Abstract

Background

Anaplasma and Ehrlichia are emerging tick-borne pathogens that cause anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis in humans and other animals worldwide. Infections caused by these pathogens are deadly if left untreated. There has been relatively no systematic survey of these pathogens among ticks in South Africa, thus necessitating this study. The presence of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species were demonstrated by PCR in ticks collected from domestic ruminants at some selected communities in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. The ticks were identified by morphological characteristics and thereafter processed to extract bacterial DNA, which was analyzed for the presence of genetic materials of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia.

Results

Three genera of ticks comprising five species were identified. The screening yielded 16 positive genetic materials that were phylogenetically related to Ehrlichia sequences obtained from GenBank, while no positive result was obtained for Anaplasma. The obtained Ehrlichia sequences were closely related to E. chaffeensis, E. canis, E. muris and the incompletely described Ehrlichia sp. UFMG-EV and Ehrlichia sp. UFMT.

Conclusion

The findings showed that ticks in the studied areas were infected with Ehrlichia spp. and that the possibility of transmission to humans who might be tick infested is high.

Keywords: Anaplasmosis, Ehrlichiosis, South Africa, Tick-borne

Background

Ticks are well-known, excellent vectors for a variety of microorganisms, many of which are agents of emerging tick-borne zoonotic diseases [1]. Besides mosquitoes, ticks are the second-most notorious vector of human diseases; with more than 800 species of these obligate hematophagous parasites known to infest humans and animals globally [2]. The need to ingest a blood meal in order to molt to their next developmental stage makes ticks an excellent disease vector in both humans and animals.

Numerous bacterial pathogens of vertebrates, including Anaplasma spp. and Ehrlichia spp., are transmitted by ticks, and both genera contain obligate intracellular Gram-negative parasites, which are found in membrane-bound structures or vacuoles within the cytoplasm of the host cells [3–6]. There are four pathogens of ruminants in the genus Anaplasma: A. marginale, A. centrale, A. bovis and A. ovis; and in addition, there is A. phagocytophilum, which infects a variety of hosts, including humans and other animals, and A. platys, which infects dogs [7].

The genus Ehrlichia consists of E. chaffeensis, E. canis, E. ewingii, E. muris and E. ruminantium, all of which are capable of causing infections in both humans and domestic animals, consequently resulting in huge economic losses globally [7–11]. Ehrlichia muris is thought to be zoonotic and infects monocytes in rodents, whereas E. ruminantium is the etiologic agent of heartwater in ruminants and is not believed to be zoonotic. However, several people in South Africa have reportedly been infected, as it has been detected in the blood of HIV-infected patients [7].

Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are severe, feverish tick-borne illnesses arising from infections attributed to many species of the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma of the family Anaplasmataceae. In the United States, human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis is regarded as one of the most prevalent and deadly tick-borne diseases [5] and they are beginning to emerge in other parts of the world. The intricate relationship between animal reservoirs, tick vectors and humans could result in increased frequency in the diagnoses of ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis as human infections. Human ehrlichiosis is an emerging zoonotic infection that causes disease symptoms ranging from a mild feverish illness to an acute disease characterized by multiorgan system failure, while human granulocytotropic anaplasmosis (HGA) caused by A. phagocytophilum is characterized by an acute febrile illness [12, 13].

In South Africa, there is little or no information on the prevalence of tick-borne diseases among the populace, as studies in this regard are scarce. Because of the semi-arid nature of its vegetation, South Africa is known for animal rearing. Ticks are predominantly found in areas where the density of wild animals and birds is high. South Africa has a very high diversity of wild animals in many game reserves that share boundaries with rural communities. Virtually every rural community keeps domestic animals within their homesteads; and these animals, like their wild counterparts, are often infested with various tick species, which could harbour a variety of tick-borne pathogens. Tick-borne diseases most often present as fever and could easily be misdiagnosed by clinicians. There are numerous reports of travelers who have returned home from South Africa feeling sick with fever and were later diagnosed with tick-borne illnesses [14, 15].

The risk of tick-borne diseases is an important concern for many professionals, including farmers, forestry workers, military personnel and others who regularly engage in outdoor work; likewise, tourists who visit tick-infested areas and woodlands are also at risk [5, 16]. The Eastern Cape of South Africa is predominantly rural; containing many communities whose primary means of livelihood is animal rearing. These animals are kept near human dwellings and freely range within and between communities. Freely roaming animals in communities has human health implications, as zoonotic pathogens in infected animals can be easily transmitted to humans: A single bite from an infected tick could result in disease transmission. Data on the prevalence of any emerging pathogens are necessary for tracking their spread and possibly controlling their known vectors. The main objective of this study was to genetically profile the presence of Anaplasma spp. and Ehrlichia spp., which are the two pathogenic genera in the family Anaplasmataceae in ticks samples collected from domesticated animals that range freely within human dwellings in the Chris Hani and Amatole District Municipalities in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa.

