Abstract

The transcriptional co-activator Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1), a key nuclear effector of the Hippo pathway, is a potent oncogene, and yet, the interaction between YAP1 and androgen receptor (AR) remains unexplored. Here we identify YAP1 as a physiological binding partner and positive regulator of AR in prostate cancer. YAP1 and AR co-localize and interact with each other predominantly within cell nuclei by an androgen-dependent mechanism in a hormone naive and an androgen-independent mechanism in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells. The growth suppressor MST1 kinase modulates androgen-dependent and -independent nuclear YAP1–AR interactions through directly regulating YAP1 nuclear accumulation. Disruption of YAP1 signalling by genetic (RNAi) and pharmacological (Verteporfin) approaches suppresses AR-dependent gene expression and prostate cancer cell growth. These findings indicate that the YAP1–AR axis may have a critical role in prostate cancer progression and serves as a viable drug target.

Prostate cancer (PC) is a leading cause of cancer deaths among men in the Western countries1. Aberrant and deregulated androgen receptor (AR) signalling is a potent promoter of PC development, progression and metastasis2,3. AR gene amplification4, and mutations5 that increase or decrease sensitivity and/or specificity to its ligands6, oncogenic growth factor signalling7, and altered AR co-regulators8 have been shown to cause an aberrant AR activation, even in the presence of very little androgens in circulation9,10. Therefore, the antiandrogen therapy has some survival benefits for patients with advanced PC, but this strategy is temporary because the metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) emerges. Metastatic CRPC is lethal because there is no effective therapy for it. Despite recent advances10–13, the molecular mechanisms contributing to invasive CRPC are poorly understood. Lines of evidence suggest that AR is a key driver of this lethal disease, even in the presence of enzalutamide14, the second-generation potent inhibitor of AR, but the mechanism of how AR regains its functions and derives metastatic CRPC remains obscure.

AR is a transcription factor and a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily15. AR has three major functional domains: an NH2-terminal transactivation domain (NTD) that mediates a ligand-dependent or ligand-independent activation of AR16, a DNA binding domain (DBD) that interacts with cis-DNA, called the androgen response element (ARE), and a COOH-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD) that mediates dimerization and a ligand-dependent transactivation of AR17. Studies based on cell models—mostly in COS7 cells—indicate that unliganded and structurally intact AR normally resides within the cytoplasm as an inactive form through interaction with heat shock proteins (HSPs) such as hsp9018. On ligand binding, AR disassociates from hsp90 and then enters into cell nuclei, where it binds to the ARE and regulates its target gene expression through interaction with co-regulatory proteins (that is, co-activators or co-repressors)17,19. Altered expression of the AR co-regulators that comprise scaffold proteins with or without chromatin modifying functions has been implicated in metastatic CRPC8,20,21. Since AR-targeted therapy has limited clinical benefits, there is a great deal of interest in targeting the AR regulators to improve current therapies.

YAP1 (Yki in Drosophila) is a transcriptional co-activator and regulates diverse cellular biology including growth22, apoptosis23, differentiation24, cell–cell interactions24,25, epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT)26,27, oncogenic cell transformation28 and chemoresistance29,30. YAP1 interacts with various transcription factors such as TEF/TEAD31, SMADs32 or TBX533 to exert its biologic functions in the cell. MST1/2 and LATS1/2, core kinase components of the Hippo pathway are potent negative regulators of YAP1. The cascade of MST1/2 and LATS1/2 signalling was demonstrated to inactivate YAP1 by promoting its inhibitory Ser127 (S127) site phosphorylation, cytoplasmic retention and proteasome-mediated degradation34. Activation of YAP1 due to the gene amplification or the loss-of-function of MST1/2 or LATS1/2 is linked to the aetiology of many cancers including lung35, colon36, ovarian37, head and neck38, liver39,40, meningioma41, thyroid42 and stomach43. In addition, emerging evidence suggests that YAP1 may also play a critical role in the pathobiology of PC44. However, the role and mechanism of YAP1 in PC remains to be explored.

In this study, we investigate the biochemical and functional association between YAP1 and AR in PC. We demonstrate that YAP1 and AR co-localize and form protein complexes primarily in cell nuclei and that the complex formations between the two proteins are androgen-dependent in castration-sensitive (CS), but are androgen-independent (AI) in CR PC cells. In addition, we show that MST1 is a key negative regulator of YAP1–AR interactions, which may play crucial role in AR-dependent gene expression and PC cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Our study identifies new functions of the YAP1 interaction with AR.

Results

YAP1 and AR interact with each other in prostate cancer cells

To explore the relationship between YAP1 and AR, we utilized PC clinical samples and cell models and employed cellular, molecular and biochemical approaches. In this study, well-established CS or hormone naive LNCaP and CR or hormone refractory C4-2 PC cells were extensively used because they are genetically related and express functional AR, but differentially respond to androgen hormone signalling for their growth in vitro and in vivo45. The C4-2 cell line was generated by in vivo selection of LNCaP cells recycling through castrated mice45.

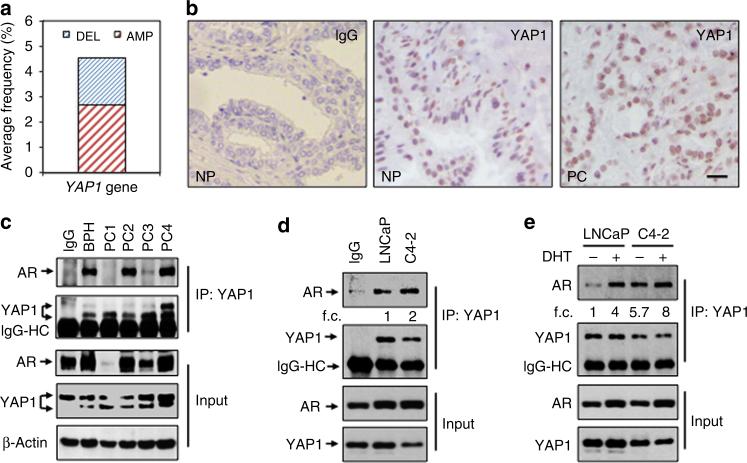

First, we analysed the publicly available YAP1 data using the www.cbioportal.org online platform. The analysis indicated that unlike other cancers such as ovarian or cervical cancer, about 3–6% of PC cases showed genetic alterations in YAP1 gene (that is, deletion or amplification; Fig. 1a). Second, we assessed the expression of YAP1 protein in the histologic sections of normal prostate (NP) and PC tissues by immunohistochemistry (IHC). YAP1 protein was abundantly stained in NP and PC tissues (Fig. 1b, middle and right panels, respectively). Notably, staining of YAP1 protein, which was predominantly accumulated in cell nuclei, was not uniform and showed heterogenic features (that is, overstaining, under-staining or no staining) within the same samples and amongst the cases. IgG control did not visualize YAP1 protein expression in the tissue (Fig. 1b, left panel), indicating that YAP1 staining was specific.

Figure 1. YAP1 and AR form protein complexes in prostate cancer tissues and cells.

(a) Genetic alterations of YAP1 gene in human prostate cancer compiled from the www.cbioportal.org online platform. DEL: Deletion, AMP: Amplification. (b) Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of YAP1 protein in human normal prostate (NP, n = 9) and prostate cancer (PC, n = 22) clinical samples. (c) Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) and western blot (WB) analysis of AR and YAP1 proteins in total lysates obtained from fresh-frozen non-cancerous prostate or benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and PC tissues. Tissue lysate consisting of high levels of both YAP1 and AR proteins was used in IgG control for the representation of other samples subjected to the co-IP and WB. (d) Co-IP and WB analysis of AR and YAP1 proteins in total lysates obtained from castration-sensitive LNCaP and castration-resistant C4-2 cells grown in serum-fed conditions. Mixture (1:1 ratio) of lysates from LNCaP and C4-2 cells was used in IgG control (e) Co-IP and WB analysis of AR and YAP1 proteins in total lysates obtained from LNCaP and C4-2 cells treated with vehicle (EtOH) and androgen (10 nM, Dihydrotestosterone, DHT) in charcoal-striped serum (CSS) growth conditions for 24 h. Co-IP and WB experiments were performed with antibodies to corresponding proteins. IgG was used as negative control in co-IP/WB experiments. Data are representative of two independent experiments. f.c., fold change; Scale bar, 100 mm.

To determine whether native YAP1 and AR biochemically interact with each other in vivo, we performed co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) and western blot (WB) experiments utilizing total lysate isolated from fresh-frozen normal and cancerous human prostate tissue specimens. The results showed that endogenous YAP1 and AR formed protein complexes (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 1a). Similarly, co-IP and WB experiments demonstrated that YAP1 and AR interacted with each other in total lysate obtained from LNCaP and C4-2 cells that were grown in serum-fed conditions (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. 1b). The interactions between the two proteins were specific because IgG control did not show any visible interaction (Fig. 1c,d). In addition, androgen (dihydrotestosterone: DHT) exposure increased YAP1–AR interactions four-fold in LNCaP cells compared with vehicle (EtOH) control (Fig. 1e, lane 2 versus lane 1; Supplementary Fig. 1c). Surprisingly, however, YAP1–AR interactions occurred independently of DHT exposure in C4-2 cells (Fig. 1e, lane 3; Supplementary Fig. 1c). Although the C4-2 cell line does not require androgens for growth and survival45, it still responds to androgen hormone signalling due to the expression of functional AR. For this reason, YAP1–AR interactions were further enhanced by DHT exposure in C4-2 cells when the result was normalized to total YAP1 protein (Fig. 1e, lane 3 versus lane 4; Supplementary Fig. 1c).

