Abstract

Rationale: Reducing asthma exacerbation frequency is an important criterion for approval of asthma therapies, but the clinical features of exacerbation-prone asthma (EPA) remain incompletely defined.

Objectives: To describe the clinical, physiologic, inflammatory, and comorbidity factors associated with EPA.

Methods: Baseline data from the NHLBI Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP)-3 were analyzed. An exacerbation was defined as a burst of systemic corticosteroids lasting 3 days or more. Patients were classified by their number of exacerbations in the past year: none, few (one to two), or exacerbation prone (≥3). Replication of a multivariable model was performed with data from the SARP-1 + 2 cohort.

Measurements and Main Results: Of 709 subjects in the SARP-3 cohort, 294 (41%) had no exacerbations and 173 (24%) were exacerbation prone in the prior year. Several factors normally associated with severity (asthma duration, age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status) did not associate with exacerbation frequency in SARP-3; bronchodilator responsiveness also discriminated exacerbation proneness from asthma severity. In the SARP-3 multivariable model, blood eosinophils, body mass index, and bronchodilator responsiveness were positively associated with exacerbation frequency (rate ratios [95% confidence interval], 1.6 [1.1–2.1] for every log unit of eosinophils, 1.3 [1.1–1.4] for every 10 body mass index units, and 1.2 [1.1–1.4] for every 10% increase in bronchodilatory responsiveness). Chronic sinusitis and gastroesophageal reflux were also associated with exacerbation frequency (1.7 [1.4–2.1] and 1.6 [1.3–2.0]), even after adjustment for multiple factors. These effects were replicated in the SARP-1 + 2 multivariable model.

Conclusions: EPA may be a distinct susceptibility phenotype with implications for the targeting of exacerbation prevention strategies.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 01760915).

Keywords: exacerbation-prone asthma, bronchodilator reversibility, eosinophils, sinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Although exacerbation-prone patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have been identified, this phenotype has not been systematically studied in asthma.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This is a multicenter cohort study of adults and children with severe asthma. Blood eosinophils, bronchodilator responsiveness, body mass index, chronic sinusitis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease were found to be associated with exacerbation-prone asthma, after adjustment for age, sex, race, center, and medication adherence, with replication of these findings in a second cohort. Exacerbation-prone asthma is a distinct phenotype with prominent extrapulmonary features that may be modifiable.

Asthma exacerbations are a significant public health problem and a risk for the progression to severe disease (1–3). Risk factors for exacerbation prevalence include sex, age, race, socioeconomic status, baseline lung function, smoking history, and exposure to respiratory viruses (3–10). Whether these factors contribute to frequent exacerbations is unclear. Many of these studies did not measure inflammatory markers (1, 4, 5, 7) or did so on a limited basis without significant findings (2, 6, 8). Although the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP)-1 + 2 network had very robust phenotyping of subjects at baseline (3), a dedicated analysis of factors related to exacerbation risk was challenged by a tabulation of exacerbation frequency with a simple dichotomous variable (presence or absence of three or more exacerbations) and an underrepresentation of children ages 6–11 years. By contrast, recent studies of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have shown that exacerbations become more frequent and more severe as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease progresses, and that the rate of occurrence reflects a susceptibility phenotype independent of smoking status and lung function (11). Similar data about an independent exacerbation susceptibility phenotype in asthma are lacking.

Numerous studies document the importance of type 2 inflammation in the development of asthma (e.g., Reference 12). Blood eosinophils and exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) levels associate with the prevalence of asthma exacerbations in large population studies (13, 14), and these biomarkers also can be useful in identifying patients responsive to biologic therapies that reduce exacerbations (15–18). Again, the risks of having frequent exacerbations are less well described from cohort studies of patients with severe asthma on existing therapy, while also collecting information about exposure history and comorbid conditions. Kupczyk and coworkers (9) showed that high levels of FeNO (>45 ppb) and smoking history increased the risk of having two or more exacerbations per year, but the study was limited by having only 14 adults with three or more exacerbations, and it did not include children with asthma.

We set out to explore the clinical, lung function, and inflammatory characteristics of adults and children with exacerbation-prone asthma (EPA) in the large asthma cohort recruited by the SARP-3, with enrollment criteria to include a proportion of children representing at least 25% of the cohort. SARP-3 is a National Institutes of Health/NHLBI network involving seven U.S. partnerships and a data coordinating center that is conducting studies to advance understanding of severe asthma through the integration of mechanistic studies with detailed phenotypic characterization procedures. Here we compare the baseline clinical and inflammatory features (including treatment responses to bronchodilators and systemic corticosteroids) in patients with three categories defined by the frequency of asthma exacerbation in the year before enrollment. We hypothesized that there are features of the exacerbation-prone phenotype that are independent of asthma severity and measures of type 2 inflammation. A portion of these data have been presented orally at the 2016 American Thoracic Society International Conference.

Methods

Study Population

Nonsmoking subjects 6 years and older with a physician diagnosis of asthma were recruited, particularly if they had been using high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and a second controller therapy for the last 3 months. All participants signed an informed consent, adherent to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each center and the NHLBI Data and Safety Monitoring Board. The diagnosis of asthma was confirmed by demonstration of relative change in postalbuterol FEV1 of greater than or equal to 12%, or a methacholine provocative concentration associated with a 20% decline in FEV1 less than or equal to 16 mg/ml. Thirteen subjects were enrolled at the discretion of the principal investigator with a prealbuterol FEV1 less than 50% predicted, lack of bronchodilator responsiveness, and no methacholine challenge data because of concerns for safety; a post hoc sensitivity analysis demonstrated that exclusion of these subjects would not change the reported results. Consistent with the 2012 definition of severe asthma (19), asthma control and risk were evaluated by the Asthma Control Test, questions regarding exacerbation frequency and health care use, the presence or absence of FEV1% predicted less than 80%, and questions regarding past instability during trials of stepping down the ICS dose. Exclusion criteria and procedures are listed in the online supplement. By design, 60% of the cohort had severe asthma and 25% were children.

