Abstract

The rational engineering of photosensor proteins underpins the field of optogenetics, in which light is used for spatio-temporal control of cell signalling. Optogenetic elements function by converting electronic excitation of an embedded chromophore into structural changes on the microseconds to seconds timescale, which then modulate the activity of output domains responsible for biological signalling. Using time resolved vibrational spectroscopy coupled with isotope labelling we have mapped the structural evolution of the LOV2 domain of the flavin binding phototropin Avena sativa (AsLOV2) over 10 decades of time, reporting structural dynamics between 100 femtoseconds and one millisecond after optical excitation. The transient vibrational spectra contain contributions from both the flavin chromophore and the surrounding protein matrix. These contributions are resolved and assigned through the study of four different isotopically labelled samples. High signal-to-noise data permit the detailed analysis of kinetics associated with the light activated structural evolution. A pathway for the photocycle consistent with the data is proposed. The earliest events occur in the flavin binding pocket, where a sub-picosecond perturbation of the protein matrix occurs. In this perturbed environment the previously characterised reaction between triplet state isoalloxazine and an adjacent cysteine leads to formation of the adduct state; this step is shown to exhibit dispersive kinetics. This reaction promotes coupling of the optical excitation to successive time-dependent structural changes, initially in the β-sheet then α-helix regions of the AsLOV2 domain, which ultimately gives rise to Jα-helix unfolding, yielding the signalling state. This model is tested through point mutagenesis, elucidating in particular the key mediating role played by Q513.

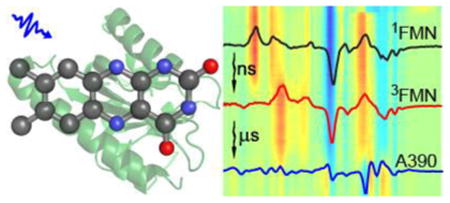

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The LOV (light-oxygen-voltage) domain is a versatile blue light sensing flavoprotein motif found in plants, fungi and bacteria. This modular unit is coupled to a diverse range of signalling output domains and thus involved in the optical control of a variety of functions, including the phototropic response, circadian rhythms and gene expression.1-5 This combination of diversity and modular nature led to the adoption of the LOV domain as a key element in optogenetics, where light induced structure change has been recruited to optically regulate a range of activities, such as the tryptophan repressor,6 dihydrofolate reductase7 and GTPase RAC1,8 among others.9-10 Consequently, there is wide interest in establishing a detailed microscopic picture of its light sensing mechanism, from both a fundamental point of view and to facilitate the rational engineering of new optogenetic applications.

The LOV domain is a member of the Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) superfamily, specifically of a subfamily which binds a flavin molecule in a binding pocket well protected from the surrounding medium (Fig. 1). The isoalloxazine unit of the flavin mononucleotide cofactor (FMN, see Supporting Information (SI) Fig. S1 for structure) acts as the chromophore, absorbing light at about 450 nm in the unilluminated (dark) state. Following singlet state excitation the flavin triplet state is formed and reacts (via a mechanism which has yet to be fully characterised) with a conserved cysteine residue, generating a covalent bond between the cysteine sulfur and the C4a atom of the isoalloxazine chromophore (Fig. S1 for atom numbering). This cysteinyl adduct absorbs at 390 nm (hence designated A390) and spontaneously reverts to the dark state in minutes to hours, depending on the particular LOV domain.11-16 Formation of A390 initiates further structural evolution in the protein, with the initial step suggested to involve local reorganization of the H-bond network adjacent to the isoalloxazine chromophore (Fig. 1). The resulting structure change, characterised by X-ray and NMR, can be extensive and is a function of the specific output domain.3, 17-21 The focus of this study is the LOV2 domain of Avena sativa phototropin (AsLOV2) in which a Jα-helix bound to the β-sheet in the dark state (Fig. 1) unbinds under irradiation and ultimately unfolds.20,17

Figure 1. Structure of the AsLOV2 domain.

A. The Flavin cofactor is shown bound to the β-sheet (olive) with the Jα-helix in yellow. B. Details of the H-bonding network surrounding FMN.

Here we probe in real-time the structural dynamics of AsLOV2 in deuterated buffer using a recently developed time-resolved multiple probe spectroscopy (TRMPS) experiment which measures time resolved infra-red (TRIR) difference spectra with high signal-to-noise and 100 fs time resolution between 100 fs and 1 ms after optical excitation.22 This allows resolution of intermediate spectra over ten decades of time, and thus the accurate determination of kinetics in the AsLOV2 photocycle. The temporally evolving chromophore (FMN) and amino acid vibrational modes are resolved and assigned by isotope editing, providing mechanistic detail, and the mechanism is probed further through mutagenesis. Together these experiments highlight the role of complex kinetics and protein-chromophore interactions in the LOV domain photocycle. Our measurements build on earlier high quality IR studies of LOV domains. Kandori and co-workers investigated hydrated films of AsLOV2 as a function of temperature. They recorded changes in structure between dark and signalling states, including significant structural perturbation in the β-sheet, associated with an initial reorientation of a highly conserved glutamine residue, with subsequent unfolding of the Jα-helix.19, 23-24 Using step scan FTIR, Heberle and co-workers observed distinct phases in the LOV domain temporal response to formation of A390, ranging from microseconds to several milliseconds.25-26 Other relevant time resolved studies of LOV domains include IR studies on the picosecond timescale and electronic spectroscopy on the femtosecond to nanosecond time domain, which resolved triplet formation and decay.14, 27 These have very recently been complemented by studies extending to the microsecond time domain through electronic and infra-red spectroscopy.28-29 Kutta et al. showed that formation of A390 occurs without a kinetically resolved intermediate,28 while Konold et al. showed that adduct formation occurs in microseconds and is followed by slower kinetics, assigned to unfolding of the Jα-helix in 200 microseconds.29 Uniquely, the TRMPS method enables the entire photocycle to be visualized in one experiment with very high signal-to-noise. Interrogation of TRMPS data using isotope-labelling and site-directed mutagenesis then enables the mechanism of photoactivation to be delineated in unprecedented detail.

Experimental

Time Resolved Multiple Probe Spectroscopy (TRMPS) Measurements

The femtosecond to millisecond time resolved infra-red (TRIR) data were recorded using the time resolved multiple probe spectroscopy (TRMPS) apparatus recently developed at the Central Laser Facility. This has been described in detail elsewhere,22 but essentially allows the measurement of high signal-to-noise (<10 μOD) IR difference spectra with <100 fs time resolution at delay times between 100 fs and 1 ms after electronic excitation of the sample. The apparatus uses a combination of optical and electronic delays to cover the complete time range. In the present experiments excitation was by an OPA, pumped by an amplified Ti:Sapphire laser operating at 1 kHz, delivering 450 nm pulses of < 1 μJ energy and 100 fs duration at the sample, focused to a 100 μm spot size; spectra and kinetics were measured to be independent of excitation energy in this regime. This excitation source was synchronised with a 10 kHz amplified Ti:Sapphire laser, which pumps optical parametric amplifiers, the output of which is mixed to generate the broadband IR pulses used as the probe. The TRIR spectra are collected by multiplex measurements such that 10 spectra are acquired for each excitation pulse. The samples (all at a concentration of 1-2 mM) were contained in a 50 μm pathlength flow cell, which was itself rastered in the beam such that a fresh sample was illuminated by each excitation pulse and the entire sample volume was exchanged in each raster cycle. The temperature was 295 K. Experimental data are shown in Figure 2 and 3. These data were reproducible over multiple samples prepared in two labs (USA and Germany). The reproducibility of the analysis is reported in Supplementary Table 1. Data used to generate the figures shown is available from the corresponding authors.

