and R 4S rules was used to determine whether runs were in control.

Table 1.

Sample preparation and analysis steps for three LC-MS/MS methods measuring serum folate forms

| Step | Method 1: Routine 8-probe SPE | Method 2: Scaled down 8-probe SPE | Method 3: Scaled down 96-probe SPE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Preparation of buffered calibrators (in 2-mL 96-deep well plates; Whatman, Fisher Scientific) |

275 μL mixed calibrators1–6 | 150 μL mixed calibrators 1–6 | 150 μL mixed calibrators 1–6 |

| 495 μL sample buffera | 220 μL sample buffer | 220 μL sample buffer | |

| 275 μL deionized water | 150 μL deionized water | 150 μL deionized water | |

| 55 μL mixed internal standards | 30 μL mixed internal standards | 30 μL mixed internal stand | |

|

| |||

| 2. Preparation of buffered serum samples (QC or unknown samples; in 2-mL 96-deep well plates) |

275 μL serum | 150 μL serum | 150 μL serum |

| 770 μL sample buffer | 370 μL sample buffer | 370 μL sample buffer | |

| 55 μL mixed internal standards | 30 μL mixed internal standards | 30 μL mixed internal standards | |

|

| |||

| 3. Incubation (5 °C, 20 min) | To allow for equilibration of labeled internal standards with unlabeled endogenous folates | ||

|

| |||

| 4. SPE sample clean-up | |||

| Automated system | 8-probe Gilson-215, Gilson Inc. | 8-probe Gilson-215, Gilson Inc. | 96-probe Caliper Zephyr, Perkin Elmer |

| 96-well plates | 100-mg phenyl sorbent (Bond Elut, Agilent Technologies) |

50-mg phenyl sorbent (Bond Elut, Agilent Technologies) |

50-mg phenyl sorbent (Bond Elut, Agilent Technologies) |

| Conditioning | 1.0 mL acetonitrile | 500 μL acetonitrile | 500 μL acetonitrile |

| 1.0 mL methanol | 500 μL methanol | 500 μL methanol | |

| 1.5 mL bufferb | 1.0 mL buffer | 1.1 mL buffer (2 steps) | |

| Sample loading | 1.0 mL sample | 500 μL sample | 500 μL sample (2 steps) |

| Washing | 3.0 mL wash bufferc (2 steps) | 1.6 mL wash buffer (2 steps) | 1.35 mL wash buffer (3 steps) |

| Sample elution | 1 mL elution bufferd | 500 μL elution buffer (2 steps) | 500 μL elution buffer (2 steps) |

|

| |||

| 5. Sample filtration | Under vacuum using 96-well plate PVDF filters (Captiva, Agilent Technologies); if not analyzed immediately, samples were stored at −70 °C until analysis by LC-MS/MS |

||

|

| |||

| 6. LC-MS/MS analysis | HPLC system: | ||

| HP1200 LC (Agilent Technologies) (binary pump [600 bar pressure], thermostatted autosampler maintained at 10 °C, in-line mobile phase degasser, column oven maintained at 30 °C) |

|||

| Luna C8(2) HPLC column (150 × 3 mm, 5 μm) (Phenomenex) | |||

| Isocratic mobile phase (water 49.5%:methanol 40%:acetonitrile 10%:acetic acid 0.5% [v/v/v/v]) | |||

| Flow rate: 250 μL/min | |||

| Injection volume: 20 μL | |||

| Run time: 7 min (column effluent directed to mass spectrometer from 1.0–5.0 min, otherwise to waste) | |||

| 96-well HPLC plates (33 mm) sealed with pre-slit plate seals (Nunc, Fisher Scientific) | |||

| Tandem mass spectrometer: | |||

| API5500 triple quadrupole MS system (AB Sciex) | |||

| Positive ion mode electrospray ionization (TurboIonSpray™) | |||

| Nitrogen used as curtain, source, and collision gas | |||

| Analyst software version 1.5.1 used to control system, acquire and process data | |||

Sample buffer: 10 g/L ammonium formate containing 5 g/L ascorbic acid, pH 3.2

Buffer: 10 g/L ammonium formate, pH 3.2

Wash buffer: 0.5 g/L ammonium formate containing 2 g/L ascorbic acid

Elution buffer: 49% water (containing 5 g/L ascorbic acid):40% methanol:10% acetonitrile:1% acetic acid (v/v/v/v)

Method validation

The FDA ”Bioanalytical Method Validation” document [10] and our Division’s “Policies and Procedures Manual for Bioanalytical Measurements” provided guidance for method validation experiments. All experiments for methods 2 and 3 were carried out in parallel (same day) using the same calibration and internal standard solutions. We evaluated calibrator accuracy for 10 runs by calculating the mean percent difference between the measured and nominal calibrator value (two replicates per run). Method imprecision, accuracy and sensitivity were determined for methods 2 and 3 using serum QC pools. We analyzed three levels of QC pools in 10 runs (two replicates per run) and calculated the total, within- and between-run coefficient of variation (CV). We assessed method accuracy through spike recovery. We spiked the low serum QC pool with a calibrator mixture containing each folate form at four levels (three runs; two replicates per level; 2, 4, 10, and 100 nmol/L spike for 5-methylTHF; 1, 2, 10, and 50 nmol/L spike for all other folate forms) and also measured the QC pool unspiked (three runs, two replicates each) for endogenous folate concentrations (5-methylTHF 19.5, FA 0.67, THF 0.44, 5-formylTHF < LOD, 5,10-methenylTHF < LOD, MeFox 1.34 nmol/L). To assess spike recovery, we added the mixture of internal standards at the same time the spike was added to the sample. To assess SPE efficiency, we added the mixture of internal standards after SPE was completed. The spike recovery and SPE efficiency were calculated as the measured concentration difference between the spiked and unspiked sample divided by the nominal concentration of the spike.