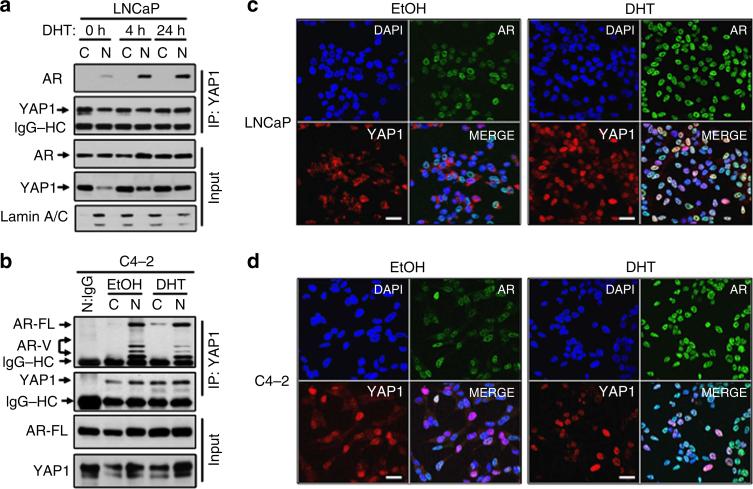

YAP1 and AR interactions occur in cell nuclei

To identify the subcellular location where YAP1 and AR primarily interact and whether that is regulated by androgen, we performed co-IP and WB experiments utilizing cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions isolated from LNCaP cells at 0, 4 and 24 h post DHT treatment. Co-IP and WB showed that YAP1 and AR interacted predominantly in cell nuclei and that androgen exposure increased AR presence in the YAP1 immune complex in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 2a). Here we want to clarify that AR appears to be equally distributed between the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions without androgen exposure (Fig. 2a, lane 1 and 2, input). One possible explanation for this is that the AR in LNCaP cells has a Thr877Ala mutation, and this mutation has been implicated to favour AR nuclear localization in the absence of androgen46. Nevertheless, on androgen exposure, the majority of AR localizes to the cell nuclei, as demonstrated by WB (Fig. 2a, lane 3 versus 4 and 5 versus 6, input) and immunofluorescence imaging (Fig. 2c left panel versus right panel). Thus, our data are internally consistent and aligned with the published literature46. In addition, androgen exposure increased the abundance of YAP1 in the AR immune complex compared with vehicle exposure (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. Cell nuclei are the primary interaction sites of YAP1 and AR proteins.

(a,b) Co-IP and WB analysis of AR and YAP1 proteins in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions obtained from (a) LNCaP cells treated with DHT for 0, 4 or 24 h and (b) from C4-2 cells treated with EtOH or DHT for 24 h in CSS growth conditions. Co-IP and WB were probed with antibodies to corresponding proteins. Lamin A/C was used as a nuclear extraction control. (c,d) Co-immunofluorescence (co-IF) analysis of AR and YAP1 proteins in LNCaP (c) and C4-2 (d) cells that were treated with EtOH and DHT in CSS conditions for 24 h. Alexa Fluor 488 stained AR (green), Cy3 stained YAP1 (red) and DAPI stained cell nuclei (blue). Magnification: 40×. Micrographs are the representation of multiple confocal images. Data are from two independent experiments. C, Cytoplasm; N, Nuclei, Scale bar, 100 μm.

Nevertheless, unlike LNCaP, the interaction between YAP1 and AR in C4-2 cells was independent of androgen exposure, as shown by co-IP and WB experiments (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 2c). In addition, the protein complex formation between YAP1 and AR were reduced to undetectable levels in the nuclei of C4-2 cells with the RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated depletion of YAP1 (Supplementary Fig. 3a), indicating that YAP1 and AR interactions are specific. Moreover, co-immunofluorescence experiments demonstrated that compared with vehicle control, YAP1 and AR proteins co-localized in LNCaP cells in androgen-dependent manner (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Fig. 3b), whereas the co-localization was AI in C4-2 cells (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Fig. 3c). Taken together, the cell nuclei are likely the primary interaction site of YAP1 and AR proteins.

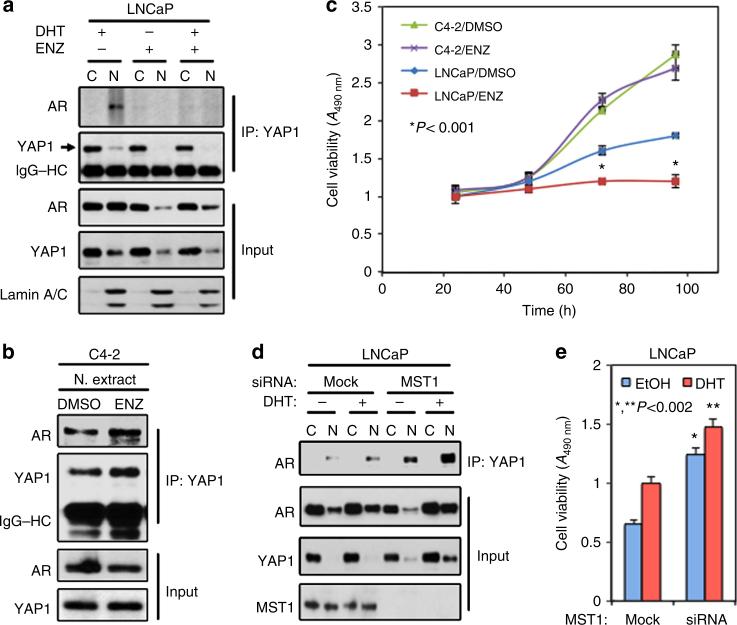

YAP1 and AR interactions are resistant to enzalutamide

To determine the impact of a potent AR inhibitor enzalutamide47 on YAP1–AR interactions, we repeated co-IP and WB experiments utilizing cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions isolated from LNCaP and C4-2 cells that were exposed to vehicle or enzalutamide with or without DHT. The results showed that enzalutamide attenuated androgen-dependent and AI interactions between nuclear YAP1 and AR proteins in LNCaP cells (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. 4a), but failed to block the nuclear interactions between two proteins in C4-2 cells (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. 4b). Accordingly, unlike LNCaP, enzalutamide also failed to attenuate the growth of C4-2 cells in vitro, regardless of androgen exposure (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Regulation of YAP1 and AR interactions by antiandrogen in vitro.

(a,b) Co-IP and WB analysis of AR and YAP1 proteins in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions obtained (a) from LNCaP cells that were treat with DMSO, enzalutamide (ENZ) plus or mice DHT or (b) from C4-2 cells that were treated with DMSO or enzalutamide without DHT exposure. (c) Analysis of LNCaP or C4-2 cell growth after treatment with DMSO or enzalutamide without DHT in vitro; *P<0.001. (d) Co-IP and WB analysis of AR and YAP1 proteins in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions obtained from LNCaP cells with or without MST1 knockdown plus or minus DHT treatment. Co-IP and WB were probed with antibodies to corresponding proteins at 24 in experiment (a,b) and at 48 h in experiment ‘d’ post treatment. Lamin A/C was used as a nuclear extraction control. Blots are representative of two independent experiments. C, Cytoplasm; N, Nuclei. (e) Analysis of LNCaP cell growth with or without MST1 knockdown plus or minus DHT treatment in vitro; *P<0.002. To assess growth, cell viability was determined by MTS assay at 72 h post treatment. Data (±s.e.) in c and e are representation of two independent experiments in triplicates.

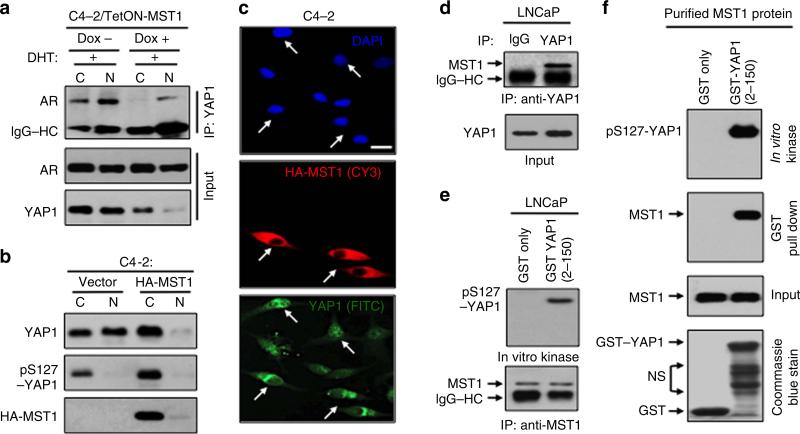

YAP1 and AR interactions are regulated by MST1

Previously, we reported that C4-2 cells express significantly lower levels of MST1 than LNCaP cells48. Results from this report and the above findings suggest that MST1 is a potent negative regulator of the YAP1–AR interaction. To test this possibility, we performed co-IP and WB experiments utilizing cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions obtained from LNCaP cells with or without MST1 knockdown plus or minus DHT treatment. Knockdown of MST1 markedly increased androgen-dependent and AI interactions between YAP1 and AR compared with mock controls (Fig. 3d; Supplementary Fig. 5a). Under the same experimental conditions above, MST1 depletion increased YAP1 nuclear localization with or without androgen exposure (Fig. 3d; Supplementary Fig. 5a). Accordingly, knockdown of MST1 promoted the androgen-dependent and AI growth of LNCaP cells in vitro (Fig. 3e), mimicking the functional behaviours of C4-2 cells (see Fig. 3b,c). Conversely, a controlled expression of the ectopic MST1 suppressed the interaction between YAP1 and AR proteins in C4-2 cells (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. 5b) and inhibition of YAP1–AR interactions coincided with reduction in nuclear abundance of YAP1 (Fig. 4b,c; Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Figure 4. Regulation of YAP1 phosphorylation by a direct MST1 signalling in PC cells.

