Abstract

Purpose

Anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) is proposed as a biomarker of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). This study investigated: 1) AMH concentrations in obese adolescents with PCOS vs. without PCOS, 2) the relationship of AMH to sex steroid hormones, adiposity and insulin resistance, and 3) the optimal AMH value and the multivariable prediction model to determine PCOS in obese adolescents.

Methods

AMH levels were measured in 46 obese PCOS girls and 43 obese non-PCOS girls. Sex steroid hormones, clamp-measured insulin sensitivity and secretion, body composition and abdominal adiposity were evaluated. Logistic regression and receiver operating characteristic curve analyses were used and multivariate prediction models were developed to test the utility of AMH for the diagnosis of PCOS.

Results

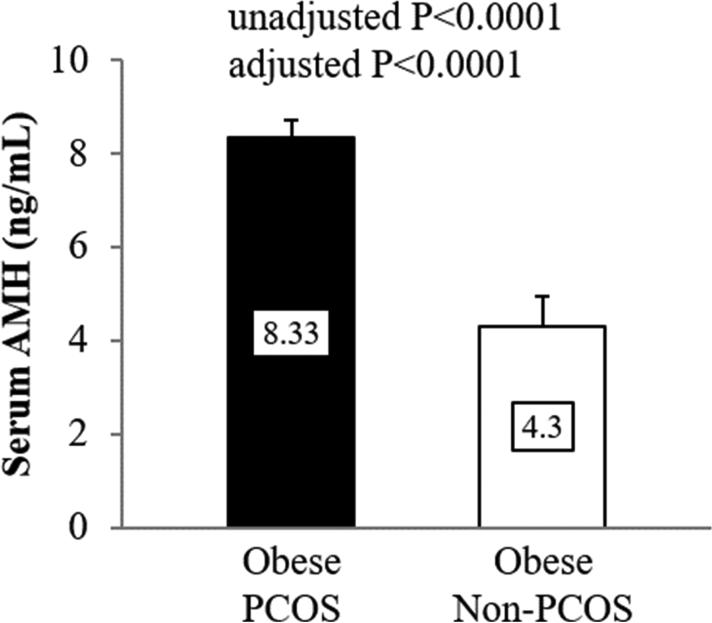

AMH levels were higher in obese PCOS vs. non-PCOS girls (8.3 ± 0.6 vs. 4.3 ± 0.4 ng/mL, P<0.0001), of comparable age and puberty. AMH concentrations correlated positively with age in both groups, total and free testosterone in PCOS girls only, abdominal adipose tissue in non-PCOS girls, with no correlation to in vivo insulin sensitivity and secretion in either group. A multivariate model including AMH (cutoff 6.26 ng/mL, area under the curve 0.788) together with sex-hormone binding globulin and total testosterone exhibited 93.4% predictive power for diagnosing PCOS.

Conclusions

AMH may be a useful biomarker for the diagnosis of PCOS in obese adolescent girls.

Keywords: AMH, PCOS, Hyperandrogenemia, Obese adolescents

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder affecting females of reproductive age. PCOS is characterized by menstrual dysfunction, clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism, with or without polycystic ovaries (PCO), and insulin resistance (1). Given the heterogeneous nature of this condition, various combinations of clinical, biological and ultrasonographic criteria have been proposed for the diagnosis of PCOS in adult women (2, 3) and adolescent girls (1, 4).

Obesity is a rapidly growing threat with significant associations between excess body fat and reproductive endocrinology and menstrual cycles in adult women and adolescent girls (5). In adolescents, as puberty progresses menstrual dysfunction appears in up to 40% of severely obese adolescents (6). Moreover, some data show that androgen levels are elevated in obese girls compared with normal weight girls across puberty (7). Against this backdrop of increasing rates of obesity, difficulties arise in distinguishing obesity-related dysfunction from PCOS-related abnormalities. In 2004, PCO evaluated by ultrasonography, was added as a diagnostic measure to the Rotterdam PCOS criteria (3). Additionally, there has been a growing interest to test the utility of anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) as a biomarker/predictor for PCO and/or PCOS (8, 9).

