ABSTRACT

Healthcare Workers (HCWs) have an increased risk both to acquire and to spread vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs) both to their colleagues and, especially, to vulnerable patients. The prevention of occupational hazards among HCWs is based on proper adoption of the standard and additional precautions, immunizations, and secondary preventive measures, such as post-exposure prophylaxis. Moreover, HCWs are often referred to as the most trusted source of vaccine-related information for their patients. In the present article, we report the findings of a cross-sectional study investigating the compliance to vaccinations among HCWs employed at the Obstetric Unit of a regional acute-care University Hospital in Northern Italy. Furthermore, a systematic review of the literature for some VPDs (i.e., HBV, measles, rubella, varicella and influenza) was performed, over a 17-year period, in order to update the socio-demographic and professional characteristics, the susceptibility status and the vaccination rates among HCWs in Italy.

KEYWORDS: hepatitis B virus, influenza, measles, rubella, varicella, healthcare workers, adherence, healthcare surveillance program, vaccination rates, vaccines

Introduction

World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that all over the world about 59 million Healthcare Workers (HCWs) are potentially exposed every day to multiple occupational biological hazards, working with infectious patients and contaminated fluids and materials (i.e., body fluids, medical supplies and equipment, environment).1 It is well known that susceptible HCWs have an increased risk, both to acquire and spread serious infectious diseases to vulnerable patients and colleagues, compare with the general population.2 Moreover, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) underlines that these professionals are often referred to as the most trusted source of vaccine-related information for their patients and colleagues: it is crucial to improve their knowledge and confidence in vaccination practices and to engage them in activities targeting the phenomenon of the so-called “vaccine hesitancy.”3

In Italy, current legislation imposes proper assessment and management of the biological risk in different occupational settings, particularly the healthcare services: in this scenario, effective preventive measures and protection devices, including immune-prophylaxis, are recommended by the National Health Authorities and the Scientific Societies. Indeed, several safe and effective vaccines are available to protect HCWs,4 such as those against hepatitis B virus (HBV), measles, rubella, varicella, influenza, pertussis, and meningococcal diseases. The Italian National Vaccination Plan (PNPV 2012–2014) strongly recommended immunization of HCWs with monovalent and combined vaccines - i.e., HBV recombinant vaccine, measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine, varicella vaccine, BCG vaccine, diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis (dTap) vaccine, and flu vaccine – with indications for use tailored to address the occupational risks.5

In this scenario, Healthcare Surveillance Programs in Italy routinely monitor healthcare professionals to identify susceptible individuals and to properly provide available vaccines, administered either as primary cycles or booster doses.2

Despite the above mentioned issues, several Authors have reported suboptimal immunization rates for some relevant vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) among HCWs in most of Western Countries, including Italy, even in professionals at high-risk of exposure to hazardous biological agents, such as those employed in obstetric or neonatology departments:5-10 this issue is of particular meaning also taking into account the evidence of nosocomial transmission, as reported in recent reports.9-12

Here below, we report the findings of a cross-sectional study investigating vaccination compliance to vaccinations among HCWs at the Obstetric Unit of a regional acute-care University Hospital in Northern Italy. Furthermore, a systematic review of the literature for some VPDs (i.e., HBV, measles, rubella, varicella and influenza) was performed, over a 17-year period, in order to update the socio-demographic and professional characteristics, the susceptibility status and the vaccination rates among HCWs in Italy.

Results

Cross sectional study

In the cross sectional study performed among HCWs employed at the Obstetric Unit of the University Hospital, IRCCS AOU San Martino – IST of Genoa, out of the 187 HCWs who matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 171 (92.4%) entered the study and were interviewed by 2 trained professionals, using a structured questionnaire.