Number of Exacerbations

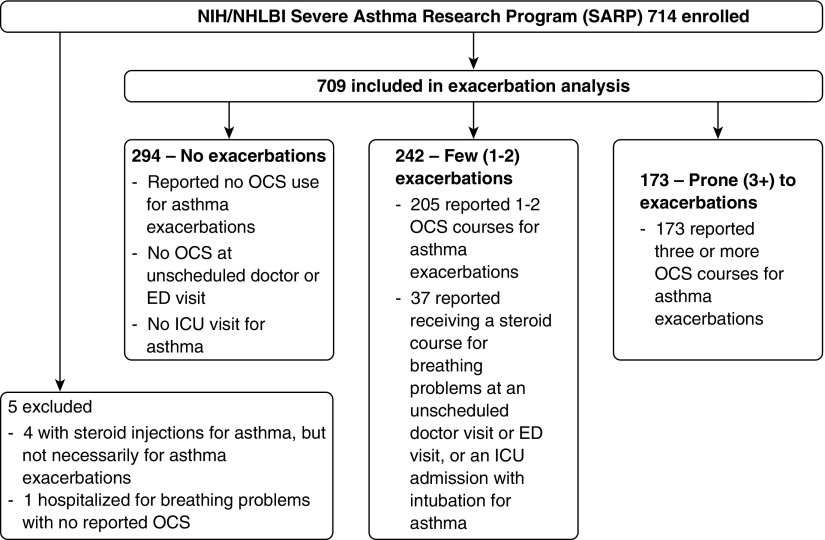

The frequency of asthma exacerbations was determined from self-reported number of systemic corticosteroid courses lasting 3 or more days for asthma in the past 12 months on a medication history intake questionnaire (see online supplement, which also includes questions related to comorbid conditions). The number of oral corticosteroid (OCS) courses was queried in the context of self-reported exacerbations. Questions regarding hospitalizations or emergency department visits for asthma were also reviewed. Figure 1 is a consort diagram for this analysis. The SARP network has previously used three or more exacerbations a year as a definition for subjects prone to these events (3).

Figure 1.

Classification of asthma exacerbation frequency in the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP)-3 baseline cohort. The frequency of asthma exacerbations was determined from self-reported number of oral corticosteroid (OCS) courses for asthma in the past 12 months on a medication history intake questionnaire, modified for 37 participants by questionnaire responses on a separate allergy and asthma history intake form. These 37 reported zero exacerbations but also reported intubations for asthma or OCS courses received at unscheduled doctor or emergency department visits for breathing problems, and were therefore reclassified as having had one exacerbation. A post hoc sensitivity analysis demonstrated that exclusion of these subjects did not affect the results. Because scheduled monthly steroid injections for asthma could not be separated from steroid injections received for exacerbations, four participants were excluded from analysis. An additional participant was excluded with a reported hospitalization for breathing problems with no reported OCS use. ED = emergency department; ICU = intensive care unit; NIH = National Institutes of Health.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical measures were summarized by percentages within exacerbation frequency categories (0, 1–2, ≥3 exacerbations), with a Pearson chi-square test for associations. Fisher exact chi-square tests were used where small cell counts were observed. Similarly, continuous measures were summarized by either median and first and third quartiles or mean and SD, with Kruskal-Wallis and linear regression tests for differences, respectively, among exacerbation frequency categories.

The frequency of exacerbations outcome was also examined as a discrete count using univariable negative binomial regression models. Twelve outlier values with 12–15 reported OCS courses were truncated to 10+ exacerbations. Maximum bronchodilator reversibility is presented as an absolute change in the percent predicted values, a method that avoids bias by sex and baseline lung volume (20). Blood eosinophil counts and sputum eosinophils were examined on the log scale with zero values replaced with a quantity approximately half of the smallest nonzero value, and an indicator variable for these replacement values added to any statistical models. Description of the modeling process can be found in the online supplement. Results are not corrected for multiple comparisons and are considered exploratory.

Results

Clinical Associations with Exacerbation Frequency

We found that among 709 SARP-3 participants (including 187 children), 294 (41%) had no exacerbations, 242 (34%) had few exacerbations, and 173 (24%) were exacerbation prone (Figure 1). As expected, categories of exacerbation frequency were directly associated with asthma severity (P < 0.001) (Table 1). However, 110 participants (37%) of the control group without exacerbations had severe disease; these subjects also represent 26% of the patients in the entire study with severe disease. Additionally, 21 (12%) participants with EPA did not meet criteria for severe disease (Table 1). Asthma duration did not differ across exacerbation categories (Table 1), nor did the estimated age of asthma onset (P = 0.899). Only adults had differences in mean ages across the exacerbation categories; specifically, those with EPA were older than patients in the other two groups (P = 0.003) (Table 1). In comparing the EPA group with those without exacerbations, there were no differences in the distributions of sex, race, or ethnicity (Table 1). The group with few (one to two) exacerbations in the last year had a lower proportion of white persons, and a higher proportion of African Americans (Table 1). Participants with EPA were had a higher body mass index (BMI) than patients with few or no exacerbations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Exacerbation Frequency

| Number of Systemic Corticosteroid Bursts |

P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Few (1–2) | Prone (≥3) | ||

| N | 294 | 242 | 173 | |

| Severe asthma, n (%),* CS | 110 (37) | 157 (65) | 152 (88) | <0.001 |

| Asthma duration, yr, median (IQR) | 24 (12–38) | 19 (10–37) | 19 (9–39) | 0.208 |

| Adults (≥18) | ||||

| N (column %, row %) | 236 (80, 45) | 163 (67, 31) | 123 (71, 24) | — |

| Age, yr, median (IQR),* KW | 47 (33–55) | 50 (38–58) | 52 (41–60) | 0.003 |

| Adolescents (12–18) | ||||

| N (column %, row %) | 29 (10, 41) | 21 (9, 30) | 21 (12, 30) | — |

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 15 (13–16) | 14 (14–15) | 14 (13–15) | 0.155 |

| Children (6–11) | ||||

| N (column %, row %),* CS Bonferroni | 29 (10, 25) | 58 (24, 50) | 29 (17, 25) | — |