(a) Co-IP and WB analysis of YAP1 and AR proteins in C4-2 cells with or without MST1 induction by doxycycline (Dox) followed by DHT exposure. (b) Analysis of YAP1 in cytoplasm and nuclear fraction in C4-2 cells transiently transfected with vector or HA-MST1. (c) IF analysis of YAP1 and HA-MST1 in C4-2 cells that were transiently transfected to express HA-MST1 in serum-fed conditions. Experiments in (a, b, c) were performed at 48 h post MST1 induction. (d) Co-IP and WB analysis of endogenous MST1 and YAP1 interactions in LNCaP cells. (e) In vitro kinase assay with GST–YAP1 (2–150) peptide and the MST1 immune complex precipitated from LNCaP cells. (f) GST–pull-down and in vitro kinase assays with the recombinant, purified MST1 kinase and GST–YAP1 (2–150) peptide. GST only peptide was used as a negative control in kinase and binding assays in (e) and (f). Experiments related to co-IP, WB and IF were performed with antibodies to corresponding proteins. Data are representative of two independent experiments. C, Cytoplasm; N, Nuclei; and Scale bar, 100 μm.

LATS1/2 (LATS) is a key intermediate for MST1 in the regulation of YAP1 (refs 39,49). Loss of LATS2 expression by promoter DNA methylation was implicated in PC50. In agreement with this observation, our analysis indicated that expression of LATS mRNA and protein was very low in LNCaP and C4-2 in comparison with that of the positive control HeLa or C2C12 cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b), as demonstrated by PCR and WB, respectively. These observations led us to believe that MST1 could regulate YAP1, independently of LATS. To test this hypothesis, we performed a series of biochemical assays. First, co-IP and WB showed that native MST1 and YAP1 formed protein complexes in LNCaP cells (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Fig. 7a). Second, in vitro kinase assays revealed that the MST1 immune complex that was precipitated from LNCaP cells was capable of phosphorylating the recombinant GST–YAP1 fusion peptide (residues 2–150) comprising the S127 phosphorylation site (Fig. 4e; Supplementary Fig. 7b). Third, GST pull-down and in vitro kinase assays demonstrated that recombinant, the preactivated MST1 kinase interacted with and phosphorylated the GST–YAP1–S127 peptide (Fig. 4f; Supplementary Fig. 7c). There was no detectable interaction or phosphorylation signal between MST1 and the GST only (control) peptide under these experimental conditions, indicating that the observation was specific. Fourth, more importantly, unlike LATS1/2, knockdown of MST1 reduced phospho-YAP1–S127 levels by 60% in C4-2 cells compared with mock control (Supplementary Fig. 13). These findings consistent with our notion suggest that MST1 is a potent direct negative regulator of YAP1 nuclear localization. This may be a mechanism by which MST1 negatively regulates YAP1–AR interactions.

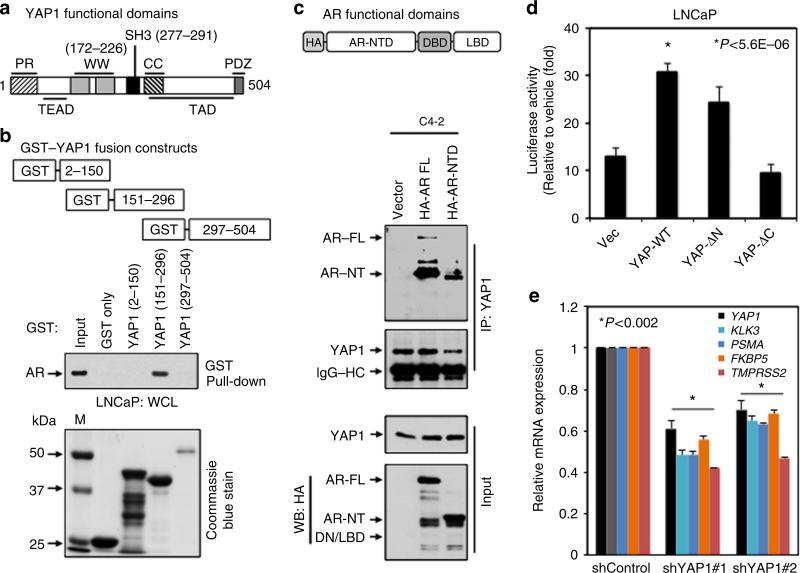

YAP1–WW/SH3 domain interacts with AR

YAP1 protein consists of several functional domains including proline-rich (PR), TEAD, WW, SH3, coiled-coil (CC), transactivation domain (TAD) and PDZ domains (Fig. 5a). To map the YAP1 domain that facilitates the interaction with AR, we generated GST–YAP1–WT and GST–YAP1 truncation mutant constructs comprising PR and TEAD domains (GST–YAP1–PR/TEAD (residues 2–150), WW and SH3 domains (GST–YAP1–WW/SH3; residues 151–296) or CC, TAD and PDZ domains (GST–YAP1–CC/TAD/ PDZ; residues 297–504) and attempted to express them in bacteria as a recombinant protein (Fig. 5b, Coommassie blue stain; Supplementary Fig. 8a). Due to technical difficulties, we were unable to express the full-length YAP1 as a GST fusion protein at all, even with several attempts. Luckily, we would be to successfully express YAP1–PR/TEAD or YAP1–WW/SH3 domain as a GST fusion peptide. In addition, we managed to express GST–YAP1–CC/TAD/PDZ fragment, though the yield was much lower than GST–YAP1–PR/TEAD and GST–YAP1–WW/SH3 peptides. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing the expression of YAP1 as a GST fusion protein in bacteria.

Figure 5. Mapping the binding domain between YAP1 and AR and assessing the significance of the binding.

(a) Schematic representation of the functional domains of YAP1. (b) GST–pull-down with GST–YAP1 fusion peptides. The binding of AR protein to GST–YAP1 peptide was probed with WB using the AR specific antibody. Total cell lysate from LNCaP was used as a source of AR in GST–pull-down experiment. M, Marker. (c) Co-IP and WB analysis of endogenous YAP1 interacting with the exogenous HA–AR full-length (FL), HA–AR–NTD or AR–DBD–LBD deletion mutant in C4-2 cells. (d) AR-responsive PSA promoter reporter activity; *P<5.6E–06. LNCaP cells were transiently transfected with PSA-Luc and Vector control, YAP1–WT, YAP1-ΔN (58-504 residues), or YAP1-ΔC (2–290 residues) construct, followed by EtOH vehicle or androgen (10 nM DHT) treatment for 48 h. (e) Quantitative PCR analysis of YAP1 and well-characterized AR responsive genes KLK3, PSMA, FKBP5 and TMPRSS2 in LNCaP cells that were transiently transfected with control shRNA or two different YAP1 shRNAs, followed by DHT treatment in CSS growth condition; *P<0.002. Quantitative RT–PCR with total RNA was performed at 24 h post DHT treatment or at 72 h post transfection. Data (±s.e.) are from two independent experiments in triplicate.

To identify the YAP1 domain that potentially interacts with AR, we performed GST–pull-down experiment utilizing recombinant GST only (negative control), GST–YAP1–PR/TEAD, GST–YAP1–WW/SH3 or GST–YAP1–CC/TAD/PDZ fusion peptide as a bait and total lysates isolated from LNCaP cells, which was used as a source of AR (Fig. 5b; Supplementary Fig. 8a). Although no interaction was observed between GST– YAP1–PR/TEAD and AR (Fig. 5b, lane 3), there was an apparent interaction between GST–YAP1–WW/SH3 and AR (Fig. 5b, lane 4). The observed interaction was specific because GST only peptide did not show any interaction (Fig. 5b, lane 2). Since the expression of GST–YAP1–CC/TAD/PDZ in bacteria resulted in a very low yield, we were unable to detect visible interactions between GST–YAP1–CC/TAD/PDZ and AR under these experimental conditions (Fig. 5b, lane 5). Nonetheless, this observation does not exclude a possible interaction between AR and YAP1–CC/TAD/PDZ domain. Taken together, WW/SH3 domain of YAP1 most likely facilitates the interaction with AR.