To additionally assess method accuracy, we used serum standard reference materials (SRM) from the US National Institute of Standards Technology (NIST; SRM 1955 [11]: levels 1, 2 and 3; SRM 1950 [12]: one level) and from the United Kingdom National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC; 03/178 [13]: one level). We measured NIST and NIBSC materials in replicates over multiple runs with method 2 (total n = 6) and method 3 (total n = 12) and compared the results to those obtained with method 1 (total n = 10 measured over the course of a year) and to 5-methylTHF certified concentrations reported in the Certificate. For the two NIST materials, we calculated the expanded uncertainty (capturing the uncertainty of our method plus that of the certificate value) for 5-methylTHF according to the formula u = 2 × square root [(SD^2/n) + (U/2)^2], with SD being the standard deviation obtained from the multiple measurements n and U being the expanded uncertainty reported by NIST on the Certificate of Analysis. For the NIBSC material, we calculated the CV (mean divided by SD, expressed as percent) instead, as that is the measure of variation reported in the Certificate.

To determine method sensitivity, we estimated the limit of detection (LOD) for each analyte by serially diluting the medium QC pool with 0.1% ascorbic acid and calculating the SD at a concentration of zero (σ0) from an extrapolation of repeat analyte measurements (three replicates per dilution, three runs) made near the detection limit in these dilutions [14]. The LOD was defined as 3 σ0 and the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) as 10 σ0. We determined the linear dynamic range by analyzing aqueous calibration curves for each folate form in the range of 0–200 nmol/L. We assessed whether aqueous and matrix-based calibration curves produce equivalent results by analyzing three independent preparations of each 10-point calibration curve (0–200 nmol/L range) and comparing the slopes of the linear regression lines. Slopes that agreed within ± 5% were considered to be equivalent.

Effect of specimen type and anticoagulant

To study the effect of different anticoagulants, we used matched serum and plasma specimens from 12 anonymous blood donors (serum, serum separator, K2 EDTA plasma, Na heparin plasma, Na citrate plasma [5-mL blood collection tube with 0.5 mL anticoagulant]; Tennessee Blood Services). Plasma was obtained within 2–4 h of blood collection (blood held at room temperature), serum after overnight clotting (leading to higher serum yield and less residual fibrinogen clots) at room temperature through centrifugation at 4 °C, following standard operating procedures. Specimens were refrigerated, shipped on cold packs, and frozen at −70 °C within 48 h of blood collection. The suitability of plasma as a specimen type compared to serum as the reference was evaluated for tFOL (sum of all measured folate forms) and the three major folate forms 5-methylTHF, FA, and MeFox. Because plasma from the citrate blood collection tube was diluted by 10%, we multiplied results for this specimen type by 1.1.

Method comparison studies

We performed a three-way LC-MS/MS cross-over study using randomly selected pristine serum specimens (n = 150) from a large CDC study to compare methods 2 and 3 to method 1 (reference) for tFOL and each folate form. We analyzed a separate pristine aliquot of the same serum specimens by MA and compared the tFOLMA (reference) to the tFOLwithout MeFox calculated for each of the three LC-MS/MS methods by leaving MeFox out from the summation because the MA does not respond to biologically inactive folate forms. Study participants provided informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the CDC Research Ethics Review Board.

Statistical analysis

We used Analyse-it for Microsoft Excel software version 2.20 (Analyse-it Software Ltd, Leeds, U.K.) to evaluate the specimen type and method comparison data using descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation, Deming regression (because of error in both variables), and Bland-Altman analysis. Because the SD increased over the range of folate concentrations, we used weighted Deming regression (variance ratio was assumed to be 1) and presented Bland-Altman plots as a percent of the mean. We calculated the mean ± SD concentration for each folate form, except when the proportion of results < LOD exceeded 40%, in which case we calculated the median and interquartile range (IQR). We calculated the LC-MS/MS tFOL as the sum of the individual folate forms, using an imputed value of LOD divided by square root of 2 for a folate form result < LOD. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results and discussion

We first modified method 1 to require less specimen volume (150 instead of 275 μL serum) by using 96-well SPE plates with smaller bed volume (50-mg instead of 100-mg phenyl sorbent), but maintaining the same percent composition of sample, solvents, and internal standards as in the routine SPE protocol. This modification makes it possible to reanalyze a sample from a specimen volume ≥ 500-μL in case of a quality control failure or the need to confirm a low or high concentration. The 150-μL test volume is lower compared to most published multi-analyte folate LC-MS/MS methods, which require anywhere from 200 μL to 2 mL of serum or plasma [15–19]. The method by Hannisdal et al. requires only 60 μL of serum [20], however using such a low specimen volume may come at the cost of not being able to detect minor folate forms because of inadequate analytical sensitivity.

To speed up sample throughput, we transferred the SPE procedure from the automated 8-probe Gilson-215 SPE system, which uses positive pressure and takes 25 min for one row of 8 samples, to the automated 96-probe Caliper Zephyr SPE system, which uses negative pressure controlled by a vacuum manifold. This SPE process takes only 1 h for 96 samples (compared to about 5 h for 76 samples using the 8-probe SPE); thus, if needed, we could process two 96-well plates per day, which amounts to about 160 unknown samples.

