Abstract

Cortical interneurons (cINs) are a diverse group of locally projecting neurons essential to the organization and regulation of neural networks. Though they comprise only ~20% of neurons in the neocortex, their dynamic modulation of cortical activity is requisite for normal cognition and underlies multiple aspects of learning and memory. While displaying significant morphological, molecular, and electrophysiological variability, cINs collectively function to maintain the excitatory-inhibitory balance in the cortex by dampening hyperexcitability and synchronizing activity of projection neurons, primarily through use of the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Disruption of the excitatory-inhibitory balance is a common pathophysiological feature of multiple seizure and neuropsychiatric disorders, including epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism. While most studies have focused on genetic disruption of cIN development in these conditions, emerging evidence indicates that cIN development is exquisitely sensitive to teratogenic disruption. Here, we review key aspects of cIN development, including specification, migration, and integration into neural circuits. Additionally, we examine the mechanisms by which prenatal exposure to common chemical and environmental agents disrupt these events in preclinical models. Understanding how genetic and environmental factors interact to disrupt cIN development and function has tremendous potential to advance prevention and treatment of prevalent seizure and neuropsychiatric illnesses.

Keywords: cortical development, interneuron, developmental neurotoxicity, gene-environment, schizophrenia, seizure

1. Introduction

Disrupted neocortical physiology underlies the neurobehavioral and/or psychiatric pathology associated with a number of common disorders such as epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism. Though immensely complex, the neocortex is canonically organized along two primary axes: the horizontal laminae and the radial microcircuit columns. Microcircuits, the basic elements of sensory perception and cognition, are composed of functionally entwined excitatory pyramidal neurons and inhibitory interneurons. Pyramidal cells project their axons to distant regions of the cortex or to other parts of the brain and predominantly transmit signals using the neurotransmitter glutamate. Cortical interneurons (cINs), on the other hand, have short, locally connected axons and aspiny to sparsely spiny dendrites. These cells are primarily GABAergic and provide inhibitory input that modulates signal transmission of pyramidal cells1,2. Dysfunction of cINs, which are largely responsible for regulating cortical excitability and synchronizing oscillatory activity, is strongly linked to the development of cognitive and behavioral deficits3–6.

Abnormalities in the neocortical excitatory-inhibitory balance, resulting from cIN defects, are extensively implicated in the pathophysiology of both seizure disorders and neuropsychiatric illnesses7–14 (reviewed by Marín et al. and Inan et al.15,16). Increasing evidence supports the idea that cIN abnormalities underlie impairment of complex cognitive tasks, including working memory, sensory integration, and language skills. Though interactions between genetic and environmental influences are suspected to be etiologically culpable in the majority of cases of epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism, previous examinations have focused primarily on the potential impact of these factors during the postnatal period17. However, several genetic mutations associated with these diseases disrupt the function of genes involved in cIN development18–20. Additionally, recent studies demonstrate that in utero exposure to a number of teratogens, such as alcohol, cigarette smoke, and cannabinoids, disrupts cIN development and results in behavioral abnormalities in animal models21–27. Intriguingly, there is also a growing body of epidemiological data linking human prenatal exposure to these factors to the development of seizure and neuropsychiatric illnesses later in life28–30.

This review examines recent data from preclinical studies that support the emerging link between exposure to common chemical and environmental compounds during critical periods of neurodevelopment and cIN abnormalities associated with complex neuropsychiatric conditions. Though current understanding of cIN development remains incomplete, it is posited that genetic programs controlling cell fate are specified during early embryogenesis and modified by local signals during the post-mitotic maturation period when cINs are migrating and integrating into the cortical circuitry31,32. Elucidating gene-environment interactions that disrupt these complex events should be a priority for developmental neuroscientists as solving this intricate etiological puzzle could usher in the development of evidence-based prevention strategies and treatments for myriad diseases.

2. Classification of Cortical Interneurons

Consistency in classification is vital for understanding how cINs behave within the neural circuitry and elucidating how their dysfunction may contribute to pathological states. Despite a concerted effort over the past two decades, advancement of a single unifying system has been stymied by the innate heterogeneity and often-overlapping phenotypic range of these cells33,34. The Petilla terminology, proposed by a distinguished group of scholars following an international summit in 2005, improved uniformity of nomenclature used to describe cIN subtypes, but clear groupings remain elusive and classification continues to be primarily descriptive35.

Extrapolating from what is known about interneuronal specification in the spinal cord36, it was initially hypothesized that understanding the developmental origins of cINs would hold the key to defining cardinal classes37–39. Accordingly, a primary focus of the field has been exploring how early specification events drive cIN diversity. While several distinct progenitor niches specified through unique transcriptional cascades have been identified, they do not completely account for the observed biological complexity31,40–47. Additionally, groups of similar cINs within the neocortex and hippocampus have disparate lineages, indicating that different progenitor niches may produce the same subtypes48. These observations potentially stem from the presence of highly intricate genetic programs that precisely control cell fate or the remarkable ability of progenitors to respond adaptively to extrinsic influences.

Though no comprehensive classification system yet exists, it is still useful to broadly categorize cINs in terms of neurochemical composition, morphology, and connectivity. Since nearly all cINs express either the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin (PV), the neuropeptide somatostatin (SST), or the ionotropic serotonin receptor 5HT3aR, these markers are frequently used to delineate cINs (listed in Table 1)2,49,50. The PV-expressing cells make up the largest group, accounting for roughly 40% of all cINs. Cells in this group are typically fast spiking and are often divided into two primary populations based on morphology: large basket cells and chandelier cells. Large basket cells tend to synapse at the soma or proximal dendrite of target cells located across multiple layers and are thought to be the dominant source of cortical inhibition51,52. Cells of the SST-expressing group account for about 30% of cINs, are mostly intrinsic burst spiking or accommodating, often target distal dendrites, and can be subdivided into two main groups: Martinotti and small basket cells3. Lastly, the 5HT3aR-expressing group accounts for about 30% of cINs and includes the small bipolar cells that express vasointestinal peptide (VIP) as well as the neurogliaform cells that do not express VIP53,54. Neurogliaform cells are fast-adapting and appear to have a unique place in neural circuits as the only cINs that primarily target other local circuit neurons55.

Table 1. Classification of Cortical Interneurons.

