Abstract

Public health efforts focused on Latina youth sexuality are most commonly framed by the syndemic of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, a narrow and often heteronormative focus that perpetuates silences that contribute to health inequities and overlooks the growing need for increased education, awareness, and support for LGBTQ youth. This article presents findings from the project Let’s Talk About Sex: Digital Storytelling for Puerto Rican Latina Youth, which used a culturally centered, narrative-based approach for analyzing participants’ own specifications of sexual values and practices. The strength of digital storytelling lies in its utility as an innovative tool for community-based and culturally situated research, as well as in its capacity to open up new spaces for health communication. Here we present two “coming out” case studies to illustrate the value of digital storytelling in supporting the development of meaningful and culturally relevant health promotion efforts for LGBTQ-identified Puerto Rican Latina youth across the life span.

Introduction

The dominant discourse surrounding the sexuality of Puerto Rican Latina youth commonly excludes the myriad intersections of race, class, ethnicity, gender, and identity, resulting in a silencing about sexuality that is critical to undo in order to meaningfully address persistent inequities in sexual health (Acosta, 2010; Brockenbrough, 2013; Gubrium & Shafer, 2014). Youth sexuality is typically framed “in terms of individual deviance rather than structural impediments” (Peterson, Antony, & Thomas, 2012, p.1), while social, cultural, and structural level dimensions remain un-problematized (Lupton, 1994). Existing health promotion efforts exclusively focus on measureable outcomes such as reduced rates of teen pregnancy and birth, notably by singularly promoting access to and use of Long Acting Reversible Contraceptives (LARCs) and Depo-Provera (Gomez, Fuentes, & Allina, 2014). The accompanying messaging is founded upon research suggesting that delaying pregnancy directly correlates to increases in education, employment, and economic security. However, this is infrequently the case for marginalized individuals. In addition to having strong roots in historically biased systems of population control (Briggs, 2002; Garcia, 2009), these narrowly focused pregnancy-prevention approaches and their accompanying funding structures fail to address and acknowledge the complex social processes and power imbalances that inform sexuality and wellbeing, resulting in the downplaying of critical public health and community-defined issues (Lupton, 1994).

The dominant research paradigm in health communication operates on the basis of a “universality,” or one-size-fits-all, nature of health issues and their solutions (Dutta, 2010). This paradigm is limited because it erases the socially constructed, locally specific, and contested nature of these health issues. Critical health communication theory, on the other hand, “interrogates the values intertwined in the knowledge claims made by biomedicine, as well as the values underlying the social scientific theories that are the primary grounds of claims making for health communication scholars” (Dutta, 2010, p. 535). Thus, critical health communication studies attempt to “foreground the community as an active meaning making participant, engaged in the dynamic and continually negotiated process of meaning making, working amid structures, and simultaneously seeking to disrupt these structures” (Dutta, 2010, p. 537).

This article presents findings from Let’s Talk About Sex: Digital Storytelling for Puerto Rican Latina Youth. In the project, we used digital storytelling (DST) as part of a culture-centered approach (CCA), prioritizing the use of digital and visual narratives as an outlet for young women to analyze their own specifications of sexual values and practices, thus inverting the typical power imbalances inherent to the traditional research process. Through a process built on group solidarity, participants shift from being objectified by their experiences, to transforming their experiences into an object: a digital story (Gubrium, 2009). Here we present two case studies from the project to illustrate the value of this narrative process for signaling gaps in current sexual health intervention design, and to inform the development of meaningful health promotion efforts for LGBTQ Puerto Rican Latina youth.

Background

The bulk of health communication research on youth sexual health and sexual health inequities commonly centers on interfamilial/interpersonal patterns of communication, barriers to care-seeking, assessments of knowledge and attitudes, and the effects of media on sexual health behaviors and attitudes (Askelson, Cambo & Smith, 2011; Pinkleton, Austin, Cohen, Chen & Fitzgerald, 2008; Williams, Pichon & Campbell, 2015). While these efforts have positively impacted outcomes of interest such as teen pregnancy rates, care-seeking behaviors, communication about sexuality, and use of contraceptives, in the context of sexual health inequities we find the exclusion of community voice and a discussion of the structural factors that silence marginalized individuals a considerable limitation. The growing body of literature about the culture-centered approach in the context of sexual health utilizes textual narratives to inform findings (Acharya & Dutta, 2011; Dutta & Acharya, 2014; Sastry, 2015); we are unaware of other research that uses digital storytelling as a culture-centered approach in the context of youth sexuality.

Sexual health and Latina youth

The current approach to addressing sexual health inequities experienced by Puerto Rican Latina youth is foundationally limited by assuming both homogeneity and heteronormativity (Acosta, 2010; Brockenbrough, 2013; Garcia, 2009; Gubrium & Shafer, 2014). Lumping Latinas into one group ignores the vast and varied culturally and contextually relevant histories that impact health and health outcomes, ignoring that “issues related to sexuality are not simply maintained within bodies; they are shaped by and serve a wider social and political terrain” (Asencio & Battle, 2010, p. 2). However, there is limited research that focuses specifically on sexuality among Puerto Rican Latinas. Thus, we proceed carefully by drawing from research among “Latinas,” acknowledging the tensions in doing so.

Among Latino/a families, silences around sexuality inform how sexual identities are discussed and negotiated. Sexuality is commonly a taboo topic that remains unaddressed until an event, such as pregnancy, rape, or “coming out” occurs (Acosta, 2010; Brockenbrough, 2013). The dichotomy of “good girl/bad girl” is a reoccurring theme, reinforcing notions of heteronormativity, traditional gender expectations, and perpetuating existing silences (Acosta, 2010; Garcia, 2009). Parental approval of “good girls” who are not “boy crazy” turns a blind eye to developing romantic relationships between LGBTQ Latina youth, increasing pressures to maintain multiple identities (Acosta, 2010). As LGBTQ youth reach expected marrying and childbearing age, familial approval shifts to disapproval when this is not actualized, further emphasizing pressures to conform to heteronormative expectations and maintain silences (Asencio & Battle, 2010; Brockenbrough, 2013). The intersection of culture, migration, and economic inequities reinforce the strength of and dependence on family, who provide essential support in the face of a multiplicity of structural and social barriers. Thus, the internal negotiation of coming out is constantly balanced against potential loss of connection and support. The closer the ties to family, the less likely LGBTQ youth are to disclose their sexuality (Acosta, 2010; Asencio & Battle, 2010; Garcia, 2009). Coming out and risking rejection can further exacerbate the daily vulnerabilities faced by LGBTQ youth of color; over the life course they are at increased risk for mental health challenges, substance abuse, teen pregnancy and STIs (Garcia, 2009; Lindley & Walsemann, 2015).

