Abstract

Endogenous dopamine (DA) levels at dopamine D2/3 receptors (D2/3R) have been quantified in the living human brain using the agonist radiotracer [11C]-(+)-PHNO. As an agonist radiotracer, [11C]-(+)-PHNO is more sensitive to endogenous DA levels than antagonist radiotracers. We sought to determine the proportion of the variance in baseline [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding to D2/3Rs which can be accounted for by variation in endogenous DA levels. This was done by computing the Pearson’s coefficient for the correlation between baseline binding potential (BPND) and the change in BPND after acute DA depletion, using previously published data. All correlations were inverse, and the proportion of the variance in baseline [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND that can be accounted for by variation in endogenous DA levels across the striatal subregions ranged from 42–59%. These results indicate that lower baseline values of [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND reflect greater stimulation by endogenous DA. To further validate this interpretation, we sought to examine whether these data could be used to estimate the dissociation constant (Kd) of DA at D2/3R. In line with previous in vitro work, we estimated the in vivo Kd of DA to be around 20 nM. In summary, the agonist radiotracer [11C]-(+)-PHNO can detect the impact of endogenous DA levels at D2/3R in the living human brain from a single baseline scan, and may be more sensitive to this impact than other commonly employed radiotracers.

Keywords: AMPT, dopamine, PET, [11C]-(+)-PHNO, D2/3R

1| INTRODUCTION

Over the past 30 years, positron emission tomography (PET) has been used in conjunction with specific radioligands to quantify protein targets and neurochemicals in the living human brain (Gunn, Slifstein, Searle, & Price, 2015). In 1983, the availability of dopamine (DA) D2/3 receptors (D2/3R) was quantified for the first time in the striatum of living humans using [11C]-N-methylspiperone (Wagner et al., 1983). Notably, an earlier attempt in 1979 using [11C]-chlorpromazine failed (Comar et al., 1979). Amidst the ensuing attempts to quantify D2/3R in vivo, it became apparent that certain radiotracers – the substituted benzamides [11C]-raclopride and [123I]-IBZM–could compete with endogenous DA for binding to D2/3R (Laruelle, 2012). For example, unlike the butyrophenone ligands N-[3H]-methylspiperone and [3H]-spiperone, it was found that binding of [3H]-raclopride was reduced by the presence of DA in human and rat striata (Kohler, Hall, Ogren, & Gawell, 1985; Seeman, Guan, & Niznik, 1989). This led to the inference that a portion of potential binding sites for striatal D2/3R were unavailable to [11C]-raclopride in vivo due to the occupancy of those sites by endogenous DA (Seeman, 1988, 1992; Seeman, Niznik, & Guan, 1989; 1990).

The idea that this property could be utilized to quantify synaptic DA levels at D2/3R in vivo appeared as early as 1984 (Friedman, DeJesus, Revenaugh, & Dinerstein, 1984), and led to the proposal of the occupancy model (Laruelle, 2000; Laruelle et al., 1997). Simply, the model predicts that challenges which increase synaptic DA should reduce radiotracer binding to D2/3R, while challenges that reduce synaptic DA should increase binding to D2/3R. Thus, changes in radiotracer binding from a baseline state could be used to quantify DA release and endogenous DA levels at D2/3R, respectively. Using the catecholamine depleting agent alpha-methyl-paratyrosine (α-MPT), baseline endogenous DA levels at D2/3R were quantified for the first time in the striatum of healthy humans using [123I]-IBZM (Laruelle et al., 1997). This was soon followed by studies validating the use of [11C]-raclopride to quantify endogenous DA levels at striatal D2/3R in healthy humans (Verhoeff et al., 2001, 2002, 2003). Using this DA depletion method, invaluable insights have been gained regarding the alteration of endogenous DA in neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, it was discovered that persons with schizophrenia have greater endogenous DA levels at striatal D2/3R compared with healthy controls (Abi-Dargham et al., 2000), specifically in the dorsal caudate (Kegeles et al., 2010). Moreover, not all persons at clinical high-risk for schizophrenia may demonstrate this increase in endogenous striatal DA levels (Bloemen et al., 2013; De Koning et al., 2014), and it is still under investigation whether endogenous DA levels change in the face of chronic stable-antipsychotic treatment (Caravaggio, Nakajima, et al., 2015). Finally, this method has also been used to demonstrate that persons with cocaine-addiction have both reduced D2/3R expression and reduced endogenous DA levels at these receptors throughout the striatum (Martinez et al., 2009).

While efforts have been made to elucidate how baseline D2/3R availability is related to DA synthesis capacity (Ito et al., 2011), it is still unclear to what extent endogenous DA levels influence D2/3R availability at baseline. It has been suggested that the correlation between baseline binding to D2/3R and the change in binding after DA depletion can be used to estimate the magnitude of this influence (Kegeles, Martinez, Slifstein, Laruelle, & Abi-Dargham, 2014). This correlation would indicate the proportion of the variance in baseline D2/3R availability, which can be accounted for by endogenous DA levels (r2). Prima facie, this seems to provide a reasonable estimate of a radioligands’ sensitivity to endogenous DA at baseline. It does so subject to several potential limitations of the α-MPT paradigm, which include that the level of DA depletion is not equivalent across subjects, and that 100% DA depletion is not achievable.