The characteristics of the study population, together with the main results of the survey, are reported in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (n = 171).

| Professional categories | Subjects n (%) | Female n (%) | Age (years) mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obstetricians and gynaecologists | 19 (11.1) | 5 (16.3) | 59.3 ± 5.8 |

| Residents in Obstetrics and Gynecology | 23 (13.5) | 22 (95.7) | 28.7 ± 1.3 |

| Anaesthesiologists | 10 (5.8) | 6 (60.0) | 50.5 ± 4.5 |

| Neonatologists | 11 (6.4) | 6 (54.5) | 53.0 ± 10.9 |

| General nurses | 38 (22.2) | 37 (97.4) | 48.7 ± 6.3 |

| Midwives | 28 (16.4) | 28 (100) | 48.3 ± 7.8 |

| Health care assistants | 10 (5.8) | 7 (70.0) | 52.3 ± 7.8 |

| Neonatal nurses | 32 (18.7) | 30 (37.5) | 49.0 ± 6.7 |

SD: Standard Deviation

Table 2.

Previous history of Vaccine Preventable Diseases and immunization status among Healthcare Workers of the Obstetric Unit of the referral adult acute-care University hospital of Genoa, Liguria Region, Italy, according to professional category.

| Obstetricians and gynaecologistsn (%) | Residents in Obstetrics and Gynecologyn (%) | Anesthesiologistsn (%) | Neonatologistsn (%) | General nursesn (%) | Midwivesn (%) | Health care assistantsn (%) | Neonatal nursesn (%) | Total(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects included | 19 | 23 | 10 | 11 | 38 | 28 | 10 | 32 | 171 |

| Rubella | |||||||||

| Positive history | 14 (73.7) | 16 (69.6) | 7 (70.0) | 6 (54.5) | 29 (76.3) | 17 (60.7) | 6 (60.0) | 17 (53.1) | 112(65.5) |

| Previous vaccination | 0 (0) | 4 (17.4) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (9.1) | 7 (18.4) | 5 (17.9) | 3 (30.0) | 6 (18.7) | 27(15.8) |

| Not known | 5 (26.3) | 3 (13.1) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (5.3) | 6 (7.1) | 1 (10.0) | 9 (21.9) | 32(18.7) |

| HBV | |||||||||

| Positive history | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Previous vaccination | 16 (84.2) | 18 (78.3) | 7 (70.0) | 8 (72.7) | 34 (89.5) | 25 (89.3) | 5 (50.0) | 23 (71.9) | 136(79.5) |

| Not known | 3 (15.8) | 5 (21.7) | 3 (30.0) | 3 (27.3) | 4 (10.5) | 3 (10.7) | 5 (50.0) | 9 (28.1) | 35(20.5) |

| Varicella | |||||||||

| Positive history | 17 (89.4) | 18 (78.3) | 4 (40.0) | 11 (100) | 30 (78.9) | 24 (85.7) | 8 (80.0) | 27 (84.4) | 139(81.3) |

| Previous vaccination | 1 (5.3) | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (9.4) | 8(4.7) |

| Not known | 1 (5.3) | 3 (13.0) | 6 (60.0) | 0 (0) | 7 (18.4) | 3 (10.7) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (6.2) | 24(14) |

| Measles | |||||||||

| Positive history | 10 (52.6) | 9 (39.2) | 5 (50.0) | 7 (63.6) | 25 (65.8) | 15 (53.6) | 7 (70.0) | 16 (50.0) | 94(54.9) |

| Previous vaccination | 3 (15.8) | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (7.9) | 4 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.3) | 15(8.8) |

| Not known | 6 (31.5) | 11 (47.8) | 5 (50.0) | 4 (36.4) | 10 (26.3) | 9 (32.1) | 3 (30.0) | 14 (43.7) | 62(36.3) |

| Influenza* | |||||||||

| Performed | 6 (31.6) | 7 (30.4) | 3 (30.0) | 6 (54.5) | 8 (21.1) | 5 (17.9) | 2 (20.0) | 7 (21.9) | 44(25.7) |

| Not performed | 13 (60.4) | 16 (69.6) | 7 (70.0) | 5 (45.5) | 30 (78.9) | 23 (82.1) | 8 (80.0) | 25 (78.1) | 127(74.3) |

HBV: Hepatitis B virus;

During the previous year.