We verified and confirmed that calibration in water produces equivalent results to calibration in serum for method 3. Slopes for the two calibration curves (serum vs. water) were < ± 5% different for all folate forms (5-methylTHF 4.4%, FA 3.1%, THF −2.6%, 5-formylTHF 4.4%, 5,10-methenylTHF −1.1%, and MeFox 1.8%). We have previously shown that matrix equivalency was also obtained for the routine 8-probe SPE method [6]. Because our methods are based on isotope-dilution mass spectrometry, this is not surprising; it is expected that any matrix effect on the analyte should be the same as for the isotopically labeled internal standard and since the ratio of the two is used for calibration, a potential matrix effect should cancel out. The aqueous calibration curves showed linearity for each folate form over two orders of magnitude (0–200 nmol/L): 5-methylTHF (slope: 0.0246, intercept: 0.0052, r2: 0.9999); FA (slope: 0.1041, intercept: 0.0169, r2: 0.9997); THF (slope: 0.1220, intercept: −0.0285, r2: 0.9995); 5-formylTHF (slope: 0.0843, intercept: −0.0104, r2: 0.9998); 5,10-methenylTHF (slope: 0.1157, intercept: 0.0693, r2: 0.9977); and MeFox (slope: 0.0966, intercept: 0.0101, r2: 0.9998). Because 5-methylTHF concentrations and concentrations of other folate forms are rarely higher than 100 and 50 nmol/L in serum [3], we limited our daily calibration range to these lower concentrations. The variability (CV) of the daily calibration slopes over 10 days was < 10% for each folate form except for FA: 5-methylTHF 2.8%, FA 11.3%, THF 8.7%, 5-formylTHF 3.2%, 5,10-methenylTHF 5.6%, and MeFox 4.9%. The average calibrator accuracy was generally within 5% of the nominal value (except for the lowest calibrator for FA where it was within 9%) (Table 2). The average calibrator drift (reinjection at the end of the run) was < 2% from the calculated calibrator value (first injection) for each folate form. Similar calibrator accuracy data were obtained for method 2 (see Table S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material).

Table 2.

Analytical performance of method 3 (scaled down 96-probe SPE LC-MS/MS method)

| Analytea | Calibrationb |

Imprecisionc |

Accuracyd |

Sensitivitye |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level (nmol/L) |

Accuracy (%) |

CV (%) |

QC pool (nmol/L) |

Total CV (%) |

Within- run CV (%) |

Between- run CV (%) |

Spike (nmol/L) |

Spike recovery (%) |

CV (%) |

LOD (nmol/L) |

LLOQ (nmol/L) |

|

| 5-MethylTHF | 1 | 102 | 8.7 | 19.5 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2 | 97 | 35 | 0.06 | 0.19 |

| 2 | 101 | 5.7 | 35.1 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 4 | 93 | 8.8 | |||

| 4 | 102 | 3.2 | 51.1 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 20 | 105 | 7.7 | |||

| 20 | 99 | 2.3 | 100 | 103 | 5.9 | |||||||

| 100 | 100 | 1.8 | ||||||||||

| FA | 0.5 | 109 | 9.0 | 0.72 | 8.7 | 3.5 | 8.3 | 1 | 92 | 15 | 0.28 | 0.94 |

| 1 | 103 | 5.9 | 5.85 | 8.7 | 3.0 | 8.4 | 2 | 100 | 2.1 | |||

| 2 | 100 | 3.3 | 11.4 | 6.6 | 3.2 | 6.2 | 10 | 104 | 5.0 | |||

| 10 | 98 | 3.1 | 50 | 105 | 3.1 | |||||||

| 50 | 100 | 2.7 | ||||||||||

| THF | 0.5 | 101 | 25 | 1.33 | 11.1 | 7.9 | 9.6 | 1 | 93 | 7.7 | 0.20 | 0.65 |

| 1 | 100 | 14 | 4.40 | 7.4 | 3.2 | 7.0 | 2 | 99 | 7.0 | |||

| 2 | 100 | 5.4 | 10 | 103 | 4.8 | |||||||

| 10 | 100 | 5.2 | 50 | 103 | 4.5 | |||||||

| 50 | 100 | 3.6 | ||||||||||

| 5-FormylTHF | 0.5 | 105 | 11 | 0.68 | 11.4 | 4.4 | 11.0 | 1 | 84 | 11 | 0.12 | 0.41 |

| 1 | 101 | 6.6 | 2.49 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2 | 92 | 12 | |||

| 2 | 101 | 4.7 | 10 | 96 | 10 | |||||||

| 10 | 99 | 2.6 | 50 | 94 | 11 | |||||||

| 50 | 100 | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| 5,10-MethenylTHF | 0.5 | 101 | 17 | 1.56 | 8.2 | 4.8 | 7.5 | 1 | 98 | 13 | 0.31 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 101 | 6.4 | 4.77 | 5.5 | 1.4 | 5.4 | 2 | 106 | 10 | |||

| 2 | 103 | 6.1 | 10 | 113 | 12 | |||||||

| 10 | 99 | 2.9 | 50 | 113 | 12 | |||||||

| 50 | 99 | 1.8 | ||||||||||

| MeFox | 0.5 | 99 | 8.7 | 1.44 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 1 | 92 | 11 | 0.08 | 0.25 |

| 1 | 99 | 5.0 | 1.52 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 2 | 101 | 4.5 | |||

| 2 | 102 | 3.7 | 2.96 | 4.9 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 10 | 104 | 5.3 | |||

| 10 | 99 | 1.8 | 50 | 103 | 5.1 | |||||||

| 50 | 100 | 1.6 | ||||||||||

5-MethyTHF, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate; FA, folic acid; THF, tetrahydrofolate; 5-formylTHF, 5-formyltetrahydrofolate; 5,10-methenylTHF, 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate; MeFox, pyrazino-s-triazine derivative of 4α-hydroxy-5-methylTHF

Calibration was performed over 10 runs (two replicates per run) and calibrator accuracy was calculated as the mean percent difference between the measured and nominal calibrator value