Notably, D2R exist in two distinct conformational states for agonists: a state of high affinity ( ) and a state of low affinity ( ; George et al., 1985; Seeman, 2010; Sibley, D Lean, & Creese, 1982a). In the simplest conceptualization, when D2R are coupled to their intracellular G-protein they are in a high-affinity state, promoting the binding of agonists like DA. When these agonists bind, the G-protein uncouples via guanosine-5′-triphosphate (GTP), initiating an intracellular cascade of second messenger events. Once the G-protein is detached from the D2R, the D2R is in a low-affinity state for DA; DA will prefer to bind again when the G-protein is recycled and re-coupled (Seeman, 2011). Thus, it has been demonstrated in vitro that is the functional state of D2R in the anterior pituitary (George et al., 1985; McDonald, Sibley, Kilpatrick, & Caron, 1984; Sibley et al., 1982) and the striatum (Hamblin, Leff, & Creese, 1984; Richfield, Young, & Penney, 1986; Starke, Reimann, Zumstein, & Hertting, 1978). The consequence of this is that antagonists for D2R should bind with equal affinity to and sites, while agonists like endogenous DA are expected to compete for biding at sites but not sites. Thus, in theory agonist radiotracers for D2R—such as [11C]NPA (Narendran et al., 2004), [11C]MNPA (Finnema et al., 2005), and [11C]-(+)-PHNO (Willeit et al., 2006)—should be more vulnerable to competition by endogenous DA, and label a smaller proportion of the total D2R pool than antagonist radiotracers. For example, in calf caudate membranes agonists show 50 times more affinity for [3H]-DA binding sites over [3H]-haloperidol binding sites; antagonists display about 100 times greater affinity for [3H]-haloperidol binding sites versus [3H]-DA sites (Creese Burt, D. R., & Snyder, 1975). Thus, quantifying endogenous DA levels with an agonist radiotracer may offer a more sensitive and physiologically meaningful measure compared with the use of an antagonist.

We have recently employed the α-MPT PET paradigm to estimate endogenous DA in humans using the agonist radiotracer [11C]-(+)-PHNO (Caravaggio, Raitsin, et al., 2014). This study and others, including competition studies in humans and non-human primates, suggest that agonist radiotracers may be 1.4–1.6 times more sensitive to changes in endogenous DA levels then antagonist radiotracers like [11C]-raclopride (Laruelle, 2012; Narendran et al., 2010; Seneca et al., 2006; Shotbolt et al., 2012). Reanalyzing our previously published α-MPT dataset, we sought to use this correlation approach to estimate the influence of endogenous DA on the baseline D2/3R availability of [11C]-(+)-PHNO. In addition, we used this dataset to estimate free synaptic DA concentration (nM) which in turn was used to estimate the concentration of DA required to occupy half of the striatal D2/3R (i.e., Kd). This was compared to the in vitro literature to validate the estimate of instrasynaptic DA. These results are useful for interpreting the impact of endogenous DA on baseline measurements with [11C]-(+)-PHNO and contribute to our conceptual understanding of the PET occupancy model (Laruelle, 2012).

2 | METHODS

2.1 | α-MPT [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET data

For this investigation, we reanalyzed previously published data using [11C]-(+)-PHNO to estimate endogenous DA levels in the brains of healthy humans using the α-MPT paradigm (Caravaggio, Raitsin, et al., 2014). Ten healthy subjects (4 female; mean age =29.1 ±8.4) participated in the study, providing [11C]-(+)-PHNO scans at baseline and after an acute DA depletion challenge. Depletion was achieved via oral administration of α-MPT (64 mg/kg). The maximal inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase (and thus DA synthesis) with α-MPT has been observed to be ~80% (Engelman, Jequier, Udenfriend, & Sjoerdsma, 1968; Laruelle et al., 1997). Thus all α-MPT-PET studies underestimate their quantification of DA levels accordingly. Despite this underestimation, this method is still sensitive enough to elucidate differences in endogenous DA levels between healthy controls and persons with schizophrenia. While there are differences in the rate of α-MPT metabolism across individuals (Engelman et al., 1968), dosing regimens of α-MPT aim to achieve maximal tyrosine hydroxylase inhibition during PET scans. Notably, individual differences in plasma levels of α-MPT have not been found to be correlated with changes in BPND. Full details regarding the DA depletion and PET scanning protocols can be found in the parent study (Caravaggio et al., 2014). We only analyzed data from those regions of interest (ROIs) where [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND reliably increased after DA depletion. Thus, the substantia nigra (SN)/ventral tegmental area (VTA), hypothalamus, and ventral pallidum ROIs were excluded. The unique nature of these ROIs with regards to [11C]-(+)-PHNO, as well as potential explanations for their paradoxical binding, has been discussed in detail elsewhere (Caravaggio et al., 2014). Briefly, based on the results of animal studies combining the use of microdialysis and PET, it has been argued that the α-MPT-PET paradigm can only quantify DA levels at synaptic D2/3R, not extrasynaptic D2/3R (Breier et al., 1997; Kim & Han, 2009; Laruelle, 2000). Similarly to the retina (Hirasawa, Contini, & Raviola, 2015), there is no synaptic DA release into the SN (Bergquist & Nissbrandt, 2005), nor into the VTA (Adell & Artigas, 2004; Kalivas & Duffy, 1991; Omelchenko & Sesack, 2009). Rather, DA is stored and released extrasynaptically from the dendrites of the SN/VTA (Adell & Artigas, 2004; Cheramy, Leviel, & Glowinski, 1981; Geffen, Jessell, Cuello, & Iversen, 1976; Jaffe, Marty, Schulte, & Chow, 1998; Korf, Zieleman, M., & Westerink, 1976; Nieoullon, Cheramy, & Glowinski, 1977; Wassef, Berod, & Sotelo, 1981). Consistently, no significant change in [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND to extrasynaptic D3R in the SN/VTA was observed after DA depletion with α-MPT (Caravaggio et al., 2014). However, one study did observe a significant increase in D2/3R BPND in the SN/VTA after α-MPT using [18F]-fallypride (Riccardi et al., 2008). This was not confirmed in another study employing a larger sized sample (Cropley et al., 2008). Despite these discrepancies in the literature, the SN/VTA ROI for [11C]-(+)-PHNO was excluded from our current analysis due to our observation of no change in BPND to extrasynaptic D3R after α-MPT, consistent with findings from microdialysis-PET experiments. For the hypothalamus and ventral pallidum, baseline and post BPND’s could not be reliably calculated for all subjects. Despite following the ROI segmentation guidelines of Tziortzi and colleagues (Tziortzi et al., 2011), for some subjects we observed poor SRTM model fitting (associated with noise in the time-activity curve) and no washout of the signal. While it is unclear why in our hands this occurred, it is reassuring to note that our reported BPND values in those subjects for which it was possible are in accordance with previous reports (Tziortzi et al., 2011). Coupled with a lack of test-retest reliability data for these regions (Gallezot, Zheng, et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2013; Willeit et al., 2008), these ROIs were excluded from the current analysis. Finally, it has been demonstrated that the acute DA depletion induced by the α-MPT-PET paradigm is not enough to induce a significant up-regulation in the number of striatal D2/3R in rodents (Laruelle et al., 1997). This is assumed to also be true for humans. In turn, given this acute DA depletion and lack of change in receptor expression, it is also unlikely to alter the affinity of D2/3R for agonists (Todd, Carl, Harmon, O’malley, & Perlmutter, 1996).

