Abstract

Methods are needed to reliably prioritize biologically active driver mutations over inactive passengers in high-throughput cancer sequencing datasets. We present ParsSNP, an unsupervised functional impact predictor that is guided by parsimony. ParsSNP uses an expectation-maximization framework to find mutations that explain tumor incidence broadly, without using pre-defined training labels that can introduce biases. We compare ParsSNP to five existing tools (CanDrA, CHASM, FATHMM Cancer, TransFIC, Condel) across five distinct benchmarks. ParsSNP outperformed the existing tools in 24 out of 25 comparisons. To investigate the real-world benefit of these improvements, ParsSNP was applied to an independent dataset of thirty patients with diffuse-type gastric cancer. It identified many known and likely driver mutations that other methods did not detect, including truncation mutations in known tumor suppressors and the recurrent driver RHOA Y42C. In conclusion, ParsSNP uses an innovative, parsimony-based approach to prioritize cancer driver mutations and provides dramatic improvements over existing methods.

Introduction

As genome sequencing becomes less expensive, there is a pressing need for functional impact scores (FIS) that can computationally prioritize pathogenic mutations for experimental or therapeutic follow-up. The need is especially acute in cancer genomics. Paired tumor-normal sequencing has revealed millions of protein-coding somatic mutations in thousands of patients1, but functional characterization and clinical decision making are stymied by neutral ‘passenger’ mutations that greatly outnumber pathogenic ‘drivers’2.

Many newer FISs predict pathogenic variants using supervised modeling3–5. A model is trained using mutations that are designated as pathogenic or neutral. An advantage of this strategy is that models can be developed for specific tasks by choosing appropriate training data. For instance, curated training data allows CanDrA and CHASM to detect cancer drivers specifically6,7. However, training data also introduces biases that can skew models towards known biology and limit generalizability8. Previously, diverse sources including HGMD, dbSNP, UniProt, COSMIC, and simulated mutations have provided training examples, each requiring assumptions as to what constitutes pathogenic or neutral mutations3–7. In general, supervised modeling may not be tractable if available datasets do not adequately represent the sought-after classes of mutations.

We present a new unsupervised method for identifying driver mutations which is guided by parsimony rather than pre-determined training labels. This approach assumes that drivers are more equitably distributed among samples than passengers; or equivalently, that the proportion of mutations that are drivers drops as tumor mutation rates increase. This assertion follows from previous observations; studies by ourselves and Youn et al demonstrate that cancer genes (which are enriched in driver mutations) are mutated in relatively hypo-mutated tumors more often than chance9,10. More recently, Tomasetti et al showed that cancers depend on a small but consistent number of driver events, over all mutation rates11.

Our goal is to use this knowledge to train a parsimonious model that predicts a few drivers in each patient. We adapt an expectation-maximization (EM) framework to identify a parsimonious set of simple nucleotide polymorphisms that broadly explains cancer incidence in a training set of unlabeled pan-cancer mutations (ParsSNP). We then train a model to identify these putative drivers and detect similar mutations prospectively. This approach should be more generalizable than existing methods since it uses relatively simple assumptions and avoids the need for pre-labeled training data. Additionally, unlike most previous methods, our approach is applicable to all single nucleotide substitutions (including synonymous, nonsynonymous and premature stop mutations) and small frameshift and in-frame insertions/deletions (indels).

We first characterize the process of training ParsSNP. We then use five classification tasks to assess the ability of ParsSNP and other independent tools to detect likely or known driver mutations in pan-cancer and other datasets. We also compare the predictions these tools produce in an independent cancer exome sequencing dataset, representing a typical usage scenario. Finally, we discuss specific driver mutations and genes proposed by ParsSNP.

Results

ParsSNP overview

ParsSNP identifies likely drivers using a training set of unlabeled mutations from a collection of biological samples and two constraints. First, predicted drivers should be few in number and distributed relatively equitably among samples. Second, predicted drivers must be identifiable using the descriptors. Figure 1A provides an overview of ParsSNP, with details in “Online Methods”. There is a learning and application phase.

Figure 1. Overview of ParsSNP and label learning.

A) 1. Label learning begins with a training set of mutations, each belonging to a sample. 2. Descriptors are assigned, and random labels generated (portrayed numbers are illustrative). 3. EM updates labels iteratively such that putative drivers are distributed among samples (E-step) and defined in terms of descriptors (M-step). 4. The final labels and descriptors are used to train a neural network model. 5. The ParsSNP model produces ParsSNP scores when applied to new mutations. B) Distribution of ParsSNP labels after averaging 50 runs (N=566,223). C) Percent contribution of descriptors to ParsSNP scores, using Garson’s algorithm for neural network weights (see text). D) The ParsSNP model was applied to the training and hypermutator pan-cancer sets to produce ParsSNP scores. The fraction of mutations identified as drivers is displayed at various sample mutation burdens and ParsSNP thresholds.

In the learning phase, ParsSNP generates probabilistic driver labels for the training mutations. The labels are initialized with random values from 0 to 1; they are then iteratively refined by expectation-maximization (EM), each step representing a constraint. In the expectation (E) step, each label is updated using Bayes Law and the belief that in a sample with N mutations, between 1 and log2(N) mutations drive tumor growth. Since this range scales logarithmically, the E-step ensures that predicted drivers are uncommon and relatively equitably distributed among samples. The maximization (M) step builds a probabilistic model and updates the labels using the descriptors in cross-validation, ensuring that predicted drivers can always be defined in terms of the descriptors. We use a neural network, since this model produces well scaled probabilities12. The E-step and M-step iterate until convergence.

In the application phase, the refined labels are used to train a final ParsSNP neural network. For clarity, we differentiate between the probabilistic “ParsSNP labels” produced by EM for the training data and the “ParsSNP scores”, which are defined by the model in all datasets (Fig. 1A).

Datasets & Analysis

Our pan-cancer dataset has 1,703,709 protein-coding somatic mutations from 10,239 samples9, broken into three partitions: a 435 sample (851,996 mutation) “hypermutator” set; a 6,536 sample (566,223 mutation) “training” set; and a 3,268 sample (285,490 mutation) “test” set. We also use experimental and germline data. The “driver-dbSNP” dataset has 49,880 common variants from dbSNP plus 1,138 experimentally validated drivers from Kin-Driver13 and Martelotto et al14; the “P53” dataset has 2,314 mutations from the IARC R17 P53 systematic yeast screen15; and the “functional-neutral” dataset has 45 functional and 26 neutral variants drawn from Kim et al, who classified variants with in vitro, in vivo and gene expression data16. Finally, we assess ParsSNP in a typical usage case with the Kakiuchi et al dataset of 30 diffuse-type gastric carcinomas (Supp. Table 1)17. We also make use of the Cancer Gene Census, excluding genes that are only involved in translocations18,19. We use 23 descriptors, including 16 published FISs, plus three mutation-level and four gene-level annotations (further details in “Online Methods”).

Since no “gold standard” for cancer drivers exists, we use the above datasets to assess ParsSNP in five proxy classification tasks (Table 1): 1) Detecting recurrent mutations in the pan-cancer test set (which occur in two or more samples) as important driver proxies6. 2) Detecting pan-cancer test set mutations within CGC members, since mutations in cancer genes are more likely to be drivers. The scope is limited to non-recurrent test set mutations, so as to avoid redundancy with the previous task. 3) Detecting experimentally defined drivers among presumably neutral common germline variants. The driver-dbSNP dataset resembles real world data, in that mutations are drawn from many genes and drivers are rare. 4) Detecting disruptive events (mutant activity <25% of wild type) in the P53 systematic yeast screen. 5) Separating mutations in the functional-neutral dataset16. Although small, this dataset has two unique features: first, functional and neutral variants are validated experimentally; and second, the dataset is curated, with a small number of functional and neutral variants in each of several well-known cancer genes. Note that the training of ParsSNP and control methods does not change task-to-task, and all methods are trained and tested on the same datasets.

Table 1. ParsSNP consistently outperforms existing methods in the classification tasks.