Further compounding these silences surrounding sexuality are the limitations of current sexual health programming. Although federal funding for sexual health programming reflects a shift in priorities away from an abstinence-only focus, the bulk of funding is channeled to heteronormatively defined and articulated Teen Pregnancy Prevention Initiatives and HIV/AIDs and STI prevention efforts that primarily exclude LGBTQ youth, despite the fact that LGBTQ youth have higher rates of unprotected heterosexual sex and pregnancy than their heterosexual counterparts (Lindley & Walsemann, 2015, emphasis added). In our study site, sexual health education is not mandated, and decisions about curricular content are left to the discretion of local school boards who struggle with balancing limited resources (Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States, 2013).

Our study site (which we will refer to as “the City”) is home to one of the largest Puerto Rican populations in the United States, and contemplating this complex colonial history provides a critical understanding of the unequal social relations and power dynamics that perpetuate the income and health disparities that impact daily lived experience (Leatherman, 2011). With the 1917 Jones Act, Puerto Ricans became U.S. citizens, after the U.S. assumed control over Puerto Rico in 1898. In the Post World War II era, “Operation Bootstrap” was instituted and funded by the U.S. government to support economic development in Puerto Rico, primarily through the establishment of urban factories that cemented the transition from an agrarian to a manufacturing economy. This shift in economy promoted an internal migration within Puerto Rico from rural to urban areas, resulting in high rates of unemployment, poverty, overcrowding, and poor health. In response, U.S policies promoted both migration and sterilization in response to what was coined a “population problem” at the time (Black, 2009). Between 1937 and 1968, sterilization was the only consistently available form of fertility control for Puerto Rican women living on the island. By 1974, 200,000 women (35% of the female population) had undergone sterilization; the average age was 26 (Briggs, 2002).

In response to the economic recession on the island, the U.S. Department of Labor helped to establish an agreement between U.S. companies and the Department of Labor in Puerto Rico to send Puerto Rican farmers to the City to work on tobacco farms. However, when Puerto Ricans first arrived in the City in the 1960s, it was already in the throes of post industrialization as a former paper mill boomtown (Briggs, 2002). As the last migrant group arriving in the City, they were the first to become unemployed. Today, many Puerto Ricans in the City continue to live in substandard housing, have little access to good jobs and/or work in very low-wage jobs, and are rampantly racialized. Structural violence persists (Black, 2009).

Digital Storytelling

Process of digital storytelling

Digital stories are short (1–3 minute), first person visual narratives that synthesize digital imagery, audio recordings, music, and text to document personal experiences. For a complex topic such as youth sexuality, DST “supports our stance to privilege research as a process that positions traditionally silenced and objectified participants as active and legitimate knowers of themselves and their circumstances” (Peterson, Antony, & Thomas, 2012, p. 3). The DST process has the potential for marginalized individuals to identify and strengthen social support systems by listening to others and being heard (Alexandra, forthcoming). Common themes in the workshops included those related to structural, social, and interpersonal levels of violence (Gubrium, Fiddian-Green, & Hill, forthcoming).

The workshop format utilized by the StoryCenter is previously detailed in the literature (Gubrium, Fiddian-Green, & Hill, forthcoming; Gubrium & DiFulvio, 2011). DST is a process-based methodology with three elements: the group process, the individual process, and the researcher/facilitator/participant process. The group process consists of the story circle and the story screening. On the first day of the workshop participants’ share the story they are contemplating writing in a group setting (i.e. the story circle), receiving structured feedback from group members and facilitators. The story screening occurs on the last day of the workshop. Each participant introduces and shows their final digital story, with facilitators leading a group discussion around the content of individual stories, and the body of stories. The individual element of the process involves writing the story, collecting images to visually narrate the story, and learning the basics of video editing software to produce the final digital story. Accomplishing these steps can contribute to a participant’s sense of self-worth and value. Lastly, the researcher/facilitator/participant process involves the co-construction of knowledge as researchers and facilitators support participants with script editing and the collection of images, yielding an iterative process of storytelling (Gubrium, Krause, & Jernigan, 2014).

A culture-centered approach to health communication

Predominant approaches to health communication with marginalized, multi-cultural populations commonly utilize a culturally sensitive approach. This tactic remains linked to traditional persuasive messaging campaigns, despite adapting and tailoring messages to be culturally relevant. While culturally sensitive approaches to health communication importantly acknowledge the variation that exists across and between cultures, they remain limited by the very nature that the “cultural characteristics that are considered relevant by the health communicator” (Dutta, 2007, p. 306) are the ones ultimately chosen for persuasive effect by outside public health experts. Culturally sensitive approaches can therefore reinforce negative and stereotypical messaging about particular cultures by excluding, and thus silencing, structural factors that inform health and wellbeing.

The Let’s Talk About Sex project emerged as an alternative to behavioral and persuasive approaches to addressing sexual health inequities and in response to the question: what can improve current programming efforts focused on sexual health for Puerto Rican Latina youth? Our strategy was to utilize a culture-centered approach (CCA) as a framework that calls for the “voice of the community [to be] central to the articulation of health problems and corresponding solutions” (Dutta, 2007, p. 307). In so doing, “cultural contexts are placed at the core of meaning-making processes, and meanings are dialogically co-constructed by researchers and cultural participants” (Basu & Dutta, 2009, p.86), creating the potential for participants and researchers to reflect on issues and take action collectively (Peterson, Antony & Thomas, 2012). The shift away from techniques of persuasion toward the creation of “health-enabling social change” is more likely to yield sustainable and meaningful changes in health (Campbell & Cornish, 2011). We used digital storytelling (DST) as a CCA to encourage dialogue among young Puerto Rican women living in a marginalized community to voice their own stories that coexist about sexuality, health, and wellbeing; to bolster solidarity in the group; and to consider ways of moving forward for action.