Due to the significant correlation between AMH and antral follicle count (AFC) in women with and without PCOS (9-11), AMH was introduced as a surrogate measure of PCO, in addition to being a biomarker of PCOS because of its associations with other criteria of PCOS including oligomenorrhea and hyperandrogenism (12-14). A recent meta-analysis suggested a 4.7 ng/mL as an optimal AMH concentration for diagnosing PCOS, based mostly on adult studies (only one pediatric study was included), with AMH cutoff levels ranging between 2.8-8.4 ng/mL (8). Data with respect to the diagnostic utility of AMH in adolescents with PCOS particularly in obese adolescents are sparse (15-20). Therefore, the purpose of this study was: 1) to investigate AMH levels in obese adolescent girls with PCOS in comparison to obese girls without PCOS, 2) to assess the relationship of AMH to sex steroid hormone profile, adiposity measures and insulin resistance, a major metabolic component of PCOS, and 3) to examine the optimal AMH cutoff and the multivariable prediction model to predict PCOS in obese girls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Data from 46 girls with a diagnosis of PCOS (5 overweight and 41 obese, age 14.9 ± 0.2 years, body mass index [BMI] 37.7 ± 1.1 kg/m2 [mean ± SE]), recruited from the PCOS Center at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, were compared with 43 girls without PCOS (12 overweight and 31 obese, age 14.4 ± 0.2 years, BMI 33.1 ± 1.1 kg/m2) who participated in our NIH-funded K24 grant investigating insulin resistance in childhood, some of whose data, unrelated to AMH, have been published (21-23). Eligible PCOS patients and their families were informed about the study while being evaluated in the PCOS center and given the opportunity to participate shortly after their diagnosis and before pharmacologic therapy was initiated. Additionally, flyers were posted in the medical campus, pediatricians’ offices, and city bus routes for interested individuals to contact us to learn about the study and assess eligibility. Consistent with our previous publications (21-25), the diagnosis of PCOS was made based on the presence of clinical signs and symptoms of hyperandrogenism and/or biochemical hyperandrogenemia after excluding other causes of hyperandrogenemia according to the NIH and the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines (1). Specifically, PCO morphology was not included in the PCOS criteria used for adolescents (26), which is different from other criteria such as the Androgen Excess Society or the Rotterdam. Recently, the Pediatric Endocrine Society recommended that no compelling criteria to define PCO morphology have been established for adolescents (4). Inclusion criteria were: 1) PCOS diagnosis as above; 2) age 10-20 years and postmenarche, and 3) BMI ≥85th percentile for age and sex. Girls who were previously diagnosed with systemic or psychiatric disease and were taking any medications that impact carbohydrate or lipid metabolism (oral contraceptive pills [OCPs], metformin, anti-epileptics, anti-psychotics, statins and fish oil) were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh, and written informed parental consent and child assent were obtained from all participants before any research participation in accordance with the ethical guidelines of Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh.

Procedures

All procedures were performed at the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center (PCTRC) of Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh. All participants underwent medical history, physical examination, and hematologic and biochemical tests. Height and weight were assessed to the nearest 0.1cm and 0.1kg, respectively, and used to calculate BMI. Pubertal development was assessed using Tanner criteria (27). Fasting blood samples were collected for determination of sex hormone profile including total and free testosterone, sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG), estradiol and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS).

Body composition was evaluated with DEXA with measurement of total body fat mass and percent body fat. Abdominal total adipose tissue (TAT), subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) were assessed by either computed tomography (CT) at L4-5 intervertebral space or MRI (28, 29). The switch from CT to MRI was imposed by the study section during the competitive grant renewal. However, there is a strong correlation (r=0.89-0.95) and good agreement between CT and MRI for the measurement of abdominal adipose tissue (30).

Metabolic Studies

All participants underwent a 2-hr oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) to assess glucose tolerance status (22, 25). Obese girls with PCOS and without PCOS were admitted twice within a 1-4 week period to the PCTRC for a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, to assess in vivo insulin sensitivity, and a hyperglycemic clamp, to assess insulin secretion, performed in random order (22, 24, 25). Each clamp evaluation was performed after a 10- to 12-hr overnight fast.

