ABSTRACT

Neuronal migration is an essential step in the formation of laminated brain structures. In the developing cerebral cortex, pyramidal neurons migrate toward the Reelin-containing marginal zone. Reelin is an extracellular matrix protein synthesized by Cajal-Retzius cells. In this review, we summarize our recent results and hypotheses on how Reelin might regulate neuronal migration by acting on the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton. By binding to ApoER2 receptors on the migrating neurons, Reelin induces stabilization of the leading processes extending toward the marginal zone, which involves Dab1 phosphorylation, adhesion molecule expression, cofilin phosphorylation and inhibition of tau phosphorylation. By binding to VLDLR and integrin receptors, Reelin interacts with Lis1 and induces nuclear translocation, accompanied by the ubiquitination of phosphorylated Dab1. Eventually Reelin induces clustering of its receptors resulting in the endocytosis of a Reelin/receptor complex (particularly VLDLR). The resulting decrease in Reelin contributes to neuronal arrest at the marginal zone.

KEYWORDS: cofilin phosphorylation, Dab1 phosphorylation, endocytosis, nuclear translocation, radial neuronal migration, receptor clustering, reelin receptors, stabilization of cytoskeleton

Radial migration of pyramidal neurons along a radial glial scaffold

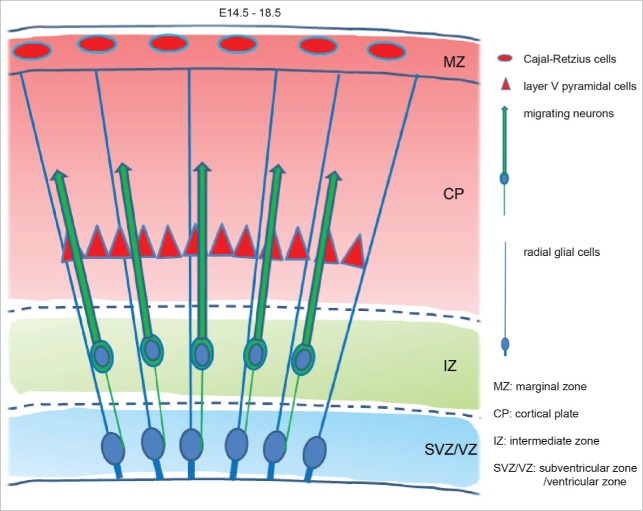

During brain development newborn pyramidal neurons of the cerebral cortex migrate from their place of origin, the ventricular zone, toward the pial surface of the cerebral cortex along radial glial processes.1-3 In an inside-out patterning, they form the 6-layered cortical plate with early-generated neurons accumulating in the deep layers and newly arriving cells occupying the superficial layers where migration is stopped.1,3,4 Pyramidal neurons are generated by radial glial cells which are located in the ventricular zone and asymmetrically give rise to a new radial glial cell and a postmitotic pyramidal neuron or an intermediate progenitor daughter cell.5-10 Radial glial cells extend a thick apical process attaching to the ventricle and a thin, long radial glial fiber connecting to the pial surface. This fiber is not resorbed during division.11 The newborn pyramidal neuron inherits the pial fiber and also grows a thick ventricular process for several hours when the cerebral wall is very thin and pyramidal neurons can reach their proper positions in the cortex by using somal translocation without glial guidance.11 This process involves progressive shortening and thickening of the process attached to the pia, advancement of the soma toward the pial surface, and arrest of migration beneath the marginal zone.3 At a later stage, the cerebral wall becomes increasingly thicker and the ventricular process of migrating neurons collapses, contributing to the ascent of neurons toward the pial surface.3 The pia-directed process (known as leading process) also detaches from the pia and the neuron migrates along a radial glial fiber in a saltatory manner (locomotion).3 As soon as the leading processes reach the marginal zone, locomotion is switched to somal translocation without glial guidance (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic view of neurons at E14.5–18.5 migrating radially along radial fibers toward the marginal zone.

Reelin protein and its receptors

Why do neurons always migrate toward the pial surface but never enter the marginal zone? Previous studies have shown that Reelin, an extracellular matrix protein synthesized and secreted by Cajal-Retzius cells located in the marginal zone, plays an important role in controlling neuronal migration.12,13 The marginal zone (future layer I) and the subplate are the first layers to form from a primordial plexiform neuropil at embryonic days (E) 10–11.14,15,16 Cajal-Retzius cells represent the main cell population of the marginal zone at this stage. At E13.5 neurons generated from the ventricular zone of the cortex invade the preplate by separating marginal zone and subplate, thus forming the cortical plate.17 A substantial proportion of neurons in the marginal zone, in the subplate and in the lower intermediate zone are generated in the medial ganglionic eminence, the pallidal primordium. These neurons follow a tangential migratory route to their positions in the developing cortex.16 Approximately 75% of Cajal-Retzius cells disappear by apoptosis after postnatal day 8 (P8) when the whole migratory process has come to an end.18

By guiding radially migrating neurons towards the marginal zone, Reelin has been proposed to act as a chemoattractant19 or a positional signal.20 Reelin is a glycoprotein with a molecular weight of about 400 KDa; it is subject to proteolytic cleavage at two sites after secretion, which produces five different fragments, 320 kDa, 240 kDa, 180kDa, 120 kDa and 100 kDa, respectively.21,22 Inhibition of Reelin processing prevents cortical development.23 Full-length Reelin and the larger fragments might not diffuse over long distances and remain in the marginal zone. Only N-terminal and central fragments are able to diffuse within the cortical plate after cleavage.23 Furthermore, the central fragment of Reelin has been shown in vivo to be critical for Reelin's function during cortical development.24 Whether or not different fragments of Reelin in different locations of the cortex exert different functions has remained obscure. In reeler mutant mice, which lack Reelin and its fragments, layer formation is inverted and late-generated neurons cannot bypass their predecessors. They pile up in deep layers of the cerebral cortex.25-30

