ABSTRACT

Substitutions in the LiaFSR membrane stress pathway are frequently associated with the emergence of antimicrobial peptide resistance in both Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium. Cyclic di-AMP (c-di-AMP) is an important signal molecule that affects many aspects of bacterial physiology, including stress responses. We have previously identified a mutation in a gene (designated yybT) in E. faecalis that was associated with the development of daptomycin resistance, resulting in a change at position 440 (yybTI440S) in the predicted protein. Here, we show that intracellular c-di-AMP signaling is present in enterococci, and on the basis of in vitro physicochemical characterization, we show that E. faecalis yybT encodes a cyclic dinucleotide phosphodiesterase of the GdpP family that exhibits specific activity toward c-di-AMP by hydrolyzing it to 5′pApA. The E. faecalis GdpPI440S substitution reduces c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase activity more than 11-fold, leading to further increases in c-di-AMP levels. Additionally, deletions of liaR (encoding the response regulator of the LiaFSR system) that lead to daptomycin hypersusceptibility in both E. faecalis and E. faecium also resulted in increased c-di-AMP levels, suggesting that changes in the LiaFSR stress response pathway are linked to broader physiological changes. Taken together, our data show that modulation of c-di-AMP pools is strongly associated with antibiotic-induced cell membrane stress responses via changes in GdpP activity or signaling through the LiaFSR system.

KEYWORDS: Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, GdpP, LiaFSR, membrane stress, c-di-AMP, cyclic dinucleotide, daptomycin, enterococci

INTRODUCTION

Cyclic di-AMP (c-di-AMP) is a recently discovered second messenger molecule found in a wide range of bacteria and archaea (1), including Bacillus subtilis (2), Listeria monocytogenes (3), Staphylococcus aureus (4), Streptococcus pyogenes (5), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (6). In vivo levels of c-di-AMP are typically maintained by diadenyl cyclases that synthesize c-di-AMP from two molecules of ATP and by phosphodiesterases that degrade c-di-AMP to 5′pApA (7, 8). While c-di-AMP appears to be essential for bacteria that produce it, the accumulation of c-di-AMP can also be toxic or inhibit growth (9).

c-di-AMP plays important roles in the regulation of diverse cellular pathways, including potassium homeostasis, biofilm formation, and cell wall biosynthesis (4, 10, 11). Increased intracellular c-di-AMP levels in bacteria have been associated with increased tolerance to a wide range of environmental challenges, including cell wall damage, high temperatures, starvation, and acid stress, as well as some antibiotics, including lysostaphin, oxacillin, and penicillin G (4, 11, 12). While many genes regulated by c-di-AMP have been reported (10), the signal transduction pathways that convert environment stresses to c-di-AMP signals have not been identified, though it has been suggested that membrane-associated enzymes such as c-di-AMP synthase A (CdaA, also referred as YbbP) and its regulator CdaR (c-di-AMP synthase A regulator, also referred to as YybR) may sense damage directly (2, 7, 13). The cyclic dinucleotide signaling pathway and its potential role in stress response have not been characterized in enterococci.

Enterococci are facultative anaerobic Gram-positive bacteria and are the cause of multiple human infections, including endocarditis, bacteremia, and urinary tract infections (14). The acquisition of multiple resistance determinants has made vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) a serious public health threat with strains that are resistant to almost all antibiotics clinically available (15). VRE infections usually affect critically ill and immunocompromised patients with increased prevalence in health care-associated infections (9,820 in 2000 to 20,000 in 2013 in the United States) (16). The cyclic lipopeptide daptomycin is frequently used as a drug of last resort against recalcitrant VRE infections (15, 17). Daptomycin is a bactericidal antibiotic that targets the cell membrane in a calcium- and phosphatidylglycerol-dependent manner leading to cell death after disrupting the cell membrane (18).

In a previous study, we used quantitative experimental evolution of a polymorphic population of Enterococcus faecalis S613 to identify common evolutionary trajectories leading to daptomycin resistance (19). All of the initial mutations associated with resistance appeared directly within the liaFSR pathway, including liaF and liaR (19, 20). LiaFSR is a three-component membrane stress response regulon (21) that includes a transmembrane histidine kinase (LiaS) that is predicted to activate its cognate response regulator (LiaR) by phosphorylation in response to cell envelope stress (22). Upon activation, LiaR regulates downstream genes by binding DNA in a sequence-specific manner, including the liaFSR and liaXYZ operons (19, 22, 23). Studies with B. subtilis have suggested that LiaF is an inhibitor of LiaS that attenuates the signal response (21, 22).

After an initial set of mutations within the LiaFSR pathway, a second group of genes showed clear indications of being important to adaptation to daptomycin and included cls (encoding a cardiolipin synthase) and a previously unidentified gene designated yybT (19). On the basis of primary sequence alignment, we reasoned that YybT might be a member of the GGDEF domain protein-containing phosphodiesterase family (E. faecalis yybT is referred to as gdpP here) (4). GdpP has been identified in several Gram-positive bacteria, including B. subtilis (24), Lactococcus lactis (12), S. pyogenes (5), and S. aureus (4) with roles in bacterial growth and virulence. In addition to gdpP, we were able to identify potential homologs of a c-di-AMP synthase A (CdaA) and another cyclic-dinucleotide phosphodiesterase, PgpH, in the E. faecalis genome (ADDP01000030.1) (2, 8). Thus, we postulated that if yybT is indeed a gdpP homolog, the c-di-AMP signaling pathway may be important in enterococci and may influence different processes, including the adaptive response to antimicrobial peptides like daptomycin. Interestingly, daptomycin-resistant strains containing gdpPI440S were found in association with mutations in the LiaFSR system such as liaRD191N, suggesting a potential epistatic link to the LiaFSR regulon (19). Although gdpPI440S has not been observed in clinical isolates, the possibility that it is a phosphodiesterase provided the first indication that the LiaFSR pathway, cyclic dinucleotide signaling, and daptomycin resistance might be related.

In this report, we show that c-di-AMP is a second messenger in enterococci. Using in vitro enzymatic activity assays, we show that E. faecalis GdpP is a bone fide c-di-AMP-specific phosphodiesterase. The GdpPI440S substitution identified during selection with daptomycin has reduced activity both in vitro and in vivo and leads to accumulation of c-di-AMP. Additionally, we provide data that link the LiaFSR system and changes in c-di-AMP levels. Taken together, our data suggest that the membrane stress response of enterococci via GdpP or LiaFSR signaling affects c-di-AMP levels. The changes in c-di-AMP may have important physiological implications for the adaptive response to antibiotics in enterococci.

RESULTS

The nucleotide signaling molecule c-di-AMP is present at physiologically relevant levels in enterococci.

