Abstract

Rationale: Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) increase the risk of death and drive healthcare costs, but whether they accelerate loss of lung function remains controversial. Whether exacerbations in subjects with mild COPD or similar acute respiratory events in smokers without airflow obstruction affect lung function decline is unknown.

Objectives: To determine the association between acute exacerbations of COPD (and acute respiratory events in smokers without COPD) and the change in lung function over 5 years of follow-up.

Methods: We examined data on the first 2,000 subjects who returned for a second COPDGene visit 5 years after enrollment. Baseline data included demographics, smoking history, and computed tomography emphysema. We defined exacerbations (and acute respiratory events in those without established COPD) as acute respiratory symptoms requiring either antibiotics or systemic steroids, and severe events by the need for hospitalization. Throughout the 5-year follow-up period, we collected self-reported acute respiratory event data at 6-month intervals. We used linear mixed models to fit FEV1 decline based on reported exacerbations or acute respiratory events.

Measurements and Main Results: In subjects with COPD, exacerbations were associated with excess FEV1 decline, with the greatest effect in Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage 1, where each exacerbation was associated with an additional 23 ml/yr decline (95% confidence interval, 2–44; P = 0.03), and each severe exacerbation with an additional 87 ml/yr decline (95% confidence interval, 23–151; P = 0.008); statistically significant but smaller effects were observed in Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage 2 and 3 subjects. In subjects without airflow obstruction, acute respiratory events were not associated with additional FEV1 decline.

Conclusions: Exacerbations are associated with accelerated lung function loss in subjects with established COPD, particularly those with mild disease. Trials are needed to test existing and novel therapies in subjects with early/mild COPD to potentially reduce the risk of progressing to more advanced lung disease.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 00608764).

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, exacerbations, spirometry

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease worsen health status, drive healthcare costs, and are associated with mortality. Whether exacerbations accelerate lung function loss remains controversial, and no studies have adequately examined this question in patients with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or the effect of similar respiratory events in smokers without airflow obstruction.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are associated with accelerated loss of lung function, particularly in patients with mild disease. Similar acute respiratory events in smokers without airflow obstruction are not associated with greater FEV1 decline.

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) account for most COPD-related costs (1) and when frequent lead to marked reductions in health-related quality of life (2). Severe exacerbations requiring hospitalization also portend a poor prognosis, with 1- and 5-year mortality exceeding 20% and 50% (3–6). Although these impacts have been consistently reported, whether acute exacerbations impact the rate of decline of lung function over time remains uncertain. Although many COPD treatments reduce exacerbation frequency and some studies suggest that inhaled therapies may reduce FEV1 decline (7, 8), there is no information about the association between these two key disease features. Many smokers without COPD also suffer acute respiratory events that appear clinically similar to classic exacerbations in those with established COPD (9, 10). Whether such respiratory events accelerate lung function loss or lead to the development of COPD is unknown.

Previous studies have examined the relationship between acute respiratory illnesses and lung function decline in subjects with established COPD but the findings are not consistent (11–18). Although some have suggested a significant excess loss of FEV1 for each respiratory event (13), or in those with frequent events (15), others have reported minimal (12) or no relationship (18). Such disparate results may result from design differences including sample size, study duration, and exacerbation definitions. Most previous studies also focused on more advanced COPD; only the Lung Health Study included subjects with Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage 1 COPD (FEV1 >80% of predicted) and none included those without airflow obstruction (GOLD stage 0) or with a nonspecific or restrictive type spirometric pattern (preserved ratio impaired spirometry [PRISm]) (19, 20). Although the GOLD guidelines include prevention of exacerbations as a major treatment goal in patients with established COPD (3), there are uncertainties about the link between exacerbations and lung function loss, particularly in patients with mild airflow obstruction (21).

The COPDGene (Genetic Epidemiology of COPD) study enrolled current and former smokers and obtained spirometry and detailed respiratory illness history at the time of enrollment and captured exacerbations in longitudinal follow-up assessments over 5 years (22). The study provides a robust dataset to further understand how respiratory events relate to longitudinal FEV1 decline across a wide range of COPD severity and in smokers without COPD. We hypothesized that acute respiratory events would be associated with more rapid FEV1 decline in all GOLD stages.

Methods

Study Population and Assessments

COPDGene (NCT00608764) is a multicenter longitudinal observational cohort study that initially enrolled 10,300 participants (22). Subjects in the current analysis were the first 2,000 subjects who returned for a second COPDGene visit approximately 5 years after their initial visit. To minimize bias related to missing data, we also included baseline data for the 861 subjects who were more than 1 year late for their return visit or declined further participation sometime after their first visit. Written informed consent was obtained from subjects, and the study was approved by the institutional review boards of all 21 participating centers.

