Abstract

Introduction:

The prevalence of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has reached alarming proportions due to the rapidly increasing rates of this disease worldwide. Preclinical and clinical studies have revealed elevated levels of inflammatory markers in a vast number of illnesses such as T2DM, obesity, and atherothrombosis collectively called metabolic syndrome leading to adverse cardiovascular events. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors which are the enhancers of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP -1), could have anti-inflammatory potential which could help in reducing cardiovascular complications of diabetes and benefit patients suffering from the metabolic syndrome.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to analyze the effect of DPP-4 inhibitors, namely vildagliptin and saxagliptin on acute and subacute models of inflammation.

Materials and Methods:

Male Wistar rats were randomly divided into control, standard, and two treatment groups (6 animals in each group, total 24 animals). The animals received the drugs orally. The effects of vildagliptin and saxagliptin on inflammation were tested in acute (carrageenan-induced paw edema method) and subacute (grass pith and cotton pellet implantation method) models of inflammation.

Results:

Vildagliptin and saxagliptin used in the present study showed a significant anti-inflammatory activity in acute and subacute models of inflammation.

Conclusion:

The present study suggests that vildagliptin and saxagliptin have significant anti-inflammatory potential. Based on the findings of the present study and the available literature, it can be concluded that the anti-inflammatory potential of DPP-4 inhibitors could help to reduce the cardiovascular complications of Type 2 diabetes and the related cluster of metabolic disorders collectively called the metabolic syndrome.

Key words: Inflammation, saxagliptin, vildagliptin

INTRODUCTION

The world prevalence of diabetes among adults (aged 20–79 years) is estimated to be 6.4%, affecting 285 million adults in 2010, and will increase to 7.7% and affect 439 million adults by 2030. Between 2010 and 2030, there will be a 69% increase in the number of adults with diabetes in developing countries and a 20% increase in developed countries.[1]

Low-grade inflammation has been viewed as a major pathophysiological factor in insulin resistance development and evolution of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).[2] A vast number of investigations both clinical as well as preclinical have revealed an association between low-grade inflammation and a vast number of pathologies such as T2DM, obesity, and atherothrombosis collectively called metabolic syndrome, leading to adverse cardiovascular events.[3]

The receptors for the incretin, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), are expressed in a wide variety of tissues such as the endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, monocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes, raising the possibility that GLP-1 could have direct effects on atherosclerosis and inflammation. Among the various effects of GLP-1 on the cardiovascular system, one of the important effects is reduction of inflammation by reducing the levels of inflammatory mediators, decreased monocyte adhesion, reduction in the proliferation of macrophages and macrophage foam cell formation, and smooth muscle cell proliferation. In addition to this, in the cardiovascular system, incretins have also been found to enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses, inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and attenuate endothelial inflammation and dysfunction. GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide has been found to reduce oxidative stress, microvascular endothelial dysfunction, and markers of inflammation such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α).[4,5,6]

Literature points to the fact that GLP-1 receptors have a widespread distribution, and GLP-1 and its analogs have anti-inflammatory potential. Hence, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors which are the enhancers of GLP-1 could have anti-inflammatory potential. Hence, the current study was taken up to explore the anti-inflammatory potential of DPP-4 inhibitors, namely vildagliptin and saxagliptin in male Wistar rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

Twenty four adult male Wistar rats of 150–200 g body weight were obtained from the central animal house of the institution. Animals were housed under standard conditions and acclimatized to 12 h light/dark cycle 10 days prior to the day of experimentation. They were given access to food (standard rat chow pellets) and water ad libitum. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee.