Methods

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Fort Hare Ethics Committee before the commencement of the study, while permission was obtained from farmers to collect ticks from their animals with the help of veterinary personnel and animal health technicians in charge of treating the animals.

Sample collection

The collection of ticks was performed between March and June 2016 from domesticated ruminants (cattle, sheep and goats) and horses from Cofimvaba, with the geographical coordinates 32° 0′ 9″S 27° 34′ 50″E; Chemizile in the Chris Hani District Municipality, with the coordinates 32° 10′ 0″S 26° 49′ 0″E; and Alice in the Amatole District Municipality, with the coordinates 32° 47′S 26° 50′E. These study sites were chosen because they are primarily known for animal husbandry within Eastern Cape Province. Tick collection was arbitrarily conducted based on the availability of domestic animals, but efforts were made to obtain a widespread representative sample within the different animal species included in the study. Tick collection was carried out with the help of animal health technicians from the South African Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF). University of Fort Hare Animal Ethics Committee regulations were strictly adhered to in the handling of the animals.

Ticks were collected into 50 mL Nalgene tubes containing 70% ethanol and transported to the Applied and Environmental Microbiology Research Group in the Microbiology Department at the University of Fort Hare. During sampling, care was taken to ensure that ticks collected from each animal were placed in separate tubes and properly labelled.

Tick identification and bacterial DNA extraction

Following identification to species based on morphological criteria previously outlined by [17], the ticks were washed in sterile distilled water and chopped with a sterile blade in a Petri dish containing lysis buffer with proteinase K. Individual engorged ticks were extracted separately, while pools of 10 or more non-engorged ticks were extracted together according to the animal, place of collection and tick species delineation. Each chopped tick or pool was mechanically triturated in 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 100 μg proteinase K per mL, and 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate lysing buffer, incubated at 60 °C for 1 h, and then centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min;. The supernatants were then collected in a clean 2-mL microcentrifuge tube, after which DNA extraction was performed using the Zymo Research Quick-DNA Universal Kit (Zymo Research, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Detection of Anaplasma spp. and Ehrlichia spp. in ticks

The presence of Anaplasma spp. and Ehrlichia spp. in the ticks were detected following the methods previously described by Sun et al. [18]. Briefly, we targeted the 16S RNA of Anaplasma spp. and the genus-specific disulfide bond formation protein (dsbA) gene of Ehrlichia spp. with the following primer pairs: ANA F 5′-GCAAGTCGAACGGATTATTC-3′ and ANAR 5′-TTCCGTTAAGAAGGATCTAATCTCC-3′ to generate a 932 bp PCR fragment, and EHL dsb-330 5′-GATGATGTCTGAAGATATGAAACAAAT-3′ and EHL dsb-728 5′-CTGCTCGTCTATTTTACTTCTTAAAGT-3′ to generate 409 bp fragments of Anaplasma 16S RNA and Ehrlichia dsbA genes, respectively. PCRs were performed in a 25-μL reaction mixture containing 12.5 μL of the master mix, 1 μL of 10 pMol for each of the forward and reverse primers, 5.5 μL of RNase nuclease-free water, and 5 μL of DNA template. The cycling conditions were as follows: an initial heating block at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 93 °C for 30 s, then annealing at 50 °C for Anaplasma and 47 °C for Ehrlichia with an elongation at 72 °C for 1 min and a final elongation at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR amplification was verified in 1% gel electrophoreses stained with ethidium bromide, electrophoresed at 120 volts for 45 mins in 0.5X TBE buffer, visualized under a UV transilluminator and then photographed.

Sequencing, sequence editing, and compilation

Positive amplicons were sequenced on both strands, and generated sequences were edited with Geneious bioinformatics tools (Biomatters Ltd, Auckland, NZ) and analyzed phylogenetically.

Automated population-based sequencing was performed on both strands of bacterial DNA with the forward and reverse primers that were used to amplify the target region of the dsbA of Ehrlichia spp. was detected using the dideoxynucleotide chain termination approach on an ABI Prism DNA genetic analyzer (ABI Prism 310, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) while no sample was positive for Anaplasma spp. Forward and reverse nucleotide sequences were assembled and edited with the Geneious programme in the R9 software, version 9.1.5 [19].