Fasting hepatic glucose production was measured before the start of the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, with a primed (2.2 μmol/kg) constant infusion of [6,6-2H2] glucose at 0.22 μmol/kg/min for a total of 2 hours as described (22, 24). After the 2-hr baseline isotope infusion period, in vivo insulin sensitivity was evaluated during a 3-hr hyperinsulinemic (80 mU/m2/min)-euglycemic clamp (22, 24, 25). First- and second-phase insulin secretion was assessed during a 2-hr hyperglycemic (225 mg/dL) clamp as described before (22, 24, 25). Plasma glucose was increased rapidly to 225 mg/dL by a bolus infusion of dextrose and maintained at that level by a variable rate infusion of 20% dextrose for 2 hours, with frequent measurement of glucose and insulin concentrations.

Biochemical Measurements

Total testosterone was measured by high-pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectroscopy and DHEAS by RIA in dilute serum after hydrolysis (Esoterix Inc., Calabasas Hills, CA). Free testosterone was measured by equilibrium dialysis and SHBG by immunoradiometric assay. Serum AMH was measured in duplicate by using the Ansh Labs Ultra-Sensitive AMH ELISA (Webster, TX, USA). The intra- and inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) were 8.5% and 5.8%, respectively. Plasma glucose was measured with a glucose analyzer (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH) and insulin was measured by RIA (22).

Calculations

Fasting hepatic glucose production was calculated during the last 30 min of the 2-hr isotope infusion (−30 to 0 min) according to steady-state tracer dilution equations (22, 25). Hepatic insulin sensitivity was calculated as the inverse of the product of hepatic glucose production and fasting plasma insulin concentration (22, 31). Insulin-stimulated glucose disposal (Rd) was calculated to be equal to the rate of exogenous glucose infusion during the final 30 min of the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp. Peripheral insulin sensitivity was calculated by dividing the Rd by the steady-state clamp insulin concentration multiplied by 100 (25). During the hyperglycemic clamp, first- and second-phase insulin concentrations were calculated as before (22, 25), first phase during the first 10 minutes and second phase from 15-120 minutes. β-cell function relative to insulin sensitivity, i.e., disposition index, was calculated as the product of insulin sensitivity and first-phase insulin secretion (22, 25).

Statistical Analyses

Independent sample t-tests and chi-square were used to compare descriptive characteristics between obese PCOS vs. non-PCOS. Analysis of covariance was used to compare phenotypes after adjusting for race, glycemic status, BMI and fat mass. Data that did not meet the assumptions for normality were log10 transformed; untransformed data are presented for ease of interpretation. Pearson correlation analyses were used to examine bivariate relationships between AMH concentrations and other variables of interest. Logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate odds ratio of AMH for the diagnosis of PCOS, with adjustment for age and BMI. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to estimate an optimal cutoff value of AMH for diagnosing PCOS based on the area under the curve for the predictive power. In addition, multivariable prediction models combining AMH with PCOS-associated variables were developed to examine the highest predictive power using the algorithm developed by DeLong et al (32). Data were presented as mean ± SEM with statistical significance set at P ≤0.05.

RESULTS

Obese Girls with PCOS vs. without PCOS

Obese PCOS girls had similar age and Tanner stage distribution, but there were more Caucasians and more girls with prediabetes, higher BMI, total fat mass and percent body fat and higher abdominal adipose tissue (VAT, SAT and TAT) compared with obese girls without PCOS (Table 1). Before and after adjusting for race, glycemic status, BMI and fat mass, girls with PCOS had lower SHBG, higher DHEAS and higher total and free testosterone compared with girls without PCOS (Table 1). Serum AMH concentration was significantly higher in obese girls with PCOS vs. girls without PCOS before and after adjusting for the covariates (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Physical characteristics and sex steroid hormones in obese girls with PCOS vs. without PCOS.

| Variables | Obese PCOS (n=46) | Obese Non-PCOS (n=43) | P | Adjusted* P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14.9 ± 0.2 | 14.4 ± 0.2 | NS | - |

| Tanner stage (III/IV/V) | 0 (0%) / 2 (4%) / 44 (96%) | 1 (2%) / 3 (7%) / 39 (91%) | NS | - |

| Race (AA/AW/Bi) | 9 (20%) / 32 (70%) / 5 (10%) | 24 (57%) / 17 (41%) / 1 (2%) | 0.001 | - |

| Glycemic status (NGT/prediabetes) | 28 (61%) / 18 (39%) | 37 (86%) / 6 (14%) | 0.007 | - |

