ABSTRACT

Ceftazidime-avibactam is a novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor with activity against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) that produce Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC). We report the first cases of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance to develop during treatment of CRE infections and identify resistance mechanisms. Ceftazidime-avibactam-resistant K. pneumoniae emerged in three patients after ceftazidime-avibactam treatment for 10 to 19 days. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of longitudinal ceftazidime-avibactam-susceptible and -resistant K. pneumoniae isolates was used to identify potential resistance mechanisms. WGS identified mutations in plasmid-borne blaKPC-3, which were not present in baseline isolates. blaKPC-3 mutations emerged independently in isolates of a novel sequence type 258 sublineage and resulted in variant KPC-3 enzymes. The mutations were validated as resistance determinants by measuring MICs of ceftazidime-avibactam and other agents following targeted gene disruption in K. pneumoniae, plasmid transfer, and blaKPC cloning into competent Escherichia coli. In rank order, the impact of KPC-3 variants on ceftazidime-avibactam MICs was as follows: D179Y/T243M double substitution > D179Y > V240G. Remarkably, mutations reduced meropenem MICs ≥4-fold from baseline, restoring susceptibility in K. pneumoniae from two patients. Cefepime and ceftriaxone MICs were also reduced ≥4-fold against D179Y/T243M and D179Y variant isolates, but susceptibility was not restored. Reverse transcription-PCR revealed that expression of blaKPC-3 encoding D179Y/T243M and D179Y variants was diminished compared to blaKPC-3 expression in baseline isolates. In conclusion, the development of resistance-conferring blaKPC-3 mutations in K. pneumoniae within 10 to 19 days of ceftazidime-avibactam exposure is troubling, but clinical impact may be ameliorated if carbapenem susceptibility is restored in certain isolates.

KEYWORDS: ceftazidime-avibactam, resistance, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase, sequence type 258

INTRODUCTION

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) have emerged worldwide as causes of infections that are resistant to front-line antibiotics (1). Mortality rates among patients with serious CRE infections are as high as 70% (2–4). The most common determinants of carbapenem resistance among Enterobacteriaceae in the United States are Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs), especially KPC-2 and KPC-3. Treatment of CRE infections has relied heavily upon salvage antibiotics like colistin, aminoglycosides, and tigecycline, which are limited by suboptimal pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and/or emergence of resistance (5, 6).

Avibactam is a novel β-lactamase inhibitor that inactivates KPCs, OXA-48 carbapenemases, AmpC, and extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), but not metallo-β-lactamases such as NDM, VIM, or IMP (7). The agent, by itself, is not active against KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae (KPC-Enterobacteriaceae). In combination, however, avibactam restores ceftazidime activity against KPC-Enterobacteriaceae in vitro (8). Ceftazidime-avibactam was approved in 2015 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections (in conjunction with metronidazole) and urinary tract infections (9–11). Data against KPC-Enterobacteriaceae infections are limited, but ceftazidime-avibactam is endorsed as front-line therapy due to its activity in vitro, its safety profile, and the lack of effective alternative regimens (7).

In a recent study, we described our experience at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) with ceftazidime-avibactam in treating 37 patients with CRE infections (12). Clinical success and survival at 30 days were 59% and 76%, respectively, rates that were comparable to those given in previous reports of CRE-infected patients treated with ≥2 in vitro-active agents (4). Ceftazidime-avibactam was well tolerated, with a 10% rate of acute kidney injury after ≥7 days of treatment, which was considerably lower than the ∼30% rate that we observed with colistin- or aminoglycoside-containing regimens (13, 14). As a counterpoint to these promising findings, ceftazidime-avibactam resistance emerged in three patients during treatment of KPC-producing K. pneumoniae infections. To our knowledge, these were the first descriptions of resistance developing during ceftazidime-avibactam treatment. To date, resistance mechanisms have not been described in KPC-producing clinical isolates.

Our objectives in this study were to provide detailed case reports of the emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance, identify and validate resistance mechanisms using genomic and molecular genetic approaches, and study the impact of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance mechanisms on susceptibility to meropenem and other β-lactam agents.

(These data were presented at ID Week 2016, October 2016, New Orleans, LA.)

RESULTS

Case reports.

Clinical and microbiologic details, timelines, and antimicrobial therapy are summarized in Fig. 1 and Table 1. Baseline isolates from each patient (isolates 1-A, 2-A, and 3-A) were meropenem resistant and ceftazidime-avibactam susceptible. Ceftazidime-avibactam was dosed at 2.5 g intravenously every 8 h (adjusted based on renal function) (9).

FIG 1.

Time courses of infection and treatment among patients in whom ceftazidime-avibactam-resistant K. pneumoniae emerged. Black and shaded bars represent duration of treatment with respective antibiotics. *, interpretation of K. pneumoniae phenotype, as reported by the clinical microbiology laboratory. Abbreviations: CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae; CTB, ceased to breathe; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; IAI, intra-abdominal infection; PNA, pneumonia; UTI, urinary tract infection.

TABLE 1.

