Abstract

Objectives

In the 1980’s, policy makers in Mexico led a national family planning initiative focused, in part, on postpartum IUD use. The transformative impact of this initiative is not well known, and is relevant to current efforts in the United States (US) to increase women’s use of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC).

Methods

Using six nationally representative surveys, we illustrate the dramatic expansion of postpartum LARC in Mexico and compare recent estimates of LARC use immediately following delivery through 18 months postpartum to estimates from the US. We also examine unmet demand for postpartum LARC among 321 Mexican-origin women interviewed in a prospective study on postpartum contraception in Texas in 2012, and describe differences in the Mexican and US service environments using a case-study with one of these women.

Results

Between 1987 and 2014, postpartum LARC use in Mexico doubled, increasing from 9% to 19% immediately postpartum and from 13% to 26% by 18 months following delivery. In the US, <0.1% of women used an IUD or implant immediately following delivery and only 9% used one of these methods at 18 months. Among postpartum Mexican-origin women in Texas, 52% of women wanted to use a LARC method at six months following delivery, but only 8% used one. The case study revealed provider and financial barriers to postpartum LARC use.

Conclusions

Some of the strategies used by Mexico’s health authorities in the 1980s, including widespread training of physicians in immediate postpartum insertion of IUDs, could facilitate women’s voluntary initiation of postpartum LARC in the US.

Significance

The long history of postpartum LARC in Mexico is little known outside the country. The widespread availability and acceptance of postpartum LARC in Mexico illuminates the potential demand for this service among Mexican-origin women living in the US. Moreover, Mexico’s concerted effort to make LARC available to postpartum women can serve as an example for the US and other countries seeking to expand voluntary access to highly effective contraception.

Keywords: Mexico, Hispanics, immigrants, postpartum contraception, long-acting reversible contraception (LARC)

INTRODUCTION

In the United States (US), there recently has been considerable interest in expanding access to long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), especially in the postpartum period. Facilitating women’s ability to initiate IUDs and implants immediately following delivery is recognized as a key strategy for reducing short interpregnancy intervals and unintended pregnancy and their associated health risks for mothers and infants (1–3). Recent clinical practice guidelines recommend counseling about LARC as first-line methods and note the safety and efficacy of postpartum insertion (4). Additionally, 18 states have revised their Medicaid policies to allow hospitals to bill the cost of the devices and insertion separately from the global fee for delivery or permit an additional bundled payment (5).

These initiatives come more than three decades after an effort was launched in Mexico to promote immediate postpartum access to highly effective contraception, including the IUD. Surprisingly, though, the Mexican experience with postpartum contraception is not well known in the US or other countries, nor is there much appreciation of just how transformative Mexico’s policy was. Several global reviews of experience promoting postpartum contraception make no mention of Mexico’s experience (6, 7). Additionally, recent studies on changes in US women’s use of or preferences for LARC methods fail to draw a connection between their findings noting the higher prevalence of LARC use among Hispanic women in the US and the pattern of contraceptive practice that was established in Mexico decades ago (8, 9).

In this paper, we consider lessons from Mexican family planning policy initiatives launched in the 1970’s and early 1980s that could be applied in the US to ensure the success of efforts to increase postpartum LARC use. After providing a brief review of Mexican policies, we use a series of Mexican demographic and health surveys to illustrate the dramatic expansion of LARC use and contrast that with a recent analysis of postpartum contraceptive use among US women. Additionally, we examine how the different policy and practice environments in these two countries may affect Mexican immigrant women’s contraceptive preferences and abilities to realize those preferences in Texas, home to one of the largest Mexican-origin populations in the US.

BACKGROUND

Mexico’s Policy To Promote Postpartum Use Of IUDs

In 1973, the Mexican government, led by President Luis Echeverria, adopted a policy to promote family planning and to guarantee its citizens the right to decide freely on the number and spacing of their children. The policy was embedded in the national constitution and institutionalized in a National Population Council (Consejo Nacional de Población [CONAPO]), as well as an authority that would coordinate the various efforts to implement the policy within the main health sector agencies, led by Jorge Martinez Manautou, a distinguished physician and researcher. Demographic targets for the national population growth rate were adopted, as were goals for contraceptive prevalence and, eventually, the method mix (10, 11).