Central to the culture-centered approach is the “emphasis on interrogating the erasures in health communication discourse and application” (Dutta, 2008, p.4) via three tenets: (1) a focus on local cultural contexts informing meanings and experiences of health, (2) prioritizing agency, which is predicated on a dialogic/process-oriented approach that engages participant voices and acknowledges the co-construction of knowledge, and (3) an acknowledgement of structural dimensions, which both constrain and facilitate agency, and, through a deep analysis of social inequality, politicize the endeavor of public health research (Dutta, 2008). In analyzing the interactions between these three constructs, culture-centered theorists examine how power is positioned to promote continued marginalization of cultures, and advocate for the use of participatory narrative approaches to create the space for unexpected, yet important stories and experiences to emerge (Dutta, 2008).

Taking a culture-centered approach, the Let’s Talk About Sex project emerged from our long-term work in the community, and in collaboration with local organizations whose priority is to both increase access to sexual health services and reduce the high teen pregnancy and birth rates in the region. Although the original focus of this project developed from a community-based agenda to gain a deeper understanding of sexuality in reference to high rates of teen pregnancy and birth among Puerto Rican Latina youth, the DST process elicited the need for increased support and empowerment around sexual health for LGB-identified Puerto Rican Latinas. This is an area that has been under-prioritized and overshadowed in the local area by predominating efforts solely focused on reducing rates of teen pregnancy. In this article we present two “coming out” stories from our DST workshops to illustrate salient findings from the process.

Methods

Study Site and Sampling Procedures

The project was based in the City, a post-industrial, former mill town that ranks among the five most challenged in the state on numerous sexual and reproductive health indicators, including having the highest teen birth rate (age 15–19) among all cities in the state with populations of greater than 40,000, and an adolescent (<15) birth rate four times greater than the state rate (State Community Health Information Profile [StateCHIP], 2013). Structural antecedents underlie these disparities. City residents face tremendous disadvantage: 46.3% of the population lives below 200% poverty, and 51% of households are single parent homes living below 100% poverty. The official unemployment rate is over 31%; and the annual per capita income for Latina/os in the City is $7,757. Inequity is further accentuated for City youth: 42% of youth under the age of 18 grow up in poverty (StateCHIP, 2013).

Our project consisted of three, 4-day DST workshops; each enrolled ten Puerto Rican Latinas aged 15–21. For each workshop, we enrolled 10 participants who were recruited by staff at partnering agencies that serve community youth, as well as through direct contact by research assistants (including the first author) who visited the agencies. In keeping with the CCA, our community partnerships were critical to the identification of youth who would benefit from participation. Additionally, and particularly given that we were working with youth, we viewed our connections to these agencies as critical to remaining connected to participants during and after the workshops, and well as working with them in order to achieve our long-term program of research: developing a culture-centered narrative health promotion process that works with community members to devise appropriate action.

Recruitment criteria included: 1) self-identification as a Puerto Rican Latina; 2) living or receiving services in the City; 3) aged 15–21; and 4) pregnant/parenting or not pregnant or parenting, depending on the workshop. Parental consent and participant assent was obtained for all participants under the age of 18; all participants over the age of 18 signed a consent form. Our university’s Institutional Review Board approved the project protocol. Workshops were held at a local partner agency that works to increase access to sexual health programming for youth, and were facilitated by the StoryCenter and a local media partner. Thirty total participants were enrolled; 29 completed a digital story. 1

Multimodal Data Collection

In the Let’s Talk About Sex project we used an ethnographic approach to document the local “complex web of meanings” surrounding sexuality, which are “intertwined with the shared values, beliefs and practices that run through the strands of a community” (Geertz, 1985, p.11). A team of four researchers observed and assisted with each workshop, using a field observation form to capture aspects of the process that were not audio recorded (only the story circle and story screening were recorded). Two researchers conducted semi-structured follow-up interviews with each participant and wrote additional field notes around the interviews. Data gathered included: 1,200 pages of transcripts from the story circle, story drafts, final digital stories, story screening, and follow-up interviews; 450 pages of field notes from each workshop and follow up interview; intertextual analyses (Figures 1–3) of 29 digital stories; and participant responses to workshop evaluations and pre-, post-, and follow-up surveys about impacts on sexual attitudes, beliefs, and practices, social support and empowerment.

Figure 1.

Intertextual Analysis

Figure 3.

Intertextual Analysis

Data Analysis

A specific aim of the project was to use constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2010) to examine and delineate salient cultural paradigms of sexuality embedded in the data. Restricting our analysis of visual imagery strictly to words depicted a flatness that is incongruent with our prioritization of multimodal methodologies and holistic understandings of health. To render the digital stories in a “rounder” fashion, we used an intertextual transcription method (Figures 1–3). This transcript style allows a verisimilitude of the visual, chronological, aural and oral, emotional, gestural, and textual components found in the digital story (Gubrium, Krause, & Jernigan, 2014), contributing critical detail to our analysis.