Method imprecision was assessed by analyzing three QC pools (two for THF, 5-formylTHF, and 5,10-methenylTHF) over 10 runs (two replicates per run) and by calculating the total, within- and between-run coefficient of variation (CV)

Method accuracy was assessed through spike recovery; the low serum QC pool was amended with a calibrator mixture containing each folate form at four levels (two replicates per level, three runs) and also measured unspiked (two replicates per run, three runs) for endogenous folate concentrations; the spike recovery was calculated as the measured concentration difference between the spiked and unspiked sample divided by the nominal concentration of the spike

Method sensitivity was estimated as the limit of detection (LOD) for each analyte by serially diluting the medium serum QC pool with 0.1% ascorbic acid and calculating the standard deviation at a concentration of zero (σ0) from an extrapolation of repeat analyte measurements (three replicates per dilution, three runs) made near the detection limit in these dilutions; the LOD was defined as 3 σ0; the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) was defined as 10 σ0; when using 4% albumin as a diluent to simulate protein matrix, we obtained similar LOD values (nmol/L): 5-methylTHF 0.09, FA 0.24, THF 0.33, 5-formylTHF 0.18, 5,10-methenyl THF 0.53, MeFox 0.10

The measurement sensitivity, as expressed by the LOD for each analyte in serum, was overall comparable between method 3 (≤ 0.31 nmol/L, Table 2) and method 2 (≤ 0.37 nmol/L, see Table S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material; same LOD values applied to method 1). We also found similar LOD values if we used 4% albumin (instead of 0.1% ascorbic acid) as a diluent to simulate a protein matrix (Table 2 and Table S2). The LOD values were commensurate or better to other published multi-analyte folate LC-MS/MS methods [17, 19, 20]. Future enhancements in instrument sensitivity, ionization modes, or stationary phases would mostly benefit analytes such as THF, 5-formylTHF, and 5,10-methenylTHF because they occur in serum at very low concentrations, while serum concentrations of 5-methylTHF are well above the LOD and concentrations of MeFox and FA are mostly above the LOD. While some methods improved the analytical sensitivity by taking the SPE eluate to dryness and reconstituting the sample in a small volume [15, 17, 20, 21], we avoided such a step as it increases the sample preparation time and may lead to folate oxidation (21). Typical method 3 tandem multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) profiles for the low (5-methylTHF, FA and MeFox) or medium (THF, 5-formylTHF and 5,10-methenylTHF) serum QC pool are shown in Fig S1 and S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material. Most traces showed a “clean” profile; however the THF trace showed some neighboring peaks that were reasonably well resolved from the THF peak. Because we did not change the chromatography of method 1, there was no need to reassess the method selectivity or the potential for the matrix to suppress or enhance the ion signals for methods 2 and 3. We previously showed good selectivity for method 1 with virtually no contributing signals (< 0.01%) when we examined each transition for spurious signal contributions from other folate forms and a lack of matrix effects using a post-column infusion procedure [6–8].

The precision of method 3 was good with an observed total CV well below 5% for tFOL and 5-methylTHF, and well below 10% for all other folate forms (except for THF and 5-formylTHF at concentrations < 1.5 nmol/L; 11%) (Table 2). We obtained similarly good precision for method 2 (see Table S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material), with slightly higher CV for some analytes. The total CV for method 1 used over a period of one year (n = 122) was also generally comparable (tFOL < 3%, 5-methylTHF < 3%, MeFox < 7%, 5,10-methenylTHF ≤ 8%, 5-formylTHF ≤ 10%), except for a few analytes where it was higher (THF ≤ 13%, FA ≤ 17%) (data not shown). It has been suggested that generally applicable quality goals based on biologic variation should be used to assess whether the method precision is acceptable; the analytical variation CVa should be a fraction of the within-person biologic variation CVw: optimum performance, CVa = 0.25 × CVw, desirable performance, CVa = 0.5 × CVw, minimum performance, CVa = 0.75 × CVw [22]. Using data from NHANES 1999–2002, serum (total) folate was reported to have a within-person biologic variation of 21.5% [23]. Therefore, the optimum, desirable, and minimum precision performance criteria would be < 5.4%, < 10.8%, and < 16.1%, respectively. Method 3 falls into the optimum performance category for tFOL, and also for 5-methylTHF and MeFox, if we apply the same criteria to the latter folate forms; it falls into the desirable performance category for the other folate forms. Other published multi-analyte folate LC-MS/MS methods have not reported the CV for tFOL, but they also reported ≤ 5% CV for 5-methylTHF and higher CV for minor folate forms, in some cases not achieving the desirable or minimum performance categories [17, 19, 20].

The use of isotopically labeled internal standards during sample processing is expected to correct for any potential folate losses. We found nearly complete spiking recoveries (100 ± 10%) for all folate forms at almost all spiking levels for methods 2 (Table S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material) and 3 (Table 2), but method 3 (92%–108% mean spiking recovery) performed better than method 2 (87%–105% mean spiking recovery) and showed complete (100 ± 1%) recoveries for 5-methylTHF, FA, THF, and MeFox (Fig 1, panel A). These recoveries were higher than those reported by other published multi-analyte folate LC-MS/MS methods [17, 19, 20]. The reason for the improved recoveries with method 3 lie in the improved SPE efficiencies (Fig 1, panel B). SPE efficiencies were consistently better for all folate forms, particularly for the most labile folate form THF (method 3, 78%; method 2, 57%), likely due to the much faster 96-probe SPE process in method 3 compared to the 8-probe SPE in method 2. The spiking recoveries and SPE efficiencies obtained with method 2 (see Table S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material) were similar to previously reported results from method 1 [6–8].

Fig. 1.