In the initial years of the program, when overall contraceptive prevalence was about 30%, the IUD accounted for about one-sixth of total use among women in union. The program’s later success at increasing use was due to a concerted approach to identify and implement strategies that would facilitate initiation of highly effective methods. For example, over time, the coordinating authority noticed that continuation rates were higher for the IUD than for other methods (12). The next initiative was a study to investigate immediate postpartum insertion of five different types of IUDs in a cohort of 1008 women in the metropolitan area of Mexico City. At the time, the advisability of immediate postpartum IUD use was an unsettled question. The Population Council’s “International Postpartum Family Planning Program,” undertaken in 21 countries in the late 1960s, had yielded disappointingly high expulsion rates (13), yet later studies had shown much lower rates of expulsion using a different insertion technique (14). The 1980 Mexico City postpartum study yielded an expulsion rate of eight percent for the T Cu 220 C, which was in line with the other new studies, and a decision was made to make this option available to all women delivering in public sector hospitals. A major effort was then undertaken to train doctors and nurses attending deliveries in these hospitals to perform immediate postpartum insertions using subsidized devices to ensure the method was available to women across a range of socioeconomic levels. As soon as 1981, postpartum insertions accounted for more than half of all IUD placements undertaken in the hospitals of the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) (12). Overall, IUD use nearly doubled between 1977 and 1987, and most insertions took place in the public sector.

An important of element of the counseling provided to women who had heard rumors about the ineffectiveness or dangerous health consequences of IUD use was to refer them to other women in the community who were using the method successfully (15). In so doing, clinicians helped build the social networks that led to the critical mass of early adopters.

From 1973 to the present, Mexico, like many other countries in Latin America and Asia experienced a dramatic transition in fertility driven by an increase in contraceptive use. Over the last 45 years, the Total Fertility Rate in Mexico fell from over six to near replacement levels, and contraceptive use among women in union increased from 30.2% in 1976 to 71.6% in 2014.1 Over this period, women increasingly came to rely to on just two methods: the IUD and female sterilization (16). Several other countries such as Egypt, Cuba and Vietnam have high prevalence of IUDs (17), but Mexico is unique in the extent to which IUD use is accounted for by postpartum insertions.

US History of LARC Use

In contrast, use of the IUD declined from nearly 10% among women using contraception in the 1970’s to less than 1% in the wake of complications from the Dalkon Shield and subsequent law suits (18, 19). The prevalence of IUD use remained low through the 1990’s and has only recently begun to increase; use of the contraceptive implant, which also had a checkered history in the US, has recently increased as well, but lags behind that of the IUD (10% vs 1%) (20, 21).

What is more, postpartum insertion never gained acceptance by women or providers either before or after the 1970’s. The high price of IUDs and implants in the US, coupled with global fees for delivery with either public or private insurance, has created financial and bureaucratic obstacles that further impede postpartum placements. These structural barriers are reinforced by provider bias (22). In a study of family planning providers in California, only 43% agreed that an IUD can be inserted immediately following delivery (23). This is similar to results from a survey of fellows of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which also found that only 7% of fellows inserted IUDs immediately postpartum (24).

METHODS

We use several data sources to highlight the contrast between the different policy/practice regimes surrounding postpartum LARC in Mexico and the US. To illustrate the increase in postpartum IUD/LARC use in Mexico, we analyzed all of the nationally representative demographic and health surveys conducted in that country since 1987 that included information on the date of the respondent’s delivery, and the dates for her current and previous segment of contraceptive use. We included a total of six surveys, beginning with the 1987 Demographic and Health Survey and ending with recently released 2014 National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica [ENADID]), which are listed in Table 1. For each of the surveys, we computed the weighted percentage of specific contraceptive methods used immediately following delivery, and at three, six, twelve and eighteen months postpartum for all respondents who reported a live birth in the three years preceding the interview; contraceptive methods were grouped into the following categories: female sterilization, vasectomy, LARC (IUDs and implants), hormonal methods (injectables, pills, patch, and ring), and less effective methods (withdrawal, condoms and other barrier methods, and fertility-based awareness methods) (25). This approach is the same as the one we used in our recent analysis of women’s postpartum contraceptive use in the US, which used the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) – a nationally representative survey of women ages 15–44 years (2). We describe those results again here to demonstrate the differences in postpartum contraception in the two countries.

Table 1.