To systematically organize and code the data we used MAXQDA (11.2.0). Our step-by-step data coding scheme proceeded as follows: 1) Three research team members independently reviewed the corpus of data, including the digital stories in intertextual transcript and video narrative form; 2) each researcher inductively composed a list of categories derived from participants’ natural language statements that reflected emerging patterns and themes; 3) from this list, each researcher developed a descriptive topical coding matrix in the form of “free nodes”; and 4) we shared our independent coding schemes and reached consensus on the emergence of a second level “tree node” structure from analysis of first level data. Of particular interest to us were shared values, beliefs, and practices (“cultural paradigms”) found within the free nodes. Lastly, 5) collectively, and over multiple iterations, we reviewed the data using the tree node structure to guide further analysis and interpretation. To optimize validity and reliability we sought to minimize discrepancies between participants’ views and the researchers’ interpretations and seek theme saturation (Charmaz, 2010; Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

In our analytical strategy we examined narrative content, context and discourse (Morse & Field, 1995). Content analysis focused on local cultural paradigms of sexuality found in the data. Contextual analysis focused on perceptions and structural circumstances (i.e., historical, political, economic) of sexual identities and practices. Discourse analysis focused on specific ways of articulating sexuality, including the range of values, beliefs, cultural norms, and themes of dissonance. Specifically, we analyzed the ways in which participants’ stories and storytelling activity reveal a) Who they think they are when they are telling the story (enacted cultural identities), b) Who they think they are telling the story to (audience), c) What connections they intuitively make between concepts like “health” and “sexuality,” d) What sexual practices they see as acceptable, natural, appropriate, and so on (cultural norms), and e) What systems of knowledge they privilege when making sense of their health and sexuality (values and beliefs) (Morse & Field, 1995).

Case Study Methodology

Although findings from case studies may be limited in their generalizability, they provoke new and important questions. Taken as individual case studies, digital stories and accompanying interviews and field notes can elicit a depth often lacking in traditional, non-participatory methods (Flyvbjerg, 2006). In this instance, atypical cases such as the “coming out” case studies presented here, become critical to the discovery of previously silenced voices on sexuality and health in the community, and to the development and testing of new hypotheses (Flyvbjerg, 2006). What is crucial to highlight is that these silences not only pertain to the intersections of race, ethnicity, identity, history, and housing and economic insecurity, but also that the right questions are not necessarily being considered and asked when research agendas and goals are developed. Two case studies from separate workshops with intertwined, revelatory themes provide compelling data, strengthening our overall findings (Yin, 2013). As opposed to presenting our findings thematically, we do so instead by case to illustrate our methodological approach, which included analyzing each case individually, then comparing themes between both cases. Our first case was revelatory, highlighting a theme that our team did not anticipate given the project focus. The emergence of a second case with similar thematic content reinforced these unexpected findings as critically important to assess in more depth (Yin, 2013). This allowed us to begin developing a framework for being sensitive to future cases in the course of our ongoing work that may have otherwise escaped our attention.

Results

We turn now to the presentation and discussion of two case studies from the Let’s Talk About Sex project, focusing on Dalia and Monica’s stories about “coming out.” Two themes shape the cases: (1) silencing of alternative sexual identities due to perceived or actual rejection/displacement as a result of “coming out,” and (2) related and targeted bullying in the school setting. Our findings highlight the need to consider both the short- and long-term health implications for LGBTQ Puerto Rican Latina youth, who may lack support for coming out to communicate and actualize diverse sexual identities. Although Dalia and Monica were the only two workshop participants to openly identify as lesbian, four additional participants indicated on their demographic survey that they identified as bisexual. Thus, the percentage of workshop participants that identified as lesbian or bisexual (21%) was considerably higher than the estimated percentage for females in the general population – 1.5% and 0.9% respectively (U.S Department of Health and Human Services, 2014).

Case Studies

“I hadn’t planned to tell”: Dalia’s story

Dalia2 produced her digital story in our first workshop. On the first day, she was a remarkably outspoken and active participant. However, as the workshop progressed she became more quiet and withdrawn, removing herself from the group at large. Up until the last moment, she refused to share her completed digital story, despite sharing her story with the group during the story circle on day one of the workshop. An excerpt from Dalia’s story script backgrounds this hesitation:

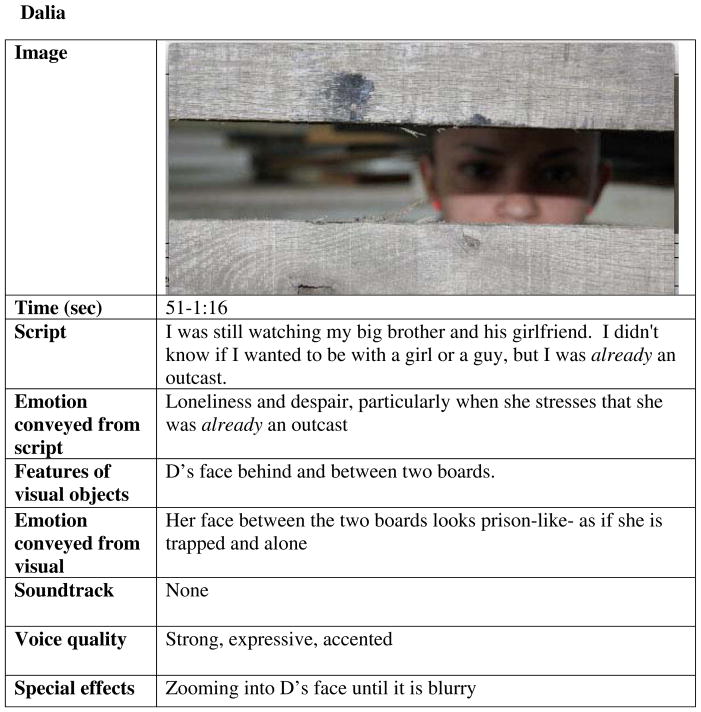

I remember the first time, I couldn’t tell anyone. She was my brother’s age – she was really pretty…I liked to stare at her. Once, I kissed her close to her mouth, then ran and hid under the bed. I was taken away from my mom soon after that, and lived with my aunt who was a strict church lady. That was a hard time for me in so many ways. I locked myself in my room and didn’t really talk to anyone. I couldn’t figure things out… I was still watching my big brother and his girlfriend. I didn’t know if I wanted to be with a girl or a guy, but I was already an outcast.