2.2 | Estimates of endogenous DA levels at D2/3R

We examine three measures that estimate endogenous DA levels at baseline in the vicinity of the D2/3R. These are computed from the change in [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND induced by DA depletion with α-MPT in the following ways.

2.2.1 | The “α-MPT effect”

The term “α-MPT effect” has been used (Abi-Dargham et al., 2000) to denote the percent change in baseline radiotracer binding resulting from DA depletion: ΔBPND =−100*(Depletion BPND – Baseline BPND)/ Baseline BPND. The relationship of ΔBPND to endogenous DA at baseline is based on the occupancy model, in which endogenous DA competes with the binding of radiotracers like [11C]-(+)-PHNO for D2/3R at baseline (Laruelle, 2000; Laruelle et al., 1997; Verhoeff et al., 2001). It is assumed by this model that, (a) baseline D2/3R BPND is confounded by endogenous DA, such that higher concentration of DA results in lower D2/3R BPND, (b) D2/3R BPND under depletion more accurately reflects the true status of D2/3R, and, (c) the percent increase in D2/3R BPND after DA depletion, ΔBPND, is linearly proportional to the baseline DA concentration at D2/3R, provided the process of DA depletion does not change the number and affinity of the D2/3R. Thus, ΔBPND, under appropriate assumptions, is considered a quantitative index of baseline endogenous DA levels at D2/3R (Verhoeff et al., 2001).

2.2.2 | D2/3R occupancy by DA

The estimate of D2/3R occupancy by DA is calculated as a percent change in radiotracer binding induced by DA depletion, relative to the depletion BPND: %Occ = 100*(Depletion BPND – Baseline BPND)/ Depletion BPND. Since 100% DA depletion cannot be achieved with oral α-MPT, the true receptor occupancy by DA is underestimated in such paradigms. This metric has been used in some studies in lieu of calculating ΔBPND (Martinez et al., 2009).

2.2.3 | Free synaptic DA concentration

It has been suggested that the free synaptic DA concentration (FDA) (nM) can be estimated from α-MPT PET studies using the following formula: FDA = Ki(a − 1), where “a” is Depletion BPND/Baseline BPND, and Ki is the intrinsic affinity of DA to compete with the radiotracer (Abi-Dargham et al., 2000; Laruelle et al., 1997). The use of the above formula to calculate FDA requires several assumptions, which are to some extent violated in α-MPT studies. These include the assumptions of, (a) achieving 100% DA depletion with α-MPT and (b) competitive inhibition between DA and the radiotracer occurring at only one receptor site (Laruelle et al., 1997). Moreover, since Ki is unknown in vivo, an in vitro estimate must be used. Thus, the formula assumes similar Ki values in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, the necessary Ki values are often not available from human postmortem tissue. Notably, the two AMPT [123I]-IBZM studies, which attempted to estimate striatal FDA using this formula did so using Ki values from rodent striata. Moreover, Ki in vitro differs based on the presence or absence of NaCl, and it is unclear which values are most appropriately used (Laruelle et al., 1997). Despite the limitations inherent to making assumptions about in vivo conditions from in vitro data, the above formula is currently the only one available in the literature for calculating FDA from α-MPT PET data. Nevertheless, important and consistent observations have been made using this calculation of FDA in healthy persons and persons with schizophrenia (Abi-Dargham et al., 2000; Laruelle, 2012; Laruelle et al., 1997). Ultimately, the usefulness of this quantification will be evidenced by its ability to produce consistent findings with the larger body of literature, and make accurate predictions for future investigations.

