Abstract

The incidence of prostate cancer is much lower in Asian than in Western populations. Lifestyle and dietary habits may play a major role in the etiology of this cancer. Given the possibility that risk factors for prostate cancer differ by disease aggressiveness, and the fact that 5-year relative survival rate of localized prostate cancer is 100%, identifying preventive factors against advanced prostate cancer is an important goal.

Using data from the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study, the author elucidates various lifestyle risk factors for prostate cancer among Japanese men. The results show that abstinence from alcohol and tobacco might be important factors in the prevention of advanced prostate cancer. Moreover, the isoflavones and green tea intake in the typical Japanese diet may decrease the risk of localized and advanced prostate cancers, respectively.

1. Introduction

Although the incidence of prostate cancer in Japan is rapidly increasing, it is still much lower than in Western populations.1 However, Japanese migrants to the United States and Brazil have increased incidence,2,3 and the incidence of latent or clinically insignificant prostate cancer between Asian countries and the United States is similar in autopsy studies.4,5 Therefore, it has been suggested that environmental factors may play an important role in the progression of prostate cancer.

In addition, although prostate cancer is clinically diagnosed as local (i.e., confined to the prostate) or advanced (i.e., distantly spread), studies of the association of various suspected risk factors with aggressive prostate cancer have been conflicting.6 Risk factors for localized prostate cancer might differ from those for advanced prostate cancer. Moreover, the 5-year relative survival rate of patients with localized prostate cancer is 100%,7 so it is important to focus preventive efforts on advanced prostate cancer.

The Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective (JPHC) Study is a large-scale population-based prospective study that has been conducted since 1990 in 11 public health center-based areas across Japan. The subjects were 140,420 residents aged 40–69 years. Questionnaires, blood samples, and health screening data were collected. We have followed this cohort for over 20 years, and a sufficient number of incident cancers has accumulated, although the number of prostate cancer cases is still lower than would be expected in Western countries.

Here, to elucidate the influence of risk factors for prostate cancer — namely tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, body mass index (BMI), and diet — on prostate cancer according to stage, we conducted cohort analyses using data from the JPHC Study.

2. JPHC study

The JPHC Prospective Study started in 1990 for Cohort I and in 1993 for Cohort II. The study design has been described in detail elsewhere.8 Cohort I consisted of five Public Health Center (PHC) areas, involving the following PHC centers (Prefecture): Ninohe (Iwate), Yokote (Akita), Saku (Nagano), Chubu (Okinawa), and Katsushika (Tokyo); while Cohort II consisted of six PHC areas, with the following PHC centers (Prefecture): Mito (Ibaraki), Nagaoka (Niigata), Chuo-higashi (Kochi), Kamigoto (Nagasaki), Miyako (Okinawa), and Suita (Osaka). The study population was defined as all residents aged 40–59 years in Cohort I and 40–69 years in Cohort II at the start of the respective baseline survey. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Center of Japan. For the analysis in this review, the Katsushika PHC area was excluded because cancer incidence was not available.

The questionnaire was distributed primarily by hand from 1990 to 1994 (baseline survey). Approximately 113,000 people returned the questionnaire, and 48,000 provided blood samples or health checkup data, with most providing both. To update information on lifestyle and health conditions, a 5-year follow-up questionnaire survey was conducted from 1995 to 1999. In the 5-year survey, we asked subjects to respond to a comprehensive food frequency questionnaire (147 food item and beverages), so the 5-year questionnaire was used as the starting point for the association between diet and prostate cancer. The response rate was around 80%. Subjects with a history of prostate cancer were excluded from these analyses.

Information on the cause of death for deceased subjects was obtained from death certificates, which were provided by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and were used with permission. Mortality data was classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision. Resident registration and death registration are required by law in Japan, and the registries are believed to be complete. We have followed subjects from the starting point until the end of follow-up in each analysis. Changes in residence status, including deaths, were identified annually through the residential registry in each area. The proportion of subjects lost to follow-up was less than 1%.