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 10 (9–11) | 10 (9–11) | 9 (8–10) | 0.108 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 166 (57) | 152 (63) | 104 (60) | 0.323 |

| White race, n (%),* CS | 175 (60) | 122 (50) | 107 (62) | 0.036 |

| African race, n (%),* CS | 79 (27) | 92 (38) | 41 (24) | 0.003 |

| Mixed or other race, n (%) | 40 (14) | 28 (12) | 25 (15) | 0.649 |

| Hispanic ethnicity, n (%) | 21 (7) | 16 (7) | 9 (5) | 0.716 |

| Education, highest obtained in household,*† median, CS | Bachelor’s degree | Associate’s degree | Associate’s degree | 0.018 |

| Income, $,‡ categorical range, median | 50,000–99,999 | 25,000–49,999 | 50,000–99,999 | 0.333 |

| BMI, adults,* KW | 29 (26–35) | 32 (27–39) | 33 (28–39) | <0.001 |

| BMI, percentile (children),* KW | 81 (56–96) | 86 (57–97) | 95 (86–98) | 0.004 |

| Number of controller medications,* KW | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–4) | <0.001 |

| High-dose ICS, n (%),* CS | 132 (45) | 162 (67) | 144 (83) | <0.001 |

| LABA, n (%),* CS | 186 (63) | 192 (79) | 157 (91) | <0.001 |

| LTRA, n (%),* CS | 84 (29) | 117 (48) | 97 (56) | <0.001 |

| Biologics, n (%),* CS | 8 (3) | 17 (7) | 20 (12) | <0.001 |

| Daily OCS, n (%) (past 3 mo),* CS | 4 (1) | 23 (10) | 51 (30) | <0.001 |

| Medication Adherence Report Scale score (of 25 points) | 23 (20, 24) | 23 (21, 24) | 23 (21, 24) | 0.480 |

| Asthma Control Test score,* LR | 20 (17–22) | 17 (14–20) | 15 (10–18) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CS = chi-square test; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; IQR = interquartile range; KW = Kruskal-Wallis test; LABA = long-acting β2-agonist; LR = linear regression test; LTRA = leukotriene receptor antagonist; OCS = oral corticosteroid.

The categories of exacerbation frequency are based on recall from the 12 months before the baseline visit. Percent values associated with tabulated data refer to column comparisons, except when denoted as row statistics.

Significance with P less than 0.05, using the CS, KW, or LR as appropriate.

Education categories, ranked from lowest to highest: 0 = no high school diploma; 1 = GED; 2 = high school diploma; 3 = technical training; 4 = some college, no degree; 5 = Associate's degree; 6 = Bachelor's degree; 7 = Master's degree; 8 = M.D./Ph.D./J.D./Pharm.D.

Income categories: 1 = less than $25,000; 2 = $25,000 to $49,999; 3 = $50,000 to $99,999; 4 = $100,000 or more.

Those with EPA were using more controller therapies (P < 0.001 in all cases), without a difference in medication compliance survey scores (P = 0.480) (Table 1). Despite these treatments, participants with EPA had the lowest Asthma Control Test scores (Table 1). Asthma-related health care use also increased with categories of exacerbation frequency, particularly with respect to visits to the emergency department and hospitalizations (5% and 0% of the group with no exacerbations respectively, 46% and 18% of those with few exacerbations, and 58% and 35% of those with EPA). Notably, only six (3.4%) participants with EPA met the definition for severe asthma solely on the basis of exacerbation frequency.

Lung Function and Inflammation

Compared with the other groups, participants with EPA had lower lung function at baseline (Table 2). Regardless of exacerbation history, children had normal mean FEV1 and FVC measurements; however, only children without exacerbations had a mean FEV1/FVC in the normal range (z ≥ −1.64) (Table 2). Mean FEV1 values were progressively lower across exacerbation categories, and patients with EPA had the lowest lung function (Table 2); this relationship was also observed for forced expiratory flow, midexpiratory phase (FEF25–75%) in adults and children (P = 0.001 and 0.005, respectively). There were a few subsets of participants with discordance between exacerbation frequency and categories of lung function. Nearly 14% of the adults and 24% of children with an FEV1% predicted greater than or equal to 80 were exacerbation prone, and 29% of adults with an FEV1% predicted less than 60 had no exacerbations (Table 2). The presence of airway closure (FVC % predicted <80) was enriched across exacerbation categories (26%, none; 31%, few; and 42%, prone; P = 0.002). In unadjusted models stratified by age, the fitted number of exacerbations increased as lung function declined (Figure 2A for FEV1 z score; similar relationships were observed for FEV1/FVC and FVC z scores, not shown).

Table 2.

Lung Function by Categories of Exacerbation Frequency

| Number of Systemic Corticosteroid Bursts |

P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (Children: n = 58; Adults: n = 236) | Few (1–2) (Children: n = 79; Adults: n = 163) | Prone (≥3) (Children: n = 50; Adults: n = 123) | ||

| FEV1 /FVC | ||||

| Children,* LR | ||||

| Ratio | 0.78 ± 0.09 | 0.76 ± 0.09 | 0.75 ± 0.1 | 0.091 |

| z score | −1.34 ± 0.97 | −1.67 ± 1.17 | −1.81 ± 1.20 | 0.072 |

| Adults,* LR | ||||

| Ratio | 0.70 ± 0.09 | 0.69 ± 0.11 | 0.65 ± 0.13 | <0.001 |

| z score | −1.62 ± 1.10 | −1.60 ± 1.29 | −1.93 ± 1.51 | 0.050 |

| FEV1 | ||||

| Children,* LR | ||||

| % Predicted | 94.09 ± 13.24 | 88.87 ± 16.70 | 86.16 ± 19.08 | 0.036 |

| z score | −0.48 ± 1.06 | −0.87 ± 1.30 | −1.07 ± 1.45 | 0.046 |

| Adults,* LR | ||||

| % Predicted | 76.79 ± 18.73 | 72.26 ± 20.12 | 63.96 ± 21.52 | <0.001 |

| z score | −1.62 ± 1.28 | −1.89 ± 1.34 | −2.50 ± 1.44 | <0.001 |

| FVC | ||||

| Children | ||||

| % Predicted | 105.24 ± 11.61 | 102.72 ± 15.86 | 100.50 ± 16.23 | 0.245 |

| z score | 0.43 ± 0.95 | 0.22 ± 1.28 | 0.04 ± 1.34 | 0.245 |

| Adults,* LR | ||||

| % Predicted | 88.97 ± 17.18 | 83.92 ± 17.40 | 77.45 ± 17.57 | <0.001 |

| z score | −0.79 ± 1.26 | −1.14 ± 1.27 | −1.65 ± 1.31 | <0.001 |

| Postalbuterol change in FEV1% predicted | ||||

| Children,* LR | 11.40 ± 8.46 | 16.13 ± 10.31 | 15.93 ± 10.51 | 0.012 |

| Adults | 10.73 ± 7.66 | 11.27 ± 8.01 | 12.73 ± 8.07 | 0.073 |

| FEV1 ≥80% predicted, n (row %, column %) | ||||

| Children (n = 139) | 48 (34.5, 83) | 58 (41.7, 73) | 33 (23.7, 66) | 0.135 |

| Adults (n = 189),* CS | 104 (55.0, 44) | 59 (31.2, 36) | 26 (13.7, 21) | <0.001 |

| FEV1 <60% predicted, n (row %, column %) | ||||

| Children (n = 6) | 0 (0, 0) | 3 (50, 4) | 3 (50, 6) | 0.195 |

| Adults (n = 137),* CS | 40 (29, 17) | 42 (31, 26) | 55 (40, 45) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: CS = chi-square test; LR = linear regression test.