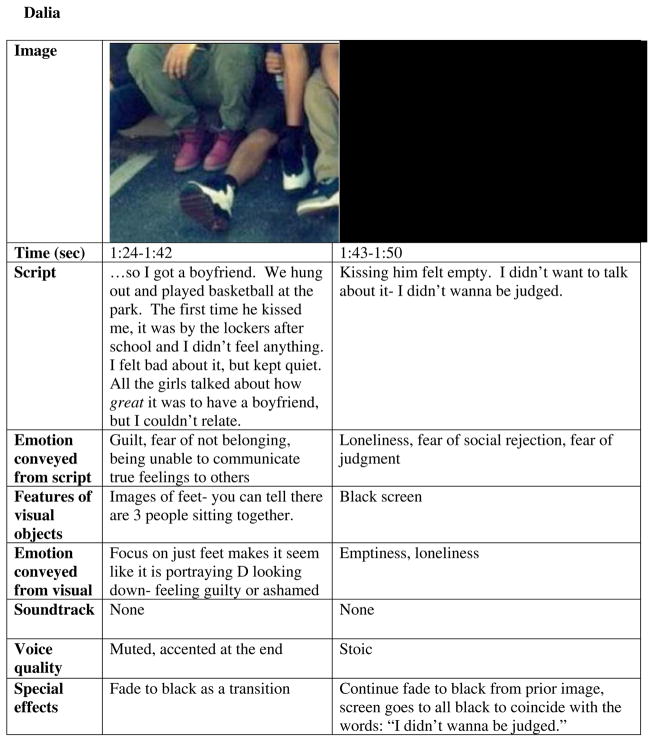

In Dalia’s story, fear of rejection, as she terms it – of being an “outcast” – significantly informs her sexual practice. Both her tone of voice and use of imagery convey a sense of despair and loneliness. In order to depict the sense of imprisonment from the silences that she must maintain in order to “fit in” and not “be an outcast,” Dalia chooses an image in which her face is framed between two boards (Figure 1). Later in her story, Dalia recounts “getting a boyfriend” to safeguard herself and maintain her silence about her sexuality for fear of potential social repercussions, namely isolation—a tangible fear. Her voice bears the weight of carrying her silence, as she recalls what it was like to kiss her boyfriend for the first time: “I didn’t feel anything. I felt bad about it, but kept quiet. All the girls talked about how great it was to have a boyfriend, but I couldn’t relate. Kissing him felt empty. I didn’t want to talk about it – I didn’t wanna be judged.” At this point in her digital story, the screen is completely dark; Dalia’s choice of imagery transports the viewer, explicitly expressing the internal struggle that she experiences in this moment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Intertextual Analysis

In contrast, when Dalia meets a girl who she describes as being “like her diary,” the listener can hear her smiling as she speaks. However, she still feels the need to maintain the silence about her sexuality. When she does come out spontaneously and accidentally to her aunt, with whom she has lived for six years, Dalia says that she “hadn’t planned to tell. The look on her face made me wish I hadn’t. I started locking myself in my room again, not talking. I got sent to foster care because my aunt wasn’t comfortable with me.”

When asked in a follow-up interview about what support systems are beneficial to youth and families, without hesitation Dalia identified “family therapy” for its value in improving “communication.” For her, family support is essential—it “feels good to have your own family, your own blood – support you.” Yet, surrounding her coming out story is the burden of silence. Dalia has little support: she noted in her interview that her family’s opinion was that “what I was doing was wrong.” At the end of her interview, Dalia reveals that her sister/cousin recently came out to her as being bisexual, but “wouldn’t come out to my aunt because of what I went through. I’m pretty sure she’s scared.”

Dalia also highlighted the sexual silencing that is predominant in the school system in her follow-up interview. The heteronormative slant of the sexual health education offered to students focuses narrowly on potential interactions between boys and girls, especially related to developing negotiation skills around the use of contraception to prevent pregnancy. Dalia identified wanting to know more, yet feeling unable to ask for and access necessary information. Dalia also spoke of her experience being bullied in school because of her sexual and gender identity. In one instance a student confronted her in the hallway, telling her that if she wanted to “dress like a boy, she should take a hit like a boy,” and proceeded to “knock her out to the ground.” Dalia and the student were both removed from school by police officers after the altercation. Both were suspended for five days, with little repercussion for the aggressor, despite the targeted physical attack on Dalia. Monica’s story, produced during the second workshop, echoes the salient themes presented in Dalia’s story: those of sexual silencing and being bullied.

“I hope you end up with a boy”: Monica’s story

Monica was viscerally quiet and shy during group work throughout the workshop. During a debrief meeting with facilitators and researchers at the end of first day of the workshop, the lead facilitator mentioned that Monica had two possible stories she would like to tell: one about her experience of being bullied in school, and the other about coming out as gay. Ultimately Monica decides that her bullying story was too emotional to share, and would exacerbate her feelings of vulnerability. Her final story, with an excerpt presented below, focuses on “coming out”:

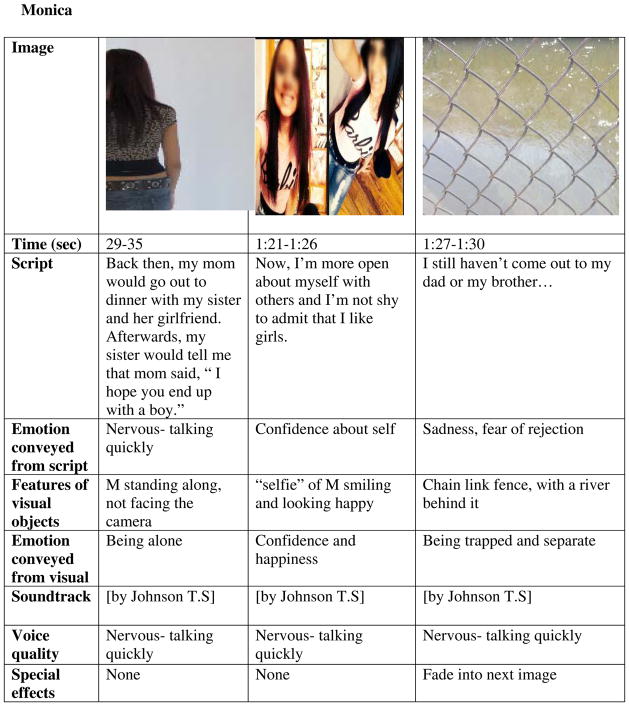

It started off by me having crushes on Rhianna and Nicole. Looking back, I realize it was the same feelings my friends had for Justin Bieber and Chris Brown. When I turned 13, my older sister came out to me. This helped me, because as I was becoming a teenager my feelings were not only for celebrities, but also for girls at my school. Sitting in class, I would find myself attracted to other girls. Back then, my mom would go out to dinner with my sister and her girlfriend. Afterwards, my sister would tell me that mom said, “I hope you end up with a boy.” I felt scared that she would say the same thing to me.