COPDGene participants were non-Hispanic white and African American current and former smokers with at least a 10 pack-year smoking history, with and without COPD (22). We excluded subjects with known lung diseases other than asthma, such as lung cancer, bronchiectasis, and interstitial lung disease. At baseline and at 5 years after the initial visit, spirometry was performed (Easy-One spirometer; NDD, Andover, MA) before and after administration of 180 μg of albuterol (via Aerochamber Activis, Parsippany, NJ). Bronchodilator reversibility was defined as at least 12% and 200-ml increase in FEV1 or FVC post-bronchodilator (23). COPD severity was assessed using spirometry criteria outlined by the GOLD guidelines with reference values from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (24, 25). GOLD stage 0 refers to current and former smokers without COPD, which although not included in the current GOLD guidelines, was used previously (26). Subjects with PRISm are current and former smokers with reduced FEV1 less than 80% predicted but normal FEV1/FVC ratio (>0.70) (19).

At baseline and follow-up, we performed high-resolution computed tomographic scans at full inspiration. Emphysema was estimated by the percentage of lung volume on the inspiratory computed tomographic with attenuation less than −950 HU (low-attenuation area, %LAA950insp) using 3D Slicer software (www.airwayinspector.org) (22).

Exacerbations (and acute respiratory events in those without established COPD) were defined as acute respiratory symptoms that required use of either antibiotics or systemic steroids; severe events were defined by the need for hospitalization (3). Self-reported acute respiratory event data were collected at 6-month intervals, via an automated telephony system, web-based survey, or telephone contact throughout the follow-up period between visits 1 and 2 (27).

Statistical Analyses

Linear mixed models were used to fit FEV1 longitudinally, stratified by GOLD group. Primary predictors included visit (baseline and follow-up), acute respiratory events/exacerbations, and their interaction. Covariates included baseline race, sex, percent emphysema, and smoking status (continuing, intermittent, or former based on longitudinal follow-up data) as time-invariant variables; and weight, age, height, and bronchodilator response as time-varying variables. Squared terms for age and height were also included in the models. An unstructured covariance structure was used for repeated measures. Total number of exacerbations, number of severe exacerbations, and binary categorization of exacerbations (none vs. at least one) were used as predictors in separate models. Data from subjects that either completed both visits (completers) or only completed visit 1 and were either overdue by at least 1 year or requested no further contact (late) were used to fit models. Subjects with visit 1 data but who died before visit 2 (deceased) were not included in primary analyses. For more details, see the online supplement. All statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

For subjects completing both visits, the average time between visit 1 and visit 2 was 5.25 years. Clinical characteristics of the primary analytic cohort are shown in Table 1. Subjects in the PRISm and GOLD stage 0 groups were slightly younger at their baseline visit than those with established airflow obstruction, were more often female and African American, and exhibited less bronchodilator responsiveness. Current smoking rates declined with increasing severity of COPD, whereas the extent of emphysema and use of inhaled medications was greater in those with more airflow obstruction. As previously published, the use of inhaled medications was as or more common in PRISm subjects than in those with GOLD stage 0/1 disease (20).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Subjects in the Cohort and Analysis (Completers or Late)

| PRISm | GOLD 0 | GOLD 1 | GOLD 2 | GOLD 3 | GOLD 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 318 | 1,223 | 250 | 580 | 357 | 133 |

| Completers | 225 | 878 | 185 | 412 | 229 | 71 |

| Late | 93 | 345 | 65 | 168 | 128 | 62 |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 58.2 (8.1) | 57.6 (8.8) | 63.7 (8.8) | 63.1 (8.6) | 64.3 (8.1) | 63.3 (7.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 171 (54) | 640 (52) | 109 (44) | 279 (48) | 171 (48) | 58 (44) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 173 (54) | 775 (63) | 203 (81) | 440 (76) | 286 (80) | 110 (83) |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||||||

| Current | 107 (34) | 382 (31) | 65 (26) | 124 (21) | 34 (10) | 5 (4) |

| Former | 126 (40) | 517 (42) | 128 (51) | 319 (55) | 226 (63) | 98 (74) |

| Intermittent | 85 (27) | 324 (26) | 57 (23) | 137 (24) | 97 (27) | 30 (23) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 32.0 (6.9) | 28.8 (5.8) | 27.2 (5.2) | 28.8 (6.0) | 28.1 (6.2) | 26.7 (5.7) |