Blast search and phylogenetic analysis

The sequences data obtained after editing were analyzed for homologies with other sequences in GenBank with the BLAST program (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), with the parameters set on highly similar sequences and Ehrlichiaceae chosen as the organism option. Sequences with a percentage similarity above 95% were downloaded for phylogenetic tree analysis. Sequences generated in this study were aligned and compared with these GenBank reference sequences representing the different species of the Ehrlichia-partial dsbA gene. The sequences were then manually edited with the Geneious 9.1.5 align/assemble software, and gaps were removed from the final alignments. Neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed using the tree builder. In order to probe the statistical robustness of the tree, bootstrapping was performed with 1000 replicates.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

Representative sequences obtained from this study have been deposited in the GenBank under the following accession numbers: KX922864 – KX922879.

Results

A total of 760 adult hard ticks were collected in this study. These ticks belonged to three genera, Rhipicephalus, Amblyomma and Hyalomma, comprising five species. The most-to-least collected species were Rhipicephalus eversti eversti (360 adults), followed by R. sanguineus s.l. (180 adults), R. appendiculatus (120 adults), Amblyomma hebraeum (50 adults) and Hyalomma marginatum rufipes (50 adults). Similarity in the diversity of collected ticks was detected at each site except from the site with horses, where no tick was recovered. The species, number and prevalence of Ehrlichia in hard ticks at each collection site are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Proportion and distribution of collected tick species and the prevalence of Ehrlichia spp.

| Animal/Location | Tick species | Developmental stage | Number | Positive for Ehrlichia spp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | R. eversti eversti | Adult | 160 | n/d |