We identified cancer occurrence using active patient notification from major local hospitals in the study area and data linkage with population-based cancer registries. Death certificate information was used as a supplement. Cases were coded using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition. In our study, the proportion of case patients with prostate cancer ascertained by death certificate only (DCO) was less than 5%.

Hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to describe the relative risk of the incidence of prostate cancer. The Cox proportional hazards model was used for this analysis, after controlling for potential confounding factors.

3. Lifestyle risk factors for prostate cancer: smoking and alcohol consumption

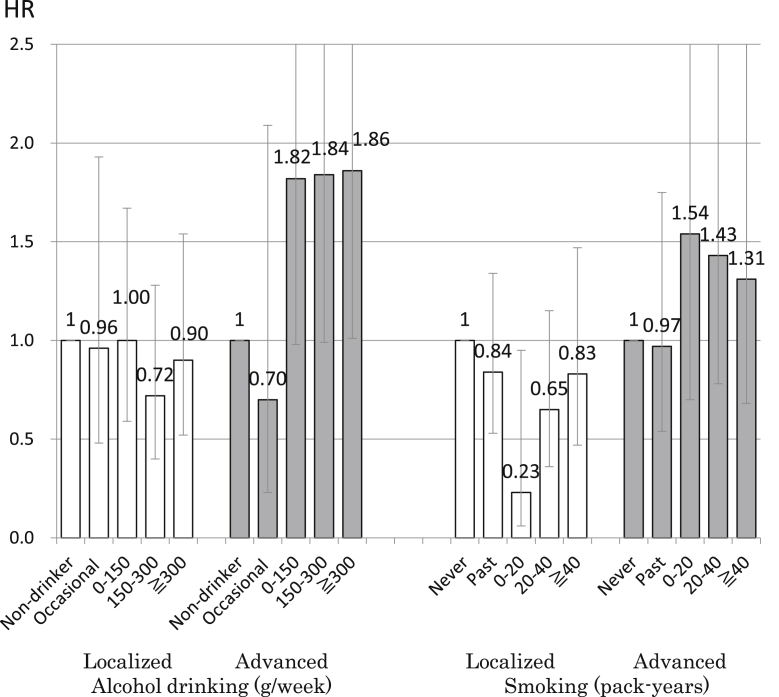

The associations of smoking and alcohol consumption with prostate cancer are shown in Fig. 1.9 Although alcohol drinking and smoking have not been established as risk factors for prostate cancer, they are important risk factors for other types of cancer. The report by the World Cancer Research Fund International's Continuous Update Project concluded that the data were too limited to determine an association between alcohol consumption and prostate cancer.10 Regarding smoking, the International Agency for Research on Cancer does not consider prostate cancer to be related to tobacco use.11 However, the United States Surgeon General reported that the evidence is suggestive of a higher risk of death from prostate cancer in smokers than in nonsmokers.12 In addition, alcohol drinkers and smokers might be less likely to receive screening, which might mask a positive association. We investigated the association of alcohol drinking and smoking with prostate cancer according to stage, as well as with prostate cancer detected by subjective symptoms, in a large prospective study of Japanese men. We evaluated 48,218 men aged 40–69 years who completed a questionnaire at baseline in 1990–1994 and who were followed until the end of 2010. During 16 years of follow-up, 913 men were newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, of whom 248 had advanced cases, 635 had localized cases, and 30 were of an undetermined stage. To exclude the influence of screening, we analyzed the association of prostate cancer with alcohol consumption in subjects whose cancer was detected by subjective symptoms (232 cases of prostate cancer, of which 103 were advanced cases and 121 were organ-localized). Results showed a positive association of alcohol consumption with prostate cancer in subjects with advanced disease: compared to non-drinkers, increased risks were observed for those who consumed 0–149 g/week (HR 1.82; 95% CI, 0.98–3.38), 150–299 g/week (HR 1.84; 95% CI, 0.99–3.42), and ≧300 g/week (HR 1.86; 95% CI, 1.01–3.44) (p for trend = 0.02). Smoking tended to be associated with an increased risk of advanced prostate cancer: compared to never smokers, nonsignificantly increased risks were observed for 0–19 pack-years (HR 1.54; 95% CI, 0.70–3.43), 20–39 pack-years (HR 1.43; 95% CI, 0.78–2.60), and ≥40 pack-years (HR 1.31; 95% CI, 0.68–2.53) (p for trend = 0.16). In conclusion, abstinence from alcohol and tobacco might be important factors in the prevention of advanced prostate cancer.