Experimental setup

Rats were divided into four groups with six animals in each group. They were randomly divided into control, standard, and two treatment groups. Group I – control group received 0.5 ml of 1% gum acacia suspension, orally. Group II – standard group received oral aspirin (200 mg/kg body weight of rat equivalent to 2222 mg of clinical dose orally).[7] Aspirin was taken as a standard anti-inflammatory drug. Group III received vildagliptin (9 mg/kg body weight of rat equivalent to 100 mg of clinical dose orally)[8] Group IV received saxagliptin (0.45 mg/kg body weight of rat equivalent to 5 mg of clinical dose orally).[8]

Carrageenan-induced rat paw edema

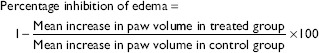

Drugs were administered in a single dose prior to induction of acute inflammation by injecting carrageenan (0.05 ml of 1% suspension in 0.9% saline) in subplantar region of the left hind paw. A mark was made on the hind limb at the malleolus to facilitate uniform dipping at subsequent readings. Paw edema volume was measured in milliliters with the help of a plethysmograph by mercury displacement method at 0 h, i.e., immediately after injecting carrageenan. The same procedure was repeated at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h after injecting carrageenan.[9] Percentage inhibition of edema in various drug-treated groups was calculated using the following formula:[10]

Foreign body-induced granuloma method

The subacute inflammation was induced in each rat by implanting subcutaneously two sterile cotton pellets weighing 10 mg each and two sterile grass piths (25 mm × 2 mm each) in axilla and groin, respectively, under thiopentone anesthesia with aseptic precautions. Wounds were then sutured and animals were caged individually after recovery from anesthesia. Treatment was started on the day of implantation and continued for 10 days.[11,12]

On the 11th day, the rats were sacrificed to remove the cotton pellets and grass piths. The grass piths were preserved in 10% formalin for histopathological studies. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and the granulation tissue in each group was studied microscopically. The pellets, free from extraneous tissue, were dried overnight at 60°C to note their dry weight. Net granuloma formation was calculated by subtracting initial weight of the cotton pellet (10 mg) from the weights recorded. Mean granuloma dry weight for various groups was calculated and expressed as mg/100 g body weight. Percentage inhibition of granuloma dry weight was calculated using the following formula:[10]

Statistical analysis

The data for all the groups were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean and were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by post hoc Dunnett's test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using the statistical software GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, California, USA).

RESULTS

In the present study, DPP-4 inhibitors, namely saxagliptin and vildagliptin were investigated for their anti-inflammatory effects using acute and subacute models of inflammation in male Wistar rats. Aspirin was taken as a standard anti-inflammatory drug.

Acute inflammation (carrageenan-induced paw edema)

A significant reduction in mean edema volume in milliliters (ml) as measured by mercury displacement using a plethysmograph was observed in aspirin, saxagliptin, and vildagliptin groups as compared to the control group.

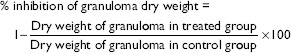

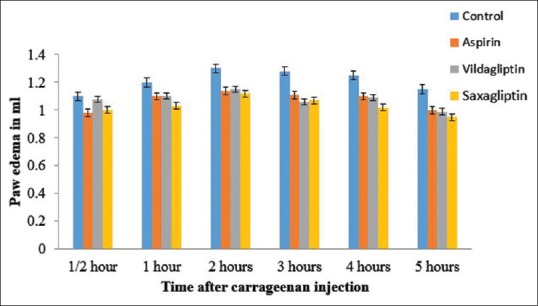

The mean edema volumes in ml as measured by mercury displacement using a plethysmograph for control group at ½, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h were 1.1 ± 0.02, 1.2 ± 0.01, 1.3 ± 0.02, 1.28 ± 0.06, 1.25 ± 0.02, and 1.15 ± 0.04, respectively [Table 1 and Figure 1], whereas the corresponding mean values in the aspirin-treated group were 0.98 ± 0.02, 1.1 ± 0.01, 1.14 ± 0.03, 1.11 ± 0.03, 1.1 ± 0.02, and 1 ± 0.02, respectively [Table 1 and Figure 1] with percentage inhibition of 11%, 7.6%, 12.3%, 13.2%, 12%, and 13%, respectively, indicating significant anti-inflammatory activity of aspirin [Table 1].

Table 1.

Effect of various treatments on carrageenan-induced paw edema

Figure 1.

