ABSTRACT

Embedded in the colonic mucus are cathelicidins, small cationic peptides secreted by colonic epithelial cells. Humans and mice have one cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide (CRAMP) each, LL-37/hCAP-18 and Cramp, respectively, with related structure and functions. Altered production of MUC2 mucin and antimicrobial peptides is characteristic of intestinal amebiasis. The interactions between MUC2 mucin and cathelicidins in conferring innate immunity against Entamoeba histolytica are not well characterized. In this study, we quantified whether MUC2 expression and release could regulate the expression and secretion of cathelicidin LL-37 in colonic epithelial cells and in the colon. The synthesis of LL-37 was enhanced with butyrate (a product of bacterial fermentation) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (a proinflammatory cytokine in colitis) in the presence of exogenously added purified MUC2. The LL-37 responses to butyrate and IL-1β were higher in high-MUC2-producing cells than in lentivirus short hairpin RNA (shRNA) MUC2-silenced cells. Activation of cyclic adenylyl cyclase (AMP) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways was necessary for the simultaneous expression of MUC2 and cathelicidins. In Muc2 mucin-deficient (Muc2−/−) mice, murine cathelicidin (Cramp) was significantly reduced compared to that in Muc2+/− and Muc2+/+ littermates. E. histolytica-induced acute inflammation in colonic loops stimulated high levels of cathelicidin in Muc2+/+ but not in Muc2−/− littermates. In dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis in Muc2+/+ mice, which depletes the mucus barrier and goblet cell mucin, Cramp expression was significantly enhanced during restitution. These studies demonstrate regulatory mechanisms between MUC2 and cathelicidins in the colonic mucosa where an intact mucus barrier is essential for expression and secretion of cathelicidins in response to E. histolytica- and DSS-induced colitis.

KEYWORDS: Entamoeba histolytica, MUC2, antimicrobial peptides, mucin

INTRODUCTION

The innate defenses of the colon and first barrier against pathogens include glycosylated MUC2 mucin secreted by goblet cells that forms an inner sterile layer firmly attached to the epithelium and an outer layer with an expanded volume and that is colonized by bacteria (1). Embedded in colonic mucus are cathelicidins, small cationic peptides (23 to 37 amino acids) secreted by neutrophils and epithelial cells, including colonic epithelium, with broad antimicrobial activity (2, 3). The only cathelicidin described in humans is LL-37/hCAP-18, which is homologous to mouse cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide (CRAMP) (2, 3). Both LL-37 and CRAMP have related structure and antimicrobial and chemotactic functions (2, 3). Sodium butyrate produced by commensal bacteria in the colon functions as a histone deacetylase inhibitor to induce cathelicidin mRNA and protein expression in the colonic epithelium (4).

The intestinal mucus barrier is critical in innate host defense against protozoan infections. Infectious colitis caused by Entamoeba histolytica, a protozoan that causes amebic dysentery and/or liver abscesses (5), is a good model to study the relevance of innate factors in the colon in response to an enteric pathogen. The virulence factor cysteine proteinase 5 of E. histolytica (EhCP5) is a potent mucus secretagogue (6) that can also dissolve the mucus barrier by degrading MUC2 (7–9). In contact with the gut mucosa, EhCP5 binds macrophages/dendritic cells to evoke a potent proinflammatory response dominated by interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (10, 11). In Muc2−/− mice, E. histolytica inoculated in colonic loops elicited robust secretory and acute proinflammatory responses, aberrant protein secretions, and altered tight junction permeability (12). Prolonged contact of E. histolytica with the colonic epithelium induced the synthesis of cathelicidins in humans and mouse, which were degraded by E. histolytica cysteine proteinases (13). Even though E. histolytica is resistant to killing by LL-37 (13), one report showed that shortened peptides derived from cleaved LL-37 affected E. histolytica integrity and viability (14). Altered production of colonic mucin and antimicrobial peptides is also characteristic of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs). In ulcerative colitis (UC), the thickness of the adherent mucus gel is reduced, even to the point of denudation, in areas with acute inflammation (15, 16) and the number of mature goblet cells is decreased in the upper third of the crypts (17). In UC, the expression of cathelicidin is increased, mostly in the inflamed mucosa (18). Likewise, colitis induced by dextran sodium sulfate (DSS), an animal model that mimics human UC, downregulates Muc2 mucin genes with depletion of goblet cells and adherent mucin in rats (19), while it increases CRAMP protein expression in the colonic epithelium and macrophages in mice (20). In Crohn's disease, the mucin layer appears normal or even thicker than that in controls (15, 16) with no increase in the expression of cathelicidin (18).

These studies indicate that the innate immune factors MUC2 mucin and cathelicidins may act in concert at the colonic mucosa to support the microbiota and to prevent entry of pathogens. In support of this, we have recently established that defective colonic MUC2 mucin leads to deficient stimulation of β-defensin 2 produced by the colonic epithelium (21). In the present study, we interrogated the innate host defense mechanisms at the colonic mucosa by determining the cooperative or regulatory expression of MUC2 mucin and cathelicidins under homeostatic conditions and in response to E. histolytica-induced inflammation and chronic colitis induced by dextran sodium sulfate (DSS). Our results demonstrate that MUC2 gene expression and mucus release and butyrate were necessary for the expression and secretion of cathelicidin in human cultured colonic epithelial cells. Moreover, in the absence of the colonic mucus barrier or in its altered state, there was an impaired local cathelicidin response toward E. histolytica and DSS-induced colitis in mice.

RESULTS

Butyrate and MUC2 mucin regulate the expression and production of cathelicidin LL-37 peptide in human colonic epithelial cells.