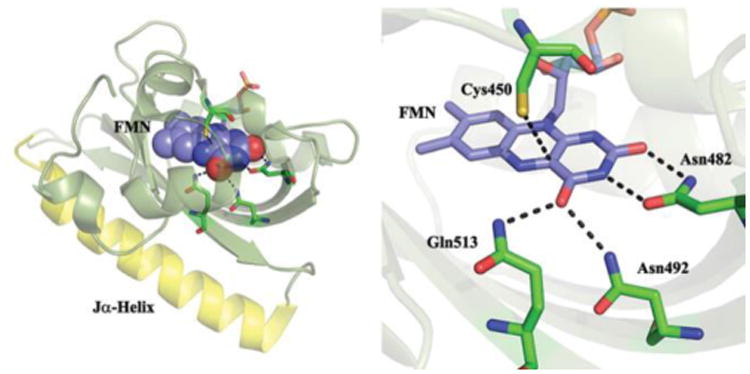

Figure 2. TRIR difference spectra of AsLOV2 between 1 ps and 100 μs.

A. Upper panel, the experimental TRIR spectra for FMN in buffer at 2 ps (black) and 50 ns (red) compared (lower panel) with key stages in the AsLOV2 photocycle (2 ps; red, 50 ns; blue, 100 μs; green). 2B. The 100 μs TRIR spectrum of AsLOV2 compared with the steady state FTIR difference spectrum recorded after continuous irradiation. C. A 2D a red-blue ‘heatmap’ representation of the complete TRIR data showing three distinct regions ascribed to singlet, triplet and adduct. Yellow – red indicates a transient absorption, blue a bleach.

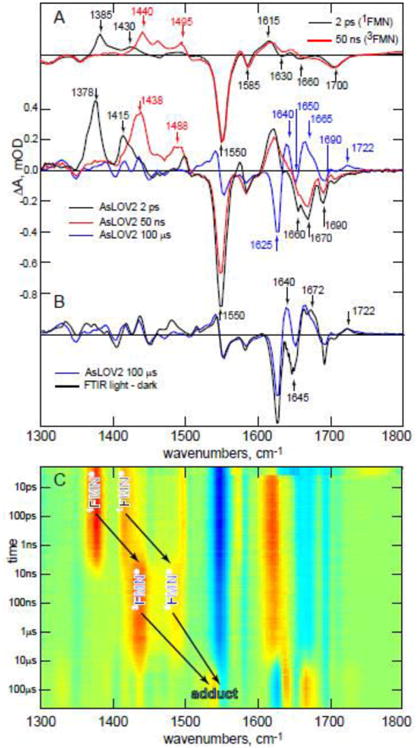

Figure 3. Experimental TRIR data for AsLOV2 and Four Isotopologues.

A. Wild Type AsLOV2 (see also Figure 2). B. [apoprotein-13C]-AsLOV2. C. [2-13C]-FMN, D. [4,10a-13C2]-FMN, E. [U-13C17]-FMN. The data are shown as heat maps (blue for bleach, red for transient absorption) with a logarithmic timescale, where the evolution from singlet to triplet to A390 is clear and the experimentally observed changes resulting from isotope labelling are apparent.

Sample Preparation

(i) Wild-type AsLOV2 Expression and Purification

The codon optimized gene encoding C-terminal LOV2 domain of Avena sativa phototropin 1 (commonly referred to as AsLOV2) containing residues 404-546 was sub-cloned into pET15b vector using pTrixEx-mCherry-PA-RAC1-T17N as a template. NcoI and BamHI restriction sites were used including N-terminal 6x-His tag in the construct. The resulting plasmid was transformed into BL21 (DE3) E. coli cells for protein expression and a single colony was used to inoculate a 10 mL culture of LB media supplemented with ampicillin (Amp) at 200μg/mL. After incubating the culture at 37 °C and 250 rpm overnight, it was used to inoculate 1 L of 2× YT/Amp media in a 4 L flask. The 4 L flask was shaken at 37 °C and 250 rpm until the OD600 reached ∼0.8. The temperature was decreased to 20 °C followed by addition of 0.8 mM IPTG to induce protein expression overnight (∼16 h) in the dark. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C and 5000 rpm and stored at -20 °C.

The cell pellet resulting from a 1 L culture was thawed and resuspended in 40 mL of buffer A (20mM Tris, 150mM NaCl pH 8.0) supplemented with 200 μL of the protease inhibitor, phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride (PMSF; 50 mM stock solution in ethanol), and 14 μL of β-mercaptoethanol. The cells were then lysed using a high-pressure cell disruptor (Constant Systems, Model E1061) at 30 kpsi with the pressure cell temperature controlled at 4 °C. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (40,000 rpm for 90 min). The supernatant was incubated with FMN (0.25 mg/mL) for ∼30 min on ice and in the dark to ensure a homogeneous population of protein bound chromophore followed by loading it onto a column with Ni-NTA resin previously equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with buffer A containing increasing concentrations of imidazole (0 mM, 10 mM and 20 mM) until AsLOV2 eluted at 250 mM imidazole. The protein was dialyzed overnight against buffer A and its purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE. In order to exchange the protein into D2O, AsLOV2 samples were frozen in liquid N2, lyophilized overnight, and re-dissolved in D2O. The cycle was repeated twice after which the protein at concentration of about 100 μM was equilibrated in D2O buffer for at least a week to ensure full exchange of all protons.

(ii) Preparation of AsLOV2 Q513A, Q513L, and C450V mutants

Site-directed mutagenesis was used to introduce Q513A, Q513L, and C450V mutations into a plasmid carrying the gene for AsLOV2 (residues 404-546 in pet15b vector) using the following primers:

Q513A

5′-TAC TTT ATT GGG GTT GCG TTG GAT GGA ACT GAG-3′ (forward)

5′-CTC AGT TCC ATC CAA CGC AAC CCC AAT AAA GTA-3′ (reverse)

Q513L

5′-TAC TTT ATT GGG GTT CTG TTG GAT GGA ACT GAG-3′ (forward)

5′-CTC AGT TCC ATC CAA CAG AAC CCC AAT AAA GTA-3′ (reverse)

C450V

5′-ATT TTG GGA AGA AAC GTG AGG TTT CTA CAA GGT-3′ (forward)

5′-ACC TTG TAG AAA CCT CAC GTT TCT TCC CAA AAT-3′ (reverse)

After verifying the sequence of the constructs (AsLOV2 Q513A, AsLOV2 Q513L, and AsLOV2 C450V), protein expression and purification was performed as described for wild type AsLOV2.

(iii) Isotopic Labeling of AsLOV2

Reagents

[2-13C1] Riboflavin and [4,10a-13C2] riboflavin were prepared by the procedure of Tishler et al..30 [U-13C17] Riboflavin was produced by biotransformation of [U-13C6] glucose.31

Preparation of AsLOV2 Isotopologues

13C-Labeled protein samples were produced using a recombinant Escherichia coli strain that contained a plasmid directing the low-level expression of a bacterial riboflavin transporter32 and with a second plasmid directing the high-level expression of AsLOV2. For the production of proteins carrying labelled FMN, the strain was cultured with a supplement (7 mg L-1) of 13C-labeled riboflavin. For the production of [apoprotein-U-13C]-AsLOV2, the recombinant E. coli strain was grown with [U13C6] glucose as the exclusive carbon source; unlabelled riboflavin was added to the culture medium at a concentration of 7 mg L-1. Isotopolog replacement is achieved with a purity greater than 95% in this method32 and no 12C labelled flavins were detected in mass spectrometry.