Spiking recovery and SPE efficiency of folate forms added to serum for methods 2 (8-probe) and 3 (96-probe)

The low serum QC pool was spiked with a calibrator mixture containing each folate form at four levels (two replicates per level, three runs; 2, 4, 10, and 100 nmol/L spike for 5-methylTHF; 1, 2, 10, and 50 nmol/L spike for all other folate forms) and also measured unspiked (two replicates per run, three runs) for endogenous folate concentrations. The mixture of internal standards was added at the same time as the spike in the spike recovery experiment, but after SPE was completed in the SPE efficiency experiment. The spiking recovery and SPE efficiency were calculated as the measured concentration difference between the spiked and unspiked sample divided by the nominal concentration of the spike. Bars represent the average from the four spiking levels and error bars represent the 95% confidence limit of the mean of all data (n = 24). Spike recovery results for each individual spiking level can be found in Table 2 (method 3) and Table S2 (method 2). 5-MethyTHF, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate; FA, folic acid; THF, tetrahydrofolate; 5-formylTHF, 5-formyltetrahydro-folate; 5,10-methenylTHF, 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate; MeFox, pyrazino-s-triazine derivative of 4α-hydroxy-5-methylTHF.

Serum-based international reference materials for folate have been available for several years, unfortunately though certified concentrations are provided for 5-methylTHF only. The 5-methylTHF concentrations we obtained for the two NIST materials (SRM 1955 and 1950) and the NIBSC material were up to 12% higher than the certified concentrations (Table 3). Methods 1 and 2 generally showed similar results within less than ± 10% of the certificate value and the uncertainties for methods 1 and 2 were similar to and overlapped with the Certificate uncertainties. Method 3 showed slightly higher 5-methylTHF results, likely due to the improved recovery of 5-methylTHF, and while the uncertainties for method 3 were again similar to the Certificate uncertainties, they no longer overlapped. However, because we have taken all necessary steps to ensure accurate calibration and the recovery for method 3 is complete, we believe that the 5-methylTHF results produced by this method are accurate. FA and MeFox were the only other two folate forms detected in these reference materials, all other folate forms were < LOD. Concentrations (mean ± SD, nmol/L) obtained with method 3 (shown below) were within less than ± 10% of those obtained with the other two methods: NIST SRM 1955: Level 1, FA 0.80 ± 0.09, MeFox 1.52 ± 0.05; Level 2, FA 1.65 ± 0.14, MeFox 3.50 ± 0.13; Level 3, FA 1.70 ± 0.17, MeFox 5.61 ± 0.22; NIST SRM 1950: FA 4.45 ± 0.16, MeFox 2.03 ± 0.16; NIBSC 03-178: FA 0.66 ± 0.07, MeFox 2.24 ± 0.09.

Table 3.

Concentrationsa for 5-methyltetrahydrofolate in serum-based international reference materials obtained by different LC-MS/MS methods and difference compared to the value reported on the Certificate

| Reference material | Certificate | Method 1: Routine 8-probe SPE |

Method 2: Scaled down 8-probe SPE |

Method 3: Scaled down 96-probe SPE |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (nmol/L) |

Concentration (nmol/L) |

Difference (%) |

Concentration (nmol/L) |

Difference (%) |

Concentration (nmol/L) |

Difference (%) |

|

| NIST SRM 1955 | |||||||

| Level 1 | 4.26 ± 0.26 | 4.63 ± 0.29 | 8.2 | 4.63 ± 0.29 | 8.5 | 4.79 ± 0.27 | 12.3 |

| Level 2 | 9.73 ± 0.24 | 10.2 ± 0.30 | 5.3 | 10.1 ± 0.29 | 4.2 | 10.8 ± 0.28 | 10.5 |

| Level 3 | 37.1 ± 1.39 | 37.8 ± 1.67 | 2.4 | 39.2 ± 1.69 | 5.9 | 40.1 ± 1.55 | 8.3 |

| NIST SRM 1950 | 26.9 ± 0.78 | 26.7 ± 0.90 | −0.6 | no data | n/a | 29.2 ± 0.83 | 8.5 |

| NIBSC 03/178 | 9.75 (5.5) | 10.2 (4.2) | 5.0 | 10.2 (3.7) | 4.9 | 10.3 (3.1) | 5.4 |

Concentrations represent mean ± expanded uncertainty (nmol/L) for NIST SRM 1955 and 1950 and mean (% CV) for NIBSC 03/178; the expanded uncertainty for the three LC-MS/MS methods was calculated as follows: u = 2 × SQRT [(SD^2/n) + (U/2)^2], with SD being the standard deviation obtained from a total of n = 10 (method 1), n = 6 (method 2), and n = 12 (method 3) measurements and U being the expanded uncertainty reported in the certificate of analysis; the % CV for the three LC-MS/MS methods was calculated as follows: CV = (SD/mean) × 100, with SD being the same as described above

Although serum is generally preferred over plasma, which tends to form micro fibrinogen clots during long-term frozen storage, plasma is sometimes the only specimen type available and we therefore wanted to assess whether it can be used interchangeably with serum. As expected, we generally found excellent and highly significant correlations between serum and plasma folate concentrations (r ≥ 0.97; see Table S3 in the Electronic Supplementary Material). Concentrations of tFOL, 5-methylTHF and FA were not significantly different between serum (reference) vs. serum from a separator tube or plasma from a Na heparin or Na citrate tube. We found a proportional bias for MeFox, with Na heparin (relative Bland-Altman bias [RBAB] −35%, P = 0005) and Na citrate (RBAB −26%, P = 0.0005) plasma concentrations being lower compared to serum, likely because the plasma was obtained faster (after 2-4 h) than the serum (overnight clotting). Interestingly, we observed no difference in 5-methylTHF concentrations between serum and Na heparin or Na citrate plasma, however the expected difference may be too small to detect (≤ 1 nmol/L). We noticed large differences in 5-methylTHF (RBAB −45%, P = 0.0005), MeFox (RBAB 108%, P = 0.0005) and consequentially tFOL (RBAB −15%, P = 0.0005) between serum and EDTA plasma and also a weaker correlation for MeFox (r = 0.78). Lastly, we found slightly lower (< 10%) FA concentrations in EDTA plasma (RBAB −5.4%, P = 0.0269) and Na heparin plasma [RBAB] −7%, P = 0.0122) compared to serum.

