Abstract

Objective

Breast cancer survivors (BCSs) experience symptoms affecting overall quality of life (QOL), often for a prolonged period post-treatment. Meditative Movement (MM), including Qigong and Tai Chi Easy (QG/TCE), has demonstrated benefit for improving QOL issues such as fatigue and sleep, but there is limited evidence of its impact on cognitive function, overall physical activity, and body weight for BCSs.

Design

This double-blind, randomized controlled pilot study with 87 female BCSs explored effects of QG/TCE on mental and physical QOL (Medical Outcomes Survey, Short Form), cognitive function (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function and two cognitive performance tests from the WAIS III), overall levels of physical activity (PA)(Brief Physical Activity Questionnaire) and body mass index (BMI).

Interventions

Twelve weekly sessions of QG/TCE were compared to sham Qigong (SQG), a gentle movement control intervention similar to QG/TCE but without the focus on breathing and meditative state.

Results

Both groups demonstrated pre-to-post-intervention improvements in physical and mental health, level of PA, self-reported cognitive function, and cognitive performance tests, though without significant differences between QG/TCE and SQG. For a subset of women enrolled later in the study, a significant reduction in BMI [−0.66 (p=0.048)] was found for QG/TCE compared to SQG.

Conclusions

Practices that include gentle movement (such as QG/TCE or our sham protocol) among women with a history of breast cancer may improve many facets of the cancer experience, including QOL, cognitive function, and PA patterns. Practicing QG/TCE may show some advantage for BMI reduction compared to non-meditative gentle exercise.

Keywords: Integrative Oncology, Breast Cancer, Cancer Survivorship, Meditative Movement, Qi Gong, Body Mass Index

1. Introduction

There were an estimated 14.5 million cancer survivors in 2014, representing approximately 4% of the population, with breast as the most common cancer site (41%) among female survivors.1 With the growing number of survivors, quality of life among breast cancer survivors (BCSs) deserves more attention in clinical practice. BCSs commonly experience symptoms well past the initial treatment phase that affect quality of life (QOL), including fatigue, depression, anxiety, cognitive dysfunction, pain, and weight gain.2–5 The suggested etiology of these symptoms has been the complex of stress responses post cancer diagnosis and treatment6 including sleep disorders, anemia, and inflammation.6,7 A number of these factors and symptoms8,9 often co-occur, possibly due to the underlying inflammatory biomarker changes most associated with fatigue, depression and sleep disorders.10,11 The search continues for interventions to alleviate these persistent symptoms.

In addition, between 50–96% of women with breast cancer reportedly experience weight gain during treatment.5 Moreover, for many BCSs, the weight gain continues for many years, even among those whose weight remained stable during treatment.5 Among those who gain weight, average increases range from 2.5–6.2 kg.12–14 This weight gain has been attributed to a pattern of stress, neuro-hormonal changes and inflammation, but fatigue, sedentary lifestyle, reduced body awareness and emotional eating likely also contribute.11 Targeting weight gain in BCSs is critical because cancer-related weight gain, as well as an overweight or obese status at diagnosis, and sedentary behavior increase the risk of recurrence and all-cause mortality for BCSs.15,16 Physical activity (PA) and weight loss for overweight and obese BCSs are important goals of behavioral interventions for the longitudinal care of BCSs.

1.1 Meditative Movement and BCSs

Among breast cancer patients and survivors, there is a growing interest and use of mind-body practices, including Meditative Movement (MM) forms of exercise, and BCSs are among the most likely to explore these complementary and alternative options.17,18 MM is defined as those practices that utilize movement or posture, with a focus on the breath and a meditative state to achieve deep states of relaxation19 and includes (but not limited to) Tai Chi (TC), Qigong (QG), and Yoga. Many of these practices may be easier for severely fatigued or health-compromised individuals to adopt compared to strenuous aerobic or resistance training. The level of exertion of these MM types of exercise varies widely, but most practices are low-impact, with low to moderate aerobic exertion [e.g., Restorative Yoga, Tai Chi Easy (TCE)].19 There is a growing body of evidence that some forms of MM provide a degree of relief for a number of persistent symptoms and QOL issues for cancer patients/survivors and BCSs, including fatigue, emotional distress, metabolic imbalances, inflammation, and sleep dysfunction.20–36

1.2 Exploratory Aims

In a recently completed study, QG/TCE was compared to a sham Qigong (SQG) control intervention for effects on fatigue, sleep quality and depression (as primary outcomes) in BCSs. The study interventions included two gentle forms of exercise, with the QG/TCE intervention incorporating the key components of MM (i.e., movement, meditative connection and breath focus) and the SQG intervention mimicking QG movements, but without the meditation and breath focus. The primary outcome results of this study are published elsewhere, showing that fatigue was significantly reduced by QG/TCE compared to SQG, and sleep and depression were improved in response to both interventions (with some advantage shown for QG/TCE).37

Additional measures in this study were proposed as exploratory variables, including mental and physical aspects of quality of life, cognitive function and performance, change in overall PA and weight change (assessed as Body Mass Index [BMI]). The hypotheses and results of these exploratory variables are reported in this current paper. Each of the variables to explore are based on prior work that mostly shows promise for these factors to be improved in response to forms of MM, but with more evidence still needed to understand specifically the effects for BCSs.