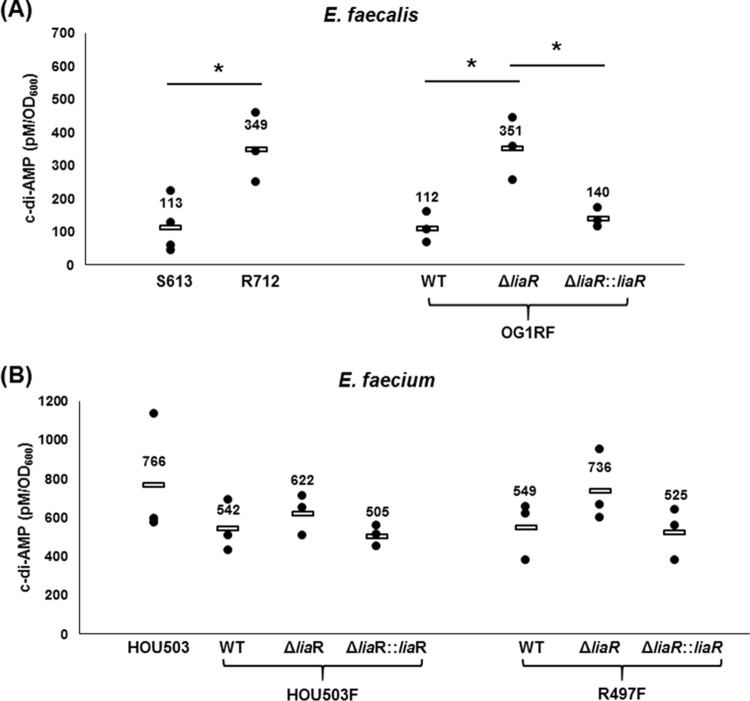

As c-di-AMP signaling has not been previously identified in enterococci, it was essential to test whether c-di-AMP was present at levels consistent with its being a second messenger in vivo. Thus, we measured c-di-AMP in E. faecalis S613 and its daptomycin-resistant derivative E. faecalis R712, a vancomycin-resistant strain pair isolated from the bloodstream of a patient before and after daptomycin treatment, respectively (14, 41). Additionally, we included a laboratory strain of E. faecalis, OG1RF (Table 1) (14, 25). Cells were collected at late exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], ∼1.0), and the concentration of c-di-AMP was measured with a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) specific for c-di-AMP (26). As shown in Fig. 1A, E. faecalis strains S613 and OG1RF produced c-di-AMP. The c-di-AMP levels of E. faecalis S613 and OG1RF at late exponential phase were 113 ± 81 and 112 ± 47 pM/OD600, respectively. In E. faecalis R712 (daptomycin-resistant derivative of E. faecalis S613), the c-di-AMP level was 349 ± 104 pM/OD600, more than 3-fold higher than that of E. faecalis S613 (Table 1 and Fig. 1A).

TABLE 1.

Enterococcal strains used in this study and measured c-di-AMP concentrations and daptomycin MICs

| Strain | Genotype or description | Avg intracellular [c-di-AMP] (pM/OD600) ± SDa | Daptomycin MICb (μg/ml) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis strains | ||||

| S613 | Wild-type clinical VREc strain | 113 ± 81 | 0.5 | 14, 41 |

| OG1RF | Wild-type laboratory vancomycin-susceptible strain | 112 ± 47 | 2 | 14, 41 |

| R712 | Clinical daptomycin-resistant strain derived from S613; liaFΔI177 clsΔK61 gdpDΔI170 | 349 ± 104 | 12 | 14, 41 |

| OG1RF_ΔliaR | ΔliaR | 351 ± 94 | 0.094 | 41 |

| OG1RF_ΔliaR::liaR | OG1RF_ΔliaR with liaR complementation in cis | 140 ± 29 | 2 | 41 |

| OG1RF::pMSP3535::gdpP | pMSP3535::gdpP-Efc | 115 ± 9 | 0.5 | This study |

| OG1RF::pMSP3535::gdpPI440S | pMSP3535::gdpPI440S-Efc | 152 ± 3 | 0.5 | This study |

| OG1RF::pMSP3535 | pMSP3535 | 158 ± 3 | 0.5 | This study |

| E. faecium strains | ||||

| HOU503 | Clinical daptomycin-tolerant VRE strain with liaRW37C and liaST120A | 766 ± 318 | 3 | 27 |

| HOU503F | HOU503 fusidic acid-resistant derivative | 542 ± 133 | 3 | 27 |

| HOU503F_ΔliaR | ΔliaR | 622 ± 104 | 0.064 | 27 |

| HOU503F_ΔliaR::liaR | HOU503F_ΔliaR with liaR complementation in cis | 505 ± 54 | 3 | 27 |

| R497F | Fusidic acid-resistant derivative of clinical daptomycin-resistant vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium strain R497 with liaRW37C, liaST120A, and clsins110 | 549 ± 150 | 24 | 27 |

| R497F_ΔliaR | ΔliaR | 736 ± 186 | 0.094 | 27 |

| R497F_ΔliaR::liaR | F497F_ΔliaR with liaR complementation in cis | 525 ± 134 | 24 | 27 |

Errors correspond to standard deviations of three individual measurements.

MICs were measured by Etest (bioMérieux) on Mueller-Hinton agar.

VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus.

FIG 1.

Enterococcal strains with mutations in the LiaFSR signaling pathway have increased c-di-AMP levels. Intracellular c-di-AMP concentrations were measured by an ELISA (26). c-di-AMP was detected in both E. faecalis (A) and E. faecium (B). (A) E. faecalis strains. The intracellular c-di-AMP level in E. faecalis OG1RF_ΔliaR that knocks out LiaFSR signaling increases to 351 ± 94 pM/OD600 (26), and complementation of liaR in cis restores the c-di-AMP level. *, P < 0.05. (B) E. faecium strains. The nonpolar liaR deletion mutation causes a small but not statistically significant increase in E. faecium HOU503F_ΔliaR and R497F_ΔliaR. Each c-di-AMP value is from at least three independent biological measurements. See Table 1 for strain descriptions. WT, wild type.

To determine whether c-di-AMP signaling is present in other enterococcal strains, daptomycin-tolerant and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium clinical isolate HOU503 and its fusidic acid-resistant derivative E. faecium HOU503F were tested (Table 1) (27). The c-di-AMP levels of E. faecium HOU503 and E. faecium HOU503F were 766 ± 318 and 542 ± 133 pM/OD600 at late exponential phase (OD600, ∼1.2) (Table 1 and Fig. 1B), both significantly higher than those of E. faecalis. Interestingly, it has been reported that the c-di-AMP level in S. pneumoniae is ∼25 pM/OD620 (6) and that c-di-AMP is present in cytoplasmic extracts from other Gram-positive bacteria. The use of alternative methods to measure c-di-AMP shows that B. subtilis has ∼1.7 μM/1-liter culture (28) and 3.33 ± 0.44 ng/mg of bacterial dry weight in S. aureus (4). While c-di-AMP signaling molecules have been identified in a number of bacteria, the presence of c-di-AMP in E. faecalis and E. faecium had not been reported before, and our results demonstrate that c-di-AMP is present in enterococci at levels sufficient to be a bone fide in vivo signal.

