ABSTRACT

Background: Community health workers (CHWs) can play vital roles in increasing coverage of basic health services. However, there is a need for a systematic categorisation of CHWs that will aid common understanding among policy makers, programme planners, and researchers.

Objective: To identify the common themes in the definitions and descriptions of CHWs that will aid delineation within this cadre and distinguish CHWs from other healthcare providers.

Design: A systematic review of peer-reviewed papers and grey literature.

Results: We identified 119 papers that provided definitions of CHWs in 25 countries across 7 regions. The review shows CHWs as paraprofessionals or lay individuals with an in-depth understanding of the community culture and language, have received standardised job-related training of a shorter duration than health professionals, and their primary goal is to provide culturally appropriate health services to the community. CHWs can be categorised into three groups by education and pre-service training. These are lay health workers (individuals with little or no formal education who undergo a few days to a few weeks of informal training), level 1 paraprofessionals (individuals with some form of secondary education and subsequent informal training), and level 2 paraprofessionals (individuals with some form of secondary education and subsequent formal training lasting a few months to more than a year). Lay health workers tend to provide basic health services as unpaid volunteers while level 1 paraprofessionals often receive an allowance and level 2 paraprofessionals tend to be salaried.

Conclusions: This review provides a categorisation of CHWs that may be useful for health policy formulation, programme planning, and research.

KEYWORDS: Lay health worker, health workforce, role, scope of practice

Background

To achieve the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and universal health coverage (UHC) in the post-2015 period, adequate numbers of competent health workers are required to provide services in an enabling environment [1]. A decade ago, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a crisis in the global health workforce, characterised by severe shortages, inappropriate skill mixes, and gaps in service coverage [2]. The magnitude of the health workforce shortage varies across contexts with rural regions and low- and middle-income countries being the worst affected, and with critical shortages greatest in sub-Saharan Africa [3].

Evidence suggests that the presence of community health workers (CHWs) can complement an overstretched health workforce and may be key to increasing the availability of, and access to, basic health services especially in hard-to-reach areas, thereby bridging the health equity gap [4,5]. However, the diversity of roles and inconsistent nomenclature of CHWs make it difficult for policy makers, programme planners, and researchers working with CHWs in different settings to have a common understanding of ‘who is a CHW?’ [6]. Furthermore, in contrast to professional health workers, there is remarkable diversity in the content and duration of CHWs’ training. Some CHWs undergo informal training, with varied training content and durations, taking place outside recognised training institutions. Other CHWs undergo formal training in nationally recognised training institutions with structured training content and duration [7,8].

There have been different attempts to define and categorise CHWs based on their roles, educational level, and remuneration [5,9]. However, there is a need to build on these approaches by using a methodical approach that accommodates the diversities in CHW definitions to identify the spectrum of CHW categories that will aid comparison with other groups of health workers. Health worker categories that are comparable across disciplines may be crucial to designing CHW roles and positions within multidisciplinary health teams [10].

We conducted a systematic review of the global literature in order to: (1) identify definitions of CHWs reported in the literature; (2) determine key themes in how definitions are reported; and (3) clarify use of the term CHW for policy makers.

Methods

Selection criteria

We included any type of paper that described CHWs, their roles, and ways of working; this included published peer-reviewed primary research as well as commentaries, editorials, and review papers. For primary research, we included studies from any discipline using any study design and methods. We also included grey literature (unpublished reports and evaluations) if it included descriptions of CHWs or explanations of their roles. We included literature that described CHWs working in any aspect of primary or community healthcare and any disease or health issue. Overall, we included published and unpublished papers reported in English. In contrast, we excluded papers not focused on CHWs or papers that focused on CHWs but lacked a definition or description of CHWs. Furthermore, we excluded papers that are not reported in the English language.

Search strategy

We searched eight databases for peer-reviewed literature (CHW Central, CINAHL Plus, ERIC, Global Health, LILACS, MEDLINE, Popline, and Web of Science); two of these databases also contained grey literature (CHW Central and Popline). Keywords for the search included terms for CHW (e.g. ‘community health worker*’ and alternate terms for ‘CHWs’) and a term for definition (e.g. ‘defin*’). We identified a total of 66 alternate terms for CHWs through a preliminary literature search and database subject headings (see Supplemental File 1 for an example of the search conducted in MEDLINE). We excluded terms which can be classified as ‘health professional’ as defined by the WHO’s mapping of occupations [11]. We limited the database searches to literature published in English between January 2004 and March 2016. The first global report on the global health workforce crisis was published in 2004; this emphasised the inclusion of CHWs in country health plans and resulted in a renewed interest in CHWs and subsequently additional research and publications on the topic [12].

We also hand-searched the references of all identified papers to find further relevant literature containing definitions or descriptions of CHWs. When the full text was not available online (n = 2 papers), we contacted the primary authors by email to request a copy. Both primary authors provided electronic copies of the papers that were not available online.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts (or executive summaries) of 7,653 sources identified in the various databases were reviewed independently by two of the authors (AO and RU) to identify potentially relevant papers. The same authors obtained and independently reviewed the full text of 783 potentially relevant papers. When there was no consensus on inclusion or exclusion of a paper (n = 1), they sought the opinion of a third reviewer (NvdB).

Data synthesis

We used narrative synthesis [13] to summarise definitions and other information contained in the included papers in a structured way. We extracted information on the characteristics of the study and definitions of CHWs using standard tables which were then used to make comparisons across included papers. Using an inductive approach, we reviewed the definitions for reoccurring patterns of items that relate to our study objectives; these formed our codes (Supplemental File 3). We reviewed these codes for concepts that are related in meaning, thereby constituting sub-themes, and subsequently we grouped sub-themes with similar connotations into themes: (1) selection criteria, (2) roles and/or tasks, (3) training, and (4) remuneration. Finally, we compared the themes, sub-themes, and codes for congruency in meaning and developed narratives to describe the various themes and sub-themes.