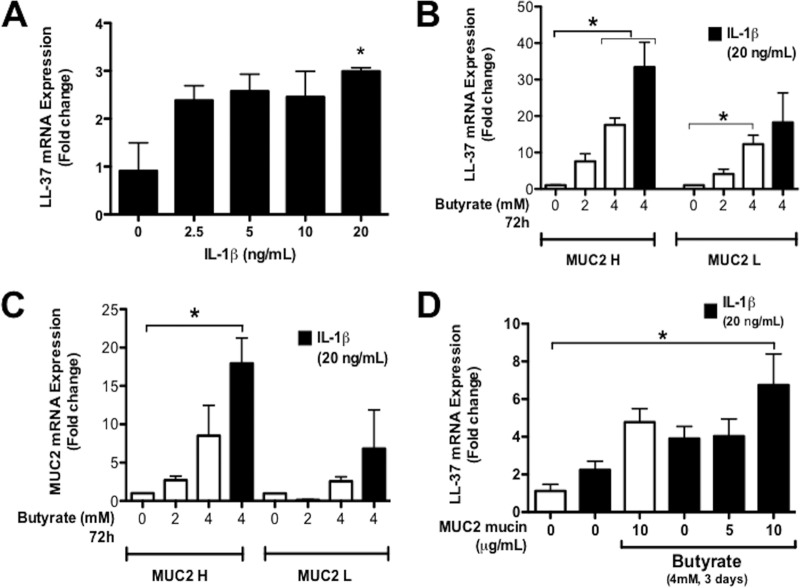

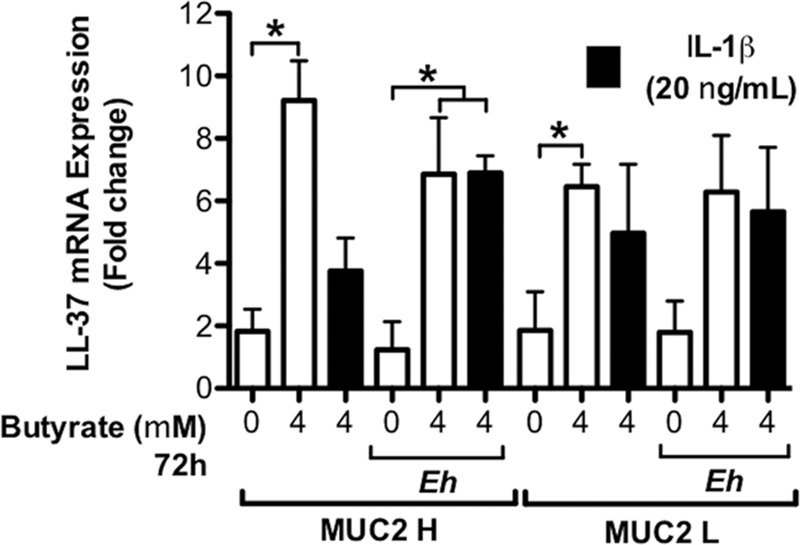

Previous studies have shown that parental HT-29 cells pretreated with butyrate promoted the synthesis of cathelicidins (4, 22) and MUC2 (23). We used these cells to investigate the effect of IL-1β, a hallmark proinflammatory cytokine observed in amebic colitis (11) and IBD (24), in the synthesis of cathelicidins in the presence/absence of butyrate and MUC2 mucin. When parental HT-29 cells were stimulated with graded doses of IL-1β, there was a modest increase in LL-37 expression only with the highest concentration used (20 ng/ml) (Fig. 1A). Thus, to determine whether the high-MUC2 mucin phenotype was necessary for the expression of cathelicidin under inflammatory conditions, we next determined if this concentration of IL-1β promoted a differential cathelicidin response in MUC2 H/L cells. To do this, MUC2 H/L cells were first stimulated with graded doses of butyrate alone that significantly induced LL-37 gene expression (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1B). MUC2 H/L cells primed with butyrate were then stimulated with IL-1β (20 ng/ml). Under these conditions, IL-1β induced a 10-fold increase in LL-37 mRNA expression over that with butyrate induction alone in MUC2 H but not MUC2 L cells (Fig. 1B). Increasing doses of butyrate (0 to 4 mM; 72 h) induced a modest stepwise increase in MUC2 mRNA expression in MUC2 H/L cells (Fig. 1C). However, in the presence of butyrate, IL-1β enhanced MUC2 gene expression 8-fold in MUC2 H cells (Fig. 1C). Neither butyrate nor IL-1β alone or in combination had a significant effect on MUC2 gene expression in MUC2 L cells.

FIG 1.

Cathelicidin expression in human colonic epithelial cells. (A) The expression of LL-37 mRNA was quantified in parental HT-29 cells pretreated with butyrate (4 mM for 2 days) with increasing doses of IL-1β (0 to 20 ng/ml; 16 h). (B and C) Expression of MUC2 and cathelicidin LL-37 mRNA was quantified in MUC2 H and MUC2 L cells. (D) Expression of LL-37 mRNA in parental HT-29 cells supplemented with purified human colonic MUC2. (B to D) Colonic cells were pretreated with butyrate and then stimulated with IL-1β (20 ng/ml; 16 h). MUC2 and LL-37 mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR and expressed as fold change relative to untreated cells. P values for all significant comparisons with control group are represented (*, P < 0.05).

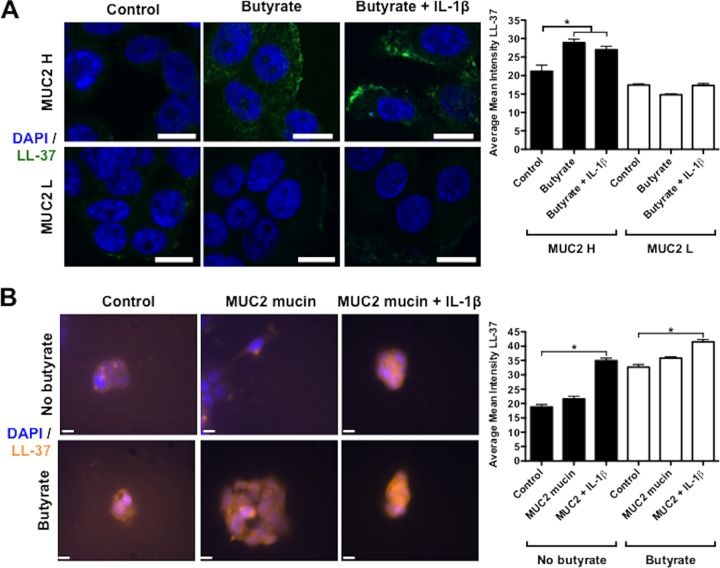

As LL-37 responses to inflammatory stimulus were more prominent in the presence of butyrate and MUC2, we next determined if exogenously added MUC2 mucin could promote cathelicidin synthesis in parental HT-29 cells. HT-29 cells primed with butyrate and then supplemented with increasing doses of exogenous purified MUC2 showed increased LL-37 gene expression in the presence of IL-1β (Fig. 1D). Immunofluorescence studies showed that prestimulation with butyrate (4 mM; 72 h) followed by IL-1β (20 ng/ml; 16 h) induced strong immunoreactive LL-37 peptide in the cytoplasm of MUC2 H cells with punctate accumulation at the periphery of the cells (Fig. 2A). Butyrate alone induced expression of LL-37 peptide diffused throughout the cytoplasm in MUC2 H cells (Fig. 2A). The accumulation of LL-37 after stimulation with butyrate or IL-1β was observed to a lesser extent in MUC2 L cells (Fig. 2A). Likewise, confocal studies in parental HT-29 cells showed that butyrate and MUC2 mucin induced the accumulation of intracellular cathelicidin LL-37 exposed to IL-1β (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these data show that both butyrate and MUC2 mucin mRNA expression and biosynthesis of mature mucin were critical for the induction and synthesis of cathelicidins in colonic epithelial cells. Moreover, cathelicidin expression was augmented in an inflammatory milieu characterized here by the presence of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β.

FIG 2.

Intracellular localization of cathelicidin is increased in human colonic epithelial cells stimulated by butyrate and MUC2 mucin. (A) Cathelicidin LL-37 was detected with primary mouse monoclonal antibody anti-LL-37 (green) in HT-29 MUC2 H/L cells. Cells were prestimulated with butyrate (4 μM; 72 h) and then stimulated with IL-1β (20 ng/ml; 16 h). (B) Cathelicidin LL-37 was detected with primary mouse monoclonal antibody anti-LL-37 (yellow) in parental HT-29 cells prestimulated with butyrate (4 μM; 72 h) and then stimulated with purified MUC2 mucin (10 μg/ml) and IL-1β (20 ng/ml) for 16 h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). IgG was used as antibody control. Image is from 1 of 5 independent experiments. Bars, 10 μm. *, P < 0.05. Quantification of confocal images was performed by measuring the intensity of LL-37 immunostaining within the cell and represented in the contiguous histograms.

Activation of cAMP and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways is necessary for the simultaneous expression of MUC2 and cathelicidins in colonic epithelial cells.

