Abstract

Identifying appropriate molecular targets is a critical step in drug development. Despite many advantages, the traditional tools of observational epidemiology and cellular or animal models of disease can be misleading in identifying causal pathways likely to lead to successful therapeutics. Here we review some favorable aspects of human genetics studies that have the potential to accelerate drug target discovery. These include using genetic studies to identify pathways relevant to human disease, leveraging human genetics to discern causal relationships between biomarkers and disease, and studying genetic variation in humans to predict the potential efficacy and safety of inhibitory compounds aimed at molecular targets. We present some examples taken from studies of plasma lipids and coronary artery disease to highlight how human genetics can accelerate therapeutics development.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States[1] despite significant advances in our understanding of human biology and pathophysiology. The cost of developing novel pharmaceuticals to treat CVD is staggering; the average cost to bring a new therapeutic drug from target identification to market is nearly 2 billion dollars[2]. Amortizing late stage failures is a significant but under-appreciated burden contained in these costs; nearly 80% of compounds entering phase II clinical trials will fail to reach regulatory approval, largely due to a lack of efficacy or an unacceptable safety profile[2]. This is a particularly remarkable failure rate in the context of the preclinical data needed to initiate a phase II clinical trial, indicating that animal and cellular models of human disease are often inadequate predictors of what will ultimately emerge as a successful therapeutic target.

The study of naturally occurring human genetic variation has the potential to accelerate the development of successful CVD therapeutics through several avenues (Table 1). First, genetic studies can identify causal pathways for disease. To varying degrees, both Mendelian and complex genetic diseases result from the interplay of DNA changes and environment. Identifying the heritable component of disease has successfully identified causal pathways, existing drug targets, and novel therapeutic avenues in a variety of cardiovascular disorders. Second, genetic studies can identify biomarkers that are causally related to – and not merely correlated with – disease. Unlike the correlations between biomarkers and disease commonly identified through observational epidemiologic studies, genetic variation has unique properties that allow for the identification of causal relationships. Identifying causality is paramount in drug development, as therapeutically manipulating non-causal biomarkers will not alter disease. Third, studies of humans with naturally occurring-genetic variation – particularly those with loss-of-function alleles – in genes encoding drug targets can provide a unique insight into the potential efficacy and safety of therapeutic modulation using that drug. Broadly considered as phenotype screens, these approaches seem to be more likely to yield successful drugs than target-based approaches[3]. Here, we review these concepts in discussing the potential of human genetics to provide clinically meaningful insights for drug target discovery.

Table 1.

Human genetic study designs with potential utility in drug target discovery

| Study type | Class of genetic variation studied | Typical analysis | Typical use | Selected examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic association study | Common variants through genotyping | Identify genetic variation with significantly different frequency in cases with disease compared to disease-free controls | Discover novel genetic loci and pathways underlying disease | GWAS for CHD ([41], [10], [42], [43], [44], [45], among others) GWAS for Lipids ([8], [46], [47], among others) GWAS for blood pressure ([48], [49], [50], among others) GWAS for atrial fibrillation ([51], [52], [53], among others) GWAS for rheumatoid arthritis ([54, 55], among others) |

|

|

|

|||

| Rare variants through genotyping or sequencing | Discover novel genes and pathways underlying disease |

LDLR and APOA5 for CHD [6] TM6SF2 for cholesterol and CHD [56] MYL4 for atrial fibrillation[57] SCN11A and pain perception[58] FBN1 and Marfan's syndrome [58] |

||

|

| ||||

| Mendelian Randomization Study | Typically common variants | Test for association between genetic variants that alter biomarkers and disease. | Identify causal relationships between biomarkers and disease | HDL and CHD [16] Lp-PLA2 and CHD [22], [59] sPLA2 and CHD [21] CRP and CHD [60] |

|

| ||||

| Loss of function studies | Rare loss of function alleles | Identify individuals carrying loss of function alleles in a drug target. Test for association with phenotypes (disease endpoints or biomarkers). | Estimate therapeutic effect (and potentially safety) of inhibitory drugs targeting gene of study |