Steady-State FTIR Spectroscopy

Light minus dark IR spectra of wild type AsLOV2 and multiple isotopically labeled samples were obtained on a Vertex 80v (Bruker) FTIR spectrometer with 1 cm-1 resolution. Eighty μL of 1-2 mM protein sample in D2O buffer (20mM Tris, 150mM NaCl pD 8.0) was placed between two CaF2 windows with a 50 μm spacer and into a Harrick cell for the measurement. The light adapted state was generated by 3 min irradiation using a 460 nm high power mounted LED (Prizmatix, Ltd.) placed in the sample compartment and focused onto the cell using an objective. The temperature of the sample holder was controlled using a circulating water bath and data were acquired at 20 °C.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Absorption spectra of all protein samples were obtained using a UV-Vis spectrometer (Cary 100 Bio) at 20 °C. The concentration of the protein samples was kept at around 80 μM in either H2O or D2O buffer (20mM Tris, 150mM NaCl pH/D 8.0). Dark-adapted spectra were obtained first and then in order to acquire a light state spectra, samples were illuminated with ∼500 mW in approx. 1 cm2 of 455 nm light (20 nm bandwidth) for about 1 minute. Recovery of the dark state from the light state was measured with scanning kinetics followed by plotting the change in the absorbance at 447 nm over time and fitting to a single exponential decay equation.

Data Analysis Methods: Global Analysis

All measured time resolved spectra were subject to global analysis (GA). The GA procedure simultaneously fits kinetic traces at all measured wavenumbers to a sum of exponential decays convoluted with the instrument response function (IRF). The simplest forms of GA use models with a number of components, either decaying in parallel, which results in decay associated spectra (DAS), or in a sequential manner, which results in evolution associated spectra (EAS). The DAS represent estimated spectral amplitudes of each kinetic component. In most cases DAS are a pure mathematical decomposition of the data that do not represent real physical/chemical species. The EAS represent the evolution of the spectra in time but also do not necessarily represent real physical/chemical species. In more advanced forms of GA full kinetic model may be applied (e.g. Fig. S2, see below) and in that case each microscopic rate constant represents the transfer of one state/species into another, or the decay to the ground state. The spectra estimated from such analyses are called species associated spectra (SAS) and are assumed to represent the pure physical/chemical state/species in the kinetic model. However, the estimated SAS depend strongly on the adequacy of the applied model, and whether or not the different species can be kinetically or spectrally estimated. The global and target analysis in the present paper was performed using the free and open source program Glotaran33. In most cases we report the results of data which were well fit by the sequential model yielding EAS, although some SAS analyses were attempted these proved less satisfactory and physically less meaningful (See Fig. S2 and associated discussion). The results of the individual analyses are given in Table S1.

Results and Discussion

Kinetics of the LOV Photocycle

Fig. 2 shows experimental TRIR data for AsLOV2 in deuterated buffer. Fig. 2A shows spectra recorded 2 ps, 50 ns and 100 μs after excitation, compared with the cognate 2 ps and 50 ns TRIR spectra for FMN in D2O. Fig. 2B compares the 100 μs TRIR spectrum with the steady state (light minus dark) FTIR difference spectrum of AsLOV2. Fig. 2C shows the complete temporal evolution of the TRIR spectra of AsLOV2, with t = 0 defined as excitation of the isoalloxazine chromophore by a 450 nm sub-100 fs ‘pump’ pulse. The TRIR difference spectra comprise negative and positive bands (Fig. 2A). The negative bands (bleaches) are associated with depletion of the isoalloxazine singlet ground state, or with changes in the vibrational spectrum of the surrounding protein occurring instantaneously (as a result of chromophore excitation) or as a result of subsequent structural dynamics. The positive bands (transient absorptions) arise due to vibrations of the electronically excited states of isoalloxazine, to amino acid modes perturbed by electronic excitation or to vibrational modes of products formed following excitation.

Fig. 2A shows marked differences between TRIR spectra of aqueous FMN and AsLOV2, with the latter revealing much richer structure in the 1600 – 1750 cm-1 region. The vibrational spectrum of FMN itself has been assigned;34-36 the bleaches at 1660 cm-1 and 1700 cm-1 (Fig. 2A) are associated with C=O vibrations of isoalloxazine, which comprise a coupled pair with the higher wavenumber mode more localized on C4=O and the lower on C2=O. The next two bleaches at lower wavenumber (1630, 1585 cm-1) are ring modes with significant C4aN5 stretch contributions, and the most intense bleach (1550 cm-1) is a C10aN1 dominated mode.34-36 The three transient absorptions (1385, 1430, 1615 cm-1) in the 2 ps spectrum are due to vibrations of the FMN singlet excited state, 1FMN*. Significantly, two additional bleaches are well resolved in the 2 ps spectrum of AsLOV2 (at 1690 and 1670 cm-1), which must arise from vibrational modes of amino acids interacting with the chromophore. Their appearance in the earliest difference spectra indicates that the amino acid/chromophore interaction is modified instantaneously (within the 100 fs time resolution) by electronic excitation. We suggest that changes in electron density distribution between ground and excited states modify the strength of H-bonds, modifying in-turn amplitudes and frequencies of the vibrational modes of adjacent amino acid residues.37

As 1FMN* decays, the triplet state (3FMN) is formed (the 1438 and 1488 cm-1 transients in the 50 ns spectrum are characteristic), which then reacts with C450 to form the A390 adduct.16 The 100 μs TRIR spectrum (Fig. 2B) is profoundly different to that at 2 ps, as expected for formation of the chemically distinct A390.38 Finally, comparison with the steady state IR difference spectrum (Fig. 2B) shows that while many important changes in the photocycle occurred within the first 100 μs, further evolution occurs on a longer timescale, most notably near 1640 cm-1 (see below and ref. 26). Fig. 2C shows the complete temporal evolution during the LOV photocycle. These data are consistent with the mechanism proposed through studies of electronic spectra;2, 14, 28, 38-39 1FMN* (characteristic transients shifted to 1378 and 1415 cm-1 in the protein) decays in nanoseconds to form 3FMN (characterized by growth of transient absorption at 1438 and 1488 cm-1) which then reacts in microseconds to form A390.

The evolution in vibrational spectra provides insight into structural changes in the protein required to understand formation of the signaling state. The changes in vibrational spectra between singlet and triplet are mainly associated with the chromophore, while bleaches associated with perturbed amino acid residues (e.g. the previously noted 1670 and 1690 cm-1) are unaltered. In contrast, there are large changes in both chromophore and protein amino acid modes upon adduct formation, consistent with a major structural transformation. Changes include new bleaches at 1625 and 1650 cm-1 and three transients at 1640, 1665 and 1722 cm-1, with several smaller changes in the 1400 – 1600 cm-1 range (Fig. 2A). The A390 formation, characterized by these new vibrational modes, is not seen in the C450V mutant, where instead the triplet lifetime is greatly extended; this is consistent with A390 arising from a reaction between 3FMN and C450 (mutant data are discussed further below).