Effect of various treatments on carrageenan-induced rat paw edema

The mean edema volumes in ml for vildagliptin-treated group at ½, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h were 1.08 ± 0.01, 1.1 ± 0.02, 1.15 ± 0.01, 1.06 ± 0.03, 1.09 ± 0.02, and 0.99 ± 0.05, respectively [Table 1 and Figure 1] with percentage inhibition of 1.5%, 8.3%, 11.5%, 17.2%, 12.8%, and 14%, respectively, indicating significant anti-inflammatory activity of vildagliptin [Table 1].

The mean edema volumes in ml for saxagliptin-treated group at ½, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h were 1 ± 0.02, 1.03 ± 0.02, 1.12 ± 0.04, 1.07 ± 0.03, 1.02 ± 0.04, and 0.95 ± 0.03, respectively [Table 1 and Figure 1] with percentage inhibition of 9%, 14%, 13.8%, 16.4%, 18.4%, and 17.4%, respectively, indicating significant anti-inflammatory activity of saxagliptin [Table 1]. The above results clearly indicate the anti-inflammatory activity of vildagliptin and saxagliptin.

Subacute inflammation (foreign body-induced granuloma method)

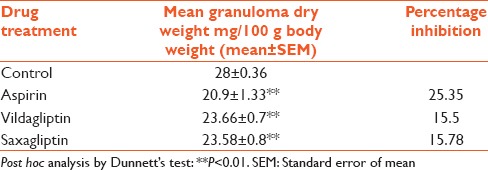

The mean dry weight of 10-day-old granuloma, expressed as mg per 100 g body weight, in control group was 28 ± 0.36, whereas in aspirin-treated group, it was significantly decreased with a mean value of 20.9 ± 1.33 and a percentage inhibition of 25.35%. Similarly, vildagliptin- and saxagliptin-treated groups exhibited significantly decreased mean granuloma dry weight with mean values of 23.66 ± 0.7 and 23.58 ± 0.8, respectively, and corresponding percentage inhibition of 15.5% and 15.78%, respectively [Table 2].

Table 2.

Effect of various treatments on granuloma dry weight

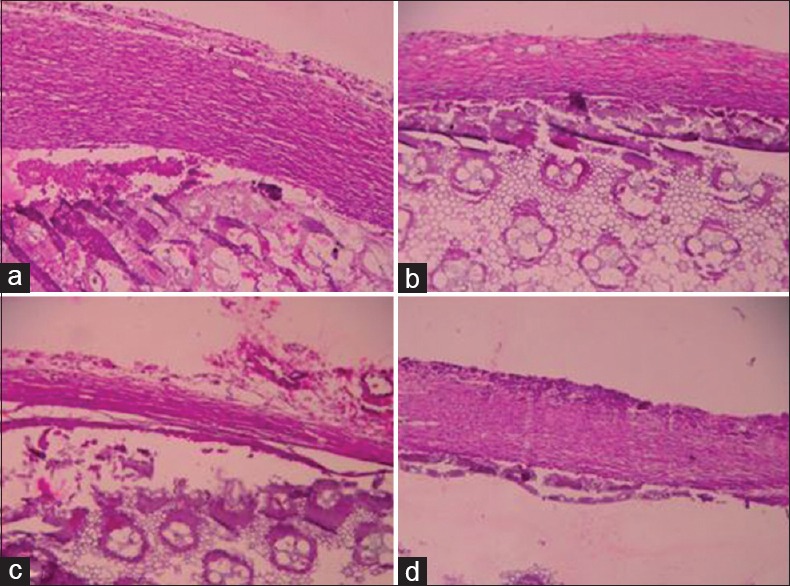

Histopathological studies

The sections of the grass piths when stained with hematoxylin and eosin showed abundant fibrous tissue in the control group, but revealed reduced number of fibroblasts, decreased granulation tissue, collagen content and fibrous tissue in aspirin, vildagliptin and saxagliptin treated groups [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of grass pith with granulation tissue. (a) Control group; (b) aspirin group; (c) vildagliptin group; (d) saxagliptin. As compared to control group; aspirin-, vildagliptin- and saxagliptin-treated groups show reduced number of fibroblasts, decreased granulation tissue, collagen content, and fibrous tissue (H and E, ×40)

DISCUSSION

In the present study, DPP-4 inhibitors, namely vildagliptin and saxagliptin were investigated for their anti-inflammatory effects using acute and subacute models of inflammation in male Wistar rats.