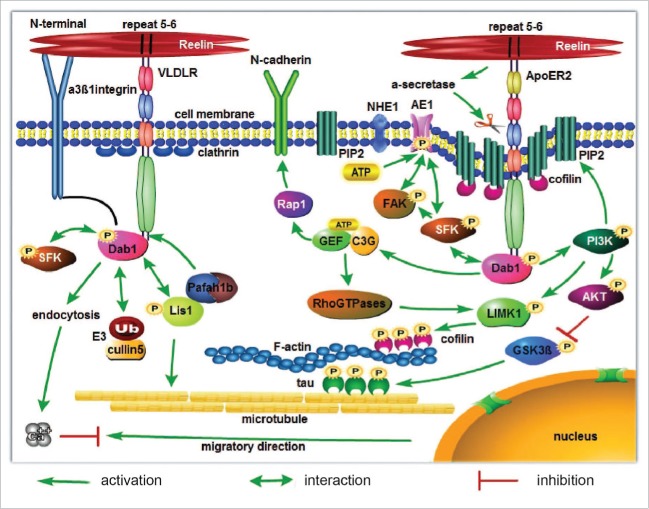

Many studies have shown that Reelin binds to 2 lipoprotein receptors on the migrating neurons, apolipoprotein-E receptor 2 (ApoER2 also known as Lrp8) and very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR).31-33 The consecutive presence of the fifth and sixth Reelin repeat is required for both ApoEr2 and VLDLR receptor-binding.34 The binding of Reelin to these 2 receptors induces phosphorylation of the adaptor protein disabled 1 (Dab1).35,36 ApoER2 and VLDLR double-knockout mice and Dab1 knockout mice show similar neuronal migration defects as seen in reeler mutants. Single receptor knockout mice display milder migration defects.29,31,37-40 It has also been shown that alpha3beta1 integrin receptors bind to the N-terminal region of Reelin, a site distinct from the region known to associate with the Reelin receptors ApoER2/VLDLR (Fig. 2). Alpha3 integrin is expressed in layers II–V in the developing cerebral cortex and β 1integrin in layers I-V. Alpha3 integrin maintains neurons in a glial state until glia-guided neuronal migration is terminated by the binding of Reelin to the alpha3 beta1 integrin dimer, which triggers the interaction of Dab1 with the cytoplasmic region of beta1 integrin (Fig. 2).41,43,44 Beta1 integrin is expressed in cortical neurons and glial cells starting at about E10.5. It regulates glial endfeet anchorage, meningeal basement membrane remodeling, and the formation of the layer of Cajal-Retzius cells.44 Beta1 integrin-deficient neurons invade the marginal zone similar to the invasion of the marginal zone in reeler mice.44 Further studies have shown that alpha3beta1 integrins are co-expressed with Dab1 in embryonic cortical neurons and that absence of these integrins leads to reduced Dab1 expression, indicating that deficiency of functional alpha3beta1 integrins results in impaired Reelin function in vitro and in vivo.43

Figure 2.

A summary diagram of Reelin signaling pathways involving cell membrane receptors, the major lipid products of PI3K: PIs and intracellular downstream molecules.

Since the Reelin-containing marginal zone in wildtype mice is almost cell-free but is invaded by numerous neurons in the reeler mutant, Reelin has been suggested to act as a stop or detachment signal for the migrating neurons.29,43-48 By binding to VLDLR or integrin receptors on the leading processes, Reelin in the marginal zone seems to arrest migrating neurons.29,41-44,48-51

Reelin signaling regulates the expression of adhesion molecules on migrating neurons

Reelin is not only expressed in the marginal zone of the cerebral cortex but is also detectable in the germinal zone and in layer V neurons of the cortical plate (Fig. 1).23,46,52,53

During radial migration, Reelin activates Rap1, which, in turn, upregulates N-cadherin (Fig. 2).54-56 Neurons in the intermediate zone of the cortex polarize and concentrate N-cadherin in their plasma membrane where the first process will form. Downregulation of N-cadherin results in a delay of polarization and migration.57 Similarly, without Rap1 cortical pyramidal neurons still polarize, but leading process stabilization and nuclear translocation are affected.56 N-cadherin simultaneously engages in homophilic interactions resulting in the consolidation of the adhesion point, which is crucial for nuclear translocation.58 This indicates that Reelin-signaling induces polarization of neurons in the intermediate zone from a multipolar to a bipolar shape and stabilizes the leading processes by regulating expression of focal adhesion molecules, which is critical for nuclear translocation near the marginal zone.

Distinct distribution of ApoER2/VLDLR determines Reelin's function

Our previous study has shown that Reelin signaling induces phosphorylation of cofilin in the leading processes of migrating neurons. In reeler mutant mice, ApoER2/VLDLR double knockout mice and Dab1 mutants cofilin phosphorylation is strongly reduced.46 We found that Reelin–induced phosphorylation of cofilin is more dependent on ApoER2 than VLDLR.46 Are there any functional differences between these 2 receptors and are they differentially distributed? Indeed, a recent study has revealed that ApoER2 is mainly localized to neuronal processes and cell membranes of multipolar cells in the intermediate zone, whereas VLDLR is primarily expressed in the cortical plate adjacent to Reelin-expressing cells in the marginal zone.48 Detailed analysis showed that VLDLR is localized to the distal portions of leading processes in the marginal zone.48 These different expression patterns may contribute to the distinct actions of Reelin on migrating neurons during radial migration in the developing cerebral cortex.48 We speculate that by binding to ApoER2 on the somal membrane, Reelin signaling contributes to the formation of a bipolar shape and the determination of the future leading process, stimulates the activity of LIMK1 that phosphorylates cofilin, and stabilizes the leading process along the radial glial fiber. In reeler mutant mice, late generated neurons fail to migrate to their final positions in the upper layers of the cortical plate and even migrate backward to the ventricular zone, likely because their leading processes are not stabilized and anchored to the marginal zone.30

As soon as the leading processes attach to the Reelin-containing marginal zone, neurons detach from the radial glial fiber and switch from locomotion to nuclear translocation.3,29,30,42,43,46,48,50,51 What is the role of Reelin in this process? We have mentioned before that Reelin binds to alpha3beta1 intergrin receptors and interacts with Dab1 via their intracellular domains and induces detachment of migrating neurons from the radial glia.42,43