| R. sanguineus s.l. | Adult | 70 | 3 (E2, E12, E15) | |

| R. appendiculatus | Adult | 50 | 2 (E1, E8) | |

| Rhipicephalus spp. | Nymph | 0 | n/a | |

| A. hebraeum | Adult | 25 | 3 (E10, E7, E13) | |

| H. marginatum rufipes | Adult | 8 | n/d | |

| Sheep | R. eversti eversti | Adult | 140 | 1 (E11) |

| R. sanguineus s.l. | Adult | 50 | 2 (E5, E14) | |

| R. appendiculatus | Adult | 30 | 1 (E17) | |

| Rhipicephalus spp. | Nymph | 0 | n/a | |

| A. hebraeum | Adult | 15 | 4 (E3, E4, E16, E9) | |

| H. marginatum rufipes | Adult | 12 | n/d | |

| Goats | R. eversti eversti | Adult | 60 | n/d |

| R. sanguineus s.l. | Adult | 60 | n/d | |

| R. appendiculatus | Adult | 40 | n/d | |

| Rhipicephalus spp. | Nymph | 0 | n/a | |

| A. hebraeum | Adult | 10 | n/d | |

| H. marginatum rufipes | Adult | 30 | n/d | |

| Horse | R. eversti eversti | Adult | 0 | n/a |

| R. sanguineus s.l. | Adult | 0 | n/a | |

| R. appendiculatus | Adult | 0 | n/a | |

| Rhipicephalus spp. | Nymph | 0 | n/a | |

| A. hebraeum | Adult | 0 | n/a | |

| H. marginatum rufipes | Adult | 0 | n/a |

Key: n/a not available, n/d not detected

Molecular detection of Ehrlichia spp. in ticks

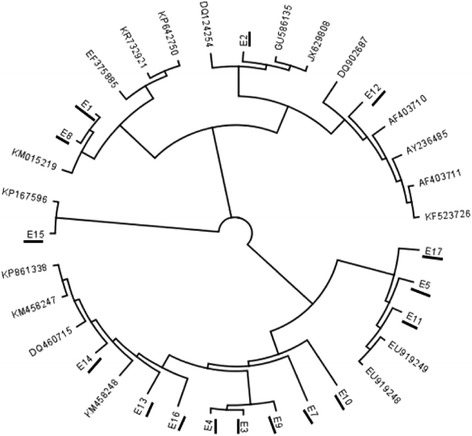

A total of 16 positive samples were obtained from the 760 ticks analyzed for the presence of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia genetic materials (DNA) using primer pairs specific to the thio-oxidoreductase protein gene (dsbA) of the Ehrlichia genus and 16S RNA gene-specific primers of Anaplasma. The identified positive samples were all of Ehrlichia; none were positive for Anaplasma. The samples identified from the respective tick species analyzed are shown in Table 1. A homology search for the obtained sequences from PCR data showed that they had a high sequence similarity of above 95% with homologous dsbA of other Ehrlichia sequences in GenBank. Sequence E8 had a 98% similarity to Ehrlichia sp. UFMG-EV (JX629808) and Ehrlichia sp. UFMT (KT970783), while E7 was 96% similar to E. canis (KU534872); likewise, E15 was 98% similar to E. canis (DQ124254, KR732921). Other sequences that demonstrated a high degree of similarity (98%) with E. canis sequences were E9, E12, E14, E1 and E2 (KU534892). E11 was 100% similar to E. canis (KR732921, KP167596, and KU534872). The other remaining sequences (E13, E4, E16, E7, E10, E3) were more than 97% similar to E. chaffeensis (KM458248), while sequences E17, E5 and E11 were 99% homologous to E. muris (E919249, EU919248). Phylogenetic analysis of the derived sequences was performed with these Ehrlichia dsbA GenBank reference sequences after an alignment was made via Geneious’ alignment editor and tree builder, both included in the software Biomatters Ltd [19]. In the constructed phylogenetic tree, the sequences obtained in this study clustered with reference sequences of Ehrlichia spp. obtained from GenBank homology search using BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Sequences E5, E11 and E17 clustered with E. muris with accession numbers EU919249 and EU919248, while sequences E10, E7, E9, E3 and E4 clustered close by; E16, E13 and E14 clustered with E. chaffeensis (KMN458248). Sequence E15 clustered phylogenetically with E. canis (KP167596); likewise, E2 and E12 clustered with DQ124254 and DQ902687, respectively. E1 and E8 sequences clustered with Ehrlichia sp. UFMG-EV minasensis (KM015219), as shown in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationship of various Ehrlichia spp. based on the nucleotide sequences of the genus-specific disulfide bond formation protein (dsbA) gene of Ehrlichia spp. The underlined are the Ehrlichia spp. sequences detected in this study. All the detected sequences in this study clustered phylogenetically with reference Ehrlichia spp. dsbA gene sequences obtained from the GenBank. The tree was drawn with Geneious version 9.1.5, created by Biomatters and available from http://www.geneious.com, Kearse et al., [19]

Discussion

Members of the genus Ehrlichia, the causative agent of human monocytotrophic ehrlichiosis (HME), are becoming recognized as emerging tick-borne pathogens worldwide. Ehrlichia spp. are naturally transmitted by Ixodidae and are maintained between the ticks and wild or domestic animal reservoir hosts [20–22]. A total of 760 ticks were collected and analysed for the presence of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia spp. Anaplasma spp. were not identified, while genetic material from 16 Ehrlichia spp. were detected. Three of the genetic materials clustered with E. canis, while eight were phylogenetically related to E. chaffeensis. Of the remaining five genetic materials, three clustered phylogenetically with E. muris, while two were closely related to the incompletely described Ehrlichia sp. UFMG-EV minasensis.

Ehrlichia canis can cause illness in dogs and other canids, which are thought to be the reservoir hosts of the pathogen. Human infections from E. canis have been reported, but the incidence is quite low. In Venezuela, chronic, asymptomatic infections by E. canis in human patients have been described, in addition to six clinical cases of ehrlichiosis [8, 23]. All of the patients with clinical cases had a fever, headache, and generalized body pain. In some patients, arthralgia, diarrhea and vomiting, malaise, nausea accompanied by body rash, and abdominal pain also occurred, while leukopenia was observed in one patient and anemia in another [8, 23]. The six patients were young and apparently healthy, and the E. canis strains obtained from them were indistinguishable from those found in dogs [8, 23]. Ehrlichia canis nucleic acids also have been detected from stored human blood samples in the U.S. Bouza-Mora et al. [24] recently reported the detection of a novel E. canis in blood samples collected from blood donors in Costa Rica. Although E. canis occurs worldwide, its presence and density varies with the geographic distribution of its tick vectors, like any other tick-borne bacterial pathogen. The presence of a novel Ehrlichia genotype suspected to be E. canis in dogs in South Africa has been reported by Allsopp and Allsopp [25]. In a study carried out by Williams et al. [26] on dogs and wild canids in Zambia, there was no reported detection of E. canis among the study population, while Matjila et al. [27] reported a 3% prevalence of E. canis in blood samples collected over a period of 7 years from dogs in South Africa. The natural tick host of E. canis is the brown dog tick, R. sanguienius s.l, which is widely distributed in South Africa. Here we report the genetic detection of E. canis from ticks collected from domesticated ruminants. We detected the genetic material of E. canis in four samples from R. sanguineus s.l. collected from cattle and sheep. Dogs are naturally infected with this pathogen, but its presence in ticks collected from cattle and sheep should not be unusual since dogs are companion pets of herdsmen. Moreover, it is possible for an infected questing tick of any age to attach itself to any available animal host; hence, finding E. canis in cattle and sheep is not unusual. One study of E. canis in South Africa reported a prevalence of 1% [27]; another study by Pretorius and Kelly [28] was based on the seroprevalence of Ehrlichia spp., which in most cases is not definitive due to lack of specificity of antibody reactions in distinguishing infections caused by Ehrlichia spp. The reports on E. canis detection in ticks collected from ruminants across the globe also is limited except for Zhang et al. [29], who reported the detection of E. canis in the blood of ruminants collected on five Caribbean Islands. On the African continent, Ndip et al. [13] reported a 16.3% prevalence of E. canis in dogs studied in Cameroon.