E. faecalis GdpP has phosphodiesterase activity.

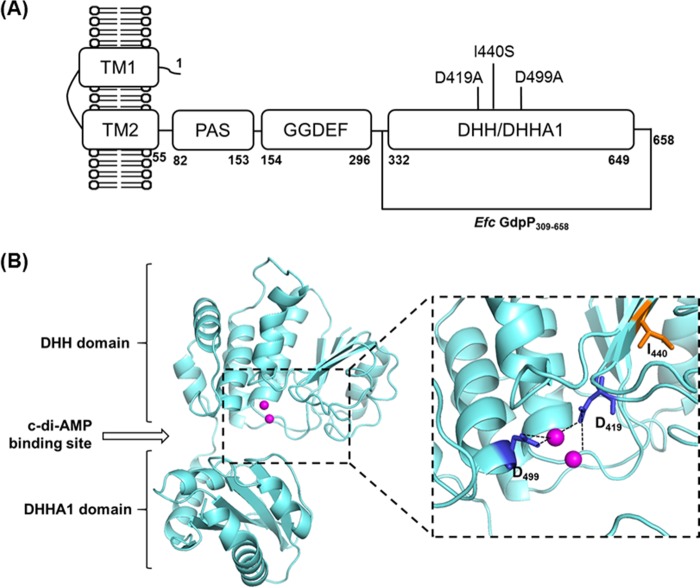

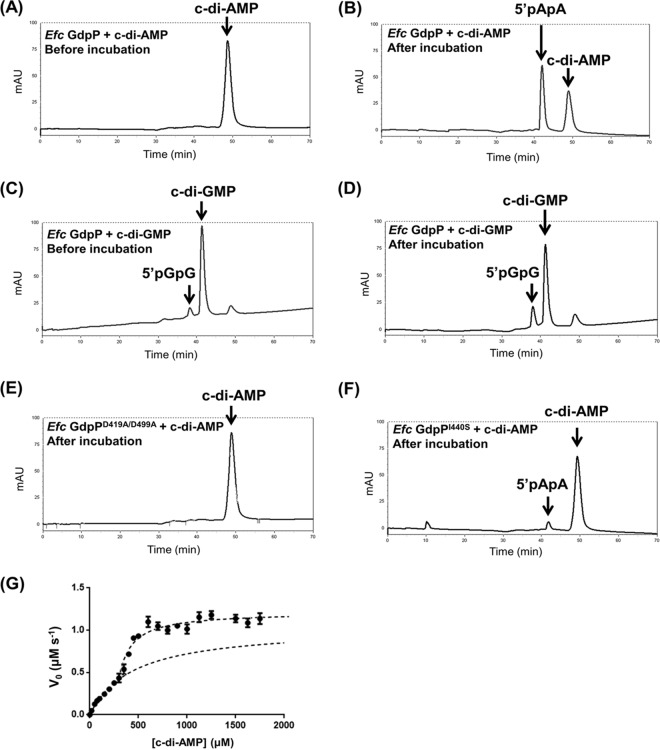

On the basis of primary sequence homology, we hypothesized that the gene product of unknown function previously annotated as E. faecalis YybT was a potential cyclic dinucleotide phosphodiesterase of the GdpP family (E. faecalis GdpP) (3, 4, 24). E. faecalis GdpP is a multidomain protein containing two putative N-terminal transmembrane helices, a Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain, a GGDEF domain, and a DHH domain with a DHHA1 subdomain (Fig. 2A) (24). The PAS domain is a putative signal input module and is frequently involved in signal transduction in orthologous systems (see Discussion; also see Fig. S1 and Text S2 in the supplemental material) (29). The GGDEF domain often has diguanylate cyclase activity (discussed below) (30). Thus, on the basis of homology (see Fig. S2), we postulated that the putative DHH/DHHA1 domain of E. faecalis GdpP would have cyclic dinucleotide phosphodiesterase activity (3, 4, 24). To test this hypothesis, E. faecalis GdpP and the DHH/DHHA1 domain (residues 309 to 658, referred to as GdpP309-658) were characterized in vitro. Purified wild-type protein was incubated with c-di-AMP or c-di-GMP, and the products were analyzed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). As shown in Fig. 3A and B, incubation of GdpP with c-di-AMP resulted in a decrease of the cyclic dinucleotide peak and the formation of a new product corresponding to linear dinucleotide 5′pApA without generating AMP or 3′pApA. This result indicates that E. faecalis GdpP hydrolyzes c-di-AMP solely into 5′pApA and is consistent with the activity of B. subtilis GdpP measured previously (24). We also determined the phosphodiesterase activity of GdpP toward the cleavage of c-di-GMP. On the basis of HPLC analysis, c-di-GMP is not the physiological substrate of E. faecalis GdpP, although it has a weak ability to hydrolyze c-di-GMP to 5′pGpG (Fig. 3C and D).

FIG 2.

Domain organization and predicted structure of E. faecalis GdpP. E. faecalis GdpP is a multidomain protein containing two putative N-terminal transmembrane helices (TM1 and TM2), a PAS domain, a GGDEF domain, and a DHH domain with a DHHA1 subdomain. (A) The DHH/DHHA1 domain contains the c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase active site, while the GGDEF domain has a low level of ATPase activity. The daptomycin adaptive mutation I440S is in the DHH domain. (B) Predicted structure model of the E. faecalis GdpP DHH/DHHA1 domain indicating the presumptive phosphodiesterase active site and proximal position of I440S. Two Mn2+ ions are shown as magenta spheres. Asp residues 419 and 499 are blue, and Ile 440 is orange. The structural model was built with the Phyre2 server (40). The Mn2+ positions were predicted by alignment with M. tuberculosis phosphodiesterase Rv2837c (PDB accession no. 5CET) (32).

FIG 3.

E. faecalis GdpP has phosphodiesterase activity with specificity for c-di-AMP. (A to F) Reverse-phase HPLC analysis of products from incubation of wild-type E. faecalis (Efc) GdpP and variants with cyclic dinucleotides at 28°C for 2 h with 100 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 20 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM MnCl2. Shown are wild-type E. faecalis GdpP and c-di-AMP before (A) and after (B) incubation, wild-type E. faecalis GdpP with c-di-GMP before (C) and after (D) incubation, E. faecalis GdpPD419A/D499A after incubation with c-di-AMP (E), and E. faecalis GdpPI440S after incubation with c-di-AMP (F). (G) Steady-state kinetic analysis of E. faecalis GdpP DHH/DHHA1 domain (E. faecalis GdpP309-658) phosphodiesterase activity at 37°C. The reaction mixture contained 2.5 μM E. faecalis GdpP309-658, 50 mM CHES (pH 9.2), 20 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MnCl2, and 1 mM fluorinated octyl maltoside. mAU, milliabsorbance units; V0, reaction velocity.

Once the specificity for c-di-AMP was established, we quantitated the phosphodiesterase activity of the DHH/DHHA1 domain alone (E. faecalis GdpP309-658) and the full-length protein with the coralyne activity assay fluorescence turn-on assay (31). The activity of the full-length protein was weak (see Fig. S3D), and saturating conditions of c-di-AMP were not practical to establish, while activity by E. faecalis GdpP309-658 was ∼13 times as high, allowing us to reach saturating conditions and establish kinetic parameters. The kinetic data for GdpP309-658 were clearly multiphasic and could be fitted to two phases to produce two Kms extending over the conditions ranging from 0 to 300 and from 300 to 1,750 μM c-di-AMP. The Michaelis-Menten reaction rate constants calculated separately for the two phases produce very similar kcat values but a 3.3-fold change in the Km (Km1 = 443.6 ± 97.53 μM, kcat1 = 0.42 ± 0.16 s−1, Km2 = 132.6 ± 20.05 μM, kcat2 = 0.49 ± 0.01 s−1) (Fig. 3G; see Fig. S3). GdpP309-658 was difficult to purify, with a strong tendency to aggregate and adsorb nonspecifically. Upon purification, we found that the detergent fluorinated octyl maltoside at 1 mM could reduce aggregation and produced protein that was twice as active (see Fig. S3). Taken together, the poor behavior of the protein during purification and the importance of fluorinated octyl maltoside to increase activity suggest that the multiphasic kinetics we observed may reflect the tendency of the protein to adsorb/aggregate as a less active population and that increasing the substrate concentration to >300 μM mitigated that effect to increase activity. Alternatively, a conformational change within the DHH/DHHA1 domain could occur at higher c-di-AMP concentrations and be a physiological feature of GdpP. Thus, when toxic levels of c-di-AMP are reached, GdpP phosphodiesterase activity may increase.

Aspartates 419 and 499 are essential to E. faecalis GdpP phosphodiesterase activity.