Results

Description of included papers

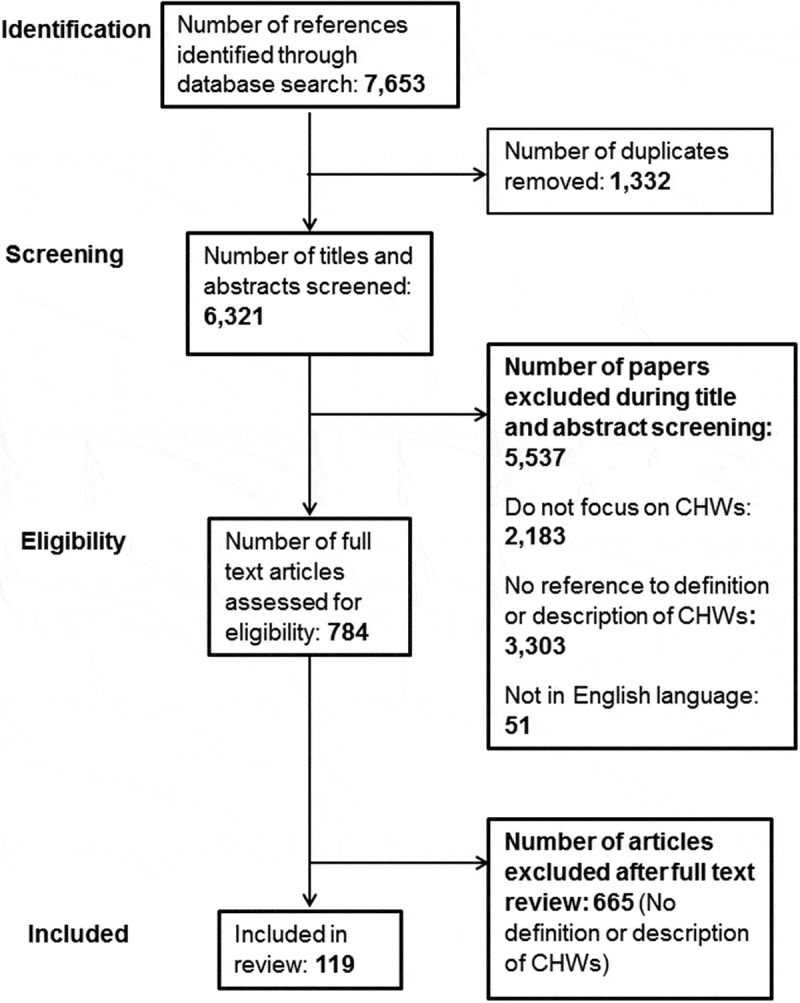

Figure 1 illustrates the process of study selection. The database searches identified 7,653 references; from these, we removed 1,332 duplicates. From the remaining 6,321 titles and abstracts, we excluded 5,537 as they were not in English or did not focus on CHWs. Of the 783 full text papers reviewed, we excluded 664 as they did not provide a definition or description of CHWs, leaving 119 included papers (Figure 1). Of the 119 included papers, 110 are peer-reviewed publications and 9 are grey reports or non-peer-reviewed papers. Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the 119 included papers; a full detailed list of the included papers and their characteristics is provided in Supplemental File 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of included papers (n = 119).

| Region | Income group | Year of publication | Type of publication | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Asia & Pacific | 3 | High-income | 62 | 2004–2009 | 19 | Peer-reviewed | 110 |

| Europe & Central Asia | 3 | Upper middle-income | 10 | 2010–2016 | 100 | Grey literature | 9 |

| Latin America & the Caribbean | 4 | Low-income | 16 | ||||

| Middle East & North Africa | 1 | Multiple: across all income groups | 16 | ||||

| North America | 59 | Lower middle-income | 15 | ||||

| South Asia | 13 | ||||||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 20 | ||||||

| Multiple countries | 16 |

The majority (n = 100) of the papers documenting definitions of CHWs were published in the latter half of the review period (2010–2016) (Table 1). The included papers described CHWs in 25 countries across 7 regions and all income groups as defined by the World Bank [14]. Sixty-two (52%) of the included papers described CHWs in high-income countries, 10 (8%) in upper middle-income countries, 15 in (13%) lower middle-income countries, and 16 (13%) in low-income countries. Sixteen papers described CHWs in more than one country.

Description of findings

Common themes identified in definitions or descriptions of CHWs are outlined in Supplemental Table 3. The common themes in definitions of CHWs include (1) selection criteria, (2) roles and/or tasks, (3) training, and (4) remuneration.

Table 3.

Pattern of educational qualification, pre-service training, and remuneration of CHW categories.

| Remuneration |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational qualification and pre-service training | Unpaid | Either unpaid or receive allowance/incentives | Receive allowance/incentives | Salaried |

| Individuals with minimal or no previous education and a few days to a few weeks of job-related pre-service training outside a recognised training institution | [22,90,116] | [53,78,124] | ||

| Individuals with some secondary education and subsequent pre-service training outside a recognised training institution lasting a few months to more than a year | [35,92] | |||

| Individuals with some secondary education and subsequent pre-service training in a recognised training institution lasting a few months to more than a year | [27,46,120] | |||

Selection of CHWs

Overall, more than half (n = 82) of the included papers described CHWs in relation to how they are selected from the community. Papers generally reported the selection criteria and the organisations or institutions involved in CHWs’ selection. Overall, CHWs are selected based on community membership, knowledge of the community culture and languages spoken, personality traits that encourage trust and respect, gender, previous experience providing healthcare, and educational qualification (Table 2).

Table 2.

Variation in the selection criteria used by stakeholders.

| |

Criteria used in selection of CHWs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organisation or institution involved in selection | Reside in the community | Personality traits that engender trust and respect | Previous experience providing healthcare | Educational qualification |

| Community | [15–18,19,20,21] | [21] | ||

| NGOs | [22] | |||

| Health facility management | [23,24] | [24] | ||

| Community and government | [25] | [25] | ||

| Government | [26] | [26,27] | ||

Many of the included papers noted that CHWs are selected because they are community residents, who may not be indigenes of the community [15,22,28–37], or they are indigenous members residing in the community [16–20,25,26,38–72]. CHWs are also expected to have a close understanding or share the ethnicity, language [23,39,41–44,50,59,61,73–85], socioeconomic status [6,39,53,76,78], and life experiences [6,39,53,76,78,84] of the community. It is anticipated that these characteristics will ensure that CHWs can better mobilise and increase community members’ acceptance of the health services provided [61,64]. Some papers specified that CHWs should be trusted and respected community members [41,59,61,63,65,75,84,86,87], while in some contexts, CHWs are expected to possess leadership qualities [21,57,88].