Fig. 1. The association between alcohol drinking, smoking, and prostate cancer according to stage in Japanese men.9 The error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. HR, hazard ratio.

4. Typical Japanese diet

The World Cancer Research Fund International's Continuous Update Project reported that the evidence of an association of prostate cancer with higher consumption of dairy products, diets high in calcium, low plasma alpha-tocopherol concentration, and low plasma selenium concentration is limited,10 and there are not many epidemiological studies on prostate cancer in Asia. To investigate the association of the Japanese traditional diet with prostate cancer in the Japanese population is informative, given the low incidence of prostate cancer compared with Western countries.

5. Isoflavones and soy foods

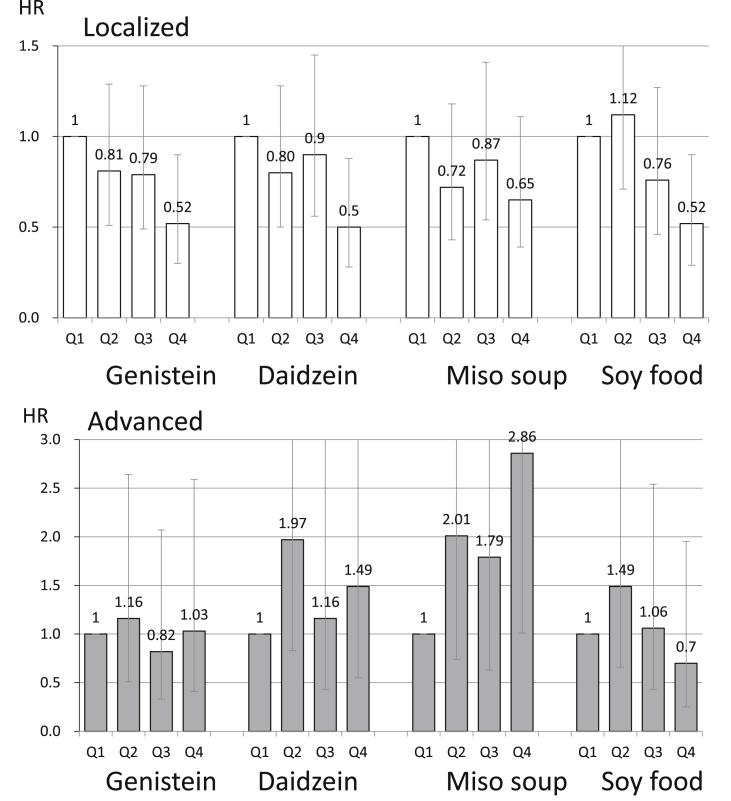

The associations of the consumption of isoflavones and soy foods with prostate cancer are shown in Fig. 2.13,14 The World Cancer Research Fund International's Continuous Update Project concluded that limited data were suggestive of an association between soy food intake and prostate cancer.10 Although isoflavones have been suggested to have a preventive effect against prostate cancer in animal experiments, the results of epidemiological studies have been inconsistent. We conducted a population-based prospective study in 43,509 Japanese men aged 45–74 years who responded to a validated food frequency questionnaire. During follow-up from 1995 through 2004, 307 men were newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, of whom 74 had advanced cases, 218 were localized cases, and 15 were of an undetermined stage. Intakes of genistein, daidzein, miso soup, and soy food decreased the risk of localized prostate cancer. These results were strengthened when analysis was confined to men aged >60 years; higher intake of isoflavones and soy food were inversely associated with the risk of localized cancer in a dose-dependent manner, with HRs for men in the highest compared with the lowest quartile of genistein, daidzein, and soy food consumption of 0.52 (95% CI, 0.30–0.90), 0.50 (95% CI, 0.28–0.88), and 0.52 (95% CI, 0.29–0.90), respectively. In contrast, positive associations were seen between intake of isoflavones and incidence of advanced prostate cancer. In conclusion, we found that isoflavone intake was associated with a decreased risk of localized prostate cancer.