2.3 | Validation by estimating the kd for DA at D2/3R in vivo

In theory, the relationship between the fraction of radiotracer bound to receptors does not increase continuously with decreasing competition from endogenous DA. Rather, it approaches an asymptotic limit, which has been simulated and described mathematically (Friedman et al., 1984). For further details on the mathematical equations describing the competition of two ligands for one receptor site, please see the work of Friedman et al. (1984). Assuming that the concentration of free synaptic DA remains constant during a respective PET scan, and then the relationship between free synaptic DA and the amount of DA bound to receptors should also approach an asymptotic limit, and be nonlinear. The relationship between the free synaptic DA concentration (FDA) and receptor occupancy (%Occ) can be viewed as analogous to an in vitro saturation binding plot. These plots (known as a rectangular hyperbola, binding isotherm, or saturation binding curves) describe the binding of a ligand to a receptor as a function of increasing ligand concentration at equilibrium. The concentration of the ligand is plotted on the x-axis and the amount of specific-binding to receptors is plotted on the y-axis, with the half-maximal point of the curve signifying the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd). Kd here signifies the concentration of ligand that occupies half the binding sites at equilibrium. This can be described using the following equation: ; where X denotes the concentration of ligand and Y denotes specific binding. For a hypothetical saturation binding curve, please see Figure 1. Notably, Y is initially zero, and increases until it reaches the value of Bmax. Despite the PET experiments not being conducted at equilibrium, by plotting the natural variation in the free synaptic DA concentration (x-axis) versus receptor occupancy (y-axis) across people, this may provide an estimate of Kd for DA at D2R and D3R in vivo in humans. These estimates can then be compared to in vitro values reported in the literature. Notably, in vitro the fraction of a ligand bound to receptors does not increase linearly with increasing concentrations of a ligand, but rather reaches an asymptotic limit (Friedman et al., 1984).

FIGURE 1.

A hypothetical plot of a typical saturation binding curve used to calculate the dissociation constant (Kd) of a ligand for its target

3 | RESULTS

3.1 | Relationship of baseline BPND with endogenous DA levels

The relationships between baseline BPND and three measures of baseline endogenous DA levels (ΔBPND, %Occ, and FDA) are presented in Table 1. R2-values in this table signify the proportion of the variance in baseline [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND which can be accounted for by endogenous DA estimated by these three quantities respectively. Notably, persons with lower [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND to D2/3R at baseline demonstrated greater levels of endogenous DA occupying these receptors, and vice-versa, Thus, lower baseline values of [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND reflect greater stimulation by endogenous DA, and vice-versa Plasma levels of α-MPT (27 h) were not significantly correlated with endogenous DA levels or receptor occupancy as measured with [11C]-(+)-PHNO (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Correlations between baseline [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND and three measures of endogenous DA levels in each region of interest

| Region of Interest | ΔBPND (α-MPT effect)

|

%Occ (receptor occupancy by endogenous DA)

|

FDA (free synaptic DA concentration)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r-value | r2 | p values | r-value | r2 | p values | r-value | r2 | p values | |

| Caudate | −0.77 | 0.59 | 0.01b | −0.75 | 0.56 | 0.01b | −0.78 | 0.61 | 0.01b |

|

| |||||||||

| Putamen | −0.77 | 0.59 | 0.009c | −0.75 | 0.56 | 0.01b | −0.77 | 0.59 | 0.009c |

|

| |||||||||

| Ventral Striatum | −0.65 | 0.42 | 0.04b | −0.70 | 0.49 | 0.02b | −0.65 | 0.42 | 0.04b |

|

| |||||||||

| Globus Pallidus | −0.33 | 0.11 | 0.35 | −0.35 | 0.12 | 0.32 | −0.34 | 0.12 | 0.34 |

|

| |||||||||

| Covariate: Plasma AMPT (27 h) | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Caudate | −0.67 | 0.45 | 0.05a | −0.65 | 0.42 | 0.06 | −0.67 | 0.45 | 0.05a |

|

| |||||||||

| Putamen | −0.68 | 0.46 | 0.04b | −0.64 | 0.41 | 0.06 | −0.69 | 0.48 | 0.04b |

|

| |||||||||

| Ventral Striatum | −0.81 | 0.66 | 0.008c | −0.85 | 0.72 | 0.004c | −0.81 | 0.66 | 0.009c |

|

| |||||||||

| Globus Pallidus | −0.32 | 0.10 | 0.40 | −0.33 | 0.11 | 0.39 | −0.33 | 0.11 | 0.39 |

Denotes trend level significance (two-tailed).

Denotes significance at p <0.05, two-tailed.

Denotes significance at p <0.01, two-tailed.

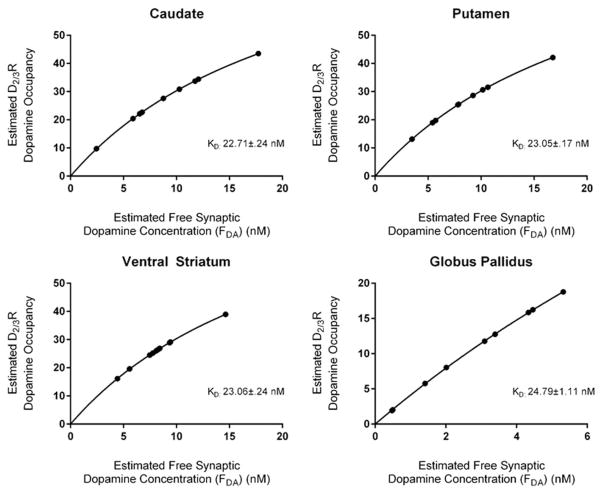

3.2 | Kd for DA at D2/3R

Our estimate of FDA, the free synaptic DA concentration in each ROI, used only those subjects whose BPND in a given ROI increased after DA depletion. Nine subjects provided data for the caudate, putamen, and GP ROIs, and 10 subjects provided data for the VS. To date, no study has published Ki values for DA to inhibit [3H]-(+)PHNO binding in human striata. In canine striata, two Ki values have been reported: 4.2 (−NaCl) and 23 (+NaCl; Seeman et al., 1993). Using a Ki of 23, the FDA was estimated to be the following: VS 8.34 ± 2.71 nM, Caudate 9.13 ±4.45 nM, Putamen 8.57 ±3.87 nM, GP 2.78 ±1.77 nM. Using these data, we used FDA to estimate the Kd for DA at D2/3R in each ROI, using the saturation binding curve equation (see Figure 2). The calculated Kd values ranged from 22 to 24 nM.