It has been suggested that Reelin by binding to lipoprotein receptors simultaneously induces homodimerization and clustering of receptors.59,60 Clustering of receptors triggers the downstream signaling including phosphorylation of Dab1 and its interaction with Src family kinases (SFKs).60 Phosphorylation of Dab1 leads to its degradation by ubiquitination.61 Clustering of receptors also initiates clathrin-dependent receptor endocytosis.62 However, ApoER2 is only found in caveolae-rich membrane fractions,63,64 distinguishing it from the non-lipid-raft VLDLR.62 Upon receptor clustering, ApoER2 translocates from rafts to non-raft domains of the membrane in order to join clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Reelin and ApoER2 are both endocytosed and end up in the lysosome. The endocytosis rate of Reelin with ApoER2 is much slower than Reelin with VLDLR and is slower in regions of the brain where mostly ApoER2 is expressed. The Reelin-ApoER2-induced activation of target cells is not accompanied by a reduction of Reelin.62 Binding of Reelin to VLDLR induces direct internalization of a Reelin/VLDLR complex. VLDLR then dissociates from Reelin and can be recycled back to the cell membrane.62 Reelin is rapidly degraded in the lysosome compartment.62 It has been noticed that ApoER2 has a furin cleavage site in the intracellular domain, and after cleavage the resulting receptor fragment consisting of the entire ligand-binding domain is secreted.65 Another observation was that binding of Reelin to ApoER2 stimulates the α-secretase-mediated ApoER2 cleavage, producing extracellular soluble fragments of ApoER2 containing the ligand binding domain.62 These fragments of ApoER2 could act as dominant-negative receptors and inhibit Reelin signaling (Fig. 2).62,65 Therefore, it is possible that Reelin by inducing cleavage of ApoER2 inhibits further Reelin signaling as the leading process enters the marginal zone. Endocytosis of the Reelin/VLDLR complex does take place very quickly resulting in a rapid local decrease of extracellular Reelin and eventually loss of Reelin function62 neuronal migration is stopped.

We may speculate that during migration Reelin binds to ApoER2 on the leading process and triggers downstream signaling of Reelin intracellularly to stabilize the cytoskeleton. As soon as the leading process of a migrating neuron reaches the marginal zone, Reelin clusters its receptors on the leading process, Dab1 is phosphorylated and eventually ubiquinated (see below). Clustering of Reelin receptors will induce endocytosis of the Reelin/VLDLR complex and probably also of ApoER2. In VLDLR knockout mice, but not in ApoER2 mutants, many neurons invade the marginal zone. In contrast, ApoER2 knockout mice show a similar migration defect as reeler mutants with late-born neurons accumulating in deep cortical layers.29 The findings imply that ApoER2 is more important for Reelin's function in the migratory process, whereas VLDLR is likely to contribute to migration arrest.

Dab1 – key adaptor protein for Reelin function

In the developing embryonic cortex, Dab1 is present in neurons of the cortical plate, intermediate zone, and ventricular zone.66 It may function as a docking protein to link proteins together through its amino-terminal PI/PTB domain and tyrosine-phosphorylated motifs within the cell.67 Previous work has suggested that Reelin both activates and down-regulates its effector Dab1, first by inducing its phosphorylation and then by being a target of the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex containing SOCS family proteins and cullin5 (Fig. 2). The down-regulation of Dab1 in vivo leads to a unique phenotype in the cortex where neurons migrate past their target layer by Dab1-dependent terminal translocation resulting in an inside-out alignment within the cortical plate.68,69 Blockade of VLDLR and ApoER2 correlates with the loss of Reelin-induced Dab1 phosphorylation in cultured primary embryonic neurons.33 Dab1 knockout mice display a reeler-like phenotype, and in the reeler mutant and in ApoER2/VLDLR double knockout mice Dab1 is upregulated, indicating that these receptors are indispensable for Dab1 phosphorylation.31 It has been also noticed that Dab1 phosphorylation is independent of receptor localization in lipid rafts.64 However, In vivo studies have shown that Dab1 phosphorylation alone does not rescue the reeler phenotype if Reelin endocytosis is not stimulated.62 Therefore, VLDLR-mediated Reelin endocytosis is critical for terminal nuclear translocation, which is accompanied by the ubiquitination of phosphorylated Dab1.70 Overexpression of Dab1 prevents endocytosis of Reelin receptors suggesting that endocytosis of Reelin receptors is mediated by Dab1 phosphorylation.71,72

In our previous paper we have shown that Reelin-induced phosphorylation of cofilin is reduced if neurons were treated with Dab1 inhibitor. Moreover, in Dab1 knockout mice cofilin phosphorylation is strongly decreased, suggesting that phosphorylation of Dab1 is important for cofilin phosphorylation induced by Reelin binding to ApoER2.46

Reelin stabilizes the microtubule cytoskeleton of migrating neurons

Reelin signaling also regulates microtubule dynamics during neuronal migration. By binding to ApoER2 receptors, the Reelin signal inhibits GSK-3beta activity. GSK-3 β is known to phosphorylate the microtubule-stabilizing protein tau (Fig. 2).33,73 In reeler mutant mice, GSK-3 β activity is increased leading to hyperphosphorylation of tau, which results in destabilization of the tubulin cytoskeleton.33,74 Lis1, a subunit of the platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase (Pafah) and encoded by the Pafah1b1 gene, has been shown to cross-talk with Reelin signaling and is equally important for neuronal migration. Loss of the Reelin or Lis1 gene causes lissencephaly, a human neuronal migration disorder. Lis1+/− mice show migration defects of neurons, whereas homozygous mutants are embryonic lethal.75 By interacting with tubulin, Lis1 suppresses microtubule dynamics and reduces microtubule catastrophe events, thereby stabilizing the microtubules.77 Lis1 binds the catalytic subunits of the Pafah1b complex (α1 and α2), which specifically bind to the NPxY sequence of VLDLR, but not to ApoER2. The binding of Pafah1b complex (α1 and α2) to VLDLR may displace phosphorylated Dab1 and promote its interaction with Lis1 (Fig. 2).75-78 Therefore, Dab1 phosphorylation induced by binding of Reelin to VLDLR promotes endocytosis of the Reelin-receptor complex and then Dab1 is displaced from the NPxY motif of VLDLR by the Pafah1b complex. Released phosphorylated Dab1 binds to Lis1 to stabilize the microtubule cytoskeleton for nuclear translocation. Regarding Reelin's role in nuclear translocation it was also found that Reelin promotes formation of the microtubule plus end binding protein 3 (EB3) in the marginal zone.78 It should be noticed that inhibition of LIS1 function only blocks nuclear translocation without affecting the centrosome in the leading process, suggesting that movement of the nucleus and centrosome are differentially regulated.79 Therefore, Reelin stabilizes the actin cytoskeleton by binding to ApoER2 receptors and stabilizes the microtubule cytoskeleton by binding to VLDLR to promote nuclear translocation.