On the basis of a comparison of the E. faecalis GdpP sequence with those of others phosphodiesterases, Asp residues 419 and 499 are predicted to be ligands for the metal ion binding site required for phosphodiesterase activity (Fig. 2B; see Fig. S2) (24). To test whether Asp 419 and Asp 499 are required for phosphodiesterase activity, we generated the double mutant E. faecalis GdpPD419A/D499A. As expected, no activity was detected after the incubation of E. faecalis GdpPD419A/D499A with c-di-AMP (Fig. 3E). These results indicate that alignment of the primary sequences of E. faecalis GdpP with those of other members of the DHH protein family of phosphodiesterases has correctly identified residues essential to activity and support our conclusion that E. faecalis GdpP is a bone fide cyclic dinucleotide phosphodiesterase.

Adaptive mutant protein GdpPI440S, which correlates with daptomycin resistance in E. faecalis S613, strongly decreases phosphodiesterase activity.

In E. faecalis GdpP, the adaptive mutation I440S is located in the putative DHH domain (Fig. 2A) and is proximal to the predicted substrate binding site (Fig. 2B) (32). To elucidate how the adaptive mutation may facilitate daptomycin resistance, we determined the phosphodiesterase activity of E. faecalis GdpPI440S toward its potential physiological substrate c-di-AMP. As shown in Fig. 3F, incubation of c-di-AMP with GdpPI440S showed an 11-fold reduction in the ability to hydrolyze c-di-AMP to 5′pApA. Thus, gdpPI440S was identified in the daptomycin adaptive isolates (19) and may lead to c-di-AMP accumulation in these strains, suggesting that high intracellular c-di-AMP levels are important for E. faecalis physiology during daptomycin-induced membrane stress.

E. faecalis GdpP has phosphodiesterase activity in vivo.

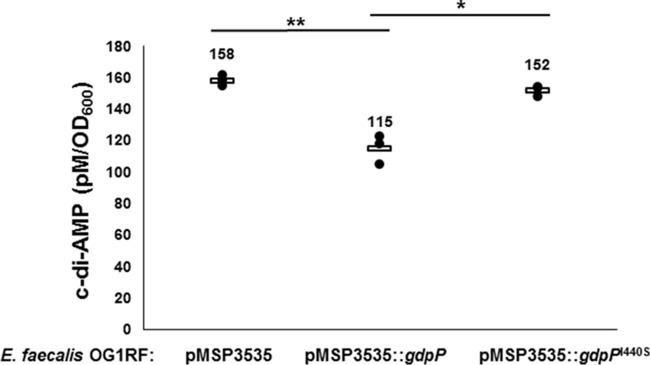

To further test whether E. faecalis GdpP has phosphodiesterase activity in vivo, the gene coding wild-type E. faecalis GdpP was subcloned into nisin-inducible vector pMSP3535 (33) and transformed into E. faecalis OG1RF. As shown in Fig. 4 and Table 1, overexpression of E. faecalis GdpP decreased cellular c-di-AMP levels by about 27% compared with the empty plasmid. The decreased c-di-AMP levels in cells expressing E. faecalis GdpP from plasmid pMSP3535 were statistically significantly different from those of the control strain (P = 0.008). We expected that expression of the E. faecalis GdpPI440S mutant protein from plasmid pMSP335 would lead to restored levels of c-di-AMP. While there was a very modest decrease in c-di-AMP levels, it was not statistically significant (P = 0.078). There could be a number of reasons for the inability of E. faecalis GdpPI440S to fully restore c-di-AMP levels. First, the mutation I440S decreases the phosphodiesterase activity by around 11-fold but does not completely abolish it. Second, since E. faecalis GdpPI440S is being expressed along with the genomic copies of wild-type GdpP in addition to the c-di-AMP synthesis and regulatory genes, the net effect of E. faecalis GdpPI440S might be compensated for by the homeostatic machinery of the cell. We observed a slight c-di-AMP level increase in E. faecalis OG1RF::pMSP3535 compared with that of E. faecalis OG1RF (158 ± 3 versus 112 ± 47 pM/OD600 [P = 0.225]; see Table 1 and Fig. 1A and 4 for details), which may be caused by the addition of nisin, since higher c-di-AMP levels were also detected when E. faecalis OG1RF::pMSP3535 was cultured with nisin versus in its absence (data not shown). Together, our data strongly suggest that E. faecalis GdpP has phosphodiesterase activity in vivo and can regulate intracellular c-di-AMP levels.

FIG 4.

Expression of the c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase E. faecalis GdpP in trans leads to reduced c-di-AMP levels in vivo. Intracellular concentrations of c-di-AMP in E. faecalis OG1RF during the expression of E. faecalis GdpP or E. faecalis GdpPI440S. Expression of E. faecalis GdpP leads to a statistically significant decrease in the c-di-AMP level (∼27%). Expression of E. faecalis GdpPI440S does not lead to a significant change in c-di-AMP. Three independent biological measurements of each strain were made. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

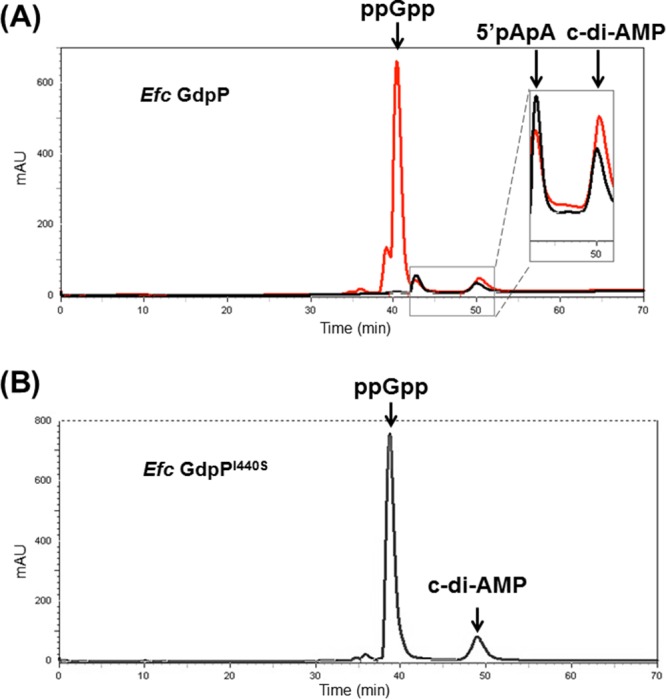

E. faecalis GdpPI440S is more sensitive to inhibition by ppGpp in vitro.

Several studies on homologs to E. faecalis GdpP have reported that ppGpp can inhibit GdpP phosphodiesterase activity (24, 34). ppGpp is a stringent response signaling molecule and accumulates in some bacteria during nutrient starvation (35). In B. subtilis, ppGpp binds to B. subtilis GdpP and inhibits phosphodiesterase activity (referred to as YybT in reference 24). To determine whether ppGpp is a direct inhibitor of E. faecalis GdpP, 1 mM ppGpp was incubated with 10 μM E. faecalis GdpP and 100 μM c-di-AMP. Figure 5A shows that ppGpp inhibited E. faecalis GdpP phosphodiesterase activity very modestly and did not completely abolish it, even though the molar ratio of c-di-AMP to ppGpp was 1:10. Our data suggest that ppGpp is a very weak inhibitor of E. faecalis GdpP phosphodiesterase activity in vitro. When 1 mM ppGpp was added to the reaction system of 10 μM E. faecalis GdpPI440S and 100 μM c-di-AMP, no c-di-AMP was hydrolyzed to 5′pApA after incubation for 2 h (Fig. 5B). Our data indicate that the residual phosphodiesterase activity of E. faecalis GdpPI440S can be inhibited by ppGpp in vitro, which suggests that E. faecalis GdpPI440S could be more sensitive to ppGpp than wild-type E. faecalis GdpP is in vivo.