FIGURE 2.

The in vivo dissociation constant (Kd) for DA at D2/3R in each region of interest

4| DISCUSSION

The PET α-MPT paradigm is currently the optimal method for quantifying endogenous DA levels in the living human brain—providing the most direct evidence for dopaminergic abnormalities in several neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and drug addiction (Abi-Dargham et al., 2000; Kegeles et al., 2010; Martinez et al., 2009). Here, we show that these data can also provide valuable information regarding the interpretation of dopaminergic radiotracer binding during baseline conditions. Specifically, α-MPT PET data can inform to what extent a radiotracer for D2/3R is sensitive to endogenous DA at baseline. Re-analyzing previously published data (Caravaggio et al., 2014), we report for [11C]-(+)-PHNO the proportion of the variance in baseline BPND, which can be accounted for by endogenous DA. This ranged from ~40 to 60% across striatal ROIs. Indeed as previously suggested (Caravaggio et al., 2014, 2015a; Laruelle, 2012; Shotbolt et al., 2012), [11C]-(+)-PHNO is highly sensitive to changes in endogenous DA levels, and individual differences at baseline. This sensitivity is likely much greater than that of other commonly used radiotracers like [11C]-raclopride, and may explain some of the differential findings observed between agonist and antagonist radiotracers, even within the same persons (Caravaggio et al., 2015b; Narendran et al., 2011). Using this dataset, we also estimated the free synaptic DA concentration (nM), and in turn the Kd value for DA at D2/3R, in the living human brain. Several in vitro studies suggest that the Kd of [3H]-DA for striatal D2/3R is about 20 nM (Burt, Creese, & Snyder, 1976; Creese, Burt, & Snyder, 1976; Durdagi, Salmas, Stein, Yurtsever, & Seeman, 2015; Komiskey, Bossart, Miller, & Patil, 1978). For example, in rodent striata it has been reported that DA has a Kd of 21.69 nM for the high affinity state and 5.64 nM for the low affinity state (Komiskey et al., 1978). These values are in line with those Kd values estimated here (22–24 nM), adding more proof of concept to the measurement of endogenous DA in vivo using PET- α-MPT.

The increased sensitivity of [11C]-(+)-PHNO to changes in endogenous DA confers several advantages. For instance, it can quantify small changes in DA release which may not be captured by antagonists such as [11C]-raclopride. For example, in non-human primates the same dose of nicotine (0.1 mg/kg) could significantly reduce the BPND of [11C]-(+)-PHNO, but not [11C]-raclopride (Gallezot, Kloczynski, et al., 2014). Thus, [11C]-(+)-PHNO could reliably quantify the small increase in DA release induced by nicotine administration, while [11C]-raclopride could not. Given that PET studies are usually of high cost and thus employ small sample sizes, use of [11C]-(+)-PHNO lends the practical advantage of being able to detect smaller effect sized changes in DA, thus conferring greater statistical power in smaller samples (Ko et al., 2011). Thus, use of the α-MPT-PET paradigm in conjunction with [11C]-(+)-PHNO may allow for a better detection of abnormal DA levels in neuropsychiatric diseases. For example, while reduced endogenous mesolimbic DA is often cited as a pathophysiological marker of depression (Salamone et al., 2016; Treadway and Zald, 2011), no differences in baseline [11C]-raclopride BPND have been observed (Hirvonen et al., 2008; Meyer et al., 2006; Montgomery et al., 2007). Moreover, the α-MPT-PET paradigm has never been employed in persons with depression using a radiotracer for D2/3R (Bremner et al., 2003). Thus, the use of [11C]-(+)-PHNO may elucidate the potential abnormalities in endogenous mesolimbic DA in persons with depression, which [11C]-raclopride could not detect; at baseline and after a DA depletion challenge. This would ultimately vindicate the DA hypothesis of depression, which heretofore has yet to be directly confirmed by in vivo brain imaging.

There are several potential limitations to the current investigation. First, our sample size was relatively small, though large enough to detect a significant change in [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND after DA depletion. While we employed a typical sample size for an α-MPT–PET study, future studies aimed at quantifying endogenous DA at D2/3R using α-MPT and [11C]-(+)-PHNO will benefit from employing larger sample sizes. Second, it is possible that individual differences in DA synthesis capacity and/or DA clearance can affect the estimate of endogenous DA using the α-MPT paradigm. In theory, every individual is given the maximum amount of α-MPT exposure which results in 80% tyrosine hydroxylase inhibition and thus DA synthesis. However, in practice this may not always be the case for all subjects. At least for the current investigation, we employed all healthy subjects of relatively young age. Thus, we expect individual differences in DA synthesis and clearance to me minimal. Notably, this is a potential limitation shared by all α-MPT-PET studies.