Description of the Mexican demographic and health surveys

| Year | Name of the Survey (Name in English) |

Agency | Sample size |

Sample used in the analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Encuesta Nacional sobre Fecundidad y Salud -- ENFES (Demographic and Health Survey) |

Ministry of Health | 9,310 | 2,352 |

| 1992 | Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica -- ENADID (National Survey of Demographic Dynamics) |

INEGI1 | 69,538 | 17,630 |

| 1995 | Encuesta Nacional de Planificación Familiar -- ENAPLAF (National Family Planning Survey) |

CONAPO2 | 12,720 | 3,075 |

| 2003 | Encuesta Nacional de Salud Reproductiva -- ENSAR (National Survey of Reproductive Health) |

Ministry of Health and CRIM3 |

20,925 | 3,999 |

| 2009 | Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica -- ENADID (National Survey of Demographic Dynamics) |

INEGI | 92,558 | 13,278 |

| 2014 | Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica -- ENADID (National Survey of Demographic Dynamics) |

INEGI | 98,711 | 12,719 |

INEGI: National Institute of Statistic and Geography

CONAPO: National Population Council

CRIM: Regional Center for Multidisciplinary Research

Postpartum Contraception Study, Texas 2012

Information on Mexican-origin women’s unmet demand for postpartum LARC comes from a nine-month prospective cohort study of 803 postpartum women’s contraceptive use in two Texas cities, Austin and El Paso. The study’s methods have been described previously (26), and are summarized briefly here. To be eligible, women had to be 18 – 44 years of age, speak English or Spanish, have delivered a healthy singleton infant that would go home with her at discharge, live within 50 miles of the hospital, and want to wait at least two years before having another child or had completed childbearing. Between April and November 2012, we conducted in-person baseline interviews in the hospital immediately after delivery and contacted women by phone at 3, 6, and 9 months after delivery. Women received $30 for participating in the in-person baseline interview and $15 for each of the follow-up interviews. The institutional review board at the first author’s university approved this study.

Of relevance to the current study, we assessed women’s contraceptive preferences in the baseline and three-month interviews with questions about the method of contraception the participant would like to be using at six months following delivery. We probed for any method the respondent might have omitted because she believed it was not covered by her insurance, or was not available from her provider. We also elicited demand for LARC methods with additional questions at the six-month interview; women who had not previously expressed a preference for LARC were asked whether they would be interested in using an IUD or implant if it were offered for free or low cost. (see (26) for a complete description of the measurement of contraceptive preferences). Finally, at each interview women reported their current method of contraception, if any.

We classified women’s preferred method and current method into four categories, similar to those used in the above-described analyses of the Mexican and US surveys: sterilization (i.e., tubal ligation and vasectomy), LARC, hormonal methods, and less effective methods; we combined female sterilization and vasectomy into a single category given the small number of women reporting vasectomy as their current method. Also, some women had an elicited preference for both LARC and sterilization, and we distinguish those participants from those that expressed an interest in LARC but not in sterilization.

Overall, 709 women (89%) completed the six-month interview on which the present analysis is focused. Approximately 76% of the sample self-reported Hispanic ethnicity. For present purposes, we will only report on the contraceptive preferences and use of the 321 women who were born in Mexico, completed the six-month interview, and who had not yet experienced another pregnancy.

Case study on postpartum contraceptive preferences, Texas 2013

To learn more about the preferences and experiences of the participants in the prospective study, female research assistants, trained in qualitative methods, conducted in-depth interviews with 15 women selected on the basis of having changed their mind about their ideal method of contraception between delivery and 3 months postpartum or having had a consistent preference. The in-depth interview guide focused on participants’ experiences, desires, access and expectations regarding contraceptive use before and after their last delivery, as well as participants’ conversations with providers, partners, family and friends about their preferred contraceptive methods. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish, based on women’s preference, and were recorded and transcribed.

Of the 15 interviews, 9 were with Hispanics. Of them, three were born in Mexico, and one in El Salvador. One of the interviews was with a 39-year-old Mexican immigrant mother of two adolescent boys, recently re-partnered with a younger man, who is the father of her new daughter. Her interview, conducted by one of the authors (CH) and a research assistant, provides an excellent case study contrasting the provision of contraception in Texas, where postpartum LARC is not yet widely available, as compared to Mexico. We summarize her experiences navigating the health care system below.

RESULTS

Postpartum LARC Use in Mexico (1987–2014) versus the US (2006–2010)