K. pneumoniae isolates recovered from patients treated with ceftazidime-avibactama

| Patient-isolate ID | Days from admission to culture (source) | Ceftazidime-avibactam exposure at time of culture (days) | Ceftazidime-avibactam | MIC (μg/ml)b |

KPC-3 variantc | Relative fold change in blaKPC expression by qRT-PCRd | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftazidime | Meropenem | Ertapenem | Piperacillin-tazobactam | Cefepime | Ceftriaxone | Aztreonam | ||||||

| 1-A | 6 (sputum) | 0 | 2 (S) | 512 | 128 | 256 | >512 | >128 | >128 | >256 | Wild-type | Reference |

| 1-B | 20 (sputum) | 10 | 256 | >512 | 0.5 (S) | 1 | >512 | 16 | 32 | 8 | D179Y, T243 M | ↓ 2.64-fold |

| 1-C | 42 (sputum) | 24 | 256 | >512 | 0.25 (S) | 2 | >512 | 16 | 32 | 16 | D179Y, T243 M | NPe |

| 2-A | 7 (abscess) | 0 | 4 (S) | 256 | 32 | 8 | >512 | >128 | >128 | >256 | Wild-type | Reference |

| 2-B | 48 (urine) | 19 | 32 | >512 | 8 | 8 | >512 | >128 | >128 | >256 | V240G | <2-fold |

| 2-C | 48 (urine) | 19 | >256 | >512 | 4 | 16 | >512 | 16 | 4 | 8 | D179Y | ↓ 10.45-fold |

| 2-D | 78 (urine) | 19 | 4 (S) | 256 | 4 | 8 | >512 | >128 | >128 | >256 | T243A | <2-fold |

| 3-A | 6 (BALF) | 0 | 2 (S) | 256 | 32 | 8 | >512 | >128 | >128 | >256 | Wild-type | Reference |

| 3-B | 64 (BALF) | 15 | 128 | 512 | 0.25 (S) | 1 | 256 | 4 | 16 | 4 (S) | D179Y | ↓ 2.05-fold |

| 3-C | 82 (BALF) | 15 | 64 | 512 | 0.125 (S) | 0.5 | 256 | 8 | 16 | 4 (S) | D179Y | NP |

BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; S, susceptible, based on CLSI interpretive criteria (susceptibility breakpoints: ceftazidime-avibactam, ≤8 μg/ml; ceftazidime, ≤4 μg/ml; meropenem, ≤1 μg/ml; piperacillin-tazobactam, ≤16 μg/ml; cefepime, ≤2 μg/ml; ceftriaxone, ≤1 μg/ml; aztreonam, ≤4 μg/ml). Boldface rows represent baseline isolate from each patient.

MICs within the susceptible range are indicated by “(S)”; all other MICs indicated resistance.

When relevant, amino acid substitutions within KPC-3 are listed.

RT-PCR was performed for a representative isolate from each patient that expressed a given KPC-3 variant. Data show differences in gene expression relative to the corresponding baseline isolate (reference).

NP, RT-PCR not performed.

Patient 1, a double-lung transplant recipient in her 40s, was diagnosed with carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae pneumonia and urinary tract infection (isolate 1-A, recovered from sputum; ceftazidime-avibactam MIC, 2 μg/ml; meropenem MIC, 128 μg/ml) in November 2015. She was treated with 10 days of ceftazidime-avibactam. Four days after completing treatment, ceftazidime-avibactam and gentamicin were initiated for recurrent pneumonia. Sputum culture (isolate 1-B) grew meropenem-susceptible K. pneumoniae (MIC = 0.5 μg/ml), which was reported as ESBL producing. Ceftazidime-avibactam was discontinued after 14 days, and meropenem was administered because meropenem-susceptible (MIC = 0.25 μg/ml), ESBL K. pneumoniae was still identified in sputum culture (isolate 1-C). Both meropenem-susceptible isolates were ceftazidime-avibactam resistant (MICs = 256 μg/ml). Meropenem was given for 17 days (alone and then combined with gentamicin), but the patient died of respiratory failure. There were no epidemiological links between patient 1 and patient 2 or 3.

Patient 2, a woman in her 50s, was diagnosed with a subphrenic abscess due to carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (isolate 2-A; ceftazidime-avibactam MIC, 4 μg/ml; meropenem MIC, 32 μg/ml) in January 2016. She was successfully treated with abscess drainage and 19 days of ceftazidime-avibactam. Subsequent hospitalization was complicated by recurrent fevers and worsening of comorbid conditions. Work-up during these febrile episodes revealed urinary tract colonization with three different carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates, which was not treated (isolates 2-B, -C, and -D; meropenem MICs, 4 to 8 μg/ml). Two colonizing isolates (isolates 2-B and -C) were ceftazidime-avibactam resistant (MICs, 32 and >256 μg/ml). The patient was ultimately discharged.

Patient 3, a man in his 70s who had undergone esophagectomy for cancer, was diagnosed with pneumonia due to carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (isolate 3-A; ceftazidime-avibactam MIC, 2 μg/ml; meropenem MIC, 32 μg/ml) in January 2016. He was treated with ceftazidime-avibactam for 15 days. Thereafter, meropenem-susceptible, ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were identified as a respiratory tract colonizer or cause of recurrent pneumonia (isolates 3-B, 3-C; MICs, 0.25 and 0.125 μg/ml, respectively). Both isolates were ceftazidime-avibactam resistant (MICs, 64 and 128 μg/ml). Recurrent pneumonia was treated successfully with meropenem plus colistin for 14 days.

Characterization of K. pneumoniae isolates.