In addition to these attributes, CHWs are expected to have other characteristics to better suit them for the role. In general, CHWs providing health services to women and children tend to be female [15,16,18,21,27,37,39,43,52,89–92] and those providing services in a health facility may be required to have some form of healthcare experience [23,24]. Previous primary or secondary education is sometimes considered in the selection of CHWs [24,28,29,46].

There are various organisations or institutions involved in the selection of CHWs. The included papers suggest that CHWs are either selected by the community members and leaders [15–21,28], the relevant department in the Ministry of Health on behalf of the government [29,39,47], non-governmental organisations (NGOs) [22], or by the health facility management [23,24]. The selection criteria, however, tend to vary across these stakeholder groups (Table 2). Being a resident of the community and having personality traits that engender trust and respect are often considered by the community and NGOs when selecting CHWs [15–22,38]. The CHWs selected by the government (or in collaboration with the community) are often selected on the basis of residence in the community and having some form of secondary education [25–27,29,39,93]. Health facility management often select CHWs on the basis of their level of education and having previous work experience in providing healthcare [23,24].

The roles and tasks of CHWs

More than three-quarters (n = 90) of the included papers described the roles and/or tasks of CHWs in the community or within the health facility (Supplemental File 3). The roles of CHWs include health promotion and disease prevention, treatment of basic medical conditions, and collection of health data.

In relation to health promotion and disease prevention, CHWs are involved in activities both within the community and linked to the health facilities they are connected to. In the community, CHWs provide services to promote a healthy lifestyle and prevent disease [17,19,26,28,33,38,40,43,45,56,57,66,67,70,71,73,79,89,90,93–104], mobilise and encourage community members to utilise available health services [15,18,95,103,104], and facilitate access to facility-based healthcare by helping community members understand where to access care when needed [6,15,17,25,26,36,40,43,47,52,56,59,61,63–65,70,72,82,91,104–108]. Acting as ‘Patient Navigators’ [23,24,40,77,80,109–119], CHWs interpret health information and provide logistical support to patients accessing healthcare within a complex healthcare system. They also communicate health messages to community members [6,16,19,33,49,56,60,62,70,73,74,82–86,88,102,104,114,117,119–123], help patients to cope better with clinical conditions by providing psychosocial support [24,41,43,47,49,58,60,73,82,86,96,106,107], and serve as community representatives, providing a link between the community and health system [47,59,74,81,82,84,89,95,96,98,120]. Their role as a community representative entails conveying policy-related health messages to the community members and, in turn, reporting on community health needs and priorities to the health facilities they are linked to.

Some CHWs have additional roles of providing treatment for basic clinical conditions and minor ailments such as malaria and diarrhoea [15,38,39,44,55,95,99,122]. Other CHWs provide basic obstetric case management but the CHWs providing this have completed post-secondary formal training in order to provide these services [28,30,32,52]. Treatment of basic clinical conditions and management of basic obstetric cases appear to be part of a CHW’s role in low- and middle-income countries only; we did not find any evidence of CHWs providing these services in the papers from high-income countries.

The included papers suggest that CHWs also have a role in helping to collect and report, via existing mechanisms, information on the health status of the community members [30,59,93,97].

Educational qualification and pre-service training of CHWs

Less than 20% (n = 21) of the included papers documented the educational qualifications or pre-service training of CHWs in the definitions used (Supplemental File 2). We identified three main patterns in the educational qualification and pre-service training of CHWs:

Individuals with little or no formal education who have undergone a few days to a few weeks of job-related pre-service training outside a recognised training institution (e.g. training provided in a health facility by NGOs) [4,19,21,43,50,53,91,99,123,124].

Individuals with some form of secondary education and subsequent job-related pre-service training outside a recognised training institution lasting any time from a few days to a few weeks [35,92].

Individuals with some form of secondary education and subsequent pre-service training in a recognised training institution lasting a few months to more than a year [18,26,27,32,39,46,52,68,125–127].

Remuneration of CHWs

Some CHWs perform their tasks as unpaid volunteers [18,22,89,90,97,103,108,116,128]. Other CHWs are paid an allowance [19,21,49,94,99], performance-based incentives [35,92], or a formal salary [27,29,39,46,93,126] (Table 3). The form of remuneration is often influenced by the level of educational qualification and form of CHWs’ pre-service training (Table 3). CHWs with minimal or no education and subsequent informal pre-service training are likely to be unpaid or receive an allowance while CHWs with some form of secondary education with subsequent informal pre-service training are likely to receive some allowance or monetary incentive [35,92]. Conversely, CHWs with some secondary education and subsequent formal pre-service training are often salaried and paid by the government [27,46,126].

CHWs’ service recipients

The service recipients of CHWs tend to vary with country income status (Supplemental File 3). In high-income countries, CHWs provide health services to ethnic minority and low-income populations within these countries [21,23,33,41,42,45,47–50,56–60,62,63,74–80,84–86,97,101,107,108,110,113,115,118–120,123]. The service recipients in these settings are usually individuals with non-communicable diseases such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes [23,24,31,33,41,47–49,56,58,63,73,77,80,85,96,100,101,106,109,112,113,115–117,120]. Only one paper from a high-income country (United States) noted that CHWs provide health services related to communicable diseases [129] and four documented maternal and child health services to ethnic minority populations in the United States [42,43,88,114].

Conversely, in low- and middle-income countries, CHWs tend to provide services related to communicable diseases [19,22,28,35,44,55,98,99,128] and maternal and child health services [16–18,26–28,30,32,34,51,52,81,89–92,94,125,127,130,131]. Only two of the included papers from upper middle-income countries (Iran and South Africa) stated that CHWs provide services related to non-communicable diseases [46,121].

Discussion

This review explores the various definitions and descriptions of ‘community health workers’ and identified the common themes in these definitions to understand the essential characteristics of health workers classified as CHWs. Our intention was to describe the various categories of CHWs to help clarify use of the term and reach a common understanding among key stakeholders in community health programme planning, policy, and research.