Systematic review

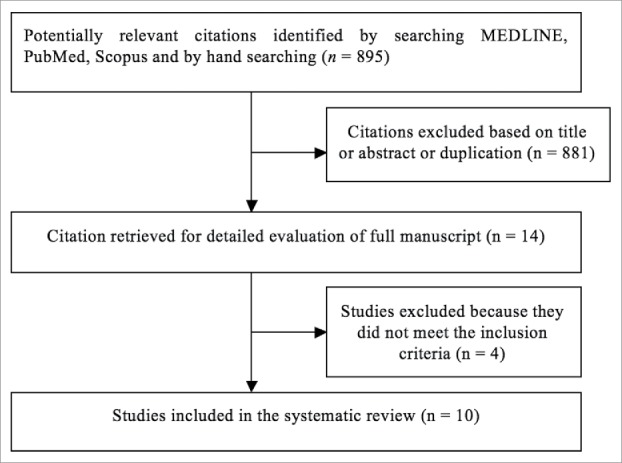

The database search yielded 895 possible citations. From reviewing the title or abstract, 885 products were excluded, as they did not meet the selection criteria, and a total of 10 studies were finally selected for analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the search strategy, screening, eligibility and inclusion criteria.

The main characteristics of the original articles included in the review are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the main characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review.

| Author | Study design | Year | N° | Aim of the study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fortunato et al.13 | Retrospective | 2009–2011 | 2198 | To assess levels of immunization and factors influencing adherence to vaccinations needed for HCWs in Puglia region. |

| Stroffolini et al.14 | Retrospective | 2006 | 1632 | To assess the vaccination coverage against HBV in HCWs. |

| Copello et al.15 | Prospective | 2014 | 2661 | To assess the risk of healthcare associated infections in HCWs of a Sardinian Local Health Authority |

| Campagna et al.16 | Prospective | 2013 | 32* | To investigate whether, how, and which vaccination underwent Sardinia Health Care Workers (HCWs) and the variability of policies in different Hospital Health Managements of the whole region |

| Campagna et al.17 | Retrospective | 2009–2010 | 32196 | To evaluate the risk assessment, health surveillance and fitness for work of HCWs exposed to rubella, measles, varicella and mumps. |

| Cologni et al.18 | Retrospective | 2007–2012 | 4000 | To determine the percentage of susceptible HCWs to rubella, measles, varicella and mumps infection. |

| Fedeli et al.19 | Retrospective | 1998–2001 | 333 | To determine the proportion of workers employed in high-risk healthcare areas who are susceptible to measles, mumps, rubella or varicella. |

| Porru et al.20 | Retrospective | 2004–2007 | 4000 | To evaluate the prevalence of HCWs susceptible to measles, mumps, rubella and varicella infection. |

| Esposito et al.21 | Retrospective | 2006 | 2240 | A cross-sectional study of influenza vaccination coverage among HCWs as well as their knowledge of and attitudes toward influenza vaccination. |

| Alicino et al.22 | Prospective | 2005–2014 | 929 | A comprehensive, multifaceted intervention project based on education, promotion, and easy access to influenza vaccination. |

HCWs: Health Care Workers; HBV: hepatitis B virus;

Hospitals

HBV

A 2-year seroepidemiological study performed by Fortunato et al. in Puglia, a region of Southern Italy, reported that the overall vaccination rate versus HBV among HCWs was 70.1%; data stratified by hospital areas showed that rates among workers were 66.8% in medical departments, 70.1% in surgical departments, and 79.2% in intensive care units. HCWs employed in intensive care unit, with younger age and short-term length of service were more likely to be vaccinated (p < 0.05). Sixty percent of the professionals had received proper immunization recommendation: data showed that receiving the proposal by an Occupational Health Physician and a General Practitioner or from the Vaccination Service was associated with HBV vaccine uptake (p < 0.001).13