The TRIR measurement in Fig. 2C was repeated for the U-13C labelled apoprotein of AsLOV2 loaded with unlabelled FMN (designated [apoprotein-13C]-AsLOV2) and for AsLOV2 with unlabeled apoprotein reconstituted with [2-13C1]-, [4,10a-13C2]- or [U-13C17]-FMN (Fig. 3); the isotope shifts are discussed in the next section. Separate global analyses of all five of these samples in terms of an unbranched sequential kinetics model required the same number of time constants which were the same within experimental error (the global analysis procedures are presented in methods below and the results from the five separate analyses in SI Table S1). Significantly, these separate analyses of wild type protein all required two steps in the photocycle associated with the 3FMN to A390 reaction. The absence of a kinetic isotope effect allows a parallel global analysis of all five data sets for enhanced precision in the time constants (Fig. 4, Table 1). This reveals that 3FMN is formed from 1FMN* in 2.4 ns. The 3FMN then relaxes in an apparent two-step fashion with time constants of 9.5 μs and 17 μs to form A390 (the quality of fit data showing the requirement for a second component are included in Figure S2). The evolution associated spectra (EAS, see methods) at 9.5 μs contains vibrational modes characteristic of both 3FMN and A390. This requirement for an additional component between 3FMN and A390 does not therefore indicate resolution of any chemically distinct intermediate. The mechanism of formation of A390 has been discussed in terms of initial H atom or proton/electron transfer steps, or a concerted mechanism.39 Either intermediate species would yield distinct signatures in TRIR,40 which are not observed; the 9 μs EAS only has features of 3FMN and A390, not of any new modes. The absence of an observable intermediate suggests that the rate determining step in A390 formation is the initial reaction between C450 and 3FMN, with any subsequent steps occurring on the submicrosecond timescale; this is in accord with Kutta et al.28

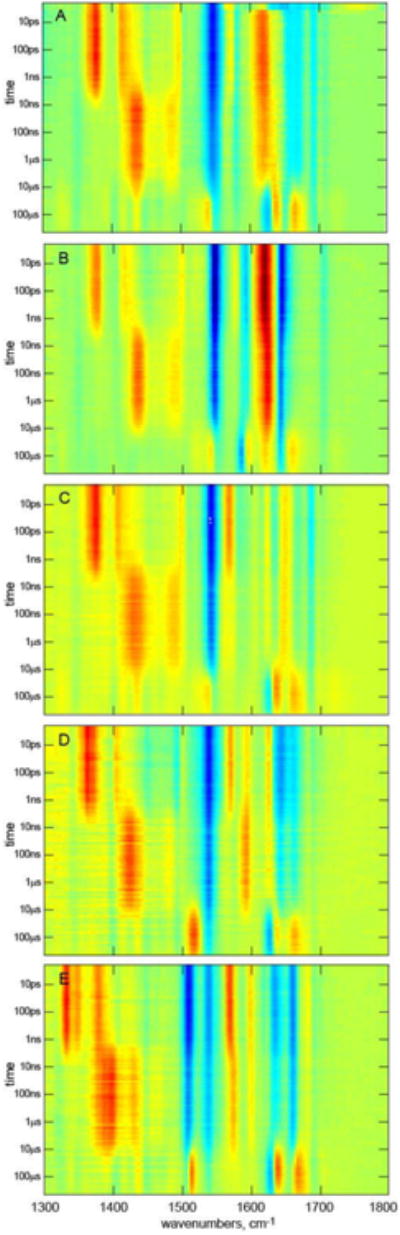

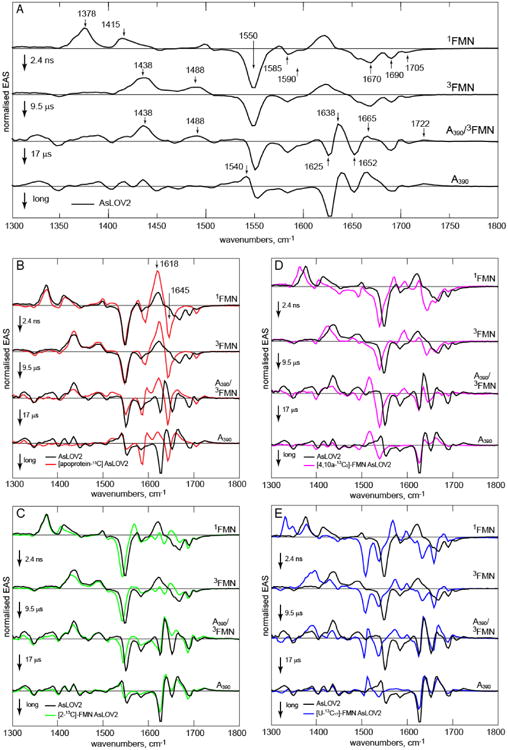

Figure 4. EAS from Analysis of TRIR of AsLOV2 and Isotopologues.

The EAS for the sequential kinetics model 1FMN*→3FMN→3FMN/A390→A390. A Wild Type AsLOV2, with wavenumber labels used in text shown. In each subsequent pane the wild Type EAS are compared with the isotopologue. B. [apoprotein-13C]-AsLOV2, C. [2-13C]-FMN, D. [4,10a-13C2]-FMN, E. [U-13C17]-FMN.

Table 1. Time constants resulting from global fitsa.

| AsLOV2 | τ1/ns | τ2/μs | τ3/μs | τ4/μs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTb | 2.4 | 9.5 | 17 | >500 |

| Q513A | 2.1 | 5 | 16 | >500 |

| Q513L | 1.8 | 4.7 | c | >500 |

| C450Vd | 3.5 | 0.03 | 98 |

Accuracy of all time constants better than ±5%.

Results from a parallel fit to 5 isotopologues.

Second component not detected,

Second fast component required to fit the data, suggesting departure from exponential relaxation at early time.

Two related non-sequential models of the two-step kinetics for 3FMN to A390 were considered. One invokes different pathways from 3FMN to A390, associated with distinct orientations of C450. This is plausible, based on the observation of two orientations of C450 in the crystal structure.17 However, a global fit to this model resulted in very different EAS for the two fundamentally similar 3FMN states, which is unrealistic (Fig. S2). The extreme form of this model is that one C450 orientation does not lead to reaction at all, but returns to the ground state. In this case the 9.5 μs component recovered is too fast for decay of an unquenched triplet state (especially in the light of the very long lived 3FMN resolved in C450V, Table 1). Thus, the sequential model provides the best description of the data.

As noted above, the 9 μs EAS has features of both 3FMN and A390 (Fig. 4). Specifically, among A390 modes the 1722 cm-1 C4=O transient (see below for assignment) appears in both 9.5 and 17 μs EAS, while the 1540 cm-1 transient is only fully developed in the 17 μs EAS. The 1665 cm-1 transient, which comprises both FMN and protein contributions, and the 1625 cm-1 protein bleach both have very different amplitudes in the two EAS (Fig. S3). From this mixed character we suggest that these two EAS should not be interpreted as reflecting two distinct kinetic steps involving an additional intermediate state, but rather as averaged spectra representative of multistep or dispersive kinetics leading from 3FMN to A390. Dispersive kinetics are a feature of protein folding dynamics, and arise naturally from roughness in an energy landscape.41 The present data may be interpreted with a similar model, but now applied to the dynamics of sub-millisecond optically induced conformational change. Thus, we assign the dispersive kinetics to a model in which the protein structure visits multiple metastable trap states on an energetically downhill pathway to the relaxed A390 state.41 We note that step scan FTIR data also revealed two-state adduct kinetics (20 μs and 52 ms, the former being in good agreement with the 17 μs resolved here).26 These data then point to a very wide range of kinetics in the AsLOV2 photocycle, to be probed further here by isotope labelling.