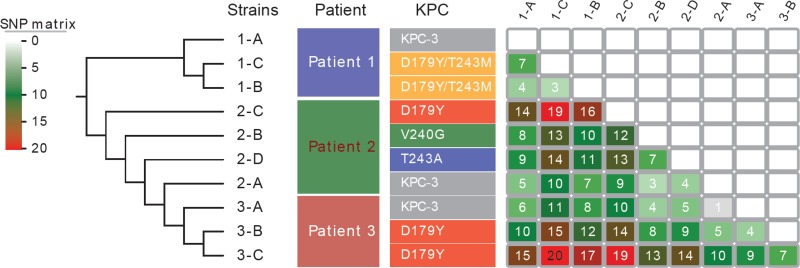

All 10 K. pneumoniae isolates were sequence type (ST) 258, clade II (cps-2, wzi allele 154) clones (Table 2) (15). Whole-genome sequences of these isolates were compared to those of 23 ST258, clade II isolates from our center (2010 to 2011) and others (Fig. 2). A total of 892 core single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified across the 33 isolates; 152 SNPs that were located at repetitive or prophage regions were excluded from phylogenetic analyses. An average of 91 SNPs (range, 1 to 214) were identified in pairwise comparisons of isolates, which is in agreement with our previous data that ST258, clade II isolates differed by ∼82 SNPs (range, 2 to 231) (15). The 10 isolates from this study clustered tightly with, but were divergent from, the other ST258, clade II K. pneumoniae isolates (Fig. 2 and 3; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 2.

Molecular characteristics of K. pneumoniae isolates from the present studya

| Patient no. | Strain ID | OmpK36 | KPC | blaKPC | Other resistance genes | Plasmid InC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-A | IS5 promoter ins | KPC-3 | blaKPC-3 | blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaOXA-9, aadA1, aac(6′)-Ib,strAB, sul2, dfrA14 | ColpVC,Col(MG828), pBK30683 repA, repB, pNJST258N3 |

| 1 | 1-B | WT | AA179D→Y, 243T→M | 532G→T, 725C→T | blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaOXA-9, aadA1, aac(6′)-Ib, strAB, sul2, dfrA14 | ColpVC,Col(MG828), pBK30683 repA, repB, pNJST258N3, L/M |

| 1 | 1-C | AA288stop | AA179D→Y, 243T→M | 532G→T, 725C→T | blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaOXA-9, aadA1, aac(6′)-Ib, strAB, sul2, dfrA14 | ColpVC,Col(MG828), pBK30683 repA, repB, pNJST258N3, L/M |

| 2 | 2-A | WT | KPC-3 | blaKPC-3 | blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaOXA-9, aadA1, aac(6′)-Ib, strAB, sul2, dfrA14 | pBK30683 repB, pNJST258N3 |

| 2 | 2-B | WT | AA240V→G (KPC-8) | 716T→G | blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaOXA-9, aadA1, aac(6′)-Ib, strAB, sul2, dfrA14 | pBK30683 repB, pNJST258N3 |

| 2 | 2-C | IS5 ins 827 bp | AA179D→Y | 532G→T | blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaOXA-9, aadA1, aac(6′)-Ib, strAB, sul2, dfrA14 | pBK30683 repB, pNJST258N3 |

| 2 | 2-D | WT | AA243T→A | 724G→A | blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaOXA-9, aadA1, aac(6′)-Ib, strAB, sul2, dfrA14 | pBK30683 repB, pNJST258N3 |

| 3 | 3-A | WT | KPC-3 | blaKPC-3 | blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaOXA-9, aadA1, aac(6′)-Ib, strAB, sul2, dfrA14 | pBK30683 repB, pNJST258N3 |

| 3 | 3-B | WT | AA179D→Y | 532G→T | blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaOXA-9, aadA1, aac(6′)-Ib, strAB, sul2, dfrA14 | pBK30683 repB, pNJST258N3 |

| 3 | 3-C | WT | AA179D→Y | 532G→T | blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaOXA-9, aadA1, aac(6′)-Ib, strAB, sul2, dfrA14 | pBK30683 repB, pNJST258N3 |

Abbreviations: InC, incompatibility group; KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase; WT, wild type. All isolates had the following features: sequence type (ST) 258; wzi allele 154; clade cps-2; OmpK35, AA89stop.

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic comparison of ST258, clade II K. pneumoniae isolates from our center and others in the United States. The phylogenetic tree, based on whole-genome SNP analysis, was generated with the use of the maximum-likelihood optimality criterion. Branch lengths are proportional to the number of evolutionary changes, and all nodes were supported by 100% bootstrap. Ten K. pneumoniae isolates from the present study and 22 isolates collected from hospitals in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Michigan in previous studies were included (15, 37, 39). Isolates from our medical center are presented in yellow ovals. Isolates in cluster a are from the present study, and isolates in cluster b were collected from our center in 2010 to 2011.

FIG 3.

SNP matrix of the 10 K. pneumoniae isolates from the present study. Numbers of SNPs for each pairwise comparison of isolates are shown.