Cortical interneurons (cINs) are grouped into primary classes based on presence of three markers that are expressed by nearly 100% of cINs: parvalbumin (PV), somatostatin (SST), and the 5HT3aR serotonin receptor. The vast majority of cINs are born within the medial and caudal ganglionic eminences (MGE and CGE, respectively). Cell fate is determined, at least in part, through the combinatorial expression of region-specific transcription factors. Subclasses are highly diverse in terms of morphology, biochemical composition, and electrophysiological profile.

| Marker | Fate Specification | Birthplace | % of Total | Subclasses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | Dlx1/2, Nkx2.1, Lhx6, Sox6, Sip1 | MGE | ~40% | Large basket, Chandelier |

| SST | Dlx1/2, Nkx2.1, Lhx6, Sox6, Sip1, SatB1 | MGE | ~30% | Martinotti, Small basket |

| 5HT3aR | Dlx1/2, Prox1, CoupTF2 | CGE | ~30% | Neurogliaform, Small Bipolar |

3. Developmental Origins of Cortical Interneurons

Formative work performed by Anderson et al. in 1997 demonstrated that, in contrast to pyramidal neurons which are produced in the dorsal telencephalon, cINs are born within the subpallium and must migrate tangentially to the cortex subsequent to cell cycle exit (schematic in Figure 1 shows migratory routes)56. The embryonic subpallium can be divided into five distinct anatomical regions: the medial, lateral, and caudal ganglionic eminences (MGE, LGE, and CGE, respectively), the preoptic area (POA), and the septal anlage. The ganglionic eminences are transient developmental structures that arise from neuroepithelial swellings in the ventral telencephalon around embryonic day 10.5 in the mouse. It was originally suggested that cINs are born within the LGE56, but further investigation revealed that the majority actually originate within the MGE and CGE40,46,57, with minority contributions from the LGE and POA58,59. Fate mapping and lineage tracing experiments additionally established that ~60% of cINs, including both PV- and SST-expressing subtypes, are generated within the MGE41,57,60 while the 5HT3aR-expressing cells are generated in the CGE53. Generation of cINs occurs primarily between embryonic days 11 and 17 in the mouse, which roughly corresponds to weeks 5 to 15 of pregnancy in humans61. Although there is some evidence that the generation of cINs in humans does not occur exclusively in the subpallium as it does in rodents62, examination of human fetal tissue indicates that the ganglionic eminences are still the primary source of cINs63.

Figure 1. Cortical Interneuron Development.

Upper left: Three-dimensional reconstruction of the brain and face of a fetal mouse derived from high resolution magnetic resonance microscopy sections. The light green square indicates plane of section for the schematic illustration to the right. Right: Schematic illustration of the developing telencephalon at approximately embryonic day 15. Dark green arrows indicate possible routes of cortical interneuron (cIN) tangential migration from the subpallial proliferative zones to the cortex. cINs born during the early neurogenic period primarily enter the cortex via a superficial stream within the marginal zone (1,3), while those that are born during the late neurogenic period enter via a deeper stream into the intermediate and subventricular zones (2). Subsequent to tangential migration, cINs align along either side of the cortical plate before undergoing radial migration and integration.

LGE, MGE, CGE: lateral, medial, and caudal ganglionic eminences. POA: preoptic area.

3.1 Fate Determination

Transcriptional networks play an important role in early cIN fate specification (Table 1). The co-repressive morphogens FGF8 and Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) first establish dorsal and ventral domains, respectively, within the forebrain prior to the appearance of the ganglionic eminences. Expression of distal-less homeobox (Dlx) transcription factor genes then imparts regional identity to subpallial neural progenitor cells20,64,65. Expression of these genes, especially the functionally redundant members Dlx1 and Dlx2, remains important through later stages of development and is required for tangential migration as well as various aspects of post-mitotic differentiation and maturation, including dendritic arborization66–68. Nkx2.1, a homeobox transcription factor-encoding gene, is expressed during early stages of neuroepithelial patterning and is a key regulator of cIN fate. Its expression, which is induced and maintained in the MGE by SHH, is required for the initiation of transcriptional cascades culminating in the specification of both PV- and SST-expressing subtypes44,69,70. Knockout of either Shh or Nkx2.1 in the mouse results in a profound loss of MGE-derived cINs71,72. Lhx6, a lim homeodomain transcription factor-encoding gene, is a direct target of NKX2.1 and is necessary for the correct migration and laminar distribution of MGE-derived cINs73,74. Interestingly, reduced Lhx6 mRNA levels have been reported in patients with schizophrenia75. Sox6 and Sip1 appear to be important downstream effectors in both cascades as well34. SatB1 is additionally required for post-mitotic maturation and survival of SST-expressing cells76. Though less is known about the transcriptional specification of 5HT3aR-expressing cINs, a recent study demonstrated that expression of Prox1 and CoupTF2 within the CGE is necessary54. Finally, expression of Dbx1 in the POA appears to be required for the specification of the small but highly diverse group of cINs generated in this region77.

Within the MGE, a number of key spatiotemporal regulators of cIN fate have been identified. The gradient of SHH expression influences the fate of MGE-derived cINs: progenitors exposed to high levels mainly differentiate into SST-expressing cells while those exposed to lower levels mainly differentiate into PV-expressing cells78. Additionally, a dorsoventral bias was revealed by explant experiments that demonstrated dorsal MGE tissue predominantly gives rise to SST-expressing cells while ventral MGE tissue predominantly gives rise to PV-expressing cells45,47. A recent study also showed that SST-expressing cINs are preferentially derived from apical progenitors within the ventricular zone of the MGE while PV-expressing cINs are preferentially derived from basal progenitors within the subventricular zone of the MGE79. Lastly, evidence from birthdating analyses suggests that there is a bias for production of SST-expressing cINs during the early neurogenic period and PV-expressing cINs during the late neurogenic period43. Currently, though, the potential impact of environmental disruption on these early specification events is poorly understood.

3.2 Migration and Integration

Following cell cycle exit, cIN precursors migrate tangentially to the dorsal telencephalon and align along both sides of the developing cortical plate before undergoing radial migration and integration into neural circuits. Analogous to the radial migration of pyramidal cells, this requires permissive substrates, modulation of cell adhesion molecules, and intricate combinations of chemoattractive and chemorepulsive factors80. Both Slit-Robo and Eph-Ephrin signaling have been implicated in the initial guidance of cINs away from the subpallial proliferative zones81,82. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and neurotrophin 4 (NT4) function as key motogens which drive migrating cINs toward the pallium83–86. Once cINs have reached the developing cortical plate, neuregulin1-ErbB4 and stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1)-Cxrc4 signaling appear to play an important role in regulating cIN integration87,88. Lastly, upregulation of the potassium-chloride co-transporter KCC2 mediates the excitatory to inhibitory change in GABAergic signaling89. This switch, which begins late in gestation and continues into the postnatal period, is sufficient to suppress cIN motility and marks the initiation of terminal differentiation and circuit refinement, a stage during which cINs adopt mature expression profiles and connective characteristics.

To better understand the function of cINs within neural networks and how their dysfunction may contribute to disease, an increasing effort has been made in recent years to understand how cINs are integrated into the neocortical circuitry. Similar to pyramidal neurons, the laminar fate of MGE-derived cINs correlates strongly with birthdate40,41. Generation of these neurons occurs in an “inside-out” fashion with earlier born cells occupying the deep cortical layers and later born cells filling in the more superficial layers. In contrast, the ultimate location of CGE-derived cINs appears to be more heavily dependent on radial sorting mechanisms90–92. Despite the fact that these cells initiate migration and entry into the cortical plate concurrently to age-matched MGE-derived cINs, their final destination cannot be predicted by birthdate.

Recent advances in clonal labeling techniques have allowed for more sophisticated analyses of the distribution of cIN lineages through the cortex. Though this process appears to be stochastic, evidence suggests that cells sharing a common lineage are targeted to specific cortical areas93. Additionally, individual neuronal precursor cells have the capacity to give rise to phenotypically divergent mature cINs94. Thus, functional interactions with local excitatory neurons are thought to play an important role in the final postmigratory differentiation of cINs34,95. Furthermore, cINs exhibit remarkable functional plasticity and molecular expressivity in response to external stimuli96. Together these findings indicate that cIN fate is far more flexible than originally suspected and is not exclusively predetermined by developmental origin but rather can be modified by the local milieu or extrinsic environmental factors during the postmitotic period.