APP and Alzheimer's disease [61] APOC3 and CHD [30, 31] NPC1L1 and CHD [33] PCSK9 and CHD [29] SLC30A8 and type 2 diabetes [62] |

GWAS=Genome-wide association studies

Validated targets: Human genetics reveals pathways underlying human disease

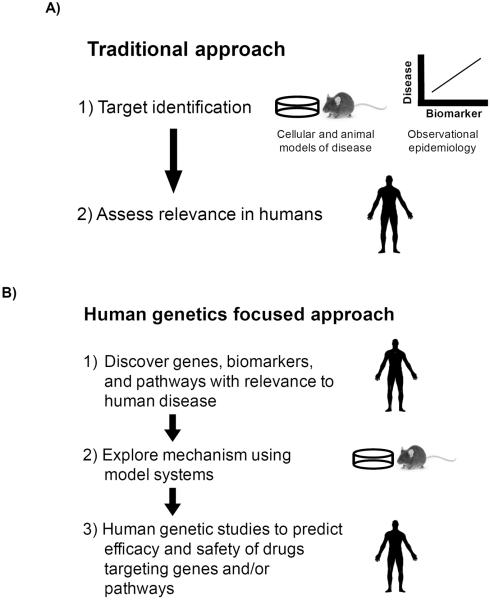

Potential therapeutic targets often emerge from the results of experiments in cellular or animal models of human disease (Figure 1A). However, the vast majority of drugs entering clinical trials in humans will fail to reach regulatory approval. Why do these compounds fail? Some of these failures are due to the inability of cellular and animal models to faithfully discover pathways underlying the disease in humans. Human genetic studies, on the other hand, have a distinct advantage over cellular and animal models: the experiments are carried out in humans and resulting observations are by their very nature directly relevant to human disease. Thus, we now have the ability to reverse the typical research cycle; instead of discovering mechanisms in model organisms and then testing to see if those are relevant to human disease, human genetic studies provide a means to first discover genes and pathways relevant to human disease and then return to model organisms to explore the underlying mechanisms (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Using human genetics as a tool to guide drug target discovery. A) Traditional approach to target identification begins with discovering mechanisms and biomarkers prior to validating their role in human disease. B) A human genetics guided approach begins with discovering genes, biomarkers, and pathways implicated in human disease.

Studies of families exhibiting Mendelian inheritance of CVD or associated risk factors were among the first genetic experiments that provided direct evidence of causal pathways underlying human disease. In 1986, Brown and Goldstein first identified mutations in the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) as the genetic etiology of familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). Since their initial discovery, more than 1,000 LDLR alleles have been identified, each typically observed in a small number of individuals with FH[4]. Despite the rarity with which these mutations occur, two key observations emerge from Mendelian studies of human disease. First, the identification of causal genes for Mendelian cardiovascular disease has led to fundamental insights into human biology and spurred the development of novel therapeutics (recently reviewed in [5]). For example, Brown and Goldstein's work on the genetic basis of FH unraveled the basic biochemistry of cholesterol metabolism in humans and solidified HMGCoA reductase (the rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis) as a therapeutic target (later successfully inhibited with the statin class of medications). Second, although these mutations may be individually rare, their collective burden in disease can be significant. We recently discovered that approximately 1:200 individuals carry a rare LDLR mutation and have hypercholesterolemia[6], significantly higher than the historical FH prevalence estimate of 1:500[7]. Furthermore, we found that approximately 2% of individuals with myocardial infarction at an early age harbor a rare deleterious mutation in LDLR[6], supporting the notion that individually rare mutations can have a significant impact in the population.