YAP1 interacts with amino-terminal domain of AR

The data in Fig. 2c have indicated that amino-terminal domain of AR may play a key role in its interaction with YAP1, because YAP1 interacted with both naturally occurring short (N-terminal) and the full-length (FL) AR forms. To test this hypothesis, we performed co-IP and WB experiments using total lysate obtained from C4-2 cells that were transiently transfected to express HA-tagged vector (control), AR-FL or AR–NTD truncation mutant (Fig. 5c; Supplementary Fig. 8b). The results showed that ectopic AR–FL or AR–NTD truncation mutant formed protein complexes with endogenous YAP1 (Fig. 5c, lane 2, 3, respectively). The HA-vector produces a very small peptide, which cannot be detected under these experimental conditions, possibly due to running off the 8% protein gel or degradation, did not show any apparent interaction with native YAP1 (Fig. 5c, lane 1; Supplementary Fig. 8b, lane 1). Thus, these findings further strengthen the specificity of interactions between YAP1 and AR and demonstrate that NTD of AR most likely provides a docking site for YAP1.

YAP1 regulates the expression of AR-responsive genes

To test the impact of YAP1 on AR responsive gene expression, we conducted prostate-specific antigen (PSA) promoter-driven luciferase reporter (p61-Luc) assays. PSA is a well-characterized AR-dependent gene and widely used to assess AR transactivation functions. LNCaP cells were transiently co-transfected with p61-Luc reporter along with mock (control), YAP1-WT (residues 2–504), YAP1-ΔN (residues 58–504) or YAP1-ΔC (residues 2–290) expression construct, followed by treatment with vehicle or DHT. Transient expression of YAP1–WT increased the androgen induction of PSA promoter reporter activation about threefold compared with mock vector (Supplementary Fig. 9a; Fig. 5d, respectively). Ectopic expression of YAP1-ΔN did not significantly affect androgen-induced PSA promoter activation, whereas YAP1-ΔC lacking its transactivation domain failed to enhance the androgen induction of PSA promoter activation. This indicates that C-terminal TAD domain of YAP1 plays key role in AR transactivation. In addition, quantitative PCR demonstrated that transient knockdown of YAP1 with two different short hairpin RNA (shRNA) significantly reduced the endogenous expression of other well-characterized AR-dependent genes KLK3, PSMA, FKBP5 and TMPRSS2 at mRNA levels relative to control shRNA (Fig. 5e). Moreover, transient over-expression of YAP1–WT significantly increased the growth of LNCaP cells in vitro, regardless of androgen exposure in comparison with vector control (Supplementary Fig. 9b). These observations suggest that YAP1 is a prominent regulator of AR-dependent signalling.

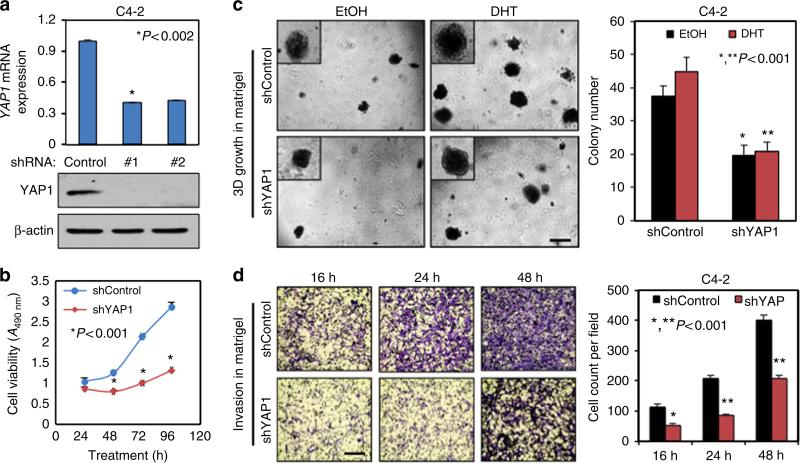

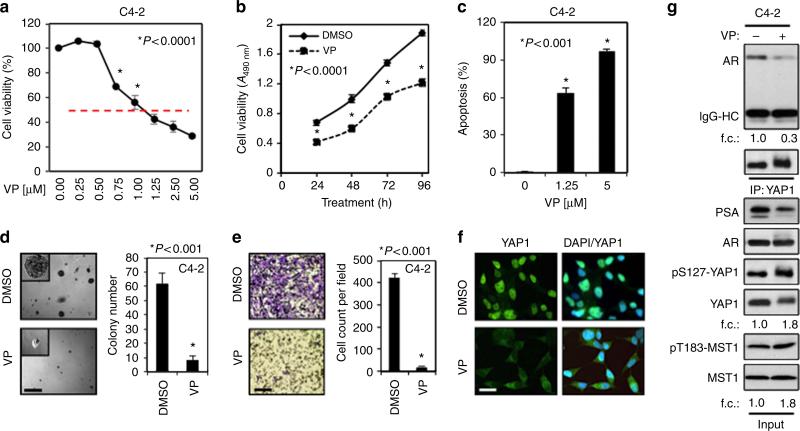

YAP1 silencing attenuates cell growth and invasion in vitro

To investigate whether disruption of YAP1 signalling alters the behaviours of PC cell growth, we generated stable YAP1 knockdown (shYAP1) or control (shControl) C4-2 cell models with the gene specific shRNAs (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Fig. 10a). Utilizing these cells, we performed series of biological assays. Knockdown of YAP1 decreased C4-2 cell growth in vitro in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 6b). Similarly, YAP1 knockdown by siRNA also attenuated the growth of LNCaP cells in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Likewise, YAP1 knockdown suppressed the androgen induction of C4-2 cell growth in monolayer (Supplementary Fig. 10c) and in three-dimensional (3D) cultures in comparison with controls (Fig. 6c). Cell cycle analysis showed that a cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 most likely caused growth retardation by YAP1 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 10d). In addition, YAP1 knockdown significantly diminished C4-2 cell invasion in Matrigel-coated Transwell chambers in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 6d). Besides, stable YAP1 knockdown attenuated the expression of AR target genes in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 10e), which was in agreement with the data in Fig. 5e.

Figure 6. RNAi silencing of YAP1 suppresses cell growth and invasion in vitro.

(a) Quantitative PCR and WB analysis of YAP1 mRNA and protein, respectively, in stable shControl or shYAP1 C4-2 cells; *P<0.002. (b) Time-dependent analysis of cell growth. Cell growth was assessed by MTS assay after 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post cell seeding in serum-fed conditions; *P<0.001. (c) Sphere formation in 3D Matrigel. Equal numbers of shControl and shYAP1 C4-2 cells were grown for 14 days in presence of either EtOH (vehicle) or 10 nM DHT in CSS conditions, and spheres were counted manually and presented in a graph; *,**P<0.001. (d) Time-dependent analysis of cell invasion through Matrigel-coated Transwell chamber; *,**P<0.001. Equal numbers of shControl and shYAP1 C4-2 cells were grown in CSS conditions (upper chamber) and serum-fed growth condition (lower chamber). Cells invading through the chamber were visualized by crystal violet staining (micrographs) and counted manually at 16-, 24- and 48-h post cell seeding. The graph is the quantification of invaded cells at indicated times. Data (±s.e.) are from two independent experiments in triplicates. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Alternatively, we repeated the above functional assays utilizing a small molecule inhibitor, verteporfin (VP). VP was identified as a potent inhibitor of YAP1 (ref. 51). VP exposure attenuated the growth of C4-2 cells in dose- and time-dependent manners (Fig. 7a,b). VP also suppressed the androgen induction of LNCaP or C4-2 cell growth (Supplementary Fig. 11a-c). Similarly, VP also suppressed the growth of AR-negative PC3 and DU145 cells in a similar manner (Supplementary Fig. 11d). However, PC3 and DU145 cells were relatively resistant to VP compared with LNCaP and C4-2 cells. VP also caused apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7c; Supplementary Fig. 11e) and cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 (Supplementary Fig. 11f). Likewise, VP profoundly attenuated the ability of C4-2 cells to form spheres in Matrigel (Fig. 7d) and to invade through Matrigel-coated Transwell chamber (Fig. 7e).

Figure 7. Pharmacological inhibition of YAP1 attenuates the growth and invasion abilities of the cell in vitro.

(a,b) Assessing the impact of Verteporfin (VP) on cell growth. C4-2 cells were treated with increasing doses of VP for 48 h or DMSO (vehicle) or 1.25 μM VP for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. Cell growth was assessed by MTS assay post treatment; *P<0.0001. (c) Apoptosis assay. C4-2 cells were treated with increasing doses (0, 1.25 or 5 μM) of VP for 48 h. Propidium iodide and Annexin V stained cells were analysed by flow cytometry to assess apoptosis; *P<0.001. (d) Sphere formation in 3D Matrigel assay. C4-2 cells grown in Matrigel under serum-fed conditions were treated with DMSO or 1.25 μM VP for 10 days. Spheres in Matrigel (micrographs) were counted manually and then plotted (graph); *P<0.001. (e) Cell invasion in Matrigel-coated Transwell. C4-2 cells were treated with DMSO (vehicle) or 1.25 μM VP. Invaded cells that were stained with crystal violet (micrographs) were counted and then plotted (graph); *P<0.001. (f) IF staining of C4-2 cells that were treated with DMSO or 1.25 μM VP for 24 h in serum-fed growth conditions. YAP1 protein (green) with Alexa Fluor 488 and nuclei (blue) with DAPI were visualized by confocal microscopy. Data (±s.e.) are from two independent experiments in triplicate; *P<0.001. (g) Co-IP and WB analysis of YAP1 and AR proteins in total lysate from C4-2 cells that were treated with DMSO or 1.25 μM VP. Co-IP and WB were probed with antibodies to corresponding proteins. f.c.: fold change. Scale bar, 100 μm.