All isolates had genes encoding TEM-1, SHV-11, and OXA-9 β-lactamases; none had genes encoding NDM, other metallo-β-lactamases, or OXA-48-like carbapenemases. Baseline isolates carried blaKPC-3. Subsequent isolates carried mutant blaKPC-3 encoding variant KPC-3 enzymes (Table 2). The most common KPC-3 variant featured a tyrosine for aspartic acid substitution at Ambler amino acid position 179 (D179Y), either alone (isolates 2-C, 3-B, and 3-C) or in combination with a methionine-for-threonine substitution at position 243 (D179Y/T243M; isolates 1-B and 1-C). Alanine-for-threonine and glycine-for-valine substitutions were observed at positions 243 (T243A) and 240 (V240G), respectively, in other isolates from patient 2; the V240G variant corresponds to KPC-8 (16). Each wild-type and mutant blaKPC-3 gene was in a ΔTn1331-Tn4401d nested transposon element, which was found within a common ∼40-kb contig. This contig is virtually identical to the corresponding region on IncFIA plasmid pBK30683, a predominant blaKPC-3-bearing plasmid in New York and New Jersey hospitals (17).

K. pneumoniae isolates with wild-type blaKPC-3 were ceftazidime-avibactam susceptible and meropenem resistant. Ceftazidime-avibactam MICs were increased ≥4-fold against isolates with mutant blaKPC-3 encoding D179Y/T243M, D179Y, and V240G variants compared to corresponding baseline isolates (Table 1); increased MICs conferred clinical drug resistance. Meropenem MICs against ceftazidime-avibactam-resistant isolates were reduced ≥4-fold, which restored meropenem susceptibility to isolates from patients 1 and 3. Cefepime, ceftriaxone, and aztreonam MICs were reduced ≥4-fold against D179Y/T243M and D179Y variant isolates. All isolates remained resistant to cefepime and ceftriaxone. The expression of blaKPC-3 encoding D179Y/T243M and D179Y variants was reduced compared to blaKPC-3 expression in corresponding baseline isolates. No mutations were evident within promoter sequences of mutant blaKPC-3 compared to wild-type blaKPC-3.

Validation of blaKPC-3 mutations.

Genes encoding D179Y/T243M, D179Y, and V240G KPC-3 variants were validated as causes of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance through three lines of evidence (Table 3). First, deletion of mutant blaKPC-3 in ceftazidime-avibactam-resistant K. pneumoniae restored drug susceptibility. Second, laboratory transfer of mutant blaKPC-3-containing plasmids from K. pneumoniae to Escherichia coli DH10B resulted in ≥4-fold increases in ceftazidime-avibactam MICs, compared to control, wild-type blaKPC-3 transformants. Third, ceftazidime-avibactam MICs also increased against E. coli DH5α harboring plasmid constructs with cloned mutant blaKPC-3, compared to E. coli DH5α with wild-type blaKPC-3 constructs. For mutant blaKPC-3 encoding D179/T243M, D179Y, and V240G variants, ceftazidime-avibactam MICs were increased ≥128-fold, ≥16-fold, and ≥4-fold, respectively. Mutant blaKPC-3 encoding D179/T243M and D179Y variants conferred ≥4-fold reductions in meropenem, cefepime, ceftriaxone, and aztreonam MICs against E. coli DH5α compared to wild-type blaKPC-3.

TABLE 3.

MICs against blaKPC-3 deletion mutants and E. coli transformantsa

| KPC-3 variant | Description | MIC range (μg/ml) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftazidime-avibactam | Ceftazidime | Meropenem | Piperacillin-tazobactam | Cefepime | Ceftriaxone | Aztreonam | ||

| Wild-type | Clinical isolates 1-A, 2-A, 3-A | 2–4 | 256–512 | 32–128 | >512 | >128 | >128 | >256 |

| Clinical isolate with blaKPC deletionb | 0.5 | 256 | ≤0.125 | 16–32 | 8 | 32 | >256 | |

| E. coli with blaKPC-containing plasmid from clinical isolatec | 1 | 128 | 2 | 256 | 32 | >128 | >256 | |

| E. coli with pET30a plasmid into which blaKPC was clonedd | ≤0.25–0.5 | 64–128 | 2–8 | >512 | >128 | >128 | >256 | |

| D179Y, T243 M | Clinical isolates 1-B, 1-C | 256 | >512 | 0.25–0.5 | >512 | 16 | 32 | 8 |

| Clinical isolate with blaKPC deletionb | ≤0.25 | 128 | ≤0.125 | 128 | 8 | 4 | 2 | |

| E. coli with blaKPC-containing plasmid from clinical isolatec | 64 | 256 | ≤0.125 | 64 | 8 | 32 | 64 | |

| E. coli with pET30a plasmid into which blaKPC was clonedd | 64 | ≥512 | ≤0.125 | 2–4 | 2–8 | 4–8 | 2–4 | |

| D179Y | Clinical isolates 2-C, 3-B, 3-C | 64 to >256 | ≥512 | 0.125–4 | 256 to >512 | 4–16 | 4–16 | 4–8 |

| Clinical isolate with blaKPC deletionb | ≤0.25 | 256 | ≤0.125 | 32–128 | 16 | 32 | >256 | |

| E. coli with blaKPC-containing plasmid from clinical isolatec | 16 | 128 | ≤0.125 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 2 | |

| E. coli with pET30a plasmid into which blaKPC was clonedd | 8 | 64 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | |

| V240G | Clinical isolate 2-B | 32 | >512 | 8 | >512 | >128 | >128 | >256 |

| Clinical isolate with blaKPC deletionb | 0.5 | 128 | ≤0.125 | 32 | 8 | 32 | >256 | |

| E. coli with blaKPC-containing plasmid from clinical isolatec | 4 | 512 | 1 | 256 | 32 | >128 | >256 | |

| E. coli with pET30a plasmid into which blaKPC was clonedd | 2 | 256 | 1 | 128 | 128 | >128 | >256 | |

Boldface rows represent baseline carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates.

blaKPC deletions were performed for a representative clinical isolate with each KPC-3 variant.