| FEV1 at baseline visit, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Liters | 2.05 (0.49) | 2.84 (0.68) | 2.62 (0.65) | 1.86 (0.50) | 1.13 (0.29) | 0.68 (0.18) |

| % predicted | 70.6 (8.0) | 97.7 (11.3) | 91.4 (9.1) | 64.7 (8.5) | 40.4 (5.6) | 23.4 (4.3) |

| COPD medications, n (%) | ||||||

| ICS only | 26 (8) | 18 (1) | 10 (4) | 41 (7) | 45 (13) | 28 (22) |

| LAMA | 26 (8) | 28 (2) | 23 (9) | 158 (28) | 184 (52) | 88 (67) |

| ICS and LABA | 44 (14) | 42 (3) | 23 (9) | 169 (30) | 192 (54) | 83 (63) |

| LABA only | 5 (2) | 5 (0.4) | 2 (1) | 34 (6) | 29 (8) | 23 (18) |

| Emphysema, mean (SD) | 1.9 (2.9) | 2.6 (3.0) | 7.2 (6.8) | 8.7 (8.2) | 18.2 (12.9) | 25.3 (12.8) |

| BDR, L, mean (SD) | 0.13 (0.34) | 0.09 (0.28) | 0.25 (0.44) | 0.36 (0.48) | 0.38 (0.49) | 0.28 (0.45) |

Definition of abbreviations: BDR = bronchodilator responsiveness; BMI = body mass index; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; ICS = inhaled corticosteroids; LABA = long-acting β-agonists; LAMA = long-acting antimuscarinic; PRISm = preserved ratio impaired spirometry.

Sample sizes available for analysis for PRISm, GOLD 0, GOLD 1, GOLD 2, GOLD 3, and GOLD 4 were as follows: 312, 1,209, 248, 560, 352, and 127 for ICS only; 312, 1,213, 249, 566, 355, and 132 for ICS and LABA; 312, 1,211, 248, 566, 354, and 131 for LAMA; 309, 1,209, 248, 562, 352, and 128 for LABA; 299, 1,156, 240, 550, 333, and 119 for emphysema; and 314, 1,205, 248, 576, 355, and 132 for BDR, respectively. For all other variables, sample sizes are as given in the first row.

Of the initial 10,300 enrolled subjects, 3,521 were due for visit 2 at the time of analysis. Of these, 2,000 subjects were in the completer subgroup. There were 861 and 660 in the late and deceased subgroups, respectively. Subgroups were generally similar except for more former smokers among the completers in PRISm and GOLD stage 0–1 groups compared with late and deceased, and lower baseline mean FEV1 in GOLD stage 2–4 for deceased compared with completers in GOLD stage 2–4 (see Table E1 in the online supplement). The proportion of late subjects was similar across GOLD groups (20% for GOLD stage 4 and 23–26% for all other GOLD groups including PRISm). The number of deaths in the GOLD stage 0 through stage 4 groups were 115 (9%), 27 (10%), 127 (18%), 151 (30%), and 174 (57%), respectively, and 66 (17%) for PRISm subjects.

Analysis of the exacerbation/acute respiratory event frequency showed that exacerbations were common in all groups (Table 2), with more than a third (36.7%) of subjects reporting events during follow-up. Both the proportion of subjects who suffered any event and the annualized rates increased with worsening lung function. Severe events requiring hospitalization were common, even in the PRISm and GOLD stage 0 groups (at least once during follow-up in 14% of PRISm, and 8% of GOLD stage 0), although such events increased markedly in more advanced COPD (at least once during follow-up in 10% of GOLD stage 1, 24% of GOLD stage 2, 42% of GOLD stage 3, and 47% of GOLD stage 4).

Table 2.

Exacerbation Distributions and Annualized Rates for the Analytic Cohort Based on Longitudinal Follow-up Surveys, by GOLD Stage

| |

PRISm |

GOLD 0 |

GOLD 1 |

GOLD 2 |

GOLD 3 |

GOLD 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 282 | 1,111 | 230 | 544 | 339 | 125 |

| All exacerbations | ||||||

| ≥1 event during follow-up, % | 30.5 | 21.5 | 27.4 | 46.5 | 70.2 | 69.6 |

| Percentage with average of 1 or more per year | 12.8 | 4.1 | 7.0 | 12.5 | 28.6 | 35.2 |

| Percentage with average of 2 or more per year | 3.9 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 4.4 | 10.0 | 12.0 |

| Mean rate, per year | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.36 | 0.72 | 0.89 |

| Severe exacerbations | ||||||

| ≥1 event during follow-up, % | 13.5 | 8.1 | 10.0 | 24.1 | 42.2 | 47.2 |

| Percentage with average of 1 or more per year | 4.6 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 5.6 | 11.2 |

| Percentage with average of 2 or more per year | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.6 |

| Mean rate, per year | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.31 |

Definition of abbreviations: GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; PRISm = preserved ratio impaired spirometry.