Isotope Labelled AsLOV2

In addition to [apoprotein-13C]-AsLOV2, obtained by growing the recombinant E. coli strain with [U-13C6] glucose and unlabelled riboflavin, protein samples carrying 13C-labels of the FMN chromophore were obtained by in vivo loading of a recombinant Escherichia coli strain with 13C isotopologues of riboflavin affording [2-13C1]-AsLOV2, [4,10a-13C2]-AsLOV2 and [U-13C17]-AsLOV2 (details are presented in methods below). Fig. 3 shows the experimental data for each sample. Qualitatively the evolution from 1FMN*→3FMN→A390 is apparent in Fig 3 A-D, with transient signals at 1380 cm-1 decaying to a transient at 1438 cm-1 and, after 10 μs the appearance of three transients characteristic of A390. The data for [U-13C17]-FMN are more perturbed but show the same qualitative trend and kinetics (Table S1). There are striking differences between Fig 3A and B revealing a key role for protein modes in the TRIR data, while Fig. 3C-E allow better discrimination of chromophore modes from modes of the perturbed protein backbone. However, these comparisons are best made on the basis of the EAS (Fig. 4).

EAS from the global kinetic analysis of the complete TRIR data for wild type AsLOV2 are shown in Fig. 4A, while in Figs 4 B-E the wild type EAS are compared with the four isotopically labelled samples. The comparison with [apoprotein-13C]-AsLOV2 (Fig 4B) resolves contributions to the TRIR spectra of vibrational modes associated with the chromophore from those due to surrounding amino acid residues perturbed by electronic excitation. The first EAS is associated with 1FMN*. The major changes induced by 13C exchange occur above 1600 cm-1, which confirms the contribution of amino acid modes in that region, in addition to the expected two FMN C=O mode contributions29. In particular, the 1690 and 1670 cm-1 bleaches are downshifted in [apoprotein-13C]-AsLOV2 to merge with and contribute to the intense 1645(-)/1618(+) pair, which overlaps the 1615 cm-1 isoalloxazine transient absorption. Further these modes are present in Figs 4C and D, so they must therefore be of amino acid rather than isoalloxazine origin. In contrast, modes below 1600 cm-1 are unshifted in the first EAS in Fig 4B and barely shifted in 4C and D, demonstrating that they are dominated by isoalloxazine vibrations; the larger perturbation of these transitions at lower wavenumber in Fig 4E suggests that they arise from ring modes of isoalloxazine. The peak at 1705 cm-1 which is unshifted in 4B, C is the C4=O localised isoalloxazine mode (confirmed by the shift [4,10a-13C2]-AsLOV2, Fig, 4D). The downshift of the 1670 cm-1 protein mode suggests that the expected isoalloxazine C2=O mode (see Fig. 2A) in AsLOV2 must have been obscured by it; as a check, polarization resolved experiments were performed which indeed reveal the wild type 1670 cm-1 mode to be composite (Fig S4). Thus, we assign the shoulder seen at 1660 cm-1 in wild type, and revealed unshifted in the [apoprotein-13C]-AsLOV2 EAS, to the C2=O localized isoalloxazine mode which is supported by the [2-13C]-AsLOV2, data Fig. 3C.

The major contributions from perturbed amino acid modes occur at wavenumber >1660 cm-1, which is too high to be assigned to amide I vibrations, so the most plausible assignment for the 1690 and 1670 cm-1 bleaches is to carbonyl containing sidechains which interact with isoalloxazine. The X-ray structure of AsLOV2 (Fig. 1) suggests a prime candidate to be the conserved glutamine residue, Q513 (Fig. 1), which had already been proposed to be involved in triggering protein structure change.19, 42

The second EAS reflects formation of 3FMN. The main changes are associated with isoalloxazine transient absorptions, with negligible changes in modes >1600 cm-1; the amino acid modes perturbed on electronic excitation are unaffected by intersystem crossing (Figs 3,4). The first phase of the reaction between 3FMN and the adjacent C450 to form A390 is characterized by spectral evolution from the second to third EAS. The latter comprises both triplet modes (1438, 1488 cm-1) and modes associated with formation of the final A390 state. As discussed above this mixed character is assigned to a spectroscopic manifestation of underlying dispersive kinetics. A transient at 1722 cm-1 unshifted in [apoprotein-13C]-AsLOV2 (Fig 4B) but absent in 4E, is assigned to the C4=O mode of A390, the increase in frequency results from a loss of conjugation, consistent with the observed blue shift in electronic spectra.13 The protein bleach at 1690 cm-1 observed in the first EAS is unshifted by formation of A390, while that at 1670 cm-1 is now obscured by a new transient at 1665 cm-1. This transient is present in [apoprotein-13C]-AsLOV2, suggesting it arises from A390. Significantly, in the same EAS a new transient appears at 1638 cm-1 with concomitant bleaches at 1625 and 1652 cm-1. All three are uniformly shifted down in frequency in [apoprotein-13C]-AsLOV2 (Fig. 4B), suggesting they arise from changes in the protein structure induced as a result of A390 formation. Thus the onset of A390 formation already has a large effect on the protein vibrational spectrum.

The second phase of A390 formation is characterized by a 17 μs time constant and reveals further evolution in the distribution of the higher wavenumber protein modes, most notably a strongly increasing bleach at 1625 cm-1. These kinetics show that evolution in the protein structure occurs on the microsecond timescale, while the wavenumber (1625 cm-1) suggests assignment to a structural perturbation of a β–sheet amide I mode (which are observed in the 1615 – 1645 cm-1 range in D2O 43); this is consistent with the simulations of Peter et al. who report that A390 formation leads to reorganisation of Q513 which transmits stress to adjacent β-strands.42 These changes in protein structure are accompanied by formation of a new transient at 1540 cm-1 near to the intense 1550 cm-1 isoalloxazine bleach; this transient is of mixed character, showing a small shape change on [apoprotein-13C] substitution, while the TRIR of three samples with 13C labelled flavin cofactors (Fig. 4C-E) confirm it is associated with A390 formation. This is consistent with changes in protein structure and A390 formation occurring simultaneously, reflecting dispersive kinetics.

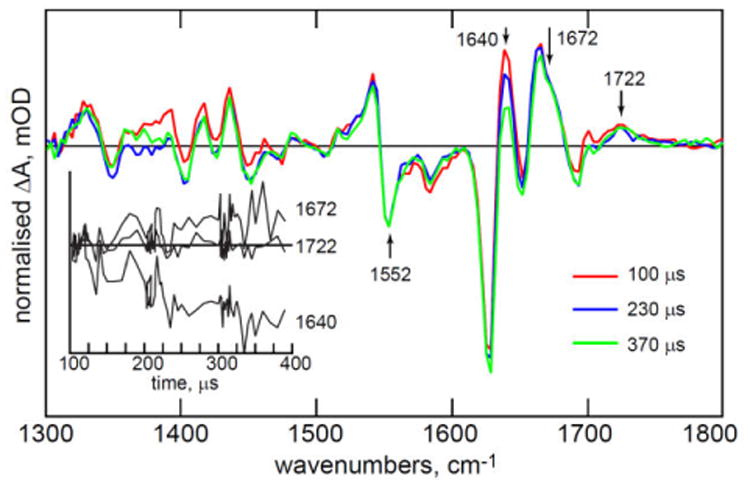

The comparison of TRIR and FTIR data in Fig. 2B pointed to continued spectral evolution on a longer (hundreds of microseconds) timescale. Such a long time constant cannot be determined accurately using kHz repetition rate apparatus, because the sample must be rastered and flowed (see on-line methods) and so necessarily replaced on this slow timescale. However, such sample replacement will affect all modes in the same way, so by normalising TRIR spectra to a characteristic chromophore mode which remains constant after A390 formation, the slow evolution can be visualised. The result is shown in Fig. 5 where data beyond 100 μs were normalised to the adduct 1552 cm-1 bleach. There is clearly continuing evolution in protein amino acid modes on the hundreds of microsecond timescale, while the 1722 cm-1 A390 isoalloxazine C4=O mode remains, as expected, unaltered. The largest change is at 1640 cm-1, where relaxation at 100 μs was incomplete (Fig. 2B) – this probably reflects relaxation in an α-helix backbone (typically around 1650 cm-1 43). There is also a smaller but significant evolution at 1672 cm-1. Interestingly, the strong bleach seen in the steady state FTIR difference spectrum at 1645 cm-1 (Fig. 2B) is not recovered within one millisecond, which points to ongoing structural relaxation on longer timescales, consistent with the observations of Pfeiffer et al.26 The observations of a series of ever slower kinetics following decay of 3FMN is characteristic of hierarchical relaxation dynamics in the protein structure stimulated by A390 formation.

