Graphical abstract

Keywords: Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, Systemic lupus erythematosus, Rheumatoid arthritis, Arthralgias, Breast cancer, Aromatase inhibitors

Abstract

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is characterized by particular cutaneous manifestations such as non-scaring plaques mainly in sunlight exposed parts of the body along with specific serum autoantibodies (i.e. antinuclear antibodies (ANA), Ro/SSa, La/SSb). It is considered either idiopathic or drug induced. The role of chemotherapeutic agents in causing SCLE has been investigated with the taxanes being the most common anticancer agents. However, recent data emerging point toward antiestrogen therapies as a causative factor not only for SCLE but also for a variety of autoimmune disorders. This is a report of a case of a 42 year old woman who developed clinical manifestations of SCLE after letrozole treatment in whom remission of the cutaneous manifestations was noticed upon discontinuation of the drug. In addition, an extensive review of the English literature has been performed regarding the association of antiestrogen therapy with autoimmune disorders. In conclusion, Oncologists should be aware of the potential development of autoimmune reactions in breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors.

Introduction

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) (i.e. letrozole, anastrozole, exemestane) are used in the treatment of hormone dependent breast cancer. Their use may be complicated with cutaneous events such as increased sweating, alopecia, dry skin, pruritus, and urticaria, but also with a variety of rashes. The eruption of SCLE may begin with papules, which either coalesce or develop into annular erythematous lesions with slight scale or into scaly psoriasiform lesions. In rare cases angioedema, toxic epidermal necrolysis and erythema multiforme may be observed [1], [2]. To date, there have been a number of reports of SCLE attributed to the use of antiestrogen therapy [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. In addition, some chemotherapeutic agents have already been reported to induce SCLE, including cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, bevacizumab, fluorouracil or capecitabine with most prevalent the use of taxanes [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. However, the accurate mechanism of SLE phenomena and various autoimmune disorders caused by antiestrogen therapy remains to be elucidated. In this article a patient with breast cancer treated with letrozole who developed SCLE is reported. An extensive search of the literature regarding the association between endocrine treatment and SCLE or autoimmune disorder development, was also attempted.

Material and methods

All published papers were obtained through the PubMed database, using the subsequent Medical Subject Heading terms: “autoimmunity AND cancer”, “autoimmune manifestations AND endocrine treatment AND breast cancer”, “aromatase inhibitors AND autoimmune diseases”, “lupus erythermatosus AND aromatase inhibitors”. Furthermore, a manual search and review of reference lists were carried out. Titles were screened and studies were excluded if obviously irrelevant. Literature up to December 31, 2015 was included.

Case presentation

A 42 year old Caucasian woman with a past medical history of heterozygous beta-thalassemia, photosensitivity and a family history of a mother with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), was diagnosed in December 2011 with metastatic breast cancer (estrogen receptor positive, progesterone receptor negative and HER2 positive). She was first presented with anemia and thrombocytopenia and the diagnosis was established following a bone marrow biopsy which revealed a metastatic adenocarcinoma compatible with breast cancer. She was treated with paclitaxel, trastuzumab and zoledronic acid till April 2012 with a significant improvement of her hematologic indices. Since then she continued with trastuzumab, tamoxifen, and zoledronic acid until July 2014 when progressive disease in the abdomen, brain and lungs was confirmed. Whole brain radiotherapy was provided and a second line chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel was administered until early December 2014. Partial remission in the abdomen and complete response in the chest were found, while brain metastases remained stable. She then went on letrozole, luteinizing hormone – releasing hormone (LHRH) analog and trastuzumab.