Longitudinal follow-up surveys were available on 1,937 of 2,000 completers and 694 of 861 late subjects in the analytic cohort, combined above.

Among subjects without exacerbations/acute respiratory events, we found rates of FEV1 change between +5 and −25 ml/yr (Table 3), factoring out expected changes caused by aging and other time-varying covariates (height, weight, and bronchodilator responsiveness). The greatest rate of FEV1 decline in absence of exacerbations occurred in those with GOLD stage 1 and 2, with mean losses of 25 and 19 ml/yr, respectively. For GOLD stage 0 subjects, there was no difference in the rate of FEV1 decline between those who reported significant dyspnea (Medical Research Council ≥2) and those who did not (Medical Research Council <2) (13 ml/yr vs. 9 ml/yr; P = 0.30). There was also no difference in the relationship between exacerbations and excess decline in FEV1 based on Medical Research Council classification (P = 0.16 for interaction) among GOLD stage 0 subjects.

Table 3.

Effect of Each Exacerbation/Acute Respiratory Event on Rate of FEV1 Decline

| Subject Group | Change in FEV1 (ml/yr) (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exacerbations/Acute Respiratory Events of Any Severity |

Severe Exacerbations/Acute Respiratory Events |

|||

| Change in Those with No Exacerbations | Excess Change, per Exacerbation of Any Severity | Change in Those with No Severe Exacerbations | Excess Change, per Severe Exacerbation | |

| PRISm | 5 (−4 to 14) | −6 (−15 to 4) | 5 (−4 to 14) | −17 (−37 to 2) |

| GOLD 0 | −9 (−13 to −4) | −7 (−15 to 2) | −9 (−14 to −5) | −7 (−27 to 13) |

| GOLD 1 | −25 (−34 to −15) | −23 (−44 to −2) | −26 (−35 to −16) | −87 (−151 to −23) |

| GOLD 2 | −19 (−26 to −11) | −10 (−20 to −1) | −21 (−28 to −14) | −20 (−40 to 1) |

| GOLD 3 | −8 (−17 to 0) | −8 (−15 to −1) | −10 (−18 to −3) | −20 (−36 to −4) |

| GOLD 4 | −4 (−16 to 8) | 0 (−9 to 8) | −2 (−13 to 8) | −9 (−29 to 12) |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; PRISm = preserved ratio impaired spirometry.

Estimates reflect average changes after factoring out expected changes caused by time-varying covariates (age, height, weight, and bronchodilator responsiveness). For example, the change in FEV1 for a GOLD stage 1 subject with one, two, or three exacerbations over the follow-up period can be estimated by adding the excess decline per exacerbation event (−23 ml/yr) to the rate in those without events (−25 ml/yr), yielding a final annual rate of −48 ml/yr, −71 ml/yr, and −94 ml/yr.

Number of subjects available for analysis for PRISm, GOLD 0, GOLD 1, GOLD 2, GOLD 3, and GOLD 4 groups were 267, 1,055, 227, 515, 320, and 113, respectively; number of records available for analysis for the respective groups were 481, 1,891, 404, 913, 543, and 183. Some records were not usable because of missing data for bronchodilator responsiveness, emphysema rate, exacerbations, or some combination of these (see Table 1 and online supplement for more details).