FIG 5.

ppGpp is able to modestly inhibit E. faecalis GdpP phosphodiesterase activity. (A) Reverse-phase HPLC analysis of products from incubation of wild-type E. faecalis (Efc) GdpP and c-di-AMP with (red) and without (black) 1 mM ppGpp after incubation for 2 h at 28°C. (B) E. faecalis GdpPI440S with c-di-AMP and ppGpp after 2 h of incubation at 28°C showing no significant 5′pApA production.

E. faecalis GdpP has ATPase activity in vitro.

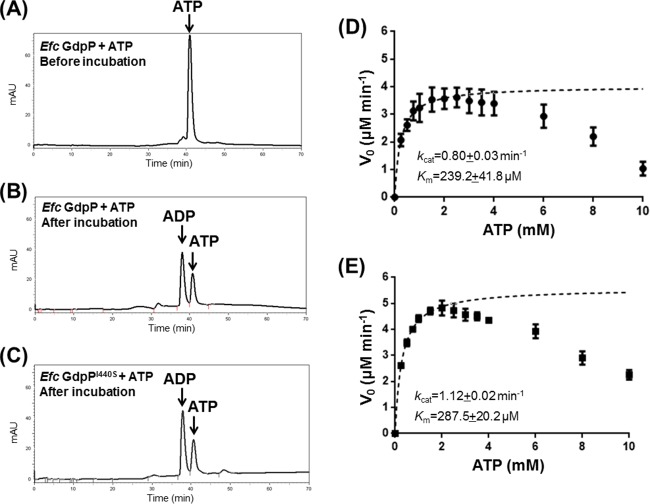

E. faecalis GdpP has a putative GGDEF domain, which is unusual, as the previously described GdpP family proteins typically lack the conserved GGD(E)EF motif (4, 5, 24, 29). The GGDEF domain in B. subtilis GdpP has only very weak ATPase activity (referred to as YybT in reference 24). Proteins containing GGDEF domains in Gram-negative bacteria often have diguanylate cyclase activity (30). Primary sequence alignment indicated that E. faecalis GdpP (similar to B. subtilis GdpP) contains a modified GGDEF domain with a highly divergent amino acid sequence (see Fig. S4). The GGDEF domain in B. subtilis GdpP can bind ATP and slowly convert it to ADP (24). To test whether E. faecalis GdpP exhibits ATPase activity, we incubated 100 μM ATP with 10 μM E. faecalis GdpP and analyzed the products by reverse-phase HPLC. The chromatographic analysis revealed that E. faecalis GdpP could hydrolyze ATP, leading to the formation of ADP after incubation (Fig. 6A and B). The ATPase activity of E. faecalis GdpP had a kcat of 0.80 ± 0.03 min−1 and a Km of 239.2 ± 41.8 μM (Fig. 6D), while the B. subtilis GdpP homolog had a similar kcat value but a markedly lower Km (kcat = 0.59 ± 0.03 min−1, Km = 0.90 ± 0.12 mM) (24). To assess whether the mutation of Ile 440 to Ser in the DHH domain could affect ATPase activity in the GGDEF domain, we measured the ATPase activity of E. faecalis GdpPI440S. The ATPase activity of E. faecalis GdpPI440S was comparable to that of wild-type GdpP (Fig. 6C), with a kcat of 1.12 ± 0.02 min−1 and a Km of 287.5 ± 20.2 μM (Fig. 6E). Thus, it appears that the I440S mutation in the DHH domain does not affect the ATPase activity in the GGDEF domain (P = 0.880).

FIG 6.

E. faecalis GdpP and GdpPI440S have comparable ATPase activities. Shown are results of reverse-phase HPLC analysis of ATP and wild-type E. faecalis (Efc) GdpP before incubation (A), ATP and wild-type E. faecalis GdpP after 2 h of incubation at 25°C (B), and ATP and E. faecalis GdpPI440S after 2 h of incubation at 25°C (C). (D) ATPase activity measurement of 5 μM E. faecalis GdpP at 28°C. (E) ATPase activity measurement of 5 μM E. faecalis GdpPI440S at 28°C. The reaction buffer contained 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 1 mM MgCl2. mAU, milliabsorbance units; V0, reaction velocity.

The weak ATPase activity of GdpP required us to use up to 2 mM ATP to provide sufficient data for our analysis. When performing the ATPase studies, we observed unexpected substrate inhibition of the ATPase activity. Interestingly, inhibition starts at about 2.5 mM ATP, which is in the range of its intracellular concentration (about 1 to 10 mM) (36). To confirm that the inhibition was not caused by the reagents used in the colorimetric ATPase assay, we incubated 10 μM E. faecalis GdpP with 2 and 6 mM ATP at 28°C, respectively, and analyzed the products directly by reverse-phase HPLC (see Fig. S5). Our data suggest that in vitro substrate inhibition could be biologically relevant and led us to suspect that the local cellular ATP concentration could alter E. faecalis GdpP ATPase activity. Incubation of GdpP with ATP or GTP did not produce either c-di-AMP or c-di-GMP, and thus it appears that the GGDEF domain is not a c-di-AMP or c-di-GMP synthase in vitro.

Mutations in the LiaFSR signaling pathway can affect intracellular c-di-AMP levels.

During adaptation to daptomycin, the first step toward resistance was a family of mutations that, while in different genes, upregulated the LiaFSR membrane stress response pathway (19, 37). In two of the evolutionary trajectories leading to daptomycin resistance, an Ile-to-Ser substitution at position 440, was observed in GdpP (19). Interestingly, GdpPI440S was always found in association with a LiaR substitution (LiaRD191N), suggesting an epistatic link between changes in LiaFSR signaling and GdpP (19). Since LiaR is the response regulator of the LiaFSR membrane stress response system (21), we investigated the possibility that the LiaFSR pathway regulates the levels of c-di-AMP.

To test whether LiaFSR leads to changes in intracellular c-di-AMP regulation, we initially used a strain in which we had generated a nonpolar deletion of liaR in E. faecalis. Cell extracts from such a mutant (E. faecalis OG1RF_ΔliaR, Table 1) were tested for c-di-AMP levels. Of note, the liaR deletion removes the response regulator of the LiaFSR pathway, effectively “shutting off” the LiaFSR system. Deletion of liaR (E. faecalis OG1RF_ΔliaR) upregulated the levels of c-di-AMP to 351 ± 94 pM/OD600 (Fig. 1A and Table 1), a >3-fold increase over wild-type E. faecalis OG1RF (P = 0.030). When liaR expression was restored in cis in E. faecalis OG1RF_ΔliaR (E. faecalis OG1RF_ΔliaR::liaR, Table 1), cellular c-di-AMP levels returned to the levels observed in wild-type E. faecalis OG1RF (140 ± 29 pM/OD600, P = 0.436, Fig. 1A and Table 1). These results suggest that decreases in LiaFSR signaling lead to increases in intracellular c-di-AMP levels.