All data reflect prealbuterol values unless specified, and the lung function reference values are derived from the Quanjer dataset (35). The lower limit of normal reflects a z score less than −1.64, with 95% of the healthy, age-stratified reference population having z scores greater than or equal to this value. Percent values associated with tabulated data refer to column comparisons. Continuous variables are expressed as means ± SD or medians with the first and third quartiles in parentheses.

Significance with P less than 0.05, using the linear regression or Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate.

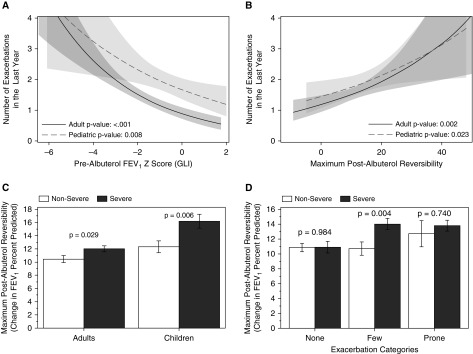

Figure 2.

Unadjusted models of exacerbation frequency by measures of lung function. Negative binomial models were used to generate regression curves with the fitted numbers of exacerbations on the y-axis. The line is the fitted value and the shading is the 95% confidence interval with regression lines overlaid from children (dashed line, lighter gray) and adults (solid line, darker gray). Significance testing refers to the slope of the model in the log scale for exacerbations with prealbuterol FEV1 z scores and maximum postalbuterol reversibility in A and B, respectively. Severity stratified mean and SE values of bronchodilator responsiveness are also shown with further stratification by age (C) or exacerbation categories (D) (None = 0, Few = 1 to 2, and Prone = 3 or more exacerbations). GLI = Global Lung Initiative.

Bronchodilator responsiveness tracked with exacerbation frequency. Mean values for maximum albuterol responsiveness increased across exacerbation categories for children, with a trend for adults (Table 2). For both age groups, unadjusted models of exacerbation frequency showed a linear relationship between the risk of exacerbation and the improvement in FEV1% predicted after albuterol (Figure 2B). Adults and children with severe asthma have more albuterol reversibility than participants with nonsevere disease (Figure 2C). However, when the analysis is stratified by categories of exacerbation, severity only impacts bronchodilator responsiveness for subjects with few exacerbations (Figure 2D). Finally, in the subset of the cohort without relative postalbuterol FEV1 reversibility greater than or equal to 12% at the screening visit, airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine did not differ between exacerbation frequency groups (P = 0.531; n = 314).

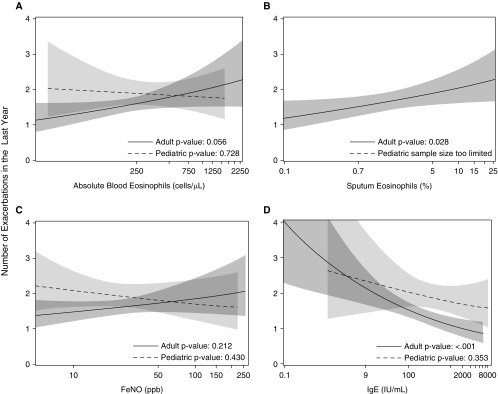

The relationships between exacerbation frequency and four measures of type 2 inflammation are inconsistent. Median levels of blood eosinophils did not differ across exacerbation category but there was a trend between these levels in adults and unadjusted regression models of exacerbation frequency (Table 3, Figure 3A). Among adults but not children, median sputum eosinophils were lower in the group without exacerbations compared with the other two categories (Table 3). This relationship for sputum eosinophils held up in the unadjusted regression model (Figure 3B). By contrast, sputum neutrophils were not associated with EPA in the categorical analyses or univariable regression model (P > 0.1 in both cases). Levels of FeNO did not differ by categories of exacerbation frequency or in regression models (Table 3, Figure 3C). In contrast to expectations, adults with frequent exacerbations had the lowest levels of blood IgE compared with the other groups and the smallest number of positive allergen-specific IgE results (Table 3). The unadjusted regression model of exacerbation frequency in adults (but not children) showed an inverse relationship between IgE levels and the risk of exacerbation (Figure 3D). These relationships remained significant with or without exclusion of participants on omalizumab, who only represent 6% of the cohort.

Table 3.

Type 2 Inflammatory Markers by Categories of Exacerbation Frequency

| Number of Systemic Corticosteroid Bursts |

P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Few (1–2) | Prone (≥3) | ||

| Blood EOS, absolute cell count/μl | ||||

| Children (n = 187) | 363 (182, 581) | 319 (175, 522) | 415 (196, 514) | 0.911 |

| Adults (n = 521) | 201 (121, 315) | 207 (130, 372) | 230 (116, 442) | 0.461 |

| Sputum EOS, % | ||||

| Children (n = 43) | 1.5 (0.1, 10.2) | 0.9 (0.4, 3) | 1.2 (0.3, 2.5) | 0.889 |

| Adults (n = 403),* KW | 0.5 (0, 2) | 0.9 (0, 3.5) | 0.9 (0.2, 5.2) | 0.028 |

| FeNO, ppb | ||||

| Children (n = 183) | 33 (12, 63) | 22 (12, 41) | 20 (12, 44) | 0.141 |

| Adults (n = 518) | 22 (14, 35) | 23 (13, 39) | 25 (13, 42) | 0.606 |

| Blood IgE, IU/mL (excludes subjects on biologics) | ||||

| Children (n = 170) | 418 (201, 834) | 467 (142, 1,164) | 334 (169, 952) | 0.982 |

| Adults (n = 480),* KW | 161 (56, 363) | 163 (40, 386) | 93 (27, 291) | 0.007 |

| Number of positive specific IgEs (of 15 tests) | ||||

| Children | 7 (3, 11) | 7 (3, 12) | 6 (3, 9) | 0.566 |

| Adults,* CS | 4 (2, 8) | 3 (1, 7) | 2 (0, 5) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: CS = chi-square test; EOS = eosinophils; FeNO = exhaled nitric oxide; KW = Kruskal-Wallis test.