Area-under-receiver-operator-characteristics (AUROC) are shown for ParsSNP and five independent tools which were not used as descriptors. Starred values (*) are significantly worse than the performance achieved by ParsSNP (p<0.05, Delong test). Unstarred values are not statistically significantly different from ParsSNP performance (p>0.05, Delong test).

| AUROCs for Each Classification Task | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrence | CGC | driver-dbSNP | P53 | Functional-Neutral | ||

| Recurrent mutations (present in >1 samples) in the pan-cancer test set. (9,434/173,049) | Mutations in CGC members in the pan-cancer test set (no recurrent mutations). (3,760/169,289) | Experimentally validated drivers against dbSNP common variants. (1,138/49,880) | Disruptive mutants (activity <25% of wild type) in IARC P53 dataset. (475/1,839) | Functional and neutral mutations from Kim et al dataset. (45/26) | Description (Cases/Controls) | |

|

| ||||||

| ParsSNP | 0.656 | 0.833 | 0.975 | 0.843 | 0.834 | NN trained with parsimony and 23 descriptors |

|

| ||||||

| Independent Tools | ||||||

| CanDrA | 0.608* | 0.764* | 0.959* | 0.707* | 0.632* | Reference 6 |

| CHASM | 0.584* | 0.769* | 0.948* | 0.853 | 0.695 | Reference 7 |

| FATHMM Cancer | 0.578* | 0.751* | 0.971 | 0.821* | 0.542* | Reference 20 |

| TransFIC | 0.543* | 0.559* | 0.854* | 0.823* | 0.665* | Reference 21 |

| Condel | 0.543* | 0.608* | 0.918* | 0.839 | 0.661* | Reference 22 |

Our primary performance measure is area-under-receiver-operator-characteristic (AUROC). AUROCs summarize performance across all prediction thresholds and are statistically testable, and were used for these reasons previously7. These values are equivalent to the accuracy of a tool when sorting random pairs consisting of one driver and one passenger (the corresponding error rate of the tool is equal to 1-AUROC). They can range from 0.5 (random classification) to 1.0 (perfect classification; discussed further in “Online Methods”).

For each task, we compare ParsSNP to competing FISs that detect cancer drivers but were not used as descriptors. These “independent tools” include CanDrA, a supervised ensemble method trained to detect recurrent mutations in pan-cancer data6; CHASM, a supervised model trained using curated cancer mutations7; FATHMM Cancer, a Hidden-Markov-Model-based approach20; TransFIC, a method of recalibrating FISs for cancer data (the base score is MutationAssessor, which had the best performance in the original study)21; and Condel, an ensemble method that was not designed specifically for cancer, but was shown by its authors to be useful for detecting drivers22. Each tool was applied using published software (“URLs”). Matching or improving upon the performance of these tools will demonstrate the value of ParsSNP.

ParsSNP Training

An EM approach requires careful empirical testing to ensure it returns an appropriate result. ParsSNP consistently converged within 15–20 iterations (Supp. Fig. 1A). It was highly reproducible, with an average pairwise correlation of 0.99 over 50 runs. Though small, the variations lead us to average the 50 runs for the final labels. They are right-skewed as expected, suggesting a minority of mutations as drivers (Fig. 1B). After training the final ParsSNP model using these labels, we assessed the contribution of descriptors to the neural network using Garson’s algorithm (as described by Olden et al23, Fig. 1C). We find that all descriptors make at least moderate contributions to the model.

ParsSNP is trained such that putative driver mutations should be distributed relatively equitably among samples (i.e. enriched in the least mutated samples, and depleted in hypermutators on a per-mutation basis). We assessed whether ParsSNP scored mutations in this way (Fig. 1D). Mutations from less mutated tumors were more likely to be identified as drivers regardless of ParsSNP threshold; this pattern continues into the hypermutator set, which was not used for training. On average, hypermutators have 23-times more mutations than nonhypermutators (1,958:86.6), but only 5.5 times more mutations with ParsSNP scores over 0.1 (7.17:1.3). At a very stringent cutoff of 0.5, the ratio is only 3.3 (0.23:0.07). Therefore, ParsSNP assigns putative drivers relatively evenly in both the training and held-out hypermutator sets, suggesting that the parsimony-guided training worked as intended.

Both the training data and several tunable parameters may affect algorithm behavior. To test consistency across datasets, we split the training data into two equal halves and found that ParsSNP produced highly correlated scores (r=0.96, Supp. Fig. 1B). We also compared the results of fifteen alternative parameter settings (Supp. Table 2, Supp. Fig. 2). The algorithm consistently converged and usually produced labels that were highly correlated with the reference. We also ran a variety of methodological controls, including simplified and supervised versions of ParsSNP, and gene-level driver detection tools. These controls indicate that ParsSNP’s performance largely derives from its parsimony-based training and descriptor set (particularly the use of gene-level data). This analysis is portrayed in Supp. Table 3, Supp. Figures 3–7, and discussed in-depth in “Online Methods”.

ParsSNP Testing in Pan-Cancer Data

ParsSNP was applied to the withheld test dataset of 3,268 pan-cancer tumors (285,490 mutations). Because the independent tools do not apply to synonymous and truncating mutations, the analysis was limited to 182,483 missense mutations, except where noted.

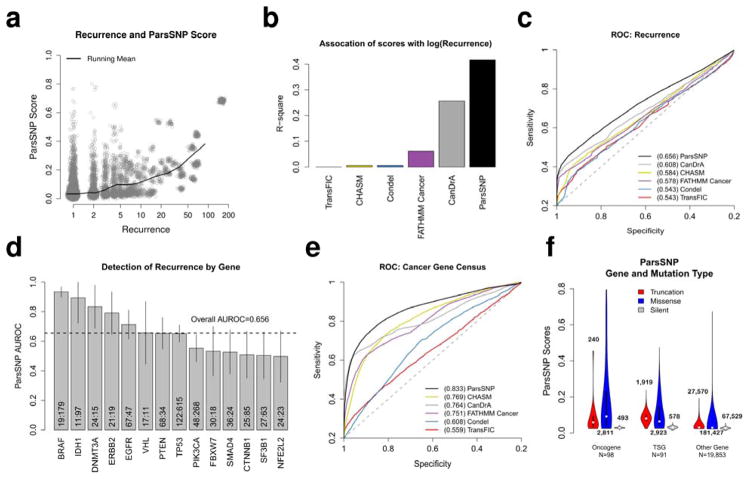

The first classification task was identifying recurrent mutations, since they are often treated as drivers6. ParsSNP scores are positively correlated with mutation recurrence (Fig. 2A), and are more highly associated with recurrence than any of the independent tools (Fig. 2B). Overall, ParsSNP identified 9,434 recurrent missense mutations with AUROC=0.656 (95% CI 0.650–0.663), better than any independent tool (Fig. 2C, Table 1, all Delong p<2.2e-16). CanDrA was the next best (AUROC=0.608, 95% CI 0.601–0.615), which is not surprising considering it was trained with recurrent mutations6. Recurrence also provides an opportunity to assess ParsSNP performance within genes, which is crucial since ParsSNP uses gene-level descriptors and 75% of its variation is between genes (based on sums-of-squares). ParsSNP generally performed as well in single genes as it did in the entire dataset (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. ParsSNP detects recurrent mutations and mutations in known cancer genes in the pan-cancer test set.

A) ParsSNP scores plotted against mutation recurrence for missense mutations (N=182,483). Points are jittered to aid visualization. B) The association of ParsSNP and the independent tools to log(mutation recurrence) for missense mutations, measured by R-square. C) ParsSNP identifies 9,434 recurrent missense mutations better than the independent tools (all Delong tests p<2.2e-16, AUROCs are depicted). D) The ability of ParsSNP to detect recurrent missense mutations in the test set is assessed on a gene-by-gene basis. Portrayed genes must be members of the CGC, have at least 25 missense mutations, and have at least 10 mutations in each class. Mutation counts (non-recurrent:recurrent) and 95% confidence intervals are included for each gene. E) Out of 173,049 non-recurrent missense mutations, ParsSNP identifies the 3,760 which occur in the CGC significantly better than the independent tools (all Delong tests p<2.2e-16, AUROCs are depicted). F) CGC genes were divided into putative oncogenes and putative tumor suppressor genes (TSG) based on the molecular genetic annotation from the CGC dataset (dominant or recessive, respectively). The distribution of ParsSNP scores in the test set is displayed by mutation and gene type, with the number of genes and mutations in each category displayed. ‘Truncation’ events include frameshift, premature stop, nonstop and splice-site changes. ‘Missense’ mutations include missense substitutions as well as inframe insertions/deletions. ‘Silent’ changes include synonymous nucleotide substitutions as well as non-coding variants.