To gain more insights into how VP suppressed PC cell growth, we conducted immunofluorescence, co-IP and WB experiments to see if VP exposure impairs YAP1 nuclear localization and its interaction with AR. As proposed, VP exposure suppressed YAP1 nuclear localization (Fig. 7f) and YAP–AR interactions (Fig. 7g; Supplementary Fig. 12a), without affecting AR protein expression or its nuclear localization relative to control (Fig. 7g, input; Supplementary Fig. 12b, respectively). In agreement with these observations, decreases in YAP1–AR interactions by VP were accompanied with inhibition of AR-dependent PSA protein expression (Fig. 7g, input; Supplementary Fig. 12c). Moreover, WB and immunofluorescence experiments showed that unlike vehicle control, VP exposure increased phospho-YAP1–S127 protein levels (Fig. 7g, input; Supplementary Fig. 12d,e, respectively).

To determine whether increases in YAP1 phosphorylation by VP correlates with the induction of Thr183 (T183) phosphorylation, a key mediator of MST1 kinase activity52, we assessed the levels of total and phospho-YAP1–S127 along with total and phosho-MST1-T183 by WB in C4-2 cells. Relative to control, VP exposure increased phospho-MST1-T183 levels that coincided with upregulation of phospho-YAP1–S127 (Fig. 7g, input; Supplementary Fig. 12f, indicating that VP promotes YAP1-S127 phosphorylation by activating MST1). In addition, compared with control siRNA, transient transfection of LATS1/2 siRNA did not alter the VP induction of phosho-YAP1–S127-, whereas transient transfection of MST1 siRNA caused a significant reduction in YAP1–S127 phosphorylation by VP (Supplementary Fig. 13). Moreover, VP significantly decreased the expression of AR-responsive genes KLK3, FKBP5, and TMPRSS2 without affecting AR protein levels (Supplementary Fig. 14a, Fig. 7g, input, respectively). These observations suggest that MST1 is a potent direct regulator of YAP1 under conditions where LATS1/2 expression or functions is lost.

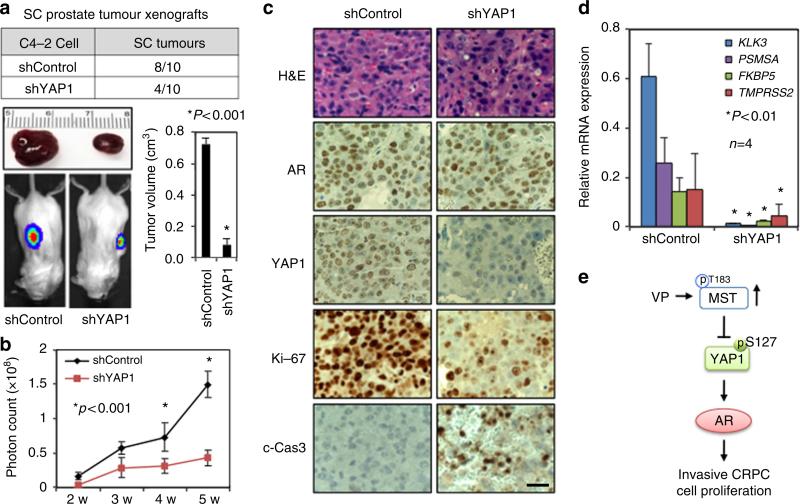

YAP1 silencing suppresses prostate tumour xenografts

To determine the biological significance of the above findings in vitro, we performed mouse xenograft experiments. Luciferase-tagged shControl or shYAP1 C4-2 cells were subcutaneously injected into immunodeficient male mice (n = 10 per condition) in the right and left flanks. Tumour growth was monitored for up to 5 weeks by luciferase imaging in live mice. Compared with shControl, YAP1 knockdown significantly reduced the number and size of tumours formed by shYAP1 C4-2 cells (Fig. 8a,b). To see whether YAP1 knockdown was able to suppress AR-dependent gene expression in vivo, we assessed the levels of PSA protein by WB along with YAP1 and AR in shControl and shYAP1 xenograft tissues (n = 4 per group). YAP1 silencing significantly reduced PSA protein levels without affecting AR protein levels relative to shControl (Supplementary Fig. 14b,c). Similarly, IHC analysis of AR and YAP1 expression in xenograft tissues sections further supported the WB data (Fig. 8c).

Figure 8. Disruption of YAP1 signalling suppresses prostate tumor xenografts.

(a) Table shows the number of tumours produced by shControl or shYAP1 C4-2 cells in immune deficient male mice (n = 10 per group). Representative tumour tissues are shown above the images. Micrographs show luciferase imaging of tumours in live animals. Tumours at the end of the fifth week post cell inoculation were dissected out at necropsy and their volumes were calculated and the data were plotted in a graph; *P<0.001. (b) Graph shows the quantification of photons from the luciferase imaging at each week; *P<0.001. (c) IHC analysis of YAP1, AR, c-Cas3 (cleaved-caspase 3), and Ki-67 proteins in xenografts tissue sections. Tissue sections were stained with YAP1, AR, Ki-67 or c-Cas3. Magnification: 40×. Micrographs are representative of multiple images. (d) Quantitative RT–PCR analysis of well-characterized AR-target genes KLK3 (PSA), PSMA, FKBP5 and TMPRSS2 in shControl and shYAP1 tumour xenografts. The qPCR data (±s.e.) are from two independent experiments in duplicates; *P<0.01. (e) Model summarizes the finding. Scale bar, 100 μm.

To determine whether suppression of tumour growth correlates with an impaired cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis, we evaluated the expression of Ki-67 proliferation and cleaved caspase 3 (c-Cas3) apoptotic markers in xenograft tissues by IHC. The results showed that a number of proliferative (Ki-67 positive) cells were reduced, while a number of apoptotic (c-Cas3 positive) cells were increased in shYAP1 C4-2 tumours compared with shControl (Fig. 8c). In addition, permanent YAP1 knockdown attenuated the expression of KLK3, PSMA, FKBP5 and TMPRSS2 mRNA in shYAP1 C4-2 xenografts relative to shControl (Fig. 8d). Taken together, these observations consistently demonstrate that the YAP1–AR axis is a key mediator of PC cell growth and survival, which can be negatively regulated by upstream MST1 signalling (Fig. 8e).

Discussion

In the current study, we have demonstrated that a nuclear interaction between YAP1 and AR that is regulated by MST1 signalling, possibly via a LATS1/2 bypass mechanism, may play a prominent role in the emergence of advanced PC. We provide convincing evidence to support this conclusion. Our data demonstrate that unlike CSPC cells, YAP1–AR interactions are AI and resistant to enzalutamide in CRPC cells. Our data also demonstrate that knockdown of MST1 in CS LNCaP cells increases YAP1 nuclear localization and YAP1–AR interactions, which coincided with augmented cell growth, independently of androgen exposure, and that the controlled expression of ectopic MST1 had the opposite effect. In addition, disruption of YAP1 signalling by a genetic or pharmacological approach caused the suppression of C4-2 cell growth in vitro or xenografts in vivo as well as inhibition of AR-dependent gene expression. These findings suggest that the YAP1–AR axis is a promising cancer drug target.

The Hippo pathway regulates tumorigenesis and organ size by restricting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis. MST1, related to Hippo (hpo) in Drosophila, is the key kinase component of the Hippo pathway53,54. In the conventional Hippo pathway signalling, MST1 phosphorylates and activates LATS that in turn phosphorylates and inactivates YAP1 (refs 53,54). Evidence suggests, however, that the regulation of YAP1 appears to be complex and governed by multiple mechanisms. For example, LATS was shown to phosphorylate and to prevent YAP1 nuclear localization independently of MST1 (ref. 55). Similarly, a study by Kapoor et al.56 showed that amplification of YAP1, which is uncommon in PC (Fig. 1a), was sufficient to promote cell survival in the animal model of pancreatic cancer and that these functions of YAP1 might occur independently of MST1/2. Nevertheless, genetic studies in mice showed that liver cells with LATS depletion were able to partially maintain their phospho-YAP1–S127 status52, suggesting that other kinases regulate YAP1 independently of LATS. Herein, we identified MST1 as a potent direct regulator of YAP1. Our data showed that MST1 might phosphorylate YAP1, possibly through LATS bypass mechanism in LNCaP or C4-2 PC cells; these cells naturally express very low or undetectable LATS protein or in which expression of LATS was depleted by siRNA. Notably, loss of LATS expression through DNA methylation was documented in PC47 and other cancers51. Altogether, MST1 and LATS sequentially or independently regulate YAP1 and these mechanisms, perhaps, occur in a context-dependent or cell-specific manner.