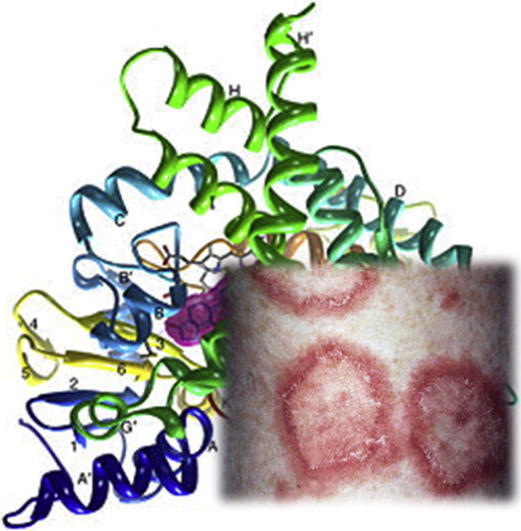

Within the first weeks and after the initiation of hormonal treatment, on late December 2014, an annular erythematous psoriasiform rash in the arms was noticed. During her next visits and being on the same treatment the rash deteriorated necessitating local and systematic corticosteroids. In June 2015 due to hematologic progression treatment was altered to the combination of trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and docetaxel with discontinuation of letrozole. A month later the patient was admitted to the oncology ward due to febrile neutropenia following treatment. At the time of her admission while she was kept on corticosteroids the skin rash was still persisting (Fig. 1). A skin tissue biopsy was performed revealing non-specific interface dermatitis. No vasculitis was noticed. A rheumatology consultation along with elevated serum ANA (1/640), Ro52 and Ro60 titers established the diagnosis of SCLE. The patient was then prescribed hydroxychloroquine along with a gradual tapering of the corticosteroids. She continued her medication until October 2015 when she visited the outpatient clinic. A full remission of the rash was then established and the patient had normal values on her complete blood count. A total body computed tomography (CT) was scheduled in order to further evaluate her disease and decide on her further antitumor treatment (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Rash diagnosed as subacute lupus erythematosus in a patient with metastatic breast cancer treated with letrozole.

Table 1.

Time course of reported patient since diagnosis of breast cancer.

| Date | Fact |

|---|---|

| December 2011 | Breast cancer diagnosis |

| December 2011–April 2012 | Paclitaxel, Trastuzumab |

| April 2012–July 2014 | Tamoxifen, Trastuzumab |

| July 2014–December 2014 | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Trastuzumab |

| Early December 2014 | Letrozole, LHRH, Trastuzumab |

| Late December 2014 | Appearance of rash |

| January 2015–April 2015 | Deterioration of rash |

| May 2015 | Onset of corticosteroids |

| June 2015 | Anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, persistence of rash |

| June 2015 | Letrozole discontinuation, SCLE diagnosis and hydroxychloroquine initiation with corticosteroid tapering |

| October 2015 | Full remission of SCLE manifestations |

Discussion

The major morphological characteristics of SCLE are annular, non-scarring, papulosquamous or psoriasiform plaques with distribution mainly to the sunlight exposed areas of the body [13]. The autoimmune profile of SCLE may consist of positive Ro/SSA or La/SSB antibody titles while most patients test positive for antinuclear antibodies (ANA) [14]. Complete blood count tests may reveal anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia while skin tissue biopsy indicates perivascular and subepidermal inflammatory cell infiltration or vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer. Constitutional symptoms such as malaise, fever and arthralgias may be present [8]. The diagnosis is confirmed with the conjunction of both clinical and serological profiles, while full picture of SLE may be absent. The treatment consists of therapy with corticosteroids both systematic and locally while in some cases specific drugs such as hydroxychloroquine may be prescribed depending on the severity of the manifestations. In the case of drug induced SCLE the clinical features and laboratory findings do not differentiate from typical subacute SLE [15]. Consequently, drug-induced SCLE must be of high suspicion when typical findings of SCLE onset correlate with the induction of a new drug. A mandatory discontinuation of the new drug should be considered [16].