IncFIA pBK30683-like plasmids were extracted from representative clinical isolates and transferred into E. coli DH10B.

blaKPC genes from representative clinical isolates were cloned into a pET30a expression vector plasmid, which was transferred into E. coli DH5α. Ceftazidime-avibactam, ceftazidime, and meropenem MICs against E. coli DH5α carrying pET30a without blaKPC genes were ≤0.25, ≤0.5, and ≤0.125 μg/ml, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Ceftazidime-avibactam resistance due to plasmid-borne blaKPC-3 mutations appeared within 10 to 19 days of treatment in three patients with carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae infections. These findings are particularly concerning because K. pneumoniae isolates were all ST258, the most successful CRE worldwide (18), and ceftazidime-avibactam resistance arose through a variety of blaKPC-3 mutations. For some ceftazidime-avibactam-resistant isolates, blaKPC-3 mutations restored meropenem susceptibility, suggesting that their clinical impact may be ameliorated. However, carbapenem susceptibility was not restored against all ceftazidime-avibactam-resistant isolates, and the stability of the phenotype is unknown. MICs of other β-lactams were also reduced against blaKPC-3 mutant K. pneumoniae. Nevertheless, isolates generally remained resistant to these drugs, highlighting that other plasmid-mediated β-lactamases contribute to overall resistance phenotypes. Taken together, the data raise questions of whether blaKPC mutations that confer ceftazidime-avibactam resistance will emerge in CRE at other centers, mutant blaKPC will disseminate through horizontal gene transfer, and carbapenems will serve as effective salvage agents in treating at least some infections by such pathogens.

In rank order, the impact of KPC-3 variants on ceftazidime-avibactam MICs was as follows: D179Y/T243M > D179 > V240G. D179Y/T243M and D179Y variants caused comparable reductions in meropenem MICs, which were greater than with V240G. The results are in keeping with published laboratory data. Ceftazidime-avibactam resistance and KPC-3 amino acid substitutions arose at low frequency (∼10−9) in K. pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae during in vitro selection (19). D179Y emerged most frequently; a proline-for-threonine substitution at position 243 (T243P) was less common (19). D179Y and T243P mutants reverted to carbapenem susceptibility. In another study, introduction of substitutions at KPC-2 amino acid positions 179 and 243 by site-directed mutagenesis conferred ceftazidime-avibactam resistance in E. coli (20). E. coli recombinants carrying KPC-8 also exhibited significant increases in ceftazidime-avibactam MICs compared to control E. coli (16).

The mechanisms by which blaKPC-3 mutations mediate ceftazidime-avibactam resistance and reversion to carbapenem susceptibility are not defined. The KPC Ω-loop encompasses amino acid positions 165 through 179. KPC variants with Ω-loop substitutions demonstrate enhanced ceftazidime affinity, which is postulated to prevent binding of avibactam (20). Therefore, Ω-loop substitutions exert ceftazidime-related effects, but they are not thought to confer avibactam resistance per se (19, 20). KPC-3 has 9- to 30-fold-greater catalytic efficiency than KPC-2 against ceftazidime (21, 22), and we previously demonstrated that ceftazidime-avibactam MICs were significantly higher against blaKPC-3-producing than blaKPC-2-producing K. pneumoniae (8). These factors may predispose KPC-3-K. pneumoniae to ceftazidime-avibactam resistance (8). Stepwise mutations are well recognized to result in KPC variants with reduced hydrolytic activity against carbapenems (18). Kinetic studies are needed to determine if the KPC-3 substitutions described here attenuate carbapenemase activity. Finally, expression of mutant blaKPC-3 encoding D179Y/T243M or D179Y variants was significantly diminished; these preliminary data suggest that transcriptional regulation may modulate meropenem and ceftazidime-avibactam susceptibility patterns.

These are the first reports of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance emerging during treatment of CRE infections. Preexisting resistance is reported in up to 2 to 3% of Enterobacteriaceae in clinical trials and large biorepositories (8, 10, 11, 23, 24). In a recent report from a large U.S. cancer center, ceftazidime-avibactam resistance was detected in 6 CRE isolates that were shown subsequently to carry NDM-1 (25). Since NDM-1 is not inhibited by avibactam, the study described baseline ceftazidime-avibactam resistance rather than the emergence of resistance as documented in the present study. Two case reports, including one from the same cancer center, described ceftazidime-avibactam resistance in non-NDM-carrying K. pneumoniae isolates recovered from untreated patients (25, 26). One isolate harbored KPC-3, and the other did not carry a carbapenemase, but mechanisms of resistance were not identified. The three cases of drug resistance presented here accounted for 30% of microbiologic failures in our early experience with ceftazidime-avibactam against CRE infections (12).