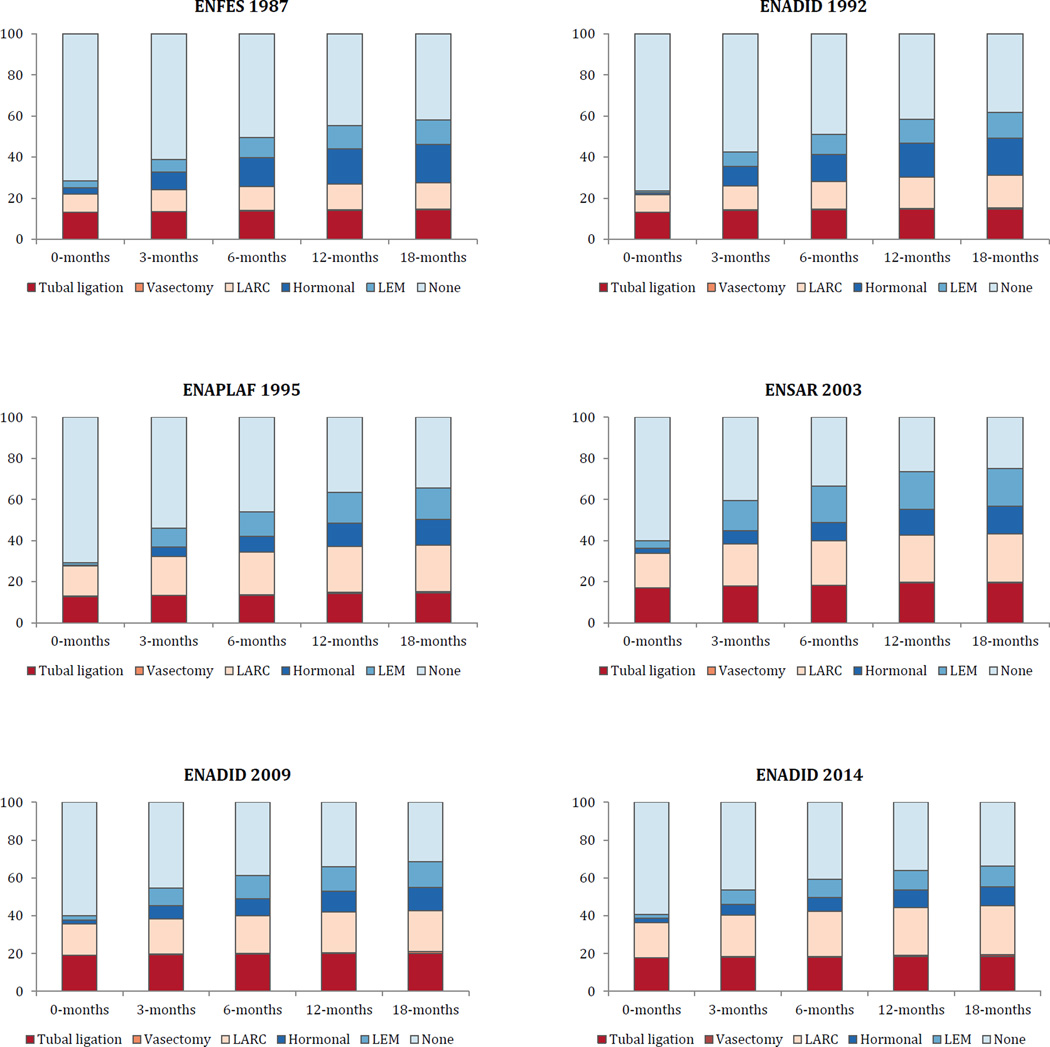

In 1987, postpartum LARC insertions occurred following nine percent of all deliveries in Mexico, and use increased to 13% by 18 months postpartum (Figure 1). The 1992 survey showed no increase in postpartum insertions, but higher use of LARC (16%) at 18 months. The 1995 survey showed postpartum LARC insertions had increased to 15%, and that LARC use at 18 months postpartum was 23%. In the 2003 and 2009 surveys, LARC use remained relatively stable, and then increased to 19% immediately postpartum and 26% at 18 months following delivery in the 2014 survey. Over this 27-year period, the increase in LARC use stemmed from fewer women using hormonal or less effective methods (or no method), and use of female sterilization remained relatively unchanged. Also, in all of these surveys, IUDs accounted for over 95% or more of LARC use.

Figure 1.

Proportions of women in Mexico using each category of method by duration postpartum between 1987 and 2014.