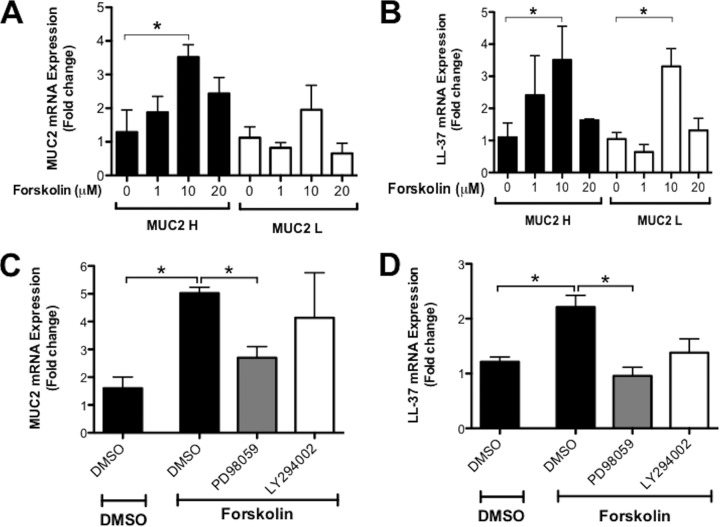

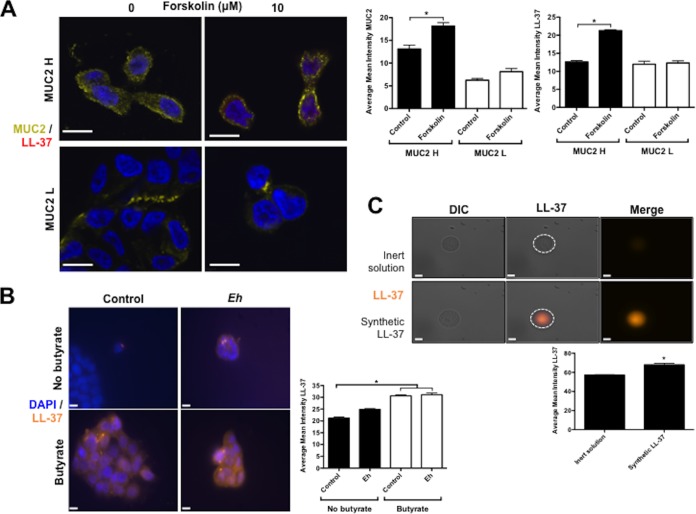

To evaluate common intracellular signaling mechanisms in the regulation of MUC2 and cathelicidins, we focused on the adenylyl cyclase pathway that was shown to transcriptionally regulate cathelicidin (25) and newly synthesized mucin (26) in intestinal epithelial cells. Butyrate activates cyclic AMP (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB) and increases the activity of cAMP response element (CRE) (27), both of which have been implicated in the activation of the cathelicidin promoter (25). Similarly, IL-1β mediates mucin regulation through activation of CREB in epithelial cells (28). Consistently with these findings, we observed that the cAMP agonist forskolin (1 to 20 μM) significantly (P < 0.05) increased MUC2 and LL-37 mRNA expression in MUC2 H cells (Fig. 3A and B). MUC2 L cells also showed the capacity to produce cathelicidins when stimulated with forskolin (Fig. 3B). These findings were confirmed by immunofluorescence studies that showed that forskolin increased intracytoplasmic accumulation of MUC2 mucin and LL-37 peptides in the cytoplasm of MUC2 H cells, although it was not evident in MUC2 L cells (Fig. 4A). To explore the mechanism by which cAMP regulated the induction of MUC2 and cathelicidins, we interrogated two families of downstream signaling proteins, MAPK kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. To do this, MUC2 H/L cells were incubated with specific inhibitors of MAPK kinase (PD98059, 20 μM, 1 h) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (LY294002, 20 μM, 1 h) before incubation with forskolin (10 μM, 3 h) (Fig. 3C and D). Inhibiting MAPK kinase significantly (P < 0.05) reduced cAMP-induced MUC2 and LL-37 mRNA expression (Fig. 3C and D) whereas the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor did not (Fig. 3C and D). These results suggest that the cAMP signaling pathway largely contributed to the expression of both MUC2 and LL-37 genes.

FIG 3.

Forskolin activation of the adenylyl cyclase pathway induces simultaneously MUC2 and cathelicidin mRNA in colonic epithelial cells. MUC2 and cathelicidin LL-37 mRNA was quantified in colonic epithelial cells by qPCR and expressed as fold change relative to unstimulated controls. (A and B) MUC2 H/L cells were stimulated with forskolin (10 μM; 3 h). (C and D) Parental HT-29 cells were incubated with forskolin (10 μM; 3 h) before pretreatment with specific inhibitors of MAPK/ERK kinase (PD98059; 20 μM; 1 h), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors (LY294002; 20 μM; 1 h), or DMSO, the organic solvent used to dissolve the inhibitors, as control. P values for all significant comparison with control group are represented (*, P < 0.05).

FIG 4.

(A) The activator of adenylyl cyclase forskolin induces intracellular localization of MUC2 mucin and LL-37 cathelicidin in human colonic epithelial cells. MUC2 H/L cells were pretreated with butyrate (72 h) and then stimulated with forskolin (10 μM; 3 h). LL-37 was detected with primary mouse monoclonal antibody anti-LL-37 (red), and mucin was detected with primary rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-human LS174T mucin (yellow). (B) Intracellular localization of cathelicidin is increased in human colonic epithelial cells stimulated by butyrate and not by E. histolytica. Cathelicidin LL-37 was detected with primary mouse monoclonal antibody anti LL-37 (orange) in parental HT-29 cells prestimulated with butyrate (4 μM; 72 h) and then stimulated with live E. histolytica trophozoites (1 × 104/ml; 1 h). (C) Cathelicidins bound to E. histolytica trophozoites. Glutaraldehyde-fixed E. histolytica trophozoites (3 × 105) were incubated with synthetic LL-37 (5 μM) for 1 h, and bound LL-37 was detected with primary monoclonal murine IgG antibodies (OSX12; Novus Bio) (yellow). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). IgG was used as antibody control. Image is from 1 of 5 independent experiments. Bar, 10 μm. *, P < 0.05. Quantification of confocal images was performed by measuring the intensity of LL-37 and MUC2 immunostaining within the cell, or bound on the surface of trophozoites, and represented in the contiguous histograms. DIC, differential inference contrast; Eh, E. histolytica.

Butyrate priming enhances cathelicidin expression in response to E. histolytica.

E. histolytica is a model enteric pathogen that degrades components of innate host defenses, including the mucin polymer network and cathelicidins (9, 13), followed by disruption and invasion of the colonic epithelium (7, 12). To evaluate the importance of MUC2 mucin in aiding epithelial cathelicidin defenses against E. histolytica, we evaluated the expression of cathelicidin in butyrate-primed MUC2 H/L cells exposed to IL-1β or E. histolytica trophozoites. Treatment with butyrate (72 h) significantly (P < 0.05) induced LL-37 mRNA expression in MUC2 H cells (Fig. 5) while stimulation with IL-1β (20 ng/ml) following butyrate exposure did not induce a further increase in LL-37 mRNA expression in MUC2 H cells (Fig. 5). The butyrate effect was replicated in cells lacking MUC2 (Fig. 5). Exposure to E. histolytica trophozoites (30 min) did not induce further increases in LL-37 mRNA expression in either MUC2 H or MUC2 L cells beyond the increase induced by butyrate alone in MUC2 H cells (Fig. 5). The importance of butyrate was demonstrated by microscopy studies that showed higher LL-37 immunostaining in colonic cells treated with butyrate (with or without E. histolytica) (Fig. 4B). Moreover, confocal microscopy studies showed synthetic LL-37 bound to the surface of fixed E. histolytica (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that cathelicidin responses in colonic epithelial cells expressing MUC2 mucin are mainly induced by butyrate and that these peptides can bind the membrane of the parasite. Short exposure of colonic epithelial cells to E. histolytica trophozoites did not augment cathelicidin gene expression.

FIG 5.

Butyrate pretreatment enhances the expression of cathelicidins and is increased in response to IL-1β and E. histolytica. The expression of LL-37 mRNA was quantified in MUC2 H/L cells by qPCR and expressed as fold change relative to control MUC2 H cells. Colonic cells (1 × 105/ml) were preincubated with butyrate (4 μM, 72 h) and stimulated with IL-1β (20 ng/ml; 16 h) followed by live E. histolytica trophozoites (1 × 104/ml; 1 h). P values for all significant comparisons with control group are represented (*, P < 0.05). Eh, E. histolytica.

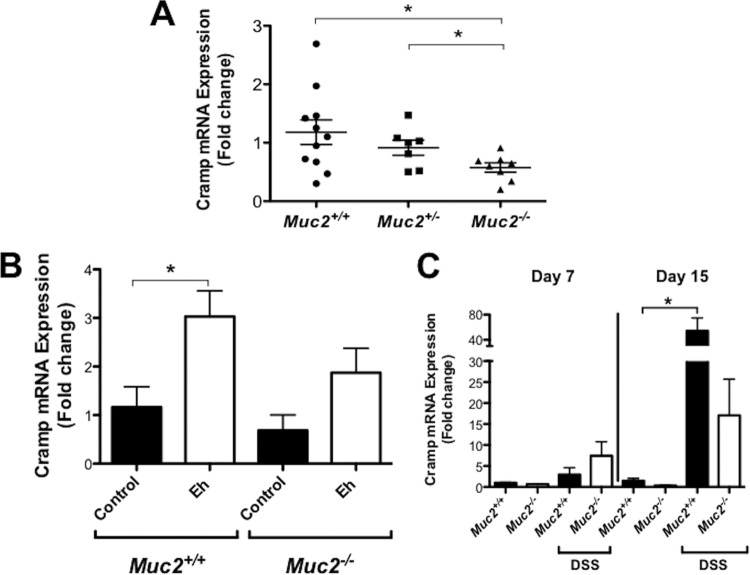

Muc2−/− littermates express reduced cathelicidin in the colon.