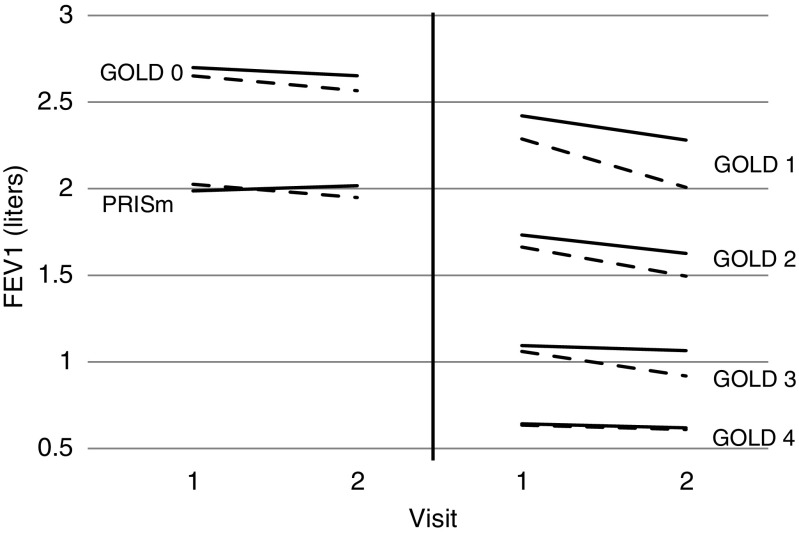

Exacerbations/acute respiratory events of any severity were associated with statistically significant excess FEV1 decline in GOLD stage 1, 2, and 3 subjects. The magnitude of effect was largest in GOLD stage 1 subjects, where each exacerbation was associated with an additional 23 ml/yr decline in FEV1. We also found that severe exacerbations were associated with greater declines in FEV1 and again the strongest effects were seen in GOLD stage 1 subjects, where each severe exacerbation was associated with an additional 87 ml/yr decline in FEV1 (Table 3, Figure 1). There was no statistically significant excess decline in FEV1 for each additional exacerbation/acute respiratory event of any severity in any of the PRISm, GOLD stage 0, or GOLD stage 4 groups, although the GOLD stage 4 data may be impacted by survivor bias as discussed later. Our primary model used completers and visit 1 data for late subjects; additional models were fit for completers only (see online supplement) and for completers and visit 1 data for late and deceased subjects combined (data not shown) and yielded similar results.

Figure 1.

Estimated FEV1 changes by Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) group and severe exacerbations status. Estimates were obtained from linear mixed model fits (see Statistical Analyses section) for the completer and late subjects. The plot demonstrates that those with at least one severe exacerbation (dashed lines) had faster declines in FEV1, on average, compared with those that did not (solid lines), for each GOLD group. PRISm = preserved ratio impaired spirometry.

As expected, we found a steeper average decline in FEV1 among current and intermittent smokers (9-ml decline) than among former smokers (2-ml decline; P = 0.005 for difference). Because smoking cessation slows the rate of FEV1 decline, we extended models by including smoking status as an effect modifier; models included up to three-way interaction terms with time, occurrence of severe exacerbations (defined as none vs. at least one), and smoking status (former vs. current or intermittent). For GOLD stage 2 and 3 subjects there was a steeper decline in FEV1 over time for current/intermittent smokers with a severe acute exacerbation versus subjects that were either former smokers or did not suffer a severe acute exacerbation or both (57 ml/yr vs. 18 ml/yr; P < 0.0001 for GOLD stage 2; 39 ml/yr vs. 10 ml/yr; P = 0.008 for GOLD stage 3). Similar results were found when considering exacerbations of any type.

Discussion

The results of this study of more than 2,000 well-characterized current and formers smokers followed for 5 years demonstrate that acute exacerbations are associated with accelerated declines in FEV1 in those with established COPD, particularly in those with mild (GOLD stage 1) disease and when the exacerbations are severe. By contrast, although many current and former smokers without airflow obstruction have respiratory impairment and suffer exacerbation-like respiratory events (9, 10), we found no evidence that these accelerate lung function loss. Collectively, these findings support the hypothesis that acute exacerbations contribute to COPD progression, particularly in those with disease that is initially mild.

These findings provide novel information in the long-standing debate about the role of bronchitic episodes in the pathogenesis of COPD associated with tobacco products. In the 1970s, the original West London longitudinal spirometry study by Fletcher and Peto (11) demonstrated no relationship between bronchial infections and rate of decline in FEV1. By contrast, a contemporaneous cohort in the United States did find a relationship between lower respiratory illness frequency and FEV1 decline among 150 subjects who had COPD at entry (14). Subsequent longitudinal analysis from the Lung Health Study suggested that in continuous and intermittent smokers, each lower respiratory infection reported was associated with an additional 7 ml/yr decline in FEV1, although no effect was seen in those who had quit smoking (13). Donaldson and colleagues (15) found a similar estimate of additional lung function loss (8 ml/yr) in subjects with frequent exacerbations (defined as >2.92 exacerbations/yr) as compared with those without, although the study was small (n = 109) and the exacerbations were based on diary records and thus mild in many cases. Contradictory data came from the 3-year ECLIPSE study, which reported only a 2 ml/yr greater annual decline in FEV1 per exacerbation (although no GOLD stage 1 subjects were included) (12), whereas the 5-year Hokkaido COPD cohort study found no relationship between exacerbations and FEV1 decline, although the population enrolled was also quite small (n = 268) (18). Our analysis confirms a relationship between exacerbations and lung function loss in subjects with GOLD stage 2 and 3 disease and adds convincing data that the effect is greatest in subjects with more mild COPD (GOLD stage 1) and for more severe events.