PIs are involved in Reelin's effects on the actin cytoskeleton

Upon binding of Reelin to ApoER2, Dab1 is tyrosine-phosphorylated by SFKs and is targeted to the caveolae-rich membrane by its PTB domain, binding to NPXY motifs of ApoER2.73 This reaction triggers phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) activity which catalyzes the formation of phosphoinosides (PIs). PI3K phosphorylates inositol phospholipids, producing 3 lipid products: PtdIns(3)P, PtdIns(3,4)P2 and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (Fig. 2). These lipids bind to the pleckstrin homology (PH) domains of proteins and control the activity of subcellular signal transduction and anchor numerous signaling molecules to the cell membrane for cytoskeleton regulation.80,82 Guanine-nucleotide-exchange proteins for Rho family GTPases are regulated this way (Fig. 2).80 We know that Rho family GTPases are regulators of LIMK1 which phosphorylates cofilin (Fig. 2).81 It has been shown that absence of the Ras family guanine nucleotide exchange factor C3G (Cyanidin-3-Glucoside, a Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor) results in a strong migration defect similar to that in reeler: C3G-deficient cortical neurons fail to migrate, fail to split the preplate and subplate, and fail to form a cortical plate. Instead, they arrest in a multipolar state and accumulate below the preplate. C3G is activated in response to Reelin signaling in cortical neurons, which, in turn, leads to activation of the small GTPase Rap1. Rap1 is known to upregulate N-cadherin (Fig. 2).54-56,83 These observations strongly suggest that intracellular transduction of Reelin signaling is PI-dependent. Methyl-ß-cyclodextrin (MßCD) treatment, which depletes cellular membranes of cholesterol, greatly reduced Dab1 phosphorylation, SFKs, and protein kinase B (also known as Akt) activation which are induced by Reelin signaling.73

Reelin signaling, interaction of PIs with cofilin at the cell membrane, and regulation of intracellular pH and Ca2+ in the leading process

It is intriguing that cofilin is co-localized with PIP2 in lipid rafts.84 Three compartments of cofilin in the cell have been identified: the cytosolic, plasma membrane and F-actin-bound compartments.84 The activity of cofilin is inhibited by several mechanisms, such as phosphorylation at Ser-3 residue near the N-terminus,46,85 by the binding of PIP2 (Fig. 2),86 and by an increase in intracellular pH.87 It has been shown that PIP2 activates protein kinase C (PKC).88,89 Inhibition of PKC induces a reeler-like malformation of cortical plate development,90 indicating that activation of PKC is necessary for Reelin signaling.

Binding of cofilin to PIP2 is pH-dependent, with decreased binding at a higher pH.86 Cofilin in the actin-rich leading edge of lamellipodia is not bound to membrane PIP2 and therefore active.84 Active cofilin binds to and severs F-actin, increases the number of free barbed ends91 and promotes actin polymerization and lamellipod formation.84 Rapid biphasic increase in actin free barbed ends is absent in fibroblasts lacking H+ efflux by the Na-H exchanger NHE1.86

The anion exchangers (AEs) are membrane Cl−/HCO3− transporters, which exchange intracellular HCO3− for extracellular Cl− and thereby lower the intracellular pH. They are ubiquitously expressed in vertebrate tissues. It has been shown that the purinergic agonist ATP triggers activation of anion exchange. ATP induces tyrosine phosphorylation of AE1, activation of SFKs such as Fyn, and association of both Fyn and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) with AE1(Fig. 2).92 Inhibition of Src family kinases in vivo prevents purinergic activation of AEs.92 NHE1 activity at the leading edge also results in a more acidic external pH, which modulates integrin-mediated cell–matrix adhesion dynamics and, ultimately, cell migration (Fig. 2).93,94 On the other hand, membrane-enclosed organelles, such as lysosomes, generate an acidic pH required for the dissociation and recycling of endocytosed materials.94

During migration Ca2+ gradients form in the cytosol with lower Ca2+ levels at the leading edge.95 Recent work has demonstrated that lysosomes are also responsible for Ca2+ release.96,97 Ca2+ influx through plasma membrane channels is crucial for repulsion.98 Therefore, we hypothesize that Reelin binds to ApoER2 and VLDLR on migrating neurons, triggers downstream signaling activation including SFKs, PI3K, FAK, PKC, ATP, NHE1 and AE1, eventually resulting in endocytosis of Reelin and its receptor complex. Increased H+ leads to binding of cofilin to PIP2 at the cell membrane. If Reelin and its receptors are endocytosed and sorted to lysosomes, Ca2+ will be released from the lysosomes leading to an increase in Ca2+ in the leading process. Increased intracellular Ca2+ inhibits the migratory process (Fig. 2).99

Reelin induces branching of neurons following migration

We have recently shown that the leading processes of migrating neurons give rise to increasingly more branches once their growth cones get in contact with the Reelin-containing marginal zone. Reeler neurons have fewer braches and are mis-orientated.100 Internalization of Reelin by endocytosis reduces full length Reelin in the matrix; the N-terminal fragment of Reelin is re-secreted after proteolysis. However, this fragment does not bind to Reelin receptors but has a homology to F-spondin.101 Analysis of F-spondin isoforms secreted from transfected cells shows that the core protein without the thrombospondin type 1 repeats is sufficient to promote neuronal differentiation when adsorbed to a surface.102 Whether the remaining active cofilin induces elongation of processes or initiates new branches is much dependent on its relative binding to F-actin103 and its cooperation with the Arp2/3 protein complex.104 However, how reelin regulates process branching still needs to be investigated.

Outlook

There are many molecules that need to be studied in more detail for their specific roles in the migratory process. We suggest taking into account FAK, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase that has been implicated in diverse cellular processes including neuronal migration.105 FAK is located at focal adhesions sites, which are the structures that link the extracellular matrix to the cytoskeleton. Previous work has shown that FAK is dispensable for glial-independent tangential migration of interneurons but is cell-autonomously required for the normal interaction of pyramidal cells with radial glial fibers.105 Loss of FAK function disrupts radial glia–neuron interaction, alters the normal morphology of radially migrating pyramidal cells and increases their tangential dispersion.105 It was recently found that Src controls neuronal migration by regulating the activity of FAK and cofilin.106 Overexpression of the dominant negative form of Src mimics the loss of function induced by decreased FAK phosphorylation at tyrosine residue 925.106 FAK is also phosphorylated at serine 732.107 Since Reelin signaling activates Src, we wonder whether Reelin-deficient reeler mutants show a dysfunction of FAK, for instance, by altered phosphorylation levels at different residues. Finally, we suppose that any factor reducing Reelin expression or altering its signaling pathway during development might result in migration defects and eventually neurological disease.