Common themes in the definitions of CHWs

Our review shows that CHWs engage in health promotion and disease prevention including basic treatment and collecting community health information. Most of the included definitions of CHWs are based on roles and tasks of CHWs. Role-based classification has been used by other authors including a review of global literature which classified CHWs as specialists (have fewer health roles within a defined thematic area) and generalists (have more health roles across thematic areas) [5]. Other studies [132,133], however, show that many governmental organisations and NGOs continue to formally or informally add tasks to the job description of CHWs, thereby blurring distinctions between CHWs who are generalists or specialists. There are suggestions that the definitions and categories of health workers should be based on competency or educational qualification rather than on tasks or roles [10]. In general, categorisations of health workers tend to be competency-based as the level of competency usually informs the type of tasks assigned to any group of health workers and their position within the health system. This competency-based categorisation may be key to developing frameworks to aid common understanding among stakeholders irrespective of context and comparison of different groups of health workers. Furthermore, these categories may assist programme planners in designing job profiles for multidisciplinary health teams and assigning commensurate remuneration based on competency levels [134].

In line with our review findings, the level of competency and educational qualification of health workers will often determine roles/tasks, selection/recruitment, and remuneration [135].

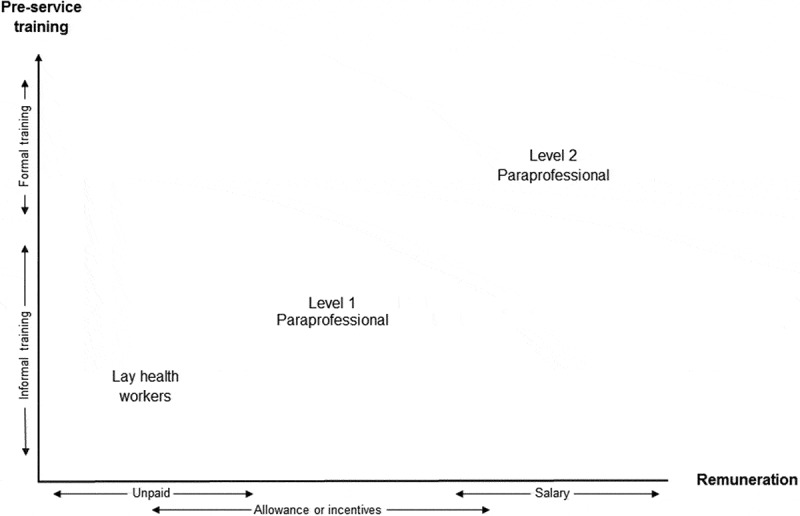

Through this review, we found that the level of competency or qualifications used for categorising health workers varies across settings, as found in other research [136]. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) suggest that lay health workers may or may not possess basic literacy skills while paraprofessionals are individuals who have had some form of formal long-duration post-secondary (non-tertiary) education and professionals usually have some form of tertiary education [137]. We modified the ILO definition of paraprofessionals to accommodate the two levels of competency of CHWs who may be classified as paraprofessionals. These are level 2 paraprofessionals, who are individuals with some level of secondary education and subsequent formal training of longer duration in a recognised training institution; and level 1 paraprofessionals, who are individuals with some level of secondary education who subsequently received informal, short-duration, pre-service training. The third and lowest level of competency among CHWs includes lay health workers with little or no formal education but who have received informal job-related training.

In addition, we noted that those CHWs who could be classified as lay health workers are usually unpaid volunteers or receive an allowance while those that match the definition of level 1 paraprofessionals often receive an allowance or incentive and the level 2 paraprofessionals are usually salaried. Figure 2 illustrates how the characteristics of educational qualification, pre-service training, and remuneration of the different levels are linked with the different categories of CHWs. It shows that the likelihood of having a salary increases with higher educational qualifications and longer duration of formal pre-service training.

Figure 2.

Linking pre-service training and remuneration to different levels of CHWs.

In line with our review findings, the selection criteria and expected competencies of health workers often vary with the organisations/institutions involved in the selection [138]. These selection criteria will be crucial in identifying fit-for-purpose CHWs, especially as key stakeholders in global health continue to emphasise the advantages of a skills mix in health teams delivering primary care in areas with a health workforce shortage [1]. A clear understanding of the various levels of competencies of CHWs will guide programme planners in identifying and assigning roles to CHWs within the health system. Furthermore, a clear understanding of their competency levels and roles can inform policy and planning of CHW remuneration and career development [139].

CHWs’ service recipients

Evidence shows that CHWs can increase health service coverage to hard-to-reach populations irrespective of country income status [140]. Our review noted that CHWs providing services in high-income settings mostly delivered services related to non-communicable diseases and mainly to hard-to-reach populations. Conversely, CHWs in low- and middle-income countries focus extensively on communicable diseases and maternal and child health and have relatively insignificant roles in the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. There are indications that with appropriate health system support, CHWs can also contribute to the prevention and control of non-communicable disease [141] in low- and middle-income settings where about three-quarters of non-communicable disease-related deaths occur [142].

Similarities and differences with definitions of similar cadres of health workers

The absence of distinct definitions for groups of health workers impairs planning and policy formulation for multidisciplinary health teams [143]. If we compare the common themes in definitions of CHWs with definitions of similar cadres of health workers, it is possible to determine the boundaries between each and make distinctions. Other relevant cadres of health workers include mid-level health workers [144] and Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) [145]. Hence, distinct CHW definition and categories may be key to assigning roles and positions to CHWs in multidisciplinary health teams.

Mid-level health workers are defined as frontline health workers with up to 3 years’ post-secondary school training to perform specific health-related tasks such as clinical or diagnostic functions, which are otherwise conducted by health professionals with a higher educational qualification [146,147]. This is similar to our findings which refer to CHWs as frontline health workers providing information and performing health-related tasks. The main difference is that CHWs receive training of fewer than 3 years. Additionally, our review shows that the primary goal of the CHW is to provide culturally appropriate health services to the community members.

TBAs have been described as individuals who assist mothers during childbirth and have acquired skills by conducting deliveries of babies on their own or through apprenticeship training received from other TBAs [145]. This definition of TBAs contrasts with our findings which suggest that CHWs have received a standardised job-related training in the context of the role they are expected to perform. However, trained TBAs who have received standardised job-related training in the context of an intervention could theoretically be considered as lay health workers but not paraprofessionals as they usually lack secondary education.

Strengths and limitations

Due to resource and time limitations, we only included papers published in English and missed opportunities to review definitions of CHWs included in papers published in other languages (e.g. studies from francophone West Africa or Latin America). We included definitions of CHWs published from 2004–2016, excluding those pre-dating this period such as the definition proposed by the WHO Study Group in 1989:

Community health workers should be members of the communities where they work, should be selected by the communities, should be answerable to the communities for their activities, should be supported by the health system but not necessarily a part of its organization, and have shorter training than professional workers. [148]

We anticipate that we may have missed some definitions that still have contemporary relevance. However, we tried to make up for this by comparing common themes in the definitions included with those within definitions of CHWs pre-dating 2004 and found no diverging or alternative themes.