Our WGS data indicate that ceftazidime-avibactam resistance arose within a novel K. pneumoniae ST258 sublineage. It is unclear at present if this sublineage is uniquely predisposed to the development of blaKPC-3 mutations or if mutations will be encountered at similar frequency in other ST258 populations, different STs, and diverse Enterobacteriaceae. Clearly, the 10 isolates here share a recent common ancestry. Nevertheless, resistance-conferring blaKPC-3 mutations were more likely to have evolved independently in different isolates (and in different patients) than to have emerged in a single parent isolate that subsequently disseminated. In support of this conclusion, patient 1 did not have any epidemiological links with patients 2 and 3. In addition, KPC variants had mutations at three distinct amino acid positions; even isolates from patients 2 and 3, who resided in the same unit, exhibited distinct amino acid substitutions. Longitudinal isolates from each of the patients were also heterogeneous in their core genomes, carrying noncumulative SNPs that varied from isolate to isolate; isolates from patients 1 and 2 demonstrated a variety of ompK36 porin genotypes. Therefore, patients appeared to harbor subpopulations of K. pneumoniae that evolved through different pathways from a common ancestor rather than in a direct lineage. Taken together, the findings highlight the well-recognized genetic plasticity and speed of evolutionary changes manifested by carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (27).

Due to the potential for rapid KPC spread and evolution, it is imperative that centers detect CRE isolates and infected patients in a timely fashion. Our cases illustrate the difficulties faced by clinical laboratories in this regard. Indeed, several ceftazidime-avibactam-resistant isolates were reported as meropenem-susceptible, ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae and were not identified as KPC producing. Such misidentification was inevitable since carbapenemase screening by our laboratory, as at many centers, is triggered by elevated carbapenem MICs. Routine molecular screening for blaKPC has been advocated for rapid detection of carbapenem resistance (28). However, such assays will need to detect specific genes, since KPC variants have different antibiotic affinities and hydrolytic properties. As shown here, sequencing the blaKPC gene directly or by next-generation genomics technologies may be necessary to identify and interpret the loss or gain of carbapenem and ceftazidime-avibactam susceptibility.

In conclusion, ceftazidime-avibactam is one of the few new antibiotics at an advanced stage of development that have anti-CRE activity. In order to preserve ceftazidime-avibactam, the medical community must define optimal dosing strategies (including the role of antibiotic combination regimens), adhere to rigorous stewardship and infection control practices, develop assays for detecting resistance and resistance determinants expeditiously, and understand resistance mechanisms. Together with reports of the recent emergence of MCR-1, the first plasmid-mediated colistin resistance determinant in Enterobacteriaceae (29), our findings attest to the urgent need for new drugs and treatment strategies against Gram-negative bacterial infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Susceptibility testing.

MICs were determined by broth microdilution according to Clinical Laboratory Standard Institutes (CLSI) guidelines (30). Antimicrobial agents were purchased from the UPMC pharmacy. Avibactam (kindly provided by AztraZeneca) was tested at a fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml in combination with ceftazidime (8). Susceptibility was defined according to CLSI interpretive criteria (31). Screening for ESBL production by the UPMC clinical microbiology laboratory used standard disc diffusion methods (31). In brief, isolates that were nonsusceptible to aztreonam and/or ceftriaxone were tested against ceftazidime and cefotaxime with and without clavulanic acid. Isolates demonstrating a ≥5-mm increase in zone diameter for either agent in combination with clavulanic acid were classified as ESBL.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and analysis.

Genomic DNA was prepared from overnight cultures using a Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Genome libraries were prepared using the Nextera DNA Library Preparation kit and sequenced using the Illumina NextSeq platform (paired end reads of 150 bp). Sequences were trimmed with sickle (GitHub), followed by de novo genome assembly using SPAdes 3.8 (32). In silico multilocus sequence typing and capsular wzi typing were performed using the BIGSdb online server (http://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/klebsiella.html). Antimicrobial resistance genes and plasmid replicons were identified using SRST2 (33). Novel plasmid replicons from our previous studies also were included in the analysis (15, 17).

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertion-deletions (indels) were called using BWA (34) and Samtools (35). SNP and indel annotation was conducted with SnpEff (36). K. pneumoniae isolate DMC1097 (37), an ST258 clade II (cps-2) strain from Detroit, MI, was used as reference. For core SNP analysis, SNPs located at repetitive (identified by nucmer from MUMmer) or prophage (identified by PHAST) regions of the genome were excluded. SNP phylogenetic analysis was performed using RAxML 8.0.0 (38). In addition, 22 ST258 clade II isolates from New Jersey (NJST258_1, NJST258_2, 1748, 1750, 1756, 1757) (15), New York (1765, 1790, 1789, 1814, 1801, 1780, 1764, 1824) (15), Maryland (KPNIH1, accession number CP008827) (39), Michigan (DMC1097, CP011976) (37), and UPMC (1818, 1808, 1809, 1816, 1811, 1817) (15) were included in the core SNPs analysis.

qRT-PCR.