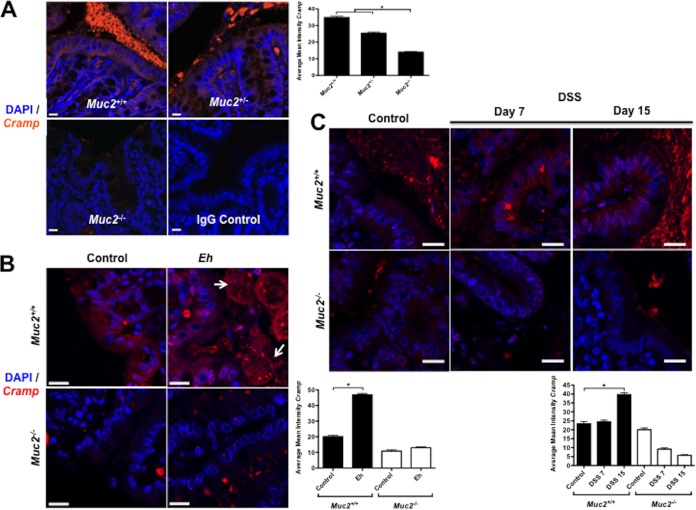

We have recently shown that Muc2−/− mice are deficient in β-defensins in the colon (21). Muc2−/− mice develop low-grade spontaneous colitis that mimics lesions similar to those in UC. To determine if the absence of a mucin barrier or Muc2 biosynthesis could also affect the production of other host defense peptides such as cathelicidin, we quantified the expression of mouse cathelicidin Cramp in Muc2+/+, Muc2+/−, and Muc2−/− littermates. As predicted, Muc2−/− mice showed lower basal expression of Cramp mRNA in the colon than did Muc2+/− and Muc2+/+ littermates (Fig. 6A). By confocal microscopy, Muc2−/− mice showed almost no Cramp immunoreactive peptide in the colonic mucosa compared to Muc2+/− and Muc2+/+ mice, which showed Cramp immunoreactive peptide distributed throughout the cytoplasm in colonic epithelial cells and intense expression in the gut lumen within the mucus layer (Fig. 7A).

FIG 6.

Cathelicidin expression in the colon is impaired in animals deficient in Muc2 and in response to E. histolytica and DSS-induced colitis. Expression of Cramp mRNA was quantified in the colonic mucosa of Muc2+/+, Muc2+/−, and Muc2−/− mice by qPCR and expressed as fold change relative to control Muc2+/+ mice. Mice remained under untreated conditions (A), were challenged with live E. histolytica trophozoites in closed colonic loops for 3 h (B), or were provided DSS in drinking water (3% for five consecutive days for Muc2+/+ mice and 1% for 3 days for Muc2−/− littermates) followed by water and euthanized at days 7 and 15 posttreatment (C). P values for all significant comparisons with control Muc2+/+ group (*, P < 0.05) are represented. Eh, E. histolytica.

FIG 7.

Intracellular localization of murine cathelicidin in the colonic mucosa in response to E. histolytica (Eh) or DSS. (A) Murine cathelicidin was detected with primary rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-Cramp (orange) in untreated Muc2+/+, Muc2+/−, and Muc2−/− littermates. (B) Colonic cathelicidin response to E. histolytica is decreased in Muc2−/− mice. Muc2+/+ and Muc2−/− littermates were challenged with live E. histolytica trophozoites in closed colonic loops for 3 h. (C) Colonic cathelicidin response in dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) colitis is decreased in mice with an impaired mucin barrier. Mice received DSS in drinking water (3% for five consecutive days for Muc2+/+ mice and 1% for 3 days for Muc2−/− mice) and were euthanized at days 7 and 15 posttreatment. Murine cathelicidin was detected with anti-Cramp primary rabbit polyclonal antibody (red) in the colonic mucosa. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Arrows indicate E. histolytica trophozoites in close contact with the epithelium. Image is from 1 of 5 independent experiments. Bar, 15 μm. *, P < 0.05. Quantification of confocal images was performed by measuring the intensity of Cramp immunostaining within the cell and represented in the contiguous histograms.

Even though Cramp is basally expressed, it is not known if its expression could be altered in response to E. histolytica. To study this, we used a murine model of acute inflammation induced by inoculating E. histolytica trophozoites in closed colonic loops (12). We observed that in the absence of mucin in Muc2−/− mice, Cramp mRNA expression was low, whereas in Muc2+/+ littermates, Cramp expression in response to E. histolytica was significantly enhanced compared to that in control loops (Fig. 6B). By immunofluorescence, intense Cramp immunoreactive staining was evident in the colonic epithelium in control and E. histolytica-inoculated colon in Muc2+/+ but not Muc2−/− mice (Fig. 7B). Importantly, cathelicidin peptides appeared as distinct puncta that were bound to E. histolytica trophozoites in close proximity to the colonic epithelium. No dead E. histolytica cells were observed that contacted and/or ingested the cathelicidin peptides. In Muc2−/− mice, E. histolytica was not observed close to the epithelial surface (Fig. 7B) and colonic loops had intense fluid-filled exudates. These results suggest that an intact Muc2 mucin barrier was necessary for the colonic epithelium to produce and secrete cathelicidins basally and in response to E. histolytica infection.

The role of cathelicidins in the intestine is restricted not only to acute amebic colitis, as cathelicidins have been shown to ameliorate chronic DSS-induced colitis (20, 29). However, at present, it is not known if the cathelicidin response observed in amebic colitis is comparable to that in chronic colitis producing an altered mucus barrier. This mechanism is of importance to understand cathelicidin defenses against E. histolytica, as the mucus barrier is degraded by E. histolytica followed by depletion during the progressive development of amebic colitis (6–8, 21). To explore this, we studied DSS-induced colitis in animals deficient in Muc2. We observed that there was a modest similar increase in Cramp mRNA expression in Muc2+/+ and Muc2−/− littermates at day 7 (Fig. 6C) during severe colitis where the mucus layer and goblet cells are depleted. As expected, during restitution on day 15, when the mucus layer and goblet cells returned to normal, Cramp mRNA expression was significantly enhanced in Muc2+/+ but not Muc2−/− littermates. These results were confirmed by immunofluorescence assays demonstrating that during peak colitis at day 7, Cramp immunoreactivity staining was reduced in the cytoplasm of colonic epithelial cells and in the outer lumen in Muc2−/− littermates as no mucus layer was present (Fig. 7C). At restitution on day 15, intense Cramp-immunoreactive peptide was present in colonic epithelial cells and abundant in the outer mucus layer of Muc2+/+ but not Muc2−/− littermates (Fig. 7C). These data clearly indicate that cathelicidin innate responses toward colonic injury and restitution depend on a functional and established Muc2 mucin barrier.

DISCUSSION

The colonic mucus barrier is essential in mucosal health to protect the host and indigenous microbiota while avoiding invasion by pathogens. Colonic MUC2 mucin is the first line of the innate host defense to prevent E. histolytica-induced acute proinflammatory responses (12) and invasion of the epithelium (7, 9). Embedded within the mucus layer are host defense peptides, but it is unclear whether MUC2 mucin is covalently bound to those peptides or whether MUC2 mucin and the peptides need each other to exert their protective functions. The colon is constantly exposed to butyrate produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers that regulates cathelicidin gene expression in mucosal epithelial cells (4). In this study, we describe regulatory interactions between MUC2 and butyrate-induced cathelicidins in the colonic lumen under homeostatic and inflammatory conditions induced by E. histolytica. Our data indicate that defects or depletion in MUC2 mucin in the colon, a hallmark of amebic colitis and IBD, severely affect innately constitutive expression of naturally occurring cathelicidins in mice and human colonic cells. Impaired production of MUC2 mucin and thus cathelicidin degrades intestinal epithelial defenses and will likely negatively impact the outcome of infectious processes.