Figure 5. Long Time Apoprotein Structural Evolution.

Evolution of the 1540 cm-1 normalised TRIR spectra measured for hundreds of microseconds after adduct formation, showing continued evolution in the protein structure. Kinetics at key wavenumbers are shown as an inset. Irregular spacing of data points in the inset reflects collection of more data at early time and the multiplex nature of the TRMPS experiment.22

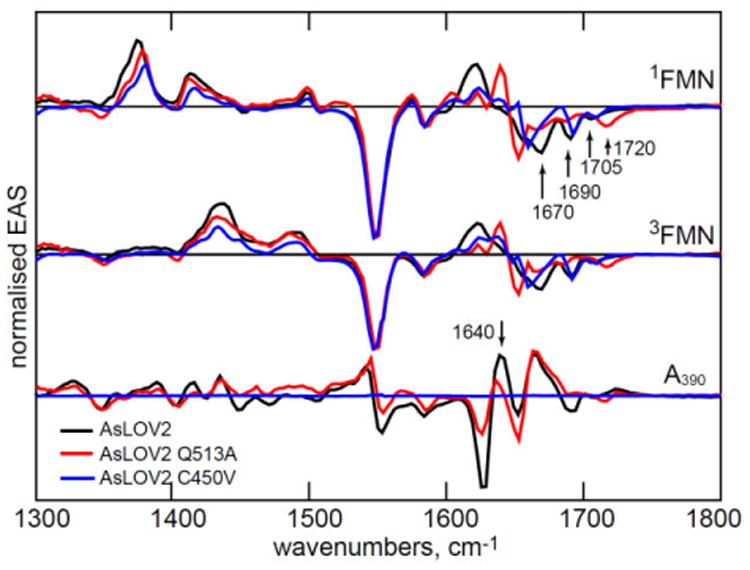

Mutants of AsLOV2

C450 is essential for adduct formation through its reaction with 3FMN 2, 13, while Q513 reorganisation is believed critical in initiating the broader structure change in the protein 19, 44. Mutation at these residues thus probes the AsLOV2 photocycle mechanism. The most significant EAS recovered from the analysis are shown in Fig. 6 and in more detail in Fig. S5.

Figure 6. EAS for C450V and Q513A.

The EAS for three key steps in the LOV photocycle for AsLOV2 and the two mutants studied.

A390 adduct formation is not possible in the C450V mutant protein, and instead the triplet lifetime is greatly extended (Table 1). Significantly, this mutation alters the TRIR spectrum of protein modes perturbed by electronic excitation. Most notably the 1670 cm-1 protein bleach (Fig 2-4) is suppressed or shifted in C450V (Fig. 6). The AsLOV2 structure (Fig. 1) shows that the cysteine sits ca 4 Å above the isoalloxazine ring, and thus does not appear to be involved directly in the H-bonding network around FMN.17 However, these TRIR data (Figs. 6, S5) show that it plays a role in the extended H-bond network. On the other hand, neither the FMN modes nor the 1690 cm-1 amino acid mode are modified in C450V (Fig. 6) and the only time dependence is the sequential appearance and decay of 3FMN (Table 1, Fig. S5).

The Q513A mutation replaces the glutamine involved in the H-bond network around the isoalloxazine chromophore with a small nonpolar non-H-bonding sidechain. In this case A390 is formed but the photocycle kinetics and associated EAS are modified. We also studied Q513L, which had a near identical effect on the TRIR spectra to Q513A, but, surprisingly, quite different 3FMN to A390 kinetics, with the reaction in Q513L being almost twice as fast as in Q513A (Fig. S6). We propose that changes in steric interactions with the larger nonpolar leucine sidechain caused cysteine 450 to move closer to the isoalloxazine ring; covalent bond formation (whatever the mechanism) is expected to be very distance dependent. Most significantly, in Q513A the 1640 cm-1 protein mode in A390 has developed to a much lesser extent than in wild type AsLOV2 within the first 100 μs (Fig. 6). Further, the slower structural evolution seen in AsLOV2 at 1640 cm-1 (Fig. 5) and assigned to changes in α-helix amide I modes, is absent in Q513A (Fig. S7).

The Q513A mutation causes major changes in the first EAS (Fig. 6). As noted by Nozaki et al.19 the FMN C4=O bleach shifts up from 1705 to 1720 cm-1 indicating a weaker H-bonding interaction between FMN carbonyl and adjacent amino acid residues, consistent with the structure (Fig. 1) which shows C4=O H-bonded to Q513 and N482. Significantly, both perturbed amino acid modes identified at 1690 and 1670 cm-1 are absent in Q513A, proving that their origin lies in the strong coupling between the isoalloxazine ring and the H-bonding network, mediated by Q513. We propose that perturbation of the H-bonding environment around the isoalloxazine ring on electronic excitation arises from a change in electron density between S0 and S1. Such a change would modify H-bond strengths, giving rise to the instantaneous perturbation observed (Figs. 2, 6). We note that a similar instantaneous change was observed in a Blue Light Using Flavin (BLUF) domain protein, in which glutamine reorganisation is also proposed to be a key step in signalling state formation.37 In that case the effect of electronic excitation has been discussed in terms of light induced structure change in the glutamine.45-50 Evidence that changes in isoalloxazine electronic structure can lead to optically induced changes in its interaction with its protein environment have also been reported in the calculations and Stark shift measurements of Kodali et al.51 A similar mechanism could operate in AsLOV2, with electronic excitation modifying the H-bond environment prior to A390 formation.