DNase-treated RNA was obtained from late-exponential-phase cultures (Mueller-Hinton broth, 37°C; RiboPure-Bacteria kit, ThermoFisher Scientific, MA). cDNA was made using qScript cDNAMix (Quanta Biosciences, MD). Quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR was performed using the Applied Biosystems 7900 system, with established blaKPC primers and the SYBR green kit (Quanta Biosciences, MD) (40). blaKPC expression was normalized to housekeeping gene rpoB. In each case, relative expression was calibrated against corresponding baseline isolates that were susceptible to ceftazidime-avibactam.

blaKPC gene deletion.

blaKPC genes in K. pneumoniae isolates were deleted using the Red/ET system (Gene Bridges, Heidelberg, Germany), according to the manufacturer's protocol with slight modifications. In brief, K. pneumoniae isolates were transformed with the pRED/ET plasmid, which contains all genes necessary for homologous recombination. A linear DNA fragment, comprising the FRT-PGK-gb2-arr3-FRT cassette (in which a kanamycin resistance gene was replaced by an arr3 rifampin resistance gene) with 50-bp homology arms targeting the upstream and downstream sequence of blaKPC, was PCR amplified. The amplicon was electroporated into K. pneumoniae cells, resulting in replacement of blaKPC through recombination. Transformants, selected on lysogeny broth (LB) agar containing 100 μg/ml of rifampin, were confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

Plasmid transfer.

Plasmid DNA from K. pneumoniae isolates, extracted using a Qiagen Plasmid Midi kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), was electroporated into Escherichia coli DH10B (Invitrogen) using a Gene Pulser II instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories). E. coli DH10B transformants were selected on LB agar plates with 20 μg/ml ceftazidime. Transformants were screened by multiplex real-time PCR for the presence of blaKPC genes (41) and checked by S1-PFGE (S1 nuclease digestion of plasmid DNA followed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis) for the presence of a single blaKPC-harboring plasmid. Mutations within blaKPC genes were confirmed using standard PCR and sequencing.

blaKPC-3 cloning.

blaKPC and flanking regions (600 bp upstream, 240 bp downstream) were amplified from plasmid DNA by PCR using primers KPC3_For_KpnI (CGGGGTACCCTGCTGGTGATCGATGAGAT) and KPC3_Rev_EcoRI (CCGGAATTCTTAAATGGGGCGGCTCAAAT), which contained introduced KpnI and EcoRI restriction sites, respectively (underlined). Amplicons were digested and ligated in the antisense direction into pET30a (Novagen, Madison, WI); inserts were sequenced on both strands. Plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α by electroporation. Successful transfer of blaKPC genes was confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

Accession number(s).

Sequence data have been deposited in NCBI under BioProject number PRJNA326665.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K08AI114883 to R.K.S., R21AI117338 to L.C., R01AI090155 to B.N.K., UM1AI104681 to M.H.N., and R21AI111037 to C.J.C.).