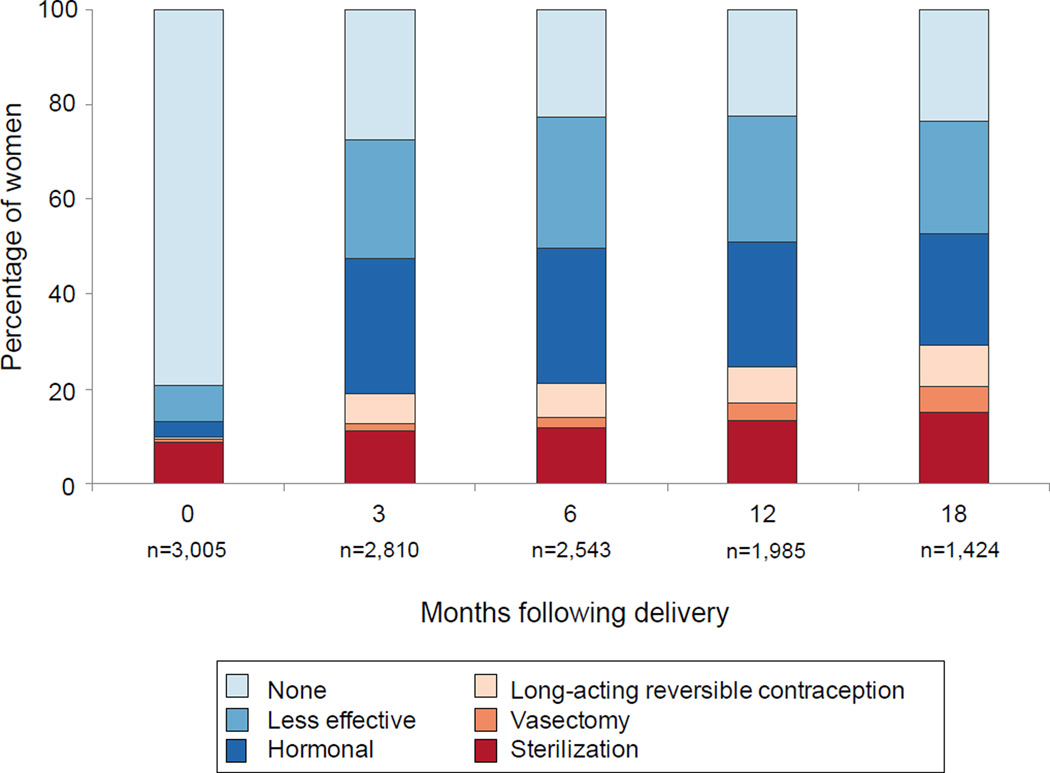

In contrast, there were virtually no postpartum insertions of either IUDs or implants among US women in the 2006–2010 NSFG, with <0.1% of women reporting use of these methods in the month of delivery. At three months postpartum, LARC use increased to six percent, and was only nine percent at 18 months postpartum (2). (see Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Proportions of women in US using each category of method by duration postpartum between 2006 and 2010. (reprinted from White, K., S.B. Teal, and J.E. Potter. 2015. “Contraception After Delivery and Short Interpregnancy Intervals Among Women in the United States.” Obstetrics & Gynecology 125(6):1471–1477)