Hannisdal et al. also studied the influence of specimen type on 5-methylTHF and MeFox (which they preliminarily called hmTHF) for matched serum and plasma (EDTA, heparin and citrate) specimens (n = 16) kept at room temperature in the dark for up to 192 h [24]. The authors did not find specimen type differences at baseline (blood processed within < 1 h and frozen immediately at −80 °C) and 5-methylTHF concentrations were essentially stable for 48 h in serum, consistent with our findings where serum was obtained after overnight clotting. However in EDTA plasma, 5-methylTHF decreased and MeFox increased at a rate of 1.92% per h and 25.7% per h, respectively during the first phase of rapid change. In serum, the reduction of 5-methylTHF was totally recovered as MeFox after 96 h, while in EDTA plasma a smaller percentage of 5-methylTHF was recovered as MeFox. Our results were similar in that the sum of 5-methylTHF and MeFox was lower in EDTA plasma (28.4 nmol/L) than in every other specimen type (32.8–33.5 nmol/L) (Fig 2). This shows that EDTA plasma may lead to undesirable folate losses and is therefore not a good specimen type for folate analysis. In a previous in-house “anticoagulant study” in which we processed all blood specimens within 1 h of collection, we observed a smaller difference in tFOL between EDTA plasma and serum (-3.8%) [7].

Fig. 2.

Effect of specimen type and anticoagulant on folate forms

Twelve matched serum and plasma samples were analyzed with the scaled down 96-probe SPE LC-MS/MS method. K2 EDTA and Na heparin were spray dried anticoagulants, while Na citrate was a liquid (0.5 mL/5-mL vacutainer tube); folate results were multiplied by 1.1 to correct for this dilution. 5-MethyTHF, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate; FA, folic acid; MeFox, pyrazino-s-triazine derivative of 4α-hydroxy-5-methylTHF; tFOL, total folate (sum of all folate forms including MeFox); other folate forms were < LOD.

The three-way LC-MS/MS cross-over study using pristine serum specimens (n = 150) to compare methods 2 and 3 to method 1 (reference) for tFOL and the main folate forms 5-methylTHF, FA, and MeFox showed, as expected, excellent correlations (r ≥ 0.98, Table 4). Method 2 had no or only minimal bias compared to method 1: there was no difference in tFOL or MeFox concentrations; 5-methylTHF concentrations were 1.1% higher and FA concentrations were 12% higher. Method 3 showed a consistent small positive bias compared to method 1, reflected by an increased Deming slope and a proportional Bland-Altman bias (95% CI): tFOL 5.6% (4.8–6.5%), 5-methylTHF 7.3% (6.5–8.2%), FA 16% (12–19%), and MeFox 3.6% (1.7–5.5%). This is likely due to the improved recovery of folate forms with this method.

Table 4.

Comparison of folate results in serum samples obtained by different LC-MS/MS methodsa

| Folate formb | Concentration (nmol/L)c |

Pearson correlation coefficient (95% CI)d |

Deming slope (95% CI) (nmol/L)e |

Deming intercept (95% CI) (nmol/L) e |

Bland-Altman bias (95% CI) (%)f |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method 1 | 5-MethylTHF | 37.7 ± 19.8 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| FA | 1.90 ± 3.87 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| THF | 0.91 (0.38–1.14) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| 5-FormylTHF | < LOD | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| 5,10-MethenylTHF | < LOD | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| MeFox | 2.31 ± 1.56 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| tFOL | 43.3 ± 21.9 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Method 2 | 5-MethylTHF | 38.0 ± 19.7 | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.02) | 0.46 (0.03 to 0.90) | 1.13 (0.00 to 2.26) |

| FA | 2.00 ± 3.64 | 0.99 (0.99 to 1.00) | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.16) | 0.04 (-0.04 to 0.12) | 12.2 (8.66 to 15.7) | |

| THF | 0.56 (0.44–0.70) | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | |

| 5-FormylTHF | < LOD | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | |

| 5,10-MethenylTHF | < LOD | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | |

| MeFox | 2.34 ± 1.66 | 0.98 (0.98 to 0.99) | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.08) | −0.04 (−0.13 to 0.05) | −0.13 (−2.21 to 1.94) | |

| tFOL | 43.5 ± 21.8 | 0.99 (0.99 to 0.99) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 0.05 (−0.54 to 0.63) | 0.42 (−0.58 to 1.42) | |

| Method 3 | 5-MethylTHF | 40.6 ± 21.4 | 0.99 (0.99 to 1.00) | 1.07 (1.06 to 1.09) | 0.12 (−0.24 to 0.47) | 7.33 (6.46 to 8.20) |

| FA | 2.09 ± 3.92 | 0.99 (0.99 to 1.00) | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.15) | 0.07 (0.00 to 0.14) | 15.6 (12.4 to 18.8) | |

| THF | 0.33 (0.14–0.62) | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | |

| 5-FormylTHF | 0.22 (0.09–0.26) | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | |

| 5,10-MethenylTHF | < LOD | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | |

| MeFox | 2.46 ± 1.76 | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.15) | −0.12 (−0.18 to −0.06) | 3.64 (1.74 to 5.54) | |

| tFOL | 46.0 ± 23.7 | 0.99 (0.99 to 1.00) | 1.08 (1.06 to 1.10) | −0.69 (−1.22 to −0.16) | 5.63 (4.78 to 6.47) |