QOL

There are numerous studies indicating Yoga has significant effects on QOL for breast cancer patients and survivors.38–41 A review by Zeng and colleagues20 notes strong evidence for TC and QG to improve QOL for cancer patients in general, but studies utilizing TC and/or QG specifically for breast cancer survivors are less convincing (e.g, one study with 10 participants with non-significant results for QOL30).

Cognitive function

A recent set of studies with cancer patients undergoing treatment indicate that Medical Qigong reduces the perceptions of perceived cognitive dysfunction (possibly due to the physical activity component, or the associated mindfulness practice).42,43 Similarly, Yoga has been shown to result in reductions in cognitive complaints noted by breast cancer survivors, and TC has shown promise for improvements in a battery of memory and cognitive function tests prior to and post-intervention in a small pilot study of female cancer survivors44. More controlled trials of objective cognitive performance measures of change in response to MM are needed.

BMI

There is a growing, but mixed, body of evidence that MM may support weight loss or improvements in body composition/measurements for individuals with metabolic and cardiac conditions45–47 and for those with cancer32, making BMI an important target for exploration.39

Physical Activity (PA)

Thus far, no interventions in BCSs have evaluated how initiating an MM practice may impact overall levels of PA beyond the time of intervention practice or reduce sedentariness. With the potential for helping fatigued women get started with less vigorous activities and helping them to “get moving” again, it is of interest to examine not only the activity associated with the MM interventions, but to examine changes in overall PA, if any.

Given these trends for MM, but with limited RCTs to test breast cancer survivors’ response to TC or QG, we suggested the following exploratory hypothesis and research questions:

Exploratory Hypothesis: Breast cancer survivors completing a 12-week QG/TCE intervention will improve in QOL (including mental and physical components), cognitive function/performance and overall level of PA more than those in the SQG group.

Research Question: Will breast cancer survivors completing a 12-week QG/TCE intervention reduce weight more than those in the SQG?

2. Methods

2.1 Overview

The parent study was a parallel 2-group, double blind, randomized controlled trial (RCT) designed to test a 12-week QG/TCE class compared to a sham control intervention37 and the current report examines the impact of these interventions on a set of exploratory outcomes. Overall physical and mental health QOL, cognitive function, cognitive performance, and level of PA, were assessed at 3 time points: baseline, immediately after the 12-week intervention and again at 12 weeks post-intervention. Weight change, (using BMI metrics), was assessed at 2 time points, baseline and post-intervention for the smaller number of participants for whom these data were collected after the first two cohorts completed.

2.2 Participants and Procedures

The study was conducted in a community hospital associated with a university-based cancer center, with Institutional Review Board approval obtained through both the university and the hospital. Eligibility criteria for study inclusion required participants to be: (a) diagnosed with Stage 0-III breast cancer; (b) six months to 5 years past primary treatment (including surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy); (c) age 40 to 75; (d) post-menopausal; (e) with no evidence of recurrence or occurrence of other cancers; and (f) reporting clinically significant fatigue, scoring ≤ 50 on the 4-item Vitality scale of the Medical Outcomes Scale short form (SF-36).48 Exclusions were: a score of 15 or greater on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (indicating moderately high depression)49; a BMI > 32; and co-morbidities with a potential for confounding the study outcomes (e.g., uncontrolled diabetes; untreated hypothyroidism; chronic fatigue syndrome; auto-immune disorders); factors that could be causing fatigue other than cancer-related causes (e.g., sleep apnea, overnight shift work, low mood preceding fatigue, fatigue preceding the cancer diagnosis, or restless leg syndrome).

Patients were excluded from the study if presenting with criteria associated with risks to cancer patients’/survivors’ safety during physical activity: hematocrit < 24; severe cachexia; frequent dizziness; bone pain; or severe nausea.50 Other exclusion criteria included: regularly smoke or drink more than 2 alcoholic beverages per day; having had past or current regular experience with mind-body practices that blend movement with meditative practices, such as Yoga, Tai Chi or Qigong; use of corticosteroids, cyclosporin, or regular use of sleep-aid medications. Participants were recruited directly from community settings using direct presentations to survivor support groups, and through oncology office referrals using letters of invitation, flyers and direct provider referrals. Interested patients contacted the research office, received initial screening by phone, and then scheduled for an in-person eligibility screening. Rolling recruitment progressed over 30 months with groups of 6–18 participants starting the intervention every 4–5 months for a total of 7 cohorts. Consented individuals were randomized by the statistician at each cohort start time to the QG/TCE intervention or the SQG control condition (after study staff collected baseline data) using stratified randomization (stratified by estrogen suppressive therapy status, yes/no, and starting levels of PA, using 8.4 MET/hrs/week as high/low cut-off score) resulting in class sizes of 3–9 participants each. Participants were blinded to study predictions and randomized to one of two classes, both called “Rejuvenating Movement” (such that they did not know if they were in the true QG/TCE group or the SQG gentle exercise group). Study staff involved in data collection and/or analysis were blinded to assignment.

2.3 Study Outcome measures

The exploratory outcomes were examined using the following tools. The 36-item Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form (known as the SF-36), was selected to measure two broad quality of life constructs, physical health and mental health.51 BMI was initially assessed as an eligibility criterion only, but after several participants in the first two cohorts of the QG/TCE intervention reported weight loss, BMI (as an exploratory outcome) was added to the list of outcome variables and was assessed post-intervention for the remaining 57 participants. Standard procedures for measuring height and weight were used for obtaining numbers to calculate BMI.