4. Disruption of Cortical Interneuron Development

Defects in early cIN development can have a variety of significant anatomical and physiological effects. Genetic mutations and/or exposure to teratogens during critical periods of brain development have the capacity to alter the total number of cINs produced, disrupt tangential migration patterns, and/or cause subtype misspecification errors with a variety of functional manifestations. Consequences can range from severe, debilitating neurological disability to subtler impairments in learning and social behavior. Critically, abnormal cIN development is implicated in the pathogenesis of a number of common seizure and neuropsychiatric disorders, including epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism. However, the intrinsic and extrinsic factors capable of disrupting cIN development, and the potential synergistic interactions between these factors, are not yet completely understood.

Despite extensive efforts to elucidate the genetic basis of diseases such as epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism, a limited number of definitive associations have been uncovered. Though large genome-wide association studies have been undertaken, no single mutation has been identified that adequately predicts risk of the above diseases in large populations (for further discussion of the genetic basis of these diseases see Myers et al., Farrell et al., and Muhle et al.97–99). Of the genetic variants implicated in these disorders, the vast majority appear to act with low penetrance and broad phenotypic expressivity, features indicative of significant etiological complexity. For example, 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (OMIM #188400), which results in an abnormal distribution of PV-expressing cINs, has been identified as the cause of schizophrenia in ~1% of cases100,101. However, only about 25% of mutation carriers meet the criteria for diagnosis of schizophrenia102. Further, examination of twin concordance for epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism indicate that, as with other complex diseases, it is highly likely that the etiology of these disorders is multifactorial103–108. Exemplifying this concept, abnormal cIN development and schizophrenia-like behavioral pathology in dominant-negative DISC1 mice is exacerbated by neonatal immune activation109. This finding highlights the need for careful exploration of how relevant environmental agents augment risk of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. As such, there has recently been an increased effort to understand how naturally occurring compounds, environmentally significant chemical hazards, and illicit/pharmaceutical drugs impact cIN development. Within the past 5 years, more than a dozen reports have been published that directly and mechanistically link these factors to perturbation of key cIN developmental events in animal models (see Figure 2). Here, we focus our discussion on the molecular outcomes associated with prenatal exposure to four common human teratogens: ethanol, cigarette smoke, and illicit and prescription drugs.

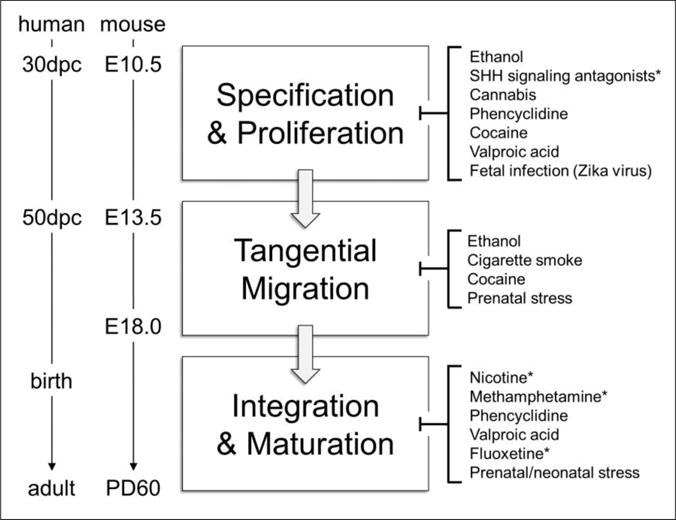

Figure 2. Cortical Interneuron Development is Highly Sensitive to Teratogenic Disruption.

Left: Timeline of critical periods in human and mouse cortical interneuron (cIN) ontogenesis. Right: Common teratogens target key events in cIN development including initial fate specification, proliferation, tangential migration from the subpallium to the cortex, circuit integration, and adoption of mature expression and connective profiles. Highlighting the emergent nature of the field, 68% (n=15/22) of the studies supporting this list were published within the past 5 years. Asterisks (*) denote areas where further experimental evidence is required to substantiate the association.

dpc: days post conception, E: embryonic day, PD: postnatal day.

4.1 Cortical Interneurons as a Teratogenic Target

4.1.1 Prenatal Ethanol Exposure

Though the devastating effects of maternal alcohol consumption on the developing fetus were first documented over a century ago, it is estimated that roughly 1 in 10 pregnant women in the US still uses alcohol during pregnancy110,111. Prenatal ethanol exposure causes a range of structural and functional abnormalities, collectively termed fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). At the severe end of this spectrum is fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), marked by growth retardation, a specific pattern of craniofacial dysmorphology, and CNS dysfunction (relevant neurobehavioral and clinical aspects of FASD/FAS have been recently reviewed by Coriale et al.112). Multiple characteristics of FAS and FASD in patient cohorts are consistent with a cIN-mediated excitatory-inhibitory imbalance including heightened risk of seizures and epilepsy, and impaired executive functioning113. In mice, prenatal alcohol exposures that cause the classic facial features of full-blown FAS also result in a marked deficiency of the MGE, a reduced number of cIN precursors, and abnormal cIN tangential migration patterns114–116. Such exposures significantly reduce the total number of cINs and alter the subtype balance in the postnatal brain27. In addition, early binge-type prenatal exposure has been linked to an abnormal distribution of PV-expressing cINs in the medial prefrontal cortex117. This interneuropathy persists into adulthood and is marked by significant electrophysiological and behavioral alterations in affected mice118.

The type and severity of CNS abnormalities resulting from prenatal ethanol exposure, however, appear to depend upon variables beyond the level of exposure itself119,120. Animal models show that the impact of alcohol exposure on the developing embryo is shaped by both the timing of exposure as well as interacting genetic variations121–124. These studies also highlight the interaction of ethanol with SHH signaling by demonstrating that mutations in multiple pathway members increase the severity of ethanol-induced abnormalities. In fact, ethanol appears to act, at least in part, by directly antagonizing the SHH signaling pathway125–127. Although multiple mechanisms of action have been proposed, ethanol-mediated disruption of SHH signal transduction serves as a unifying basis for the classic features of FAS and FASD, including facial dysmorphology, and cIN abnormalities. Interestingly, this pathway is also inhibited by a number of dietary and environmental chemicals, including compounds found in tomatoes, potatoes, and insecticide formulations128,129. The relationship between prenatal exposure to these compounds and cIN pathology, however, has not yet been investigated.

4.1.2 Cigarette Smoking

Though maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy has been slowly declining over the past few decades, self-reporting indicates that more than 10% of women in the US continue to smoke through the gestational period130. Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy is associated with numerous poor outcomes including fetal growth restriction, spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, and increased risk of sudden infant death29. Additionally, epidemiological studies strongly link maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy to the diagnosis of psychobehavioral pathology during childhood and adolescence28,131–135. These studies show that children born to mothers that smoke during pregnancy are at increased risk of developing neuropsychiatric conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder. Though the biological basis of this is not yet fully understood, prenatal nicotine exposure may have a direct effect on cINs in developing neural networks. Activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on human cINs can trigger post-synaptic release of GABA136. Though it is plausible that inappropriate activation of developing cINs may disrupt circuit dynamics and impair formation of networks, there is currently insufficient evidence to support this conclusion.