The second classification task was identifying mutations in one of 208 CGC members, which should be enriched in driver events. We limited scope to non-recurrent missense mutations to avoid confounding with the prior analysis. ParsSNP identifies the 3,760 non-recurrent cancer gene mutations with AUROC=0.833 (95% CI 0.825–0.841), better than the independent tools (Fig. 2E, Table 1, all Delong p<2.2e-16).

Unlike the independent tools, ParsSNP applies to mutations besides missense events (“Online Methods”). It is biologically intuitive that there will be an interaction between mutation type and gene type in predicting drivers: we expect that truncations (frameshifts, premature stops) are less likely to be drivers than missense mutations when present in oncogenes, while the opposite is true in tumor suppressor genes (TSG), and silent mutations are unlikely to be drivers regardless of gene type2. We split CGC members into putative oncogenes and TSGs ( “Online Methods”), and found that ParsSNP was able to identify this pattern (Fig. 2F). We questioned which descriptors were responsible, since ParsSNP is not directly aware of gene type. Truncation Rate, which separates oncogenes and TSGs based on rates of truncation events9, showed a marked interaction with mutation type (Supp. Fig. 8A). The ability to detect interactions between the descriptors illustrates the value of using a neural network rather than a simpler model (Supp. Fig. 8B).

Experimental and Germline Data

In our third classification task, we assessed ParsSNP’s performance in the driver-dbSNP dataset, which combines a large number of (presumably neutral) common germline variants with relatively few experimentally validated drivers. 13,738 genes are mutated at least once in the dataset, and 49 have at least one functional mutation. ParsSNP detected the drivers with AUROC=0.975 (95% CI 0.970–0.981, Fig. 3A), slightly better than FATHMM Cancer (Table 1, Delong p=0.205) and significantly better than the other independent tools (all Delong p<1e-4).

Figure 3. ParsSNP identifies experimentally validated mutations in external datasets.

A) ParsSNP separates 1,138 driver mutations from 49,880 common SNPs in the driver-dbSNP dataset slightly better than FATHMM Cancer (Delong test p=0.205) and significantly better than the other independent tools (all Delong tests p<1e-4, AUROCs are depicted). B) Plot of ParsSNP scores and P53 transactivation activity change for 2,314 mutations in the IARC dataset. C) The association of ParsSNP and the independent tools with log(P53 activity change) is displayed as measured by R-square values. D) ParsSNP identifies 475 disruptive P53 mutations (mutation P53 activity < 25% of wild type) among 2,314 mutations with similar performance to CHASM (Delong test p=0.39) and Condel (Delong test p=0.59), while CanDrA, FATHMM Cancer and TransFIC perform worse (all Delong tests p<0.05, AUROCs are depicted). E) ParsSNP separates 45 experimentally defined functional variants from 26 experimentally defined neutral variants better than existing methods, with Delong test p<0.05 for all except CHASM (Delong test p=0.085).

The fourth classification task focuses on the IARC P53 dataset, which consists of P53 transactivation activity against downstream targets for 2,314 missense mutations15. Like many FISs, ParsSNP ascribes higher scores to mutations that abrogate P53 activity (Fig. 3B). However, ParsSNP is more strongly associated with the P53 fold activity change than any independent tool (Fig. 3C). ParsSNP is a strong performer when identifying the 475 mutations that reduce P53 activity to 25% or less of wild type activity, though it was statistically tied with CHASM (Delong p=0.39) and Condel (Delong p=0.59, Table 1, Fig. 3D).

The final classification task uses the functional-neutral dataset of 71 experimentally validated functional and neutral mutations. ParsSNP markedly outperformed existing methods in this task (AUROC=0.834, 95% CI 0.735–0.933, Fig. 3E, Table 1). The result was significant in the cases of CanDrA, FATHMM Cancer, Condel and TransFIC (all Delong p<0.05), and trending in the case of CHASM, likely due to the limited size of the dataset (CHASM AUROC=0.695, Delong p=0.085).

ParsSNP performance summary

As Table 1 shows, ParsSNP outperforms the independent tools in 24 of 25 comparisons. Moreover, as a summary of accuracy, modest differences in AUROCs can imply large performance gains under particular conditions. For instance, several tools perform the driver-dbSNP task well, often with AUROCs over 0.90. However, since AUROCs of 1.0 represent perfect accuracy, small improvements represent large drops in the AUROC error rate. For example, ParsSNP’s performance in this task (AUROC=0.975) represents more than a two-fold reduction in errors when compared to CHASM (AUROC=0.948). Another valuable consideration is the precision (positive-predictive-value) if only a few predictions can be tested. ParsSNP and CanDrA had the top overall performance in the Recurrence task (AUROCs=0.656 and 0.608, respectively). However, when considering only the top 100 hypotheses from each tool, ParsSNP has a precision of 98% (2 false positives), while CanDrA has a precision of only 84% (16 false positives), an 8-fold increase in errors. These examples illustrate how dramatically ParsSNP reduces errors compared to other methods under typical conditions.

Application of ParsSNP to an Independent Cancer Genome Dataset

We illustrate the advantages of ParsSNP in a typical usage scenario with the Kakiuchi et al dataset of 30 diffuse-type gastric carcinomas (Supp. Table 1)17. We also apply CanDrA and CHASM, the most recently published and the most cited of the independent tools, respectively. We compared the candidate drivers identified by each tool, defining candidates as the top 1% of ranked mutations (30 mutations per tool).

Approximately one third (11/30) of ParsSNP’s candidate drivers are also identified by other methods (Fig. 4). These candidates include missense mutations in well-established cancer genes including PIK3CA, FGFR2 and P53 (gene symbol: TP53). Two thirds of ParsSNP’s candidate drivers (19/30) were not identified by other tools. These mutations include truncations in known TSGs (ARID1A, CDKN2A, SMAD4 and P53)9,24, recurrent mutations (CDC27 Y173S), and confirmed drivers (RHOA Y42C)17. By comparison, mutations uniquely identified by CanDrA included biologically implausible drivers in the very large skeletal muscle proteins titin and dystrophin (TTN and DMD)25 and experimentally confirmed neutral mutations (ERBB2 R678Q)26. Mutations uniquely identified by CHASM were frequently in genes with no known connection to cancer, illustrated by the fact that only 2 of 27 are in CGC members19. Therefore, ParsSNP identifies many likely drivers that other tools do not detect; furthermore, mutations identified exclusively by other tools are often implausible as drivers.

Figure 4. Comparison of candidate driver mutations in an independent dataset reveals known and likely drivers which are only identified by ParsSNP.

ParsSNP, CanDrA and CHASM were applied to the Kakiuchi et al dataset, which consists of 2,988 protein-coding somatic mutations from 30 diffuse-type gastric carcinoma patients. For each tool, the top 30 predicted drivers (equivalent to 1% of the dataset) were extracted. The overlap between the candidate driver lists from each tool is diagramed (top left), and the candidate drivers themselves are listed according to the tools they were identified by.

We also explored the Kakiuchi et al dataset on a per-patient basis, since FISs will frequently be used in this fashion as it becomes common to exome-sequence clinical cases. We focus on patients 313T, 319T, and 361T, who had many predicted drivers in well-known cancer genes. Table 2 shows the top five candidate drivers identified by ParsSNP, CanDrA and CHASM in each patient. In patient 313T, ParsSNP correctly identifies RHOA Y42C, and also suggests PIK3CA H1047L (H1047R is a confirmed driver27) and a truncation in the tumor suppressor ARID1A. Of these three plausible drivers, CanDrA and CHASM only identify the PIK3CA mutation. In patient 319T, ParsSNP identifies several truncations in known tumor suppressors SMAD4, ARID1A and P53, which the other tools miss since they do not apply to truncations. ParsSNP also informatively suggests that these truncations are more likely to be drivers than the R56C mutation in the cancer gene BAP19. In patient 361T, ParsSNP identifies missense mutations in the known cancer genes P53, FGFR2 and NOTCH2, as well as a truncation in the tumor suppressor CDKN2A19. Of these, CanDrA and CHASM only identify the P53 and FGFR2 mutations. However, they also identify an implausible candidate driver in dystrophin (DMD R137Q)25. We conclude that ParsSNP identifies candidate drivers that are more biologically plausible than those produced by competing methods, both across whole datasets and within individual patients.