Cognitive function was measured using both self-report and objective performance tests. Cognitive function self-report was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function (FACT-COG), including 2 subscales, perceived cognitive impairment (PCI), and perceptions of effects of cognitive function on quality of life.52 Two brief measures of attention/working memory from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition, known as the WAIS-III53 were used: Digit Span and Letter-Number Sequencing with average reliability ratings of .90 and .82 respectively. These were used as objective, cognitive performance measures.

The Brief Physical Activity Questionnaire (BPAQ), adapted for use in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study, is a self-report instrument with high correlation to accelerometry (0.73) and comparable validity, sensitivity and measurement bias compared to the widely accepted Physical Activity Recall (PAR).54 This instrument was used to assess initial level of PA, determine high and low categories for stratification in the randomization process (based on prior data from a cohort of over 3000 in the WHI, establishing a mean of 8.4 MET/hours/week for fatigued breast cancer survivors)55 and to assess changes over time in PA.

2.4 Intervention, Process Control and Fidelity

A set of 10 QG/TCE exercises based on Tai Chi Easy56 practices (drawn from traditional forms of Tai Chi, but simplified and repeated for ease of learning), and a set of “Vitality Method” series of Qigong exercises57 were chosen based on the purported properties to improve overall Qi balance, vitality, and mental alertness, to be taught using the principles of Meditative Movement.19 These two practices, Tai Chi and Qigong have philosophical roots that are aligned, very similar in form when basic movements of each are simplified and repeated, and have been combined as “Tai Chi Easy”56 practice to reflect the principles of cultivating “Qi” through MM.19

A similar set of movements was selected from exercises designed for rehabilitation of breast cancer patients to be adapted for the SQG control intervention. For each QG/TCE movement selected, a similar movement was chosen for SQG, such as reaching with the arms upward, outwards, sideways, and in arcs; swaying and circling shoulders and hips; and slow, relaxed dance-like flowing movements alternating with a few muscle-tightening, isometric movements. A DVD was created for each, with demonstrations for performing each respective intervention. Both were labeled “Rejuvenating Movement”, and provided to participants for home practice.

Professionals experienced in leading exercise sessions with cancer patients taught both interventions. Sessions were sixty minutes long, delivered over 12 weeks, meeting twice a week for the first two weeks to provide the opportunity to learn the practices well, then once a week for the remainder of the period. Participants were asked to practice at home at least 30 minutes a day, 5 days per week and to keep a log of the frequency, minutes of practice and level of exertion.

To assess similarity on intensity and dose of the two interventions, the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (BRPE)58 and minutes practiced were recorded in participant logbooks. The BRPE ratings were nearly identical for the two interventions (QG/TCE 9.85, 2.20 SD and SQG 9.79, 2.98 SD) and total minutes practiced were not significantly different between the groups, (QG/TCE mean, 1290 minutes, 1106 SD; SQG 1194 minutes, 617 SD) indicating equivalence of intensity and dose. Using the Meditative Movement Inventory,59 scores for meditative focus were significantly different between the arms of the study (higher scores for QG/TCE), suggesting the intervention manipulation for SQG (i.e., similar movements as QG/TCE without the meditative focus) was effective. Additional detailed comparisons assessing intervention fidelity and manipulation checks may be accessed in the primary outcomes publication.37

2.5 Statistical Analysis Plan

This study was initially powered to detect a 0.75 effect size at power 85% for the primary outcome variable, fatigue (not reported here), assuming 30 participants in each of two groups after an expected attrition of 15%. Taking into account attrition, this study was not designed for an intention-to-treat plan for the primary or exploratory outcomes. Only individuals who attended some portion of the classes are included in the statistical analysis (irrespective of whether they had measurements at all three time points).

Baseline characteristics of the randomized participants were compared for the QG/TCE and SQG groups using two-sample independent t tests for continuous variables, and Fisher’s Exact tests for categorical variables. Normality was assessed using histograms and box plots.

Hierarchical linear models (linear mixed effects models) were used to assess the independent effects of intervention group (QC/TCE versus SQC) and time (3 time points: baseline, 12-week post-intervention, 3-month follow-up on outcomes other than BMI, only assessed at 2 time points). Since there were no statistically significant differences between the groups at baseline, analyses did not adjust for baseline demographic covariates. Missing values were not imputed due to the relatively small number of missing measurements (< 10%). Initially, the presence of an interaction between time and intervention was assessed using a likelihood ratio test. Such an interaction was observed (p < 0.05) only for BMI. When no interaction was observed, models with intervention group and time were estimated omitting the interaction terms. For all models, the SQG intervention group was considered the reference category. The baseline measurement was the reference value for time, with fixed effects for the post-intervention (and 3-month follow-up for those factors measured at that point). Computation of the SF36 summary standardized Physical Health and Mental Health scales was performed using the SF36 command in STATA 12.1, based on US data weights.51 All p-values were set at .05 for significance, are two-sided and unadjusted for multiple comparisons. STATA 12.1 was used for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1 Sample description