Abbreviations

- AEs

anion exchangers

- ApoER2

apolipoprotein-E receptor 2

- Arp2/3

actin-related protein 2/3

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- C3G

cyanidin-3-Glucoside

- Dab1

disabled 1

- E

embryonic day

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- GSK

glycogen synthase kinase

- GTP

guanosine-5′-triphosphate

- LIMK1

LIM domain kinase 1

- Lis1

Lissencephaly-1

- MßCD

methyl-ß-cyclodextrin

- NHE1

Na-H exchanger 1

- NPXY

Asn-Pro-X-Tyr

- pH

power of hydrogen

- PH

pleckstrin homology

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PI/PTB

phosphotyrosine interaction (PI) / proteins encoding phosphotyrosine binding (PTB)

- PIs

phosphoinosides

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- P

postnatal day

- Rap1

ras-related protein 1

- SFK

Src family kinase

- SOCS

suppressor of cytokine signaling

- VLDLR

very low-density lipoprotein receptor

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Shanting Zhao (College of Veterinary Medicine, Northwest A&F University, China) for helpful discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FR 620/12-2 and FR 620/14-1 to M.F.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31071873 to S.Z.).

References

- [1].Rakic P. Mode of cell migration to the superficial layers of fetal monkey neocortex. J Comp Neurol 1972; 145:61-83; PMID:4624784; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cne.901450105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Parnavelas JG. The origin and migration of cortical neurones: new vistas. Trends Neurosci 2000; 23(3):126-31; PMID:10675917; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01553-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nadarajah B, Brunstrom JE, Grutzendler J, Wong RO, Pearlman AL. Two modes of radial migration in early development of the cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci 2001; 4:143-50; PMID:11175874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/83967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Berry M, Rogers AW. The migration of neuroblasts in the developing cerebral cortex. J Anat 1965; 99:691-709; PMID:5325778 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mione MC, Cavanagh JF, Harris B, Parnavelas JG. Cell fate specification and symmetrical/asymmetrical divisions in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci 1997; 17:2018-29; PMID:9045730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Malatesta P, Hartfuss E, Götz M. Isolation of radial glial cells by fluorescent-activated cell sorting reveals a neuronal lineage. Development 2000; 127:5253-63; PMID:11076748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kriegstein AR, Götz M. Radial glia diversity: a matter of cell fate. Glia 2003; 43:37-43; PMID:12761864; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/glia.10250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Anthony TE, Klein C, Fishell G, Heintz N. Radial glia serve as neuronal progenitors in all regions of the central nervous system. Neuron 2004; 41:881-90; PMID:15046721; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00140-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Götz M, Barde YA. Radial glial cells defined and major intermediates between embryonic stem cells and CNS neurons. Neuron 2005; 46:369-72; PMID:15882633; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kriegstein AR, Alvarez-Buylla A. The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu Rev Neurosci 2009; 32:149-84; PMID:19555289; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Miyata T, Kawaguchi A, Okano H, Ogawa M. Asymmetric inheritance of radial glial fibers by cortical neurons. Neuron 2001; 31(5):727-41; PMID:11567613; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00420-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Curran T, D'Arcangelo G. Role of reelin in the control of brain development. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 1998; 26:285-94; PMID:9651544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jossin Y, Bar I, Ignatova N, Tissir F, De Rouvroit CL, Goffinet AM. The reelin signaling pathway: some recent developments. Cereb Cortex 2003a; 13:627-33; Review; PMID:12764038; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/cercor/13.6.627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lavdas AA1, Grigoriou M, Pachnis V, Parnavelas JG. The medial ganglionic eminence gives rise to a population of early neurons in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci 1999; 19:7881-8; PMID:10479690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Marin-Padilla M. Cajal-Retzius cells and the development of the neocortex. Trends Neurosci 1998; 21:64-71; PMID:9498301; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01164-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bielle F, Griveau A, Narboux-Nême N, Vigneau S, Sigrist M, Arber S, Wassef M, Pierani A. Multiple origins of Cajal-Retzius cells at the borders of the developing pallium. Nat Neurosci 2005; 8:1002-12; PMID:16041369; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nn1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Stewart GR, Pearlman AL. Fibronectin-like immunoreactivity in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci 1987; 7:3325-33; PMID:3668630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].del Río JA, Martínez A, Fonseca M, Auladell C, Soriano E. Glutamate-like immunoreactivity and fate of Cajal-Retzius cells in the murine cortex as identified with calretinin antibody. Cereb Cortex 1995; 5:13-21; PMID:7719127; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/cercor/5.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Caffrey JR, Hughes BD, Britto JM, Landman KA. An in silico agent-based model demonstrates Reelin function in directing lamination of neurons during cortical development. PLoS One 2014; 9(10):e110415; PMID:25334023; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0110415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhao S, Chai X, Förster E, Frotscher M. Reelin is a positional signal for the lamination of dentate granule cells. Development 2004; 131:5117-25; PMID:15459104; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.01387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lambert de Rouvroit C, de Bergeyck V, Cortvrindt C, Bar I, Eeckhout Y, Goffinet AM. Reelin, the extracellular matrix protein deficient in reeler mutant mice, is processed by a metalloproteinase. Exp Neurol 1999; 156:214-7; PMID:10192793; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/exnr.1998.7007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ignatova N, Sindic CJ, Goffinet AM. Characterization of the various forms of the Reelin protein in the cerebrospinal fluid of normal subjects and in neurological diseases. Neurobiol Dis 2004; 15:326-30; PMID:15006702; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jossin Y, Gui L, Goffinet AM. Processing of Reelin by embryonic neurons is important for function in tissue but not in dissociated cultured neurons. J Neurosci 2007; 27(16):4243-52; PMID:17442808; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0023-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jossin Y, Ignatova N, Hiesberger T, Herz J, Lambert de Rouvroit C, Goffinet AM. The central fragment of Reelin, generated by proteolytic processing in vivo, is critical to its function during cortical plate development. J Neurosci 2004; 24:514-21; PMID:14724251; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3408-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Falconer DS. Two new mutants, ‘trembler’ and ‘reeler’, with neurological actions in the house mouse (Mus musculus L.). J Genet 1951; 50:192-201; PMID:24539699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Caviness VS, Jr. Neocortical histogenesis in normal and reeler mice: a developmental study based upon [3H] thymidine autoradiography. Brain Res 1982; 256:293-302; PMID:7104762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kubo K, Nakajima K. Cell and molecular mechanisms that control cortical layer formation in the brain. Keio J Med 2003; 52:8-20; Review; PMID:12713017; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2302/kjm.52.