| Anthropometrics | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 37.7 ± 1.1 | 33.1 ± 1.1 | 0.003 | - |

| Fat mass (kg) | 47.7 ± 2.2 | 38.6 ± 2.2 | 0.002 | - |

| Percent body fat (%) | 46.9 ± 0.8 | 43.1 ± 1.0 | 0.002 | - |

| VAT (cm2) | 81.2 ± 4.8 | 38.7 ± 3.7 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| SAT (cm2) | 608.3 ± 32.4 | 400.5 ± 32.7 | <0.0001 | 0.001 |

| TAT (cm2) | 683.6 ± 35.6 | 440.2 ± 35.6 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Sex steroid hormones | ||||

| Total testosterone (ng/dL) | 46.2 ± 3.1 | 24.2 ± 1.9 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 23.9 ± 2.3 | 43.8 ± 3.4 | <0.0001 | 0.003 |

| Free testosterone (pg/mL) | 10.5 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 72.0 ± 9.6 | 110.8 ± 18.6 | 0.070 | NS |

| DHEAS (ug/dL) | 159.8 ± 14.6 | 110.6 ± 8.8 | 0.015 | 0.054 |

Values are mean ± SEM, or n (%) unless otherwise indicated. One obese non-PCOS girl had not available record on race.

P adjusted for race, glycemic status, BMI and fat mass.

NS, not-significant; AA, African-American; AW, American-White; Bi, biracial; NGT, normal glucose tolerance; BMI, body mass index; VAT, visceral adipose tissue; SAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue; TAT, total adipose tissue; SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; DHEAS, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate.

Figure 1.

Serum AMH concentrations in obese adolescent girls with PCOS vs. without PCOS. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. Adjusted P is for race, glycemic status, BMI and fat mass.

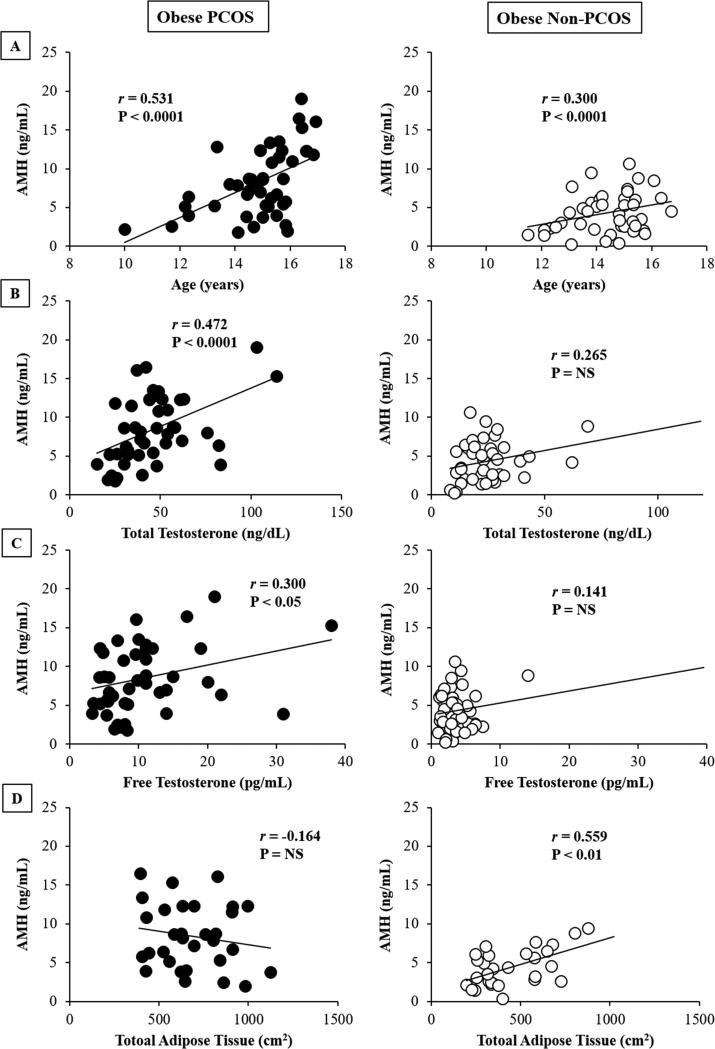

Correlation of AMH with Age, Testosterone, Abdominal Adiposity and Insulin Sensitivity

AMH concentrations correlated positively with age in both groups (Figure 2, Panel A), total and free testosterone in PCOS girls only (Figure 2, Panel B & C), and abdominal adiposity in non-PCOS girls only (Figure 2, Panel D). There were no significant correlations between AMH concentrations and fat mass, percent body fat, SHBG, DHEAS, estradiol, in vivo hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity, first- and second-phase insulin secretion, and β-cell function in either group.