More recent advances in human genetics (e.g. cost effective genome-wide interrogations and very large DNA collections in appropriately phenotyped subjects) have enabled population-scale association studies for diseases exhibiting complex inheritance. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been performed for many forms of CVD[5] and have successfully revealed known and novel therapeutic targets. For example, a common intronic mutation in the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase gene (HMGCR), the molecular target of the statin class of medications, is robustly associated with plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) concentrations[8]. Although associated with a very modest change in LDL concentration at the population level (~1.5 mg/dl), the association between genetic variation in this locus and phenotype points to a pathway relevant to lipoprotein metabolism in humans. A recent study examining the results of 361 GWASs found 63 instances in which the GWAS results pointed to a gene encoding a drug target for a therapeutic compound developed for the same disease[9]. The same study also found 92 instances in which the GWAS result pointed to a drug target that had an indication that was different than the original GWAS disease study, indicating a potential for therapeutic repurposing. Another demonstration of the potential for therapeutic repurposing came from a 2014 study that demonstrated GWAS loci for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) contained not only genes that were targets of approved therapies for RA but also genes that were targets of drugs developed for other indications. Genetic studies can also point to novel therapeutic pathways. Of the 46 genetic loci robustly associated with risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), approximately two-thirds appear to associate with CHD independently of known risk factors[10]. Further functional studies may reveal “druggable” targets in a number of these loci.

Biomarker X is associated with disease Y, but does X cause Y?: Human genetics as a means of assessing causality

Over the last 65 years, observational epidemiology studies such as the Framingham Heart Study have led to numerous important insights into the epidemiology of risk factors and cardiovascular disease[11]. For example, over half a century ago, Framingham investigators identified elevated blood pressure and plasma cholesterol as “factors of risk” (a term Framingham investigators originated and which sparked the field of “risk factor” studies) for the development of CHD[12]. Despite many strengths, however, observational epidemiology cannot distinguish cause from mere correlation for any pairing of biomarker with disease.

A recent example highlights this limitation as well as the consequences of assuming causality based on observational epidemiology. For decades, a robust inverse association of plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) with CHD has been noted. Across multiple epidemiologic cohorts, a 1 mg/dl increase in HDL concentration has been correlated with approximately 1.5% decreased risk of CHD. Yet despite this robust association, multiple attempts at therapeutically raising HDL have failed to demonstrate reduction in risk of CHD[13, 14]. One interpretation of these failed trials is that HDL is not causal and instead merely correlated with disease and that modulating levels will have little impact on modifying disease risk.

Why is it difficult to determine which associations from observational epidemiology are causal? Observational studies are inherently prone to several avenues of confounding and bias that limit the ability to draw causal inferences. First, it is difficult to fully account for all potential confounders. Confounding factors are those that independently associate with both the biomarker and disease, thus inducing an observed association between the two entities even when no causal role exists. A simple example is the positive correlation between grey hair and risk for CHD. A robust association can be identified between this biomarker (hair color) and disease despite a relationship that is obviously not causal. Instead, a confounder (aging) induces the association due to a strong relationship with both entities. It is obviously critical to identify causal relationships since treating grey hair (through cutting or coloring) is not expected to reduce the incidence of CHD. Another, subtler confounding occurs when the disease process itself modifies the biomarker, resulting in reverse causation. For example, the presence of calcium in the coronary arterial wall is positively correlated with atherosclerosis; however, the calcium itself does not lead to atherosclerosis but rather it is a result of the disease process. Finally, various forms of bias can influence observed relationships in epidemiologic studies.

In humans, the current gold standard to prove causality between biomarker and disease is a randomized control trial (RCT). In this type of study design, individuals are randomized to receive an intervention that modifies the biomarker and are prospectively assessed for the development of disease. If truly assigned randomly, the intervention will be allocated independently of any potential confounding factors, and reverse causation is eliminated by prospectively assessing risk of disease after allocating treatment. The obvious downside to RCTs is their significant cost and time, reaching into hundreds of millions of dollars often with years of follow-up.

Several aspects of human genetic variation mimic attractive attributes of an RCT, suggesting they might be useful in assessing causal relationships. Genetic variants are randomly allocated at meiosis, and due to Mendel's second law (that genes are inherited independently of one another), are not correlated with other potential confounding factors[15]. In addition, inherited genetic variation is present at birth and remains unchanged throughout life without being modified by any disease process, eliminating the possibly of reverse causation. Through population studies, genetic markers have been identified that robustly associate with the level of various biomarkers. If the biomarker is indeed casual for disease, then genetic variation associated with biomarker level should also be correlated with presence of disease.