Table 2. ParsSNP identifies known and likely driver mutations that are not detected by other methods in individual patients.

For patients 313T, 319T and 361T from the Kakiuchi et al study, the top five predicted drivers are shown as determined by ParsSNP, CanDrA and CHASM.

ParsSNP and Novel Driver Identification

Another use of ParsSNP is to identify biological hypotheses. We pooled ParsSNP scores for the hypermutator, training and test sets. To narrow focus, we considered only the 75 unique mutations with ParsSNP scores over 0.5 (Supp. Table 4). They include recurrent driver mutations in BRAF (V600E), IDH1 (R132C/L) and NRAS (Q61R), but 54/75 mutations are not recurrent, including the top three: CTNNB1 P687L (ParsSNP=0.795), NRAS E153A (0.789), and CTNNB1 F777S (0.787). Most of the mutations are within CGC members, but thirteen are not: two are in TATA-binding protein (TBP A191T and R168Q) and three are in a calcium-dependent potassium channel (KCNN3 R435C, L413Q and S517Y). Moreover, TBP and KCNN3 have generally elevated ParsSNP scores by one-sample Wilcoxon test (Supp. Fig. 9, Supp. Table 5, Bonferroni p<0.05). Taken together, ParsSNP suggests these genes as putative cancer genes, with TBP A191T and R168Q, and KCNN3 R435C, L413Q and S517Y as the most promising driver mutations.

We also examined the differences in ParsSNP scores between hypermutators and non-hypermutators (training and test). While many genes have elevated scores exclusively in the nonhypermutators, none could be detected in only the hypermutators (Supp. Fig. 10A). However, a differential functionality analysis on a per-gene basis (Supp. Fig. 10B) highlighted two genes: RNF43 (a ubiquitin ligase28) and UPF3A (involved in nonsense mediated decay29) have modestly but significantly elevated ParsSNP scores in the hypermutated samples, suggesting that they may play a role in hypermutator biology.

Discussion

It is likely that only a small fraction of mutations identified by cancer genome sequencing are drivers2,11, making it difficult to direct experimental and clinical decision-making. FISs can filter out passengers, but shortcomings include limited generalizability due to biases from pre-labeled training data. ParsSNP avoids the use of pre-labeled training data by using parsimony to generate its own labels. This requires that putative drivers be 1) relatively equitably distributed among samples, which is the basis of the E-step, and 2) definable in terms of the descriptors, which is enforced by the M-step. Using these constraints, we found a single set of labels in the training pan-cancer set, and trained a model to generate ParsSNP scores.

The assessment of ParsSNP required careful design. A central motivation for this study is the lack of a “gold standard” for defining drivers and passengers, which would ordinarily be used for both training and assessing a model. While we use parsimony to train ParsSNP, we rely on a series of “silver standards” for assessment, a strategy proposed by Gonzalez-Perez et al21.

We recognize that these tasks have some weaknesses. For example, in the CGC task we defined cancer genes using the Cancer Gene Census, which may be incomplete or biased by manual curation; an automated definition may be equally valid. Tasks relying on experimental data are similarly biased by the choice of model systems and outcome measures. However, the tasks we selected are diverse, with multiple data sources and types, and it is unlikely that the tasks are systematically biased as a whole.

ParsSNP outperformed existing methods in 24 out of 25 comparisons across the five classification tasks. Importantly, no single tool can act as an alternative to ParsSNP across all tasks. That ParsSNP performs very well in all tasks is an extremely important finding, since it suggests that ParsSNP’s performance relative to other tools will be consistent in novel datasets. Although none of these assessments are a gold standard of drivers and passengers, they do resemble datasets that users may assess with ParsSNP and other tools.

To illustrate a typical usage case, we applied ParsSNP to mutations from thirty diffuse-type gastric cancer genomes, and found that it identified known and likely candidate drivers that other methods did not detect. In particular, ParsSNP identified truncation events in tumor suppressors. While methods like CanDrA and CHASM are not designed to work with truncation events, it is clear that they are plausible drivers, and the ability to identify and rank them against missense mutations will be an important feature for users. Based on our results as a whole, we conclude that ParsSNP is superior to existing methods for quickly identifying likely cancer drivers in somatic cancer mutation data.

Many avenues can be explored to improve ParsSNP performance and broaden its applications. Expanding the set of descriptors is one promising possibility: whereas ParsSNP uses 23 descriptors, CHASM had access to 497, and CanDrA had 956. By expanding and modifying the descriptors, the ParsSNP approach can be adapted beyond protein-coding somatic mutations in cancer. For instance, none of the assumptions that underpin ParsSNP are cancer-specific. With some modifications to the descriptors, one can envision a version of ParsSNP that is trained using germline mutations from patients with other polygenic diseases.

More generally, ParsSNP can be applied to problems that lack sufficient training examples for supervised methods. For example, as more patients are whole-genome sequenced, methods to identify non-protein-coding drivers of cancer are needed30. ParsSNP could be well suited to this task, as there are few validated non-protein-coding cancer drivers. ParsSNP’s current descriptors are largely applicable only to protein-coding mutations, but frameworks for defining informative descriptors for non-protein-coding variants already exist4,31. It seems plausible that combining descriptors from these studies with ParsSNP’s training approach could produce models that effectively identify protein- and non-protein-coding drivers.

The identification of pathogenic mutations can guide experimental and clinical decisions. We believe that ParsSNP can aid in this task by leveraging the configuration of mutations within samples to generate more biologically relevant predictions. We demonstrated the strength and generalizability of ParsSNP when detecting driver mutations in cancer using a variety of datasets; moreover, beyond the direct applications we have demonstrated, ParsSNP represents a novel paradigm for the problem of functional impact prediction which can be extended into a wider variety of datatypes than is currently possible.

URLs

Original software, ParsSNP scores and all datasets required to replicate this analysis are available at github.com/Bose-Lab/ParsSNP. Annovar, http://annovar.openbioinformatics.org; Cancer Gene Census, http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/census/; CanDrA, http://bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/main/CanDrA; CHASM, http://www.cravat.us/; FATHMM Cancer, http://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk/cancer.html; TransFIC, http://bg.upf.edu/transfic/home; Condel, http://bg.upf.edu/fannsdb/; MutSigCV, https://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/cga/mutsig; OncodriveCLUST, https://bitbucket.org/bbglab/oncodriveclust/get/0.4.1.tar.gz.

Methods

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

Online Methods

Datasets

We constructed the pan-cancer dataset in a previous study and a full description can be found there9. Mutation data was drawn from the TCGA, ICGC and COSMIC. Data was updated to build hg19 and duplicate data was deleted32. Mutations were annotated with ANNOVAR using RefSeq gene and ljb26 libraries33. The dataset contains 1,703,709 mutations drawn from 10,239 tumors representing 28 cancer types.

In keeping with established practice, we first removed potentially biologically distinct hypermutated samples25,34. Since there is no universal cutoff for defining hypermutation18,34, we used the median mutation burden (715 mutations) to generate two equally sized segments that differ only by mutation rate: 435 samples with 851,996 mutations, and 9,804 samples with 851,713 mutations. The 9,804 non-hypermutated tumors were randomly split 2:1 to generate a 6,536 tumor (566,223 mutation) training dataset and a 3,268 tumor (285,490 mutation) test dataset.