In addition, protein kinase B/AKT1 was suggested to phosphorylate YAP1 on S127 (ref. 57). Previously, our laboratory reported that MST1 functionally interacted with AKT1 (refs 52,58,59). In the current study, however, we did not examine the involvement of AKT1 in the regulation of YAP1 by MST1. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that AKT1 interferes YAP1 phosphorylation in LNCaP and C4-2 cells because these genetically-related cells express constitutively active AKT1 due to the loss of PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue)60; PTEN is a key negative regulator of PI-3-Kinase–AKT1 signalling61. However, our data revealed that YAP1 nuclear accumulation and its interaction with AR were significantly different in LNCaP and C4-2 with or without androgen exposure (Fig. 1d; Fig. 2). These differences appear to correlate with MST1 activity, but not with the activity of LATS or AKT1 (Fig. 1d; Figs 2–4). Besides, Jiang et al.44 identified additional phosphorylation sites (S163/164 and T63) on YAP1 in the lysate of LNCaP xenografts through a quantitative proteomic approach; however, that study did not show a change in phospho-YAP1–S127 levels. One possible explanation for it was that the MST1 kinase activity might be inactivated in LNCaP xenografts, possibly due to the expression of the constitutively active AKT1, which is known to inactivate MST1 via phosphorylation59. Thus, it would be interesting to know in a future investigation whether MST1 and LATS sequentially or independently regulate phosphorylation of S163/164 and T63 and whether these phosphorylation sites alter YAP1 nuclear localization and YAP1–AR interactions in the context of CRPC cells.

Lines of evidence have indicated that overexpression or nuclear accumulation of YAP1 may be associated with poor cancer prognosis23,40,62–65. Our data consistent with the literature have also suggested that nuclear YAP1 plays a critical role in the aetiology of CRPC by interacting with AR. Here we showed that androgen increased YAP1 nuclear localization and YAP1–AR interactions in CS LNCaP cells. Nevertheless, these molecular events cannot be reversed by androgen depletion in CR C4-2 cells, which express about 40–50% less MST1 than LNCaP48. Our laboratory previously reported that reduction or loss of MST1 might play a prominent role in PC progression48,52. Herein, we showed that loss of MST1 functions strongly correlated with increases in AI interactions of YAP1 and AR proteins in CRPC cells and that knockdown of MST1 in CS LNCaP cells promoted androgen-dependent and AI YAP1–AR interactions (Fig. 1e; Fig. 2b; Fig. 3f). The interaction between the two proteins is biologically relevant because YAP1 knockdown prevented AR-dependent gene expression and PC cell growth in vitro (Figs 5,6) and xenografts in vivo (Fig. 7). Nonetheless, future investigations are necessary to explore the underlying mechanism of how changes in YAP1 functionality alters the genome-wide AR–DNA interactions and the AR transcriptional programs relevant to metastatic CRPC.

Moreover, AR variants, lacking LBD and maintaining NTD and DBD, are implicated in the pathobiology of metastatic CRPC14. AR variants appear to be commonly observed in PC following androgen-deprivation therapy or exposure to anti-androgens14. Since antiandrogen therapy aimed at blocking ligand-dependent AR activity has limited clinical benefit, development of new therapies targeting AR–NTD may help to overcome this limitation. Herein, we showed that YAP1 interacted with both full length and naturally occurring truncated short AR forms independently of androgen exposure in CRPC cells (Fig. 2). In addition, YAP1 was identified as a key regulator of stem cell maintenance including cancer stem cells and EMT26. Mechanistically, cancer stem cell and EMT are believed to play a prominent role in metastatic CRPC. In addition, activation of YAP1 is implicated in the cellular response to DNA damage23,62,64,66 and resistance to chemotherapeutics40,65. YAP1 activation has also been shown to be an essential bypass mechanism in K-Ras-dependent tumours when K-Ras signalling is inhibited in pancreatic, colon and lung cancer26,56. In addition, overexpression of YAP1 has recently been reported to play a role in castration resistance67. Thus, blocking of the AR–YAP1 signalling axis may have important therapeutic implications in metastatic CRPC.

VP is an FDA-approved drug prescribed for age-related macular degeneration in photodynamic therapy (PDT)68. A study by Liu-Chittenden et al.51 showed that VP could bind the purified YAP1 protein and attenuate the interaction between YAP1 and TEAD in vitro, which correlated with suppression of YAP1-dependent liver cancer in mice51. Our study further clarified a mode of action of VP on YAP1. We showed that VP hindered YAP1 nuclear translocation by increasing its inhibitory S127 site phosphorylation by activating MST1. In addition, VP suppressed the growth of enzalutamide-resistant C4-2 cells that coincided with the inhibition of YAP1–AR interactions (Fig. 3). Ironically, AR-negative PC3 or DU-145 PC cells displayed resistance to VP induced growth retardation relative to AR positive LNCaP or C4-2 cells. Taken together, VP shows a great promise for the treatment of AR-dependent PC with the potentials of conferring enzalutamide resistance. Nonetheless, future investigations are warranted to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of VP in metastatic CRPC in preclinical and clinical settings. In summary, our data demonstrate that increases in nuclear YAP1 and AR interactions, possibly due to the loss of Hippo functions, may play a critical role in metastatic, lethal PC progression.

Methods

RNAi and plasmids

YAP1 siRNA (SMARTpool/On-TARGETplus, 10413), MST1 siRNA (SMARTpool, L-004157-00-0005), LATS1 siRNA (SMARTpool, L-004632-00-0005), LATS2 siRNA (SMARTpool, L-003865-00-0005) and scramble control (D-001810-10-05) were purchased from Dharmacon/Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Construction of tetracycline or doxycycline-inducible HA-tagged MST1 expression plasmid was described previously52. Briefly, PCR-amplified HA-tagged MST1-WT cDNA was inserted into the BamH1 and MluI enzyme sites in the pRetro-X-Pur vector (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) and the resulting plasmid was designated as pRXTP-HA-MST1. Gene specific siRNAs were transfected to cells using DharmaFect-2 or Lipofectamine RNAi MAX Reagent (13778-150, Life Technologies) in Opti-MEM medium (11058021, Life Technologies) according to manufacturer's instructions. Lentiviral pLKO1-shRNA YAP1#1 and pLKO1-shRNA YAP1#2 constructs were obtained from Addgene (27368/27369, http://www.addgene.org). PCR-amplified cDNA of the YAP1 fragment was cloned into the Not1 and EcoR1 restriction enzyme sites in the pGEX2 vector to generate GST–YAP1 (2–150 amino-acid residues), GST–YAP1 (151–296 residues), and GST–YAP1 (297–504 residues) deletion mutants. PCR amplified cDNA of the HA-tagged full-length (WT) AR or AR truncation mutant was cloned into the BamH1 and Xho1 restriction enzyme sites in the pcDNA3.1 vector to generate HA-ARWT, HA-AR-NTD (N-terminal domain: 2–555 residues) or HA-AR-DBD/LDB (DNA binding domain and ligand-binding domain) deletion mutant (556–919 residues). A QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used for a Ser 127 Ala mutation in the GST–YAP1 (2–150) fragment. High fidelity AccuPrime Pfx SuperMix (Invitrogen; Grand Island, NY) was used in PCR reactions. Standard molecular biology techniques were utilized for molecular cloning and plasmid amplification in DH5-α competent cells and plasmid purification. Fidelity and correct orientation of all expression constructs were verified by DNA sequencing before performing experiments. Supplementary Table 1 shows the primer sets used in molecular cloning.

GST–pull-down and in vitro kinase assays

The plasmid pGEX2-GST–YAP1–WT, -YAP1 (2–150), -YAP1 (151–296), or -YAP1 (297–504) or GST only was expressed in BL-21 bacteria in the presence of 1 mM IPTG for 4 h at 37 °C. Bacterially expressed GST only (control) or each GST–YAP1 mutant peptide was solubilized in NETN buffer (1% NP-40, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) and then purified by affinity chromatography on glutathione–sepharose beads (GE Healthcare; Piscataway, NJ) and stored in PBS at +4 °C until use. For GST–pull-down assays, recombinant and purified GST control or GST–YAP1 mutant peptides were mixed with total lysates isolated from LNCaP cells, which were obtained from American Type Culture Collection, grown in serum-fed condition and then incubated 2 h at 4 °C for constant rotation. The lysates from LNCaP cells were used as a source of AR. After extensive washing of unbound proteins, bound protein eluted and analysed by 8% sodium dodecyl–PAGE (SDS–PAGE). Coomassie blue staining visualized the GST only or GST–YAP1 fusion peptides. Western blots were employed to visualize the bound AR. In vitro kinase assay was performed as described previously52. Briefly, GST only, GST–YAP1 (2–150)–S127 wild–type and GST–YAP1 (2–150)–S127A mutant fusion peptides were used as substrates to perform the non-radioactive kinase assays using the pre-activated, recombinant, full length, human MST1 protein kinase (Millipore, 14–624).

Cell engineering and cell viability assays

Lentivirus carrying control shRNA or YAP1 shRNA expression construct in combination with pCMV–VSV-G and pCMV-dR8.2 dvpr packaging plasmids were transfected into HEK-293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen) and as described52. Lentiviral particles were collected at 48 h post transfection and stored at 80 °C until use. For stable cell engineering, 3 × 105 C4-2 cells grown in six-well plates were infected with lentiviral particles carrying control shRNA or YAP1 shRNA. Puromycin (1 μg ml −1) resistant shRNA control or shRNA YAP1 cells were selected and amplified for the future biological assays. Stable control shRNA or YAP1 shRNA C4-2 cells were also engineered to express luciferase reporter for animal experiments. Cell viability was assessed in 96-well culture dish under varying conditions utilizing a MTS CellTiter 96 AQueous assay system according to the manufacturer's instruction (Promega; Madison, WI) and as described59.