In amebic colitis, epithelial responses to E. histolytica involve a complex interplay between its virulence factors and a variety of innate factors. Cysteine proteinases released by E. histolytica could convert human pro-IL-1β into biologically active IL-1β (30). Thus, in E. histolytica colitis, mucosal epithelial cells theoretically could be exposed to high levels of IL-1β to stimulate proinflammatory mediators (30). However, activation of cathelicidins seems to be unresponsive to IL-1β. Previous studies (4) have shown that IL-1β alone did not alter cathelicidin levels in colonic epithelial cells. In agreement, we showed that high doses of IL-1β (20 ng/ml) moderately induced cathelicidins in colonic epithelial cells (3-fold at gene level). In addition, IL-1β did not further augment LL-37 responses in colonic cells already exposed to butyrate and E. histolytica. Thus, we conclude that E. histolytica alone did not induce the expression of cathelicidin in colonic epithelial cells and that IL-1β by itself is not the main component responsible for expression of cathelicidin. Butyrate is the principal inducer of cathelicidins as it primes colonic epithelial cells to be more responsive to other stimuli, such as E. histolytica or IL-1β. From the host perspective, the cathelicidin response in the colonic mucosa may limit amebic colitis. We found that cathelicidin peptides bound fixed E. histolytica, suggesting the physical binding of these cationic peptides to anionic parasite membrane structures. This coincides with our observation of cathelicidin bound to E. histolytica trophozoites in the colonic lumen of infected mice. The actual effect of cathelicidins on the survival of E. histolytica is still elusive. Synthetic cathelicidin-derived peptides were shown to impair E. histolytica integrity and viability (14). Moreover, although E. histolytica-secreted cysteine proteinases degrade cathelicidins, the fragmented cathelicidin peptides have potent bactericidal effects over enteric bacteria that could control E. histolytica colonization (13). Thus, the absence of mucin and/or the insufficient butyrate that leads to deficient cathelicidin responses weakens epithelial innate defenses and likely induces colonic dysbiosis that could play a role the pathogenesis of E. histolytica. In agreement, the roles of cathelicidins and MUC2 in intestinal defense against other enteric pathogens have been well demonstrated. For example, Clostridium difficile or toxin A was shown to induce early protective cathelicidin Camp mRNA and peptide in the intestinal epithelium of mice (31). In addition, exogenous cathelicidins reduced histological damage, macrophage infiltration, myeloperoxidase activity, and TNF-α expression in experimentally induced C. difficile colitis (31). The interconnected protective effects of MUC2 and cathelicidins in the intestine are apparently not exclusively dependent on the presence of pathogens. Mice with an impaired Muc2 mucin barrier also showed an accompanying failure in the cathelicidin response in DSS-induced colitis. However, in DSS-induced inflammation in intact animals, the increase in cathelicidin was shown to be protective in the mucosal epithelium, whereas cathelicidin-deficient mice developed more severe colitis (20, 29). Our studies have found that other innate host defenses such as MUC2 and butyrate are critically important to elicit high cathelicidin levels toward E. histolytica and chemically induced colitis.

At present, it is not known how MUC2 mucin regulates cathelicidin. Colonic columnar epithelial cells and goblet cells produce and store MUC2 mucin and host defense peptides, including cathelicidins (4, 32). However, the regulatory signaling pathways between MUC2 and cathelicidins in the intestinal epithelium remain largely unknown. In our study, we found that the synthesis of cathelicidins was restricted to human colonic epithelial cells and to mouse models genetically capable of producing Muc2. Mechanistically, we showed that the accumulation of intracellular cAMP-activating protein kinase and activation of MAPK concurrently induced both MUC2 and LL-37 and restored the MUC2 effect in colonic cells deprived of MUC2. We have previously shown that cAMP agonist stimulated the secretion of preformed and newly synthesized mucin (26, 33). Moreover, cAMP signaling regulates cathelicidin expression by binding CREB and activator protein 1 (AP-1) to the promoter region (25). Thus, we speculate that MUC2 functions as a cAMP ligand to induce the production of cathelicidins from the colonic epithelium. Colonic epithelial cells deficient in MUC2 would have the signaling receptors to produce cathelicidins but lack the ligand (i.e., MUC2). In the intrinsic signaling pathways between MUC2 and cathelicidins in the colonic epithelium, we also demonstrated the importance of dietary compounds such as butyrate on colon cell differentiation for the production of MUC2 and cathelicidins. Other studies have shown individually the effects of butyrate on innate intestinal epithelial defenses. Butyrate increases MUC2 mRNA via AP-1 and acetylation/methylation of histones at the MUC2 promoter (34) and cathelicidin LL-37 in colonic epithelial cells via MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38/MAPK signaling pathways (35). Several other mechanisms of cooperation between MUC2 and cathelicidin and the involvement of other signaling pathways beyond cAMP may figure in intestinal defenses.

Mucus might function as a reservoir for the accumulation of antimicrobial defensins as seen in the immunofluorescence images. Recently, it was shown that rectal mucin reversibly binds and retains several antimicrobial peptides, including human β-defensin 1 and cathelicidin, that display antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus, and Gram-negative bacteria, including Bacteroides fragilis and Escherichia coli, and the yeast Candida albicans (36). Alternatively, MUC2 mucin may promote the induction of cathelicidins through the activation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs). LL-37 was shown to be upregulated via stimulation of TLR-2, TLR-4, and TLR-9 in monocyte-derived macrophages (37). It is also possible that MUC2 and cathelicidins might establish certain types of physical interactions; LL-37 was shown to bind O-glycosylated MUC2 membrane mucin (38). However, at the functional level, MUC2 may reduce the antimicrobial effect of cathelicidins. We have recently shown that MUC2 mucin inhibits the in vitro antimicrobial effect of human β-defensin 2 against enteropathogenic and nonpathogenic E. coli (21). Even though MUC2 regulates the expression and function of host defense peptides, including cathelicidins and β-defensins in the colon (21), cathelicidins may also promote the synthesis of colonic mucin. Intrarectal administration of synthetic cathelin-related peptide or mCRAMP-expressing plasmid ameliorated DSS-induced colitis in mice genetically deficient in cathelicidin by preserving mucus thickness and inducing the expression of Muc1, Muc3, Muc4, and, in particular, Muc2 mucin genes (29, 39). Further studies showed that LL-37 stimulated mucus synthesis and the expression of MUC1 and MUC2 via the MAPK pathway (40, 41).

The complex interplay between innate host defense molecules at the mucosal surface is an emerging field, and we are now beginning to appreciate significant cooperation between these molecules to exert their protective functions. The intestinal epithelium is sheltered by MUC2 mucin and commensal bacteria that release a variety of compounds, including butyrate, that limit exposure to threats to the epithelium. Our studies clearly show that intracellular and exogenous MUC2 mucin and butyrate are critical to promote the synthesis of cathelicidins and their response to infection and chemically induced colitis. Thus, defects in mucin biosynthesis or alterations in the mucus barrier accompanied by deficient production of butyrate predispose to a deficient cathelicidin response and intestinal defenses against enteropathogenic bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Entamoeba histolytica.

E. histolytica (HM-1:IMSS) was grown axenically in TYI-S-3 medium with 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate at 37°C in sealed 15-ml borosilicate glass tubes and regularly passaged through gerbil livers to maintain high virulence (32). Trophozoites were harvested during the logarithmic growth phase (48 to 72 h) by being chilled on ice for 10 min and pelleted by centrifugation at 200 × g (5 min at 4°C).

Purification of human colonic mucin.