Unlike Dalia, who exudes a deep maturity from her varied and difficult life experiences, including “staying on the streets” with her brother at age six, Monica’s innocence (despite being two years older than Dalia) is conveyed through her use of music (lite pop music that often overshadows her voice) and imagery (primarily flowers and “selfies”). However, the underlying themes of silencing and fear of rejection predominate.

Monica’s story centers on her self-imposed sexual silencing. Like Dalia, she also tells about dating boys in an effort to “fit in.” Monica also describes maintaining gendered silences about her sexuality within her family. Monica noted in her individual interview that she had come out to her mother and sister, but still felt unable to do so with the men in her family. A sense of uncertainty and fear informed her decision to not come out to her father and brother as she described in her interview: “my father is really against it [being gay], so I’m really scared to tell him.” Striking were her fears of dislocation from home – Monica identified her fear of being placed in a foster home as a consequence of coming out to her father. She elaborated on examples of young people being “kicked out” of their homes or “disowned” after coming out to their parents as the main deterrent to telling her father.

Like Dalia, Monica also spoke of feeling judged in relation to her sexual identity, explaining that she doesn’t “fit in.” A victim of bullying from elementary school through high school, Monica talked about being kicked, hit, and repeatedly teased by classmates from an early age. Although her parents advocated on her behalf, eventually switching her to another school, there were also no repercussions for the individuals bullying her.

During her interview, Monica described the sexual silencing present in the health education she received in school and in the information she received from her pediatrician. As with Dalia, she identified a strict heteronormativity around gender norms and expectations about young men, young women, and sexuality that are geared toward pregnancy prevention, with risk narrowly linked to proscribed interactions between girls and boys. Not explored is the potential for heterosexual relationships to serve as a testing ground for alternative sexualities, much less the vulnerabilities evoked through these interactions. Describing interactions with healthcare providers in her interview, Monica spoke of the assumptions about her sexuality based on her feminine appearance: “They don’t know at first that I’m gay…They just ask if I am sexually active, but they don’t know that I’m…they think as like, have I ever had sex with a guy.”

Together with bullying, the need for support in coming out to actively articulate her sexual identity was a prominent theme. During her interview, Monica reported that families should be “open with their kid” and “not [be] judgmental.” In addition to having limited support from her family around her sexuality, Monica noted that all of her friends were straight, stating: “I kinda wish I had friends that are gay or bi, but I haven’t met anyone like that.” Instead, her social support system of gay youth is limited to social media: followers on Instagram, a few Facebook “friends” that she had “crushes” on, and a YouTube video series that she watched about a young lesbian couple. These connections make her “feel like [she’s] not the only one who feels that… [W]hen I see other people on the Internet, they understand…” she said. Of note here is her use of the euphemism “that” in place of articulating her sexual identity. Distancing herself from her sexuality was a common theme throughout her interview, despite claims made in her story that she was “more open about myself with others.”

To present Monica’s digital story, we have placed three un-sequenced (though chronological) intertextual transcript columns together to present multi-sensory elements that convey critical elements in the story (Figure 3). The first column contains an image that shows Monica looking away from the camera. Juxtaposed with the image, her voiceover narration describes her experience with self-identifying as gay. The second column depicts an image of Monica happily taking a smiling “selfie,” alongside a voiceover narration in a tone that exudes confidence about her sexual orientation as she states: “I’m not shy to admit that I like girls.” The image in the third column shows a chain link fence. In the accompanying voiceover Monica states that she has yet “to come out to my dad or my brother.” Analyzing the images together conveys the psychosocial turmoil inherent to the navigation and performance of sexual identity to oneself and family.

Discussion

As part of a culture-centered approach, the digital storytelling method engages and equips marginalized communities with the resources to document their silenced experiences of health, and to identify solutions that integrate entire communities (Dutta, 2007). This signifies a shift in the research landscape away from simply the search for knowledge, towards empowering “community members towards social change praxis” (Gubrium & DiFulvio, 2011, p.41). The sharing of stories within a DST workshop generates emergent commonalities of health inequities that are so often framed by structural and social violence (Gubrium, Fiddian-Green, & Hill, forthcoming). Further, the group process fruitfully produces a sense of solidarity among participants (Gubrium & DiFulvio, 2011). For the Let’s Talk About Sex project, we see the creation of space for alternative and subaltern voices that both interrogate and disrupt the dominant and heteronormative discourse on youth sexuality as an act of social change that is in keeping with the core tenets of the culture-centered approach. Though this disruption and re-voicing is an act of “resistance” in itself, CCA projects may go further by promoting social action and social change, for instance through the formation of advisory boards and grassroots organizations.

We know that the current heteronormative approach to sexual health programming and education primarily focuses on teen pregnancy prevention and access to birth control, overlooking significant needs of LGBTQ youth. In seeking to identify cultural paradigms of sexual health among Puerto Rican Latina youth in the City, the DST process allowed us to identify the particulars of those gaps in knowledge and services. Our findings highlight multiple contingencies that shape how Puerto Rican Latina youth negotiate the disclosure of alternative sexual identities, both at the social (with peers and family) and institutional (bullying and the limited nature of sexual health education in the school and public health setting) levels.