In the survey by Stroffolini et al., 1,632 HCWs were randomly selected within 15 Italian public hospitals, and a self-administered questionnaire was used in order to investigate HBV vaccination rates: a statistically significant difference emerged between Northern (93.1%) and Southern (77.7%) Italian regions. The overall immunization rate resulted 85.3%, and about 15% of the HCWs resulted susceptible to HBV infection. The logistic regression analysis demonstrated that residence in the Northern Italy (OR 4.2; 95% CI 2.6–6.7) and younger age (OR 4.5; 95% CI 2.6–7.8) were the only independent predictors of vaccine acceptance among HCWs.14

A risk assessment campaign among HCWs of a Local Health Authority in Sardinia region was conducted in order to identify proper and tailored interventions for the prevention of trasmissible infections (i.e., blood-borne pathogens) in the healthcare setting. In this research, HBV seroprevalence among HCWs resulted < 1%. Among blood-borne-seropositive HCWs, no specific clusters by job task and working area emerged in the investigation. HBV seroprotection resulted < 70%.15

The same Author performed another survey to investigate preventive policies and practices against Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, targeted for workers employed in hospitals of the Sardinia Region. A total of 32 Hospital Health Management out of all Sardinia Hospitals were enrolled in the study, and 30 (93.8%) joined the survey: data on immunization rates were available in 14 (46.7%) hospitals. The regional average HBV immunization rate resulted 76%; 5 hospitals reported values below the average (range: 63% – 67%) and 9 above it (range: 77% – 92%). HBV antibody testing was performed in all the hospitals included in the survey, but only 14 collected data using informatics systems.16

Measles and rubella

A seroprevalence study was performed between 2009 and 2010 by Campagna et al. in 9 hospital located in North and Central Italy, in order to evaluate the risk assessment, health surveillance and fitness for work of HCWs and to investigate susceptibility and vaccination rates vs. rubella, measles, varicella and mumps. Out of the 32,196 HCWs included in the study, 9,874 (30.7%) and 8,668 (27.0%) were tested for rubella and measles antibodies, respectively. The seroprevalence for rubella was 91.1%, ranging between 47 and 96.8% across the 9 hospitals. With respect to measles, the seroprevalence rate resulted 93%, ranging between 71.4 and 97.8%.17

Between 2007 and 2012, another seroepidemiological study was performed by Cologni et al. in Lombardia, a region in Northern Italy, to investigate the prevalence of HCWs susceptible to rubella, measles, varicella and mumps. Four thousand HCWs were recruited: protection resulted in 93.7% and 89.5% for rubella and measles, respectively.18

Fedeli et al. performed a retrospective cohort study to investigate the susceptibility to measles, mumps, rubella and varicella among HCWs. Three hundred and 3three subjects were tested, (203 nursing staff, 25 medical staff, 92 laboratory technicians and 13 administrative personnel): overall, 97.6% and 98.2% resulted seroprotected against rubella and measles, respectively.19

In the above mentioned study by Fortunato et al. vaccination rates and determinants of adherence to recommended immunizations among HCWs were investigated. The study was performed between 2009 and 2011 using an interview-based standardized anonymous questionnaire administered to hospital professionals. Out of the 2,198 HCWs returning the questionnaire, 954 (43.4%) and 1055 (48.0%) reported a history of rubella and mumps, respectively. Immunization rates for MMR vaccine resulted 9.7%. Susceptible nurses were more likely to be immunized than other professionals belonging to other categories (i.e., physicians, other HCWs). In the logistic regression analysis, MMR vaccination was independently associated with younger age (OR = 1.9; 95% CI = 1.2–3.0; p < 0.01) and with short length of service (OR = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.1–2.8; p < 0.05).13

Another seroepidemiological study was performed by Porru et al. in a public hospital in Lombardia, a Northern Italian Region, to evaluate the prevalence of HCWs susceptible to measles, mumps, rubella and varicella. Demographic, clinical and occupational information were collected during the study period: seroprevalence was 89% and 92% for rubella and measles, respectively. HCWs aged less than 36 y and residents were found more likely to be susceptible for these microbial agents. Seroprevalence resulted higher among HCWs employed in infectious disease and pediatric departments, while no significant difference emerged for other investigated variables, such as gender and being employed in the medical/surgical areas.20