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tissir F, Goffinet AM. Reelin and brain development. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003; 4:496-505; PMID:12778121; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrn1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hack I, Hellwig S, Junghans D, Brunne B, Bock HH, Zhao S, Frotscher M. Divergent roles of ApoER2 and Vldlr in the migration of cortical neurons. Development 2007; 134:3883-91; PMID:17913789; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.005447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chai X, Zhao S, Fan L, Zhang W, Lu X, Shao H, Wang S, Song L, Failla AV, Zobiak B, Mannherz HG, Frotscher M. Reelin and cofilin cooperate during the migration of cortical neurons: a quantitative morphological analysis. Development 2016; 143(6):1029-40; PMID:26893343; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.134163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Trommsdorff M, Gotthardt M, Hiesberger T, Shelton J, Stockinger W, Nimpf J, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Herz J. Reeler/Disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knockout mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2. Cell 1999; 97(6):689-701; PMID:10380922; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80782-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].D'Arcangelo G, Homayouni R, Keshvara L, Rice DS, Sheldon M, Curran T. Reelin is a ligand for lipoprotein receptors. Neuron 1999; 24:471-9; PMID:10571240; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80860-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hiesberger T, Trommsdorff M, Howell BW, Goffinet A, Mumby MC, Cooper JA, Herz J. Direct binding of Reelin to VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of disabled-1 and modulates tau phosphorylation. Neuron 1999; 24:481-9; PMID:10571241; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80861-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yasui N, Nogi T, Kitao T, Nakano Y, Hattori M, Takagi J. Structure of a receptor-binding fragment of reelin and mutational analysis reveal a recognition mechanism similar to endocytic receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:9988-93. PMID:17548821; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0700438104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Howell BW, Lanier LM, Frank R, Gertler FB, Cooper JA. The disabled 1 phosphotyrosine-binding domain binds to the internalization signals of transmembrane glycoproteins and to phospholipids. Mol Cell Biol 1999; 19:5179-88; PMID:10373567; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.19.7.5179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Benhayon D, Magdaleno S, Curran T. Binding of purified Reelin to ApoER2 and VLDLR mediates tyrosine phosphorylation of Disabled-1. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2003; 112:33-45; PMID:12670700; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0169-328X(03)00032-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Rakic P, Caviness VS Jr. Cortical development: view from neurological mutants two decades later. Neuron 1995; 14:1101-4; PMID:7605626; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90258-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sheldon M, Rice DS, D'Arcangelo G, Yoneshima H, Nakajima K, Mikoshiba K, Howell BW, Cooper JA, Goldowitz D, Curran T. Scrambler and yotari disrupt the disabled gene and produce a reeler-like phenotype in mice. Nature 1997; 389(6652):730-3; PMID:9338784; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/39601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Walsh CA, Goffinet AM. Potential mechanisms of mutations that affect neuronal migration in man and mouse. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2000; 10:270-4; Review; PMID:10826984; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00076-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Drakew A, Deller T, Heimrich B, Gebhardt C, Del Turco D, Tielsch A, Förster E, Herz J, Frotscher M. Dentate granule cells in reeler mutants and VLDLR and ApoER2 knockout mice. Exp Neurol 2002; 176:12-24; PMID:12093079; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/exnr.2002.7918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Schmid RS, Anton ES. Role of integrins in the development of the cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex 2003; 13:219-24. Review. PMID:12571112; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/cercor/13.3.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schmid RS, Jo R, Shelton S, Kreidberg JA, Anton ES. Reelin, integrin and DAB1 interactions during embryonic cerebral cortical development. Cereb Cortex 2005; 15:1632-6; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dulabon L, Olson EC, Taglienti MG, Eisenhuth S, McGrath B, Walsh CA, Kreidberg JA, Anton ES. Reelin binds alpha3beta1 integrin and inhibits neuronal migration. Neuron 2000; 27:33-44; PMID:10939329; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00007-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Graus-Porta D, Blaess S, Senften M, Littlewood-Evans A, Damsky C, Huang Z, Orban P, Klein R, Schittny JC, Müller U. Beta1-class integrins regulate the development of laminae and folia in the cerebral and cerebellar cortex. Neuron 2001; 31:367-79. PMID:11516395; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00374-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Frotscher M. Cajal-Retzius cells, Reelin, and the formation of layers. Curr Opin Neurobiol 1998; 8:570-5; Review; PMID:9811621; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0959-4388(98)80082-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chai X, Förster E, Zhao S, Bock HH, Frotscher M. Reelin stabilizes the actin cytoskeleton of neuronal processes by inducing n-cofilin phosphorylation at serine3. J Neurosci 2009; 29:288-99; PMID:19129405; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2934-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Zhao S, Frotscher M. Go or stop? Divergent roles of Reelin in radial neuronal migration. Neuroscientist 2010; 16:421-34; PMID:20817919; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/1073858410367521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hirota Y, Kubo K, Katayama K, Honda T, Fujino T, Yamamoto TT, Nakajima K. Reelin receptors ApoER2 and VLDLR are expressed in distinct spatiotemporal patterns in developing mouse cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol 2015; 523:463-78; PMID:25308109; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cne.23691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Anton ES, Kreidberg JA, Rakic P. Distinct functions of alpha3 and α(v) integrin receptors in neuronal migration and laminar organization of the cerebral cortex. Neuron 1999; 22:277-89; PMID:10069334; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81089-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sanada K, Gupta A, Tsai LH. Disabled-1-regulated adhesion of migrating neurons to radial glial fiber contributes to neuronal positioning during early corticogenesis. Neuron 2004; 42:197-211; PMID:15091337; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00222-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Sekine K, Kawauchi T, Kubo K, Honda T, Herz J, Hattori M, Kinashi T, Nakajima K. Reelin controls neuronal positioning by promoting cell-matrix adhesion via inside-out activation of integrin α5β1. Neuron 2012; 76:353-69; PMID:23083738; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Alcántara S, Ruiz M, D'Arcangelo G, Ezan F, de Lecea L, Curran T, Sotelo C, Soriano E. Regional and cellular patterns of reelin mRNA expression in the forebrain of the developing and adult mouse. J Neurosci 1998; 18:7779-99; PMID:9742148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Schiffmann SN, Bernier B, Goffinet AM. Reelin mRNA expression during mouse brain development. Eur J Neurosci 1997; 9:1055-71; PMID:9182958; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01456.