Ehrlichia chaffeensis is an emerging tick-borne pathogen known to cause illness in humans [22]. According to the Centers for Disease Control [30], ehrlichiosis was first documented as a disease in the U.S. in the late 1980s but became a reportable disease only in 1999. Since then, the number of ehrlichiosis cases due to E. chaffeensis has increased steadily both in the U.S. and across the globe [7]. Ehrlichia chaffeensis is responsible for the disease known as human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME). White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) are the major reservoir host of E. chaffeensis in the U.S., although it has also been detected across the globe in other deer species, such as the spotted deer (Cervus nippon) in Japan and Korea and the marsh deer in Brazil, as well as in numerous other wild and domesticated animals [20, 21, 31]. Also, E. chaffeensis genetic materials have been detected by PCR in coyotes in the US and wild lemurs while antibodies to the bacteria have been reported in opossums, raccoons, rabbits and foxes [32–38].

Ehrlichiosis is most commonly detected in the Southeastern and South Central United States, an area corresponding to the natural habitat of Amblyomma americanum, the known vector of E. chaffeensis [30, 39–42]. Data on the true prevalence of E. chaffeensis in South Africa is limited. On the African continent, ehrlichiosis in humans caused by E. chaffeensis has been reported in Cameroonian patients by Ndip et al. [7], with a prevalence of 10% among 118 patients. Amblyomma americanum, the tick vector of E. chaffeensis, is found only in the U.S.; however, reports abound in the literature of the detection of E. chaffeensis DNA in other tick species, such as Dermacentor variabilis, Ixodes pacificus, A. testudinarium, Haemaphysalis longicornis and H. yeni [7, 43–47], suggesting that other vector agents do exist. Here, we report the detection of genetic materials from ticks that clustered phylogenetically close to E. chaffeensis sequences obtained from the GenBank in a phylogenetic tree. The genetic materials were detected in A. hebraeum collected from both cattle and sheep in two communities within the study areas, thus supporting reports that other ticks may be vectoring this pathogen across the globe.

In 2009, an E. muris-like (EML) pathogen was detected in four patients in Minnesota and Wisconsin in the U.S., thus implicating this bacterium, which is commonly found in rodents, in human infections [48–50]. Ehrlichia muris is capable of causing infections in humans characterized by fever, headache, nausea, vomiting and fatigue [51]. DNA from this bacterial pathogen also has been detected in the blood of deer and small rodents, with the latter having been suggested as the probable reservoir host [51] for I. persulcatus, which feeds on them as its tick vector [30]. The first description of E. muris was in rodents in Japan [49–52], where it also was associated with human infection first. Ravyn et al. [53] have also reported the identification of E. muris from I. persulcatus ticks in Russia, while Spitalská et al. [54] detected E. muris in I. ricinus in Slovakia, thus suggesting the possibility of the pathogen’s maintenance via rodent-feeding ticks. Three of the Ehrlichia-positive samples detected in this study contained genetic materials that clustered phylogenetically with E. muris, which to the best of our knowledge is being reported for the first time in South Africa. Also detected in this study were two sequences that clustered with the Ehrlichia sp. UFMG EV minasensis, a new genotype phylogenetically close to E. canis that was first identified in infected cattle and deer in Canada. Ehrlichia sp. UFMG EV minasensis also has been reported in R. microplus ticks and cattle in Brazil by Cabezas-Cruz et al. [10] and Carvalho et al. [11]. The pathogenic potential of this new Ehrlichia sp. is yet to be determined.

Reports on human ehrlichiosis in Africa is uncommon, as only Ndip et al. [7] have thus far characterized genetic material belonging to the bacteria in Cameroon. Another study on the seroprevalence of antibodies to Ehrlichia in blood samples collected across Africa showed that only two samples, one each from Mali and Mozambique, were positive [55]. The severity of ehrlichiosis depends on the individual immune status, as people with compromised immunity caused by HIV infection, immunosuppressive therapies or splenectomies develop more severe disease [30]. Because of the high HIV/AIDS prevalence in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, the incidence of ehrlichiosis could be high. However, a comprehensive study is yet to be conducted on this emerging disease. With a 2.3% prevalence of this emerging tick-borne pathogen, there is a good chance that human infections could be going undetected as they may be mistaken for the flu or flu-like infections. The short duration of this study poses one limitation to our findings; likewise, few sites were used and the number of ticks collected was low. Further studies are needed to redress these limitations.