Figure 2.

Relationship of AMH to age (Panel A), total and free testosterone (Panels B & C), and total abdominal adipose tissue (Panel D) in obese PCOS (Left Panel) and obese non-PCOS adolescent girls (Right panel). NS, not-significant.

Logistic Regression and ROC Curve Analyses of AMH and Multivariate Models for the Prediction of PCOS

Logistic regression analysis was conducted for estimating the odds ratio of AMH level for the diagnosis of PCOS. AMH was a significant predictor of PCOS independent of age and BMI, with odds ratio of 1.470 (B=0.385, 95% CI=1.220-1.771, P<0.0001). ROC curve analysis was performed to assess the predictive power of AMH concentrations for diagnosing PCOS and to define an optimal cutoff value with maximum sensitivity and specificity (Table 2). The optimal value of serum AMH for predicting PCOS was 6.26 ng/mL, ROC area under the curve 0.788, with 67% sensitivity and 81% specificity. A multivariate model adding to AMH, SHBG and total testosterone gave a predictive power of 0.934 for diagnosing PCOS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses of AMH, SHBG, total testosterone and multivariate models for the prediction of PCOS.

| Parameter | ROC AUC | 95 % CI | Model P value | Compared to AMH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMH | 0.788 | 0.687 - 0.868 | <0.0001 | - |

| SHBG | 0.787 | 0.692 - 0.882 | <0.0001 | 0.995 |

| Total testosterone | 0.856 | 0.776 - 0.936 | <0.0001 | 0.157 |

| Model 1 (AMH + SHBG) | 0.887 | 0.801 - 0.944 | <0.0001 | 0.018 |

| Model 2 (SHBG + Total testosterone) | 0.923 | 0.866 - 0.980 | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 (AMH + SHBG + Total testosterone) | 0.934 | 0.861 - 0.976 | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

AUC, Area Under the Curve; CI, Confidence Interval.

DISCUSSION

The present investigation reveals that in obese adolescent girls with PCOS AMH levels are almost twice as high as in obese non-PCOS girls. While AMH levels correlate positively with age in both PCOS and non-PCOS girls, it correlates with total testosterone and free testosterone only in PCOS girls, and unlike non-PCOS girls it shows no relationship to abdominal adiposity in PCOS girls. Independent of age and BMI, AMH is predictive of PCOS in obese girls with an optimal cutoff of 6.26 ng/mL per the used assay, with a predictive power of 78.8%. Combining AMH, with SHBG and total testosterone into a multivariate model gave a predictive power of 93.4% for diagnosing PCOS in obese adolescents.

AMH, produced by the granulosa cells of the primary and preantral follicles in the postnatal ovary (33), is recognized as a regulator of initial follicular recruitment from the primordial pool (33-35). Dewailly et al. suggested that serum AMH is more sensitive and specific than AFC in diagnosing PCO and PCOS in adult women (9). Given that serum AMH level is relatively stable throughout and between menstrual cycles (36, 37), it seems appealing to utilize AMH as a biomarker of PCOS. However, since serum AMH levels increase during infancy and stay higher until adolescence and early adult life (38), but decline gradually afterwards until menopause (39), it is important to examine the clinical utility of AMH by distinct age groups (adolescent girls vs. adults with PCOS). Moreover, due to the difficulties of performing vaginal ultrasound in obese adolescent girls and due to the difficulties of distinguishing PCOS-related hyperandrogenic signs/symptoms from obesity-related alterations, measurement of AMH might prove beneficial as a biomarker of PCOS in obese adolescent girls.