Though focused on [11C]-(+)-PHNO, this report provides a framework for analyses of α-MPT PET studies with other D2/3R radioligands such as [11C]-raclopride, [18F]-fallypride, and [11C]-NPA to evaluate endogenous DA levels at baseline. With this approach, the impact of endogenous DA levels on single baseline-only PET studies with these radioligands can be assessed.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, Zea-Ponce Y, Gil R, Kegeles LS, … Laruelle M. Increased baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:8104–8109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adell A, Artigas F. The somatodendritic release of dopamine in the ventral tegmental area and its regulation by afferent transmitter systems. Neuroscience and Behavioral Reviews. 2004;28:415–431. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist F, Nissbrandt H. Dendritic Neurotransmitter Release. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2005. Dopamine release in substantia nigra: elease mechanisms and physiological function in motor control; pp. 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bloemen OJ, de Koning MB, Gleich T, Meijer J, de Haan L, Linszen DH, … van Amelsvoort TA. Striatal dopamine D2/3 receptor binding following dopamine depletion in subjects at ultra high risk for psychosis. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;23:126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier A, Su TP, Saunders R, Carson RE, Kolachana BS, de Bartolomeis A, … Pickar D. Schizophrenia is associated with elevated amphetamine-induced synaptic dopamine concentrations: evidence from a novel positron emission tomography method. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:2569–2574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Ng CK, Vermetten E, Nazeer A, Oren DA, … Charney DS. Regional brain metabolic correlates of alpha-methylparatyrosine-induced depressive symptoms: implications for the neural circuitry of depression. JAMA. 2003;289:3125–3134. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt DR, Creese I, Snyder SH. Properties of [3H] haloperidol and [3H] dopamine binding associated with dopamine receptors in calf brain membranes. Molecular Pharmacology. 1976;12:800–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caravaggio F, Borlido C, Wilson A, Graff-Guerrero A. Examining endogenous dopamine in treated schizophrenia using [(1) (1)C]-(+)-PHNO positron emission tomography: A pilot study. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2015a;449:60–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caravaggio F, Nakajima S, Borlido C, Remington G, Gerretsen P, Wilson A, … Graff-Guerrero A. Estimating endogenous dopamine levels at D2 and D3 receptors in humans using the agonist radiotracer [(11)C]-(+)-PHNO. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:2769–2776. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caravaggio F, Raitsin S, Gerretsen P, Nakajima S, Wilson A, Graff-Guerrero A. Ventral striatum binding of a dopamine D2/3 receptor agonist but not antagonist predicts normal body mass index. Biological Psychiatry. 2015b;77:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheramy A, Leviel V, Glowinski J. Dendritic release of dopamine in the substantia nigra. Nature. 1981;289:537–542. doi: 10.1038/289537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comar D, Zarifian E, Verhas M, Soussaline F, Maziere M, Berger G, … Deniker P. Brain distribution and kinetics of 11C-chlorpromazine in schizophrenics: Positron emission tomography studies. Psychiatry Research. 1979;1:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(79)90024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creese I, Burt DR, Snyder SH. Dopamine receptor binding: Differentiation of agonist and antagonist states with 3H-dopamine and 3H-haloperidol. Life Sciences. 1975;17:993–1001. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(75)90454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creese I, Burt DR, Snyder SH. Dopamine receptor binding predicts clinical and pharmacological potencies of antischizophrenic drugs. Science. 1976;192:481–483. doi: 10.1126/science.3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cropley VL, Innis RB, Nathan PJ, Brown AK, Sangare JL, Lerner A, … Fujita M. Small effect of dopamine release and no effect of dopamine depletion on [18F]fallypride binding in healthy humans. Synapse (New York, NY) 2008;62:399–408. doi: 10.1002/syn.20506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koning MB, Bloemen OJ, Van Duin ED, Booij J, Abel KM, De Haan L, … Van Amelsvoort TA. Pre-pulse inhibition and striatal dopamine in subjects at an ultra-high risk for psychosis. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 2014;28:553–560. doi: 10.1177/0269881113519507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durdagi S, Salmas RE, Stein M, Yurtsever M, Seeman P. Binding interactions of dopamine and apomorphine in D2High and D2Low states of human dopamine D2 receptor using computational and experimental techniques. ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 2015;7:185–195. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman K, Jequier E, Udenfriend S, Sjoerdsma A. Metabolism of alpha-methyltyrosine in man: Relationship to its potency as an inhibitor of catecholamine biosynthesis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1968;47:568–576. doi: 10.1172/JCI105753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnema SJ, Seneca N, Farde L, Shchukin E, Sovago J, Gulyas B, … Halldin C. A preliminary PET evaluation of the new dopamine D2 receptor agonist [11C]MNPA in cynomolgus monkey. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2005;32:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman AM, DeJesus OT, Revenaugh J, Dinerstein RJ. Measurements in vivo of parameters of the dopamine system. Annals of Neurology. 1984;15(Suppl):S66–S76. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallezot JD, Kloczynski T, Weinzimmer D, Labaree D, Zheng MQ, Lim K, … Cosgrove KP. Imaging nicotine- and amphetamine-induced dopamine release in rhesus monkeys with [(11)C]PHNO vs [(11) C]raclopride PET. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014a;39:866–874. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallezot JD, Zheng MQ, Lim K, Lin SF, Labaree D, Matuskey D, … Malison RT. Parametric imaging and Test-retest variability of 11C-(+)-PHNO binding to D2/D3 dopamine receptors in humans on the High-resolution research tomograph PET scanner. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2014b;55:960–966. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.132928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geffen LB, Jessell TM, Cuello AC, Iversen LL. Release of dopamine from dendrites in rat substantia nigra. Nature. 1976;260:258–260. doi: 10.1038/260258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SR, Watanabe M, Di Paolo T, Falardeau P, Labrie F, Seeman P. The functional state of the dopamine receptor in the anterior pituitary is in the high affinity form. Endocrinology. 1985;117:690–697. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-2-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn RN, Slifstein M, Searle GE, Price JC. Quantitative imaging of protein targets in the human brain with PET. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2015;60:R363–R411. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/22/R363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin MW, Leff SE, Creese I. Interactions of agonists with D-2 dopamine receptors: Evidence for a single receptor population existing in multiple agonist affinity-states in rat striatal membranes. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1984;33:877–887. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa H, Contini M, Raviola E. Extrasynaptic release of GABA and dopamine by retinal dopaminergic neurons. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 2015;370:20140186. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen J, Karlsson H, Kajander J, Markkula J, Rasi-Hakala H, Nagren K, et al. Striatal dopamine D2 receptors in medication-naive patients with major depressive disorder as assessed with [11C] raclopride PET. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:581–590. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Kodaka F, Takahashi H, Takano H, Arakawa R, Shimada H, Suhara T. Relation between presynaptic and postsynaptic dopaminergic functions measured by positron emission tomography: implication of dopaminergic tone. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:7886–7890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6024-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe EH, Marty A, Schulte A, Chow RH. Extrasynaptic vesicular transmitter release from the somata of substantia nigra neurons in rat midbrain slices. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:3548–3553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03548.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Duffy P. A comparison of axonal and somato-dendritic dopamine release using in vivo dialysis. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1991;56:961–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles LS, Abi-Dargham A, Frankle WG, Gil R, Cooper TB, Slifstein M, … Laruelle M. Increased synaptic dopamine function in associative regions of the striatum in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:231–239. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles LS, Martinez D, Slifstein M, Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A. Baseline [11C]raclopride binding potential is inversely related to D2/3 receptor stimulation by endogenous dopamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:S112–S290. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SE, Han SM. Nicotine- and methamphetamine-induced dopamine release evaluated with in-vivo binding of radiolabelled raclopride to dopamine D2 receptors: Comparison with in-vivo microdialysis data. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;12:833–841. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JH, Reilhac A, Ray N, Rusjan P, Bloomfield P, Pellecchia G, et al. Analysis of variance in neuroreceptor ligand imaging studies. PloS One. 2011;6:e23298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler C, Hall H, Ogren SO, Gawell L. Specific in vitro and in vivo binding of 3H-raclopride. A potent substituted benzamide drug with high affinity for dopamine D-2 receptors in the rat brain. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1985;34:2251–2259. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiskey HL, Bossart JF, Miller DD, Patil PN. Conformation of dopamine at the dopamine receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1978;75:2641–2643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf J, Zieleman M, Westerink BHC. Dopamine release in substantia nigra? Nature. 1976;260:257–258. doi: 10.1038/260257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M. Imaging synaptic neurotransmission with in vivo binding competition techniques: a critical review. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2000;20:423–451. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M. Measuring dopamine synaptic transmission with molecular imaging and pharmacological challenges: The state of the art. In: Gründer G, editor. Molecular imaging in the clinical neurosciences. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2012. pp. 163–203. [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, D’souza CD, Baldwin RM, Abi-Dargham A, Kanes SJ, Fingado CL, … Innis RB. Imaging D2 receptor occupancy by endogenous dopamine in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;17:162–174. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DE, Gallezot JD, Zheng MQ, Lim K, Ding YS, Huang Y, … Cosgrove KP. Test-retest reproducibility of [11C]-(+)-propyl-hexahydro-naphtho-oxazin positron emission tomography using the bolus plus constant infusion paradigm. Molecular Imaging. 2013;12:77–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D, Greene K, Broft A, Kumar D, Liu F, Narendran R, et al. Lower level of endogenous dopamine in patients with cocaine dependence: Findings from PET imaging of D(2)/D(3) receptors following acute dopamine depletion. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1170–1177. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald WM, Sibley DR, Kilpatrick BF, Caron MG. Dopaminergic inhibition of adenylate cyclase correlates with high affinity agonist binding to anterior pituitary D2 dopamine receptors. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1984;36:201–209. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(84)90037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JH, McNeely HE, Sagrati S, Boovariwala A, Martin K, Verhoeff NP, et al. Elevated putamen D(2) receptor binding potential in major depression with motor retardation: An [11C] raclopride positron emission tomography study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1594–1602. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery AJ, Stokes P, Kitamura Y, Grasby PM. Extrastriatal D2 and striatal D2 receptors in depressive illness: pilot PET studies using [11C]FLB 457 and [11C]raclopride. Journal of Effective Disorders. 2007;101:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran R, Hwang DR, Slifstein M, Talbot PS, Erritzoe D, Huang Y, et al. In vivo vulnerability to competition by endogenous dopamine: comparison of the D2 receptor agonist radio-tracer (-)-N-[11C]propyl-norapomorphine ([11C]NPA) with the D2 receptor antagonist radiotracer [11C]-raclopride. Synapse (New York) 2004;52:188–208. doi: 10.1002/syn.20013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran R, Martinez D, Mason NS, Lopresti BJ, Himes ML, Chen C-M, et al. Imaging of dopamine D2/3 agonist binding in cocaine dependence: a [11C]NPA positron emission tomography study. Synapse (New York) 2011;65:1344–1349. doi: 10.1002/syn.20970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran R, Mason NS, Laymon CM, Lopresti BJ, Velasquez ND, May MA, et al. A comparative evaluation of the dopamine D(2/3) agonist radiotracer [11C](-)-N-propyl-norapomorphine and antagonist [11C]raclopride to measure amphetamine-induced dopamine release in the human striatum. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2010;333:533–539. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.163501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieoullon A, Cheramy A, Glowinski J. Release of dopamine in vivo from cat substantia nigra. Nature. 