We also apply our models to external data. We drew 2,314 mutations from the IARC R17 systematic P53 yeast screen collection as a benchmarking set15. Like Reva et al, we averaged the normalized scores of all eight downstream targets to reduce technical variation35. We also constructed the “driver-dbSNP” benchmarking dataset from several sources, consisting of: 289 known activating kinase mutations from Kin-Driver13; 849 known non-neutral mutations from Martelotto et al’s recent benchmarking study14, and 49,880 common missense SNPs (minor allele frequency > 1% in human populations) from dbSNP build 142 as presumably non-functional germline mutations. The dbSNP 142 data was gathered from the UCSC Genome Browser on January 14th, 2015. We retrieved all common variants that were annotated as protein-coding in the UCSC internal tables. After re-annotation, there were 49,880 missense mutations. In addition, we make use of 71 experimentally characterized mutations from Kim et al as the “functional-neutral” dataset16. We also drew exome sequencing results from Kakiuchi et al’s study of 30 diffuse-type gastric carcinomas17. Once intergenic and intronic mutations were removed, 2,988 mutations remained in this dataset. All external data was re-annotated and treated the same as our pan-cancer datasets except where noted. Mutations that could not be annotated are excluded.

At several points in the analysis, we make use of the Cancer Gene Census, a curated list of mutations that are associated with cancer19. We further narrow this list with the approach used by Schroeder et al18. Specifically, we remove genes that have only been associated with translocation events, since our dataset does not contain similar events and many of these genes may not be directly associated with cancer. Similarly, we remove genes that have no recorded somatic mutations according to CGC annotations. This leaves 208 genes in the dataset. When we refer to the CGC in the study, we are referring to this reduced set of genes. Where appropriate, we further divide this set into putative oncogenes or tumor suppressors based on their annotated genetic profile (dominant or recessive, respectively)18. Genes with ambiguous profiles are excluded.

Mutation Level Descriptors

ParsSNP uses 20 mutation-level descriptors. Rather than directly train on functional, structural or evolutionary descriptors, ParsSNP incorporates such data indirectly by including 16 previous functional impact scores (FIS) from the ANNOVAR ljb26 libraries33. Details are available through ANNOVAR, but they include established tools such as SIFT, Polyphen2, MutationAssessor, FATHMM, VEST, and CADD, and all are listed in Supp. Table 3. To these we added three additional mutation-level descriptors. Normalized Position is equal to the mutation position divided by the protein length. The Blossum62 score was assigned for amino acid substitutions. The final variable is Mutation Type, which is encoded as two descriptors (VarClassS, VarClassT) that indicate if the mutation is silent (including synonymous, intronic and untranslated mutations) or truncating (including frameshift, splice site, nonstop and nonsense mutations).

Gene Level Descriptors

Four descriptors provide gene-level data. The first is protein length. The rest are drawn from our previous study9. Unaffected Residues tests for the presence of nonrandom mutation recurrence within the gene. Truncation Rate tests for enrichment or depletion of truncation events within a gene. Finally, Cancer Type Distribution tests for genes that are mutated in nonrandom subsets of cancers. We chose these three tests because they are non-redundant with the other information sources available to ParsSNP. These tests were calculated as outlined previously using the training dataset, and applied to additional datasets as annotations.

Imputation and Data Scaling

As our calculations are based on the configuration of mutations within tumors, we cannot simply remove mutations with missing data without removing whole samples and quickly depleting the dataset. Therefore we make use of data imputation at several levels.

Most important is the handling of non-missense mutations, to which many FISs do not apply. We adapted the strategy of OncodriveFM to impute these values36. We consider “truncations” (encompassing nonsense, nonstop, splice site, frameshift and inframe indels) as more likely to be drivers, while we consider “silent” mutations (including synonymous, intronic and untranslated mutations) as less likely. For 9/16 FISs, a classification as functional or neutral is made based on thresholds provided by the original authors33. For each of these impact scores, truncation events with missing values were assigned the average value given to predicted functional mutations. Similarly, silent mutations with missing values were assigned the average value of neutral missense mutations. For tools that had them, intermediate classes were deemed functional. For the seven scores without classification schemes, we used the 95th and 5th percentiles as imputation values for the truncation and silent mutation classes, respectively. ParsSNP results are robust to reasonable changes in the percentiles used.

Remaining missing values are then replaced by mean imputation. Only one of the descriptors had more than 5% missingness in the training set, and none were greater than 10%. Finally, the training set is scaled so that each descriptor is in the range of [0,1], in keeping with best practice for neural network models37. Wherever applicable, descriptors, imputation and scaling values were calculated using the training set and applied to other datasets.

Adapting the Expectation-Maximization Algorithm

The Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm can fit statistical models with missing or latent data38. However, it requires that constraints be placed on the possible solutions. For instance, Zaretzki et al used the EM algorithm to predict atomic sites of P450 metabolism using region-level data, but constrained the number of metabolic sites per region12. In ParsSNP’s learning phase, the missing data is the status of mutations as drivers or passengers, which is constrained so that 1) drivers are relatively equitably distributed among samples, and 2) they are consistent with the descriptors. The E-step will use the first constraint, while the M-step uses the second.

Learning Initialization

ParsSNP begins with descriptors for an unlabeled training set of mutations (X matrix), with each mutation belonging to a biologic sample. ParsSNP uses EM to find a set of labels for the training mutations; more precisely, as a probabilistic model, ParsSNP finds a set of probabilities that describe the unseen, binary driver/passenger labels (we refer to these probabilities as ‘ParsSNP labels’ in the main text). We initialize ParsSNP with a random uniform vector of probabilities. Samples are assigned into equally sized folds that will be used during the M-step throughout the training process, such that mutations never inform their own updates. The probabilities are then iteratively refined by the E and M-steps until they stabilize.

The E-step

The E-step updates probabilities based on the combination of mutations within samples. The probabilities for a given sample (Y) are updated under the belief that the unseen total number of driver mutations in the sample (t) is between a lower (l) and upper (u) bound. Each probability is updated based on the following question: of all the possible configurations of driver/passenger binary labels for the sample in which t is between l and u, what proportion require the mutation be a driver (weighted by probability)?

This can be formalized using Bayes’ Law and some additional definitions. M is the unseen vector of binary mutation labels which sum to t in each sample, while m is the unseen label of the given mutation. Y is the current vector of probabilities, while y is the probability of the given mutation. We denote values that exclude the mutation using prime notation. Given these definitions, the value of y can be updated with the following equation:

While we cannot calculate t and t′ directly, our beliefs regarding the mutation labels M and M′ are described by Y and Y′. Therefore t and t′ can be treated as poisson binomial random variables parameterized by Y and Y′ 39. For each sample in the dataset, Bayes’ Law is applied to each mutation. The poisson binomial cumulative density function is calculated exactly in samples with fewer than 30 mutations and with a refined normal approximation for samples with more39.

The most important parameters in the E-step are the lower and upper bounds. The lower bound is the simpler of the two and is fixed at one driver per sample. A higher value lacks biological justification in cancer, since tumors have been observed with no exomic mutations40. However, setting the lower bound to zero leads the algorithm to converge on a vector of zeroes; this is consistent with the constraint, but non-informative (Supp. Fig. 2, Supp. Table 2).

The upper bound is more complex as the algorithm makes use of two versions. The ‘fixed’ upper bound is defined as log2[mutation burden]. Therefore, a sample with 8 mutations is believed to have between 1 and 3 drivers, while a sample with 1024 is believed to have between 1 and 10 drivers; these ranges illustrate how drivers are presumed to be more equitably distributed than passengers. Using log2 as a function yields reasonable upper bounds over the range of mutation burdens; however, its stringency can cause underflow errors even with double precision arithmetic. The problem most often occurs in very mutated samples in early iterations. Therefore, we define a second, less stringent ‘sliding’ upper bound that is often used initially and is set to some proportion (p) of the total current belief for the sample (default p=0.9). The E-step uses whichever is greater of the sliding and fixed upper bounds. For instance, a sample with 1024 mutations is initialized with a random vector of probabilities, and is therefore currently expected to have ~500 functional mutations on average. The sliding upper bound is p*500=450, while the fixed upper bound is log2(1024)=10. Given the current probabilities, the probability of the total number of drivers being less than 10 is essentially zero, requiring the use of the sliding upper bound. The sliding upper bound applies a consistent, downward pressure on probabilities until the fixed upper bound can be used without risking underflow errors. The algorithm is robust to reasonable alternatives for defining both upper bounds (Supp. Fig. 2, Supp. Table 2).