Our observation that lung function loss related to exacerbations was greatest in those with GOLD stage 1 disease is novel and has several potential implications for COPD care. First is the possibility that preventing exacerbations in this subpopulation could reduce the risk of developing severe COPD, an important hypothesis that should motivate randomized trials. The possibility that mild-to-moderate disease may be more amenable to therapy than severe airflow obstruction is supported by the UPLIFT study, which suggested that exacerbations, mortality, and perhaps FEV1 decline were all reduced by tiotropium in subjects with FEV1 greater than 60% (28). The link between exacerbations and lung function decline has been questioned, in part because many drugs reduce the risk of exacerbation but none have been definitively shown to reduce FEV1 loss. This could be explained by the fact that earlier studies mostly excluded GOLD stage 1 COPD.

An unanticipated finding was the lack of evidence that acute respiratory events impact lung function loss in subjects with GOLD stage 0 disease or PRISm. Both of these groups have been demonstrated to have significant respiratory symptoms and impairment, in some cases greater than subjects with GOLD stage 1 COPD, and as we observed, they are also often treated with long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids despite no evidence to support that practice (9, 10, 19, 29). We can only speculate about why no relationships between acute respiratory events and FEV1 decline were observed in these subjects. One possibility is that whatever mechanisms protect them from the development of COPD, such as enhanced antiinflammatory or reparative capacity, also protect against lung function loss with episodes of bronchitis. A second possibility that requires additional testing is that acute respiratory events in GOLD stage 0 subjects are fundamentally different from those in subjects with established COPD, a possibility supported by the observation that patients with COPD but not healthy smokers had significant increases in bacterial colonization after experimental respiratory rhinoviral infection (30).

As shown in COPDGene (9), and recently confirmed in the SPIROMICS (Subpopulations and InteRmediate Outcome Measures In COPD Study) cohort (29), the risk of acute respiratory events in symptomatic GOLD 0 current and former smokers often exceeds the risk in patients with established COPD. Additional follow-up of SPIROMICS participants should allow further analyses to either confirm or refute our findings. PRISm subjects have increased emphysema and airway wall thickness, relative to smokers with normal spirometry, but have several distinct features compared with those with typical COPD including less bronchodilator responsiveness and greater body mass index (19). PRISm has also proven to be heterogeneous with several phenotypic clusters, each likely the result of different pathophysiologic processes (20). This diversity also likely impacts the nature and impact of acute respiratory events in different PRISm subjects and requires further study.

Although our study was not designed to confirm the pathophysiologic link between exacerbations, their severity, and lung function decline, and we cannot assign directional causality, several plausible mechanisms could be proposed. First, exacerbations are associated with significant pulmonary inflammation including activation of matrix metalloproteinases (31) and increased hyaluronidase activity (32), which may trigger a number of permanent changes to the lung parenchyma including airway fibrosis and additional loss of alveolar tissue. Second, some subjects who suffer prolonged exacerbations may not fully recover before the next episode begins leading to a progressive deterioration with each event and faster lung function loss over time (33). Greater increases in sputum IL-8 and IL-6 from baseline to Day 7 of an exacerbation predict a delayed recovery, potentially linking severe exacerbations to more pronounced inflammation and larger lung function decline (34).

Strengths of our study include its large, multicenter sample, longitudinal study design, use of standardized post-bronchodilator spirometry, our careful collection of exacerbation data over a 5-year period, and the inclusion of large numbers of GOLD stage 0 and PRISm subjects. The study is limited by the loss of some subjects to follow-up, and because it was observational in nature, we cannot assign causality between exacerbations and loss of lung function. Missing data poses issues with many longitudinal studies, and we attempted to account for potential bias in estimates caused by missing data and understand differences between completers and Dropouts by examining their baseline characteristics. We did find completers, late, and deceased subjects to be fairly similar in regards to demographic characteristics and baseline lung function. In addition, our primary analytical approach allowed FEV1 decline estimates to be adjusted based on visit 1 data for subjects who were late for visit 2.