To demonstrate that changes in LiaFSR signaling lead to changes in c-di-AMP more broadly, we measured the c-di-AMP levels in nonpolar liaR deletion mutants of E. faecium strains HOU503F and R497F (E. faecium HOU503F_ΔliaR and R497F_ΔliaR, Table 1) which are tolerant of and resistant to daptomycin (27). As observed with E. faecalis, deletion of liaR in E. faecium HOU503F_ΔliaR and R497F_ΔliaR showed modest increases in c-di-AMP levels compared to E. faecium HOU503F and R497F (622 ± 104 pM/OD600 versus 542 ± 133 pM/OD600 and 736 ± 186 pM/OD600 versus 549 ± 150 pM/OD600, Fig. 1B and Table 1) but the increases were not statistically significant (P = 0.250 and 0.461). It is interesting that the inactivation of the LiaFSR pathway in E. faecium does not increase c-di-AMP concentrations to the same extent as observed in E. faecalis. The basal level of c-di-AMP in E. faecium HOU503F and R497F was much greater than that in E. faecalis OG1RF or S613, and thus there are substantial differences in the basal c-di-AMP pools of these related organisms. cis complementation with liaR decreased the intracellular c-di-AMP levels of E. faecium HOU503F_ΔliaR::liaR and R497F_ΔliaR::liaR to 505 ± 54 and 525 ± 134 pM/OD600, respectively, similar to the c-di-AMP levels in wild-type strains (Fig. 1B and Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Cyclic dinucleotide signaling in bacteria is widespread and is linked to a variety of regulatory responses, including DNA integrity reporting (28), cell wall biosynthesis (4, 9), potassium homeostasis (10), and biofilm formation (4). Experimental evolution of a polymorphic population of E. faecalis S613 to daptomycin resistance with a continuous-evolution bioreactor identified a point mutation (yybTI440S) in a gene of unknown function initially named yybT (19). On the basis of primary sequence identity, we postulated that YybT might, in fact, be a cyclic dinucleotide phosphodiesterase, and on the basis of our studies, we have established phosphodiesterase activity consistent with its classification as a member of the GdpP family. Therefore, we have changed the name to GdpP. As c-di-AMP signaling in enterococci had not been established, we first tested if c-di-AMP was present at levels consistent with a role in in vivo signaling (from 44 to 1,133 pM/OD600, Fig. 1). Having established that c-di-AMP was present in vivo, we went on to confirm the role of the novel GdpP in c-di-AMP homeostasis.

As shown in Fig. 2, GdpP is composed of three distinct domains. We purified and characterized full-length E. faecalis GdpP, as well as the DHH/DHHA1 domain (E. faecalis GdpP309-658). Our results showed that E. faecalis GdpP is indeed a c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase with a strong preference for c-di-AMP over c-di-GMP. E. faecalis GdpPI440S shows little phosphodiesterase activity, and as expected, strains encoding E. faecalis GdpPI440S have increased c-di-AMP levels in vivo. Our results showed that expression of E. faecalis GdpP from the inducible vector pMSP3535 in wild-type E. faecalis OG1RF decreased the cellular c-di-AMP level by 27% (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Although we could demonstrate weak ATPase activity in the GGDEF domain and c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase activity in the DHH/DHHA1 domain, we were unable to identify the in vivo function of either domain. The PAS domain could be a critical regulator of the activities of the GGDEF and DHH/DHHA1 domains in vivo. For example, the c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase activity of the DHH/DHHA1 domain alone (GdpP309-658) is ∼13 times as high as that of the full-length protein, suggesting that under specific conditions or stimuli in vivo, the kinetic rates of the activities within the GdpP domains may be quite variable and well regulated. Undoubtedly, each of the GdpP domains has a relevant activity or role in vivo. A study of S. aureus GdpP showed that two mutations in its GGDEF domain could increase resistance to the antibiotics vancomycin and oxacillin and that complementation with an S. aureus GdpP N-terminal truncation with an inactive DHH domain could restore antibiotic susceptibility (38). Together, these observations suggest that the E. faecalis GdpP GGDEF domain has additional activities in vivo beyond weak ATP hydrolysis. Recently, the GGDEF domains from Deltaproteobacteria were also reported to have a hybrid dinucleotide cyclase activity and can synthesize c-di-AMP, c-di-GMP, and cyclic AMP-GMP (3′,3′-cGAMP) (39). The functional role of the PAS and GGDEF domains is the subject of ongoing investigation.

On the basis of sequence homology, E. faecalis has only one gene encoding a potential c-di-AMP synthase A (CdaA, also referred as YbbP) (2). Our finding of a robust c-di-AMP pool in E. faecalis suggests that E. faecalis CdaA is active in vivo. E. faecalis has two potential genes encoding c-di-AMP phosphodiesterases, gdpP and pgpH (8). L. monocytogenes PgpH is a membrane protein that can hydrolyze c-di-AMP to 5′pApA via a His-Asp (HD) domain (8). A study of L. monocytogenes c-di-AMP phosphodiesterases showed that DHH/DHHA1 family phosphodiesterases are more important than HD family phosphodiesterases for bacterial virulence and intracellular growth (8), which may be the reason that we did not observe mutations in PgpH in the clinical or experimental evolution data for enterococci.

Since GdpPI440S was found to be associated with changes within the LiaFSR pathway, we tested the effect of the mutations in the LiaFSR pathway upon in vivo c-di-AMP levels. We found that the deletion of liaR (E. faecalis OG1RF_ΔliaR) led to increased c-di-AMP levels (Table 1 and Fig. 1). While it is tempting to link c-di-AMP levels to daptomycin resistance, the nature of this association is unclear. Nonetheless, we observed a significant increase in c-di-AMP levels in a nonpolar liaR deletion of E. faecalis OG1RF (Fig. 1A and Table 1). However, quantitative PCR of the potential target genes cdaA, gdpP, and pgpH did not show significant changes in transcription (see Fig. S6), suggesting that the effects of mutations in LiaFSR signaling on cellular c-di-AMP levels are indirect. It is possible that cellular c-di-AMP pools will also respond dynamically through several stress regulons, including LiaFSR. In addition, other as-yet-unidentified regulatory mechanisms may also be involved in the system. For example, there may be another unknown c-di-AMP synthase in enterococci that responds to LiaFSR activation. Additionally, an unknown cofactor or stress may switch the function of GdpP from c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase (DHH/DHHA1 domain activity) to c-di-AMP synthase (putative GGDEF activity) (39). While we were unable to demonstrate that the E. faecalis GdpP GGDEF domain has c-di-AMP synthase activity, GGDEF domains of other proteins do have demonstrated synthase activity (39). How the PAS domain of GdpP might regulate the known DHH/DHHA1 domain phosphodiesterase activity, as well as the potential cryptic activities of the GGDEF domain, remains unknown. Although the complete signaling mechanism by which LiaFSR regulates c-di-AMP level remains to be fully elucidated, it is evident that membrane damage is faithfully transduced and converted into altered levels of c-di-AMP.

In summary, we show that c-di-AMP is an important second messenger in enterococci and that a novel GdpP phosphodiesterase previously associated with daptomycin resistance is important for the modulation of c-di-AMP in response to cell membrane damage caused by the antibiotic. Moreover, LiaFSR seems to influence c-di-AMP pools in vivo. Our findings suggest that c-di-AMP signaling constitutes a key aspect of the membrane damage response with important consequences for our understanding of how enterococci respond to daptomycin and other cationic antimicrobial peptides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth media.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. faecalis OG1RF harboring pMSP3535 and recombinant plasmids was grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) supplied with 10 μg/ml erythromycin and nisin as described in reference 33. Other E. faecalis strains were grown in LBHI broth (80% lysogeny broth [LB] and 20% brain heart infusion [BHI]) as described in reference 19. E. faecium HOU503 was grown in LBHI broth. Other E. faecium strains were grown in BHI. When daptomycin was added, 50 mg/liter CaCl2 was supplied to the medium (19). (see Text S1 for details).