Intriguingly, an alternative explanation for the link between maternal smoking and the development of psychobehavioral disorders has recently been advanced. In the mouse, prenatal exposure to carbon monoxide, which models aspects of the effects of maternal cigarette smoking, downregulates signaling through cGMP and its target vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein, leading to disrupted actin polymerization in developing neurons, reduced migratory capacity, and abnormal laminar distribution of cINs, but not excitatory neurons, in the adult brain23. Furthermore, these effects were correlated with the development of abnormal sensory-related behaviors in mice.

Since cigarette smoke is a cocktail composed of thousands of chemicals, maternal smoking may alter numerous aspects of cIN development. As this is explored in greater depth, it is likely that additional mechanistic explanations for the link between smoking during pregnancy and the development of complex neuropsychiatric disorders will begin to emerge. Moving forward, it will be important to remain cognizant of the potential for gene-environment interactions and to examine how individual genetic susceptibility may influence the degree to which these cIN disruptions affect neurobehavioral function.

4.1.3 Illicit and Prescription Drug Use

Associating illicit and prescription drug use during pregnancy with specific teratogenic outcomes is difficult as multiple substances may be used together and self-reporting is often inaccurate. Additionally, a single substance may have variable effects depending on dose and timing of exposure while different substances can have similar, overlapping effects. A 2012 survey indicated that about 5% of pregnant women had used an illicit substance within the past month137. A conservative extrapolation suggests more than 200,000 babies in the US are exposed to illicit drugs in utero each year. This staggering statistic speaks the importance of understanding both the structural and functional effects such substances may have on developing neural systems.

Though women of childbearing age may attempt to reduce substance use during pregnancy, confirmation of pregnancy often comes after critical windows of neurodevelopment have passed. Cannabis (marijuana) is one of the most widely used illicit substances and prenatal exposure is linked to a number of poor neurobehavioral outcomes138. Endogenous cannabinoid signaling is thought to play a role in prenatal neurodevelopment and cannabinoid receptors are expressed in the cranial neural plate and prosencephalic neuroepithelium during periods of early forebrain patterning139. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive component of cannabis, effectively crosses the placenta and in utero exposure reduces the number of hippocampal interneurons produced and alters social behavior in mice25. Though the effects of THC on cIN development specifically are not known, prenatal exposure to synthetic cannabinoids during the period of neurulation profoundly disrupts cortical development in mice. Observed defects following treatment with the synthetic cannabinoid CP-55,940 range from cortical dysplasia to holoprosencephaly (incomplete medial forebrain division). Holoprosencephaly is marked by a deficiency of ventral midline tissue and co-occurs with a significant loss of SST-expressing cINs in humans140. This suggests that prenatal cannabis exposure, especially during the first trimester of pregnancy, has the potential to significantly perturb cIN development.

While less is known about how other drugs may impact developing cINs, there is sufficient evidence suggesting this is an area that deserves greater attention. Methamphetamine, a potent neurotoxin, selectively causes apoptosis of PV-positive, but not SST-positive, striatal interneurons141. Its effects on cINs and developing neuronal populations, though, have not yet been examined. Prenatal phencyclidine (PCP) exposure reduces the density of PV-expressing cINs and disrupts the formation of prefrontal cortical circuits leading to behavioral deficits in mice142. Intriguingly, prenatal cocaine exposure, which is thought to primarily target dopaminergic and serotonergic systems, impairs tangential migration and causes a reduction of both the total number of cINs and the percentage of PV-expressing cINs in the medial prefrontal cortex of adult mice143,144. The epidemiological significance of in utero methamphetamine, PCP, and cocaine exposures, however, is unknown.

Prescription drugs may also disrupt cIN development. Maternal use of valproic acid (VPA), a prescription anticonvulsant and mood stabilizer, during pregnancy has been strongly correlated with an increased risk of autism in the child145,146. Not surprisingly, exposure around the third week of pregnancy, the onset of neurulation, is reported to have the most devastating effects. In a rat model, prenatal VPA exposure results in hyperconnectivity of cortical microcircuits and a subsequent loss of signal integration, suggesting that function of cINs may be impaired147. Though the cellular and molecular effects of antidepressants are not yet completely understood, emerging evidence suggests that developing cINs may be susceptible to modulation by these drugs. Chronic administration of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine leads to structural changes in cINs and a reduction of PV-expressing cINs in the medial prefrontal cortex of adult mice148,149. The effects of fluoxetine on developing cINs, however, have not been examined despite evidence that the drug effectively crosses the placenta and leads to the development of anxiety-like behavior in prenatally exposed rats150,151. Clearly, further investigation into the effects of illicit and prescription drugs on the development of cINs is needed for accurate risk assessment and hazard communication.

4.1.4 Non-Chemical Factors

In addition to chemical insults, other extrinsic factors can alter cIN development. Complications during pregnancy are a known risk factor for the development of schizophrenia152. Though this link was previously thought to be a result of fetal hypoxia, recent studies demonstrated that in the mouse, prenatal stress impairs cIN migration, increases the total number of cINs present during critical periods of adolescence, delays maturation of PV-expressing cells, and alters social behavior24,153. Intriguingly, prenatal stress also leads to epigenetic modification of cINs and the development of schizophrenia-like behavioral features in mice154. In neonatal rats, exposure to bouts of intermittent hypoxia, which models hypoxia-related obstetric complications or severe respiratory disease, decreases PV-expressing cINs in the prefrontal cortex and increases anxiety-like behavior later in life155. A similar deficit of PV-expressing cINs was found in a model of maternal immune activation during pregnancy26, an established risk factor for the development of schizophrenia and autism in patient cohorts156–158. Lastly, fetal infections, which potentially lead to a loss of cIN progenitors, have also been linked to the development of schizophrenia later in life159. Notably, prenatal Zika virus infection was recently correlated with increased apoptosis of cIN progenitors160. How any of these factors potentially augment genetic predisposition, though, remains to be elucidated.

5. Future Directions

Previous efforts have focused heavily on understanding the genetics of common seizure and neuropsychiatric illnesses. However, it is quickly becoming evident that genetics alone cannot explain occurrence of these common conditions and detection of environmental factors that lead to cIN dysfunction is of utmost importance. The above examples constitute an important proof of principle that cIN development is exquisitely sensitive to teratogenic disruption, but the list is far from comprehensive. It is impractical to depend solely on epidemiological investigations and animal trials to uncover other operational environmental factors. Additionally, reliance on these methods limits ability to concurrently test interacting genetic susceptibilities. Thus, new approaches to screen for environmental factors that disrupt cIN development and to model gene-environment interactions must be developed.