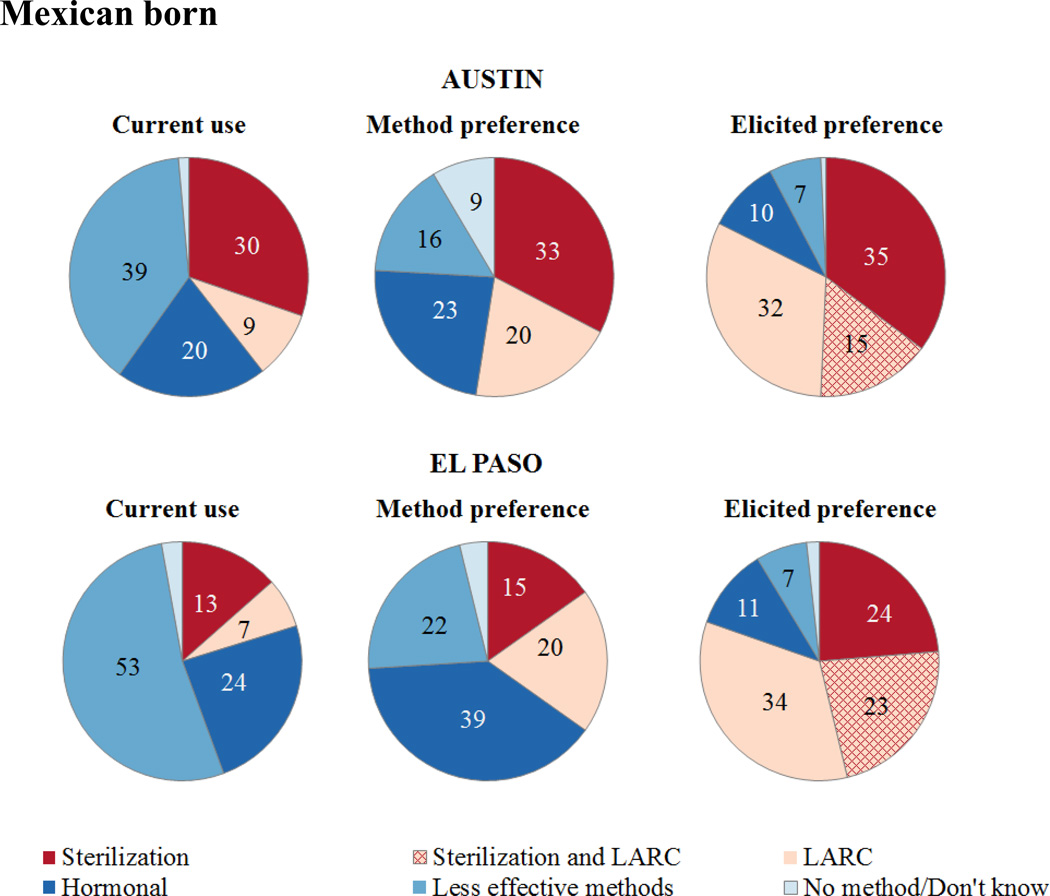

Postpartum Contraception Study, Texas 2012

Among the 321 Mexican-origin women who completed the six-month interview, LARC use is relatively low in both Austin (9%) and El Paso (7%) (Figure 3, left pie chart). Use of hormonal methods is greater, especially in El Paso (24%) where pills, injectables and the patch are available over the counter in pharmacies across the border in Ciudad Juarez. Finally, a very large percentage of women in this study were relying on less effective or no methods. This method mix changed little between the six-month and nine-month interviews (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Current contraceptive use and method preferences at 6 months postpartum among Mexican born women in Austin and El Paso.

The middle pie charts in Figure 3 show women’s contraceptive method preference based on the direct question we asked at the 3-month interview about the method participants said they would like to be using by six months. The preference for LARC far exceeded its actual use in both cities. Using the broader specification of preference incorporating the prompts for interest in LARC and permanent methods (elicited preference), the difference between preference for and actual use of LARC widens considerably (rightmost chart). This last chart distinguishes between women who expressed an interest or demand for LARC but who did not want to be sterilized, and those who did. In Austin, 47% of women expressed an interest in LARC, and about one third wanted to have been sterilized at the time of their last delivery. In El Paso, interest in LARC was found among 57% of women, and 40% of this group also desired a permanent method.

Case study on postpartum contraceptive preferences, Texas 2013

The 39-year-old woman in our case study had used an IUD in Mexico for seven years, prior to having it removed to become pregnant with her new US-born daughter. She had completed two years of university education, but had no insurance at the time of delivery in the US and was still uninsured at six months postpartum. She did not want additional children, and reported in both the baseline and 3-month interviews that she wanted to use an IUD. In the in-depth interview, she explained that this was because she wasn’t very good at taking pills and didn’t like that she had gained weight when she used the injectables, so she “immediately thought about the IUD… because for me, that was really effective.”

However, she encountered several barriers trying to obtain an IUD following her delivery. She was familiar with the Mexican practice of inserting IUDs immediately postpartum, and commented that “over there… after you deliver, the doctor inserts the IUD. He takes advantage of the situation because you’re bleeding, so he inserts the IUD.” Yet, when she inquired during prenatal care about the possibility of getting an IUD in the hospital, her doctor in Texas told her that was not an option and “we could see about that later.” She raised the issue again after her delivery, and this time her doctor told her, “I needed to look for it somewhere else, that it was too expensive, that it cost more than a hundred dollars or something like that. And so, it was surprising to me because in Mexico, they insert it for free. Whether or not you have insurance, there they’ll insert it.” She was not provided with any information on where she could obtain an IUD for free or low cost, and eventually decided to travel back to Mexico to get one.

In contrast to her experiences in the US, getting the IUD in Mexico was easy. She recounted the following details in the in-depth interview:

Participant: “When I got to México, I went [to the IMSS clinic] and they told me to come back the next day because they only insert them in the mornings…the social worker told me that, yes, that method is inserted for free.”

Interviewer: “You just get there and they immediately put you in line?”

Participant: “Yes … You get there, they’re like, ‘What are you here for?’ ‘I’m here to get an IUD,’ ‘Great. What’s your name? Get in line.’ and that’s it. You wait there and then they just call you in and they insert it.”

She later went on to comment that in Mexico “what they want is for you to be (family) planning, …not just to be having children,” and she did not understand why contraception is not available for free in the US when an array of other services are available to help families.