The 29 digital stories produced in the Let’s Talk About Sex project point to the multiple ways in which a dominant discourse around teen pregnancy that is almost singularly prevention focused perpetuates narratives that further disenfranchise Puerto Rican Latinas. For Monica and Dalia in particular, their stories viscerally illustrate their experiences of identifying as lesbian. For both storytellers, “coming out” to express their sexual identities was shrouded by fear: fear of losing familial and social connections, fear of physical harm and lack of protection, fear of being ejected from their homes, fear of being homeless or placed in foster care, fear of being alone and overlooked. These fears directly impacted their daily, lived experiences, and their literal (not perceived) abilities to safely voice their sexual identities within multiple structures: home, family, school, and the health care and social service systems. Dalia and Monica’s digital stories were crucial narratives that became expressions of “agency as their stories illustrate how they make sense of their structural conditions and how they go about their daily lives with and in spite of these conditions” (Daniel, 2015, p. 99). Creating the space for the identification of structural barriers to positive sexual health has the potential to disrupt the prevailing discourse that places the responsibility for positive sexual health in the hands of youth themselves, by shifting the focus towards policymakers and local systems of government that hold the power to directly impact those structures (Daniel, 2015).

Our prioritization of a participatory, visual method such as digital storytelling enhances current approaches to the CCA, which primarily rely on the use of textual narrative processes. As digital artifacts, the format of digital stories makes them readily accessible to communities in ways that textual narratives are not; they are the “outcomes of multisensory contexts, encounters, and engagements” (Pink, 2011, p. 602), and as such, can be interpreted and experienced on multiple levels by researchers, community members, and the storytellers themselves. Digital stories are unique in that they serve as valuable artifacts, both as rich narrative case studies, and as storied data points used to affect change. As outcomes of a process that is social, digital stories can become catalysts for collective, social action (Mitchell & de Lange, 2011). As a body of data, digital stories can be shown in varied group settings (e.g., the workshop space, community forums, academic conferences, and with health and social service providers), as tools of engagement to facilitate discussion and action to disrupt the dominant discourse around community-prioritized areas of interest.

In addition to supporting the articulation of cultural contexts of sexuality and health, as well as the identification to structures that perpetuate inequities, we view digital storytelling as an agentive process that activates participants through a set of learned technical skills distinct to digital storytelling, which can then be applied in other contexts. Participants, most of whom had limited proficiency with word processing and video editing skills, left the workshop with increased confidence in their ability to do both.

Key Implications and Future Steps

Two key implications arise from our case study findings. First is the limitation of current heteronormatively-prescribed sexual health programming and services that exclude LGBTQ youth. Evidence-based or otherwise, narrowly defined curricula put young people at a greater risk for adverse health outcomes (Garcia, 2009; Gubrium & Shafer, 2014). Furthermore, the “failure to consider the intersections of race and sexuality in the lives of queer youth of color produces dangerous gaps in the bodies of knowledge” that currently inform educational policies (Brockenbrough, 2003, p.432). Shifting sexual education polices through collaborative means to meet the needs and desires of young people is a critical next step for the City.

A second key implication is the need for improved social support and outreach for questioning and out LGBTQ Puerto Rican Latina youth and their families. Perhaps ironically, Dalia’s experience in the foster care system exposed her to social support services that she cited as essential to her self-esteem and survival as a lesbian-identified youth. In contrast, Monica’s lack of real-life social support and dialogue around her sexual identity, as well as her struggle to come out to her entire family, highlights a significant gap in available services and outreach efforts. Although Monica found support through various social networking sites, this is not comparable to the tangible support Dalia received in real-life dialogue during interactions with her therapist, foster parents, and assorted social service providers. Increasing and strengthening programming that offers on-the-ground social support and outreach for LGBTQ youth and their families, to reduce the stigma associated with the identification of alternative sexualities, is a crucial policy priority for the City.

In our present study, we believe we have achieved the first two goals of a CCA project—by challenging the dominant ways we organize and apply knowledge about youth sexuality in a marginalized population, and by opening a space for alternative meanings and experiences to emerge. To continue moving forward as a CCA project, future steps include securing additional funding to support the development of a communication strategy to further engage community members and policy makers towards social action and change.

Conclusion

In the Let’s Talk About Sex project, we prioritized visual, participatory research methods to elicit and surface the silences and spaces of vulnerability that ultimately shape the articulation of sexual identity among Puerto Rican Latina youth in the City. Truth and experience (i.e. the evidence) are contextual and dynamic, yet traditional public health approaches tend to isolate experience, identify problems, and create narrow and instrumental solutions to addressing those “problems” in a way that does not adequately address inequities in health and wellness. Through an approach like DST, we seek to prioritize methodologies that activate—not suppress—the co-creation of knowledge (Gubrium & DiFulvio, 2011). The strength of DST lies in its utility as an ethnographic tool for conducting community-based and culturally situated research, as well as in its capacity to open up new spaces for health communication.

Our findings suggest that the ways in which sexuality is communicated on and around Puerto Rican Latina youth is heteronormatively circumscribed, and as such, limited and ultimately harmful to questioning and out LGBTQ Puerto Rican Latina youth. We propose that the discourse around youth sexuality should be reimagined to integrate the needs of LGBTQ youth. Specifically, we call for: (1) more responsive policies around bullying that address sexual and gender harassment and question static cultural or institutional norms; (2) expanding sexual health education to be inclusive of a myriad of sexual identities; and (3) social support programs that can improve communication around “coming out” with peer and family networks, and within the educational and healthcare settings.

Uncovering previously silenced stories is the first step towards a culturally centered social change agenda. Digital stories can stimulate new conversations through community driven discussion, and encourage a reconceptualization of sexuality education programming, which may lay the foundation for a culture-centered process for social change within the City. The final stories chosen by these two storytellers do not represent the dominant narrative about sexual health among Puerto Rican Latinas in the City. Yet, it is these stories that are essential to be heard, as they stimulate dialogue and broaden the scope of, and approach to, public health promotion efforts. The voicing of these previously untold stories has vast potential for personal empowerment among storytellers, and can serve as the impetus of change and a re-visioning of Puerto Rican youth sexuality.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21HD075081. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Footnotes

Details on the larger study can be found in two other publications (Gubrium & Peterson, forthcoming; Gubrium, Fiddian-Green, & Hill, forthcoming).

Pseudonyms are used for all participants.