We acknowledge that our limited literature review to identify and include all alternative terms of CHWs may have missed some relevant terms. Overall, we used 66 alternative terms in this review and they were drawn from different contexts spanning the various socio-economic status and geographical regions; we, therefore, consider that this should be adequate to draw the needed inferences.

We did not assess the quality of papers included in this review because most were not primary research. None of the definitions contained in the included studies were based on any systematic or conceptual framework. To the best of our knowledge, our review is the first to use a methodical approach in defining ‘who is a CHW?’

Conclusions

This review provides a methodical definition of CHWs based on common themes in CHW definitions, thereby clarifying use of the term for health policy makers, programme planners, and researchers. We acknowledge that a single definition may not project the diversity of the group nor is a universal definition desirable given that the concept of CHWs is highly political and has evolved to suit specific contexts, norms, and cultures. However, our review shows a link between pre-service training and remuneration and different levels of CHWs and this is helpful in distinguishing between CHWs as lay health workers or as paraprofessionals. In order to differentiate CHWs from other similar cadres of health workers, definitions of CHWs should emphasise that they are individuals with an in-depth understanding of the community culture and language, have received standardised job-related training which is of shorter duration than health professionals, and their primary goal is to provide culturally appropriate health services to the community.

Recommendations for research and policy

There is a need for further research on sustainable fit-for-purpose models of remunerating lay health workers who are largely unpaid or receive short-term allowances from NGOs. These models may draw on existing models of remunerating levels 1 and 2 paraprofessional CHWs without compromising lay health workers’ accountability and commitment to the community. We, therefore, recommend that the models should reward high performance without compromising intrinsic motivating factors, teamwork, and commitment to the community. Fit-for-purpose and sustainable remuneration models may be key to long-term job satisfaction, commitment, and retention of CHWs, especially considering the resources invested in selecting, training, and equipping them before they start providing services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Caroline Hercod for her assistance with retrieving papers that were not available in the searched databases and for editing the final manuscript.

Biography

AO, RU, and NvdB contributed to the review design. AO and RU independently screened titles and abstracts and the full text for included papers. All authors were involved in the analysis of the data. AO prepared the initial draft of the manuscript and HS, RU, SB, and NvdB provided review comments. The final draft of the manuscript was prepared by AO, HS, and NvdB. All authors approved the final draft of the manuscript.

RESPONSIBLE EDITOR John Kinsman, Umeå University, Sweden

Funding Statement

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article. This work is part of the lead author’s PhD and no external funding was received.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethics and consent

Ethical approval and patient consent were not necessary for this literature review.

Supplemental

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Paper context

Community health worker (CHW) definitions and categories are nuanced differently within and across contexts and stakeholder groups. Our review utilised a methodical approach in identifying the common themes in the various CHW definitions and subsequently developed a competency-based definition and categories that accommodate the peculiarities of the various contexts. This categorisation may inform a common understanding within and across stakeholder groups and also guide community health policy making, programme planning, and research across contexts.

References

- World Health Organization and Global Health Workforce Alliance Synthesis paper of the thematic working groups - health work force 2030 - towards a global strategy on human resources for health. 2015

- World Health Organization Working together for health: the World Health Report 2006. 2006

- Global Health Workforce Alliance Global health workforce crisis key messages - 2013. 2013

- Lewin SA, Dick J, Pond P. Lay health workers in primary and community health care. [cited 2014 Dec 15;];Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 1:CD004015. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub2. Jan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann U, Sanders D. Community health workers: what do we know about them? The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. May 3, cited. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- South J, Meah A, Bagnall A. Dimensions of lay health worker programmes: results of a scoping study and production of a descriptive framework. [cited 2014 Sep 16;];Glob Health Promot. 2013 20:5–13. doi: 10.1177/1757975912464248. Mar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MJ, Squires AP, Bixby RA. Role development of community health workers: an examination of selection and training processes in the intervention literature. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:1. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO UNESCO GUIDELINES for the recognition, validation and accreditation of the outcomes of non-formal and informal learning. 2012

- Perry H, Crigler L, Hodgins S. Developing and strengthening community health worker programs at scale: a reference guide and case studies for program managers and policymakers. 2014

- Benton DC. Technical working group consultation papers 1 to 8: submission to the public consultation process on the global strategy on HRH. 2014 Feb 2; cited. 2016.

- World Health Organization Classifying health workers: mapping occupations to the international standard classification. 2010

- Joint Learning Initiative human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. 2004 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17482-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ryan R. Cochrane consumers and communication review group: data synthesis and analysis. Cochrane Consum Commun Rev Gr. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . Country and lending groups. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2016. Nov 19, cited. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Farah FN, Mohan R, Varadharajan KS. Assessment of “Accredited Social Health Activists” - a national community health volunteer scheme in Karnataka State, India. J Heal Popul Nutr. 2015;33:137–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston R, Acharya B, Poudel D. Early initiation of community-based programmes in Nepal: a historic reflection. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2012;10:82–87. http://nfhp.jsi.com/Docs/EarlyInitiationofCommunity-based ProgrammesinNepal-Ahistoricreflection.pdf Available from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmento RD. Traditional Birth Attendance (TBA) in a health system: what are the roles, benefits and challenges: a case study of incorporated TBA in Timor-Leste. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s12930-014-0012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobezayehu AG, Mohammed H, Dynes MM. Knowledge and skills retention among frontline health workers: community maternal and newborn health training in rural Ethiopia. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2014;59:S21–S31. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowitt SD, Emmerling D, Fisher EB. Community health workers as agents of health promotion: analyzing Thailand’s village health volunteer program. J Community Health. 2015;40:780–788. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-9999-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis L, Termini N. Community health workers for maternal and child health. Population Council Fact Sheet. 2012