The findings of the present study indicate that vildagliptin and saxagliptin have significant anti-inflammatory activity comparable to that of aspirin in an acute model of inflammation as indicated by carrageenan-induced rat paw edema model. Both vildagliptin and saxagliptin also showed significant anti-inflammatory activity in the subacute model of inflammation as indicated by change in weight of cotton pellets and decreased granulation tissue induced by grass pith implantation in histopathological studies.

Although saxagliptin is frequently prescribed in patients with diabetes mellitus, its anti-inflammatory potential has not been looked into by any studies done in the past which has been proven by the present study.

DPP-4 inhibitors by inhibiting the enzyme responsible for the breakdown of GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) prolong the half-life of endogenously released GLP-1 and GIP, leading to enhanced glucose-dependent insulin secretion and decreased glucose-dependent glucagon secretion. DPP-4 inhibitors effectively improve glycemic control (significantly reduce glycated hemoglobin [A1C], fasting plasma glucose, and postprandial glucose [PPG]) when used as monotherapy, as add-on to metformin, as add-on to sulfonylureas with or without metformin, as add-on to thiazolidinediones with or without metformin, and as an add-on to insulin with or without metformin.[13] Oral DPP-4 inhibitors, therefore, represent an important addition to the oral treatment options currently available for the management of T2DM. They offer several advantages over conventional therapies and newer GLP-1 analogs such as being orally available, relative freedom from side effects, improved postprandial glycemia, and the ability of potentiating the actions of GLP-1 as well as GIP.[14]

DPP-4 inhibitors have also been found to attenuate the progression of atherosclerosis by reducing the levels of inflammatory markers such as high-sensitive C-reactive protein and TNF-α as well as reducing the lipid peroxide malonyl dehydrogenase (MDA) and enhancing glutathione (GSH).[15] MDA and GSH have been considered as specific indicators of oxidative stress. MDA level can be used as a marker of lipid peroxidation and its measurement gives a direct evidence for low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol oxidation and useful in predicting free radical-induced injury. Vildagliptin by significantly reducing aortic MDA level suggests a decrease in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequent lipid peroxidation.[15] In addition, vildagliptin by enhancing GSH levels in aortic tissue maintains an antioxidant reserve, which is important for vascular protection against lipid peroxide.[15]

Other effects of these drugs are found to be activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)[16] and suppression of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)[16]. Activation of AMPK, an energy sensor ubiquitously expressed in vascular cells, has been reported to possess anti-atherosclerotic effects by upregulating the Akt/endothelial nitric oxide synthase/nitric oxide (eNOS)/NO signaling pathway, leading to the suppression of p38-mediated nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) activation and consequently, suppression of downstream inflammatory responses. Suppression of MAPK also has been reported to have beneficial effects in atherosclerosis through inhibiting adhesion molecules and anti-inflammation effects.[16]

In a study involving male LDL receptor-deficient (LDLR–/–) mice which were fed a high-fat diet or normal chow diet for 4 weeks and then randomized to vehicle or alogliptin, a high-affinity DPP-4 inhibitor, it was found that DPP-4 inhibition reduced atherosclerosis and improved vascular function. DPP-4 inhibition resulted in improvements in insulin resistance, PPG, inflammatory cytokines, and adipokines in the plasma.[17] A reduction in inflammatory monocytes was discernible in the adipose tissue, along with improvement in adipocyte area and a reduction in visceral adipose content.[17] There was a reduction in monocytes in the plaque-expressing proinflammatory genes. These changes suggest potent effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on inflammation, mediated potentially via its effects on monocyte recruitment to tissue niches, and alteration of monocyte activation, as evidenced by an increase in the markers of alternate macrophage activation such as CD163 and Ym-1 in adipose tissue macrophages. Both GLP-1 (via DPP-4 inhibition) and non GLP-1 mechanisms may activate phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase -Akt-eNOS, may improve nitric oxide release, and may confer additional benefits. It has been concluded that DPP inhibitors have broad pleiotropic effects and hence, these agents have a potential role in retarding atherosclerosis and related complications in T2DM.[17]