Conclusion

Infectious diseases do not respect international boundaries and there are very few systematic studies of tick-borne pathogens in ticks collected in South Africa. The prevalence of Ehrlichia spp. among ticks collected in this study was low and Anaplasma spp. was not detected in any samples tested. For a better understanding of the true situation, long-term surveillance of the prevalence of Ehrlichia and other tick-borne bacterial pathogens in South Africa that incorporates different climatic conditions and wider geographic areas is necessary in order to accurately determine the disease transmission risks associated with emerging tick-borne bacterial pathogens and the distribution of their vectors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the animal health technicians of the Chris Hani District Municipality who helped with tick collection, as well as the farmers who allowed us to collect ticks from their animals.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Department for International Development (DFiD) under the Climate Impact Research Capacity and Leadership Enhancement (CIRCLE) program and the South African Medical Research Council. Dr. BC Iweriebor is a recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship.

Availability of data and materials

KX922864 –KX922879.

Authors’ contributions

BCI designed and conducted the research and wrote the manuscript; AI helped in sample collection and laboratory protocols; AAA assisted in laboratory protocols and analyses; EJM read and edited the manuscript; AIO proofread the manuscript; and LCO edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for Publication

Not Applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Fort Hare Ethics Committee (REC-270710-028-RA Level 01. Consent to participate was granted by farmers whose farms were sampled.

Abbreviations

- CME

Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis

- HME

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis

Contributor Information

Benson C. Iweriebor, Email: benvida2004@yahoo.com

Elia J. Mmbaga, Email: eliajelia@yahoo.co.uk

Abiodun Adegborioye, Email: 201502174@ufh.ac.za.

Aboi Igwaran, Email: 201508688@ufh.ac.za.

Larry C. Obi, Email: lobi@ufh.ac.za

Anthony I. Okoh, Email: aokoh@ufh.ac.za

References

- 1.Mitchell EA, Williamson PC, Billingsley PM, Seals JP, Ferguson EE, Allen MS. Frequency and Distribution of Rickettsiae, Borreliae, and Ehrlichiae Detected in Human-Parasitizing Ticks, Texas, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(2). www.cdc.gov/eid. Accessed 17 Oct 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Parola P, Raoult D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:897–928. doi: 10.1086/319347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson BE, Dawson JE, Jones DC, Wilson KH. Ehrlichia chaffeensis, a new species associated with human ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2838–42. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2838-2842.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dumler JS, Barbet AF, Bekker CP. Reorganization of genera in the families Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae in the order Rickettsiales: unification of some species of Ehrlichia with Anaplasma, Cowdria with Ehrlichia and Ehrlichia with Neorickettsia, descriptions of six new species combinations and designation of Ehrlichia equi and ‘HGE agent’ as subjective synonyms of Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51(Pt 6):2145–65. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-6-2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rymaszewska A, Grenda S. Bacteria of the genus Anaplasma – characteristics of Anaplasma and their vectors. Vet Med. 2008;53(11):573–584. [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC 2015. Geographic distribution of ticks that bite humans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assessed on 1/10/2016.