These concepts are clearer when viewing the E-step code (see ‘URLs’). An important point should be made here however: the upper and lower bounds are “soft” bounds. In the final solution, many samples will be assigned a number of drivers beyond the suggested bounds. While these bounds are important to understanding the behavior of the E-step, in practice any reasonable function for defining these values leads to similar results.

The M-step

The M-step follows a standard machine-learning approach. Samples are assigned to one of five cross-validation folds, which are fixed so that samples never inform their own updates. ParsSNP was robust to changes in the number of folds (Supp. Fig. 2, Supp. Table 2). We fit a single layer neural network to the data, which is capable of producing well-scaled outputs that can be interpreted as probabilities by the E-step and has been used for this reason previously12. The neural network parameters are set by grid search (weight decay [0.1, 0.01, 0.001], size [6, 12, 18]) through bootstrap selection (10 samples of 10,000 mutations each). The cross-validated predicted probabilities are then returned and passed to the E-step if the stop criteria are not satisfied.

Algorithm Stop and Model Training

The algorithm ends once the vector of mutation probabilities stabilizes. We define stabilization as a mean-square difference (MSD) between iterations of less than 1e-5, or a change in MSD of less than 5% between iterations. In practice, the second relative cut-off was invoked more often than the absolute cut-off, but the algorithm consistently converged by 30 iterations even under highly stringent cut-offs.

Once the algorithm ends, we have a vector of probabilities for the training data that optimally meets our constraints, and are interpreted by ParsSNP as the probability of each mutation acting as a driver. These probabilities are the ‘ParsSNP labels’ which we refer to in the main text. As the cross-validation approach we use is non-deterministic, we run the algorithm 50 times and average the final outputs to generate a final result (ParsLR was trained with 50 runs, ParsFIS and ParsNGene were trained with 10 runs, and cancer-specific models were trained with 5 runs; see below for descriptions). The final ParsSNP neural network model is trained with the labels and descriptors using identical settings as the M-step. Note that we could use a different machine learner or even different descriptors at this stage: the EM component of ParsSNP has generated a set of probabilistic labels for the training data, and now the question is one of modeling. The final model is then applied to the various datasets to produce ParsSNP scores.

Methodological Controls

To help understand ParsSNP’s performance, we applied several methodological controls to the classification tasks in addition to the primary ParsSNP model (Supp. Table 3, Supp. Fig. 3–7). Since ParsSNP consists of several components, we include several variations on ParsSNP for comparison. ParsLR uses logistic regression rather than a neural network. ParsFIS uses only the 16 descriptor FISs, while ParsNGene only excludes the three gene-level descriptors from our previous study (Truncation Rate, Unaffected Residues, Cancer Type Distribution)9. For the classification tasks with sufficient data, we also include supervised versions of ParsSNP, which use neural networks and all descriptors but are trained to perform each task directly. The recurrence-trained and CGC-trained models are trained in the pan-cancer training set, and assessed in the test set, with labels defined as they were for the primary ParsSNP model. The driver-dbSNP- and P53-trained models were trained and tested using 10-fold cross validation directly in the corresponding datasets, since we had insufficient data for separate training/test sets in these cases. The model type and tuning procedure is identical to that used in the M-step of ParsSNP’s training. Since ParsSNP incorporates several gene-level descriptors, we ran gene-level tools which are designed to detect cancer genes on the pan-cancer training set and then assessed their performance in the test set (MutSigCV, OncodriveFM, and OncodriveCLUST25,36,41). We also consider CGC membership as a simple approach for defining drivers. Methods that required tuning or training (like the gene-level tools and supervised versions) were trained once on the relevant training data. They were not re-trained or re-tuned for different classification tasks.

We found that using logistic regression (ParsLR) rather than a neural network slightly degraded ParsSNP’s performance in most tasks. We observed that gene-level tools (OncodriveFM, OncodriveCLUST, MutSigCV) generally do not perform well in the tasks when used in isolation; however, removing the gene-level descriptors from ParsSNP does markedly degrade performance in most tasks (ParsFIS, ParsNGene). The only exception was OncodriveCLUST, which performed well in the recurrence task (AUROC=0.72); however, this is not surprising, since it is specifically designed to detect genes with many clustered and recurrent mutations, and should therefore perform well in this particular task. We also found that supervised learning is not as effective as the unsupervised EM training in 15 of 20 comparisons. As expected, supervised models often performed well at the tasks they were trained to perform, but unlike ParsSNP their performance was inconsistent in other tasks. We conclude that the most important source of ParsSNP’s performance is the combination of the novel feature set (particularly the inclusion of gene-level features) with the unsupervised EM training.

Model Improvement

Two possible approaches for improving ParsSNP are to add additional data or focus the model on particular cancer types. Testing ParsSNP on subsets of the training data shows that performance is roughly constant for each classification task until the dataset drops to less than ~250–500 samples (~5–10% of the training data, Supp. Fig. 11).

Since adding pan-cancer data appears unlikely to improve performance, we next considered how narrowing scope to a single cancer type would affect ParsSNP. Versions of ParsSNP were trained and tested in breast, lung adenocarcinoma, melanoma, colorectal adenocarcinoma or head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (cancers with at least 150 patients and 25,000 mutations in the training set, Supp. Table 6). The pan-cancer version of ParsSNP generally outperformed these more targeted models. However, predictions made by cancer-specific and full ParsSNP models were not very correlated, and aggregate performance may mask important differences in predicted drivers. Additional data for these cancer types will clarify if these results are a consequence of noise or true biological differences.

We also explored the use of thresholding to optimize ParsSNP predictions. Since ParsSNP is trained using unlabeled mutations, there is no single objective criterion for setting a ParsSNP threshold. One option is to set thresholds so as to optimize the percentage of samples assigned a number of drivers meeting the E-step boundaries. This approach suggests a cutoff of 0.07 for nonhypermutators, and 0.12 for hypermutators (Supp. Fig. 12A). Alternatively, a threshold could be selected to optimize accuracy in the classification tasks, suggesting a range of 0.08 to 0.16 (Supp. Fig. 12B, Supp. Table 7). While a ParsSNP cutoff of 0.1 may be reasonable in many situations, the observed variations suggest that thresholds be set in a context specific manner, taking into account the relative importance of sensitivity and specificity for the task at hand.

AUROCs

For comparing ParsSNP with alternate strategies, we follow the strategy of Carter et al and use the area-under-receiver-operator-characteristic (AUROC)7. The receiver-operator-characteristic is a curve constructed from the sensitivity and specificity of a classifier at each possible threshold. The area under this curve summarizes classifier performance: a classifier which can achieve perfect sensitivity and specificity simultaneously has AUROC=1, while random guesses should produce AUROC=0.5. AUROCs are advantageous because they encompasses all thresholds simultaneously, while remaining statistically testable42. This maximizes comparability between ParsSNP and the independent tools, which often do not have fixed thresholds (e.g. CHASM), or have recommended thresholds that are meant to optimize performance in datasets that are different from ours. It is important to note that we have not used thresholded predictions from the independent tools: unless otherwise noted, all tools are assessed based on their raw scores, even when the original authors provide thresholds. In practice of course, users may want to apply thresholds to ParsSNP to improve interpretability. We recommend that thresholds be set in a context specific manner, taking into account the relative need for sensitivity and specificity, and the relative costs of false positives or negatives.

Statistics and Software

ROC curves were compared using Delong tests for correlated or paired data42. Gene-to-gene comparisons were made using Wilcoxon one- or two-sample tests. All tests were two-sided unless otherwise noted. Multiple comparisons were Bonferroni corrected unless otherwise noted.

All analyses and calculations were performed in 64-bit R version 3.1 using double precision arithmetic. Poisson binomial distributions were calculated with the ‘poibin’ R package 39, while neural networks were fitted and tuned using functions from the ‘nnet’ and ‘e1071’ packages 43. ROC analysis were performed with the ‘pROC’ package44.

CanDrA, CHASM, FATHMM Cancer, TransFIC and Condel, MutSigCV and OncodriveCLUST were applied to our datasets using the software made available through the original publications (see “URLs”). Oncodrive-fm was re-implemented in R according to the protocol in the original publication.