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandf.com/hhth

Contributor Information

Alice Fiddian-Green, School of Public Health and Health Sciences, Department of Health Promotion and Policy, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Aline C. Gubrium, School of Public Health and Health Sciences, Department of Health Promotion and Policy, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Jeffery C. Peterson, Murrow College of Communication, Washington State University.

References

- Acharya L, Dutta M. Deconstructing the portrayals of HIV/AIDS among campaign planners targeting tribal populations in Koraput, India: A culture-centered approach. Health Communication. 2011;27:629–640. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.622738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta K. How could you do this to me? How LGBTQ Latinas negotiate sexual identity with their families. Black Women, Gender, and Families. 2010;4:63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandra D. Are we listening yet? Participatory knowledge production through media practice: Encounters of political listening. In: Gubrium A, Harper K, Otanez M, editors. Participatory visual and digital research in action. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Asencio M, Battle J. Introduction: Special issue on Black and Latina sexuality and identities. Black Women, Gender and Families. 2010;4:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Askelson M, Cambo S, Smith S. Mother-daughter communication about sex: The influence of authoritative parenting style. Health Communication. 2011;27:439–448. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.606526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, Dutta M. Sex workers and HIV/AIDS: Analyzing participatory culture-centered health communication strategies. Human Communication Research. 2009;35:86–114. [Google Scholar]

- Black T. When the heart turns rock solid: The lives of three Puerto Rican brothers on and off the streets. New York, NY: Pantheon Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs L. Reproducing empire: Race, sex, science, and US imperialism in Puerto Rico. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brockenbrough E. Introduction to the special issue: Queers of color and anti-oppressive knowledge production. Curriculum Inquiry. 2013;43:426–440. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Cornish F. How can community health programmes build enabling environments for transformative communication? Experiences from India and South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;16:847–857. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9966-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel T. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. National University of Singapore; Singapore: 2015. Meanings of sexual health among gay men in Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta M. Communicating about culture and health: Theorizing culture-centered and culture-sensitivity approaches. Communication Theory. 2007;17:304–328. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta M. Communicating health. Malden, MA: Polity Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta M. The critical cultural turn in health communication: Reflexivity, solidarity, and praxis. Health Communication. 2010;25:534–539. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.497995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta M, Acharya L. Power, control and the margins in an HIV/AIDS intervention: A culture-centered interrogation of the “Avahan” campaign targeting Indian truckers. Communication, Culture, & Critique. 2014;8:254–272. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry. 2006;12:219–245. doi: 10.1177/1077800405284363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia L. “Now why do you want to know about that?”: Heteronormativity, sexism, and racism in the sexual (mis)education of Latina youth. Gender and Society. 2009;23:520–541. doi: 10.1177/0891243209339498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. Local knowledge: Further essays in interpretive anthropology. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez AM, Fuentes L, Allina A. Women or LARC first? Reproductive autonomy and the promotion of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2014;46:171–175. doi: 10.1363/46e1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium A. Digital storytelling: An emergent method for health promotion research and practice. Health Promotion Practice. 2009;10:186–191. doi: 10.1177/1524839909332600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium A, DiFulvio G. Girls in the world: Digital storytelling as a feminist public health approach. Girlhood Studies. 2011;4:28–46. doi: 10.3167/ghs2011.040204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium A, Fiddian-Green A, Hill A. Conflicting aims and minimizing harm: Uncovering experiences of trauma in digital storytelling about sexuality with young women. In: Waycott J, Warr DJ, editors. Ethics for visual research: Theory, methodology and practice. Melbourne, Australia: Palgrave Macmillan; forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium A, Krause E, Jernigan K. Strategic authenticity and voice: Ways of seeing and being seen as young mothers through digital storytelling. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2014;11:337–347. doi: 10.1007/s13178-014-0161-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium A, Peterson JC. Let’s talk about sex: Digital storytelling for Puerto Rican youth. In: Yamasaki J, Geist-Martin P, Sharf BF, editors. Communicating health: Personal, cultural & political complexities. 2. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press; forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium A, Shafer M. Sensual sexuality education with young parenting women. Health Education Research. 2014;29:1–13. doi: 10.1093/her/cyu001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherman T. A space of vulnerability in poverty and health: Political-ecology and biocultural analysis. Ethos. 2011;33:46–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley L, Walsemann K. Sexual orientation and risk of pregnancy among New York city high-school students. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105:1379–1386. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupton D. Toward the development of critical health communication praxis. Health Communication. 1994;6:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C, de Lange N. Community-based participatory video and social action in rural South Africa. In: Margolis E, Pauwels L, editors. The SAGE handbook of visual research methods. London: Sage Publications; 2011. pp. 171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Morse J, Field P. Qualitative research methods. Newbury, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JC, Antony MG, Thomas R. “This right here is all about living”: Communicating the “common sense” about home stability through CBPR and photovoice. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2012;40:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pink S. A multisensory approach to visual methods. In: Margolis E, Pauwels L, editors. The SAGE handbook of visual research methods. London: Sage Publications; 2011. pp. 601–614. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkleton B, Austin E, Cohen M, Chen Y, Fitzgerald E. Effects of a peer-led media literacy curriculum on adolescents’ knowledge and attitudes towards sexual behavior and media portrayals of sex. Health Communication. 2008;23:462–472. doi: 10.1080/10410230802342135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry S. Long distance truckers and the structural context of health: A culture-centered investigation of Indian truckers’ health narratives. Health Communication. 2015;31:230–241. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.947466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States. A portrait of sexuality education and abstinence-only-until-marriage programs in the United States: Fiscal year 2013 edition overview. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.siecus.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&PageID=1427.

- State Community Health Information Profile (StateCHIP) Perinatal trends and health status indicators. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/researcher/community-health/masschip/topics/perinatal-trends.html.

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Sexual orientation and health among US adults: National health interview survey, 2013. 2014 Jul 15; Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr077.pdf.

- Williams T, Pichon L, Campbell B. Sexual health communication within religious African-American families. Health Communication. 2015;30:328–338. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.856743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin R. Case study research: Design and methods. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington, D.C: Sage Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]