- Allen JD, Pérez JE, Tom L. A pilot test of a church-based intervention to promote multiple cancer-screening behaviors among latinas. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:136–143. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0560-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshabela M, Sips I, Barten F. Needs assessment for home-based care and the strengthening of social support networks: the role of community care workers in rural South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:29265. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.29265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabitova G, Burke NJ. Improving healthcare empowerment through breast cancer patient navigation: a mixed methods evaluation in a safety-net setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:407. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Cruz II, Freund KM, Battaglia TA. Impact of depression on the intensity of patient navigation for women with abnormal cancer screenings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25:383–395. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey K, Hingora A, Kante M. The Tanzania connect project: a cluster-randomized trial of the child survival impact of adding paid community health workers to an existing facility-focused health system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:S6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-S2-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynes M, Buffington ST, Carpenter M. Strengthening maternal and newborn health in rural Ethiopia: early results from frontline health worker community maternal and newborn health training. Midwifery. 2013;29:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangham-Jefferies L, Mathewos B, Russell J. How do health extension workers in Ethiopia allocate their time? Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:61. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condo J, Mugeni C, Naughton B. Rwanda’s evolving community health worker system: a qualitative assessment of client and provider perspectives. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:71. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva R, Amouzou A, Munos M. Can community health workers report accurately on births and deaths? Results of field assessments in Ethiopia, Malawi and Mali. Plos One. 2016;11:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal PK, Agrawal S, Ahmed S. Effect of knowledge of community health workers on essential newborn health care: a study from rural India. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:115–126. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams-Gessel SSM, Denman CA, Montano CM. The training and field work experiences of community health workers conducting non-invasive, population-based screening for cardiovascular disease in four communities in low and middle-income settings. Glob Heart. 2015;10:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumtaz Z, Levay A, Bhatti A. Good on paper: the gap between programme theory and real-world context in Pakistan’s community midwife programme. BJOG. 2015;122:249–258. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye CJ, Williams JE, Evatt JH. Improving hypertension self-management with community health coaches. Health Promot Pract. 2015;16:271–281. doi: 10.1177/1524839914533797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D, Cumming R, Negin J. Acceptability and trust of community health workers offering maternal and newborn health education in rural Uganda. Health Educ Res. 2015;30:947–956. doi: 10.1093/her/cyv045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das VNR, Pandey RN, Pandey K. Impact of ASHA training on active case detection of visceral leishmaniasis in Bihar, India. Plos Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran NT, Portela A, De Bernis L. Developing capacities of community health workers in sexual and reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health: a mapping and review of training resources. Plos One. 2014;9:4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikander S, Lazarus A, Bangash O. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the peer-delivered thinking healthy programme for perinatal depression in Pakistan and India: the SHARE study protocol for randomised controlled trials. Trials. 2015;16:534. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1063-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulu JM, Kinsman J, Michelo C. Developing the national community health assistant strategy in Zambia: a policy analysis. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:24. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-11-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulu JM, Kinsman J, Michelo C. Hope and despair: community health assistants’ experiences of working in a rural district in Zambia. Hum Resour Health [Internet] 2014;12:30. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane D, Nielsen C, Dower C. The community health advisor program and the deep south network for cancer control health promotion programs for volunteer community health advisors. Fam Community Health. 2004;28:20–27. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MY. Community health advisors effectively promote cancer screening. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:14–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus M. The importance of social context in understanding and promoting low-income immigrant women’s health. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20:90–97. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill D, Hock-Long L, Mesure M. Healthy Start Programa Madrina: a promotora home visiting outreach and education program to improve perinatal health among latina pregnant women. Heal Educ. 2009;41:68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Herce ME, Chapman JA, Castro A. A role for community health promoters in tuberculosis control in the state of Chiapas, Mexico. J Community Health. 2010;35:182–189. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanchetta MS, Kolawole Salami B, Perreault M. Scientific and popular health knowledge in the education work of community health agents in Rio de Janeiro shantytowns. Health Educ Res. 2012;27:608–623. doi: 10.1093/her/cys072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzadfar F, Murray CJL, Gakidou E. Effectiveness of diabetes and hypertension management by rural primary health-care workers (Behvarz workers) in Iran: a nationally representative observational study. Lancet. 2012;379:47–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Heer HD, Balcazar HG, Castro FG. A path analysis of a randomized Promotora de Salud CVDPrevention trial among at-risk hispanic adults. Heal Educ Behav. 2012;39:77–86. doi: 10.1177/1090198111408720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whop LJ, Valery PC, Beesley VL. Navigating the cancer journey: a review of patient navigator programs for Indigenous cancer patients. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2012;8:89–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2012.01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom DH, Hessler D, De Vore D. Impact of peer health coaching on glycemic control in low-income patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:137–144. doi: 10.1370/afm.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins T, Aguinaga P, Clinton-Selin C. The maternal infant health outreach worker program in low-income families. J Heal Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:995–1001. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S, Najafizada M, Labonté R. Community health workers of Afghanistan: a qualitative study of a national program. Confl Health. 2014;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarfraz M, Hamid S. Challenges in delivery of skilled maternal care - experiences of community midwives in Pakistan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uriarte JA, Cummings ADL, Lloyd LE. An instructional design model for culturally competent community health worker training. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15:S56–63. doi: 10.1177/1524839913517711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redick C, Dini HSF, Long L-A. The current state of CHW training programs in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia: what we know, what we don’t know, and what we need to do. 2014

- Barogui YT, Sopoh GE, Johnson RC. Contribution of the community health volunteers in the control of Buruli Ulcer in Bénin. Plos Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:0003200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez DE, Reynolds CF, Alegría M. The Happy Older Latinos are Active (HOLA) health promotion and prevention study: study protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:579. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1113-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez D, Ramírez-Andreotta M, Vea L. Pollution prevention through peer education: a community health worker and small and home-based business initiative on the Arizona-Sonora Border. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:11209–11226. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120911209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrington A, Agne A, Lampkin YB. Diabetes connect developing a mobile health intervention to link diabetes community health workers with primary care. J Ambul Care Manage. 2015;38:333–345. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Gunn VL. Community health workers as a component of the health care team. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62:1313–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA, Mueser KT. Community health workers: potential allies for the field of psychiatric rehabilitation? Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38:207–209. doi: 10.1037/prj0000164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbero C, Gilchrist S, Chriqui JF. Do state community health worker laws align with best available evidence ? J Community Health. 2016;41:315–325. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskan A, Friedman DB, Hilfinger Messias DK. Sustainability of promotora initiatives: program planners’ perspectives. J Public Heal Manag Pract. 2013;19:1–15. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318280012a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein JN, Bone LR, Dennison CR. Community health workers as interventionists in the prevention and control of heart disease and stroke. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:S128–S133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association Support for community health workers to increase health access and to reduce health inequities. 2009