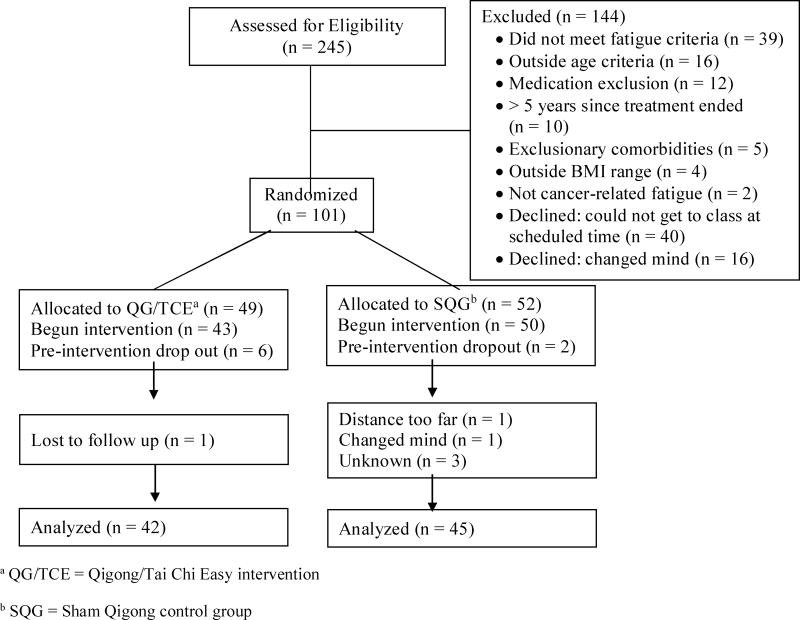

Two hundred and forty-five women were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 101 (41%) were eligible, consented to join the study and randomized. There were 14 dropouts prior to final data collection, leaving 87 completers with post-intervention data to evaluate for most variables (13.9% attrition)(Figure 1, Recruitment and Retention Flowchart). There were no significant differences between those who completed the study and those who dropped out on any of the outcomes.

Figure 1.

Participant Recruitment and Retention Flowchart

The mean age of participants was 59 years with a mean BMI of 26.8 kg/m2. Stage of cancer included Stage I (39.08%), Stage II (45.98%), and Stage III (3.45%). Participants were predominantly non-Hispanic white (with 2 Latinas, 3 Asian American, and 2 African American participants). There were no statistically significant differences in key baseline characteristics between the QC/TCE and SQG intervention groups (Table 1). No adverse events were reported in relationship to study interventions.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Arm of Study

| Combined (N = 87) | SQG (N = 45) | QG/TCE (N = 42) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | |||||

| Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | t (df) | p- valuea | |

| Age | 58.8 (8.94) | 59.8 (8.93) | 57.7 (8.94) | 1.06 (84) | 0.292 |

| Body Mass Index | 26.8 (4.49) | 26.6 (3.62) | 27.1 (5.33) | −0.43 (82) | 0.665 |

| Metabolic Equivalent of Task (METs) hrs./week | 11.7 (11.40) | 10.2 (10.58) | 13.3 (12.16) | −1.29 (84) | 0.201 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p- valueb | ||

| Estrogen Suppressive Therapy | 60 (68.97) | 30 (66.67) | 30 (71.43) | 0.639 | |

| Cancer Stage | |||||

| Stage 1 | 34 (39.08) | 20 (44.44) | 14 (33.33) | 0.722 | |

| Stage 2 | 40 (45.98) | 22 (48.89) | 18 (42.86) | ||

| Stage 3 | 3 ( 3.45) | 1 ( 2.22) | 2 ( 4.76) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Latino | 2 ( 2.30) | 1 ( 2.22) | 1 ( 2.38) | 1.000 | |

| Non Latino | 75 (86.21) | 40 (88.89) | 35 (83.33) | ||

| Race | |||||

| White | 79 (90.80) | 42 (93.33) | 37 (88.10) | 1.000 | |

| Other | 5 ( 5.75) | 3 ( 6.67) | 2 ( 4.76) | ||

| Household Income | |||||

| < $ 34,999 | 12 (13.79) | 10 (22.22) | 2 ( 4.76) | 0.121 | |

| $ 35,000 to $49,999 | 11 (12.64) | 8 (17.78) | 3 ( 7.14) | ||

| $ 50,000 to $74,999 | 14 (16.09) | 6 (13.33) | 8 (19.05) | ||

| $ 75,000 to $99,999 | 11 (12.64) | 5 (11.11) | 6 (14.29) | ||

| > $100,000 | 18 (20.69) | 8 (17.78) | 10 (23.81) | ||

| Highest Grade of Education | |||||

| High School or Less | 13 (14.94) | 7 (15.56) | 6 (14.29) | 0.746 | |

| Some College | 51 (58.62) | 25 (55.56) | 26 (61.90) | ||

| Post-graduate | 20 (22.99) | 12 (26.67) | 8 (19.05) |

p-value from two sample independent t test

p-value from Fisher’s Exact Test

3.2 Effectiveness of Intervention

Table 2 summarizes the changes in the self-reported measures between baseline and post-intervention, providing means and standard deviations. Significant changes across time (all p < 0.001) were observed for the Mental Health and Physical Health summary scales of the SF36 with no significant differences between the two interventions (both p > 0.10). Both groups demonstrated a statistically significant increase in their MET hours per week across time (p = 0.015, regression coefficient = 3.5), with no significant difference indicated between the two intervention groups (p = 0.18, regression coefficient = 3.2). Similar significant changes were observed across time for the FACT-COG components (both p < 0.001), also with no significant differences between the two intervention groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of SQC versus QC/TCE from Baseline to Post-Intervention for Self-report Exploratory Endpoints