Throughout the literature drug induced SCLE has been described and associated with the use of thiazide diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and taxanes, and most recently with antiestrogen therapy [9], [13], [17]. The use of tamoxifen in three patients and anastrozole in one patient resulted in the appearance of SCLE [3], [5]. There are also two cases in the current literature reporting the association between aminoglutethimide and SLE in cancer patients [6], [7]. Etherington et al. reported a breast cancer case with a history of SLE who presented with a flair of a lupus-like syndrome and subsequent remission of her symptoms after switching her treatment from tamoxifen to aminoglutethimide [7] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cases of antiestrogen therapy associated SCLE or SLE.

| Author | Hormonal treatment | Patient age | Type of malignancy | Clinical findings | Time of manifestations onset | Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrew et al. [4] | Tamoxifen | 40 y old female | Breast cancer | Facial eruption | Four months after initiation of tamoxifen | Discontinuation of TMX |

| Fumal et al. [3] | Tamoxifen | 68 y old female | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Erythematosus rash arms, lower neck | Six years after initiation of tamoxifen | Discontinuation of TMX |

| Fumal et al. [3] | Tamoxifen | 84 y old female | Breast cancer | Annular, widespread erythematous rash | Four years after initiation of tamoxifen | Discontinuation of TMX |

| Trancart et al. [5] | Anastrazole | 73 y old female | Breast cancer | Intense annular cutaneous eruption upper trunk, face, neck | One month after initiation of anastrozole | Discontinuation of anastrozole, corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine |

| McCraken et al. [6] | Aminoglutethimide | 57 y old female | Breast cancer | Soft tissue swelling, severe aching in muscles | Six months after initiation of aminoglutethimide | Discontinuation of aminoglutethimide |

| Etherington et al. [7] | Tamoxifen and Aminoglutethimide | 77 y old female | Breast cancer | Generalized joint pains, hair fall, Raynaud phenomenon | Eight years after initiation of tamoxifen | Corticosteroids and aminoglutethimide continuation |

It must be pointed out that breast cancer itself may induce the appearance of both serum autoantibodies and of clinical manifestations of autoimmune paraneoplastic syndromes [18]. The onset of the cutaneous presentations correlates with the onset of malignancy and sometimes even before the tumor is diagnosed. Complete remission of the skin manifestations can be seen following successful treatment of the underlying malignant disease [18], [19], [20].

The relationship between estrogens and rheumatic diseases has been widely investigated. There have been a number of studies showing that estrogens induce and androgens suppress the phenomena of SLE-like disease in F1 and MRL/I pr mice [21]. In addition, it has been proven that sex hormones have an immunomodulatory role in rheumatic diseases [22]. Other reports have also demonstrated that estrogens induced the production of anti-dsDNA antibodies by circulating lymphocytes in patients with active SLE and that antiestrogen therapy, in particular tamoxifen, resulted in the reduction of IgG3 autoantibodies in the sera of (NZB × NZW)F1 female mice ameliorating the course of SLE-like disease [21], [23].

On the other hand, it seems that when circulating estrogen levels are higher they can inhibit the function of neutrophils. The use of AIs results in reduction of estrogen levels which in turn, increases the function of neutrophils. The cells then adhere to the blood vessel endothelium and provoke autoimmune vasculitis or vasculitis-like reactions [24], [25]. To date there have been reports of cutaneous vasculitis attributed to the use of exemestane in three patients [1], while the use of letrozole seems to have been responsible for inducing necrotizing leukocytoclastic small vessel vasculitis in a number of cases [25], [26], [27]. However as Digklia et al. have reported the case of leukocytoclastic vasculitis that was attributed to the use of letrozole in a patient, did not recur when switch to exemestane took place. Thus it would be reasonable to speculate that idiosyncratic reaction of the patient rather than estrogen depletion may have induced the onset of vasculitis [26]. In addition, anastrozole was associated with the onset of pruritic micropapular eruptions in a single case and cutaneous vasculitis has also been attributed to the same medication in other patients [27], [2], [28] (Table 3).