Mendelian randomization is a human genetics approach where a genetic variant (or multiple variants) is used as an instrumental variable to assess the causal relationship between biomarker and disease. In this type of study, genetic variation that affects the level of the biomarker is first identified. The level of biomarker change associated with the genetic variation is then determined. Individuals in the population who carry this genetic variation can be thought of as taking a `drug' that alters the biomarker by this level throughout their life. The outcome between genetic variation and disease is then studied and compared with what would be expected from observational epidemiology based on the degree of biomarker change. As an example, we recently conducted a Mendelian randomization study that began by identifying genetic variation that was correlated with changes in LDL cholesterol [16]. Across multiple genes, the genetic variant that was associated with higher LDL cholesterol was also associated with increased risk of CHD. Using a score that summarized the effects of the LDL cholesterol associated variants, individuals who had a one standard deviation increase (~35 mg/dl) in the biomarker (i.e. LDL cholesterol) had more than twice the risk of CHD compared with non-carriers, a result that even exceeded the predicted effect based on observational epidemiology. Similarly to LDL cholesterol, a set of genetic variants were identified that correlated with change in HDL cholesterol concentration. In contrast to LDL cholesterol, however, across both individual variants and a score summarizing multiple variants, individuals who had a genetically induced one standard deviation increase (~15 mg/dl) in the biomarker (i.e. HDL cholesterol) had no difference in risk of CHD. These results suggest that the relationship between HDL cholesterol and CHD is correlated but not causal. As mentioned above, failed clinical efforts at modulating CHD risk using HDL modifying agents also support this notion.

Similarly, three very large clinical trials focused on reducing the activity of either secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) or lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2) [17, 18],[19] failed to demonstrate any clinical benefit despite epidemiologic findings that higher biomarker levels were correlated with increased risk of CHD[20]. In Mendelian randomization analyses, gene variants that increase sPLA2 or Lp-PLA2 activity do not increase risk for CHD [21], [22], arguing against a causal relationship of either sPLA2 or Lp-PLA2 with CHD. As such, these genetic studies anticipate that therapies focused on these targets are not likely to be effective.

Several assumptions are made during Mendelian randomization analysis and validity of study conclusions is dependent on these assumptions. First, the gene variant should be robustly associated with the biomarker. When gene variants have modest effects on the biomarker (so-called `weak instrument' bias), the absence of association with disease may be due to insufficient statistical power. Second, the gene variant is not associated with other confounding factors (for example, an association with both cholesterol and smoking). Third, the genotype is assumed to lead to disease exclusively through the biomarker being studied; as such, the gene variant should not exhibit relationships to multiple intermediate biomarkers (e.g., should not exhibit pleiotropy). Of note, newer methods in development may be robust to this assumption.

Reverse genetics: Human genetics yields insights into likelihood of therapeutic efficacy and potential adverse effects

Due to the historical expense and difficulty of conducting large-scale DNA sequencing experiments, human genetic studies have typically been conducted as `forward' genetic screens. A traditional forward screen begins by ascertaining individuals based a disease of interest. Using a variety of genetic techniques, the goal is then to discover the molecular basis underlying the phenotype. While this technique has been fruitful in identifying thousands of genetic factors underlying human diseases and traits[23], this type of design is inherently predisposed to ascertainment bias (i.e. a systematic difference between what is observed in a sample and the true population due to the method of data collection). Technological advances in DNA sequencing and genotyping now allow investigators to `reverse' the experimental design. In a reverse screen, individuals are ascertained based on a genotype of interest (not a disease) and a variety of techniques can be employed to discover the full spectrum of phenotypic consequences that are associated with the specific genetic change.