Measurement of intracellular c-di-AMP by competitive ELISA.

The c-di-AMP competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) protocols of Underwood et al. (26) were optimized for the measurement of intracellular c-di-AMP concentrations in E. faecalis and E. faecium (see Text S1 for details).

Plasmid construction.

E. faecalis gdpP and subdomains were amplified by PCR from E. faecalis S613 with specific primers (see Table S1) with PfuUltra II DNA polymerase. PCR products were digested with appropriate restriction endonucleases and cloned into pET-28a (Novagen) for expression in E. coli BL21 or into pMSP3535 (33) for expression in E. faecalis OG1RF. Plasmids for the expression of E. faecalis GdpPI440S and GdpPD419A/D499A were generated by site-directed mutagenesis (see Table S1).

Expression of E. faecalis GdpP and GdpPI440S in E. faecalis OG1RF.

E. faecalis OG1RF strains with recombinant plasmids were grown in BHI with 10 μg/ml erythromycin. Overnight cultures of E. faecalis OG1RF with recombinant plasmids were diluted 1:100 to BHI with 10 μg/ml erythromycin on the second day, and 20 ng/ml nisin was added when the OD600 was ∼0.5. Cultures were incubated at 37°C shaken at 225 rpm overnight. On the third day, the overnight cultures were rediluted in BHI with 10 μg/ml erythromycin and 20 ng/ml nisin. Cells were harvested after the OD600 reached 1.5 (late exponential phase of E. faecalis OG1RF strains with plasmid pMSP3535) for c-di-AMP measurements.

Expression and purification of E. faecalis GdpP.

Overnight cultures of E. coli BL21 carrying E. faecalis GdpP expression vector pET28a-E. faecalis_GdpP was diluted 1:100 in 8 liters of 2× YT medium supplemented with 50 mg/liter kanamycin and shaken at 37°C until the OD600 reached 0.6 to 0.7. Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 0.5 mM was then added to induce protein expression. Cultures were shaken at 16°C for 20 h before being harvested by centrifugation. Cells were resuspended in Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) buffer A (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 20 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 5% glycerol [vol/vol]) and opened by sonication on ice with three cycles of 2 min on and 3 min off at output 6/50% duty cycle. Supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 24,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C. The protein was purified initially with a gravity Ni-NTA column and step eluted with Ni-NTA buffer B (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 200 mM imidazole, 440 mM NaCl, 9 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.2 mM PMSF, 5% glycerol [vol/vol]). The fractions containing target protein were collected and dialyzed overnight at 4°C against gel filtration buffer (25 mM N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid [CHES, pH 8.6], 200 mM NaCl). Protein was subsequently concentrated and further purified on a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 gel filtration column. Fractions containing target protein were collected. Fresh protein should be used for the following experiments, as storage at −80°C reduces activity.

Product analysis of GdpP reactions by HPLC.

For ATPase activity, 10 μM protein and 100 μM ATP were incubated at 28°C for 2 h in a reaction buffer containing 40 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 10 mM MgCl2. For phosphodiesterase activity, 10 μM protein was incubated with 100 μM c-di-AMP or c-di-GMP at 28°C for 2 h in a reaction buffer containing 100 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 20 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM MnCl2. ppGpp at 1 mM was added to the reaction buffer in experiments to estimate ppGpp inhibition of GdpP phosphodiesterase activity. Reactions were stopped, and protein was precipitated by the addition of trifluoroacetic acid to a 1% (vol/vol) final concentration and incubated on ice for 15 min. Precipitants were removed by centrifugation. A total of 10 μl of each nucleotide standard or sample was injected into a reverse-phase C18 column (Hamilton catalog no. 79674) and eluted with a gradient of 0 to 100% (buffer A was 0.1 M KH2PO4 and 4 mM tetrabutylammonium bromide [pH 6.0], and buffer B was 60% buffer A and 40% methanol [pH 5.5]).

Kinetic measurement of phosphodiesterase activity.

The protocols of the coralyne fluorescence turn-on assay of Zhou et al. (31) were optimized to determine the enzymatic activity of E. faecalis GdpP309-658 phosphodiesterase toward c-di-AMP (see Text S1 for details).

Kinetic measurement of ATPase activity.

The steady-state kinetics of ATPase activity were determined with the EnzChek Phosphate Assay kit (Life Technologies) by measuring the release of inorganic phosphate hydrolyzed from ATP. The reactions were set up in a 96-well plate and monitored with a Bio-Rad plate reader.

Structural modeling.

A structural model of the E. faecalis GdpP DHH-DHHA1 domain was built with the Phyre2 server (40). The Mn2+ ion positions were predicted by alignment with Mycobacterium tuberculosis phosphodiesterase Rv2837c (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession no. 5CET) (32).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants (R01AI080714 to Y.S. and R01-AI093749, R21-AI114961, and R21/R33 AI121519 to C.A.A.) and a China Scholarship Council scholarship (2011620008 to X.W.).

Cesar Arias is on the speaker's bureau for Forest, Theravance, Pfizer, Astra-Zeneca, Cubist, The Medicines Company, and Novartis. He is also consulting for Theravance, Cubist, and Bayer and is a grant investigator for Theravance and a scientific advisor (review panel or advisor committee) for Bayer.