Table 3.

|

Furthermore, the association between rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and the use of antiestrogen therapy has also been investigated. There are case reports of rheumatoid arthritis induction with the use of exemestane as well as accelerated cutaneous nodulosis in a patient already diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis undergoing letrozole therapy [29], [30], [31]. Chen and Ballou have recently reported that the use of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in women with breast cancer diagnosis results in higher incidents of both SLE and RA. The use of SERMS resulted in a statistically significant risk of SLE and RA, while the use of AIs mainly resulted in higher incidents of RA. On the contrary, the same report comes to the conclusion that the use of AIs tends to decrease the incidence of SLE although those results were not statistically significant [32]. Furthermore, third generation AIs suppress the differentiation of naïve T-cells to regulatory T-cells with a concomitant increase in proinflammatory cytokines interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-12 (IL-12). Specifically, anastrozole treatment was associated with an increased expression of genes responsible for inflammatory processes in hormone receptor positive breast cancer. In addition, the use of SERMs has been associated with a reduction in the maturation and activity of autoreactive B cells and immunostimulatory dendritic cells which in turn results in alleviation of dermatomyositis symptoms [33].

The immunomodulatory function of AIs has also been reported as a potential causative mechanism leading to arthralgias and arthritis like syndromes [34]. Aminoglutethimide can result in increased natural killer (NK) cell activation whereas the use of formestane, a second generation AI, causes elevation of IL-2 and INF-γ levels. Reports of lymphocyte count reduction in patients being on exemestane, a steroidal AI, and a blockage in the balance of IgG2a/IgG1 have been described [33]. Consequently, apart from the aforementioned correlation between the use of aromatase inhibitors and SLE or SLE-like syndromes, the use of AI has been associated with the induction of arthralgias. Women on this type of antiestrogen therapy often come up with symmetrical joint pains, morning stiffness which resolves with exercise, mainly of the wrists but also in other joints of the body. Carpal tunnel syndrome is also a notable manifestation while on AI. These symptoms can lead to discontinuation of the AI therapy in a significant proportion of the patients [35], [36]. Their relationship with immune disorders such as sicca syndrome, systemic sclerosis and Sjogren syndrome has also been investigated with the latter being more prevalent as reported by Laroche et al. Among twenty-four women investigated for joint pain, nineteen were found to have inflammatory pain of the joints and two had inflammatory laboratory profile. Ten patients were diagnosed with sicca syndrome of the eyes or mouth, one was diagnosed with Sjogren syndrome, one RA, and another Hashimoto thyroiditis and seven more were considered to have probable Sjogren syndrome [37], [38].

Many theories have been proposed in order to explain the mechanism leading to arthritis manifestations such as the nociceptive role of estrogens and the subsequent increased sensitivity to pain stimuli following antiestrogen therapy [39]. The increased activation of vitamin D receptor attributable to antiestrogens leads to decline of vitamin D levels causing arthralgias [40]. However, the immunomodulatory theory remains a plausible explanation. It seems that the aforementioned increased plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines have a significant role in the induction of arthritis or arthritis like syndromes. Furthermore, evidence exists concerning the expression of aromatase in synovial cells which is then inhibited by the use of AI thus resulting in high intrasynovial levels of IL-6 leading to inflammation of the joints. In addition, the upregulation of RANK ligand on osteoblasts induces the function of osteoclasts causing bone desorption. In one study, women on immunotherapy with thymosin a1, as a part of their arthralgia therapy, have been reported to measure lower serum levels of INF-γ, thus experiencing alleviation of their symptoms [41]. Furthermore recent data concerning muscoskeletal pain induced by the use of AIs have emerged. Hershman et al. have concluded that the use of omega-3 fatty acids which were speculated to have an anti-inflammatory role failed to improve the patients symptoms above placebo. The use of omega-3 fatty acids in women suffering from arthralgias while on AIs resulted in decreased triglyceride levels while there was no difference in symptoms alleviated by the use of omega-3 fatty acids or placebo [42]. Finally, the correlation between autoimmune manifestations and AIs extends even to the induction of autoimmune hepatitis. Throughout the literature there are two case reports of female patients who developed autoimmune hepatitis with positive serum screening profile and compatible liver biopsy findings after the initiation of anastrozole for their breast cancer [43], [44]. Recent data suggest a tight correlation of drug induced cutaneous lupus erythematosus with immunogenic predisposing of the patient HLA subtype. Most cases of drug induced lupus typically occur in patients with history of personal or family photosensitivity and it has been demonstrated that most of the culprit drugs usually cause photosensitivity reactions [45].