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02097-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. 2013. Vital signs: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 62:165–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tumbarello M, Trecarichi EM, De Rosa FG, Giannella M, Giacobbe DR, Bassetti M, Losito AR, Bartoletti M, Del Bono V, Corcione S, Maiuro G, Tedeschi S, Celani L, Cardellino CS, Spanu T, Marchese A, Ambretti S, Cauda R, Viscoli C, Viale P, Isgri S. 2015. Infections caused by KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: differences in therapy and mortality in a multicentre study. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2133–2143. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daikos GL, Tsaousi S, Tzouvelekis LS, Anyfantis I, Psichogiou M, Argyropoulou A, Stefanou I, Sypsa V, Miriagou V, Nepka M, Georgiadou S, Markogiannakis A, Goukos D, Skoutelis A. 2014. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections: lowering mortality by antibiotic combination schemes and the role of carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2322–2328. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02166-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tzouvelekis LS, Markogiannakis A, Piperaki E, Souli M, Daikos GL. 2014. Treating infections caused by carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Infect 20:862–872. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrill HJ, Pogue JM, Kaye KS, LaPlante KL. 2015. Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 2:ofv050. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monaco M, Giani T, Raffone M, Arena F, Garcia-Fernandez A, Pollini S, Network EuSCAPE-Italy, Grundmann H, Pantosti A, Rossolini GM. 2014. Colistin resistance superimposed to endemic carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: a rapidly evolving problem in Italy, November 2013 to April 2014. Euro Surveill 19(42):pii=20939 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/images/dynamic/EE/V19N42/art20939.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Duin D, Bonomo RA. 2016. Ceftazidime/avibactam and ceftolozane/tazobactam: second-generation beta-lactam/beta-lactamase combinations. Clin Infect Dis 63:234–241. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shields RK, Clancy CJ, Hao B, Chen L, Press EG, Iovine NM, Kreiswirth BN, Nguyen MH. 2015. Effects of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase subtypes, extended-spectrum beta-lactamases and porin mutations on the in vitro activity of ceftazidime-avibactam against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:5793–5797. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00548-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2016. Acycaz (ceftazidime-avibactam). Prescribing information. Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Cincinnati, OH. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmeli Y, Armstrong J, Laud PJ, Newell P, Stone G, Wardman A, Gasink LB. 2016. Ceftazidime-avibactam or best available therapy in patients with ceftazidime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa complicated urinary tract infections or complicated intra-abdominal infections (REPRISE): a randomised, pathogen-directed, phase 3 study. Lancet Infect Dis 16:661–673. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazuski JE, Gasink LB, Armstrong J, Broadhurst H, Stone GG, Rank D, Llorens L, Newell P, Pachl J. 2016. Efficacy and safety of ceftazidime-avibactam plus metronidazole versus meropenem in the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infection—results from a randomized, controlled, double-blind, phase 3 program. Clin Infect Dis 62:1380–1389. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shields RK, Potoski BA, Haidar G, Hao B, Doi Y, Chen L, Press EG, Kreiswirth BN, Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. 2016. Clinical outcomes, drug toxicity and emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance among patients treated for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Clin Infect Dis 63:1615–1618. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Potoski BA, Press EG, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Clarke LG, Eschenauer GA, Clancy CJ. 2015. Doripenem MICs and ompK36 porin genotypes of sequence type 258, KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae may predict responses to carbapenem-colistin combination therapy among patients with bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1797–1801. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03894-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shields RK, Clancy CJ, Press EG, Nguyen MH. 2016. Aminoglycosides for treatment of bacteremia due to carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:3187–3192. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02638-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deleo FR, Chen L, Porcella SF, Martens CA, Kobayashi SD, Porter AR, Chavda KD, Jacobs MR, Mathema B, Olsen RJ, Bonomo RA, Musser JM, Kreiswirth BN. 2014. Molecular dissection of the evolution of carbapenem-resistant multilocus sequence type 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:4988–4993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321364111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papp-Wallace KM, Winkler ML, Taracila MA, Bonomo RA. 2015. Variants of beta-lactamase KPC-2 that are resistant to inhibition by avibactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3710–3717. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04406-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L, Chavda KD, Melano RG, Hong T, Rojtman AD, Jacobs MR, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2014. Molecular survey of the dissemination of two blaKPC-harboring IncFIA plasmids in New Jersey and New York hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2289–2294. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02749-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolter DJ, Kurpiel PM, Woodford N, Palepou MF, Goering RV, Hanson ND. 2009. Phenotypic and enzymatic comparative analysis of the novel KPC variant KPC-5 and its evolutionary variants, KPC-2 and KPC-4. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:557–562. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00734-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livermore DM, Warner M, Jamrozy D, Mushtaq S, Nichols WW, Mustafa N, Woodford N. 2015. In vitro selection of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance in Enterobacteriaceae with KPC-3 carbapenemase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:5324–5330. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00678-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winkler ML, Papp-Wallace KM, Bonomo RA. 2015. Activity of ceftazidime/avibactam against isogenic strains of Escherichia coli containing KPC and SHV beta-lactamases with single amino acid substitutions in the Omega-loop. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2279–2286. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alba J, Ishii Y, Thomson K, Moland ES, Yamaguchi K. 2005. Kinetics study of KPC-3, a plasmid-encoded class A carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:4760–4762. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4760-4762.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta SC, Rice K, Palzkill T. 2015. Natural variants of the KPC-2 carbapenemase have evolved increased catalytic efficiency for ceftazidime hydrolysis at the cost of enzyme stability. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004949. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castanheira M, Mills JC, Costello SE, Jones RN, Sader HS. 2015. Ceftazidime-avibactam activity tested against Enterobacteriaceae isolates from U.S. hospitals (2011 to 2013) and characterization of beta-lactamase-producing strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3509–3517. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00163-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castanheira M, Mendes RE, Jones RN, Sader HS. 2016. Changing of the frequencies of beta-lactamase genes among Enterobacteriaceae in U.S. hospitals (2012 to 2014): activity of ceftazidime-avibactam tested against beta-lactamase-producing isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:4770–4777. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00540-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aitken SL, Tarrand JJ, Deshpande LM, Tverdek FP, Jones AL, Shelburne SA, Prince RA, Bhatti MM, Rolston KV, Jones RN, Castanheira M, Chemaly RF. 2016. High rates of non-susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam and identification of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase production in Enterobacteriaceae bloodstream infections at a major cancer center. Clin Infect Dis 63:954–958. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphries RM, Yang S, Hemarajata P, Ward KW, Hindler JA, Miller SA, Gregson A. 2015. First report of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance in a KPC-3 expressing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6605–6607. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01165-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynch T, Chen L, Peirano G, Gregson DB, Church DL, Conly J, Kreiswirth BN, Pitout JD. 2016. Molecular evolution of a Klebsiella pneumoniae ST278 isolate harboring blaNDM-7 and involved in nosocomial transmission. J Infect Dis 214:798–806. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humphries RM, McKinnell JA. 2015. Continuing challenges for the clinical laboratory for detection of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol 53:3712–3714. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02668-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, Doi Y, Tian G, Dong B, Huang X, Yu LF, Gu D, Ren H, Chen X, Lv L, He D, Zhou H, Liang Z, Liu JH, Shen J. 2016. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard—10th edition: approved standard M07-A10. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2016. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 26th ed (M100S). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inouye M, Dashnow H, Raven LA, Schultz MB, Pope BJ, Tomita T, Zobel J, Holt KE. 2014. SRST2: rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Med 6:90. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, Land SJ, Lu X, Ruden DM. 2012. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright MS, Perez F, Brinkac L, Jacobs MR, Kaye K, Cober E, van Duin D, Marshall SH, Hujer AM, Rudin SD, Hujer KM, Bonomo RA, Adams MD. 2014. Population structure of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Midwestern U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4961–4965. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00125-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Thomas PJ, Stock F, Henderson DK, Palmore TN, Segre JA. 2012. Tracking a hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with whole-genome sequencing. Sci Transl Med 4:148ra116. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Landman D, Bratu S, Quale J. 2009. Contribution of OmpK36 to carbapenem susceptibility in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Med Microbiol 58:1303–1308. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.012575-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L, Mediavilla JR, Endimiani A, Rosenthal ME, Zhao Y, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2011. Multiplex real-time PCR assay for detection and classification of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase gene (blaKPC) variants. J Clin Microbiol 49:579–585. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01588-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.