Some naturally occurring human genetic variation leads to gene inactivation. These changes can range from a whole or partial gene deletion to a single nucleotide substitution that either introduces a premature stop codon or induces aberrant pre-mRNA splicing leading to a defective gene product. These inactivating (also termed `loss of function', `null', or `protein-truncating') mutations are often very rare in the population due to the effects of purifying selection (the evolutionary process that selectively removes deleterious alleles due to lower fitness) and can lead to a substantial phenotypic effect. Naturally occurring DNA changes that lead to loss of function in genes encoding drug targets can be thought of as reagents in an “experiment of nature”[24]. Due to genetically inactivating a drug target, these mutations simulate lifelong exposure to an inhibitory drug. When used as the basis of a reverse genetic screen, these mutations can be used to infer the potential clinical efficacy and potential side effects associated with a drug. With advances in DNA sequencing technology, screening very large studies to identify inactivating mutation carriers in potential drug targets is now practical, providing investigators with the opportunity to establish that loss of gene function over a lifetime both confers protection from disease and is tolerated.

The proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) gene was first identified as regulating plasma LDL cholesterol when a forward genetic screen in 2003 identified gain of function mutations in PCSK9 as a cause of autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia[25]. A subsequent series of human reverse genetic experiments solidified PCSK9's potential role as a therapeutic target. First, loss of function mutations were identified that associated with low levels of LDL cholesterol[26, 27], confirming the expected in vivo biological response to loss of gene function. In addition, individuals with partial and complete loss of PCSK9 were found to be without adverse consequences, supporting the hypothesis that PCSK9 inhibition would be tolerated[28]. Finally, loss of function mutations in PCSK9 were found to associate with not only lower LDL cholesterol but also lower risk of CHD[29], supporting the hypothesis that PCSK9 is an appropriate drug target to reduce clinical disease. This series of human genetic experiments accelerated the development of PCSK9 from target identification[25] to an approved therapy in 12 years[28, 29].

We and others have recently demonstrated similar results for loss of function variants in the APOC3 gene[30, 31]. APOC3 functions to inhibit lipoprotein lipase (LPL), a key regulator of plasma triglyceride and HDL concentrations. Individuals who carry a loss-of-function mutation in APOC3 would be expected to have increased LPL activity (due to loss of APOC3 inhibition) and the increased LPL activity would be expected to result in lower triglycerides. We and others found that individuals carrying mutations that disrupt APOC3 have approximately 40% lower triglycerides and also 40% lower risk of CHD. These studies contribute to a growing body of literature that support the hypothesis that triglycerides are causally related to CHD[32], and that therapeutics focused on stimulating the lipoprotein lipase pathway (either through increasing LPL activity or by inhibiting APOC3) may prove to be beneficial in preventing clinical CHD.

We used a similar approach to demonstrate that loss-of-function mutations in the NPC1L1 gene were associated with protection from CHD[33]. Ezetimibe, a non-statin therapeutic agent approved for lowering cholesterol, inhibits the protein product of NPC1L1. Despite its ability to reduce plasma cholesterol levels, there was substantial uncertainty over whether or not ezetimibe would reduce clinical CHD[34, 35]. To estimate the clinical effect of inhibiting NPC1L1, we designed a human genetics experiment in which we sequenced the coding regions of NPC1L1 to identify individuals who carried loss-of-function alleles. Approximately 1 in every 650 individuals carry a loss-of-function allele in NPC1L1 and provide a unique insight into the lifelong effects of having one copy of NPC1L1 inactivated. We demonstrated that these individuals, when compared with those who did not carry NPC1L1 inactivating mutations, had approximately 12 mg/dl lower LDL cholesterol and 53% reduced risk of CHD[33]. As might be predicted by the human genetic study, therapeutic inhibition of NPC1L1 with ezetimibe was later shown to both lower LDL cholesterol and reduce CHD risk in a large randomized control trial[36]. Despite similar reductions in the levels of LDL cholesterol, inactivating NPC1L1 mutations were associated with a much larger magnitude of CHD reduction (53%) compared with ezetimibe (13% reduction in any myocardial infarction). This difference, presumably reflecting the effects of lifelong LDL lowering due to genetic causes compared to only a few years in a clinical trial, has been observed across a range of genetic mechanisms[37]. Although our examples here focus largely on plasma lipids and CHD, there are other successes across a variety of human diseases (see Table 1 for selected examples).