Conclusions

To our knowledge, there is a conflict regarding the use of AIs and subsequent SCLE or SLE prevalence. So far, some data suggest that antiestrogen therapy may have beneficial effects in patients with SLE, while there are studies showing increased incidence of rheumatic diseases with the use of both SERMS and AIs [33]. Consequently, more research should be conducted in order to elucidate the autoimmune adverse effects induced by hormonal agents in patients with breast cancer. Finally, clinicians must be alert of the correlation between endocrine therapy and the wide spectrum of rheumatic disorders.

This patient, who has been under surveillance and treatment since 2011, underwent sequential therapies with taxane consisting agents, anti-HER2 agents, platinum analogs, bisphosphonates without any skin disorders. As soon as letrozole was initiated, a distinct skin entity emerged which did not completely disappear despite treatment with corticosteroids. Skin rash disappeared only when letrozole was discontinued. In addition, past medical and family history of this patient must be taken into consideration regarding previous photosensitivity and mother’s SLE diagnosis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

.

Biographies

George Zarkavelis is a Fellow in Medical Oncology, Department of Medical Oncology, Ioannina University Hospital, Greece.

Aristomenes Kollas is a Fellow in Medical Oncology, Department of Medical Oncology, Ioannina University Hospital, Greece.

Eleftherios Kampletsas is a Senior Oncologist, Department of Medical Oncology, Ioannina University Hospital, Greece.

Vasilis Vasiliou is a Fellow in Dermatology, Department of Dermatology, Ioannina University Hospital, Greece.

Kaltsonoudis Evripidis MD, PhD is a Registrar of Rheumatology, Rheumatology Clinic, Department of Internal Medicine University Hospital of Ioannina.

Alexandros A. Drosos is a Professor of Medicine/Rheumatology, Head of Rheumatology Clinic Department of Internal Medicine, Medical School, University of Ioannina 45110, Ioannina, Greece.

Hussein Khaled is a Professor of Medical Oncology at the National Cancer Institute of Cairo University. He was the former minister of higher education of Egypt (2012), former vice president of Cairo University for post graduate studies and research (2008–2011), and the former dean of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute (2002–2008). He has many national, regional, and international activities. Some of his national activities include being the secretary general of the Egyptian Foundation for Cancer Research, the head of the council of the Egyptian medical oncology fellowship, the head of the committee of oncology university staff promotion, and the Editor in-Chief of the Journal of Advanced Research, the official journal of Cairo University. Regionally he was the assistant secretary general of the Arab Medical Association Against Cancer for 4 years, the national representative of the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) for Egypt and North Africa for 6 years (2000–2006), and the current president of the South and East Mediterranean College of Oncology. On the International level, he is a member of many international societies including the ESMO, ASCO, INCTR, and a member of the lymphoma group in the EORTC. He was also a member of the editorial board of the Annals of Oncology, the ESMO official journal (2006–2012). His research activities are focused mainly on bladder cancer (both biologic and clinical aspects), breast cancer, and malignant lymphomas, with more than 150 national and international publications (total impact factor of 253.387, total citations of 1388, and h-index of 20).