Code Availability

Original software, ParsSNP scores and all datasets used in the study are available at github.com/Bose-Lab/ParsSNP.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. ParsSNP convergence and reproducibility. A) The EM portion of ParsSNP consistently converges in 15–20 iterations. Lines are offset slightly to aid visualization. B) The pan-cancer training set was partitioned randomly into two equally sized, independent halves. ParsSNP produces highly correlated scores when trained on independent but comparable datasets (N=566,223).

Supplementary Figure 2: Comparison of reference and parameter variations during learning. The results of various alternative parameter settings are plotted against the reference labels in the training dataset (N=566,223, see Supp. Table 2 for summary statistics). Most alternative settings produce predictions that are highly correlated with the default settings. Key: ELOG1.1, E-step uses a logarithmic upper-bound with base of 1.1 (default=2); ELOG10, logarithm base is 10; ECONSTANT3, E-step uses a constant upper-bound set to 3 (default upper-bound scales logarithmically in base 2); ECONSTANT10, constant upper bound of 10; ECONSTANT20, constant upper-bound of 20; EFLOOR0, E-step lower-bound set to 0 (default=1); EFLOOR5, lower-bound set to 5; E3to10, E-step uses lower and upper bounds of 3 and 10 for all samples; ESTEP0.8, E-step sliding bound calculated as 80% of current belief (default=90%); ESTEP0.95, sliding bound calculated as 95% of current belief; MCV2, M-step uses 2-fold cross validation (default=5); LOGISTIC, M-step uses logistic regression (default is a tuned neural network); NODES6, M-step uses neural network with only 6 hidden nodes (default is tuned, can use more than 6 nodes); DECAY0.1, M-step uses neural network with weight decay of 0.1 (default is tuned, can use less stringent decay); DECAY0.1; NODES6, M-step enforces use of a simpler neural network than default settings require.

Supplementary Figure 3. Performance in detecting recurrent missense mutations in the pan-cancer test set. Control ROC curves, related to Supp. Table 3, column 1. AUROCs are depicted.

Supplementary Figure 4. Performance in detecting non-recurrent mutations in CGC members in the pan-cancer test set. Control ROC curves, related to Supp. Table 3, column 2. AUROCs are depicted.

Supplementary Figure 5. Performance in detecting driver mutations in the driver-dbSNP dataset. Control ROC curves, related to Supp. Table 3, column 3. AUROCs are depicted.

Supplementary Figure 6. Performance in detecting disruptive mutations in IARC P53 dataset. Control ROC curves, related to Supp. Table 3, column 4. AUROCs are depicted.

Supplementary Figure 7. Performance in the functional-neutral dataset. Control ROC curves, related to Supp. Table 3, column 5. AUROCs are depicted.

Supplementary Figure 8. ParsSNP score boxplots by mutation and gene type. A) Truncation rate is a gene-level descriptor that assigns low p-values to genes enriched in truncations (TSG-like) and assigns high p-values to genes that are depleted in truncations (ONC-like). ‘Truncation’ events include frameshift, pre mature stop and nonstop changes. ‘Missense’ mutations include missense substitutions as well as inframe insertions/deletions. ‘Silent’ changes include synonymous nucleotide substitutions as well as non-coding variants. Truncations receive higher median scores in TSG-like genes, while missense mutations receive higher scores in both TSG-like and ONC-like genes. This represents a potential non-linear two-way interaction between ParsSNP descriptors (Truncation Rate and mutation type). Boxes enclose the inter-quartile range. B) ParsLR uses Logistic Regression rather than a neural network model, and does not exhibit the same properties as the full ParsSNP model.

Supplementary Figure 9. Identification of putative driver genes and mutations. Genes are plotted by the average ParsSNP score of their mutations and their single highest score in the entire pan-cancer dataset (training+test+hypermutator). The top ParsSNP scoring mutations are generally found in members of the CGC. Two genes not belonging to the CGC have multiple exceptional mutations (arrows): TATA Box Binding Protein (TBP), and the calcium-activated potassium channel, KCNN3. Both have significantly higher median ParsSNP scores than expected by chance (Bonferroni corrected one-sample Wilcoxon p<0.05) and multiple mutations with exceptionally high ParsSNP scores, including: TBP A191T (ParsSNP=0.75) and R168Q (0.67), as well as KCNN3 R435C (0.60), L413Q (0.59), S517Y (0.53).

Supplementary Figure 10. Differential functionality between hypermutated and non-hypermutated samples. A) A one-sample Wilcoxon test was performed on each gene in both the hypermutated and non-hypermutated (training + test) portions of the dataset using internal null distributions. The −log10 p-values of these tests are shown. As expected, many well-known cancer genes were more easily detected in the non-hypermutators. No genes were observed with elevated ParsSNP scores exclusively in the hypermutators. B) A two-sample Wilcoxon test was performed for each gene, comparing the ParsSNP scores assigned to it in the hypermutated and non-hypermutated segments. Genes are plotted by the magnitude of median shift (negative values indicate lower scores in the hypermutated samples) and the −log10 p-value. This analysis indicates that mutations in RNF43 and UPF3A have modestly but significantly elevated scores when observed in hypermutators. This suggests that these genes may be involved in the unique biology of these tumors.

Supplementary Figure 11. ParsSNP performance and dataset size. ParsSNP models were trained on progressively smaller subsets of the pan-cancer training data (N=566,223), and performance (AUROC) assessed for each classification task. Points represent average performance of 5 replicates.

Supplementary Figure 12. Criteria for thresholding ParsSNP scores. A) The E-step constraints are one possible objective criterion for thresholding ParsSNP scores. The value to be optimized is the percentage of samples receiving a number of driver mutations that is compatible with the E-step upper and lower bounds under the proposed threshold. B) Another approach is to select a threshold that optimizes accuracy (correct classification rate) in the classification tasks.

Supplementary Table 1. Kakiuchi mutations.

Supplementary Table 2. Parameter variation.

Supplementary Table 3. AUROCs of all strategies.

Supplementary Table 4. Exceptional mutations.

Supplementary Table 5. Cancer gene analysis.

Supplementary Table 6. Specific Cancer Types.

Supplementary Table 7. Thresholding and Performance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Obi L. Griffith for critically reading the manuscript. Our work was supported by the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center, the ‘Ohana Breast Cancer Research Fund, the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital (to RB), the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health (R01LM012222 to S.J.S.), and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (DFS-134967 to R.D.K.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