X.W., M.D., C.A.A., and Y.S. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. X.W., J.R., and D.P. performed the experiments. C.A.A., M.D., and Y.S. edited the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01422-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Römling U. 2008. Great times for small molecules: c-di-AMP, a second messenger candidate in bacteria and archaea. Sci Signal 1:pe39. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.133pe39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehne FM, Gunka K, Eilers H, Herzberg C, Kaever V, Stülke J. 2013. Cyclic di-AMP homeostasis in Bacillus subtilis: both lack and high level accumulation of the nucleotide are detrimental for cell growth. J Biol Chem 288:2004–2017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.395491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witte CE, Whiteley AT, Burke TP, Sauer J-D, Portnoy DA, Woodward JJ. 2013. Cyclic di-AMP is critical for Listeria monocytogenes growth, cell wall homeostasis, and establishment of infection. mBio 4:e00282-3. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00282-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corrigan RM, Abbott JC, Burhenne H, Kaever V, Gründling A. 2011. c-di-AMP is a new second messenger in Staphylococcus aureus with a role in controlling cell size and envelope stress. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002217. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho KH, Kang SO. 2013. Streptococcus pyogenes c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase, GdpP, influences SpeB processing and virulence. PLoS One 8:e69425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bai Y, Yang J, Eisele LE, Underwood AJ, Koestler BJ, Waters CM, Metzger DW, Bai G. 2013. Two DHH subfamily 1 proteins in Streptococcus pneumoniae possess cyclic di-AMP phosphodiesterase activity and affect bacterial growth and virulence. J Bacteriol 195:5123–5132. doi: 10.1128/JB.00769-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gundlach J, Mehne FMP, Herzberg C, Kampf J, Valerius O, Kaever V, Stülke J. 2015. An essential poison: synthesis and degradation of cyclic di-AMP in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 197:3265–3274. doi: 10.1128/JB.00564-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huynh TN, Luo S, Pensinger D, Sauer J-D, Tong L, Woodward JJ. 2015. An HD-domain phosphodiesterase mediates cooperative hydrolysis of c-di-AMP to affect bacterial growth and virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E747–E756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416485112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Commichau FM, Dickmanns A, Gundlach J, Ficner R, Stülke J. 2015. A jack of all trades: the multiple roles of the unique essential second messenger cyclic di-AMP. Mol Microbiol 97:189–204. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corrigan RM, Campeotto I, Jeganathan T, Roelofs KG, Lee VT, Gründling A. 2013. Systematic identification of conserved bacterial c-di-AMP receptor proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:9084–9089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300595110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo Y, Helmann JD. 2012. A σD-dependent antisense transcript modulates expression of the cyclic-di-AMP hydrolase GdpP in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 158:2732–2741. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.062174-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith WM, Pham TH, Lei L, Dou J, Soomro AH, Beatson SA, Dykes GA, Turner MS. 2012. Heat resistance and salt hypersensitivity in Lactococcus lactis due to spontaneous mutation of llmg_1816 (gdpP) induced by high-temperature growth. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:7753–7759. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02316-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rismondo J, Gibhardt J, Rosenberg J, Kaever V, Halbedel S, Commichau FM. 2015. Phenotypes associated with the essential diadenylate cyclase CdaA and its potential regulator CdaR in the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol 198:416–426. doi: 10.1128/JB.00845-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arias CA, Panesso D, McGrath DM, Qin X, Mojica MF, Miller C, Diaz L, Tran TT, Rincon S, Barbu EM, Reyes J, Roh JH, Lobos E, Sodergren E, Pasqualini R, Arap W, Quinn JP, Shamoo Y, Murray BE, Weinstock GM. 2011. Genetic basis for in vivo daptomycin resistance in enterococci. N Engl J Med 365:892–900. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arias CA, Murray BE. 2012. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:266–278. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC. 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arias CA, Murray BE. 2008. Emergence and management of drug-resistant enterococcal infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 6:637–655. doi: 10.1586/14787210.6.5.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung D, Rozek A, Okon M, Hancock RE. 2004. Structural transitions as determinants of the action of the calcium-dependent antibiotic daptomycin. Chem Biol 11:949–957. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller C, Kong J, Tran TT, Arias CA, Saxer G, Shamoo Y. 2013. Adaptation of Enterococcus faecalis to daptomycin reveals an ordered progression to resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5373–5383. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01473-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer KL, Daniel A, Hardy C, Silverman J, Gilmore MS. 2011. Genetic basis for daptomycin resistance in enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3345–3356. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00207-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf D, Kalamorz F, Wecke T, Juszczak A, Mäder U, Homuth G, Jordan S, Kirstein J, Hoppert M, Voigt B. 2010. In-depth profiling of the LiaR response of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 192:4680–4693. doi: 10.1128/JB.00543-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrecke K, Jordan S, Mascher T. 2013. Stoichiometry and perturbation studies of the LiaFSR system of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 87:769–788. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davlieva M, Shi Y, Leonard PG, Johnson TA, Zianni MR, Arias CA, Ladbury JE, Shamoo Y. 2015. A variable DNA recognition site organization establishes the LiaR-mediated cell envelope stress response of enterococci to daptomycin. Nucleic Acids Res 43:4758–4773. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao F, See RY, Zhang D, Toh DC, Ji Q, Liang Z-X. 2010. YybT is a signaling protein that contains a cyclic dinucleotide phosphodiesterase domain and a GGDEF domain with ATPase activity. J Biol Chem 285:473–482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bourgogne A, Garsin DA, Qin X, Singh KV, Sillanpaa J, Yerrapragada S, Ding Y, Dugan-Rocha S, Buhay C, Shen H, Chen G, Williams G, Muzny D, Maadani A, Fox KA, Gioia J, Chen L, Shang Y, Arias CA, Nallapareddy SR, Zhao M, Prakash VP, Chowdhury S, Jiang H, Gibbs RA, Murray BE, Highlander SK, Weinstock GM. 2008. Large scale variation in Enterococcus faecalis illustrated by the genome analysis of strain OG1RF. Genome Biol 9:R110. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-7-r110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Underwood AJ, Zhang Y, Metzger DW, Bai G. 2014. Detection of cyclic di-AMP using a competitive ELISA with a unique pneumococcal cyclic di-AMP binding protein. J Microbiol Methods 107:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panesso D, Reyes J, Gaston EP, Deal M, Londoño A, Nigo M, Munita JM, Miller WR, Shamoo Y, Tran TT, Arias CA. 2015. Deletion of liaR reverses daptomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium independent of the genetic background. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:7327–7334. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01073-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oppenheimer-Shaanan Y, Wexselblatt E, Katzhendler J, Yavin E, Ben-Yehuda S. 2011. c-di-AMP reports DNA integrity during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO Rep 12:594–601. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao F, Ji Q, Soehano I, Liang Z-X. 2011. Unusual heme-binding PAS domain from YybT family proteins. J Bacteriol 193:1543–1551. doi: 10.1128/JB.01364-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryjenkov DA, Tarutina M, Moskvin OV, Gomelsky M. 2005. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J Bacteriol 187:1792–1798. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1792-1798.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou J, Sayre DA, Zheng Y, Szmacinski H, Sintim HO. 2014. Unexpected complex formation between coralyne and cyclic diadenosine monophosphate providing a simple fluorescent turn-on assay to detect this bacterial second messenger. Anal Chem 86:2412–2420. doi: 10.1021/ac403203x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He Q, Wang F, Liu S, Zhu D, Cong H, Gao F, Li B, Wang H, Lin Z, Liao J, Gu L. 2016. Structural and biochemical insight into the mechanism of Rv2837c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a c-di-NMP phosphodiesterase. J Biol Chem 291:3668–3681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.699801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryan EM, Bae T, Kleerebezem M, Dunny GM. 2000. Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in Gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44:183–190. doi: 10.1006/plas.2000.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corrigan RM, Bowman L, Willis AR, Kaever V, Gründling A. 2015. Cross-talk between two nucleotide-signaling pathways in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem 290:5826–5839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.598300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalia D, Merey G, Nakayama S, Zheng Y, Zhou J, Luo Y, Guo M, Roembke BT, Sintim HO. 2013. Nucleotide, c-di-GMP, c-di-AMP, cGMP, cAMP, (p)ppGpp signaling in bacteria and implications in pathogenesis. Chem Soc Rev 42:305–341. doi: 10.1039/C2CS35206K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yaginuma H, Kawai S, Tabata KV, Tomiyama K, Kakizuka A, Komatsuzaki T, Noji H, Imamura H. 2014. Diversity in ATP concentrations in a single bacterial cell population revealed by quantitative single-cell imaging. Sci Rep 4:6522. doi: 10.1038/srep06522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tran TT, Panesso D, Mishra NN, Mileykovskaya E, Guan Z, Munita JM, Reyes J, Diaz L, Weinstock GM, Murray BE, Shamoo Y, Dowhan W, Bayer AS, Arias CA. 2013. Daptomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis diverts the antibiotic molecule from the division septum and remodels cell membrane phospholipids. mBio 4:e00281-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00281-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffiths JM, O'Neill AJ. 2012. Loss of function of the GdpP protein leads to joint β-lactam/glycopeptide tolerance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:579–581. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05148-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hallberg ZF, Wang XC, Wright TA, Nan B, Ad O, Yeo J, Hammond MC. 2016. Hybrid promiscuous (Hypr) GGDEF enzymes produce cyclic AMP-GMP (3′, 3′-cGAMP). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:1790–1795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515287113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. 2015. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc 10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reyes J, Panesso D, Tran TT, Mishra NN, Cruz MR, Munita JM, Singh KV, Yeaman MR, Murray BE, Shamoo Y, Garsin D, Bayer AS, Arias CA. 2015. A liaR deletion restores susceptibility to daptomycin and antimicrobial peptides in multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. J Infect Dis 211:1317–1325. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.