Method comparison consisted of 150 pristine serum samples analyzed simultaneously by all three methods; method 1: routine 8-probe SPE; method 2: scaled down 8-probe SPE; method 3: scaled down 96-probe SPE

5-MethyTHF, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate; FA, folic acid; THF, tetrahydrofolate; 5-formylTHF, 5-formyltetrahydrofolate; 5,10-methenylTHF, 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate; MeFox, pyrazino-s-triazine derivative of 4α-hydroxy-5-methylTHF; tFOL, total folate (sum of all folate forms including MeFox)

Estimate represents mean ± SD for 5-methylTHF, FA, MeFox, and tFOL and median (interquartile range) for THF, 5-formylTHF, and 5,10-methenylTHF; LOD (nmol/L) for 5-formylTHF: 0.30 (methods 1 and 2), 0.12 (method 3); LOD (nmol/L) for 5,10-methenylTHF: 0.34 (methods 1 and 2), 0.31 (method 3)

Correlation, regression and bias were assessed relative to the routine 8-probe SPE LC-MS/MS method

Weighted Deming regression was used because the SD increased over the range of folate concentrations; the routine 8-probe SPE LC-MS/MS method was used as the reference

Relative Bland-Altman bias (%) was used to assess the magnitude of the difference between two methods because of increasing SD over the range of folate concentrations

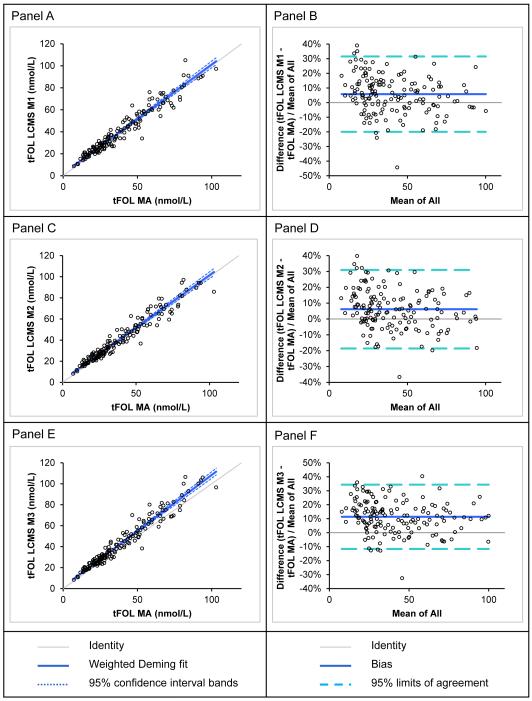

In a second three-way cross-over study, we compared the tFOLMA (reference) for the same serum specimens analyzed from a separate pristine aliquot to the LC-MS/MS calculated tFOLwithout MeFox because the MA does not respond to MeFox, a biologically inactive folate form (Fig 3). The MA mean tFOLMA (± SD) was 39.3 ± 21.3 nmol/L, while the three LC-MS/MS means tFOLwithout MeFox were: method 1, 41.0 ± 21.3 nmol/L; method 2, 41.1 ± 21.2 nmol/L; and method 3, 43.6 ± 23.0 nmol/L. We found good correlations: method 1 vs. MA, r = 0.97; method 2 vs. MA, r = 0.97; and method 3 vs. MA, r = 0.97 (see Table S4 in the Electronic Supplementary Material). For each comparison, the LC-MS/MS tFOLwithout MeFox was significantly higher than the tFOLMA, reflected by a proportional Bland-Altman bias (95% CI): method 1 vs. MA, 5.8% (3.6–7.9%); method 2 vs. MA, 6.2% (4.2–8.2%); and method 3 vs. MA, 11% (9.5–13%). To allow trending of future NHANES folate data in both directions, we also report the Deming regression equations for the conversion of LC-MS/MS to MA results (see Table S4 in the Electronic Supplementary Material).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of total folate results in serum samples obtained by different LC-MS/MS methods and by microbiologic assay

Method comparison consisted of two separate aliquots of 150 pristine serum samples, one aliquot analyzed by microbiologic assay (MA) for tFOLMA and the second aliquot analyzed by three different LC-MS/MS methods (method 1: routine 8-probe SPE; method 2: scaled down 8-probe SPE; method 3: scaled down 96-probe SPE) for folate forms that were summed up for tFOLwithout MeFox because the MA does not respond to the biologically inactive MeFox. Panels A, C and E show weighted Deming regressions (because the SD increased over the range of folate concentrations) with tFOL by MA as the reference. Panels B, D and F show relative Bland-Altman plots (because the distribution of differences was not normal) with the tFOL by MA as the reference; “mean of all” is the mean of the two methods.