Still, there is the potential that data were missing not at random. In particular, it is possible that late subjects had a faster decline in FEV1 than completers, and we have no information about progression in the former group because there were only two visits requiring spirometry (see online supplement for further discussion.) We do not consider subjects that had COPD-related deaths before they could complete visit 2 as having missing data, but rather, as having an alternative outcome to an FEV1 measurement (although subjects that died before visit 2 may also have had a steeper average FEV1 decline after visit 1 than completers). It is therefore important to consider overall survival and FEV1 decline for living subjects to portray a more complete picture of disease progression and note that although the declines in FEV1 diminished with increasing GOLD stage (and were in fact not significant in GOLD stage 4), survival also decreased. Although information on final cause of death was unavailable, we anticipate many were directly or indirectly related to COPD.

Our study is also limited by the collection of spirometry at only two time points, approximately 5 years apart. Although analyses of FEV1 decline has traditionally relied on more frequent collection of data, we note that in the Lung Health Study, the slopes of FEV1 decline estimated over five annual tests was not different from that measured with only two time points 6 years apart (35). In addition, we did not collect data about how exacerbations were treated (antibiotics, systemic corticosteroids, or both) and thus cannot compare the relative impact of exacerbation treatment on lung function loss.

In summary, we provide novel evidence that exacerbations accelerate lung function loss in subjects with established COPD, particularly when these events are severe and occur in those with mild disease. These findings emphasize the need for clinical trials in early/mild COPD, to test whether preventing exacerbations could reduce progression to more advanced lung disease.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL089897 and R01HL089856. COPDGene is also supported by the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an Industry Advisory Board comprised of AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Siemens, Sunovion, and GlaxoSmithKline. The industry funders had no role in study design, collection/analysis/interpretation of the data, preparation of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. This material is also the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Minneapolis VA and VA Ann Arbor Health Care Systems. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the United States Government, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the authors’ affiliated institutions, or the funders of the study.

Author Contributions: Wrote the manuscript, M.T.D., K.M.K., M.J.S., and B.J.M. Study design, M.T.D., K.M.K., M.J.S., G.J.C., R.P.B., S.E.R., and B.J.M. Performed the statistical analyses, M.J.S. Revised the manuscript for critical intellectual content, A.A., S.P.B., R.P.B., G.J.C., J.L.C., N.A.H., H.N., N.P., S.E.R., E.S.W., G.R.W., J.M.W., and C.H.W.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1014OC on August 24, 2016