Luciferase reporter assays

Mock vector, YAP1–WT, YAP1-ΔN or YAP1-ΔC plasmid and p61-Luc reporter (6.1 kb of prostate-specific antigen promoter liked to luciferase reporter gene; p61-Luc) were transiently transfected into LNCaP cells. Cells were treated with EtOH (vehicle) or 10 nM dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in charcoal-stripped serum (CSS) conditions. Luciferase reporter assays were performed using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Relative light units were detected using BMG Labtech microplate reader (Cary, NC) as described59 and normalized to total proteins.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

LNCaP or C4-2 cells were treated with EtOH (vehicle) 10 nM DHT in CSS or treated with DMSO or Verteporfin (VP; Cat#SML0534; Sigma-Aldrich) in serum-fed condition for 24 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Permeabilized cells were incubated with anti-YAP1 (8418, Cell Signalling, Denver, USA, 1:50) and anti-AR (554225, BD Pharmingen, CA, USA, 1:100) antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated anti-mouse IgG and Cy3 conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000 dilution) was used to detect AR or YAP1 signals, respectively. Immunofluorescence analysis of HA-MST1 expression was conducted according to a published study52. Slides were mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Labs, H-1200). Images were captured by confocal microscopy (Leica SP5-X, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed on 5-micron thick formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections. All experiments involving human subjects were conducted according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the West Los Angeles VA Hospital and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Informed consent was not required because all samples were deidentified and archived. Clinical samples consisting of benign prostate and prostate cancer cases were used to visualize YAP1 protein expression. In addition, tissue sections from prostate tumour xenografts were used to detect AR, YAP1, Ki-67, or cleaved-caspase3 (c-Cas3) expression. Briefly, tissue slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated using standard techniques. After antigen retrieval and blocking, slides were incubated with anti-AR (5153, Cell Signaling, 1:100), anti-YAP1 (NBP2-22117SS, Novus Biologicals, 1:100, anti-Ki67 (ab16667, Abcam, 1:200) and anti-c-Cas3 (9661, Cell Signaling, 1:300) primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. Signals were detected by substrate hydrogen peroxide using diaminobenzidine chromogen and counterstained by haematoxylin. Slides were then dehydrated and mounted. IHC experiments were conducted according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dako Corporation; Carpinteria, CA).

Protein analysis

Total proteins were extracted from LNCaP or C4-2 cells and from fresh-frozen tissues of human prostate clinical samples or tumor xenografts in ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors). Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were isolated using a nuclear extraction kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Affymetrix; Santa Clara, CA) with modifications52,59. Co-IP was performed with anti-YAP1 or anti-MST1 antibody at 4 °C as described previously69. The immune complexes were collected with Protein A-Sepharose conjugate (GE Healthcare) and washed in lysis buffer. Bound proteins were analysed by 8% SDS–PAGE and WBs. Membranes were blocked with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% (w/v) skim milk, followed by incubation with anti-YAP1 (Cat#8418, Cell Signaling, 1:1,000), anti-phospho-YAP1–S127 (Cat#4911, Cell Signaling, 1:1,000), anti-MST1 (Cat#3682, Cell Signaling, 1:1,000), anti-phosho-MST1-T183 (Cat#3681, Cell Signaling, 1:1,000), anti-AR (Cat#06-680, Millipore, 1: 1,000), anti-HA (Cat#3724, Cell Signaling, 1:1,000), anti-Lamin A/C (Cat#2032, Cell Signaling, 1:1,000), anti-PSA (Cat#sc-7638, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1,000) or anti-b-Actin (Cat#A2228, Sigma, 1:5,000), anti-LATS1 (Cat#A300-487A-T, Bethyl Laboratories, 1:500) and LATS2 antibody (Cat#A300-479-T, Bethyl Laboratories, 1:500) antibody. Signals were detected using a SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescence Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Roxford, IL). Where applicable, signal intensities were quantified by ImageJ densitometry analysis software (version 1.46r).

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR

Total RNA from cells or tumor xenografts were extracted suing RNeasy RNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen; Maryland, MA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using total RNA (2 μg per reaction) with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase and oligo (dT)-12 primers (Invitrogen; Grand Island, NY). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Invitrogen) and Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies). RNA expression changes were determined using a 2-ΔCt method70. GAPDH mRNA was used as an internal control in all qPCR reactions. Supplementary Table 1 shows the qPCR primers used for YAP1, KLK3, PSMA, FKBP5, TMPRSS2 and GAPDH mRNA amplifications.

Cell cycle analysis and apoptosis assays

Cells were treated either with DMSO (vehicle) or Verteporfin (SML0534; Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 h in serum-fed conditions. Cells were fixed in 0.5% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at 4 °C, washed with PBS, and then permeabilized in 70% cold EtOH for 1 h at 4 °C. Cells were washed with cold PBS and 1 × binding buffer containing 50 μl of propidium iodide (PI) staining solution (Cat#00-6990, eBioscience,) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Cells were filtered through a 0.45-μm filter and analysed by flow cytometry (CyAn ADP Analyzer, Beckman Coulter). For Annexin V staining, an Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit APC (Cat#88-8007, eBioscience,) was used. Briefly, cells were incubated with APC-conjugated Annexin V for 15 min at room temperature, washed with binding buffer, and then incubated with PI Staining Solution for 3 h at 4 °C and kept in the dark until analysis.

Sphere formation assays

Sphere formation assays were performed as described59. Briefly, control shRNA and YAP1 shRNA cells (500 cells per well) suspended in 100 μl ice-cold Matrigel in RPMI medium (1:1 ratio) were overlaid onto the presolidified 50% Matrigel in 24-well plates (100 μl per well). Cells were fed with 500 μl RPMI medium containing 10% FBS and grown for 14 days with a change of medium every 3 days. For the VP study, C4-2 cells (500 cells/well) were grown on Matrigel and treated either with DMSO (vehicle) or VP in serum-fed conditions for 14 days. Spheres were imaged and then manually quantified.

Invasion assays

Control shRNA or YAP1 shRNA cells (1 × 105 cells per well) were seeded in a 24-well Boyden chamber with an 8-μm filter coated with 20% growth factor reduced Matrigel. Cells were grown in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS for 16, 24 and 48 h in a 37 °C cell culture incubator supplemented with 5% CO2. Cells in the inner side of the chamber were gently removed by scraping with a wet cotton swab. Invaded cells at the outer side of the chamber were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and rinsed twice with PBS. Cells were stained with 0.5% Crystal Violet for 20 min at room temperature and then rinsed with tap water to remove excess dye. Five random fields of stained cells were imaged using bright field microscopy at 20× magnification and average cell numbers per field were plotted as a function of time.

Animal experiments

Xenograft experiments in mice were conducted as previously described52 and according to a protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Briefly, shRNA control or shRNA YAP1 C4-2 cells (1 × 106 cells per well) mixed with Matrigel (1:1 ratio in 100 μl volume) were injected subcutaneously in the right and left flanks of the hormonally intact, four-week old (approximately 25 g), immune deficient (SCID), male mice (Charles River, Boston, MA). Tumour growth was monitored weekly by luciferase imaging in live animals for up to 5 weeks. Luciferin substrate (100 μl volume) was injected into mice via intraperitoneal (i.p.) route and mice were then imaged at 8–10 min post luciferin injection using Xenogen IVIS Spectrum Optical In Vivo High Resolution Bioluminescence Imaging System. Photons were counted and plotted as a function of time. Animals were sacrificed humanely and tumours were collected for morphological and molecular analysis. At 5 weeks, tumour volumes were also measured and plotted.

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as mean of ±s.d. A paired-end Student's t-test was employed to determine statistical significance between control and test groups. Values of P≤0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Leland Chung and Michael Freeman for critically evaluating the data, Qiang Wang for providing YAP1 expression vector, Rosalyn Adam for cell lines and Gina Chia-Yi Chu for helping primer orders. This study was partly supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant UL1TR000124 (CSMC/UCLA) pilot project V040 (BC), The Jesse and Donna Garber Foundation (BC), and The Jean Perkins Foundation (IG), and The Uro-Oncology Program at Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Author contributions

G.K.-A. designed and performed the experiments, collected and analysed the data, helped in constructing the figures and wrote the manuscript. A.A. performed the experiments, collected the data and help constructed figures. M.L. and I.G. helped performed and analyse the IHC data. B.C. designed and performed the experiments, collected and analysed the data, constructed figures and wrote and submitted manuscript for publication.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at http://www.nature.com/naturecommunications

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

How to cite this article: Kuser-Abali, G. et al. YAP1 and AR interactions contribute to the switch from androgen-dependent to castration-resistant growth in prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 6:8126 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9126 (2015).