DISCUSSION

The evidence presented in this paper provides a stark juxtaposition of two neighboring countries’ health care systems and the manner with which they make LARC methods available to new mothers in the year following delivery. As US policy makers and clinicians increasingly turn their attention to postpartum LARC use, there are several lessons learned from Mexico’s history that are worth noting. First, Mexico’s emphasis on IUDs was a strategic choice of the authorities coordinating the national family planning program 35 years ago. Now postpartum IUD insertions are a commonplace, and IUDs are the most widely used method of reversible contraception among Mexican women. Despite expansion of health care under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and inclusion of contraceptive coverage without cost sharing, the US lacks a comprehensive federal policy with respect to postpartum contraception. Therefore, much is left to individual states, which has resulted in a patchwork of coverage (27).

Additionally, Mexico’s policies proactively addressed several issues that are emerging as challenges to providing postpartum LARC in US states that permit an increased bundled fee or separate billing for delivery and devices. Specifically, Mexico launched major initiatives to train medical personnel throughout the country in techniques for postpartum IUD insertions that minimized the risk of expulsion – a concern for health systems in the US (28). The cost of devices also was subsidized such that contraception was provided free of charge to Mexican citizens at all levels of the public health care system. Adequate reimbursement for LARC devices provided at the time of delivery is an important barrier to use in the US (28). Expanding provider eligibility for the low-cost levonorgestrel IUD and maintaining appropriate reimbursement for other devices could increase the availability of LARC methods for US women who desire them. This paper also highlights a potentially large unmet demand for postpartum LARC among Mexican-born women in the US stemming from women’s preferences for these methods, on the one hand, and discrepancies between the policy and practice environments in the US and Mexico on the other. This is particularly acute for undocumented migrants. In most states, they are eligible for services paid through Title X, although that program does not cover services at the time of hospital delivery. But they are not eligible for Medicaid, Medicaid waiver programs, or insurance through the ACA. Their exclusion from Medicaid leads to the perplexing arrangement in which their delivery and their infant’s health care are covered by Emergency Medicaid and CHIP, but they are not eligible for contraceptive coverage immediately postpartum or in the 60 days following delivery.

The situation in Texas at the time we conducted our study of postpartum contraceptive use was especially dire. In 2011, the state legislature cut funding for family planning by two-thirds, and instituted a priority system that privileged community health centers and public entities over dedicated family planning providers. This made it extremely difficult for clinics to provide the more expensive methods such as IUDs and implants, and also shifted the remaining funding away from the very clinics that had the most experience providing them (29, 30). These changes affected both undocumented migrants, as well as US citizen and legal residents. Additional funding has been allocated to the state’s family planning program since 2013 and the state recently revised its Medicaid policy to allow reimbursement for postpartum insertion separately from the global delivery fee; however, the extent to which these changes will increase women’s access to LARC methods following delivery likely depends on future efforts to facilitate and encourage adoption of immediate postpartum LARC provision, as well as to extend coverage for the undocumented.

Our review of postpartum LARC use in Mexico also raises other concerns about the relevance of this country’s experience to those interested in increasing access to these methods. Mexico’s policy was initiated more than a decade before the 1994 World Population Conference and widespread concern with demographic targets. While the architects of Mexico’s policy firmly believed in informed consent and the right to decide freely on the number and spacing of children, the extent to which program goals were emphasized over women’s voluntary decision-making has been raised both inside and outside of Mexico (31, 32). Lack of access to wanted LARC methods, rather than coercion, seems to be at issue in our study in Texas. However, in countries like the US that have their own history of coercive contraceptive policies targeting low-income women and women of color (33), additional caution is needed when translating policies and practices to increase women’s use of provider-dependent methods.

In spite of these apprehensions, there is much to admire and perhaps replicate in the process adopted by Martinez Manatou and his colleagues (11). They made a thorough review of the latest available scientific evidence, conducted a local trial, and then embarked on a comprehensive effort to train providers throughout the public health care system. The US has only recently begun to follow a similar path, but it may take a decade or more to train a generation of evidence-based providers and solidify national policies that ensure women have affordable access to their method of choice, which Mexico was able achieve in the early 1980s.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation. Infrastructural support was provided by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24 042849) to the Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

We would like to thank Chloe Dillaway and Natasha Mevs-Korff for superb research assistance.

Footnotes

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Psychosocial Workshop and the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, San Diego, California, April 28-May 2, 2015.

INEGI. 2014. "Consulta interactiva de datos." in Censos y conteos de población y vivienda: INEGI.