1977;266:375–377. doi: 10.1038/266375a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omelchenko N, Sesack SR. Ultrastructural analysis of local collaterals of rat ventral tegmental area neurons: GABA phenotype and synapses onto dopamine and GABA cells. Synapse (New York) 2009;63:895–906. doi: 10.1002/syn.20668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi P, Baldwin R, Salomon R, Anderson S, Ansari MS, Li R, et al. Estimation of baseline dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in striatum and extrastriatal regions in humans with positron emission tomography with [18F] fallypride. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:241–244. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richfield EK, Young AB, Penney JB. Properties of D2 dopamine receptor autoradiography: high percentage of high-affinity agonist sites and increased nucleotide sensitivity in tissue sections. Brain Research. 1986;383:121–128. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD, Correa M, Yohn S, Lopez Cruz L, San Miguel N, Alatorre L. The pharmacology of effort-related choice behavior: dopamine, depression, and individual differences. Behavioural Processes. 2016;127:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P. Brain dopamine receptors in schizophrenia: PET problems. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:598–600. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800300096017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P. Elevated D2 in schizophrenia: role of endogenous dopamine and cerebellum. Commentary on “the current status of PET scanning with respect to schizophrenia”. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1992;7:55–57. discussion 73–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P. Historical Overview: Introduction to the Dopamine Receptors. In: Neve KA, editor. The opamine Receptors. New York City, New York: Humana Press; 2010. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P. All roads to schizophrenia lead to dopamine super-sensitivity and elevated dopamine D2High receptors. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2011;17:118–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Guan HC, Niznik HB. Endogenous dopamine lowers the dopamine D2 receptor density as measured by [3H] raclopride: implications for positron emission tomography of the human brain. Synapse (New York) 1989;3:96–97. doi: 10.1002/syn.890030113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Niznik HB, Guan HC. Elevation of dopamine D2 receptors in schizophrenia is underestimated by radioactive raclopride. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:1170–1172. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810240090014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Ulpian C, Larsen RD, Anderson PS. Dopamine receptors labelled by PHNO. Synapse (New York) 1993;14:254–262. doi: 10.1002/syn.890140403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seneca N, Finnema SJ, Farde L, Gulyas B, Wikstrom HV, Halldin C, Innis RB. Effect of amphetamine on dopamine D2 receptor binding in nonhuman primate brain: A comparison of the agonist radioligand [11C]MNPA and antagonist [11C]raclopride. Synapse (New York) 2006;59:260–269. doi: 10.1002/syn.20238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shotbolt P, Tziortzi AC, Searle GE, Colasanti A, van der Aart J, Abanades S, et al. Within-subject comparison of [(11)C]-(+)-PHNO and [(11)C]raclopride sensitivity to acute amphetamine challenge in healthy humans. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2012;32:127–136. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley DR, D Lean A, Creese I. Anterior pituitary dopamine receptors. Demonstration of interconvertible high and low affinity states of the D-2 dopamine receptor. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1982a;257:6351–6361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley DR, De Lean A, Creese I. Anterior pituitary dopamine receptors. Demonstration of interconvertible high and low affinity states of the D-2 dopamine receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1982b;257:6351–6361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starke K, Reimann W, Zumstein A, Hertting G. Effect of dopamine receptor agonists and antagonists on release of dopamine in the rabbit caudate nucleus in vitro. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 1978;305:27–36. doi: 10.1007/BF00497003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd RD, Carl J, Harmon S, O’malley KL, Perlmutter JS. Dynamic changes in striatal dopamine D2 and D3 receptor protein and mRNA in response to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) denervation in baboons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:7776–7782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07776.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadway MT, Zald DH. Reconsidering anhedonia in depression: lessons from translational neuroscience. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35:537–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tziortzi AC, Searle GE, Tzimopoulou S, Salinas C, Beaver JD, Jenkinson M, et al. Imaging dopamine receptors in humans with [11C]-(+)-PHNO: dissection of D3 signal and anatomy. Neuroimage. 2011;54:264–277. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeff NP, Christensen BK, Hussey D, Lee M, Papatheodorou G, Kopala L, … Kapur S. Effects of catecholamine depletion on D2 receptor binding, mood, and attentiveness in humans: A replication study. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2003;74:425–432. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeff NP, Hussey D, Lee M, Tauscher J, Papatheodorou G, Wilson AA, … Kapur S. Dopamine depletion results in increased neostriatal D(2), but not D(1), receptor binding in humans. Molecular Psychiatry. 2002;7:233, 322–238. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeff NP, Kapur S, Hussey D, Lee M, Christensen B, Psych C, … Zipursky RB. A simple method to measure baseline occupancy of neostriatal dopamine D2 receptors by dopamine in vivo in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:213–223. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner HN, Jr, Burns HD, Dannals RF, Wong DF, Langstrom B, Duelfer T, … Kuhar MJ. Imaging dopamine receptors in the human brain by positron tomography. Science. 1983;221:1264–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.6604315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassef M, Berod A, Sotelo C. Dopaminergic dendrites in the pars reticulata of the rat substantia nigra and their striatal input. Combined immunocytochemical localization of tyrosine hydroxylase and anterograde degeneration. Neuroscience. 1981;6:2125–2139. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(81)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willeit M, Ginovart N, Graff A, Rusjan P, Vitcu I, Houle S, … Kapur S. First human evidence of d-amphetamine induced displacement of a D2/3 agonist radioligand: A [11C]-(+)-PHNO positron emission tomography study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:279–289. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willeit M, Ginovart N, Kapur S, Houle S, Hussey D, Seeman P, Wilson AA. High-affinity states of human brain dopamine D2/3 receptors imaged by the agonist [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]