Data are expressed as median (interquartile range).

Significance with P less than 0.05, using the chi-square or Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate.

Figure 3.

Unadjusted models of exacerbation frequency by measures of type 2 inflammation. Negative binomial models were used to generate regression curves with the fitted numbers of exacerbations on the y-axis. The line is the fitted value and the shading is the 95% confidence interval with regression lines overlaid from children (dashed line, lighter gray) and adults (solid line, darker gray). Significance testing refers to the slope of the model in the log scale for exacerbations. Blood eosinophils, sputum eosinophil percents, exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), and total IgE values are shown in A–D, respectively. Each panel has regression lines overlaid from children (dashed line) and adults (solid line).

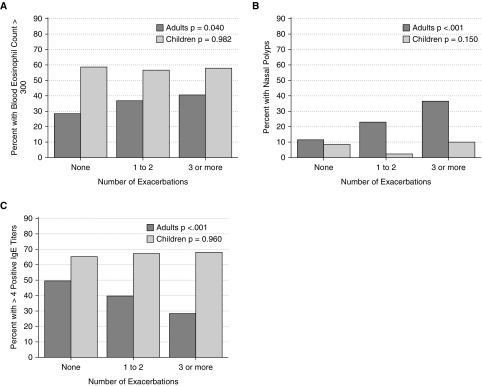

The distributions of categorical assessments of blood eosinophil levels and degree of allergic sensitization were different between adults and children. Figure 4 shows that children have a higher proportion of subjects than adults with blood eosinophils greater than 300 cells/μl or with polysensitization to aeroallergens (four or more allergen-specific IgE values above normal) (Figures 4A and 4C). Adults but not children with EPA have a higher proportion of subjects with high blood eosinophils or with nasal polyps than other exacerbation categories (Figures 4A and 4B). Conversely, adults with EPA have a lower proportion of subjects compared with other exacerbation categories with evidence of polysensitization (Figure 4C). These relationships are not significant for children and together suggest that the exacerbation-prone phenotype is not driven by allergic sensitization.

Figure 4.

Exacerbation-prone asthma in adults associates with eosinophilic inflammation despite lower measures of atopy. The percent of subjects with the designated categorical measure of type 2 inflammation is stratified by age and exacerbation category. Significance testing reflects the age-stratified trend across all three categories of exacerbation frequency.

Comorbid Conditions Associate with Exacerbation Frequency in Multivariable Models

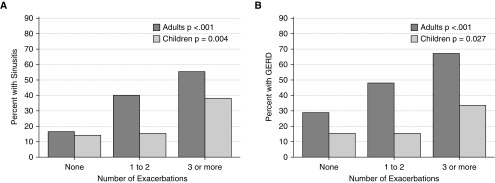

Reporting of multiple comorbid conditions was more frequent in the EPA group compared with those with few or no exacerbations. In adults, for example, those with EPA compared with other groups had higher proportions with hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, diabetes mellitus, and osteoporosis, but not coronary artery disease (Table 4). Conversely, EPA had the lowest proportion of subjects without comorbid conditions. We hypothesized chronic sinusitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) would be associated exacerbation frequency across age groups, and could be envisioned to contribute to lower airway inflammation. Figure 5 shows that the prevalence of both of these comorbid conditions increases with categories of exacerbation frequency in both adults and children. In a multivariable model, sinusitis and GERD remained significantly associated with exacerbation frequency, even after adjustment for age, sex, race, center, medication adherence, BMI, bronchodilator reversibility, blood eosinophil counts, and IgE levels (Table 5). When FEV1% predicted is used as the lung function variable instead of bronchodilator reversibility, the rate ratio for this factor is 0.9 (95% confidence interval, 0.8–0.9; P < 0.001) for every 10% change in lung function with minimal impact on the rest of the model.

Table 4.

Adult Comorbid Diseases by Categories of Exacerbation Frequency

| Number of Systemic Corticosteroid Bursts |

P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (n = 236) | Few (1–2) (n = 163) | Prone (≥3) (n = 123) | ||

| Hypertension | 65 (28) | 58 (36) | 54 (44) | 0.007 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 33 (14) | 38 (23) | 36 (29) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (4) | 20 (12) | 15 (12) | 0.005 |

| Osteoporosis | 7 (3) | 13 (8) | 15 (12) | 0.003 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2 (1) | 5 (3) | 4 (3) | 0.190 |

| No comorbid conditions | 152 (64) | 82 (50) | 51 (41) | <0.001 |

The number of adults with the indicated comorbid disease is reported along with a column percentage in parentheses. Significance across exacerbation categories with P less than 0.05 is noted using the chi-square test.

Figure 5.

Selected comorbidities associated with exacerbation frequency. The percent of subjects with chronic sinusitis (A) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (B) are stratified by categories of exacerbation frequency and by age. Significance testing reflects the age-stratified trend across all three categories of exacerbation frequency.

Table 5.

Multivariable Negative Binomial Model of Exacerbation Rates

| Factor | Annual Rate of Exacerbations |

Unit | Rate Ratio | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Present | Factor Absent | ||||

| Categorical | |||||

| White | 3.6 (2.6–5.2) | 3.1 (2.2–4.4) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 0.119 | |

| Female sex | 3.4 (2.4–4.8) | 3.3 (2.3–4.7) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.721 | |

| Sinusitis | 4.4 (3.1–6.2) | 2.5 (1.8–3.6) | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | <0.001 | |

| GERD | 4.2 (3.0–6.0) | 2.6 (1.9–3.8) | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) | <0.001 | |

| Continuous | |

||||

| Age, yr | |

10 | 1 (0.9–1.1) | 0.580 | |

| Maximum postalbuterol reversibility, % FEV1 predicted | |

10 | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | <0.001 | |

| BMI (adults), kg/m2 | |

10 | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | <0.001 | |

| BMI percentile (children <18) | |

10 | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) | ||

| IgE, IU/mL (log) | |

1 | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.009 | |

| Blood eosinophils, cells/μL (log) | 1 | 1.6 (1.1–2.1) | 0.004 | ||

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Point estimates are shown with the 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. In addition to the factors listed in the table, this model is also adjusted for clinical center and Medication Adherence Report score (not significant).