Nicholas Pavlidis is a Professor and Head of the Department of Medical Oncology, Ioannina University Hospital, Greece, Member of Scientific Committee and Coordinator of Master classes of European School of Oncology, Member of Scientific Committee of ESMO/ASCO Global Curriculum, and Editor in Chief, Cancer Treatment Reviews.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Santoro S., Santini M., Pepe C., Tognetti E., Cortelazzi C., Ficarelli E., De Panfilis G. Aromatase inhibitor-induced skin adverse reactions: exemestane-related cutaneous vasculitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(5):596–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bremec T., Demsar J., Luzar B., Pavlović M.D. Drug-induced pruritic micropapular eruption: anastrozole, a commonly used aromatase inhibitor. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15(7):14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fumal I., Danchin A., Cosserat F., Barbaud A., Schmutz J.L. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with tamoxifen therapy: two cases. Dermatology. 2005;210(3):251–252. doi: 10.1159/000083798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrew P., Valiani S., MacIsaac J., Mithoowani H., Verma S. Tamoxifen-associated skin reactions in breast cancer patients: from case report to literature review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;148(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trancart M., Cavailhes A., Balme B., Skowron F. Anastrozole-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(3):628–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCraken M., Benson E.A., Hickling P. Systemic lupus erythematosus induced by aminoglutethimide. Br Med J. 1980;281(6250):1254. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6250.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etherington J., Haynes P., Buchanan N. Effect of aminoglutethimide on the activity of a case of connenctive tissue disorder with features of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1993;2(6):387. doi: 10.1177/096120339300200611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lortholary A., Cary-Ten Have Dallinga M., El Kouri C., Morineau N., Ramée J.F. Paclitaxel-induced lupus. Presse Med. 2007;36(9 Pt 1):1207–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen M., Crowson A., Woofter M., Luca M., Magro C. Docetaxel (Taxotere) induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 4 cases. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(4):818–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marchetti M.A., Noland M.M., Dillon P.M., Greer K.E. Taxane associated subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19(8):19259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funke A.A., Kulp-Shorten C.L., Callen J.P. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus exacerbated or induced by chemotherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(10):1113–1116. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weger W., Kränke B., Gerger A., Salmhofer W., Aberer E. Occurrence of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus after treatment with fluorouracil and capecitabine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(2 Suppl. 1):S4–S6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callen J. Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus – filling the gap in knowledge. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(9):1075–1076. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.4958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sontheimer R.D., Maddison P.J., Reichlin M., Jordon R.E., Stastny P., Gilliam J.N. Serologic and HLA associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, a clinical subset of lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97(5):664–671. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-5-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe G., Henderson C., Hansen C., Sontheimer R. A systematic review of drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Brit J Dermatol. 2011;164(3):465–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong N.Y., Parsons L.M., Trotter M.J., Tsang R.Y. Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with docetaxel chemotherapy: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2014;5(7):785. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lebeau S., Tambe S., Sallam M., Alhowaish A., Tschanz C., Masouye I. Docetaxel-induced relapse of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;1109:871–874. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madrid F.F., Maroun M.C., Olivero O.A., Long M., Stark A. Autoantibodies in breast cancer sera are not epiphenomena and may participate in carcinogenesis. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(15):407. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1385-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans K.G., Heymann W.R. Paraneoplastic subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: an underrecognized entity. Cutis. 2013;91:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLean D. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:765–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sthoeger Z.M., Zinger H., Mozes E. Beneficial effects of the anti-estrogen tamoxifen on systemic lupus erythematosus of (NZB × NZW)F1 female mice are associated with specific reduction of IgG3 autoantibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:341–346. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cutolo M., Wilder R.L. Different roles of androgens and estrogens in the susceptibility to autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2000;26:825–839. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanda N., Tsuchia T., Tamaki K. Estrogen enhancement of anti-ds-DNA antibody and immunoglobulin G production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:328–337. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199902)42:2<328::AID-ANR16>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Styrt B., Sugarman B. Estrogens and infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:1139–1150. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.6.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pathmarajah P., Shah K., Taghipour K., Ramachandra S., Thorat M. Letrozole-induced necrotising leukocytoclastic small vessel vasculitis: first report of a case in the UK. Int J Surgery. 2015;16:77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Digklia A., Tzika E., Voutsadakis I.A. Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis associated with letrozole. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2014;20(2):146–148. doi: 10.1177/1078155213480535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong M., Grossman J., Hahn B.H., La Cava A. Cutaneous vasculitis in breast cancer treated with chemotherapy. Clin Immunol. 2008;129(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shoda H., Inokuma S., Yajima N., Tanaka Y., Setoguchi K. Cutaneous vasculitis developed in a patient with breast cancer undergoing aromatase inhibitor treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(4):651–652. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.023150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertolini E., Letho-Gyselinck H., Prati C., Wendling D. Rheumatoid arthritis and aromatase inhibitors. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78(1):62–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morel B., Marotte H., Miossec P. Will steroidal aromatase inhibitors induce rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(4):557–558. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chao J., Parker B.A., Zvaifler N.J. Accelerated cutaneous nodulosis associated with aromatase inhibitor therapy in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(5):1087–1088. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J.Y., Ballou S.P. The effect of antiestrogen agents on risk of autoimmune disorders in patients with breast cancer. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(1):55–59. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.140367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ray A., Ficek M. Immunomodulatory effects of anti-estrogenic drugs. Acta Pharm. 2012;62:141–155. doi: 10.2478/v10007-012-0012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bauml J., Chen L., Chen J., Boyer J., Kalos M., Li S.Q. Arthralgia among women taking aromatase inhibitors: is there a shared inflammatory mechanism with co-morbid fatigue and insomnia? Breast Cancer Res. 2015;28(17):89. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0599-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Servitja S., Martos T., Rodriguez Sanz M., Garcia-Giralt N., Prieto-Alhambra D., Garrigos L. Skeletal adverse effects with aromatase inhibitors in early breast cancer: evidence to date and clinical guidance. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2015;7(5):291–296. doi: 10.1177/1758834015598536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaillard S., Stearns V. Aromatase inhibitor-associated bone and musculoskeletal effects: new evidence defining etiology and strategies for management. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(2):205. doi: 10.1186/bcr2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laroche M., Borg S., Lassoued S., De Lafontan B., Roché H. Joint pain with aromatase inhibitors: abnormal frequency of Sjögren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(11):2259–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pokhai G., Buzzola R., Abrudescu A. Letrozole-induced very early systemic sclerosis in a patient with breast cancer: a case report. Arch Rheumatol. 2014;29(2):126–129. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Felson D.T., Cummings S.R. Aromatase inhibitors and the syndrome of arthralgias with estrogen deprivation. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2594–2598. doi: 10.1002/art.21364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heidari B., Shirvani J.S., Firouzjahi A., Heidari P., Hajian-Tilaki K.O. Association between nonspecific skeletal pain and Vitamin D deficiency. Int J Rheum Dis. 2010;13:340–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niravath P. Aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia: a review. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(6):1443–1449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hershman D.L., Unger J.M., Crew K.D., Awad D., Dakhil S.R., Gralow J. Randomized multicenter placebo-controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids for the control of aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal pain: SWOG S0927. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1910–1917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Islam M.S., Wright G., Tanner P., Lucas R. A case of anastrazole-related drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis. Clin J Gastroenetrol. 2014;7(5):414–417. doi: 10.1007/s12328-014-0512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inno A., Basso M., Vecchio F.M., Marsico V.A., Cerchiaro E., D’Argento E. Anastrozole-related acute hepatitis with autoimmune features: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;31(11):32. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pretel M., Marques L., Espana A. Drug-induced lupus erythematosous. Atlas Dermosifiliorg. 2014;105(1):18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]