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scher HI, Sawyers CL. Biology of progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: directed therapies targeting the androgen-receptor signaling axis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:8253–8261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohler JL. Castration-recurrent prostate cancer is not androgen-independent. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2008;617:223–234. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69080-3_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waltering KK, Urbanucci A, Visakorpi T. Androgen receptor (AR) aberrations in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012;360:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooke GN, Bevan CL. The role of androgen receptor mutations in prostate cancer progression. Curr. Genomics. 2009;10:18–25. doi: 10.2174/138920209787581307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CD, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat. Med. 2004;10:33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulholland DJ, et al. Pten loss and RAS/MAPK activation cooperate to promote EMT and metastasis initiated from prostate cancer stem/progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1878–1889. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culig Z, Santer FR. Androgen receptor co-activators in the regulation of cellular events in prostate cancer. World J. Urol. 2012;30:297–302. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0797-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishizaki F, et al. Androgen deprivation promotes intratumoral synthesis of dihydrotestosterone from androgen metabolites in prostate cancer. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1528. doi: 10.1038/srep01528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang KH, et al. A gain-of-function mutation in DHT synthesis in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cell. 2013;154:1074–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu K, et al. EZH2 oncogenic activity in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells is Polycomb-independent. Science. 2012;338:1465–1469. doi: 10.1126/science.1227604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang KH, et al. Dihydrotestosterone synthesis bypasses testosterone to drive castration-resistant prostate cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:13728–13733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107898108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai C, et al. Intratumoral de novo steroid synthesis activates androgen receptor in castration-resistant prostate cancer and is upregulated by treatment with CYP17A1 inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6503–6513. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antonarakis ES, et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N Eng J. Med. 2014;371:1028–1038. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griekspoor A, Zwart W, Neefjes J, Michalides R. Visualizing the action of steroid hormone receptors in living cells. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 2007;5:e003. doi: 10.1621/nrs.05003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chmelar R, Buchanan G, Need EF, Tilley W, Greenberg NM. Androgen receptor coregulators and their involvement in the development and progression of prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;120:719–733. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen S, Kesler CT, Paschal BM, Balk SP. Androgen receptor phosphorylation and activity are regulated by an association with protein phosphatase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:25576–25584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.043133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanaja DK, Mitchell SH, Toft DO, Young CY. Effect of geldanamycin on androgen receptor function and stability. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2002;7:55–64. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2002)007<0055:eogoar>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2001;1:34–45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agoulnik IU, Weigel NL. Coactivator selective regulation of androgen receptor activity. Steroids. 2009;74:669–674. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan X, Balk SP. Mechanisms mediating androgen receptor reactivation after castration. Urol Oncol. 2009;27:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang K, Degerny C, Xu M, Yang XJ. YAP, TAZ, and Yorkie: a conserved family of signal-responsive transcriptional coregulators in animal development and human disease. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009;87:77–91. doi: 10.1139/O08-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy D, Adamovich Y, Reuven N, Shaul Y. Yap1 phosphorylation by c-Abl is a critical step in selective activation of proapoptotic genes in response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. 2008;29:350–361. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lian I, et al. The role of YAP transcription coactivator in regulating stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1106–1118. doi: 10.1101/gad.1903310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camargo FD, et al. YAP1 increases organ size and expands undifferentiated progenitor cells. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:2054–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shao DD, et al. KRAS and YAP1 Converge to Regulate EMT and Tumor Survival. Cell. 2014;158:171–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J, et al. YAP-dependent induction of amphiregulin identifies a non-cell-autonomous component of the Hippo pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:1444–1450. doi: 10.1038/ncb1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu MZ, et al. AXL receptor kinase is a mediator of YAP-dependent oncogenic functions in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2011;30:1229–1240. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang P, et al. PP1A-mediated dephosphorylation positively regulates YAP2 activity. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Yes-associated protein (YAP) transcriptional coactivator functions in balancing growth and differentiation in skin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:2270–2275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019603108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao B, et al. TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1962–1971. doi: 10.1101/gad.1664408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrigno O, et al. Yes-associated protein (YAP65) interacts with Smad7 and potentiates its inhibitory activity against TGF-beta/Smad signaling. Oncogene. 2002;21:4879–4884. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenbluh J, et al. beta-Catenin-driven cancers require a YAP1 transcriptional complex for survival and tumorigenesis. Cell. 2012;151:1457–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao B, et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2747–2761. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu CM, et al. Mst1 overexpression inhibited the growth of human non-small cell lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013;20:453–460. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2013.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konsavage WM, Jr., Kyler SL, Rennoll SA, Jin G, Yochum GS. Wnt/ beta-catenin signaling regulates Yes-associated protein (YAP) gene expression in colorectal carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:11730–11739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinhardt AA, et al. Expression of Yes-associated protein in common solid tumors. Hum. Pathol. 2008;39:1582–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ge L, et al. Yes-associated protein expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma nodal metastasis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou D, et al. Mst1 and Mst2 maintain hepatocyte quiescence and suppress hepatocellular carcinoma development through inactivation of the Yap1 oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:425–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang C, et al. Differences in Yes-associated protein and mRNA levels in regenerating liver and hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2012;5:410–414. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Striedinger K, et al. The neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, regulates human meningioma cell growth by signaling through YAP. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1204–1212. doi: 10.1593/neo.08642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee SE, et al. RAF kinase inhibitor-independent constitutive activation of Yes-associated protein 1 promotes tumor progression in thyroid cancer. Oncogenesis. 2013;2:e55. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2013.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang W, et al. Yes-associated protein 1 exhibits oncogenic property in gastric cancer and its nuclear accumulation associates with poor prognosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:2130–2139. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang N, et al. In vivo quantitative phosphoproteomic profiling identifies novel regulators of castration-resistant prostate cancer growth. Oncogene. 2014;34:2764–2776. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thalmann GN, et al. Androgen-independent cancer progression and bone metastasis in the LNCaP model of human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2577–2581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ni L, et al. Androgen induces a switch from cytoplasmic retention to nuclear import of the androgen receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013;33:4766–4778. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00647-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scher HI, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N. Eng. J. Med. 2012;367:1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuser-Abali G, Alptekin A, Cinar B. Overexpression of MYC and EZH2 cooperates to epigenetically silence MST1 expression. Epigenetics. 2014;9:634. doi: 10.4161/epi.27957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila Mst ortholog, hippo, restricts growth and cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Cell. 2003;114:457–467. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00557-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Powzaniuk M, et al. The LATS2/KPM tumor suppressor is a negative regulator of the androgen receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004;18:2011–2023. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu-Chittenden Y, et al. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1300–1305. doi: 10.1101/gad.192856.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cinar B, et al. MST1 is a multifunctional caspase-independent inhibitor of androgenic signaling. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4303–4313. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao B, Li L, Lei Q, Guan KL. The Hippo-YAP pathway in organ size control and tumorigenesis: an updated version. Genes Dev. 2010;24:862–874. doi: 10.1101/gad.1909210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pan D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu FX, et al. Protein kinase A activates the Hippo pathway to modulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1223–1232. doi: 10.1101/gad.219402.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kapoor A, et al. Yap1 activation enables bypass of oncogenic kras addiction in pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2014;158:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Basu S, Totty NF, Irwin MS, Sudol M, Downward J. Akt phosphorylates the Yes-associated protein, YAP, to induce interaction with 14-3-3 and attenuation of p73-mediated apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:11–23. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00776-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cinar B, et al. The pro-apoptotic kinase Mst1 and its caspase cleavage products are direct inhibitors of Akt1. EMBO J. 2007;26:4523–4534. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Collak FK, Yagiz K, Luthringer DJ, Erkaya B, Cinar B. Threonine-120 phosphorylation regulated by phosphoinositide-3-kinase/akt and Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway signaling limits the antitumor activity of Mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:23698–23709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.358713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davies MA, et al. Regulation of Akt/PKB activity, cellular growth, and apoptosis in prostate carcinoma cells by MMAC/PTEN. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2551–2556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee SH, et al. A constitutively activated form of the p110beta isoform of PI3-kinase induces prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005642107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fernandez LA, et al. Oncogenic YAP promotes radioresistance and genomic instability in medulloblastoma through IGF2-mediated Akt activation. Oncogene. 2012;31:1923–1937. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Strano S, et al. The transcriptional coactivator Yes-associated protein drives p73 gene-target specificity in response to DNA Damage. Mol. Cell. 2005;18:447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lapi E, et al. PML, YAP, and p73 are components of a proapoptotic autoregulatory feedback loop. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang M, et al. Inactivation of YAP1 enhances sensitivity of the yeast RNR3-lacZ genotoxicity testing system to a broad range of DNA-damaging agents. Toxicol. Sci. 2011;120:310–321. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Strano S, et al. The transcriptional coactivator Yes-associated protein drives p73 gene-target specificity in response to DNA Damage. Mol. Cell. 2005;18:447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang L, et al. The Hippo Pathway Effector YAP Regulates Motility, Invasion, and Castration-Resistant Growth of Prostate Cancer Cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015;35:1350–1362. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00102-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kaiser PK, et al. Ranibizumab for predominantly classic neovascular age-related macular degeneration: subgroup analysis of first-year ANCHOR results. Am. J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cordenonsi M, et al. The Hippo transducer TAZ confers cancer stem cell-related traits on breast cancer cells. Cell. 2011;147:759–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.