Genetic studies can also provide insight into some of the potential adverse effects of manipulating drug targets. For example, an association between statin use and increased risk of type 2 diabetes has long been observed[38]. Recently, Swerdlow and colleages presented data from a large meta-analysis finding that genetic variants in HMGCR (the gene encoding the target of statin medications) associated with decreased LDL cholesterol were simultaneously associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes. This observation suggests that the increased risk of type 2 diabetes associated with statin use is due to an “on-target” effect (i.e. the increased diabetes risk is due to the drug inhibiting its target and not from some other off-target effect) and that further attempts to make statins more specific in an attempt to reduce diabetes risk may be futile[39]. Importantly, the same genetic variants associated with lower LDL cholesterol and increased risk of type 2 diabetes in HMGCR are associated with reduced risk of CHD (summary data obtained from the CARDIoGRAM Consortium at http://www.cardiogramplusc4d.org/downloads/), suggesting the net effect of HMGCR inhibition protects against CHD despite an increased risk of diabetes. Human genetics can also provide insight into the genetic basis of adverse drug effects unrelated to the drug's target. For example, a genome-wide association study identified polymorphisms in the gene SLCO1B1 that were associated with risk of developing statin-induced myopathy [40]. While this adverse effect would not have been predicted based on genetic studies of the drug target HMGCR (SLCO1B1 does not encode the drug target but instead an organic anion transporter that regulates the hepatic uptake of statins), “post-market” studies of individuals with adverse drug effects have the ability to identify these additional genetic predictors of drug safety.

Future directions

While genetic studies have inherent limitations (in isolation these studies provide no data on changes in the transcriptome or epigenome, for example), dramatic advances in DNA analysis technology now allow for systematic, large-scale efforts to identify individuals who carry inactivating mutations in potential therapeutic target genes and to define the full spectrum of phenotypic consequences of such inactivation. Results from such studies should set the stage for a new era of therapeutics development where medicines are developed that mimic the natural successes of the human genome.