Our cross-sectional observation of a significant difference in serum AMH concentrations between obese girls with PCOS vs. without PCOS supports and advances previous findings in the pediatric literature (15-20). However, most of the pediatric literature on AMH is in lean girls or combined non-obese and obese PCOS girls (16-20), without particular focus in obese girls. Our data show that obese girls with PCOS have ~50% higher serum AMH levels compared with obese girls without PCOS. Although the magnitude of difference in AMH concentrations between control and PCOS groups varies among various pediatric studies (ranging from 24-54%) (15-20), it should be noted that different selection criteria of the study populations/groups used (i.e., a wide range of age, BMI, and different combination of PCOS criterion or characteristics of the control group), and a variety of methods for measuring AMH may contribute to this variance.

In the present study AMH shows a significant direct relationship with total and free testosterone concentrations consistent with studies in adult women with PCOS (10). This was not the case however in obese girls without PCOS. Since androgen excess may play a critical role in the elevation of serum AMH, through impairing follicular growth and increasing the number of small antral follicles (10, 34), it is not surprising that AMH did not show any relationship to testosterone in girls without PCOS who do not have hyperandrogenemia. It is also important to note that a positive correlation between age and AMH was noted in both obese girls with and without PCOS. This direct relationship between age and AMH in adolescent girls is opposite to that in adult women with and without PCOS (12-14), but in agreement with the known age-specific changes in AMH levels from conception to menopause (39), irrespective of the presence or absence of PCOS. On the other hand, the positive relationship between abdominal adiposity and AMH observed in obese girls without PCOS was not present in PCOS girls possibly overridden by the hyperandrogenemia and its strong association with AMH concentrations.

Insulin resistance is an inherent component of PCOS, whether in adult women or adolescent girls, and compensatory hyperinsulinemia is proposed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of androgen excess in PCOS (40). Considering the scarcity of data regarding a possible relationship between insulin resistance and AMH, we aimed to evaluate if an inverse relationship exists between AMH and in vivo insulin sensitivity and secretion. However, neither in obese PCOS girls nor in control girls, there seems to be any relationship between AMH concentrations and clamp-measured insulin sensitivity and secretion. This is in further support that the driver of high AMH concentrations in PCOS is the ovarian granulosa cells.

In the current cohort an AMH concentration of 6.26 ng/mL, based on the assay used, provides an optimal cutoff to diagnose PCOS with the best combination of sensitivity (67%) and specificity (81%), and a predictive power of 78.8%. To date, the pediatric studies that have assessed the optimal AMH for predicting PCOS have not necessarily focused on obese girls. One pediatric study suggested an AMH cutoff of 4.2 ng/mL (17) while another reported a value of 3.4 ng/mL (18). However, the predictive power, the sensitivity and the specificity in the former were low (64%, 53% and 70% respectively), while the latter had a relatively small sample size (n=31). Of note 8 of 43 non-PCOS girls (18.6%) had AMH levels above 6.26 ng/mL, and 16 of 46 PCOS girls (34.8%) had AMH levels below 6.26 ng/mL. However, it has to be stressed that a statistically-derived optimal cutoff value based on the best ROC curve analysis as stated above, does not imply that this is an absolute number that applies to all patients or non-patients. This is the case with any ROC analysis. In addition to the ROC curve analysis of AMH in diagnosing PCOS, our logistic analysis suggests that AMH is a significant predictor of PCOS independent of age and BMI. For a one unit increase in AMH level the odds of having PCOS increases 47%. Moreover, the combination of AMH together with SHBG and total testosterone, all of which can be determined in a single blood sample, significantly improves the predictive power to 93.4% in diagnosing PCOS. Considering the wide spectrum of PCOS characteristics, efforts with large cohorts, lean separate from obese, while assessing AFC, should be performed to provide a reliable and reproducible AMH cutoff value for the diagnosis of PCOS in adolescent girls.

The strengths of the present investigation include: 1) an evaluation of AMH concentrations with a specific focus on obese girls with and without PCOS, 2) a comprehensive assessment from sex steroid hormones to rigorous measures of adiposity to state-of-the-art clamp-measured metabolic parameters to unravel the relationships of AMH to PCOS phenotypes, 3) an AMH cutoff value, specific for obese girls with and without PCOS, and 4) the multivariable model including AMH, SHBG and total testosterone, which provides an excellent predictive power for PCOS. Potential perceived limitations would be that we did not collect AFC data. In addition, our suggested AMH cutoff value may not apply to the all PCOS adolescents since we did not include lean girls, and also this value may be specific to the assay we used. Large pediatric cohorts should be investigated to examine the validity of AMH in diagnosing PCOS in an obese adolescent population as well as lean adolescent girls. Further, considering the narrow age range of our participants (12-16 years old), a study to examine the optimal AMH cutoff values along a wide age range, possibly 8 to less than 20 years old, and across Tanner stages I through V, and across BMI ranges from normal to overweight to obese would be highly informative.