Secreted MUC2 mucin was purified from human LS174T goblet cells as previously described (21, 32). We used secreted rather than intracellular MUC2 mucin because it is native polymeric mucin and best represents the physiological mucus layer. LS174T cells constitutively express and secrete high levels of MUC2 mRNA (42), have low expression of MUC1 with no MUC3 or MUC4 (43), and secrete high-density hexose-rich fractions rich in serine, threonine, proline, N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), and galactose (Gal) typical of native secreted human colonic mucin (32). In brief, cell-free supernatants derived from 80% confluent cells were centrifuged (300 × g) for 5 min at 4°C, dialyzed against deionized water (12,000- to 14,000-molecular-weight cutoff [MWCO]; SpectraPor; Spectra Labs), and lyophilized. Crude lyophilized mucus (100 mg) was dissolved in Tris-HCl buffer (0.01 M) containing 0.001% sodium azide (pH 8.0; Sigma) and fractionated (100 mg/column) on an equilibrated Sepharose 4B gel filtration column (2.5 by 50 cm; Bio-Rad) (column flow rate, 12 ml/h). High-molecular-weight mucin fractions in the void volume (V0) (fractions 25 to 30) were pooled, dialyzed against deionized water (4°C), and concentrated (SpinX UF, 10,000 MW; Corning). The V0 mucin (2 mg) were digested with DNase (1 mg) and RNase (2 mg) and subjected to CsCl density gradient ultracentrifugation (starting density, 1.41 g/ml) to purify MUC2 (>1.46 g/ml). Fractions were run on a 1.2% agarose gel under reducing conditions and Western blotted with affinity-purified rabbit IgG anti-CsCl purified LS174T mucin antibody (32). To validate the presence of MUC2 only, purified MUC2 CsCl fractions (1 μg) were run on a 1.2% agarose gel and Western blotted with affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-MUC2, mouse monoclonal anti-MUC5AC (Santa Cruz), and goat polyclonal anti-MUC5B (Santa Cruz) antibodies (21). Protein concentration was estimated using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Pierce, Thermo Scientific) (21).

Human colonic epithelial cells.

The parental human adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line HT-29 was used. This cell line does not produce substantial amounts of MUC2 but produces cathelicidins under inductive stimuli (4). HT-29 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (catalog no. 12430; Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (BenchMark; Gemini), sodium pyruvate (1 mM) (catalog no. 11360; Gibco), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml; HyClone Thermo) in a humidified environment of 95% air and 5% CO2. To determine if MUC2 could alter the synthesis of cathelicidins, we used a high-mucin-producing clone (44) of HT-29 (clone HT-29 C16) obtained by prolonged treatments with butyrate designated MUC2 H. In addition, we used a derivate clone from MUC2 H silenced by lentivirus short hairpin RNA (shRNA) designated MUC2 L as previously described (21). Briefly, hairpin MUC2 shRNA sequences comprising a 21-bp stem and a 6-bp loop were cloned into pLKO.1 viral vectors and cotransfected into HEK293T packaging cells along with an envelope and a packaging plasmid (Invitrogen). Viral particles containing the transfected shRNA plasmid were collected, concentrated by ultracentrifugation, and titrated. To achieve maximal MUC2 silencing, the viral particles were transduced/infected in colonic epithelial cells in the presence of Polybrene. The transduced cells were then selected with puromycin. Using this procedure, the virus integrated into the host genome along with the MUC2 shRNA, and only cell lines with low MUC2 expression (MUC2 L) were generated. MUC2 shRNA-silenced MUC2 L cells showed low MUC2 gene expression (less than 10%) with no significant compensatory effects on the low basal levels of MUC5AC and MUC5B (21).

Colonic epithelial cells were grown in tissue culture plates with 12 or 24 wells (Corning Costar) until 80% confluent, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and stimulated with the following agonists: butyrate (catalog no. B5887; Sigma) for up to 72 h with replenishment every 24 h with the same medium; IL-1β (catalog no. 200-01A; Peprotech), forskolin (FSK) (catalog no. 3828; Cell Signaling) (10 μM), or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (catalog no. P1585; Sigma) for 3 h; or purified MUC2 mucin (up to 10 μg/ml) or E. histolytica trophozoites (1 × 104/ml) for 1 h. In replicate experiments, HT-29 cells were preincubated with the MAPK kinase inhibitor (MAPK/ERK kinase; PD98059; 25 μM for 1 h). This MAPK/ERK inhibitor specifically inhibits binding to the ERK-specific MAPK MEK, therefore preventing phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (p44/p42 MAPK) by MEK1/2. In addition, cells were preincubated with a morpholine-containing chemical inhibitor of phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks; LY294002) (50 μM; 1 h) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Mice.

All studies were approved by the University of Calgary Animal Care Committee. Male 10- to 12-week-old C57BL/6 wild-type mice from Charles River and Muc2−/− (44) mice of the same genetic background were bred in-house, and F1 Muc2+/− mice were backcrossed to generate F2 Muc2+/+, Muc2+/−, and Muc2−/− littermates. Mice were maintained in sterilized and filter-top cages under specific-pathogen-free conditions and provided food and water ad libitum.

Models of colitis.

Colonic loops were used as a model for short acute infection with E. histolytica in mice (33). Animals were subjected to fasting overnight and anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with sodium pentobarbital dissolved in sterile water (4.2 mg/kg of body weight) (Ceva Santé Animale). A laparotomy was performed to exteriorize the large intestine, and a loop (3 cm) was made at the proximal portion of the colon immediately after the cecum by two ligations with 3.0 black silk sutures (Ethicon Inc., Peterborough, Ontario, Canada). E. histolytica trophozoites (106) in log phase suspended in 100 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.3, were inoculated into the loop. Care was taken to keep the mesenteries, blood vessels, and nerves intact. Mice were maintained under surveillance for up to 4 h and then sacrificed by cervical dislocation.

To investigate the role of Muc2 and cathelicidins in chronic colitis, dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) (MP Biochemicals; 36,000 to 50,000 MW) dissolved in drinking tap water was given to Muc2+/+ mice (3% DSS) for five consecutive days or Muc2−/− mice (1% DSS) for 3 days (12). This differential DSS treatment was necessary to obtain similar histological damage scores between Muc2+/+ and Muc2−/− mice (12). Mice were then maintained on tap water and sacrificed by cervical dislocation on days 7 and 15 (day 0 is the beginning of the DSS treatment). The amounts of water drunk and weight were examined daily, and the disease activity index (DAI) was calculated based on weight loss, stool consistency, blood loss, and appearance. In all mice, the entire colon was externalized aseptically and fresh samples up to 2 cm in diameter were homogenized in liquid nitrogen for quantitative PCR (qPCR) studies. In parallel, fresh colon tissue was fixed in Carnoy's fixative (60% ethanol 100%, 30% chloroform, 10% glacial acetic acid) for 3 h to preserve the mucus layers, transferred to ethanol 100% at 4°C, and then embedded in paraffin blocks for confocal immunofluorescence studies.

Expression of cathelicidin and MUC2 mRNA in human colonic epithelial cells and murine colon.

MUC2 and cathelicidin (LL-37 from human colonic epithelial cells and Cramp from murine colonic mucosa) gene expression was examined by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). Total RNA was extracted from human goblet cells and homogenized frozen murine colon by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and RNA purity and yield were assessed with a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop; Thermo Scientific). cDNA was prepared from 1 μg of total RNA using Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase (catalog no. 95048; qScript cDNA SuperMix; Quanta Biosciences). Absence of contaminating genomic DNA from RNA preparations was checked using a minus-reverse-transcriptase control (i.e., a sample with all the RT-PCR reagents except reverse transcriptase). Reactions were performed in a Rotor-Gene 3000 real-time PCR system (Corbett Research). Each reaction mixture (total, 25 μl) contained 100 ng of cDNA (10 μl), 2× Rotor-Gene SYBR green PCR master mix (catalog no. 204072; Qiagen) (12.5 μl), and 1 μM primers (2.5 μl). The primers used were as follows: for human LL-37, CAMP, PPH09430A, GenBank accession no. NM_004345.3; MUC2, forward, 5′-CAGCACCGATTGCTGAGTTG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCTGGTCATCTCAATGGCAG-3′; and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), sense, 5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′, and antisense, 5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′. For mouse, we used Cramp (Camp; PPM25023A; GenBank accession no. NM_009921.2; RT2 qPCR primer assay [Qiagen]) and murine actin (sense, 5′-CTACAATGAGCTGCGTGTG-3′; antisense, 5′-TGGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTC-3′). The primers used (RT2 qPCR primer assay sourced from Qiagen) were experimentally verified for specificity and efficiency. Amplification of a single product of the correct size with SYBR green was guaranteed to have high PCR efficiency (>90%). The reaction mixtures were incubated for 95°C for 5 min, followed by denaturation for 5 s at 95°C and combined annealing/extension for 10 s at 60°C for a total of 40 cycles. Target mRNA values were corrected relative to the housekeeping genes coding for human GAPDH and murine actin, respectively. Two housekeeping genes, GAPDH and β-actin, were initially tested, and because both showed no alterations under our treatments, we proceeded using the former gene. All experiments were done in triplicates (i.e., on three different independent occasions, with independent samples and treatments), and in each experiment, treatments were done in triplicates. Data were analyzed using the threshold cycle (2−ΔΔCT) method and expressed as fold change (mean ± standard error [SE]). For comparison of MUC2 H with MUC2 L, untreated cells from the same type were used as controls. Likewise, data from nonchallenged Muc2+/+ mice served as the control for Muc2+/+ challenged with E. histolytica while nonchallenged Muc2−/− mice served as the control for Muc2−/− mice challenged with E. histolytica.