Though etiological and biological complexity has long frustrated advancement of such tools, the technology and resources to do this are now becoming available to researchers161–163. Breakthroughs in cIN culture techniques, such as the ability to produce differentiated cINs from human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells, should spur development of in vitro testing models that not only replicate key biological complexities but are also genetically tractable and amenable to high throughput chemical screening164,165. As part of a concerted toxicology forecasting effort (ToxCast), the EPA assembled a small molecule library of over 1,800 chemicals with a broad range of structures from diverse sources including industrial and consumer products, food additives, and potentially “green” chemicals that could be safer alternatives to existing chemicals. Using this library to screen cultured cINs for defects in proliferation, differentiation, migration, and neurite outgrowth should uncover novel environmental hazards that may contribute to the etiology of diseases stemming from disruptions in cIN development. Additionally, use of CRISPR/Cas9 technology will enable modeling of known and discovered individual and familial genetic variants and allow for higher throughput analysis of potential gene-environment interactions.

6. Conclusion

The “two-hit” hypothesis states that when a disease cannot be clearly linked to a single genetic predisposition or relevant environmental agent, its etiology is likely multifactorial. In such cases, genetic predisposition may alter individual sensitivity to environmental influences. In recent years, a great number of genetic variants and teratogens have been identified that alter cIN development. However, as neither genetic susceptibility nor environmental exposure alone can accurately predict risk of developing epilepsy, schizophrenia, or autism, the pathology associated with these diseases likely results from intricate interactions between both elements. How environmental factors superimposed with genetic susceptibility contribute to the pathogenesis of seizure disorders and neuropsychiatric illnesses, though, remains to be determined. In addition, the capability of neural circuits to adapt to developmental insults and the mechanisms by which they may do so are not yet understood. Exploring these complex avenues will undoubtedly advance design of effective preventative strategies for a number of common, debilitating conditions. Furthermore, technical advances fueled by understanding of cIN development are quickly making cell culture and grafting therapies imaginable treatments for these devastating disorders166,167.

Highlights.

This review explores the emerging link between common teratogens and abnormal cIN Development

cIN dysfunction is associated with multiple common seizure and neuropsychiatric disorders

Understanding culpable etiological factors will advance treatment and prevention of these diseases