The relationships between sinusitis, GERD, and exacerbation frequency remained significant even after the addition of severe asthma status to the multivariable model (P < 0.001). To reduce the likelihood of misclassification, sinusitis remained significant when we restricted the analysis to subjects reporting a history of surgery for sinusitis or nasal polyps (P < 0.001). Moreover, patients with EPA were the least likely to report the absence of reflux symptoms (60% of patients with EPA, compared with 76% of patients with few exacerbations and 79% with no exacerbations; P < 0.001), despite having the greatest proportion of subjects on acid suppression therapy (49% EPA, 29% few, 20% none, respectively; P < 0.001). Finally, the association between with GERD and exacerbation frequency was preserved when FVC % predicted was used in the multivariable model instead of bronchodilator reversibility (P < 0.001), as a way to adjust for hyperinflation potentially contributing to the likelihood of GERD.

We performed a replication analysis of this multivariable model using the SARP-1 + 2 cohort. Because exacerbation frequency was available in this cohort only as a dichotomous indicator of three or more exacerbations, we ran modified Poisson regression models of both data sets for direct comparison (Table 6). Blood eosinophils, BMI, sinusitis, and GERD are highly associated with exacerbation frequency in all models. Replication of the effect due to bronchodilator reversibility was significant in the SARP-3 Poisson model and approached significance in the SARP-1 + 2 model (P = 0.065). The effect sizes for these five risk factors were similar in both cohorts. Race was not associated with exacerbation frequency in either cohort. Only the SARP-1 + 2 model showed a significant effect for both female sex and age, and did not replicate the inverse association between exacerbation frequency and IgE observed in SARP-3.

Table 6.

Replication Analysis with the SARP-1 + 2 Cohort

| SARP-3 (n = 709) |

SARP-1 + 2 (n = 1,199) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| White | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 0.231 | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.093 |

| Female sex | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.712 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.005 |

| Sinusitis | 1.7 (1.2–2.2) | <0.001 | 1.3 (1.1–1.7) | 0.019 |

| GERD | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | <0.001 | 2.3 (1.9–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.477 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.033 |

| Maximum postalbuterol reversibility | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.046 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.067 |

| BMI | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.005 | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | 0.006 |

| IgE (log) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.045 | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.123 |

| Blood eosinophils (log) | 1.8 (1.2–2.7) | 0.009 | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 0.009 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; SARP = Severe Asthma Research Program.

Exacerbation frequency in the SARP-1 + 2 cohort was defined as a binary outcome denoting the presence or absence of three or more exacerbations in the last year. An equivalent binary outcome was created for the SARP-3 data to allow fitting of comparable models for the two cohorts. For continuous predictor variables, the same units were applied as in Table 5. Adjustment for center was present in both models. None of the participants of SARP-1 + 2 were using omalizumab, so this adjustment is present only in the SARP-3 model.

Discussion

This study describes the clinical, lung function, inflammatory, and comorbid characteristics of EPA in a well-phenotyped, multicenter cohort of patients of diverse age, enriched for severe disease. Exacerbations drive prescription practice, so it is not surprising that the EPA group has the highest medication burden and similar compliance scores (Table 1). Although exacerbations have long been associated with asthma severity, we believe EPA is a distinct phenotype for the following reasons. First, it is notable that of the patients with no exacerbations in the prior year, 37% have severe disease (Table 1), and 26% of the adults have severe obstruction with an FEV1 less than 60% predicted (Table 2). Conversely, of patients with EPA 12% have nonsevere asthma at baseline (Table 1) and nearly 16% of the adults have a FEV1 greater than or equal to 80% predicted (Table 2). This discordance is similar to that noted by others (9) and suggests that there are pathophysiologic mechanisms contributing to exacerbations that are distinct from those driving asthma severity. Second, the lack of association between EPA and asthma duration, age of onset, race, and socioeconomic background is strikingly different than prior observations about severe asthma (2, 3). Inclusion of young children ages 6–11 years in the SARP-3 cohort may have balanced the risks of EPA due to sex and age observed in the SARP-1 + 2 population.

Third, the addition of either one of two definitions of severe asthma (based on medication burden alone [high-dose ICS and a second controller], or medications and the presence high-risk domain item, such as Asthma Control Test scores ≤19) did not undermine the multivariable model of EPA. Finally, bronchodilator responsiveness is not different between severe and nonsevere participants in two important subgroups of participants, those with no exacerbations and those with EPA. In support of this, patients with EPA have been shown to have enhanced capacity for airway closure compared with FEV1-matched control subjects without EPA (21). These findings raise the question as to whether EPA is associated with unique features of airway remodeling, such as smooth muscle hypertrophy and/or basement membrane thickening.

A few aspects of the multivariable model are similar to prior observations. Higher BMI and lower baseline lung function are factors that are expected to relate to exacerbation frequency (21–23). Lung function and BMI were vastly different among SARP clusters (23), and in this regard it is interesting to note that the baseline SARP cluster status was not associated with the risk of exacerbation in the following year (24). The association of sinusitis and GERD with exacerbation frequency found in the multivariable model replicates the findings of ten Brinke and coworkers (5) and the strength of this finding in our study may simply be a reflection of a larger data set. Although the screening questions for these disorders were simple (yes/no), the analysis of responses to follow-up questions was consistent and suggested protection against misclassification error. Because hyperinflation can predispose subjects to having GERD (25, 26), we also substituted prealbuterol FVC % predicted in the multivariable model. This substitution did not diminish the association between GERD and EPA. Because microaspiration of upper airway and oral secretions can happen during sleep in these conditions (27), it is possible that chronic sinusitis and GERD are part of the causal pathway leading toward asthma exacerbation risk.