As already reported, Campagna et al. investigated the risk of infections among HCWs of a Sardinian Local Health Authority. Nearly 50% of HCWs were tested for exanthematic diseases: the seroprevalence was 95% for measles (1,105 out of 1,163 subjects tested) and varicella (1,100 out of 1,159 subjects tested), 90% for rubella (1,115 out of 1,241 subjects tested) and 84% for mumps (996 out of 1,179 subjects tested).15

Influenza

In 2006, a cross-sectional study investigating vaccination rate among HCWs, as well as their knowledge and attitudes toward immunization, was performed in Lombardia, in Northern Italy. A total of 2,240 HCWs (1,110 physicians - 49.6%; 891 nurses - 39.8%; 239 paramedics - 10.7%) were enrolled in the study. Nine hundred and 10 (40.6%) HCWs were employed in medical department, 440 (19.6%) in surgical department, 346 (15.4%) in emergency department, and 544 (24.3%) in services department. Immunization rates among HCWs varied across the hospital areas, ranging between 17.6% and 24.3%, at the emergency and the surgical departments, respectively. The majority of HCWs received immunization within the Healthcare Surveillance Program of the hospital.21

In 2015, Alicino et al. conducted a comprehensive, multifaceted intervention project based on education, active promotion, and easy access to influenza vaccination at the referral adult acute-care teaching hospital of Liguria, a Northern Italian Region. Furthermore, since 2013/2014, a pilot project was implemented to improve immunization rates among HCWs employed in high-risk areas (i.e., hematological and oncological wards, intensive care units, emergency and geriatric wards). Since the beginning of the project, vaccination rates steadily increased from 20% in 2006/07 to 34% in 2009/10. In the season 2009/10 a peak of 34% was reached for seasonal influenza, but only 15% of HCWs resulted immunized for H1N1 pandemic strain. In the following seasons, immunization rates declined, ranging between 11% and 16%. With respect to the pilot project, 929 (27.0%) out of 3,444 HCWs employed in the hospital were included in the study, and 701 (75.5%) professionals signed an informed vaccination consent or dissent. Immunization rates HCWs included in the pilot project were higher compared with those of professionals not included in the study (21.1 vs 13.8%; p<0.0001). The main difference emerged among physicians (41.5% vs. 25.2%; p<0.0001), while no difference were registered in vaccination rates among nurses (13.1% vs. 10.6%; p<0.0001) and other clinical professionals (10.6% vs. 9.0%; p<0.0001).22 Results of an influenza vaccination campaign, conducted during the same season in another Italian region, by communication to units and nurses managers showed that vaccination rate was < 10%.15

In another survey by Campagna et al., 23 (76.7%) out of the 30 hospitals accomplished the vaccination campaign against flu, between October and December 2011. With respect to the communication methods for HCWs, 18 (78.3%) hospitals provided information by newsletter to unit managers, nursing and technicians coordinator, 8 (34.8%) sending newsletter to unit managers only, 7 (30.4%) through active call, and 2 (8.7%) using posters and advertising. Data of Vaccination coverage among HCWs were reported only by 23 hospitals. The Immunization rates reported in the survey resulted lower than 10% in most of the hospitals included, reaching highest values, between 21% and 25%, only in one hospital.16

Discussion

The results of this systematic review update the status of the art concerning susceptibility to VPDs and vaccination adherence among HCWs in Italy. Moreover, our study provides useful insights on this issue in an Obstetric Unit of an adult acute care University Hospital in North Western Italy, an occupational setting where HCWs are at risk of both acquire and spread relevant VPDs.

Our results show that further efforts are required both to improve the awareness among HCWs and to guarantee the early recognition and prompt immunization of susceptible professionals within the Healthcare Surveillance Programs in Italy.