Biochemical analyses methods used as part of population biomonitoring require several features to make them suitable for this type of application: (1) low imprecision to allow distinction of concentration distribution curves across different subgroups; (2) high accuracy to ensure that accepted cutoffs of nutrient adequacy or clinical deficiency are appropriate for the survey context; (3) long-term stability to establish trends in estimates over time; (4) good sensitivity to ensure a high analyte detection frequency in the population; (5) low specimen test volume because generally a panel of biochemical analyses have to be conducted from the collected sample; and (6) high sample throughput because typically several thousand samples have to be analyzed per year and results of clinical relevance have to be reported back to the participant in a timely manner. This report presents an improved and validated routine biomonitoring method for five folate vitamers and one oxidation product of 5-methylTHF in serum. The method displays five of the six required features, which makes it highly suitable for population biomonitoring. Its application over time to population studies will demonstrate whether it will also provide good long-term stability. Regular use of the available international reference materials helps to document method stability, however reference materials with certified concentrations for all detected folate forms as well as tFOL are urgently needed to anchor method accuracy to a traceability chain.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

No specific sources of financial support. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views or positions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

References

- 1.Yetley EA, Pfeiffer CM, Phinney KW, Fazili Z, Lacher DA, Bailey RL, Blackmore S, Bock J, Brody LC, Carmel R, et al. Biomarkers of folate status in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): a roundtable summary. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:303S–12S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.013011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Q, Cogswell ME, Hamner HC, Carriquiri A, Bailey LB, Pfeiffer CM, Berry RJ. Folic acid source, usual intake, and folate and vitamin B12 status in US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:64–72. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fazili Z, Pfeiffer CM, Zhang M. Comparison of serum folate species analyzed by LC-MS/MS with total folate measured by microbiologic assays and Bio-Rad radioassay. Clin Chem. 2007;53:781–84. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.078451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yetley EA, Coates PM, Johnson CL. Overview of a roundtable of NHANES monitoring of biomarkers of folate and vitamin B-12 status: measurement procedure issues. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:297S–302S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.017392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfeiffer CM, Zhang M, Lacher DA, Molloy AM, Tamura T, Yetley EA, Picciano M-F, Johnson CL. Comparison of serum and red blood cell folate microbiologic assays for national population surveys. J Nutr. 2011;141:1402–9. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.141515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfeiffer CM, Fazili Z, McCoy L, Zhang M, Gunter EW. Determination of folate vitamers in human serum by stable-isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry and comparison with radioassay and microbiologic assay. Clin Chem. 2004;50:423–32. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.026955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fazili Z, Pfeiffer CM. Measurement of folates in serum and conventionally prepared whole blood lysates: application of an automated 96-well plate isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry method. Clin Chem. 2004;50:2378–81. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.036541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fazili Z, Pfeiffer CM. Accounting for an isobaric interference allows correct determination of folate vitamers in serum by isotope dilution-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Nutr. 2012;143:108–13. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.166769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caudill SP, Schleicher RL, Pirkle JL. Multi-rule quality control for the age-related eye disease study. Stat Med. 2008;27:4094–106. doi: 10.1002/sim.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services [cited 08 February 2013];Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation. Food and Drug Administration. 2001 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../Guidances/ucm070107.pdf.

- 11.National Institute of Standards and Technology [cited 09 October 2012];Certificate of analysis, standard reference material 1955, homocysteine and folate in frozen human serum. 2008 doi: 10.1258/acb.2010.010094. Available from: https://www-s.nist.gov/srmors/certificates/1955.pdf?CFID=1979088&CFTOKEN=e0f2df69af7e3f9e-E52B4E5A-D3F5-ADF4-0BC8FFDC3BB1C0C6&jsessionid=f030b44ef80dbe9549eb287366473b7c6c3b. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.National Institute of Standards and Technology [cited 09 October 2012];Certificate of analysis, standard reference material 1950, metabolites in human plasma. 2011 Available from: https://www-s.nist.gov/srmors/certificates/1950.pdf?CFID=1979097&CFTOKEN=aab280e30cbdde55-E52EE52D-FAB2-791A-ED2004079DDD64AD&jsessionid=f0308a1c78b0b3633f28572b4f1ba5775552.

- 13.National Institute for Biological Standards and Control [cited 09 October 2012];WHO International Standard, Vitamin B12 and serum folate, NIBSC code: 03/178. (version 2.0). 2008 dated 04/04/2008. Available from: http://www.nibsc.ac.uk/documents/ifu/03-178.pdf.

- 14.Taylor JK. Quality assurance of chemical measurement. Lewis, Boca Raton: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kok RM, Smith DE, Dainty JR, van den Akker JT, Finglas PM, Smulders YM, Jakobs C, de Meer K. 5-Methyltetrahydrofolic acid and folic acid measured in plasma with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometery: applications to folate absorption and metabolism. Anal Biochem. 2004;326:129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson BC, Satterfield MB, Sniegoski LT, Welch MJ. Simultaneous quantification of homocysteine and folate in human serum or plasma using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2005;77:3586–93. doi: 10.1021/ac050235z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirsch SH, Knapp J-P, Herrmann W, Obeid R. Quantification of key folate forms in serum using stable-isotope dilution ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chrom B. 2010;878:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mönch S, Netzel M, Netzel G, Rychlik M. Quantitation of folates and their catabolites in blood plasma, erythrocytes and urine by stable isotope dilution assays. Anal Biochem. 2010;398:150–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Büttner BE, öhrvik VE, Witthöft CM, Rychlik M. Quantification of isotope labeled and unlabeled folates in plasma, ileostomy and food samples. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;399:429–39. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannisdal R, Ueland PM, Svardal A. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of folate and folate catabolites in human serum. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1147–54. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.114389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirsch SH, Herrmann W, Geisel J, Obeid R. Assay of whole blood (6S)-5-CH3-H4 folate using ultra performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404:895–902. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser CG, Hyltoft PP, Libeer JC, Ricos C. Proposals for setting generally applicable quality goals based on biology. Ann Clin Biochem. 1997;34:8–12. doi: 10.1177/000456329703400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacher DA, Hughes JP, Carroll MD. National health statistics reports. no 21. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2010. Biological variation of laboratory analytes based on the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hannisdal R, Ueland PM, Eussen SJ, Svardal A, Hustad S. Analytical recovery of folate degradation products formed in human serum and plasma at room temperature. J Nutr. 2009;139:1415–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.105635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.