Measures of type 2 inflammation likely relate to both risk of exacerbation and treatment response, making evaluation of EPA complex particularly in the setting of ongoing therapy, which may have differential responses on these biomarkers. For example, the strength of the associations between exacerbation frequency and blood eosinophils increased after adjustment for other factors, and was replicated in the SARP-1 + 2 cohort despite a higher prevalence of maintenance OCS therapy. We did not observe an association to FeNO levels, a marker easily suppressed by compliance with ICS therapy. This is in contrast to a smaller study by Kupczyk and coworkers (9) showing a link between EPA status and elevated FeNO levels, but consistent with a larger retrospective biomarker analysis of two recent clinical trials (28). Additionally, adults in the SARP-3 cohort seem to have an inverse relationship between exacerbations and IgE levels (Figure 3) or degree of allergen polysensitization (Table 3, Figures 3 and 4). Although it is possible that patients with atopic asthma may respond better to ICS than patients with nonatopic disease, and therefore have a greater likelihood of maintaining control and exacerbation-free status, the lack of replication in the SARP-1 + 2 cohort raises questions about the strength of the findings related to IgE levels. Prior studies have shown a lack of association between IgE levels and measures of asthma control, and lower levels of IgE in patients with poor bronchodilator responsiveness (15, 28). Collectively, although patients with high levels of type 2 inflammatory biomarkers are at increased risk of exacerbation, those with frequent exacerbation may or may not have high levels of type 2 inflammation at the time of assessment.

Our study has potential limitations. First, the precision of 12-month recall for the frequency of exacerbations is not ideal. To address this, we used a series of questions (see Table E1 in the online supplement) that asked about exacerbations in different ways and developed a method of cross-checking to minimize misclassification of patients in the group with no events. A similar strategy was used for questions pertaining to the comorbid conditions that also included questions about comorbid condition-related medication use or surgeries. Second, we are unable to precisely determine the triggers for these exacerbations or to reliably assess the impact of maintenance controller therapy in use at the time of the exacerbation. Third, it is likely that the prior exacerbation history influenced medication use and other factors influencing the lung function and biomarker data collected at baseline. With this in mind, these findings are associations, which may or may not be useful for predictive purposes. Fourth, certain risk factors reported in prior studies (e.g., reduced interferon production) could not be determined in this retrospective epidemiologic study. Finally, it is likely that the risks for EPA differ across the endotypes of this disease, and that the structure of the present analysis may miss some of these factors.

Nonetheless, the replication of our findings in a second cohort strengthens the external validity. Specifically, blood eosinophils, bronchodilator responsiveness, BMI, sinusitis, and GERD associate with exacerbation frequency in the multivariable models and each of these factors is potentially modifiable. For example, in addition to targeting blood eosinophils, a recent metaanalysis suggests addition of tiotropium to regimens containing both ICS and long-acting β2-agonist may reduce exacerbations by 25% (29). Another strength of our study design is that these observations support hypotheses that will be tested longitudinally as the SARP-3 cohort completes its annual follow-up in the longitudinal portion of this study, an approach that recently helped build predictive models of exacerbation in patients with milder disease at baseline (30). For example, if active sinusitis or symptomatic GERD at baseline predicts the prospective risk of exacerbation, would more aggressive management of these comorbid conditions help asthma control and future risk? The literature regarding surgical or medical therapy for these conditions has not supported broad use of these strategies to improve asthma control (31–34). However, these treatments may be worthy of trials selectively in patients with the exacerbation-prone phenotype. As the asthma care community finally has multiple modalities of therapeutic options, additional clinical trials are warranted to compare the efficacy of these agents with each other and begin to guide matching of patient phenotypes to individualized treatment decisions.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the study participants, the SARP-3 clinical research coordinators, and the data coordinating center. This study was conducted with the support of grants that were awarded by the NHLBI. Spirometers were provided for SARP by nSpire Health, Inc., Longmont, Colorado.

Footnotes

Supported by NHLBI to the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) Principal Investigators, Clinical Centers, and Data Coordinating Center as follows: U10 HL109164 (E.R.B.), U10 HL109257 (M.C.), U10 HL109250 (S.C.E.), U10 HL109146 (J.V.F.), U10 HL109250 (B.G.), U10 HL109172 (E.I. and B.D.L.), U10 HL109168 (N.N.J.), U10 HL109250 (W.G.T.), U10 HL109152 (S.E.W.), and U10 HL109086–04 (D.T.M.). As an ancillary study to SARP, RO1 HL115118 (L.C.D.) focused on the mechanisms of recovery from virus-induced asthma exacerbations. In addition, this program is supported through the following National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences awards: UL1 TR001420 (Wake Forest University), UL1 TR000427 (University of Wisconsin), UL1 TR001102 (Harvard University), and UL1 TR000454 (Emory University).

Author Contributions: Design, L.C.D., B.R.P., S.R., K.R., N.R.B., J.C.C., M.C., S.P.P., W.P., D.T.M., J.V.F., and N.N.J. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, L.C.D., B.R.P., S.R., K.R., N.R.B., J.C.C., M.C., S.P.P., W.P., S.A., L.B.B., E.R.B., S.A.A.C., A.C., M.DeB., S.C.E., S.B.F., M.F., A.M.F., J.G., B.G., A.T.H., G.A.H., F.H., A.-M.I., E.I., B.D.L., N.L., D.A.M., W.C.M., R.M., M.T.D.O., M.C.P., M.L.S., R.L.S., W.G.T., S.E.W., P.G.W., D.T.M., J.V.F., and N.N.J. Manuscript drafting and critique, L.C.D., B.R.P., N.R.B., J.C.C., M.C., S.P.P., W.P., R.L.S., W.G.T., S.E.W., D.T.M., J.V.F., and N.N.J.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

This is a corrected version of this article; it was posted online on March 30, 2018.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0419OC on August 24, 2016