Increasing awareness on the importance of vaccination among professionals employed in the healthcare services is one of the main goals of the European project HProImmune. It started in 2011 to promote immunization among HCWs, developing and improving communication tools and educational materials.23 Protection against VPDs needs appropriate resources for setting-up preventive measures and training tailored for HCWs: these investments can avoid the costs of non-protection in terms of worker's health and safety, productivity, and quality of work environment.24 Moreover, as these professionals have the potential of influencing patients' vaccination uptake, it is crucial to improve their confidence in vaccines, as well as immunization practices, and to engage them in specific activities targeting “vaccine hesitancy” among their patients and colleagues.3 In this view, novel strategies to address “vaccine hesitancy” (i.e., social mobilization, mass media, communication tool-based training for HCWs, non-financial incentives, and reminder/recall-based interventions) should be adopted to improve vaccination rates among HCWs. However, given the complexity of this phenomenon, and the limited evidence available on how it can be addressed, such strategies should be carefully tailored according to the target population, properly addressing the main reasons for hesitancy in the specific context.24

Several international healthcare organizations are evaluating the ethics of mandatory immunization policies, due to the insufficient vaccination coverage reported among HCWs:25 the rationale for this recommendation is that healthcare institutions have the duty to protect patients, to avoid nosocomial spread of infections and to keep working efficiently during outbreaks. Despite specific recommendations for HCWs immunization exists, considerable differences in terms of vaccination uptake have been reported between countries adopting mandatory policies and not: it is also true that strategies working in countries outside Europe may not work in our area and vice versa.11

The lack of knowledge by HCWs in this field is a critical issue: it seems to be due to the absence of information and educational campaigns. According to the findings of a recent systematic review on this topic, multicomponent and dialog-based interventions resulted as the most effective interventions.24 This is confirmed from the results of some recent investigations by our group, focused on influenza vaccination.22,26 Moreover, model legislation may be helpful to states wishing to implement immunization requirements in healthcare settings, although the uptake of model public health laws varies depending on subject matter. The overall quality of medical care could also benefit from this approach.27

Material and methods

Cross sectional study

Study period, materials and methods

The survey was performed at the Obstetric Unit of the University Hospital, IRCCS AOU San Martino-IST of Genoa, in Northern Italy, between the March 1st 2016 and August 31st 2016.

All subjects working at this Unit were proposed to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were: HCWs working at the Obstetric unit. Exclusion criteria were: medical, nurse and midwife students, failure to sign the informed consent foreseen in the Healthcare Surveillance Program at the IRCCS AOU San Martino – IST of Genoa.

Professional who entered the survey were interviewed about previous history of VPDs and current vaccination status: a structured questionnaire was administered by a trained physician, who adequately informed about the aims of the study, to collect data. In particular, professionals were asked about socio-demographic information, history of disease and vaccination status for rubella, measles, varicella, HBV, and influenza. All the professionals who were found to be susceptible for any VPDs received appropriate counselling and proper vaccination program was recommended.

All the activities have been performed according to the procedures of the Healthcare Surveillance Program at the IRCCS AOU San Martino - IST. Demographic, professional and clinical data were completely anonymised and analyzed according to privacy legislation.28

Systematic review

Protocol, eligibility criteria, information sources and search

This review was performed according to a-priori designed protocol and recommended for systematic reviews. PubMed/Medline, and Scopus were searched electronically between May and September 2016, utilizing combinations of the relevant medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, keywords, and word variants, alone or in combination: “HBV,” “measles,” “rubella,” “varicella,” “influenza,” “seroprevalence,” “susceptibility,” “vaccination coverage,” “heath care workers.” The search and selection criteria were restricted to English and Italian languages. Reference lists of relevant articles and reviews were hand searched for additional reports.