Acknowledgements

NOS is supported, in part, by grants from the NIH/NHLBI (K08HL114642 and R01HL131961) and by The Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital. SK is supported by a Research Scholar Award from the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), the Donovan Family Foundation, R01HL107816, an investigator-initiated research grant from Merck, and a grant from Fondation Leducq.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul SM, Mytelka DS, Dunwiddie CT, Persinger CC, Munos BH, Lindborg SR, et al. How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry's grand challenge. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:203–14. doi: 10.1038/nrd3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullard A. The phenotypic screening pendulum swings. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:807–9. doi: 10.1038/nrd4783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leigh SE, Foster AH, Whittall RA, Hubbart CS, Humphries SE. Update and analysis of the University College London low density lipoprotein receptor familial hypercholesterolemia database. Ann Hum Genet. 2008;72:485–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kathiresan S, Srivastava D. Genetics of human cardiovascular disease. Cell. 2012;148:1242–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Do R, Stitziel NO, Won HH, Jorgensen AB, Duga S, Angelica Merlini P, et al. Exome sequencing identifies rare LDLR and APOA5 alleles conferring risk for myocardial infarction. Nature. 2015;518:102–6. doi: 10.1038/nature13917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein JL, Schrott HG, Hazzard WR, Bierman EL, Motulsky AG. Hyperlipidemia in coronary heart disease. II. Genetic analysis of lipid levels in 176 families and delineation of a new inherited disorder, combined hyperlipidemia. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:1544–68. doi: 10.1172/JCI107332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global Lipids Genetics Consortium. Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, Peloso GM, Gustafsson S, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1274–83. doi: 10.1038/ng.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanseau P, Agarwal P, Barnes MR, Pastinen T, Richards JB, Cardon LR, et al. Use of genome-wide association studies for drug repositioning. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:317–20. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deloukas P, Kanoni S, Willenborg C, Farrall M, Assimes TL, Thompson JR, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new risk loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:25–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahmood SS, Levy D, Vasan RS, Wang TJ. The Framingham Heart Study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: a historical perspective. Lancet. 2014;383:999–1008. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61752-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kannel WB, Dawber TR, Kagan A, Revotskie N, Stokes J., 3rd Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease--six year follow-up experience. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1961;55:33–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-55-1-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, Brumm J, et al. Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2089–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, Chaitman BR, Desvignes-Nickens P, Koprowicz K, et al. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans DM, Davey Smith G. Mendelian Randomization: New Applications in the Coming Age of Hypothesis-Free Causality. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2015;16:327–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-090314-050016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M, Frikke-Schmidt R, Barbalic M, Jensen MK, et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2012;380:572–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, White HD, Steen DP, Lukas MA, Tarka E, et al. Effect of darapladib on major coronary events after an acute coronary syndrome: the SOLID-TIMI 52 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1006–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholls SJ, Kastelein JJ, Schwartz GG, Bash D, Rosenson RS, Cavender MA, et al. Varespladib and cardiovascular events in patients with an acute coronary syndrome: the VISTA-16 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:252–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White HD, Held C, Stewart R, Tarka E, Brown R, Davies RY, et al. Darapladib for preventing ischemic events in stable coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1702–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson A, Gao P, Orfei L, Watson S, Di Angelantonio E, Kaptoge S, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A(2) and risk of coronary disease, stroke, and mortality: collaborative analysis of 32 prospective studies. Lancet. 2010;375:1536–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60319-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmes MV, Simon T, Exeter HJ, Folkersen L, Asselbergs FW, Guardiola M, et al. Secretory phospholipase A(2)-IIA and cardiovascular disease: a mendelian randomization study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1966–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casas JP, Ninio E, Panayiotou A, Palmen J, Cooper JA, Ricketts SL, et al. PLA2G7 genotype, lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 activity, and coronary heart disease risk in 10 494 cases and 15 624 controls of European Ancestry. Circulation. 2010;121:2284–93. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.923383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/