| SQG Mean (SD) n |

QC/TCE Mean (SD) n |

Coefficients from hierarchical linear model (z statistic) p-value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-Intervention | Baseline | Post-Intervention | Intercept | Intervention | Time | |

| SF36 Physical Health Standarizeda | 42.9 (8.76) 45 |

48.2 (7.84) 45 |

40.4 (10.68) 41 |

47.7 (7.28) 39 |

42.58 (34.83) <0.001 |

−1.68 (−1.03) 0.305 |

5.95 (6.48) <0.001 |

| SF36 Mental Health Standarizeda | 44.6 (9.80) 45 |

50.7 (8.52) 45 |

43.2 (9.14) 41 |

51.5 (8.70) 39 |

44.11 (35.48) <0.001 |

−0.36 (−0.22) 0.826 |

7.08 (6.70) <0.001 |

| MET hours per weeka | 10.2 (10.58) 45 |

13.6 (11.82) 45 |

13.3 (12.16) 41 |

17.0 (16.83) 40 |

10.1 (5.67) <0.001 |

3.2 (1.36) 0.175 |

3.5 (2.44) 0.015 |

| FACT- Cog PCIa | 1.5 (0.85) 44 |

1.1 (0.75) 43 |

1.7 (0.72) 42 |

1.1 (0.66) 36 |

1.5 (14.18) <0.001 |

0.13 (0.85) 0.397 |

−0.48 (−7.24) <0.001 |

| FACT-Cog QOLa | 1.4 (1.05) 44 |

0.5 (0.72) 45 |

1.5 (1.04) 42 |

0.7 (0.93) 40 |

1.4 (10.74) <0.001 |

0.14 (0.84) 0.399 |

−0.85 (−7.45) <0.001 |

No statistically significant interaction between treatment and time. Therefore the coefficients for the model omitting the interaction term are reported

Objective, clinically measured outcomes are presented in Table 3. There was a statistically significant interaction between BMI change across time and the intervention groups (p = 0.048). Post-intervention, there was a statistically significant greater decrease in BMI (p = 0.048, regression coefficient = −0.66) for the QC/TCE group compared with the SQC group. The WAIS III letter number sequencing score demonstrated a significant change across time (p = 0.044; regression coefficient = 0.56), and there was a statistically significant difference in digit span score across time (p < 0.001; regression coefficient = −10.2). Neither cognitive performance measure differed significantly between groups (p = 0.48; regression coefficient = −0.36, and p = 0.87, regression coefficient = −0.11, respectively). Across all of these analyses, the mean changes were quite small between post-intervention and 3 month follow-up, and none demonstrated a statistically significant difference between the two intervention groups at the follow-up point (not shown). Thus, there is little evidence of loss of effect once the formal intervention ended and some time passed.

Table 3.

Comparison of SQC versus QC/TCE from Baseline to Post-Intervention for Clinically Measured Exploratory Outcomes: BMI and Cognitive Performance Tests

| SQG Mean (SD) n |

QC/TCE Mean (SD) n |

Coefficients from hierarchical linear model (z statistic) p-value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post- Intervention | Baseline | Post- Intervention | Intercept | Intervention | Time | Time by Intervention Interaction | |

| BMIa | 27.0 (4.68) 36 |

27.3 (4.73) 31 |

27.4 (5.54) 29 |

26.7 (5.28) 29 |

27.0 (32.06) <0.001 |

0.57 (0.46) 0.642 |

0.26 (1.15) 0.25 |

−0.66 (−2.00) 0.048 |

| Letter Number Sequencing Scoreb | 10.8 (2.16) 45 |

11.4 (3.21) 44 |

10.5 (2.80) 41 |

11.0 (2.42) 40 |

10.8 (29.10) <0.001 |

−0.36 (−0.71) 0.476 |

0.56 (2.02) 0.044 |

----- |

| Digit Span Scoreb | 17.9 (4.53) 45 |

7.3 (2.72) 44 |

17.3 (4.22) 41 |

7.7 (2.12) 40 |

17.6 (35.63) <0.001 |

−0.11 (−0.17) 0.869 |

−10.2 (−26.31) <0.001 |

----- |

Statistically significant interaction between treatment and time (p = 0.0484). Therefore the coefficient for the interaction term also is reported.

No statistically significant interaction between treatment and time. Therefore the coefficients for the model omitting the interaction term are reported

4. Discussion

The strengths of this study include (a) the double blind RCT design with a (b) “placebo” control group that separated effects of gentle movement from the meditative and breath focus aspects of the QG/TCE intervention and (c) the use of validated instruments to measure study outcomes. The two interventions (QG/TCE and SQG), both called “Rejuvenating Movement” and both involving gentle, low-intensity exercise, showed significant impacts on the exploratory outcomes: breast cancer survivors’ physical and mental QOL; cognitive function and performance; and overall levels of PA (METs). There is already a strong body of literature regarding QOL as an outcome in MM studies with cancer patients and survivors, including significant improvements among cancer patients practicing Medical Qigong 42 and a number of studies have shown yoga to improve QOL specifically for breast cancer patients and survivors38-41. But as noted before, TC and Qigong interventions have been less studied with BCSs. Given that our results showed improvements over time for both interventions, it would be useful to test TCE/QG against an inactive control group (e.g., attention, or education only) to detect significant changes, if they exist.