Study selection, data collection and data items

The inclusion criteria were original studies, conducted in Italy, that reported data on the seroprevalence/vaccination coverage of anti-HBV antibodies and/or anti-measles and/or anti-rubella antibodies and/or varicella antibodies and/or influenza in HCWs. Conference abstracts and proceedings were not included due to concerns regarding the inability to determine the quality of the methods. The PRISMA statement was used for reporting the Methods, Results and Discussion sections of the current review.29 The STROBE statement was used to assess the quality of the included studies (Table 4).30 No attempt was made to contact the authors and retrieve additional information. The included studies were sub-grouped in different categories according to the type of viral infection.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review based on the STROBE statement.

| Author | Study design | Clear definition of the study population | Clear description of assessment of the main outcome | Clear description of assessment of all outcomes | Description of missing data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fedeli U et al.19 | Retrospective | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Campagna M et al.17 | Retrospective | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Cologni L et al.18 | Retrospective | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Fortunato F et al.13 | Retrospective | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Porru S et al.20 | Retrospective | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Stroffolini T et al.14 | Retrospective | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Esposito S et al.21 | Retrospective | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Alicino C et al.22 | Prospective | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Copello F et al.15 | Prospective | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Campagna M et al.16 | Prospective | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Two authors (CS, ULRM) reviewed all the abstracts independently. Agreement about potential relevance was reached by consensus, and full text copies of those papers were obtained. Two reviewers (CS, ULRM) independently extracted relevant data regarding study characteristics and outcomes. Inconsistencies were discussed by the reviewers and consensus reached. Only studies published between 2000 and 2016 were included in the systematic review. Case reports, case series of less than 10 cases, reviews with no original data and duplicate publications were excluded.

Abbreviations

- dTap

Diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis

- ECDC

European Center for Disease Prevention and Control

- HCWs

Healthcare Workers

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- PNPV

Italian National Vaccination Plan

- MMR

Measles; Mumps; Rubella

- VPDs

Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

- WHO

World Health Organization

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- [1].World Health Organization (WHO) Occupational health Health workers. Health worker occupational health. Available at: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/hcworkers/en/. Accessed 14thMay2014. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Campins Martí M, Uriona Tuma S. General epi- demiology of infections acquired by health-care workers: immunization of health-care workers. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2014; 32:259-65; PMID:24656968; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.eimc.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Karafillakis E, Dinca I, Apfel F, Cecconi S, Wurz A, Takacs J, Suk J, Celentano LP, Kramarz P, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy among 395 healthcare workers in Europe: A qualitative study. Vaccine 2016; 34:5013-20; PMID: 27576074; 26942390http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. Italy 2016 Decreto Legislativo 9 aprile 2008 n. 81 - Testo Unico in materia di salute e sicurezza sul lavoro, 2016 update. Available at: http://www.lavoro.gov.it/priorita/Pagine/Testo-Unico-sulla-salute-e-sicurezza-sul-lavoro.aspx. Accessed 18thSeptember2016.

- [5].Ministero della Salute. Italy (2012) Piano della Prevenzione Vaccinale 2012-2014. Intesa Stato- Regioni del 22 febbraio 2012. G.U. Serie Generale, n. 60 del 12 marzo 2012. Italian. Available at: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1721_allegato.pdf. Accessed 20thMay2014.