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kawauchi T, Sekine K, Shikanai M, Chihama K, Tomita K, Kubo K, Nakajima K, Nabeshima Y, Hoshino M. Rab GTPases-dependent endocytic pathways regulate neuronal migration and maturation through N-cadherin trafficking. Neuron 2010; 67:588-602; PMID:20797536; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Jossin Y, Cooper JA. Reelin, Rap1 and N-cadherin orient the migration of multipolar neurons in the developing neocortex. Nat Neurosci 2011; 14:697-703; PMID:21516100; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nn.2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Franco SJ, Martinez-Garay I, Gil-Sanz C, Harkins-Perry SR, Müller U. Reelin regulates cadherin function via Dab1/Rap1 to control neuronal migration and lamination in the neocortex. Neuron 2011; 69:482-97; PMID:21315259; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gärtner A, Fornasiero EF, Munck S, Vennekens K, Seuntjens E, Huttner WB, Valtorta F, Dotti CG. N-cadherin specifies first asymmetry in developing neurons. EMBO J 2012; 31:1893-903; PMID:22354041; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2012.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Gil-Sanz C, Franco SJ, Martinez-Garay I, Espinosa A, Harkins-Perry S, Müller U. Cajal-Retzius cells instruct neuronal migration by coincidence signaling between secreted and contact-dependent guidance cues. Neuron 2013; 79:461-77; PMID:23931996; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Kubo K, Mikoshiba K, Nakajima K. Secreted Reelin molecules form homodimers. Neurosci Res 2002; 43:381-8; PMID:12135781; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0168-0102(02)00068-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Strasser V, Fasching D, Hauser C, Mayer H, Bock HH, Hiesberger T, Herz J., Weeber EJ, Sweatt JD, Pramatarova A, et al.. Receptor clustering is involved in Reelin signaling. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24:1378-86; PMID:14729980; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1378-1386.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Bock HH, Jossin Y, May P, Bergner O, Herz J. Apolipoprotein E receptors are required for reelin-induced proteasomal degradation of the neuronal adaptor protein Disabled-1. J Biol Chem 2004; 279:33471-9; PMID:15175346; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M401770200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Duit S, Mayer H, Blake SM, Schneider WJ, Nimpf J. Differential functions of ApoER2 and very low density lipoprotein receptor in Reelin signaling depend on differential sorting of the receptors. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:4896-908; PMID:19948739; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M109.025973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Riddell DR, Sun XM, Stannard AK, Soutar AK, Owen JS. Localization of apolipoprotein E receptor 2 to caveolae in the plasma membrane. J Lipid Res 2001; 42:998-1002; PMID:11369809 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Mayer H, Duit S, Hauser C, Schneider WJ, Nimpf J. Reconstitution of the Reelin signaling pathway in fibroblasts demonstrates that Dab1 phosphorylation is independent of receptor localization in lipid rafts. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26:19-27; PMID:16354676; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.26.1.19-27.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Koch S, Strasser V, Hauser C, Fasching D, Brandes C, Bajari TM, Schneider WJ, Nimpf J. A secreted soluble form of ApoE receptor 2 acts as a dominant-negative receptor and inhibits Reelin signaling. EMBO J 2002; 21:5996-6004; PMID:12426372; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/cdf599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Howell BW, Hawkes R, Soriano P, Cooper JA. Neuronal position in the developing brain is regulated by mouse disabled-1. Nature 1997a; 389:733-7; PMID:9338785; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/39607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Howell BW, Gertler FB, Cooper JA. Mouse disabled (mDab1): a Src binding protein implicated in neuronal development. EMBO J 1997b; 16:1165-75; PMID:9009273; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/16.1.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Feng L, Allen NS, Simo S, Cooper JA. Cullin 5 regulates Dab1 protein levels and neuron positioning during cortical development. Genes Dev 2007; 21:2717-30; PMID:17974915; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1604207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Sekine K, Honda T, Kawauchi T, Kubo K, Nakajima K. The outermost region of the developing cortical plate is crucial for both the switch of the radial migration mode and the Dab1-dependent “inside-out” lamination in the neocortex. J Neurosci 2011; 31:9426-39; PMID:21697392; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0650-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Kerjan G, Gleeson JG. A missed exit: Reelin sets in motion Dab1 polyubiquitination to put the break on neuronal migration. Genes Dev 2007; 21:2850-4; PMID:18006681; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1622907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Gotthardt M, Trommsdorff M, Nevitt MF, Shelton J, Richardson JA, Stockinger W, Nimpf J, Herz J. Interactions of the low density lipoprotein receptor gene family with cytosolic adaptor and scaffold proteins suggest diverse biological functions in cellular communication and signal transduction. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:25616-24; PMID:10827173; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M000955200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Morimura T, Hattori M, Ogawa M, Mikoshiba K. Disabled1 regulates the intracellular trafficking of reelin receptors. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:16901-8; PMID:15718228; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M409048200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Bock HH, Jossin Y, Liu P, Förster E, May P, Goffinet AM, Herz J. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase interacts with the adaptor protein Dab1 in response to Reelin signaling and is required for normal cortical lamination. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:38772-9; PMID:12882964; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M306416200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Ohkubo N, Lee YD, Morishima A, Terashima T, Kikkawa S, Tohyama M, Sakanaka M, Tanaka J, Maeda N, Vitek MP, et al.. Apolipoprotein E and Reelin ligands modulate tau phosphorylation through an apolipoprotein E receptor/disabled-1/glycogen synthase kinase-3beta cascade. FASEB J 2003; 17:295-7; PMID:12490540; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1096/fj.02-0434fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Assadi AH, Zhang G, Beffert U, McNeil RS, Renfro AL, Niu S, Quattrocchi CC, Antalffy BA, Sheldon M, Armstrong DD, et al.. Interaction of reelin signaling and Lis1 in brain development. Nat Genet 2003; 35:270-6; PMID:14578885; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Zhang G, Assadi AH, McNeil RS, Beffert U, Wynshaw-Boris A, Herz J, Clark GD, D'Arcangelo G. The Pafah1b complex interacts with the reelin receptor VLDLR. PLoS One 2007; 2:e252; PMID:17330141; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0000252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Sapir T, Elbaum M, Reiner O. Reduction of microtubule catastrophe events by LIS1, platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase subunit. EMBO J 1997; 16:6977-84; PMID:9384577; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Meseke M, Cavus E, Förster E. Reelin promotes microtubule dynamics in processes of developing neurons. Histochem Cell Biol 2013; 139:283-97; PMID:22990595; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00418-012-1025-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Umeshima H, Hirano T, Kengaku M. Microtubule-based nuclear movement occurs independently of centrosome positioning in migrating neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:16182-7; PMID:17913873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Cantrell DA. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signalling pathways. J Cell Sci 2001; 114:1439-45; PMID:11282020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Yang N, Higuchi O, Ohashi K, Nagata K, Wada A, Kangawa K, Nishida E, Mizuno K. Cofilin phosphorylation by LIM-kinase 1 and its role in Rac-mediated actin reorganization. Nature 1998; 393:809-12; PMID:9655398; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/31735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Chinthalapudi K, Rangarajan ES, Patil DN, George EM, Brown DT, Izard T. Lipid binding promotes oligomerization and focal adhesion activity of vinculin. J Cell Biol 2014; 207:643-56; PMID:25488920; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201404128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Voss AK, Britto JM, Dixon MP, Sheikh BN, Collin C, Tan SS, Thomas T. C3G regulates cortical neuron migration, preplate splitting and radial glial cell attachment. Development 2008; 135:2139-49; PMID:18506028; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.016725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].van Rheenen J, Song X, van Roosmalen W, Cammer M, Chen X, Desmarais V, Yip SC, Backer JM, Eddy RJ, Condeelis JS. EGF-induced PtdIns(4,5)P2 hydrolysis releases and activates cofilin locally in carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol 2007; 179:1247-59; PMID:18086920; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200706206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Nagaoka R, Abe H, Obinata T. Site-directed mutagenesis of the phosphorylation site of cofilin: its role in cofilin-actin interaction and cytoplasmic localization. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 1996; 35:200-9; PMID:8913641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Frantz C, Barreiro G, Dominguez L, Chen X, Eddy R, Condeelis J, Kelly MJ, Jacobson MP, Barber DL. Cofilin is a pH sensor for actin free barbed end formation: role of phosphoinositide binding. J Cell Biol 2008; 183:865-79; PMID:19029335; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200804161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Bernstein BW, Painter WB, Chen H, Minamide LS, Abe H, Bamburg JR. Intracellular pH modulation of ADF/cofilin proteins. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 2000; 47:319-36; PMID:11093252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Lee MH, Bell RM. Mechanism of protein kinase C activation by phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate. Biochemistry 1991; 30(4):1041-9; PMID:1846557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Toker A, Meyer M, Reddy KK, Falck JR, Aneja R, Aneja S, Parra A, Burns DJ, Ballas LM, Cantley LC. Activation of protein kinase C family members by the novel polyphosphoinositides PtdIns-3,4-P2 and PtdIns-3,4,5-P3. J Biol Chem 1994; 269:32358-67; PMID:7798235 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Jossin Y, Ogawa M, Metin C, Tissir F, Goffinet AM. Inhibition of SRC family kinases and non-classical protein kinases C induce a reeler-like malformation of cortical plate development. J. Neurosci 2003b; 23:9953-9; PMID:14586026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Ghosh M, Song X, Mouneimne G, Sidani M, Lawrence DS, Condeelis JS. Cofilin promotes actin polymerization and defines the direction of cell motility. Science 2004; 304:743-6; PMID:15118165; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1094561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Pucéat M, Roche S, Vassort G. Src family tyrosine kinase regulates intracellular pH in cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biol 1998; 141:1637-46; PMID:9647655; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Denker SP, Barber DL. Cell migration requires both ion translocation and cytoskeletal anchoring by the Na-H exchanger NHE1. J Cell Biol 2002; 159:1087-96; PMID:12486114; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200208050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Casey JR, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nature 2010; 11:50-61; PMID:19997129; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Brundage RA, Fogarty KE, Tuft RA, Fay FS. Calcium gradients underlying polarization and chemotaxis of eosinophils. Science 1991; 254:703-6; PMID:1948048; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1948048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Patel S, Docampo R. Acidic calcium stores open for business: expanding the potential for intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Trends Cell Biol 2010; 20:277-86; PMID:20303271; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Melchionda M, Pittman JK, Mayor R, Patel S. Ca2+/H+ exchange by acidic organelles regulates cell migration in vivo. J Cell Biol 2016; 212:803-13; PMID:27002171; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201510019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Tojima T, Hines JH, Henley JR, Kamiguchi H. Second messengers and membrane trafficking direct and organize growth cone steering. Nature Rev Neurosci 2011; 12:191-203; PMID:21386859; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrn2996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Horgan AM, Copenhaver PF. G protein-mediated inhibition of neuronal migration requires calcium influx. J Neurosci 1998; 18:4189-200; PMID:9592098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Chai X, Fan L, Shao H, Lu X, Zhang W, Li J, Wang J, Chen S, Frotscher M, Zhao S. Reelin Induces Branching of Neurons and Radial Glial Cells during Corticogenesis. Cereb Cortex 2015; 25:3640-53; PMID:25246510; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/cercor/bhu216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Hibi T, Hattori M. The N-terminal fragment of Reelin is generated after endocytosis and released through the pathway regulated by Rab11. FEBS Lett 2009; 583:1299-303; PMID:19303411; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Schubert D, Klar A, Park M, Dargusch R, Fischer WH. F-spondin promotes nerve precursor differentiation. J Neurochem 2006; 96:444-53; PMID:16300627; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03563.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Andrianantoandro E, Pollard TD. Mechanism of actin filament turnover by severing and nucleation at different concentrations of ADF/cofilin. Mol Cell 2006; 24:13-23; PMID:17018289; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].DesMarais V, Macaluso F, Condeelis J, Bailly M. Synergistic interaction between the Arp2/3 complex and cofilin drives stimulated lamellipod extension. J Cell Sci 2004; 117:3499-510; PMID:15252126; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.01211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Valiente M, Ciceri G, Rico B, Marín O. Focal adhesion kinase modulates radial glia-dependent neuronal migration through connexin-26 J Neurosci 2011; 31:11678-91; PMID:21832197; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2678-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Wang JT, Song LZ, Li LL, Zhang W, Chai XJ, An L, Chen SL, Frotscher M, Zhao ST. Src controls neuronal migration by regulating the activity of FAK and cofilin. Neuroscience 2015; 292:90-100; PMID:25711940; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Ng T, Ryu JR, Sohn JH, Tan T, Song H, Ming GL, Goh EL. Class 3 semaphorin mediates dendrite growth in adult newborn neurons through Cdk5/FAK pathway. PLoS One 2013; 8:e65572; PMID:23762397; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0065572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]