REFERENCES

- 1.Teal SB. Postpartum Contraception: Optimizing Interpregnancy Intervals. Contraception. 2014;89(6):487–488. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White K, Teal SB, Potter JE. Contraception After Delivery and Short Interpregnancy Intervals Among Women in the United States. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1471–1477. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiken AR, Creinin M, Kaunitz AM, et al. Global fee prohibits postpartum provision of the most effective reversible methods. Contraception. 2014;90(5):466–467. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: Implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:184–196. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318227f05e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moniz MH, Dalton VK, Davis MM, et al. Characterization of Medicaid policy for immediate postpartum contraception. Contraception. 2015;92(6):523–531. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Programming strategies for postpartum family planning. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleland J, Shah IH. Seminar on Promoting Postpartum and Post-Abortion Family Planning-Challenges and Opportunities. Cochin, India: IUSSP; 2014. [11–13 November 2014;]. Postpartum and Post Abortion Contraception: A Synthesis of the Evidence. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh RH, Rogers RG, Leeman L, et al. Postpartum contraceptive choices among ethnically diverse women in New Mexico. Contraception. 2014;89(6):512–515. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werth SR, Secura GM, Broughton HO, et al. Contraceptive continuation in Hispanic women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;212(3):312 e1–312 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potter JE, Alba F. Population and Development in Mexico since 1940: An Interpretation. Population and Development Review. 1986;12(1):47–75. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez-Manautou J, editor. La Revolucion Demografica en Mexico 1970–1980. Mexico City: Instituto Mexicano de Seguro Social; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aznar R, Lara R, Giner J. Investigacion Biomedica. In: Martinez-Manautou J, editor. La Revolucion Demografica en Mexico 1970–1980. Mexico City: Insituto Mexicano de Seguro Social; 1985. pp. 105–129. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zatuchni GI. International postpartum family planning program: report on an action-research demonstration study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1968;100(7):1028–1041. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(15)33768-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newton J, Harper M, Chan KK. Immediate post-placental insertion of intrauterine contraceptive devices. Lancet. 1977;2(8032):272–274. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90955-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potter JE, Mojarro O, Nunez L. The influence of health care on contraceptive acceptance in rural Mexico. Studies in Family Planning. 1987:144–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potter JE. The persistence of outmoded contraceptive regimes: The cases of Mexico and Brazil. Population and Development Review. 1999;25(4):703-+. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertrand JT, Sullivan TM, Knowles EA, et al. Contraceptive method skew and shifts in method mix in low- and middle-income countries. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2014;40(3):144–153. doi: 10.1363/4014414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurt WG. Septic pregnancy associated with Dalkon Shield intrauterine device. Obstet. Gynecol. 1974;44(4):491–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hubacher D. The checkered history and bright future of intrauterine contraception in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2002;34(2):98–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boonstra H, Duran V, Gamble VN, et al. The 'boom and bust phenomenon': the hopes, dreams and broken promises of the contraceptive revolution. Contraception. 2000;61(1):9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(99)00121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, Finer LB. Changes in use of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods among U.S. women, 2009–2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):917–927. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogburn JA, Espey E, Stonehocker J. Barriers to intrauterine device insertion in postpartum women. Contraception. 2005;72(6):426–429. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biggs MA, Harper CC, Malvin J, et al. Factors influencing the provision of long-acting reversible contraception in California. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):593–602. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luchowski AT, Anderson BL, Power ML, et al. Obstetrician-gynecologists and contraception: practice and opinions about the use of IUDs in nulliparous women, adolescents and other patient populations. Contraception. 2014;89(6):572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trussell J. Contraceptive Failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83(5):397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potter JE, Hopkins K, Aiken AR, et al. Unmet demand for highly effective postpartum contraception in Texas. Contraception. 2014;90(5):488–495. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guttmacher Institute. Laws affecting reproductive health and rights: 2013 state policy review. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moniz MH, Chang T, Davis MM, et al. Medicaid administrator experiences with the implmentation of immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception. Women's Health Issues. 2016;26(3):313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White K, Grossman D, Hopkins K, et al. Cutting family planning in Texas. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(13):1179–1181. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1207920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White K, Hopkins K, Aiken ARA, et al. The impact of reproductive health legislation on family planning clinic services in Texas. Am. J. Public Health. 2015;105(5):851–858. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302515. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bronfman M, López E, Tuirán R. Práctica anticonceptiva y clases sociales en México: la experiencia reciente. Estud Demogr Urbanos Col Mex. 1986;1(2):165–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaccobson JL. Transforming family planning programmes: Towards a framework for advancing the reproductive rights agenda. Reproductive Health Matters. 2000;8(15):21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(00)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomez AM, Fuentes L, Allina A. Women or LARC first? Reproductive autonomy and the promotion of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):171–175. doi: 10.1363/46e1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]