RDK and SJS designed the study. RDK wrote software and performed the analysis. RDK, SJS and RB wrote the manuscript. RB supervised the project.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Forbes SA, et al. COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:D945–D950. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelstein B, et al. Cancer Genome Landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter H, Douville C, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, Karchin R. Identifying Mendelian disease genes with the variant effect scoring tool. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(Suppl 3):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-S3-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kircher M, et al. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nature genetics. 2014;46:310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adzhubei IA, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mao Y, et al. CanDrA: Cancer-Specific Driver Missense Mutation Annotation with Optimized Features. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e77945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter H, et al. Cancer-specific high-throughput annotation of somatic mutations: computational prediction of driver missense mutations. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6660–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ionita-Laza I, McCallum K, Xu B, Buxbaum JD. A spectral approach integrating functional genomic annotations for coding and noncoding variants. Nat Genet. 2016;48:214–220. doi: 10.1038/ng.3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar RD, Searleman AC, Swamidass SJ, Griffith OL, Bose R. Statistically Identifying Tumor Suppressors and Oncogenes from Pan-Cancer Genome Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3561–3568. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youn A, Simon R. Identifying cancer driver genes in tumor genome sequencing studies. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:175–181. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomasetti C, Marchionni L, Nowak MA, Parmigiani G, Vogelstein B. Only three driver gene mutations are required for the development of lung and colorectal cancers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112:118–123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421839112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaretzki JM, Browning MR, Hughes TB, Swamidass SJ. Extending P450 site-of-metabolism models with region-resolution data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1966–73. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simonetti FL, Tornador C, Nabau-Moreto N, Molina-Vila MA, Marino-Buslje C. Kin-Driver: a database of driver mutations in protein kinases. Database (Oxford) 2014;2014:bau104. doi: 10.1093/database/bau104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martelotto LG, et al. Benchmarking mutation effect prediction algorithms using functionally validated cancer-related missense mutations. Genome Biol. 2014;15:484. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0484-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petitjean A, et al. Impact of mutant p53 functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53 database. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:622–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim E, et al. Systematic Functional Interrogation of Rare Cancer Variants Identifies Oncogenic Alleles. Cancer Discovery. 2016;6:714–726. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kakiuchi M, et al. Recurrent gain-of-function mutations of RHOA in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:583–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroeder MP, Rubio-Perez C, Tamborero D, Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N. OncodriveROLE classifies cancer driver genes in loss of function and activating mode of action. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:i549–55. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Futreal PA, et al. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shihab HA, Gough J, Cooper DN, Day IN, Gaunt TR. Predicting the functional consequences of cancer-associated amino acid substitutions. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1504–10. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez-Perez A, Deu-Pons J, Lopez-Bigas N. Improving the prediction of the functional impact of cancer mutations by baseline tolerance transformation. Genome Med. 2012;4:89. doi: 10.1186/gm390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N. Improving the assessment of the outcome of nonsynonymous SNVs with a consensus deleteriousness score, Condel. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:440–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olden JD, Jackson DA. Illuminating the “black box”: a randomization approach for understanding variable contributions in artificial neural networks. Ecological modelling. 2002;154:135–150. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan B, Wang TL, Shih IM. ARID1A, a Factor That Promotes Formation of SWI/SNF-Mediated Chromatin Remodeling, Is a Tumor Suppressor in Gynecologic Cancers. Cancer Research. 2011;71:6718–6727. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence MS, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499:214–8. doi: 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bose R, et al. Activating HER2 Mutations in HER2 Gene Amplification Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Discovery. 2013;3:224–237. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang S, Bader AG, Vogt PK. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mutations identified in human cancer are oncogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:802–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408864102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koo BK, et al. Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature. 2012;488:665–669. doi: 10.1038/nature11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim VN, Kataoka N, Dreyfuss G. Role of the nonsense-mediated decay factor hUpf3 in the splicing-dependent exon-exon junction complex. Science. 2001;293:1832–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1062829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang FW, et al. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339:957–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1229259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee D, et al. A method to predict the impact of regulatory variants from DNA sequence. Nat Genet. 2015;47:955–961. doi: 10.1038/ng.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujita PA, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: update 2011. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:D876–D882. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:e164–e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kandoth C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reva B, Antipin Y, Sander C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: application to cancer genomics. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:e118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N. Functional impact bias reveals cancer drivers. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40:e169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Basheer IA, Hajmeer M. Artificial neural networks: fundamentals, computing, design, and application. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2000;43:3–31. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(00)00201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1977:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong Y. On computing the distribution function for the sum of independent and nonidentical random indicators. Dep Statit, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA, Tech Rep 11_2. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Network T.C.G.A.R. Genomic and Epigenomic Landscapes of Adult De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamborero D, Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N. OncodriveCLUST: exploiting the positional clustering of somatic mutations to identify cancer genes. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2238–2244. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern applied statistics with S. Springer Science & Business Media; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robin X, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. ParsSNP convergence and reproducibility. A) The EM portion of ParsSNP consistently converges in 15–20 iterations. Lines are offset slightly to aid visualization. B) The pan-cancer training set was partitioned randomly into two equally sized, independent halves. ParsSNP produces highly correlated scores when trained on independent but comparable datasets (N=566,223).

Supplementary Figure 2: Comparison of reference and parameter variations during learning. The results of various alternative parameter settings are plotted against the reference labels in the training dataset (N=566,223, see Supp. Table 2 for summary statistics). Most alternative settings produce predictions that are highly correlated with the default settings. Key: ELOG1.1, E-step uses a logarithmic upper-bound with base of 1.1 (default=2); ELOG10, logarithm base is 10; ECONSTANT3, E-step uses a constant upper-bound set to 3 (default upper-bound scales logarithmically in base 2); ECONSTANT10, constant upper bound of 10; ECONSTANT20, constant upper-bound of 20; EFLOOR0, E-step lower-bound set to 0 (default=1); EFLOOR5, lower-bound set to 5; E3to10, E-step uses lower and upper bounds of 3 and 10 for all samples; ESTEP0.8, E-step sliding bound calculated as 80% of current belief (default=90%); ESTEP0.95, sliding bound calculated as 95% of current belief; MCV2, M-step uses 2-fold cross validation (default=5); LOGISTIC, M-step uses logistic regression (default is a tuned neural network); NODES6, M-step uses neural network with only 6 hidden nodes (default is tuned, can use more than 6 nodes); DECAY0.1, M-step uses neural network with weight decay of 0.1 (default is tuned, can use less stringent decay); DECAY0.1; NODES6, M-step enforces use of a simpler neural network than default settings require.

Supplementary Figure 3. Performance in detecting recurrent missense mutations in the pan-cancer test set. Control ROC curves, related to Supp. Table 3, column 1. AUROCs are depicted.

Supplementary Figure 4. Performance in detecting non-recurrent mutations in CGC members in the pan-cancer test set. Control ROC curves, related to Supp. Table 3, column 2. AUROCs are depicted.

Supplementary Figure 5. Performance in detecting driver mutations in the driver-dbSNP dataset. Control ROC curves, related to Supp. Table 3, column 3. AUROCs are depicted.

Supplementary Figure 6. Performance in detecting disruptive mutations in IARC P53 dataset. Control ROC curves, related to Supp. Table 3, column 4. AUROCs are depicted.

Supplementary Figure 7. Performance in the functional-neutral dataset. Control ROC curves, related to Supp. Table 3, column 5. AUROCs are depicted.

Supplementary Figure 8. ParsSNP score boxplots by mutation and gene type. A) Truncation rate is a gene-level descriptor that assigns low p-values to genes enriched in truncations (TSG-like) and assigns high p-values to genes that are depleted in truncations (ONC-like). ‘Truncation’ events include frameshift, pre mature stop and nonstop changes. ‘Missense’ mutations include missense substitutions as well as inframe insertions/deletions. ‘Silent’ changes include synonymous nucleotide substitutions as well as non-coding variants. Truncations receive higher median scores in TSG-like genes, while missense mutations receive higher scores in both TSG-like and ONC-like genes. This represents a potential non-linear two-way interaction between ParsSNP descriptors (Truncation Rate and mutation type). Boxes enclose the inter-quartile range. B) ParsLR uses Logistic Regression rather than a neural network model, and does not exhibit the same properties as the full ParsSNP model.

Supplementary Figure 9. Identification of putative driver genes and mutations. Genes are plotted by the average ParsSNP score of their mutations and their single highest score in the entire pan-cancer dataset (training+test+hypermutator). The top ParsSNP scoring mutations are generally found in members of the CGC. Two genes not belonging to the CGC have multiple exceptional mutations (arrows): TATA Box Binding Protein (TBP), and the calcium-activated potassium channel, KCNN3. Both have significantly higher median ParsSNP scores than expected by chance (Bonferroni corrected one-sample Wilcoxon p<0.05) and multiple mutations with exceptionally high ParsSNP scores, including: TBP A191T (ParsSNP=0.75) and R168Q (0.67), as well as KCNN3 R435C (0.60), L413Q (0.59), S517Y (0.53).

Supplementary Figure 10. Differential functionality between hypermutated and non-hypermutated samples. A) A one-sample Wilcoxon test was performed on each gene in both the hypermutated and non-hypermutated (training + test) portions of the dataset using internal null distributions. The −log10 p-values of these tests are shown. As expected, many well-known cancer genes were more easily detected in the non-hypermutators. No genes were observed with elevated ParsSNP scores exclusively in the hypermutators. B) A two-sample Wilcoxon test was performed for each gene, comparing the ParsSNP scores assigned to it in the hypermutated and non-hypermutated segments. Genes are plotted by the magnitude of median shift (negative values indicate lower scores in the hypermutated samples) and the −log10 p-value. This analysis indicates that mutations in RNF43 and UPF3A have modestly but significantly elevated scores when observed in hypermutators. This suggests that these genes may be involved in the unique biology of these tumors.