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Dalal AA, Christensen L, Liu F, Riedel AA. Direct costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among managed care patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:341–349. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S13771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, Bestall JC, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1418–1422. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9709032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Fabbri LM, Martinez FJ, Nishimura M, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:347–365. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soler-Cataluña JJ, Martínez-García MA, Román Sánchez P, Salcedo E, Navarro M, Ochando R. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60:925–931. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.040527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, Sutherland ER, Welsh C, Make B. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2007;132:1748–1755. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blasi F, Cesana G, Conti S, Chiodini V, Aliberti S, Fornari C, Mantovani LG. The clinical and economic impact of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cohort of hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vestbo J, Anderson JA, Brook RD, Calverley PM, Celli BR, Crim C, Martinez F, Yates J, Newby DE SUMMIT Investigators. Fluticasone furoate and vilanterol and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with heightened cardiovascular risk (SUMMIT): a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1817–1826. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celli BR, Thomas NE, Anderson JA, Ferguson GT, Jenkins CR, Jones PW, Vestbo J, Knobil K, Yates JC, Calverley PM. Effect of pharmacotherapy on rate of decline of lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the TORCH study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:332–338. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1869OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowler RP, Kim V, Regan E, Williams AA, Santorico SA, Make BJ, Lynch DA, Hokanson JE, Washko GR, Bercz P, et al. COPDGene investigators. Prediction of acute respiratory disease in current and former smokers with and without COPD. Chest. 2014;146:941–950. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regan EA, Lynch DA, Curran-Everett D, Curtis JL, Austin JH, Grenier PA, Kauczor HU, Bailey WC, DeMeo DL, Casaburi RH, et al. Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) Investigators. Clinical and radiologic disease in smokers with normal spirometry. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1539–1549. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. BMJ. 1977;1:1645–1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vestbo J, Edwards LD, Scanlon PD, Yates JC, Agusti A, Bakke P, Calverley PM, Celli B, Coxson HO, Crim C, et al. ECLIPSE Investigators. Changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 second over time in COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1184–1192. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanner RE, Anthonisen NR, Connett JE Lung Health Study Research Group. Lower respiratory illnesses promote FEV(1) decline in current smokers but not ex-smokers with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the lung health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:358–364. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.3.2010017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanner RE, Renzetti AD, Jr, Klauber MR, Smith CB, Golden CA. Variables associated with changes in spirometry in patients with obstructive lung diseases. Am J Med. 1979;67:44–50. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)90072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57:847–852. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.10.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halpin DM, Decramer M, Celli B, Kesten S, Liu D, Tashkin DP. Exacerbation frequency and course of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:653–661. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S34186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makris D, Moschandreas J, Damianaki A, Ntaoukakis E, Siafakas NM, Milic Emili J, Tzanakis N. Exacerbations and lung function decline in COPD: new insights in current and ex-smokers. Respir Med. 2007;101:1305–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki M, Makita H, Ito YM, Nagai K, Konno S, Nishimura M Hokkaido COPD Cohort Study Investigators. Clinical features and determinants of COPD exacerbation in the Hokkaido COPD cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1289–1297. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00110213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan ES, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Regan EA, Make BJ, Lynch DA, Crapo JD, Silverman EK COPDGene Investigators. Clinical and radiographic predictors of GOLD-unclassified smokers in the COPDGene study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:57–63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0021OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan ES, Castaldi PJ, Cho MH, Hokanson JE, Regan EA, Make BJ, Beaty TH, Han MK, Curtis JL, Curran-Everett D, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Epidemiology, genetics, and subtyping of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) in COPDGene. Respir Res. 2014;15:89. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0089-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, Hanania NA, Criner G, van der Molen T, Marciniuk DD, Denberg T, Schünemann H, Wedzicha W, et al. American College of Physicians; American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179–191. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Make B, Lynch DA, Beaty TH, Curran-Everett D, Silverman EK, Crapo JD. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD. 2010;7:32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soriano JB, Lamprecht B, Ramírez AS, Martinez-Camblor P, Kaiser B, Alfageme I, Almagro P, Casanova C, Esteban C, Soler-Cataluña JJ, et al. Mortality prediction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease comparing the GOLD 2007 and 2011 staging systems: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:443–450. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS GOLD Scientific Committee. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1256–1276. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2101039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart JI, Moyle S, Criner GJ, Wilson C, Tanner R, Bowler RP, Crapo JD, Zeldin RK, Make BJ, Regan EA For The COPDgene Investigators. Automated telecommunication to obtain longitudinal follow-up in a multicenter cross-sectional COPD study. COPD. 2012;9:466–472. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.690010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tashkin DP, Celli BR, Decramer M, Lystig T, Liu D, Kesten S. Efficacy of tiotropium in COPD patients with FEV1 ≥ 60% participating in the UPLIFT trial. COPD. 2012;9:289–296. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.656211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodruff PG, Barr RG, Bleecker E, Christenson SA, Couper D, Curtis JL, Gouskova NA, Hansel NN, Hoffman EA, Kanner RE, et al. SPIROMICS Research Group. Clinical significance of symptoms in smokers with preserved pulmonary function. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1811–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molyneaux PL, Mallia P, Cox MJ, Footitt J, Willis-Owen SA, Homola D, Trujillo-Torralbo MB, Elkin S, Kon OM, Cookson WO, et al. Outgrowth of the bacterial airway microbiome after rhinovirus exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1224–1231. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0341OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papakonstantinou E, Karakiulakis G, Batzios S, Savic S, Roth M, Tamm M, Stolz D. Acute exacerbations of COPD are associated with significant activation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 irrespectively of airway obstruction, emphysema and infection. Respir Res. 2015;16:78. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0240-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papakonstantinou E, Roth M, Klagas I, Karakiulakis G, Tamm M, Stolz D. COPD exacerbations are associated with proinflammatory degradation of hyaluronic acid. Chest. 2015;148:1497–1507. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donaldson GC, Law M, Kowlessar B, Singh R, Brill SE, Allinson JP, Wedzicha JA. Impact of prolonged exacerbation recovery in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:943–950. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2269OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perera WR, Hurst JR, Wilkinson TM, et al. Inflammatory changes, recovery and recurrence at COPD exacerbation. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:527–534. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00092506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, Altose MD, Bailey WC, Buist AS, Conway WA, Jr, Enright PL, Kanner RE, O’Hara P, et al. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health Study. JAMA. 1994;272:1497–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]