In a trial in which 22 patients with T2DM were randomized to receive either 100 mg daily of sitagliptin or placebo for 12 weeks, glycosylated hemoglobin fell significantly in patients treated with sitagliptin. Fasting GLP-1 concentrations increased significantly, whereas the mRNA expression in mononuclear cell of CD26, the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα, the receptor for endotoxin – toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4), TLR-2, and proinflammatory kinases-c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1, inhibitory-kB kinase (IKKβ), and that of the chemokine receptor CCR-2 fell significantly after 12 weeks of sitagliptin. TLR-2, IKKβ, CCR-2, and CD26 expression and NF-kB binding also fell after a single dose of sitagliptin. There was a fall in the protein expression of c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1, IKKβ, and TLR-4 and in plasma concentrations of C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and free fatty acids after 12 weeks of sitagliptin.[18]

In an animal model of obese type 2 diabetes, the Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rat, sitagliptin prevented β-cell dysfunction and evolution of pancreatic damage. The protective effects afforded by this DPP-4 inhibitor may derive from the improvement of metabolic profile and from cytoprotective properties. In fact, sitagliptin was able to reduce Bax/Bcl2 ratio, suggestive of an antiapoptotic effect, and completely prevented the increased pancreas overexpression of IL-1 beta and tribbles pseudokinase 3 that was found in the untreated diabetic animals, thus demonstrating an anti-inflammatory action.[2]

The fructose-fed hypertensive rats experimental model presents metabolic syndrome criteria, vascular and cardiac remodeling, and vascular inflammation due to increased expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and pro-atherogenic cytokines. Administration of vildagliptin effectively reduced superoxide production by reducing the activity of NAD(P) H oxidase and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances, and it was also able to normalize the eNOS activity. Furthermore, most likely by inhibiting the activity of NAD(P) H oxidase, vildagliptin was also able to normalize the endothelial oxidative status. Chronic treatment with vildagliptin returned the expression levels of proatherogenic cytokines, including vascular endothelial growth factor, leptin, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, and MCP-1 to control values. In addition, vildagliptin administration significantly reduced macrophage inflammatory protein-3 alpha and TNF-alpha, demonstrating the important role that the incretin system plays in vascular inflammation in this experimental model.[19]

Recently, it has been found that systemic insulin resistance contributes to dysregulated insulin and metabolic signaling in the heart and the development of diastolic dysfunction.[20] In addition, insulin resistance which is accompanied with chronic low-grade inflammation contributes to the pathogenesis of hypertension and chronic heart failure.[20] Hence, there has been increased interest in restoring energy metabolism and establishing anti-inflammatory therapies for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.[20] In a study, isoproterenol-treated rats were used to evaluate whether vildagliptin prevents left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy and improves diastolic function.[21] Histological analysis showed that vildagliptin attenuated the increased cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and perivascular fibrosis. These effects were accompanied by the amelioration of expression of genes associated with glucose uptake and inflammation. In the group which received oral vildagliptin along with subcutaneous isoproterenol, quantitative polymerase chain reaction showed attenuation of increased mRNA expression of IL-6, insulin-like growth factor-l (IGF-1), and restoration of decreased mRNA expression of glucose transporter Type 4. It was concluded that vildagliptin may reduce inflammation in the heart by reducing the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 mRNAs in myocardial tissue of isoproterenol-treated rats. Recent evidence has pointed that IGF1 is said to play a role in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Thus, a change in cytokine expression by vildagliptin may contribute to the prevention of LV hypertrophy.[21]

Inflammation embraces mechanisms such as oxidative stress, neovascularization, apoptosis, and cellular proliferation and has been implicated to play an important role in microvascular as well as macrovascular complications of diabetes.[22] There is a need of experimental work to be done for evaluating drugs for their effectiveness in protecting against inflammatory processes of diabetic complications. Obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease seem to share a common metabolic milieu characterized by insulin resistance and inflammation. The inflammation is mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and ROS. In addition to these levels of AMPK, MAPK and apoptotic factors seem to be altered which also triggers off or worsens the existing inflammation. Amelioration in the inflammatory processes can be judged by improvement in the levels of these markers, which is demonstrated by DPP4 inhibitors.