In summary, AMH may be a useful biomarker for the diagnosis of PCOS in obese adolescent girls. AMH concentrations are ~twice higher in obese PCOS girls and correlate with hyperandrogenemia, but not adiposity, insulin resistance and β-cell function. An AMH of 6.26 ng/mL seems to be an optimal cutoff value in obese girls for predicting PCOS. Addition of SHBG and total testosterone to AMH increases the predictive power to 93.4% for diagnosing PCOS.

Implications and Contribution Summary Statement.

AMH concentrations in obese adolescent girls with PCOS are almost twice as high as non-PCOS peers and correlate positively with age and testosterone. The AMH cutoff for diagnosing PCOS is 6.26 ng/mL in these obese girls and the odds of having PCOS increases 47% for one unit increase in AMH.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the research participants and their parents, without whom science would not advance; Nancy Guerra, C.R.N.P., for her assistance; Resa Stauffer for her laboratory expertise; and the nursing staff of the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center for their outstanding care of the participants and meticulous attention to the research.

Funding Sources

This study was supported by K24-HD01357 and R01-HD27503 to SA, Richard L. Day Endowed Chair to SA, and PCTRC UL1TR000005 to Clinical and Translational Science Award.

List of abbreviations

- PCOS

Polycystic ovary syndrome

- PCO

polycystic ovaries

- AMH

anti-müllerian hormone

- AFC

antral follicle count

- BMI

body mass index

- OCPs

oral contraceptive pills

- PCTRC

Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center

- SHBG

sex-hormone binding globulin

- DHEAS

dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

- TAT

total adipose tissue

- SAT

visceral adipose tissue

- VAT

subcutaneous adipose tissue

- CT

computed tomography

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Prior Presentation

Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the 98th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society, Boston, MA, April 1-4, 2016.

Contributor Information

Joon Young Kim, Division of Weight Management and Wellness, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

Hala Tfayli, Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, American University of Beirut Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon.

Sara F. Michaliszyn, Human Performance and Exercise Science, Youngstown State University, Youngstown, Ohio, USA.

SoJung Lee, Division of Weight Management and Wellness, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

Alexis Nasr, Division of Weight Management and Wellness, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

Silva Arslanian, Division of Weight Management and Wellness, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. Division of Pediatric Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes Mellitus, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