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy.

Location of cathelicidin CRAMP was studied in the colon of Muc2+/+ and Muc2−/− mice, and that of cathelicidin LL-37 was studied in colonic epithelial cells. Colonic tissues fixed in Carnoy's fixative were sectioned (7 μm) and deparaffinized with a xylene substitute (Neo-Clear; Millipore), followed by decreasing concentrations of ethanol and running tap water (3 min each). Slides were boiled in 10 mM sodium citrate (catalog no. S4641; Sigma) plus 0.05% Tween 20 (pH 6) for 20 min in a microwave oven for antigen retrieval and then cooled at room temperature (RT) and rinsed in PBS. Free aldehydes were blocked by 0.1 M glycine in PBS for 10 min at RT. Human colonic epithelial cells were grown in 12-well plates and pretreated with butyrate (4 mM; 72 h) and purified MUC2 mucin (20 μg/ml), IL-1β (20 ng/ml), or forskolin (10 μM) or exposed to E. histolytica (1 × 104 trophozoites/ml) for 30 min. Cells were rinsed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde with 150 mM NaCl, 4 mM NaH2PO4, and 5 mM KCl (pH 7.4) for 10 min at RT. Sections were rinsed in cold PBS plus Tween 0.05% (pH 7.2) (PBS-Tw), permeabilized with PBS-Tw plus 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 min at RT, and rinsed in cold PBS-Tw. Histologic sections from murine colon and human colonic cells were blocked with PBS-Tw, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 10% goat serum, 0.3 M glycine, and 0.05% saponin for 2 h at RT and rinsed with PBS-Tw. Sections from murine colon were exposed to affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal IgG anti-mouse Cramp antibodies (Ab74868; Abcam), and HT-29 cells were exposed to monoclonal murine IgG anti-human LL-37 (Ab87701, OSX12; Abcam) and affinity-purified goat IgG anti-human MUC2 (Santa Cruz) antibodies. Primary antibodies were diluted 1:100 in PBS-Tw with 0.05% saponin and incubated at 4°C overnight in a humid chamber. As secondary antibodies, HT-29 cells were blotted with DyLight 647 affinity-purified donkey anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 fragment-specific antibodies and DyLight 594 affinity-purified donkey anti-goat IgG F(ab′)2 fragment-specific antibodies, and murine tissues were blotted with DyLight 647 affinity-purified donkey anti-rabbit IgG F(ab′)2 fragment-specific antibodies. Secondary antibodies were diluted 1:1,000 in PBS-Tw plus 1% bovine serum albumin and incubated for 1 h at RT. Sections were rinsed in cold PBS-Tw, and nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Sections were rinsed with cold PBS-Tw and mounted with FluorSave reagent (Calbiochem). Slides were examined using a FluoView FV1000 confocal immunofluorescence microscope (Olympus).

To define the interaction between cathelicidin peptides and E. histolytica, confocal microscopy studies were conducted on E. histolytica (3 × 105 trophozoites) previously fixed with glutaraldehyde (1%) incubated with synthetic cathelicidin LL-37 (5 μM) for 1 h in a 100-μl reaction mixture in microtubes. Trophozoites were rinsed in cold PBS-Tw, permeabilized with PBS-Tw plus 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 min at RT, and rinsed in cold PBS-Tw. Cells were blocked with PBS-Tw, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 10% goat serum, 0.3 M glycine, and 0.05% saponin for 2 h at RT and rinsed with PBS-Tw. Then, cells were exposed to monoclonal murine IgG anti-LL-37 antibodies (OSX12; Novus Bio) (1:100 in PBS-Tw) and incubated at RT for 2 h in a humid chamber. As secondary antibodies, cells were blotted with DyLight 594 affinity-purified donkey anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 fragment-specific antibodies (1:1,000 in PBS-Tw plus 1% bovine serum albumin) and incubated for 1 h at RT. Sections were rinsed with cold PBS-Tw and mounted with FluorSave reagent (Calbiochem). Slides were examined using a FluoView FV1000 confocal immunofluorescence microscope (Olympus). Quantitative statistical comparison of staining fluorescence intensity between groups was performed using Image Processing and Analysis in Java (Image J; NIH). Image files were processed as TIFF file formats, and cell areas were selected to determine fluorescence index. Areas of the image with similar numbers of cells and uniform background were randomly selected. Data represented in a histogram are means and standard errors of the means from at least three images from independent experiments.

Statistical analysis.