- [6].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Gynecological Practice . Committee opinion No. 655: Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus infections in obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2016; 127:e70-4; PMID:26942390; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ. What obstetric health care providers need to know about measles and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 126:163-70; PMID:25899422; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].McCubbin JH, Smith JS. Rubella in a practicing obstetrician: a preventable problem. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1980; 136:1087; PMID:7369267; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0002-9378(80)90655-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tsagris V, Nika A, Kyriakou D, Kapetanakis I, Harahousou E, Stripeli F, Maltezou H, Tsolia M. Influenza A/H1N1/2009 outbreak in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect 2012; 81:36-40; PMID:22463979; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Swamy GK, Heine RP. Vaccinations for pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 125:212-26; PMID:25560127; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Galanakis E, Jansen A, Lopalco PL, Giesecke J. Ethics of mandatory vaccination for healthcare workers. Euro Surveill 2013; 18:20627; PMID:24229791; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.45.20627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Prato R, Tafuri S, Fortunato F, Martinelli D. Vaccination in healthcare workers: an Italian perspective. Expert Rev Vaccines 2010; 9:277-83; PMID:20218856; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1586/erv.10.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fortunato F, Tafuri S, Cozza V, Martinelli D, Prato R. Low vaccination coverage among italian healthcare workers in 2013. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015; 11:133-9; PMID:25483526; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/hv.34415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stroffolini T, Coppola R, Carvelli C, D'Angelo T, De Masi S, Maffei C, Marzolini F, Ragni P, Cotichini R, Zotti C, et al.. Increasing hepatitis B vaccination coverage among healthcare workers in Italy 10 years apart. Dig Liver Dis 2008; 40:275-7; PMID:18083081; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.dld.2007.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Copello F, Garbarino S, Messineo A, Campagna M, Durando P. Collaborators. occupational medicine and hygiene: applied research in Italy. J Prev Med Hyg 2015; 56:E102-10; PMID:26789987 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Campagna M, Argiolas F, Soggiu B, Mereu NM, Lai A, Galletta M, Coppola RC. Current preventive policies and practices against Vaccine-Preventable Diseases and tuberculosis targeted for workers from hospitals of the Sardinia Region, Italy. J Prev Med Hyg 2016; 57:E69-74; PMID:27582631 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Campagna M, Bacis M, Belotti L, Biggi N, Carrer P, Cologni L, Gattinis V, Lodi V, Magnavita N, Micheloni G, et al.. Exanthemic diseases (measles, chickenpox, rubella and parotitis). Focus on screening and health surveillance of health workers: results and perspectives of a multicenter working group. G Ital Med Lav Ergon 2010; 32:298-303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cologni L, Belotti L, Bacis M, Moioli F, Goglio A, Mosconi G. Measles, mumps, rubella and varicella: antibody titration and vaccinations in a large hospital. G Ital Med Lav Ergon 2012; 34:272-4; PMID:23405639 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fedeli U, Zanetti C, Saia B. Susceptibility of healthcare workers to measles, mumps, rubella and varicella. J Hosp Infect 2002; 51:133-135; PMID:12090801; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1053/jhin.2002.1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Porru S, Campagna M, Arici C, Carta A, Placidi D, Crotti A, Parrinello G, Alessio L. Susceptibility to varicella-zoster, measles, rosacea and mumps among health care workers in a Northern Italy hospital. G Ital Med Lav Ergon 2007; 29:407-9; PMID:18409748 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Esposito S, Bosis S, Pelucchi C, Tremolati E, Sabatini C, Semino M, Marchisio P, Della Croce F, Principi N. Influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in a multidisciplinary University hospital in Italy. BMC Public Health 2008; 8:422; PMID:19105838; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2458-8-422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Alicino C, Iudici R, Barberis I, Paganino C, Cacciani R, Zacconi M, Battistini A, Bellina D, Di Bella AM, Talamini A, et al.. Influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in Italy. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015; 11:95-100; PMID:25483521; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/hv.34362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].HProImmune Promotion of immunization for health professionals in Europe. Available at: http://www.hproimmune.eu/. Accessed 30thMay2014.

- [24].Jarrett C, Wilson R, O'Leary M, Eckersberger E, Larson HJ. SAGE Working Group on vaccine hesitancy. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy - A systematic review. Vaccine 2015; 33:4180-90; PMID:25896377; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Maltezou HC, Wicker S, Borg M, Heininger U, Puro V, Theodoridou M, Poland GA. Vaccination policies for health-care workers in acute healthcare facilities in Europe. Vaccine 2011; 29:9557-62; PMID:21964058; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Durando P, Alicino C, Dini G, Barberis I, Bagnasco AM, Iudici R, Zanini M, Martini M, Toletone A, Paganino C, et al.. Determinants ofadherence to seasonal influenza vaccination among healthcare workers from anItalian region: results from a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016; 6(5):e010779; PMID:27188810; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lindley MC, Horlick GA, Shefer AM, Shaw FE, Gorji M. Assessing state immunization requirements for healthcare workers and patients. Am J Prev Med 2007; 32:459-465; PMID:17533060; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Italian Law decree n.196, 30 June 2003 (article 24) http://www.camera.it/parlam/leggi/deleghe/03196dl.htm. Accessed 4thDecember2015.

- [29].Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6:e1000097; PMID:19621072; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61:344-9; PMID:18313558; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]