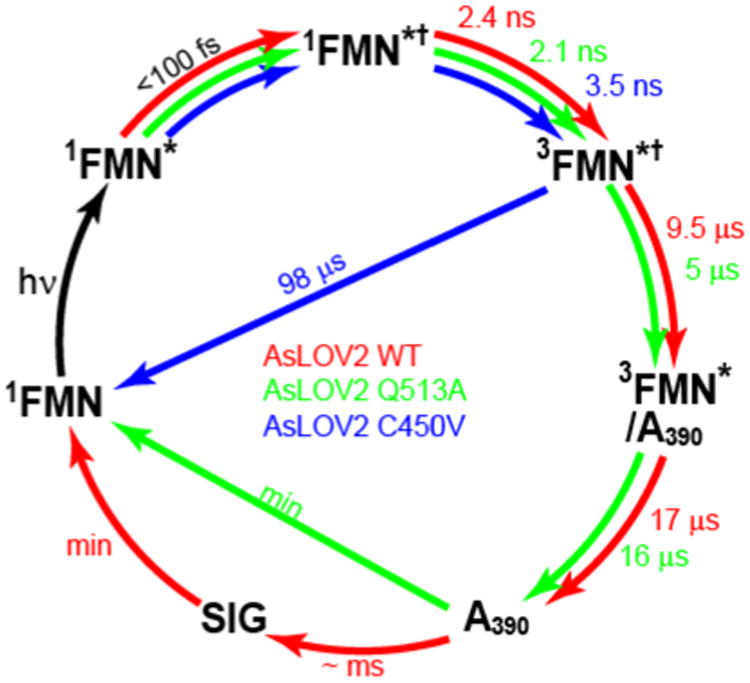

Conclusion

Structural evolution in AsLOV2 from 0.1 ps to 1 ms after absorption of a photon has been probed using high signal-to-noise IR difference spectroscopy to study the protein, its isotopologues, and two mutants. These data point to a detailed mechanism for signalling state formation in AsLOV2, summarized in Fig. 7. Electronic excitation leads directly (<1 ps) to changes in the strength of H-bonded interactions between isoalloxazine and its immediate environment. A key interaction is with Q513 but other residues are involved and affected by electronic excitation, suggesting an extensive H-bond network is perturbed by isoalloxazine excitation. The singlet excited state decays in nanoseconds to 3FMN, which undergoes reaction with an adjacent C450 residue. The evolution from the 3FMN to A390 in AsLOV2 occasions extensive perturbation to protein spectra, most likely occurring in β-sheet structures, and reveals dispersive kinetics on the 1 - 20 μs timescale, with structure change in the chromophore proceeding in parallel with the earliest changes in protein structure. Simulations suggest that important structural evolution can occur within nanoseconds of A390 formation, which is consistent with the present data, although the changes observed hereextend over a wide time-range.42 In Q513A the reaction with C450 occurs, but changes in TRIR spectra arising from perturbation to the protein structure are less extensive, and crucially do not evolve beyond 100 μs. In contrast spectral evolution in wild type AsLOV2 reveals structural changes occurring out to 1 ms (Fig. 4) and beyond.26 These slower timescale dynamics are suggested to arise from changes in secondary structure of the protein, ascribed to α-helix structures, ultimately leading to signalling state formation. Thus, the present high signal-to-noise measurements yield an accurate picture of LOV domain kinetics and connect the very earliest dynamics to steady state experiments, providing a detailed characterisation of signalling state formation in LOV domain proteins.

Figure 7. Proposed Photocycle for AsLOV2.

The earliest TRIR data show the protein modes (reported in Fig. 2-4) are a result of instantaneous perturbation (< 100 fs), consistent with changes in H-bond strength rather than protein conformation. The singlet state in that perturbed environment (1FMN*†) relaxes to a triplet, (3FMN†), which in C450V can only relax back to the ground state. In AsLOV2 the pathway to A390 is dispersive (indicated by the mixed character of the 3FMN/A390 recovered in the EAS). On a longer time scale A390 relaxes directly back to the ground state in Q513A, while wild type AsLOV2 undergoes further structural evolution on the hundreds of μs timescale leading to signalling state (SIG) formation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SRM and PJT are grateful to EPSRC (EP/G002916 and EP/N033647/1) and NSF (CHE-1223819) for funding and STFC for facility access. AL is a Bolyai Janos Research Fellow and was supported by OTKA NN113090. JNI was supported by the chemistry biology interface training grant T32GM092714. We are grateful to Prof. Ray Owens and Dr Anil Verma for assistance with protein preparation and access to the Oxford Protein production Facility, UK.