CONCLUSION

The present study suggests that the DPP4 inhibitors, namely vildagliptin and saxagliptin have significant anti-inflammatory potential. Based on the findings of the present study and the available literature, it can be concluded that the anti-inflammatory potential of DPP 4 inhibitors could help to reduce the cardiovascular complications of Type 2 diabetes apart from their glucose-lowering potential. They may also provide clinical benefits to a large number of people affected by the obesity epidemic and the related cluster of metabolic disorders collectively called the metabolic syndrome.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mega C, Vala H, Rodrigues-Santos P, Oliveira J, Teixeira F, Fernandes R, et al. Sitagliptin prevents aggravation of endocrine and exocrine pancreatic damage in the zucker diabetic fatty rat – Focus on amelioration of metabolic profile and tissue cytoprotective properties. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathieu P, Lemieux I, Després JP. Obesity, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:407–16. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alonso N, Julián MT, Puig-Domingo M, Vives-Pi M. Incretin hormones as immunomodulators of atherosclerosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012;3:112. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saraiva FK, Sposito AC. Cardiovascular effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:142. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0142-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly AS, Bergenstal RM, Gonzalez-Campoy JM, Katz H, Bank AJ. Effects of exenatide vs. Metformin on endothelial function in obese patients with pre-diabetes: A randomized trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012;11:64. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-11-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweetman SC. Martindale the Complete Drug Reference. 36th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscazo J. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winter CA, Risley EA, Nuss GW. Carrageenin-induced edema in hind paw of the rat as an assay for antiiflammatory drugs. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1962;111:544–7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-111-27849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta SK. Drug Screening Methods. 2nd ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patil PA, Kulkarni DR. Effect of antiproliferative agents on healing of dead space wounds in rats. Indian J Med Res. 1984;79:445–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner RA. Screening Methods in Pharmacology. New York, London: Academic Press Inc.; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornell S. Type 2 diabetes treatment recommendations update: Appropriate use of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. J Diabetes Metab. 2014;5:8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalra S. Emerging role of dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP-4) inhibitor vildagliptin in the management of type 2 diabetes. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:237–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadi NR, Abdulkadhim H, Almudhafer A, Majeed SA. Effect of vildagliptin on atherosclerosis progression in high cholesterol – Fed male rabbits. J Clin Exp Cardiol. 2013;4:249. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng Y, Li C, Guan M, Zheng Z, Li J, Xu W, et al. The DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin attenuates the progress of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein-E-knockout mice via AMPK- and MAPK-dependent mechanisms. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:32. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-13-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah Z, Kampfrath T, Deiuliis JA, Zhong J, Pineda C, Ying Z, et al. Long-term dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibition reduces atherosclerosis and inflammation via effects on monocyte recruitment and chemotaxis. Circulation. 2011;124:2338–49. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.041418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makdissi A, Ghanim H, Vora M, Green K, Abuaysheh S, Chaudhuri A, et al. Sitagliptin exerts an antinflammatory action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3333–41. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renna NF, Diez EA, Miatello RM. Effects of dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibitor about vascular inflammation in a metabolic syndrome model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandavia CH, Aroor AR, Demarco VG, Sowers JR. Molecular and metabolic mechanisms of cardiac dysfunction in diabetes. Life Sci. 2013;92:601–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyoshi T, Nakamura K, Yoshida M, Miura D, Oe H, Akagi S, et al. Effect of vildagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor, on cardiac hypertrophy induced by chronic beta-adrenergic stimulation in rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:43. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-13-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navale AM, Paranjape AN. Role of inflammation in development of diabetic complications and commonly used inflammatory markers with respect to diabetic complications. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;5(Suppl 2):1–5. [Google Scholar]