- Herman AA. Community health workers and integrated primary health care teams in the 21st century. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34:354–361. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31822cbcd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Ingram M. Community health workers then and now: an overview of national studies aimed at defining the field. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34:247–259. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31821c64d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WestRasmus EK, Pineda-Reyes F, Tamez M. Promotores de salud and community health workers: an annotated bibliography. Fam Community Health. 2012;35:172–182. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31824991d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crigler L, Glenton C, Hodgins S. Developing and strengthening community health worker programs at scale: a reference guide for program managers and policy makers. Baltimore: Jhpiego Corporation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo MF, Walldorf J, Kolesar R. Evaluation of a volunteer community-based health worker program for providing contraceptive services in Madagascar. Contraception. 2013;88:657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar HG, Wise S, Redelfs A. Perceptions of Community Health Workers (CHWs/PS) in the U.S.-Mexico Border HEART CVD study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:1873–1884. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110201873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes S, Cabral A, De Sousa B. Community health workers: to train or to restrain? A longitudinal survey to assess the impact of training community health workers in the Bolama Region, Guinea. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelkar S, Mahapatro M. Community health worker: a tool for community empowerment. Heal Popul Perspect Issues. 2014;37:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton A, Downey J, Lisovicz N. The community health advisor program and the deep South network for cancer control: health promotion programs for volunteer community health advisors. Fam Community Health. 2005;28:20–27. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granillo B, Renger R, Wakelee J. Utilization of the native American talking circle to teach incident command system to tribal community health representatives. J Community Health. 2010;35:625–634. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock N, Michele Issel L, Townsell SJ. An innovative method to involve community health workers as partners in evaluation research. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:2275–2280. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Litaker MS, Scarinci IC. Spiritually based intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among African Americans: screening and theory-based outcomes from a randomized trial. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40:458–468. doi: 10.1177/1090198112459651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Ko N, Battaglia TA. Patient navigation for underserved patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Oncologist. 2012;17:1027–1031. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Association . Community health workers national workforce study. Washington (DC): Health Resources and Services Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy LA, Milton B, Bundred P. Lay food and health worker involvement in community nutrition and dietetics in England: definitions from the field. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2008;21:196–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2008.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas RB, Ryan GW, Jackson CA. Characteristics of the original patient navigation programs to reduce disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:426–433. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmstadt GL, Lee ACC, Cousens S. 60 million non-facility births: who can deliver in community settings to reduce intrapartum-related deaths? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107:S89–S112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvillar M, Quinlan J, Rush CH. Recommendations for developing and sustaining community health workers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22:745–750. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto R, Flynn S, Jorge F. Lay health educator role in improving cancer screening rates in underserved communities. Health. 2014;6:328–335. [Google Scholar]