- 7.Ndip LM, Ndip RN, Esemu SN, Walker DH, McBride JW. Predominance of Ehrlichia chaffeensis in Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks from kennel-confined dogs in Limbe, Cameroon. Exp Appl Acarol. 2010;50:163. doi: 10.1007/s10493-009-9293-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez M, Bodor M, Zhang C, Xiong Q, Rikihisa Y. Human infection with Ehrlichia canis accompanied by clinical signs in Venezuela. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1078:110–7. doi: 10.1196/annals.1374.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ismail N, Bloch KC, McBride JW. Human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis. Clin Lab Med. 2010;30(1):261–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabezas-Cruz A, Zweygarth E, Vancová M, Broniszewska M, Grubhoffer L, Passos LMF, Ribeiro MFB, Alberdi P, de la Fuente J. Ehrlichia minasensis sp. nov., isolated from the tick Rhipicephalus microplus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:1426–1430. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carvalho ITS, Melo LTA, Freitas CL, Verçoza RV, Alves AS, Costa JS, Chitarra CS, Nakazato L, Dutra V, Pacheco RC, Aguiar DM. Minimum infection rate of Ehrlichia minasensis in Rhipicephalus microplus and Amblyomma sculptum ticks in Brazil. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7(5):849–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalinová Z, Cisláková L, Halánová M. Ehrlichiosis/Anaplasmosis. Klin Mikrobiol Infekc Lek. 2009;15(6):210–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ndip LM, Ndip RN, Esemu SN, Dickmu VL, Fokam EB, Walker DW, McBride JW. Ehrlichial infection in Cameroonian canines by Ehrlichia canis and Ehrlichia ewingii. Vet Microbiol. 2005;111(1–2):59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozhevnikova GM, Tokmalaev AK, Voznesensky SL, Karan LS. South African tick bite fever in a group of Russian tourists. Ter Arkh. 2014;86(11):82–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binder WD, Gupta R. African tick-bite fever in a returning traveler. J Emerg Med. 2015;48(5):562–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cisak J, Zajac V, Nojick-Fatla A, Dutkiewicz J. Risk of tick-borne diseases in various categories of employment among forestry workers in eastern Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19(3):469–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker JB, Keirans JE, Horak IG. The genus Rhipicephalus (Acari, Ixodidae) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. p. 643. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun J, Liu Q, Lu L, Ding G, Guo J, Fu G, Zhang J, Meng F, Wu H, Song X, Ren D, Li D, Guo Y, Wang J, Li G, Liu J, Lin H. Coinfection with four genera of bacteria (Borrelia, Bartonella, Anaplasma, and Ehrlichia) in Haemaphysalis longicornis and Ixodes sinensis ticks from China. Vector Borne Zoonot Dis. 2008;8:791–795. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2008.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Mentjies P, Drummond A. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mixson TR, Campbell SR, Gill JS, Ginsberg HS, Reichard MV, Schulze TL, Dasch GA. Prevalence of Ehrlichia, Borrelia, and Rickettsial agents in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) collected from nine states. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:1261–1268. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2006)43[1261:poebar]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paddock CD, Yabsley MJ. Ecological havoc, the rise of white-tailed deer, and the emergence of Amblyomma americanum-associated zoonoses in the United States. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;315:289–324. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paddock CD, Childs JE. Ehrlichia chaffeensis: a prototypical emerging pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:37–64. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.37-64.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez M, Rikihisa Y, Wen B. Ehrlichia canis-like agent isolated from a man in Venezuela: antigenic and genetic characterization. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(9):2133–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2133-2139.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouza-Mora L, Dolz G, Solórzano-Morales A, José Romero-Zuñiga J, Salazar-Sánchez L, Labruna MB, Aguia DM. Novel genotype of Ehrlichia canis detected in samples of human blood bank donors in Costa Rica. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017;8(1):36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allsopp MTEP, Allsopp BA. Novel Ehrlichia genotype detected in dogs in South Africa. J Clin Microbio. 2001;39(11):4204–4207. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.11.4204-4207.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams BM, Berentsen A, Shock BC, Teiiera M, Dunber MR, Becker MJ, Yabsle MS. Prevalence and diversity of Babesia, Hepatozoon, Ehrlichia, and Bartonella in wild and domestic carnivores from Zambia, Africa. Parasito Res. 2014;113(3):911–918. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3722-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matjila PT, Leisewitz AL, Jongejan F, Penzhorn BL. Molecular detection of tick-borne protozoal and ehrlichial infections in domestic dogs in South Africa. Vet Parasitol. 2008;155:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pretorius AM, Kelly PJ. Serological survey for antibodies reactive with Ehrlichia canis and E. chaffeensis in dogs from the Bloemfontein area, South Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1998;69(4):126–8. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v69i4.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Kelly P, Guo W, Xu C, Wei F, Jongejan L, Loftis A, Wang C. Development of a generic Ehrlichia FRET-qPCR and investigation of ehrlichioses in domestic ruminants on five Caribbean islands. Parasit Vect. 2015;8:506. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1118-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. Ehrlichiosis. CDC. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ehrlichiosis/. Accessed 22 Sept 2016.

- 31.Machado RZ, Duarte JM, Dagnone AS, Szabo MP. Detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis in Brazilian marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus) Vet Parasitol. 2006;139:262–266. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoffel RT, Johnson GC, Boughan K, Ewing SA, Stich RW. Detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis in a naturally infected elk (Cervus elaphus) from Missouri, USA JMM Case Rep, 2015 2. doi: 10.1099/jmmcr.0.000015.