References

- 1.Losi A, Gartner W. Old Chromophores, New Photoactivation Paradigms, Trendy Applications: Flavins in Blue Light-Sensing Photoreceptors. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2010;87(3):491–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Losi A. Flavin-based blue-light photosensors: A photobiophysics update. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2007;83(6):1283–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crosson S, Rajagopal S, Moffat K. The LOV Domain Family: Photoresponsive Signaling Modules Coupled to Diverse Output Domains†. Biochemistry. 2002;42(1):2–10. doi: 10.1021/bi026978l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrou J, Crosson S. Function, structure and mechanism of bacterial photosensory LOV proteins. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2011;9(10):713–723. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glantz ST, Carpenter EJ, Melkonian M, Gardner KH, Boyden ES, Wong GKS, Chow BY. Functional and topological diversity of LOV domain photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(11):E1442–E1451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509428113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strickland D, Moffat K, Sosnick TR. Light-activated DNA binding in a designed allosteric protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(31):10709–10714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709610105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J, Natarajan M, Nashine VC, Socolich M, Vo T, Russ WP, Benkovic SJ, Ranganathan R. Surface sites for engineering allosteric control in proteins. Science. 2008;322(5900):438–442. doi: 10.1126/science.1159052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu YI, Frey D, Lungu OI, Jaehrig A, Schlichting I, Kuhlman B, Hahn KM. A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature. 2009;461(7260):104–U111. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moeglich A, Moffat K. Engineered photoreceptors as novel optogenetic tools. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. 2010;9(10):1286–1300. doi: 10.1039/c0pp00167h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt D, Cho YK. Natural photoreceptors and their application to synthetic biology. Trends in Biotechnology. 2015;33(2):80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raffelberg S, Mansurova M, Gaertner W, Losi A. Modulation of the Photocycle of a LOV Domain Photoreceptor by the Hydrogen-Bonding Network. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133(14):5346–5356. doi: 10.1021/ja1097379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Losi A, Gartner W. The Evolution of Flavin-Binding Photoreceptors: An Ancient Chromophore Serving Trendy Blue-Light Sensors. In: Merchant SS, editor. Annual Review of Plant Biology, Vol 63. Vol. 63. 2012. pp. 49–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swartz TE, Corchnoy SB, Christie JM, Lewis JW, Szundi I, Briggs WR, Bogomolni RA. The photocycle of a flavin-binding domain of the blue light photoreceptor phototropin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(39):36493–36500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennis JTM, Crosson S, Gauden M, van Stokkum IHM, Moffat K, van Grondelle R. Primary reactions of the LOV2 domain of phototropin, a plant blue-light photoreceptor. Biochemistry. 2003;42(12):3385–3392. doi: 10.1021/bi034022k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zayner JP, Sosnick TR. Factors That Control the Chemistry of the LOV Domain Photocycle. Plos One. 2014;9(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salomon M, Eisenreich W, Durr H, Schleicher E, Knieb E, Massey V, Rudiger W, Muller F, Bacher A, Richter G. An optomechanical transducer in the blue light receptor phototropin from Avena sativa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(22):12357–12361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221455298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halavaty AS, Moffat K. N- and C-Terminal Flanking Regions Modulate Light-Induced Signal Transduction in the LOV2 Domain of the Blue Light Sensor Phototropin 1 from Avena sativa†,‡. Biochemistry. 2007;46(49):14001–14009. doi: 10.1021/bi701543e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaidya AT, Chen CH, Dunlap JC, Loros JJ, Crane BR. Structure of a Light-Activated LOV Protein Dimer That Regulates Transcription. Science Signaling. 2011;4(184) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nozaki D, Iwata T, Ishikawa T, Todo T, Tokutomi S, Kandori H. Role of Gln1029 in the photoactivation processes of the LOV2 domain in Adiantum phytochrome3. Biochemistry. 2004;43(26):8373–8379. doi: 10.1021/bi0494727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harper SM, Christie JM, Gardner KH. Disruption of the LOV-J alpha helix interaction activates phototropin kinase activity. Biochemistry. 2004;43(51):16184–16192. doi: 10.1021/bi048092i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harper SM, Neil LC, Gardner KH. Structural basis of a phototropin light switch. Science. 2003;301(5639):1541–1544. doi: 10.1126/science.1086810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greetham GM, Sole D, Clark IP, Parker AW, Pollard MR, Towrie M. Time-resolved multiple probe spectroscopy. Review of Scientific Instruments. 2012;83(10) doi: 10.1063/1.4758999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwata T, Nozaki D, Sato Y, Sato K, Nishina Y, Shiga K, Tokutomi S, Kandori H. Identification of the CO Stretching Vibrations of FMN and Peptide Backbone by 13C-Labeling of the LOV2 Domain of Adiantum Phytochrome3. Biochemistry. 2006;45(51):15384–15391. doi: 10.1021/bi061837v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato Y, Iwata T, Tokutomi S, Kandori H. Reactive cysteine is protonated in the triplet excited state of the LOV2 domain in Adiantum phytochrome3. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127(4):1088–1089. doi: 10.1021/ja0436897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kottke T, Heberle J, Hehn D, Dick B, Hegemann P. Phot-LOV1: Photocycle of a blue-light receptor domain from the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biophysical Journal. 2003;84(2):1192–1201. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74933-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfeifer A, Majerus T, Zikihara K, Matsuoka D, Tokutomi S, Heberle J, Kottke T. Time-Resolved Fourier Transform Infrared Study on Photoadduct Formation and Secondary Structural Changes within the Phototropin LOV Domain. Biophysical Journal. 2009;96(4):1462–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexandre MTA, Domratcheva T, Bonetti C, van Wilderen LJGW, van Grondelle R, Groot ML, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JTM. Primary Reactions of the LOV2 Domain of Phototropin Studied with Ultrafast Mid-infrared Spectroscopy and Quantum Chemistry. Biophysical Journal. 2009;97(1):227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kutta RJ, Magerl K, Kensy U, Dick B. A search for radical intermediates in the photocycle of LOV domains. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. 2015;14(2):288–299. doi: 10.1039/c4pp00155a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konold PE, Mathes T, Weiβenborn J, Groot ML, Hegemann P, Kennis JTM. Unfolding of the C-Terminal Jα Helix in the LOV2 Photoreceptor Domain Observed by Time-Resolved Vibrational Spectroscopy. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2016:3472–3476. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b01484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tishler M, Pfister K, Babson RD, Ladenburg K, Fleming AJ. The Reaction Between Ortho-Aminoazo Compounds and Barbituric Acid - A New Synthesis Of Riboflavin. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1947;69(6):1487–1492. doi: 10.1021/ja01198a068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Illarionov B, Fischer M, Lee CY, Bacher A, Eisenreich W. Rapid preparation of isotopolog libraries by in vivo transformation of C-13-glucose. Studies on 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine, a biosynthetic precursor of vitamin B-2. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2004;69(17):5588–5594. doi: 10.1021/jo0493222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathes T, Vogl C, Stolz J, Hegemann P. In Vivo Generation of Flavoproteins with Modified Cofactors. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2009;385(5):1511–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snellenburg JJ, Laptenok SP, Seger R, Mullen KM, van Stokkum IHM. Glotaran: A Java-Based Graphical User Interface for the R Package TIMP. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012;49(3):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haigney A, Lukacs A, Brust R, Zhao RK, Towrie M, Greetham GM, Clark I, Illarionov B, Bacher A, Kim RR, Fischer M, Meech SR, Tonge PJ. Vibrational Assignment of the Ultrafast Infrared Spectrum of the Photoactivatable Flavoprotein AppA. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2012;116(35):10722–10729. doi: 10.1021/jp305220m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kondo M, Nappa J, Ronayne KL, Stelling AL, Tonge PJ, Meech SR. Ultrafast vibrational spectroscopy of the flavin chromophore. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2006;110(41):20107–20110. doi: 10.1021/jp0650735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitagawa T, Nishina Y, Kyogoku Y, Yamano T, Ohishi N, Takaisuzuki A, Yagi K. Resonance Raman-Spectra of Carbon-13-Labeled and Nitrogen-15-Labeled Riboflavin Bound To Egg-White Flavoprotein. Biochemistry. 1979;18(9):1804–1808. doi: 10.1021/bi00576a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lukacs A, Haigney A, Brust R, Zhao RK, Stelling AL, Clark IP, Towrie M, Greetham GM, Meech SR, Tonge PJ. Photoexcitation of the Blue Light Using FAD Photoreceptor AppA Results in Ultrafast Changes to the Protein Matrix. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133(42):16893–16900. doi: 10.1021/ja2060098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raffelberg S, Mansurova M, Gärtner W, Losi A. Modulation of the Photocycle of a LOV Domain Photoreceptor by the Hydrogen-Bonding Network. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133(14):5346–5356. doi: 10.1021/ja1097379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schleicher E, Kowalczyk RM, Kay CWM, Hegemann P, Bacher A, Fischer M, Bittl R, Richter G, Weber S. On the reaction mechanism of adduct formation in LOV domains of the plant blue-light receptor phototropin. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126(35):11067–11076. doi: 10.1021/ja049553q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lukacs A, Zhao RK, Haigney A, Brust R, Greetham GM, Towrie M, Tonge PJ, Meech SR. Excited State Structure and Dynamics of the Neutral and Anionic Flavin Radical Revealed by Ultrafast Transient Mid-IR to Visible Spectroscopy. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2012;116(20):5810–5818. doi: 10.1021/jp2116559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osvath S, Sabelko JJ, Gruebele M. Tuning the heterogeneous early folding dynamics of phosphoglycerate kinase. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2003;333(1):187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peter E, Dick B, Baeurle SA. Mechanism of signal transduction of the LOV2-J alpha photosensor from Avena sativa. Nature Communications. 2010;1 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barth A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Bioenergetics. 2007;1767(9):1073–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nash AI, Ko WH, Harper SM, Gardner KH. A Conserved Glutamine Plays a Central Role in LOV Domain Signal Transmission and Its Duration. Biochemistry. 2008;47(52):13842–13849. doi: 10.1021/bi801430e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stelling AL, Ronayne KL, Nappa J, Tonge PJ, Meech SR. Ultrafast structural dynamics in BLUF domains: Transient infrared spectroscopy of AppA and its mutants. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129(50):15556–15564. doi: 10.1021/ja074074n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gil AA, Haigney A, Laptenok SP, Brust R, Lukacs A, Iuliano JN, Jeng J, Melief EH, Zhao RK, Yoon E, Clark IP, Towrie M, Greetham GM, Ng A, Truglio JJ, French JB, Meech SR, Tonge PJ. Mechanism of the AppA(BLUF) Photocycle Probed by Site-Specific Incorporation of Fluorotyrosine Residues: Effect of the Y21 pK(a) on the Forward and Reverse Ground-State Reactions. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2016;138(3):926–935. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Domratcheva T, Hartmann E, Schlichting I, Kottke T. Evidence for Tautomerisation of Glutamine in BLUF Blue Light Receptors by Vibrational Spectroscopy and Computational Chemistry. Scientific Reports. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep22669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Domratcheva T, Grigorenko BL, Schlichting I, Nemukhin AV. Molecular models predict light-induced glutamine tautomerization in BLUF photoreceptors. Biophysical Journal. 2008;94(10):3872–3879. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.124172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anderson S, Dragnea V, Masuda S, Ybe J, Moffat K, Bauer C. Structure of a novel photoreceptor, the BLUF domain of AppA from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 2005;44(22):7998–8005. doi: 10.1021/bi0502691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Unno M, Masuda S, Ono TA, Yamauchi S. Orientation of a key glutamine residue in the BLUF domain from AppA revealed by mutagenesis, spectroscopy, and quantum chemical calculations. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128(17):5638–5639. doi: 10.1021/ja060633z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kodali G, Siddiqui SU, Stanley RJ. Charge Redistribution in Oxidized and Semiquinone E. coli DNA Photolyase upon Photoexcitation: Stark Spectroscopy Reveals a Rationale for the Position of Trp382. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131(13):4795–4807. doi: 10.1021/ja809214r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.