- Trejo G, Arcury TA, Grzywacz JG. Barriers and facilitators for promotoras’ success in delivering pesticide safety education to latino farmworker families: La Familia Sana. J Agromedicine. 2013;18:75–86. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2013.766143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkey LK, Herman PM, Roe DJ. A cancer screening intervention for underserved Latina women by lay educators. J Womens Health. 2012;21:557–566. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskan AM, Friedman DB, Brandt HM. Preparing promotoras to deliver health programs for hispanic communities: training processes and curricula. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14:390–399. doi: 10.1177/1524839912457176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalani CE, Findley SE, Matos S. Community health worker insights on their training and certification. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2009;3:227–235. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla ZE, Morrison SD, Norsigian J. Reaching latinas with our bodies, ourselves and the Guıa de Capacitacion para Promotoras de Salud: health education for social change. J Midwifery Women’s Heal. 2012;57:178–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi S, Schneider H. Addressing the social determinants of health: a case study from the Mitanin (community health worker) programme in India. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:ii71–ii81. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating N, Kouri EM, Arreola O. Evaluation of breast cancer knowledge among health promoters in Mexico before and after focused training. Oncologist. 2014;19:1091–1099. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha BP, Bhandari B, Manandhar DS. Community interventions to reduce child mortality in Dhanusha, Nepal: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12:136. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin E, Lunsford SS, Sooden A. The mixed nature of incentives for community health workers: lessons from a qualitative study in two districts in India. Front Public Heal. 2016;4:38. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulu JM, Hurtig A-K, Kinsman J. Innovation in health service delivery: integrating community health assistants into the health system at district level in Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:38. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0696-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prata N, Gessessew A, Cartwright A. Provision of injectable contraceptives in Ethiopia through community-based reproductive health agents. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:556–564. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.086710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) - the trained woman community health volunteer. Nurs J India. 2005;96:252–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Briggs F. Training community health workers as diabetes educators for urban African Americans: value added using participatory method. Prog Community Heal Partnersh. 2007;1:185–194. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau Y, Buettner P, Usher K. Burden experienced by community health volunteers in Taiwan: a survey. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:491. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peu MD. Health promotion strategies for families with adolescents orphaned by HIV and AIDS. Int Nurs Rev. 2014;61:228–237. doi: 10.1111/inr.12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Give CS, Sidat M, Ormel H. Exploring competing experiences and expectations of the revitalized community health worker programme in Mozambique: an equity analysis. Hum Resour Health Human Resources Health. 2015;13:54. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0044-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wholey DR, White KM, Adair R. Care guides: an examination of occupational conflict and role relationships in primary care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2013;38:272–283. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31825f3df9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne N, Ritvo P. Smartphone-enabled health coach intervention for people with diabetes from a modest socioeconomic strata community: single-arm longitudinal feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:149. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimoli JF, Frymus DE, Quain EE. Community and formal health system support for enhanced community health worker performance: a US government evidence summit. Washington (DC): USAID; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Sachs JD, Sachs D. 1 million community health workers in sub-Saharan Africa by 2015. Lancet. 2013;382:363–365. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frontline Health Workers Coalition . A commitment to community health workers: improving data for decision-making. Washington (DC): Frontline Health Workers Coalition; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Filgueiras AS, Silva ALA. Agente Comunitário de Saúde: Um novo ator no cenário da saúde do Brasil [Community Health Agent: a new actor in the Brazilian health scenario] Physis. 2011;21:899–915. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N, Trojanowski L, Dewa CS. What do peer support workers do? A job description. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:205. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver H, Douglas MJ, Tomlinson JEM. The outreach worker role in an anticipatory care programme: a valuable resource for linking and supporting. Public Health. 2012;126:S47–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann LJ, Buck Richardson WJ, Floyd J. Tribal Veterans Representative (TVR) training program: the effect of community outreach workers on American Indian and Alaska native veterans access to and utilization of the veterans health administration. J Community Health. 2014;39:990–996. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9846-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jandorf L, Gutierrez Y, Lopez J. Use of a patient navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban neighborhood health clinic. J Urban Heal. 2005;82:216–224. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petereit DG, Molloy K, Reiner ML. Establishing a patient navigator program to reduce cancer disparities in the American Indian communities of Western South Dakota: initial observations and results. Cancer Control. 2008;15:254–259. doi: 10.1177/107327480801500309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparza A, Calhoun E. Measuring the impact and potential of patient navigation: proposed common metrics and beyond. Cancer. 2011;117:3537–3538. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Walleghem N, MacDonald CA, Dean HJ. The Maestro project: a patient navigator for the transition of care for youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2011;24:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pierre PJ, Fiscella K, Winters PC. Psychometric development and reliability analysis of a patient satisfaction with interpersonal relationship with navigator measure: a multisite patient navigation research program study. Psychooncology. 2012;21:986–992. doi: 10.1002/pon.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff SL, Pekow PS, White KO. IDEAS for a healthy baby - reducing disparities in use of publicly reported quality data: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:244. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruben K, Mortensen K, Eldridge B. Emergency department referral process and subsequent use of safety-net clinics. J Immigr Minor Heal. 2015;17:1298–1304. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0111-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranaghan CP, Boyle K, Fraser P. The effectiveness of therapeutic patient education on adherence to oral anti-cancer medicines in adult cancer patients in ambulatory care settings: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13:54–69. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlot M, Santana MC, Chen CA. Impact of patient and navigator race and language concordance on care after cancer screening abnormalities. Cancer. 2015;121:1477–1483. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SM, Cervantes L, Fink RM. Apoyo Con Carino: a pilot randomized control trial of a patient navigator intervention to improve palliative care outcomes for Latinos with serious illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner AT, Getrich CM, Pignone M. Comparing the effect of a decision aid plus patient navigation with usual care on colorectal cancer screening completion in vulnerable populations: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:275. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber BS, Rapacki L, Castillo A. Design of a trial to evaluate the impact of clinical pharmacists and community health promoters working with African-Americans and Latinos with diabetes. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:891. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash RJ, Rhode H, Zwarenstein M. Educational and psychological issues effectiveness of a group diabetes education programme in under-served communities in South Africa: a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2014;31:987–994. doi: 10.1111/dme.12475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benskin LLL, Concept A. Development of the village health worker. Nurs Forum. 2012;47:173–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2012.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkin EB, Shapiro E, Snow JG. The economic impact of a patient navigator program to increase screening colonoscopy. Cancer. 2012;118:5982–5988. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael JL, Rueda A, Lion KC. The role of lay health workers in pediatric chronic disease: a systematic review. Acad Paediatr. 2013;13:408–421. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston HB, Ganatra B, Nguyen MH. Accuracy of assessment of eligibility for early medical abortion by community health workers in Ethiopia, India and South Africa. Plos One. 2016;11:0146305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkwo PO, Lawani LO, Ubesie AC. Poor availability of skilled birth attendants in Nigeria: a case study of enugu state primary health care system. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2015;5:20–25. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.149778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douthwaite M, Ward P. Increasing contraceptive in rural Pakistan: an evaluation of the lady health worker programme. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20:117–123. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawaa E, Kodamab T, Kundishorac E. Motivation and sustainability of care facilitators engaged in a community home-based HIV/AIDS program in Masvingo Province, Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2010;22:895–902. doi: 10.1080/09540120903499196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti M, Bowleg L, Spencer SB. Who helps the helpers? A clinical supervision strategy to support peers and health educators who deliver sexual risk reduction interventions to women living with HIV/AIDS. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2009;8:430–446. [Google Scholar]

- Haq Z, Iqbal Z, Rahman A. Job stress among community health workers: a multi-method study from Pakistan. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2008;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Deveridge A, Berman J. Task-shifting and prioritization: a situational analysis examining the role and experiences of community health workers in Malawi. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:24. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A, Young M, Nefdt R. Community health workers providing government community case management for child survival in sub-Saharan Africa: who are they and what are they expected to do? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:S85–91. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasanathan K, Muniz M, Bakshi S. Community case management of childhood illness in sub-Saharan Africa: findings from cross-sectional survey on policy and implementation. J Glob Health. 2014;4:020401. doi: 10.7189/jogh.04.020401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, WB, USAID . Handbook on monitoring and evaluation of human resources for health: with special applications for low- and middle-income countries [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lawler EE. From job-based to competency-based organizations. Los Angeles: Center for Effective Organizations; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Freund T, Everett C, Griffiths P. Skill mix, roles and remuneration in the primary care workforce: who are the healthcare professionals in the primary care teams across the world? Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:727–743. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Office . International standard classification of occupations: structure, group definitions and correspondence tables. Geneva: Internet Labour Office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R. Employers expectations of core functions, credentials and competencies of the community and public health nutrition workforce in Australia. Nutr Diet. 2004;61:105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne J, Hirsh W, Williams S. The development of management and leadership capability and its contribution to performance: the evidence, the prospects and the research need. London: Department for Education and Skills; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:399–420. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra SR, Neupane D, Preen D. Mitigation of non-communicable diseases in developing countries with community health workers. Global Health. 2015;11:43. doi: 10.1186/s12992-015-0129-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, World Bank, USAID . Handbook on monitoring and evaluation of human resources for health: with special applications for low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann U. Mid-level health workers. The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes: a literature review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley L, Sipe TA, Barry D. Traditional birth attendant training for improving health behaviours and pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD005460. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005460.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovlo D. Using mid-level cadres as substitutes for internationally mobile health professionals in Africa. A desk review. Hum Resour Health. 2004;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Health Workforce Alliance . Mid-level health workers for delivery of essential health services: a global systematic review and country experiences. Geneva: Global Health Workforce Alliance; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Strengthening the performance of community health workers in primary health care [Internet] 1989 [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.