References

- 1.Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehrmann DA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4565–92. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dumesic DA, Oberfield SE, Stener-Victorin E, et al. Scientific Statement on the Diagnostic Criteria, Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Molecular Genetics of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2015;36:487–525. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witchel SF, Oberfield S, Rosenfield RL, et al. The Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome during Adolescence. Horm Res Paediatr. 2015 doi: 10.1159/000375530. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasquali R, Pelusi C, Genghini S, et al. Obesity and reproductive disorders in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:359–72. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bandealy A, Stahl C. Obesity, reproductive health, and bariatric surgery in adolescents and young adults. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25:277–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCartney CR, Blank SK, Prendergast KA, et al. Obesity and sex steroid changes across puberty: evidence for marked hyperandrogenemia in pre- and early pubertal obese girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:430–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iliodromiti S, Kelsey TW, Anderson RA, et al. Can anti-Mullerian hormone predict the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome? A systematic review and meta-analysis of extracted data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3332–40. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewailly D, Gronier H, Poncelet E, et al. Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): revisiting the threshold values of follicle count on ultrasound and of the serum AMH level for the definition of polycystic ovaries. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:3123–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pigny P, Merlen E, Robert Y, et al. Elevated serum level of anti-mullerian hormone in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: relationship to the ovarian follicle excess and to the follicular arrest. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5957–62. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pigny P, Jonard S, Robert Y, et al. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone as a surrogate for antral follicle count for definition of the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:941–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laven JS, Mulders AG, Visser JA, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone serum concentrations in normoovulatory and anovulatory women of reproductive age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:318–23. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piouka A, Farmakiotis D, Katsikis I, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone levels reflect severity of PCOS but are negatively influenced by obesity: relationship with increased luteinizing hormone levels. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E238–43. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90684.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassar S, Teede HJ, Moran LJ, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and anti-Mullerian hormone: role of insulin resistance, androgens, obesity and gonadotrophins. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;81:899–906. doi: 10.1111/cen.12557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siow Y, Kives S, Hertweck P, et al. Serum Mullerian-inhibiting substance levels in adolescent girls with normal menstrual cycles or with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:938–44. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park AS, Lawson MA, Chuan SS, et al. Serum anti-mullerian hormone concentrations are elevated in oligomenorrheic girls without evidence of hyperandrogenism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1786–92. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart R, Doherty DA, Norman RJ, et al. Serum antimullerian hormone (AMH) levels are elevated in adolescent girls with polycystic ovaries and the polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1118–21. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sopher AB, Grigoriev G, Laura D, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone may be a useful adjunct in the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome in nonobese adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;27:1175–9. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2014-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinola P, Morin-Papunen LC, Bloigu A, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone: correlation with testosterone and oligo- or amenorrhoea in female adolescence in a population-based cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:2317–25. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savas-Erdeve S, Keskin M, Sagsak E, et al. Do the Anti-Mullerian Hormone Levels of Adolescents with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Those Who Are at Risk for Developing Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, and Those Who Exhibit Isolated Oligomenorrhea Differ from Those of Adolescents with Normal Menstrual Cycles. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016 doi: 10.1159/000446111. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arslanian SA, Lewy V, Danadian K, et al. Metformin therapy in obese adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome and impaired glucose tolerance: amelioration of exaggerated adrenal response to adrenocorticotropin with reduction of insulinemia/insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1555–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tfayli H, Ulnach JW, Lee S, et al. Drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol versus rosiglitazone treatment in overweight adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome: comparison of metabolic, hormonal, and cardiovascular risk factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1311–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughan KS, Tfayli H, Warren-Ulanch JG, et al. Early Biomarkers of Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Obese Adolescent Girls with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Pediatr. 2016;168:104–11. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewy VD, Danadian K, Witchel SF, et al. Early metabolic abnormalities in adolescent girls with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Pediatr. 2001;138:38–44. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.109603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arslanian SA, Lewy VD, Danadian K. Glucose intolerance in obese adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome: roles of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction and risk of cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:66–71. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hecht Baldauff N, Arslanian S. Optimal management of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescence. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:1076–83. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanner JM. Growth and maturation during adolescence. Nutr Rev. 1981;39:43–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1981.tb06734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Kuk JL, Hannon TS, et al. Race and gender differences in the relationships between anthropometrics and abdominal fat in youth. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1066–71. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S, Kuk JL, Kim Y, et al. Measurement site of visceral adipose tissue and prediction of metabolic syndrome in youth. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12:250–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2010.00705.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klopfenstein BJ, Kim MS, Krisky CM, et al. Comparison of 3 T MRI and CT for the measurement of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue in humans. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e826–30. doi: 10.1259/bjr/57987644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyazaki Y, Glass L, Triplitt C, et al. Abdominal fat distribution and peripheral and hepatic insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E1135–43. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.0327.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weenen C, Laven JS, Von Bergh AR, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone expression pattern in the human ovary: potential implications for initial and cyclic follicle recruitment. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:77–83. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durlinger AL, Gruijters MJ, Kramer P, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone inhibits initiation of primordial follicle growth in the mouse ovary. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1076–84. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.3.8691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durlinger AL, Gruijters MJ, Kramer P, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone attenuates the effects of FSH on follicle development in the mouse ovary. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4891–9. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hehenkamp WJ, Looman CW, Themmen AP, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone levels in the spontaneous menstrual cycle do not show substantial fluctuation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4057–63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.La Marca A, Stabile G, Artenisio AC, et al. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone throughout the human menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:3103–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lie Fong S, Visser JA, Welt CK, et al. Serum anti-mullerian hormone levels in healthy females: a nomogram ranging from infancy to adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4650–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelsey TW, Wright P, Nelson SM, et al. A validated model of serum anti-mullerian hormone from conception to menopause. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ehrmann DA. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1223–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]