- 33.Williams CV, Van Steenhouse JL, Bradley JM, Hancock SI, Hegarty BC, Breitschwerdt EB. Naturally occurring Ehrlichia chaffeensis infection in two prosimian primate species: ringtailed lemurs (Lemur catta) and ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata) Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1497–1500. doi: 10.3201/eid0812.020085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yabsley MJ, Davidson WR, Stallknecht DE, Varela AS, Swift PK, Devos JC, Jr, Dubay SA. Evidence of tickborne organisms in mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) from the western United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2005;5:351–362. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2005.5.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yabsley MJ, Norton TM, Powell MR, Davidson WR. Molecular and serologic evidence of tick-borne Ehrlichiae in three species of lemurs from St. Catherines Island, Georgia, USA. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2004;35:503–509. doi: 10.1638/03-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawahara M, Tajima T, Torii H, Yabutani M, Ishii J, Harasawa M, Isogai E, Rikihisa Y. Ehrlichia chaffeensis infection of sika deer, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1991–1993. doi: 10.3201/eid1512.081667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee M, Yu D, Yoon J, Li Y, Lee J, Park J. Natural coinfection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Anaplasma bovis in a deer in South Korea. J Vet Med Sci. 2009;71:101–103. doi: 10.1292/jvms.71.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davidson WR, Lockhart JM, Stallknecht DE, Howerth EW. Susceptibility of red and gray foxes to infection by Ehrlichia chaffeensis. J Wildl Dis. 1999;35(4):696–702. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-35.4.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaines DN, Operario DJ, Stroup S, Stromdahl E, Wright C, Gaff H, Broyhill J, Smith J, Norris DE, Henning T, Lucas A, Houpt E. Ehrlichia and spotted fever group Rickettsiae surveillance in Amblyomma americanum in Virginia through use of a novel six-plex real-time PCR assay. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14(5):307–16. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Varela-Stokes AS. Transmission of Ehrlichia chaffeensis from lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum) to white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) J Wildl Dis. 2007;43(3):376–81. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-43.3.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sayler KA, Loftis AD, Beatty SK, Boyce CL, Garrison E, Clemons B, Cunningham M, Alleman AR, Barbet AF. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in host-seeking Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) and Odocoileus virginianus (Artiodactyla: Cervidae) in Florida. J Med Entomol. 2016;53(4):949–956. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjw054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yabsley MJ. Natural history of Ehrlichia chaffeensis: vertebrate hosts and tick vectors from the United States and evidence for endemic transmission in other countries. Vet Parasitol. 2010;167(2–4):136–48. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao WC, Gao YM, Zhang PH, Zhang XT, Dai QH, Dumler JS, Fang LQ, Yang H. Identification of Ehrlichia chaffeensis by nested PCR in ticks from Southern China. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2778–2780. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.7.2778-2780.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee SO, Na DK, Kim CM, Li YH, Cho YH, Park JH, Lee JH, Eo SK, Klein TA, Chae JS. Identification and prevalence of Ehrlichia chaffeensis infection in Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks from Korea by PCR, sequencing and phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA gene. J Vet Sci. 2005;6:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim CM, Kim MS, Park MS, Park JH, Chae JS. Identification of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and A. bovis in Haemaphysalis longicornis and Ixodes persulcatus ticks from Korea. Vect Borne Zoono Dis. 2003;3:17–26. doi: 10.1089/153036603765627424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kramer VL, Randolph MP, Hui LT, Irwin WE, Gutierrez AG, Vugia DJ. Detection of the agents of human ehrlichiosis in ixodid ticks from California. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:62–65. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steiert JG, Gilfoy F. Infection rates of Amblyomma americanum and Dermacentor variabilis by Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia ewingii in southwest Missouri. Vect Borne Zoonot Dis. 2004:53–60. doi:10.1089/153036602321131841. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Hoang JDK, Schiffman EK, Davis JP, Neitzel DF, Sloan LM, Nicholson WL. Human infection with Ehrlichia muris–like pathogen, United States, 2007–2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;20(10). DOI: 10.3201/eid2110.150143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Sam RS, Telford SR, III, Goethert KH, Cunningham JA. Prevalence of Ehrlichia muris in Wisconsin deer ticks collected during the Mid 1990s. Open Microbiol. 2011;5:18–20. doi: 10.2174/1874285801105010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pritt BS, Sloan LM, Johnson DK, Munderloh UG, Paskewitz SM, McElroy KM. Emergence of a new pathogenic Ehrlichia species, Wisconsin and Minnesota. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:422–429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Telford III SR, Goethert HK. Emerging and emergent tickborne infections. Pp 344–376 in Ticks: Biology, Disease, and Control. Eds. Chappell LH, Bowman AS, Nuttall PA. Cambridge University Press. T T-b Dis.2008; 7(5): 849–852.

- 52.Kawahara M, Suto C, Rikihisa Y, Yamamoto S, Tsuboi Y. Characterization of ehrlichial organisms isolated from a wild mouse. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:89–96. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.1.89-96.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ravyn MD, Korenberg EI, Oeding JA, Kovalevskii YV, Johnson RC. Monocytic Ehrlichia in Ixodes persulcatus ticks from Perm, Russia. Lancet. 1999;353:722–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spitalská E, Boldis V, Kostanová Z, Kocianová E, Stefanidesová K. Incidence of various tick-borne microorganisms in rodents and ticks of central Slovakia. Acta Virol. 2008;52:175–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brouqui P, Le Cam C, Kelly PJ, Laurens R, Tounkara A, Sawadogo S, Velo-Marcel S. Serologic evidence for human ehrlichiosis in Africa. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10(6):695–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01719283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

KX922864 –KX922879.