Physical activity

With the preponderance of persistent symptoms and difficulty with managing weight in this population, it is important to explore a variety of options that may appeal to different women’s motivational profiles. It appears that both a meditative movement intervention and a low-intensity (non-meditative) PA program may be helpful to get women back to moving, bridging from a sedentary lifestyle to more activity (as evidenced by the significant improvements over time for both groups), and that these forms of gentle movement may help with physical and psychological symptoms that continue past the time of treatment. Interestingly, overall levels of activity (MET/hour/week) increased in response to both interventions, and were maintained at the 3-month post-intervention point, well after the ending of the weekly classes and weekly phone calls to encourage continued practice. In addition, physical and mental health aspects of QOL and cognitive function (both known to respond to more moderate forms of PA) also improved over time for both groups, a new finding in this study.

Other outcomes

The trend in this exploratory analysis was for each of the assessed outcomes to be improved significantly over time with both interventions, and non-significantly, but consistently, more improvement for QG/TCE than SQG. Only one of the exploratory outcomes, BMI, achieved significant improvements for QG/TCE compared to the SQG control. The BMI change in the QG/TCE brought women from a mean of 27.1 to 26.7 (closer to a normal weight standard of BMI < 25) while those in the SQG group continued to increase BMI. Our QG/TCE intervention with the accompanying focus on breath and meditative states to create a deep sense of relaxation, suggested an advantage over simple PA, providing support for weight loss (even though this was not with participants as a stated goal of the intervention). The low level of exertion that was reported in the BRPE suggests that there may be other factors besides PA that may be activating this weight difference between groups.

Very little research has addressed the potential of MM to influence body composition among BCSs. One study showed no weight loss, but decreased body fat and increased muscle mass for BCSs practicing yoga, indicating positive body composition changes,60 but otherwise this has not been a topic of much research.

A recently published model suggesting how weight change may occur with MM in BCSs describes pathways of cognitive, emotional, eating behavior and metabolic shifts associated with reducing stress.11. Limited options for weight loss among this group of survivors suggests a need for creative solutions to encouraging this important lifestyle-related behavior change, the finding that women practicing QG/TCE may reduce BMI compared to those doing gentle exercise without meditation and breath focus warrants further investigation. As noted, the current state of the science has mixed results on whether or not MM practices may act to facilitate weight loss. It would be important to develop a better understanding of the possible mechanisms for weight loss and incorporate such theoretical models into future research to better understand the conditions under which weight loss may or may not occur.

Limitations

This study was designed to be a pilot assessment of the effects of MM on various factors associated with fatigue and other symptoms in breast cancer survivors, with the current report addressing a number of exploratory outcomes. Interpretation of results on pilot studies are necessarily cautious with greater room for error using smaller sample sizes and more relaxed standards for study design elements61 (including suspension of intent-to-treat analysis). The interpretation of the significant results, both for the comparison between intervention results for BMI and for the pre- to post results observed in both interventions, should be regarded with caution.

Given the non-significant differences between the SQG and QG/TCE interventions on most of the exploratory outcomes examined, it would be important to re-examine sample size and power, as well as comparison group choices for future studies. Of course, it is possible that there simply is not enough of a difference for the meditative state and breath focus of the QG/TCE intervention to influence QOL and cognitive function beyond what gentle exercise may do. Conversely, these factors may take longer or require a less active control group condition to demonstrate change to the degree that statistical significance may be seen. An essential study design feature recommended in recent CAM research guidelines suggests three-arm designs (intervention arm, placebo control arm and usual care control arm) rather than the two arms used in conventional medicine studies (intervention arm, placebo control arm) so as to better separate effects of the tested intervention.62 Confirming the specific effects of QG/TCE may require a no-intervention/usual care (e.g., a wait list) or an attention control group as well as a sham control.

5. Conclusions

Both intervention groups, QG/TCE and SQG, produced significant improvements over time. Our findings suggest that these gentle exercises may provide initial and short-term continuing benefits for overcoming numerous symptoms in breast cancer survivors and may help bridge the gap between inactivity and becoming physically active. Low-intensity exercises should be further tested before proceeding to recommendations for recovery from symptoms that persist for breast cancer survivors well past the window of treatment. For survivors with persistent fatigue and reduced activity levels, beginning with gentle exercise may be a feasible way to move past sedentariness and slowly shift to a more active lifestyle.

Moreover, for the smaller number of participants (n = 57, added after the first two cohorts completed) who were assessed for BMI, it appears that the QG/TCE practice designed to cultivate “Qi” (defined as vital energy or life force in Traditional Chinese Medicine) may help reduce BMI compared to the SQG exercises. With no instruction for nutritional changes, nor a goal set for reducing BMI, this finding suggests areas to explore, including how MM may indirectly affect emotional states, metabolic shifts, and related eating behaviors that may make a difference in weight loss. The current positive findings suggest the need for further evaluation of QG/TCE, and the mechanisms by which it may reduce BMI and other symptoms.

Highlights.