- 24.Plenge RM, Scolnick EM, Altshuler D. Validating therapeutic targets through human genetics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:581–94. doi: 10.1038/nrd4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabes JP, Allard D, Ouguerram K, Devillers M, et al. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat Genet. 2003;34:154–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen J, Pertsemlidis A, Kotowski IK, Graham R, Garcia CK, Hobbs HH. Low LDL cholesterol in individuals of African descent resulting from frequent nonsense mutations in PCSK9. Nat Genet. 2005;37:161–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotowski IK, Pertsemlidis A, Luke A, Cooper RS, Vega GL, Cohen JC, et al. A spectrum of PCSK9 alleles contributes to plasma levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:410–22. doi: 10.1086/500615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Z, Tuakli-Wosornu Y, Lagace TA, Kinch L, Grishin NV, Horton JD, et al. Molecular characterization of loss-of-function mutations in PCSK9 and identification of a compound heterozygote. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:514–23. doi: 10.1086/507488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH, Jr., Hobbs HH. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1264–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3 and risk of ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:32–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crosby J, Peloso GM, Auer PL, Crosslin DR, Stitziel NO, Lange LA, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3, triglycerides, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:22–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Do R, Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, Gao C, Peloso GM, et al. Common variants associated with plasma triglycerides and risk for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1345–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stitziel NO, Won HH, Morrison AC, Peloso GM, Do R, Lange LA, et al. Inactivating mutations in NPC1L1 and protection from coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2072–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kastelein JJ, Akdim F, Stroes ES, Zwinderman AH, Bots ML, Stalenhoef AF, et al. Simvastatin with or without ezetimibe in familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1431–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krumholz HM. Emphasizing the burden of proof: The American College of Cardiology 2008 Expert Panel Comments on the ENHANCE Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:565–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.959577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen JC, Stender S, Hobbs HH. APOC3, Coronary Disease, and Complexities of Mendelian Randomization. Cell Metab. 2014;20:387–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010;375:735–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61965-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frayling TM. Statins and type 2 diabetes: genetic studies on target. Lancet. 2015;385:310–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61639-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Search Collaborative Group. Link E, Parish S, Armitage J, Bowman L, Heath S, et al. SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy--a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:789–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nikpay M, Goel A, Won HH, Hall LM, Willenborg C, Kanoni S, et al. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1121–30. doi: 10.1038/ng.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schunkert H, Konig IR, Kathiresan S, Reilly MP, Assimes TL, Holm H, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:333–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samani NJ, Erdmann J, Hall AS, Hengstenberg C, Mangino M, Mayer B, et al. Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:443–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, Stewart A, Roberts R, Cox DR, et al. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science. 2007;316:1488–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1142447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kathiresan S, Voight BF, Purcell S, Musunuru K, Ardissino D, Mannucci PM, et al. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat Genet. 2009;41:334–41. doi: 10.1038/ng.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466:707–13. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, Demissie S, Musunuru K, Schadt EE, et al. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:56–65. doi: 10.1038/ng.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newton-Cheh C, Johnson T, Gateva V, Tobin MD, Bochud M, Coin L, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight loci associated with blood pressure. Nat Genet. 2009;41:666–76. doi: 10.1038/ng.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association S. Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, Bochud M, Johnson AD, et al. Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature. 2011;478:103–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wain LV, Verwoert GC, O'Reilly PF, Shi G, Johnson T, Johnson AD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies six new loci influencing pulse pressure and mean arterial pressure. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1005–11. doi: 10.1038/ng.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gudbjartsson DF, Arnar DO, Helgadottir A, Gretarsdottir S, Holm H, Sigurdsson A, et al. Variants conferring risk of atrial fibrillation on chromosome 4q25. Nature. 2007;448:353–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benjamin EJ, Rice KM, Arking DE, Pfeufer A, van Noord C, Smith AV, et al. Variants in ZFHX3 are associated with atrial fibrillation in individuals of European ancestry. Nat Genet. 2009;41:879–81. doi: 10.1038/ng.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ellinor PT, Lunetta KL, Glazer NL, Pfeufer A, Alonso A, Chung MK, et al. Common variants in KCNN3 are associated with lone atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2010;42:240–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okada Y, Wu D, Trynka G, Raj T, Terao C, Ikari K, et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature. 2014;506:376–81. doi: 10.1038/nature12873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stahl EA, Raychaudhuri S, Remmers EF, Xie G, Eyre S, Thomson BP, et al. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis identifies seven new rheumatoid arthritis risk loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:508–14. doi: 10.1038/ng.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holmen OL, Zhang H, Fan Y, Hovelson DH, Schmidt EM, Zhou W, et al. Systematic evaluation of coding variation identifies a candidate causal variant in TM6SF2 influencing total cholesterol and myocardial infarction risk. Nat Genet. 2014;46:345–51. doi: 10.1038/ng.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gudbjartsson DF, Helgason H, Gudjonsson SA, Zink F, Oddson A, Gylfason A, et al. Large-scale whole-genome sequencing of the Icelandic population. Nat Genet. 2015;47:435–44. doi: 10.1038/ng.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leipold E, Liebmann L, Korenke GC, Heinrich T, Giesselmann S, Baets J, et al. A de novo gain-of-function mutation in SCN11A causes loss of pain perception. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1399–404. doi: 10.1038/ng.2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Polfus LM, Gibbs RA, Boerwinkle E. Coronary heart disease and genetic variants with low phospholipase A2 activity. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:295–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1409673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elliott P, Chambers JC, Zhang W, Clarke R, Hopewell JC, Peden JF, et al. Genetic Loci associated with C-reactive protein levels and risk of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2009;302:37–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, Snaedal J, Jonsson PV, Bjornsson S, et al. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer's disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 2012;488:96–9. doi: 10.1038/nature11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flannick J, Thorleifsson G, Beer NL, Jacobs SB, Grarup N, Burtt NP, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in SLC30A8 protect against type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2014;46:357–63. doi: 10.1038/ng.2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]