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant T35-OD011078 to LAW from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Drs. Mary Halloran and Timothy Gomez (University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin) for inspiration, and Drs. Ruth Sullivan and Stephen Johnson (University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin) for their thoughtful comments and review.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dreifuss J, Kelly J, Krnjević K. Cortical inhibition and γ-aminobutyric acid. Experimental brain research. 1969;9:137–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00238327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu J, Anderson SA. Development of cortical interneurons. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:16–23. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markram H, et al. Interneurons of the neocortical inhibitory system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:793–807. doi: 10.1038/nrn1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whittington MA, Traub RD. Interneuron diversity series: inhibitory interneurons and network oscillations in vitro. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klausberger T, Somogyi P. Neuronal diversity and temporal dynamics: the unity of hippocampal circuit operations. Science. 2008;321:53–57. doi: 10.1126/science.1149381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X-J, Tegnér J, Constantinidis C, Goldman-Rakic P. Division of labor among distinct subtypes of inhibitory neurons in a cortical microcircuit of working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:1368–1373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305337101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ongür D, Prescot AP, McCarthy J, Cohen BM, Renshaw PF. Elevated gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in chronic schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:667–670. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon JH, et al. GABA concentration is reduced in visual cortex in schizophrenia and correlates with orientation-specific surround suppression. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3777–3781. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.6158-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yizhar O, et al. Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature. 2011;477:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nature10360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bissonette GB, Bae MH, Suresh T, Jaffe DE, Powell EM. Prefrontal cognitive deficits in mice with altered cerebral cortical GABAergic interneurons. Behav Brain Res. 2014;259:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacob J. Cortical interneuron dysfunction in epilepsy associated with autism spectrum disorders. Epilepsia. 2016;57:182–193. doi: 10.1111/epi.13272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashemi E, Ariza J, Rogers H, Noctor SC, Martínez-Cerdeño V. The Number of Parvalbumin-Expressing Interneurons Is Decreased in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex in Autism. Cereb Cortex. 2016 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konstantoudaki X, Chalkiadaki K, Tivodar S, Karagogeos D, Sidiropoulou K. Impaired synaptic plasticity in the prefrontal cortex of mice with developmentally decreased number of interneurons. Neuroscience. 2016;322:333–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takano T. Interneuron Dysfunction in Syndromic Autism: Recent Advances. Dev Neurosci. 2015;37:467–475. doi: 10.1159/000434638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marín O. Interneuron dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:107–120. doi: 10.1038/nrn3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inan M, Petros TJ, Anderson SA. Losing your inhibition: linking cortical GABAergic interneurons to schizophrenia. Neurobiology of disease. 2013;53:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Os J, Rutten BP, Poulton R. Gene-environment interactions in schizophrenia: review of epidemiological findings and future directions. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2008;34:1066–1082. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fazzari P, et al. Control of cortical GABA circuitry development by Nrg1 and ErbB4 signalling. Nature. 2010;464:1376–1380. doi: 10.1038/nature08928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen L, et al. Neuregulin 1 regulates pyramidal neuron activity via ErbB4 in parvalbumin-positive interneurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:1211–1216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910302107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cobos I, et al. Mice lacking Dlx1 show subtype-specific loss of interneurons, reduced inhibition and epilepsy. Nature neuroscience. 2005;8:1059–1068. doi: 10.1038/nn1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson JB, Mednick SA, Huttunen M, Wang X. Prenatal teratogens and the development of adult mental illness. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:457–466. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dufour-Rainfray D, et al. Fetal exposure to teratogens: evidence of genes involved in autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1254–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trentini JF, O’Neill JT, Poluch S, Juliano SL. Prenatal carbon monoxide impairs migration of interneurons into the cerebral cortex. Neurotoxicology. 2016;53:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lussier SJ, Stevens HE. Delays in GABAergic Interneuron Development and Behavioral Inhibition after Prenatal Stress. Dev Neurobiol. 2016 doi: 10.1002/dneu.22376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vargish GA, et al. Persistent inhibitory circuit defects and disrupted social behaviour following in utero exogenous cannabinoid exposure. Mol Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canetta S, et al. Maternal immune activation leads to selective functional deficits in offspring parvalbumin interneurons. Mol Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smiley JF, et al. Selective reduction of cerebral cortex GABA neurons in a late gestation model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Alcohol. 2015;49:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weissman MM, Warner V, Wickramaratne PJ, Kandel DB. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychopathology in offspring followed to adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:892–899. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Services, U.D. o. H. a. H. Women and smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landgren M, Svensson L, Strömland K, Grönlund MA. Prenatal alcohol exposure and neurodevelopmental disorders in children adopted from eastern Europe. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1178–e1185. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peyre E, Silva CG, Nguyen L. Crosstalk between intracellular and extracellular signals regulating interneuron production, migration and integration into the cortex. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:129. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brandão JA, Romcy-Pereira RN. Interplay of environmental signals and progenitor diversity on fate specification of cortical GABAergic neurons. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:149. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Battaglia D, Karagiannis A, Gallopin T, Gutch HW, Cauli B. Beyond the frontiers of neuronal types. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:13. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kepecs A, Fishell G. Interneuron cell types are fit to function. Nature. 2014;505:318–326. doi: 10.1038/nature12983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ascoli GA, et al. Petilla terminology: nomenclature of features of GABAergic interneurons of the cerebral cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9:557–568. doi: 10.1038/nrn2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jessell TM. Neuronal specification in the spinal cord: inductive signals and transcriptional codes. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2000;1:20–29. doi: 10.1038/35049541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puelles L, et al. Pallial and subpallial derivatives in the embryonic chick and mouse telencephalon, traced by the expression of the genes Dlx‐2, Emx‐1, Nkx‐2.1, Pax‐6, and Tbr‐1. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2000;424:409–438. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000828)424:3<409::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marin O, Rubenstein JL. Mouse Development: Patterning, Morphogenesis, and Organogenesis. Academic Press; San Diego: 2002. Patterning, regionalization, and cell differentiation in the forebrain; pp. 75–106. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flames N, Marín O. Developmental mechanisms underlying the generation of cortical interneuron diversity. Neuron. 2005;46:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu Q, Cobos I, De La Cruz E, Rubenstein JL, Anderson SA. Origins of cortical interneuron subtypes. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2612–2622. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.5667-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butt SJB, et al. The temporal and spatial origins of cortical interneurons predict their physiological subtype. Neuron. 2005;48:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flames N, et al. Delineation of multiple subpallial progenitor domains by the combinatorial expression of transcriptional codes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9682–9695. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2750-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyoshi G, Butt SJB, Takebayashi H, Fishell G. Physiologically distinct temporal cohorts of cortical interneurons arise from telencephalic Olig2-expressing precursors. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7786–7798. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.1807-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Butt SJB, et al. The requirement of Nkx2-1 in the temporal specification of cortical interneuron subtypes. Neuron. 2008;59:722–732. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wonders CP, et al. A spatial bias for the origins of interneuron subgroups within the medial ganglionic eminence. Dev Biol. 2008;314:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Welagen J, Anderson S. Origins of neocortical interneurons in mice. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71:10–17. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inan M, Welagen J, Anderson SA. Spatial and temporal bias in the mitotic origins of somatostatin- and parvalbumin-expressing interneuron subgroups and the chandelier subtype in the medial ganglionic eminence. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22:820–827. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tricoire L, et al. Common origins of hippocampal Ivy and nitric oxide synthase expressing neurogliaform cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2165–2176. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.5123-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelsom C, Lu W. Development and specification of GABAergic cortical interneurons. Cell & bioscience. 2013;3:1. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rudy B, Fishell G, Lee S, Hjerling‐Leffler J. Three groups of interneurons account for nearly 100% of neocortical GABAergic neurons. Developmental neurobiology. 2011;71:45–61. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cruikshank SJ, Lewis TJ, Connors BW. Synaptic basis for intense thalamocortical activation of feedforward inhibitory cells in neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:462–468. doi: 10.1038/nn1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gabernet L, Jadhav SP, Feldman DE, Carandini M, Scanziani M. Somatosensory integration controlled by dynamic thalamocortical feed-forward inhibition. Neuron. 2005;48:315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vucurovic K, et al. Serotonin 3A receptor subtype as an early and protracted marker of cortical interneuron subpopulations. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:2333–2347. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miyoshi G, et al. Prox1 regulates the subtype-specific development of caudal ganglionic eminence-derived GABAergic cortical interneurons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35:12869–12889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1164-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee S, Hjerling-Leffler J, Zagha E, Fishell G, Rudy B. The largest group of superficial neocortical GABAergic interneurons expresses ionotropic serotonin receptors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16796–16808. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.1869-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson SA, Eisenstat DD, Shi L, Rubenstein JL. Interneuron migration from basal forebrain to neocortex: dependence on Dlx genes. Science. 