Qigong/Tai Chi Easy (QG/TCE) and gentle exercise improve quality of life in breast cancer survivors.

QG/TCE and gentle exercise improve cognitive function and increase physical activity in BCSs.

QG/TCE may play a role in weight reduction in BCSs.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Office of Women’s Health) grant number 5 U01 AT002706-03 and the Arizona Cancer Center Support Grant (P50 CA023074) . Scottsdale Healthcare Shea Medical Center and the Virginia G. Piper Cancer Center provided additional support.

Funding Source: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Office of Women’s Health) grant number 5 U01 AT002706-03 and the Arizona Cancer Center Support Grant (P50 CA023074) . Scottsdale Healthcare Shea Medical Center and the Virginia G. Piper Cancer Center provided additional support.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. Estimated US cancer prevalence counts: Who are our cancer survivors in the U.S.? [Accessed September 12, 2011];Cancer Survivorship Research: Cancer Control and Population Sciences Web site. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/statistics/statistics.html. Updated Accessed September 12, 2014.

- 2.Epplein M, Zheng Y, Zheng W, et al. Quality of life after breast cancer diagnosis and survival. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(4):406–412. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavalli Kluthcovsky A, Urbanetz A, Carvalho D, Pereira Maluf E, Schlickmann Sylvestre G, Bonatto Hatschbach S. Fatigue after treatment in breast cancer survivors: Prevalence, determinants and impact on health-related quality of life. Supportive care in cancer. 2012;20(8):1901. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, Todd BL, Feuerstein M. It's not over when it's over: Long-term symptoms in cancer survivors—a systematic review. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2010;40(2):163–181. doi: 10.2190/PM.40.2.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vance V, Mourtzakis M, McCargar L, Hanning R. Weight gain in breast cancer survivors: Prevalence, pattern and health consequences. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(4):282–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donovan KKA. Course of fatigue in women receiving chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy for early stage breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(4):373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cella DD. Fatigue in cancer patients compared with fatigue in the general United States population. Cancer. 2002;94(2):528–538. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kjaer TK, Johansen C, Ibfelt E, et al. Impact of symptom burden on health related quality of life of cancer survivors in a Danish cancer rehabilitation program: A longitudinal study. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(2):223–232. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.530689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan JL, Carroll JK, Ryan EP, Mustian KM, Fiscella K, Morrow GR. Mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue. Oncologist. 2007;12(Supplement 1):22–34. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Kwan L, Breen EC, Cole SW. Inflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: Do fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism? Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(26):3517–3522. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larkey LK, Vega-López S, Keller C, et al. A biobehavioral model of weight loss associated with meditative movement practice among breast cancer survivors. Health Psychology Open. 2014;1(1) doi: 10.1177/2055102914565495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demark-Wahnefried W, Rimer BK, Winer EP. Weight gain in women diagnosed with breast cancer. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97(5):519–529. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(97)00133-8. quiz 527–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heideman W, Russell N, Gundy C, Rookus M, Voskuil D. The frequency, magnitude and timing of post-diagnosis body weight gain in Dutch breast cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(1):119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagaiah G, Hazard HW, Abraham J. Role of obesity and exercise in breast cancer survivors. Oncology. 2010;24(4):342–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ewertz M, Jensen MB, Gunnarsdóttir KÁ, et al. Effect of obesity on prognosis after early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(1):25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patterson RE, Cadmus LA, Emond JA, Pierce JP. Physical activity, diet, adiposity and female breast cancer prognosis: A review of the epidemiologic literature. Maturitas. 2010;66(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elkins G, Fisher W, Johnson A. Mind–body therapies in integrative oncology. Current treatment options in oncology. 2010;11(3–4):128–140. doi: 10.1007/s11864-010-0129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson LE. Meditation and yoga. In: Holland JC, Breitbart WS, Jacobsen PB, Lederberg MS, Loscalzo MJ, McCorkle R, editors. Psycho-oncology. 2. USA: Oxford Univ Pr; 2010. p. 429. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larkey L, Jahnke R, Etnier J, Gonzalez J. Meditative movement as a category of exercise: Implications for research. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(2):230–238. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng Y, Luo T, Xie H, Huang M, Cheng AS. Health benefits of qigong or tai chi for cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(1):173–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campo RA, Agarwal N, LaStayo PC, et al. Levels of fatigue and distress in senior prostate cancer survivors enrolled in a 12-week randomized controlled trial of qigong. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(1):60–69. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0315-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan Y, Yang K, Shi X, Liang H, Zhang F, Lv Q. Tai chi chuan exercise for patients with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:535237. doi: 10.1155/2015/535237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang GY, Wang LQ, Ren J, et al. Evidence base of clinical studies on tai chi: A bibliometric analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robins JL, Elswick RK, McCain NL. The story of the evolution of a unique tai chi form: Origins, philosophy, and research. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(3):134–146. doi: 10.1177/0898010111429850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z, Meng Z, Milbury K, et al. Qigong improves quality of life in women undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2013;119(9):1690–1698. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelley GA, Kelley KS. Meditative movement therapies and health-related quality-of-life in adults: A systematic review of meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang G, Wang S, Jiang P, Zeng C. Effect of yoga on cancer related fatigue in breast cancer patients with chemotherapy. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2014;39(10):1077–1082. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mustian KM. Yoga as treatment for insomnia among cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review. Eur Med J Oncol. 2013;1:106–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Janelsins M, et al. Multicenter, randomized controlled trial of yoga for sleep quality among cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(26):3233–3241. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mustian KM, Janelsins M, Peppone LJ, Kamen C. Yoga for the treatment of insomnia among cancer patients: Evidence, mechanisms of action, and clinical recommendations. Oncol Hematol Rev. 2014;10(2):164–168. doi: 10.17925/ohr.2014.10.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andysz A, Merecz D, Wojcik A, Swiatkowska B, Sierocka K, Najder A. Effect of a 10-week yoga programme on the quality of life of women after breast cancer surgery. Prz Menopauzalny. 2014;13(3):186–193. doi: 10.5114/pm.2014.43823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janelsins MC, Davis PG, Wideman L, et al. Effects of tai chi chuan on insulin and cytokine levels in a randomized controlled pilot study on breast cancer survivors. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2011;11(3):161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carson JW, Carson KM, Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Seewaldt VL. Yoga of awareness program for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: Results from a randomized trial. Supportive care in cancer. 2009;17(10):1301–1309. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rausch SM, Robins Jolynne Walter JM, McCain NL. Tai chi as biobehavioral intervention for women with breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2006;20:e58–e59. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Danhauer SC, Mihalko SL, Russell GB, et al. Restorative yoga for women with breast cancer: Findings from a randomized pilot study. Psychooncology. 2009;18(4):360–368. doi: 10.1002/pon.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, et al. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118(15):3766–3775. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larkey LK, Roe DJ, Weihs KL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of Qigong/Tai chi easy on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2014:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9645-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moadel AB, Shah C, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of yoga among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: Effects on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4387–4395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Speed-Andrews AE, Stevinson C, Belanger LJ, Mirus JJ, Courneya KS. Pilot evaluation of an iyengar yoga program for breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(5):369–381. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181cfb55a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chandwani KD, Perkins G, Nagendra HR, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of yoga in women with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(10):1058–1065. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vadiraja HS, Raghavendra RM, Nagarathna R, et al. Effects of a yoga program on cortisol rhythm and mood states in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8(1):37–46. doi: 10.1177/1534735409331456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oh B, Butow PN, Mullan BA, et al. Effect of medical qigong on cognitive function, quality of life, and a biomarker of inflammation in cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20(6):1235–1242. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biegler KA, Alejandro Chaoul M, Cohen L. Cancer, cognitive impairment, and meditation. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(1):18–26. doi: 10.1080/02841860802415535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wayne PM, Walsh JN, Taylor-Piliae RE, et al. Effect of tai chi on cognitive performance in older adults: Systematic review and meta–analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(1):25–39. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen SC, Ueng KC, Lee SH, Sun KT, Lee MC. Effect of t'ai chi exercise on biochemical profiles and oxidative stress indicators in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(11):1153–1159. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu X, Miller YD, Burton NW, Chang JH, Brown WJ. Qi-gong mind-body therapy and diabetes control. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manchanda SC, Narang R, Reddy KS, et al. Retardation of coronary atherosclerosis with yoga lifestyle intervention. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48(7):687–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown L, Kroenke K, Theobald D, Wu J. Comparison of SF-36 vitality scale and fatigue symptom inventory in assessing cancer-related fatigue. Supportive care in cancer. 2011;19(8):1255. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Jones LW. Coping with cancer: Can exercise help? The Physician and sportsmedicine. 2000;28(5):49–58. doi: 10.3810/psm.2000.05.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. Sf-36 physical & mental health summary scales: A user's manual. Health Assessment Lab; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobs SR, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M, Wagner LI, Anasetti C. Evaluation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy cognitive scale with hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wechsler D. WAIS-III administration and scoring manual. 3. Psychological Corp; 1997. p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson-Kozlow M, Rock CL, Gilpin EA, Hollenbach KA, Pierce JP. Validation of the WHI brief physical activity questionnaire among women diagnosed with breast cancer. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(2):193–202. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hong S, Bardwell WA, Natarajan L, et al. Correlates of physical activity level in breast cancer survivors participating in the Women’s healthy eating and living (WHEL) study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;101(2):225–232. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9284-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jahnke RA, Larkey LK, Rogers C. Dissemination and benefits of a replicable tai chi and qigong program for older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31(4):272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jahnke R. The healer within: Using traditional Chinese techniques to release your body's own medicine. San Francisco: HarperOne; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Borg G. Borg's perceived exertion and pain scales. Human Kinetics; 1998. http://books.google.com/books?id=MfHLKHXXlKAC. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Larkey LK, Szalacha LA, Rogers CE, Jahnke RA, Ainsworth B. Development and validation of the meditative movement inventory (MMI) Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2012;20(3):230–243. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.20.3.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Long Parma D, Hughes DC, Ghosh S, et al. Effects of six months of yoga on inflammatory serum markers prognostic of recurrence risk in breast cancer survivors. Springerplus. 2015;4 doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-0912-z. 143-015-0912-z. eCollection 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carter RE, Woolson RF. Statistical design considerations for pilot studies transitioning therapies from the bench to the bedside. J Transl Med. 2004;2(1):37. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-2-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yeh GY, Kaptchuk TJ, Shmerling RH. Prescribing tai chi for fibromyalgia--are we there yet? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):783–784. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1006315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]