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program-3 Investigators

References

- 1.Tattersfield AE, Postma DS, Barnes PJ, Svensson K, Bauer CA, O’Byrne PM, Löfdahl CG, Pauwels RA, Ullman A The FACET International Study Group. Exacerbations of asthma: a descriptive study of 425 severe exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:594–599. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.9811100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolan CM, Fraher KE, Bleecker ER, Borish L, Chipps B, Hayden ML, Weiss S, Zheng B, Johnson C, Wenzel S TENOR Study Group. Design and baseline characteristics of the epidemiology and natural history of asthma: Outcomes and Treatment Regimens (TENOR) study: a large cohort of patients with severe or difficult-to-treat asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;92:32–39. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61707-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore WC, Bleecker ER, Curran-Everett D, Erzurum SC, Ameredes BT, Bacharier L, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Chung KF, Clark MP, et al. National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program. Characterization of the severe asthma phenotype by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griswold SK, Nordstrom CR, Clark S, Gaeta TJ, Price ML, Camargo CA., Jr Asthma exacerbations in North American adults: who are the “frequent fliers” in the emergency department? Chest. 2005;127:1579–1586. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ten Brinke A, Sterk PJ, Masclee AA, Spinhoven P, Schmidt JT, Zwinderman AH, Rabe KF, Bel EH. Risk factors of frequent exacerbations in difficult-to-treat asthma. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:812–818. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00037905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koga T, Oshita Y, Kamimura T, Koga H, Aizawa H. Characterisation of patients with frequent exacerbation of asthma. Respir Med. 2006;100:273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishnan V, Diette GB, Rand CS, Bilderback AL, Merriman B, Hansel NN, Krishnan JA. Mortality in patients hospitalized for asthma exacerbations in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:633–638. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200601-007OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller MK, Lee JH, Miller DP, Wenzel SE TENOR Study Group. Recent asthma exacerbations: a key predictor of future exacerbations. Respir Med. 2007;101:481–489. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kupczyk M, ten Brinke A, Sterk PJ, Bel EH, Papi A, Chanez P, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, Gjomarkaj M, Gaga M, Brusselle G, et al. BIOAIR investigators. Frequent exacerbators: a distinct phenotype of severe asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:212–221. doi: 10.1111/cea.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson DJ, Johnston SL. The role of viruses in acute exacerbations of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1178–1187, quiz 1188–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Müllerova H, Tal-Singer R, Miller B, Lomas DA, Agusti A, Macnee W, et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) Investigators. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1128–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, Donaldson DD. Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science. 1998;282:2258–2261. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price DB, Rigazio A, Campbell JD, Bleecker ER, Corrigan CJ, Thomas M, Wenzel SE, Wilson AM, Small MB, Gopalan G, et al. Blood eosinophil count and prospective annual asthma disease burden: a UK cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:849–858. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malinovschi A, Fonseca JA, Jacinto T, Alving K, Janson C. Exhaled nitric oxide levels and blood eosinophil counts independently associate with wheeze and asthma events in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:821–827. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanania NA, Wenzel S, Rosén K, Hsieh HJ, Mosesova S, Choy DF, Lal P, Arron JR, Harris JM, Busse W. Exploring the effects of omalizumab in allergic asthma: an analysis of biomarkers in the EXTRA study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:804–811. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1414OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, Bleecker ER, Buhl R, Keene ON, Ortega H, Chanez P. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:651–659. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60988-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corren J, Lemanske RF, Hanania NA, Korenblat PE, Parsey MV, Arron JR, Harris JM, Scheerens H, Wu LC, Su Z, et al. Lebrikizumab treatment in adults with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1088–1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wenzel SE, Wang L, Pirozzi G. Dupilumab in persistent asthma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1276. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1309809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, Bush A, Castro M, Sterk PJ, Adcock IM, Bateman ED, Bel EH, Bleecker ER, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:343–373. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00202013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward H, Cooper BG, Miller MR. Improved criterion for assessing lung function reversibility. Chest. 2015;148:877–886. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.in ’t Veen JC, Beekman AJ, Bel EH, Sterk PJ. Recurrent exacerbations in severe asthma are associated with enhanced airway closure during stable episodes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1902–1906. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9906075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller MK, Lee JH, Blanc PD, Pasta DJ, Gujrathi S, Barron H, Wenzel SE, Weiss ST TENOR Study Group. TENOR risk score predicts healthcare in adults with severe or difficult-to-treat asthma. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:1145–1155. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00145105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, D’Agostino R, Jr, Castro M, Curran-Everett D, Fitzpatrick AM, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:315–323. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourdin A, Molinari N, Vachier I, Varrin M, Marin G, Gamez AS, Paganin F, Chanez P. Prognostic value of cluster analysis of severe asthma phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1043–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clemencon GH, Osterman PO. Hiatal hernia in bronchial asthma: the importance of concomitant pulmonary emphysema. Gastroenterologia. 1961;95:110–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayres JG, Miles JF. Oesophageal reflux and asthma. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:1073–1078. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09051073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konno A, Hoshino T, Togawa K. Influence of upper airway obstruction by enlarged tonsils and adenoids upon recurrent infection of the lower airway in childhood. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:1709–1716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busse WW, Holgate ST, Wenzel SW, Klekotka P, Chon Y, Feng J, Ingenito EP, Nirula A. Biomarker profiles in asthma with high vs low airway reversibility and poor disease control. Chest. 2015;148:1489–1496. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kew KM, Dahri K. Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) added to combination long-acting beta2-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids (LABA/ICS) versus LABA/ICS for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016:CD011721. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011721.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loymans RJ, Honkoop PJ, Termeer EH, Snoeck-Stroband JB, Assendelft WJ, Schermer TR, Chung KF, Sousa AR, Sterk PJ, Reddel HK, et al. Identifying patients at risk for severe exacerbations of asthma: development and external validation of a multivariable prediction model. Thorax. 2016;71:838–846. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McFadden EA, Woodson BT, Fink JN, Toohill RJ. Surgical treatment of aspirin triad sinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 1997;11:263–270. doi: 10.2500/105065897781446702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amar YG, Frenkiel S, Sobol SE. Outcome analysis of endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic sinusitis in patients having Samter’s triad. J Otolaryngol. 2000;29:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mastronarde JG, Anthonisen NR, Castro M, Holbrook JT, Leone FT, Teague WG, Wise RA American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers. Efficacy of esomeprazole for treatment of poorly controlled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1487–1499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holbrook JT, Wise RA, Gold BD, Blake K, Brown ED, Castro M, Dozor AJ, Lima JJ, Mastronarde JG, Sockrider MM, et al. Writing Committee for the American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers. Lansoprazole for children with poorly controlled asthma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:373–381. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, Baur X, Hall GL, Culver BH, Enright PL, Hankinson JL, Ip MS, Zheng J, et al. ERS Global Lung Function Initiative. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1324–1343. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]