1997;278:474–476. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wichterle H, Turnbull DH, Nery S, Fishell G, Alvarez-Buylla A. In utero fate mapping reveals distinct migratory pathways and fates of neurons born in the mammalian basal forebrain. Development. 2001;128:3759–3771. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gelman DM, et al. The embryonic preoptic area is a novel source of cortical GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9380–9389. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0604-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nery S, Corbin JG, Fishell G. Dlx2 progenitor migration in wild type and Nkx2. 1 mutant telencephalon. Cerebral Cortex. 2003;13:895–903. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.9.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miyoshi G, et al. Genetic fate mapping reveals that the caudal ganglionic eminence produces a large and diverse population of superficial cortical interneurons. The Journal of neuroscience. 2010;30:1582–1594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4515-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Otis EM, Brent R. Equivalent ages in mouse and human embryos. The Anatomical record. 1954;120:33–63. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hansen DV, et al. Non-epithelial stem cells and cortical interneuron production in the human ganglionic eminences. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16:1576–1587. doi: 10.1038/nn.3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jakovcevski I, Mayer N, Zecevic N. Multiple origins of human neocortical interneurons are supported by distinct expression of transcription factors. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:1771–1782. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Long JE, Cobos I, Potter GB, Rubenstein JL. Dlx1&2 and Mash1 transcription factors control MGE and CGE patterning and differentiation through parallel and overlapping pathways. Cerebral cortex. 2009 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp045. bhp045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petryniak MA, Potter GB, Rowitch DH, Rubenstein JL. Dlx1 and Dlx2 control neuronal versus oligodendroglial cell fate acquisition in the developing forebrain. Neuron. 2007;55:417–433. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cobos I, Borello U, Rubenstein JL. Dlx transcription factors promote migration through repression of axon and dendrite growth. Neuron. 2007;54:873–888. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Urbanska M, Blazejczyk M, Jaworski J. Molecular basis of dendritic arborization. Acta neurobiologiae experimentalis. 2008;68:264. doi: 10.55782/ane-2008-1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Le TN, et al. Dlx homeobox genes promote cortical interneuron migration from the basal forebrain by direct repression of the semaphorin receptor neuropilin-2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:19071–19081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Du T, Xu Q, Ocbina PJ, Anderson SA. NKX2.1 specifies cortical interneuron fate by activating Lhx6. Development. 2008;135:1559–1567. doi: 10.1242/dev.015123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fuccillo M, Rallu M, McMahon AP, Fishell G. Temporal requirement for hedgehog signaling in ventral telencephalic patterning. Development. 2004;131:5031–5040. doi: 10.1242/dev.01349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu Q, Wonders CP, Anderson SA. Sonic hedgehog maintains the identity of cortical interneuron progenitors in the ventral telencephalon. Development. 2005;132:4987–4998. doi: 10.1242/dev.02090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sussel L, Marin O, Kimura S, Rubenstein JL. Loss of Nkx2.1 homeobox gene function results in a ventral to dorsal molecular respecification within the basal telencephalon: evidence for a transformation of the pallidum into the striatum. Development. 1999;126:3359–3370. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liodis P, et al. Lhx6 activity is required for the normal migration and specification of cortical interneuron subtypes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3078–3089. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.3055-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neves G, et al. The LIM homeodomain protein Lhx6 regulates maturation of interneurons and network excitability in the mammalian cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2012 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs159. bhs159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Volk DW, et al. Deficits in transcriptional regulators of cortical parvalbumin neurons in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1082–1091. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Denaxa M, et al. Maturation-promoting activity of SATB1 in MGE-derived cortical interneurons. Cell reports. 2012;2:1351–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gelman D, et al. A wide diversity of cortical GABAergic interneurons derives from the embryonic preoptic area. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:16570–16580. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4068-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xu Q, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling confers ventral telencephalic progenitors with distinct cortical interneuron fates. Neuron. 2010;65:328–340. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Petros TJ, Bultje RS, Ross ME, Fishell G, Anderson SA. Apical versus Basal Neurogenesis Directs Cortical Interneuron Subclass Fate. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1090–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guo J, Anton ES. Decision making during interneuron migration in the developing cerebral cortex. Trends in cell biology. 2014;24:342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rudolph J, Zimmer G, Steinecke A, Barchmann S, Bolz J. Ephrins guide migrating cortical interneurons in the basal telencephalon. Cell adhesion & migration. 2010;4:400–408. doi: 10.4161/cam.4.3.11640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marín O, et al. Directional guidance of interneuron migration to the cerebral cortex relies on subcortical Slit1/2-independent repulsion and cortical attraction. Development. 2003;130:1889–1901. doi: 10.1242/dev.00417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Powell EM, Mars WM, Levitt P. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor is a motogen for interneurons migrating from the ventral to dorsal telencephalon. Neuron. 2001;30:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sánchez-Huertas C, Rico B. CREB-dependent regulation of GAD65 transcription by BDNF/TrkB in cortical interneurons. Cerebral Cortex. 2011;21:777–788. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pozas E, Ibáñez CF. GDNF and GFRα1 promote differentiation and tangential migration of cortical GABAergic neurons. Neuron. 2005;45:701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Polleux F, Whitford KL, Dijkhuizen PA, Vitalis T, Ghosh A. Control of cortical interneuron migration by neurotrophins and PI3-kinase signaling. Development. 2002;129:3147–3160. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.13.3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tiveron M-C, et al. Molecular interaction between projection neuron precursors and invading interneurons via stromal-derived factor 1 (CXCL12)/CXCR4 signaling in the cortical subventricular zone/intermediate zone. The Journal of neuroscience. 2006;26:13273–13278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4162-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Flames N, et al. Short-and long-range attraction of cortical GABAergic interneurons by neuregulin-1. Neuron. 2004;44:251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bortone D, Polleux F. KCC2 expression promotes the termination of cortical interneuron migration in a voltage-sensitive calcium-dependent manner. Neuron. 2009;62:53–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rymar VV, Sadikot AF. Laminar fate of cortical GABAergic interneurons is dependent on both birthdate and phenotype. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501:369–380. doi: 10.1002/cne.21250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Torigoe M, Yamauchi K, Kimura T, Uemura Y, Murakami F. Evidence That the Laminar Fate of LGE/CGE-Derived Neocortical Interneurons Is Dependent on Their Progenitor Domains. J Neurosci. 2016;36:2044–2056. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.3550-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Miyoshi G, Fishell G. GABAergic interneuron lineages selectively sort into specific cortical layers during early postnatal development. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:845–852. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ciceri G, et al. Lineage-specific laminar organization of cortical GABAergic interneurons. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16:1199–1210. doi: 10.1038/nn.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brown KN, et al. Clonal production and organization of inhibitory interneurons in the neocortex. Science. 2011;334:480–486. doi: 10.1126/science.1208884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lodato S, et al. Excitatory projection neuron subtypes control the distribution of local inhibitory interneurons in the cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2011;69:763–779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Steriade M, Timofeev I, Dürmüller N, Grenier F. Dynamic properties of corticothalamic neurons and local cortical interneurons generating fast rhythmic (30–40 Hz) spike bursts. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:483–490. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Muhle R, Trentacoste SV, Rapin I. The genetics of autism. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e472–e486. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Farrell M, et al. Evaluating historical candidate genes for schizophrenia. Molecular psychiatry. 2015;20:555–562. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Myers CT, Mefford HC. Advancing epilepsy genetics in the genomic era. Genome medicine. 2015;7:1. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0214-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bassett AS, Marshall CR, Lionel AC, Chow EW, Scherer SW. Copy number variations and risk for schizophrenia in 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Human molecular genetics. 2008;17:4045–4053. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Meechan DW, Tucker ES, Maynard TM, LaMantia A-S. Diminished dosage of 22q11 genes disrupts neurogenesis and cortical development in a mouse model of 22q11 deletion/DiGeorge syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:16434–16445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905696106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Murphy KC, Jones LA, Owen MJ. High rates of schizophrenia in adults with velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Archives of general psychiatry. 1999;56:940–945. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tsuang MT, Stone WS, Faraone SV. Genes, environment and schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;178:s18–s24. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.40.s18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Folstein S. Twin and adoption studies in child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1996;8:339–347. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199608000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Berkovic SF, Howell RA, Hay DA, Hopper JL. Epilepsies in twins: genetics of the major epilepsy syndromes. Annals of neurology. 1998;43:435–445. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bianchi A, et al. Concordance of clinical forms of epilepsy in families with several affected members. Epilepsia. 1993;34:819–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mason-Brothers A, Mo A, Ritvo AM. Concordance for the syndrome of autism in 40 pairs of afflicted twins. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:74–77. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rosenberg RE, et al. Characteristics and concordance of autism spectrum disorders among 277 twin pairs. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2009;163:907–914. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ibi D, et al. Combined effect of neonatal immune activation and mutant DISC1 on phenotypic changes in adulthood. Behavioural brain research. 2010;206:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Prevention C. f. D. C. a. Alcohol use binge drinking among women of childbearing age–United States, 2006–2010. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2012;61:534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stockard C. The influence of alcohol and other anaesthetics on embryonic development. Am J Anat. 1910;10:369–392. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Coriale G, et al. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD): neurobehavioral profile, indications for diagnosis and treatment. Rivista di psichiatria. 2013;48:359–369. doi: 10.1708/1356.15062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bell SH, et al. The remarkably high prevalence of epilepsy and seizure history in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1084–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Granato A. Altered organization of cortical interneurons in rats exposed to ethanol during neonatal life. Brain research. 2006;1069:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cuzon VC, Yeh PW, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Yeh HH. Ethanol consumption during early pregnancy alters the disposition of tangentially migrating GABAergic interneurons in the fetal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:1854–1864. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5110-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Godin EA, Dehart DB, Parnell SE, O’Leary-Moore SK, Sulik KK. Ventromedian forebrain dysgenesis follows early prenatal ethanol exposure in mice. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 2011;33:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Skorput AG, Gupta VP, Yeh PW, Yeh HH. Persistent interneuronopathy in the prefrontal cortex of young adult offspring exposed to ethanol in utero. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35:10977–10988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1462-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Skorput AG, Yeh HH, Chronic Gestational. Exposure to Ethanol Leads to Enduring Aberrances in Cortical Form and Function in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016 doi: 10.1111/acer.13107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.May PA, et al. Maternal risk factors predicting child physical characteristics and dysmorphology in fetal alcohol syndrome and partial fetal alcohol syndrome. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2011;119:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.May PA, et al. Maternal factors predicting cognitive and behavioral characteristics of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP. 2013;34:314. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182905587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Krauss RS, Hong M. Gene–Environment Interactions the Etiology of Birth Defects. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Eberhart JK, Parnell SE. The genetics of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016 doi: 10.1111/acer.13066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kietzman HW, Everson JL, Sulik KK, Lipinski RJ. The teratogenic effects of prenatal ethanol exposure are exacerbated by Sonic Hedgehog or GLI2 haploinsufficiency in the mouse. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lipinski RJ, et al. Ethanol-induced face-brain dysmorphology patterns are correlative and exposure-stage dependent. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yamada Y, Nagase T, Nagase M, Koshima I. Gene expression changes of sonic hedgehog signaling cascade in a mouse embryonic model of fetal alcohol syndrome. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2005;16:1055–1061. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000183470.31202.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ahlgren SC, Thakur V, Bronner-Fraser M. Sonic hedgehog rescues cranial neural crest from cell death induced by ethanol exposure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:10476–10481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162356199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Li Y-X, et al. Fetal alcohol exposure impairs Hedgehog cholesterol modification and signaling. Laboratory investigation. 2007;87:231–240. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wang J, et al. The insecticide synergist piperonyl butoxide inhibits Hedgehog signaling: assessing chemical risks. Toxicological Sciences. 2012:kfs165. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lipinski RJ, Dengler E, Kiehn M, Peterson RE, Bushman W. Identification and characterization of several dietary alkaloids as weak inhibitors of hedgehog signaling. Toxicological sciences. 2007;100:456–463. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tong VT, et al. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 sites, 2000–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:S125–S140. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Chen L, Jones J. Is maternal smoking during pregnancy a risk factor for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children? The American journal of psychiatry. 1996;153:1138. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.9.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Jones J. Further evidence of an association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings from a high-risk sample of siblings. Journal of clinical child psychology. 1998;27:352–358. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2703_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wakschlag LS, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and the risk of conduct disorder in boys. Archives of general psychiatry. 1997;54:670–676. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830190098010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wakschlag LS, Pickett KE, Cook E, Jr, Benowitz NL, Leventhal BL. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and severe antisocial behavior in offspring: a review. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:966–974. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Eisenberg HM, Albuquerque EX. Nicotinic receptor activation in human cerebral cortical interneurons: a mechanism for inhibition and disinhibition of neuronal networks. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:66–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00066.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Abuse S, Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. (Summary of National Findings (No. NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No.(SMA) 13-4795)). 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Calvigioni D, Hurd YL, Harkany T, Keimpema E. Neuronal substrates and functional consequences of prenatal cannabis exposure. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23:931–941. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0550-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Harkany T, et al. The emerging functions of endocannabinoid signaling during CNS development. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2007;28:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Fertuzinhos S, et al. Selective depletion of molecularly defined cortical interneurons in human holoprosencephaly with severe striatal hypoplasia. Cerebral cortex. 2009;19:2196–2207. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zhu J, Xu W, Angulo J. Methamphetamine-induced cell death: selective vulnerability in neuronal subpopulations of the striatum in mice. Neuroscience. 2006;140:607–622. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Toriumi K, et al. Prenatal phencyclidine treatment induces behavioral deficits through impairment of GABAergic interneurons in the prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology. 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4288-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.McCarthy DM, Bhide PG. Prenatal cocaine exposure decreases parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons and GABA-to-projection neuron ratio in the medial prefrontal cortex. Dev Neurosci. 2012;34:174–183. doi: 10.1159/000337172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Crandall JE, Hackett HE, Tobet SA, Kosofsky BE, Bhide PG. Cocaine exposure decreases GABA neuron migration from the ganglionic eminence to the cerebral cortex in embryonic mice. Cerebral Cortex. 2004;14:665–675. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Williams G, et al. Fetal valproate syndrome and autism: additional evidence of an association. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2001;43:202–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Rasalam A, et al. Characteristics of fetal anticonvulsant syndrome associated autistic disorder. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2005;47:551–555. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205001076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Rinaldi T, Silberberg G, Markram H. Hyperconnectivity of local neocortical microcircuitry induced by prenatal exposure to valproic acid. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18:763–770. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Guirado R, Perez-Rando M, Sanchez-Matarredona D, Castrén E, Nacher J. Chronic fluoxetine treatment alters the structure, connectivity and plasticity of cortical interneurons. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;17:1635–1646. doi: 10.1017/S1461145714000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Ohira K, Takeuchi R, Iwanaga T, Miyakawa T. Chronic fluoxetine treatment reduces parvalbumin expression and perineuronal netsin gamma-aminobutyric acidergic interneurons of the frontal cortex in adultmice. Molecular brain. 2013;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Morrison JL, Riggs KW, Rurak DW. Fluoxetine during pregnancy: impact on fetal development. Reproduction, Fertility and Development. 2005;17:641–650. doi: 10.1071/rd05030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Olivier JD, et al. Fluoxetine administration to pregnant rats increases anxiety-related behavior in the offspring. Psychopharmacology. 2011;217:419–432. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2299-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Geddes JR, et al. Schizophrenia and complications of pregnancy and labor: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Schizophrenia bulletin. 1999;25:413–423. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Stevens HE, Su T, Yanagawa Y, Vaccarino FM. Prenatal stress delays inhibitory neuron progenitor migration in the developing neocortex. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:509–521. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Matrisciano F, et al. Epigenetic modifications of GABAergic interneurons are associated with the schizophrenia-like phenotype induced by prenatal stress in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2013;68:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Liang D, et al. Developmental loss of parvalbumin-positive cells in the prefrontal cortex and psychiatric anxiety after intermittent hypoxia exposures in neonatal rats might be mediated by NADPH oxidase-2. Behavioural brain research. 2016;296:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Zuckerman L, Weiner I. Maternal immune activation leads to behavioral and pharmacological changes in the adult offspring. Journal of psychiatric research. 2005;39:311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Patterson PH. Maternal infection and immune involvement in autism. Trends in molecular medicine. 2011;17:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Ellman LM, Susser ES. The promise of epidemiologic studies: neuroimmune mechanisms in the etiologies of brain disorders. Neuron. 2009;64:25–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Brown AS. Prenatal infection as a risk factor for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2006;32:200–202. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Driggers RW, et al. Zika virus infection with prolonged maternal viremia and fetal brain abnormalities. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Ryan KR, et al. Neurite outgrowth in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons as a high-throughput screen for developmental neurotoxicity or neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology. 2016;53:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Hondebrink L, et al. Neurotoxicity screening of (illicit) drugs using novel methods for analysis of microelectrode array (MEA) recordings. Neurotoxicology. 2016;55:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Mariani J, et al. Modeling human cortical development in vitro using induced pluripotent stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:12770–12775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202944109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Goulburn AL, Stanley EG, Elefanty AG, Anderson SA. Generating GABAergic cerebral cortical interneurons from mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Stem cell research. 2012;8:416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Liu Y, et al. Directed differentiation of forebrain GABA interneurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Nature protocols. 2013;8:1670–1679. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Shetty AK, Upadhya D. GABA-ergic cell therapy for epilepsy: Advances, limitations and challenges. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2016;62:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]