Results were normally distributed and reported as means and standard errors of the means from at least three independent experiments. Statistical difference comparisons were conducted between treated and untreated/control groups. Data from qPCR and fluorescence intensity were analyzed by a nonpaired two-tailed Student t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) versus the control, followed by a post hoc Bonferroni posttest (GraphPad Prism 5.0 Mac; GraphPad Software). Graphs represent two to three independent experiments, and error bars represent means ± standard errors. Differences in values were considered significant when P was <0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) to K.C. E.R.C. was supported by an Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions Fellowship Award. The Live Cell Imaging Facility is funded by an equipment and infrastructure grant from the Canadian Foundation Innovation (CFI) and the Alberta Science and Research Authority.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johansson ME, Phillipson M, Petersson J, Velcich A, Holm L, Hansson GC. 2008. The inner of the two Muc2 mucin-dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:15064–15069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803124105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallo RL, Kim KJ, Bernfield M, Kozak CA, Zanetti M, Merluzzi L, Gennaro R. 1997. Identification of CRAMP, a cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide expressed in the embryonic and adult mouse. J Biol Chem 272:13088–13093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaiou M, Gallo RL. 2002. Cathelicidins, essential gene-encoded mammalian antibiotics. J Mol Med (Berl) 80:549–561. doi: 10.1007/s00109-002-0350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hase K, Eckmann L, Leopard JD, Varki N, Kagnoff MF. 2002. Cell differentiation is a key determinant of cathelicidin LL-37/human cationic antimicrobial protein 18 expression by human colon epithelium. Infect Immun 70:953–963. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.953-963.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanley SL., Jr 2003. Amoebiasis. Lancet 361:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornick S, Moreau F, Chadee K. 2016. Entamoeba histolytica cysteine proteinase 5 evokes mucin exocytosis from colonic goblet cells via alphavbeta3 integrin. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005579. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moncada D, Keller K, Chadee K. 2003. Entamoeba histolytica cysteine proteinases disrupt the polymeric structure of colonic mucin and alter its protective function. Infect Immun 71:838–844. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.838-844.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moncada D, Yu Y, Keller K, Chadee K. 2000. Entamoeba histolytica cysteine proteinases degrade human colonic mucin and alter its function. Arch Med Res 31:S224–S225. doi: 10.1016/S0188-4409(00)00227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lidell ME, Moncada DM, Chadee K, Hansson GC. 2006. Entamoeba histolytica cysteine proteases cleave the MUC2 mucin in its C-terminal domain and dissolve the protective colonic mucus gel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:9298–9303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600623103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mortimer L, Moreau F, Cornick S, Chadee K. 2014. Gal-lectin-dependent contact activates the inflammasome by invasive Entamoeba histolytica. Mucosal Immunol 7:829–841. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mortimer L, Moreau F, Cornick S, Chadee K. 2015. The NLRP3 inflammasome is a pathogen sensor for invasive Entamoeba histolytica via activation of alpha5beta1 integrin at the macrophage-amebae intercellular junction. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004887. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kissoon-Singh V, Moreau F, Trusevych E, Chadee K. 2013. Entamoeba histolytica exacerbates epithelial tight junction permeability and proinflammatory responses in Muc2(−/−) mice. Am J Pathol 182:852–865. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cobo ER, He C, Hirata K, Hwang G, Tran U, Eckmann L, Gallo RL, Reed SL. 2012. Entamoeba histolytica induces intestinal cathelicidins but is resistant to cathelicidin-mediated killing. Infect Immun 80:143–149. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05029-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rico-Mata R, De Leon-Rodriguez LM, Avila EE. 2013. Effect of antimicrobial peptides derived from human cathelicidin LL-37 on Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites. Exp Parasitol 133:300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pullan RD, Thomas GA, Rhodes M, Newcombe RG, Williams GT, Allen A, Rhodes J. 1994. Thickness of adherent mucus gel on colonic mucosa in humans and its relevance to colitis. Gut 35:353–359. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCormick DA, Horton LW, Mee AS. 1990. Mucin depletion in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pathol 43:143–146. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gersemann M, Becker S, Kubler I, Koslowski M, Wang G, Herrlinger KR, Griger J, Fritz P, Fellermann K, Schwab M, Wehkamp J, Stange EF. 2009. Differences in goblet cell differentiation between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Differentiation 77:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schauber J, Rieger D, Weiler F, Wehkamp J, Eck M, Fellermann K, Scheppach W, Gallo RL, Stange EF. 2006. Heterogeneous expression of human cathelicidin hCAP18/LL-37 in inflammatory bowel diseases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 18:615–621. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200606000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dharmani P, Leung P, Chadee K. 2011. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and Muc2 mucin play major roles in disease onset and progression in dextran sodium sulphate-induced colitis. PLoS One 6:e25058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koon HW, Shih DQ, Chen J, Bakirtzi K, Hing TC, Law I, Ho S, Ichikawa R, Zhao D, Xu H, Gallo R, Dempsey P, Cheng G, Targan SR, Pothoulakis C. 2011. Cathelicidin signaling via the Toll-like receptor protects against colitis in mice. Gastroenterology 141:1852–1863. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cobo ER, Kissoon-Singh V, Moreau F, Chadee K. 2015. Colonic MUC2 mucin regulates the expression and antimicrobial activity of beta-defensin 2. Mucosal Immunol 8:1360–1372. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schauber J, Dorschner RA, Yamasaki K, Brouha B, Gallo RL. 2006. Control of the innate epithelial antimicrobial response is cell-type specific and dependent on relevant microenvironmental stimuli. Immunology 118:509–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Augeron C, Laboisse CL. 1984. Emergence of permanently differentiated cell clones in a human colonic cancer cell line in culture after treatment with sodium butyrate. Cancer Res 44:3961–3969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen GY, Nunez G. 2011. Inflammasomes in intestinal inflammation and cancer. Gastroenterology 141:1986–1999. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakraborty K, Maity PC, Sil AK, Takeda Y, Das S. 2009. cAMP stringently regulates human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide expression in the mucosal epithelial cells by activating cAMP-response element-binding protein, AP-1, and inducible cAMP early repressor. J Biol Chem 284:21810–21827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epple HJ, Kreusel KM, Hanski C, Schulzke JD, Riecken EO, Fromm M. 1997. Differential stimulation of intestinal mucin secretion by cholera toxin and carbachol. Pflugers Arch 433:638–647. doi: 10.1007/s004240050325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang A, Si H, Liu D, Jiang H. 2012. Butyrate activates the cAMP-protein kinase A-cAMP response element-binding protein signaling pathway in Caco-2 cells. J Nutr 142:1–6. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.148155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y, Garvin LM, Nickola TJ, Watson AM, Colberg-Poley AM, Rose MC. 2014. IL-1beta induction of MUC5AC gene expression is mediated by CREB and NF-kappaB and repressed by dexamethasone. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 306:L797–L807. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00347.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tai EK, Wu WK, Wang XJ, Wong HP, Yu L, Li ZJ, Lee CW, Wong CC, Yu J, Sung JJ, Gallo RL, Cho CH. 2013. Intrarectal administration of mCRAMP-encoding plasmid reverses exacerbated colitis in Cnlp(−/−) mice. Gene Ther 20:187–193. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Z, Wang L, Seydel KB, Li E, Ankri S, Mirelman D, Stanley SL Jr. 2000. Entamoeba histolytica cysteine proteinases with interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme (ICE) activity cause intestinal inflammation and tissue damage in amoebiasis. Mol Microbiol 37:542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hing TC, Ho S, Shih DQ, Ichikawa R, Cheng M, Chen J, Chen X, Law I, Najarian R, Kelly CP, Gallo RL, Targan SR, Pothoulakis C, Koon HW. 2013. The antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin modulates Clostridium difficile-associated colitis and toxin A-mediated enteritis in mice. Gut 62:1295–1305. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belley A, Keller K, Grove J, Chadee K. 1996. Interaction of LS174T human colon cancer cell mucins with Entamoeba histolytica: an in vitro model for colonic disease. Gastroenterology 111:1484–1492. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(96)70009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belley A, Chadee K. 1999. Prostaglandin E(2) stimulates rat and human colonic mucin exocytosis via the EP(4) receptor. Gastroenterology 117:1352–1362. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burger-van Paassen N, Vincent A, Puiman PJ, van der Sluis M, Bouma J, Boehm G, van Goudoever JB, van Seuningen I, Renes IB. 2009. The regulation of intestinal mucin MUC2 expression by short-chain fatty acids: implications for epithelial protection. Biochem J 420:211–219. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schauber J, Svanholm C, Termen S, Iffland K, Menzel T, Scheppach W, Melcher R, Agerberth B, Luhrs H, Gudmundsson GH. 2003. Expression of the cathelicidin LL-37 is modulated by short chain fatty acids in colonocytes: relevance of signalling pathways. Gut 52:735–741. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.5.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antoni L, Nuding S, Weller D, Gersemann M, Ott G, Wehkamp J, Stange EF. 2013. Human colonic mucus is a reservoir for antimicrobial peptides. J Crohns Colitis 7:652–664. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rivas-Santiago B, Hernandez-Pando R, Carranza C, Juarez E, Contreras JL, Aguilar-Leon D, Torres M, Sada E. 2008. Expression of cathelicidin LL-37 during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in human alveolar macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, and epithelial cells. Infect Immun 76:935–941. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01218-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swidergall M, Ernst AM, Ernst JF. 2013. Candida albicans mucin Msb2 is a broad-range protectant against antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3917–3922. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00862-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tai EK, Wu WK, Wong HP, Lam EK, Yu L, Cho CH. 2007. A new role for cathelicidin in ulcerative colitis in mice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 232:799–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tai EK, Wong HP, Lam EK, Wu WK, Yu L, Koo MW, Cho CH. 2008. Cathelicidin stimulates colonic mucus synthesis by up-regulating MUC1 and MUC2 expression through a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Cell Biochem 104:251–258. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otte JM, Zdebik AE, Brand S, Chromik AM, Strauss S, Schmitz F, Steinstraesser L, Schmidt WE. 2009. Effects of the cathelicidin LL-37 on intestinal epithelial barrier integrity. Regul Pept 156:104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bu XD, Li N, Tian XQ, Huang PL. 2011. Caco-2 and LS174T cell lines provide different models for studying mucin expression in colon cancer. Tissue Cell 43:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hollingsworth MA, Strawhecker JM, Caffrey TC, Mack DR. 1994. Expression of MUC1, MUC2, MUC3 and MUC4 mucin mRNAs in human pancreatic and intestinal tumor cell lines. Int J Cancer 57:198–203. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Velcich A, Yang W, Heyer J, Fragale A, Nicholas C, Viani S, Kucherlapati R, Lipkin M, Yang K, Augenlicht L. 2002. Colorectal cancer in mice genetically deficient in the mucin Muc2. Science 295:1726–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.1069094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]