Fig. 2. The association between isoflavones, soy foods, and prostate cancer according to stage in Japanese men.13 The error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. HR, hazard ratio; Q, quartile.

We also conducted a nested case-control study within the JPHC Study to evaluate the bioavailability of isoflavones and the effects of equol, a metabolite of daidzein produced by intestinal bacteria that is known to have stronger estrogenic activity than daidzein. A total of 14,203 men aged 40–69 years who had returned the baseline questionnaire and provided blood samples were followed from 1990 to 2005. During a mean 12.8 years of follow-up, 201 newly diagnosed prostate cancers were identified. Two matched controls for each case were selected from the cohort. Conditional logistic regression modeling was used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs for prostate cancer in relation to plasma levels of isoflavone. Although plasma daidzein showed no association, the highest tertile for plasma equol was significantly associated with a decreased risk of localized cancer, with ORs in the highest group of plasma genistein and equol compared with the lowest group of 0.54 (95% CI, 0.29–1.01; Ptrend = 0.03) and 0.43 (95% CI, 0.22–0.82; Ptrend = 0.02), respectively. Plasma isoflavone levels were not significantly associated with the risk of advanced prostate cancer. The results of this study were consistent with the results of our study about the inverse association between localized prostate cancer and soy and isoflavone intake.

6. Green tea

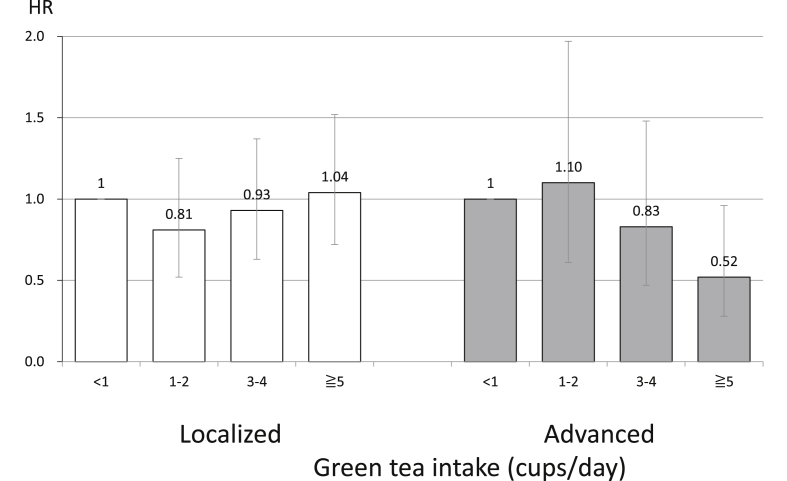

The association of green tea intake with prostate cancer is shown in Fig. 3.15

Fig. 3. The association between green tea intake and prostate cancer according to stage in Japanese men.15 The error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. HR, hazard ratio.

The World Cancer Research Fund International's Continuous Update Project concluded that data were insufficient to draw a conclusion for the association between green tea intake and prostate cancer.10 In general, green tea has a high content of catechins, which play an important role in cancer prevention. Given the high consumption of green tea in Asia, it has been suggested that the low incidence of prostate cancer among Asians may be partly due to the effects of green tea. We conducted a cohort analysis of the possible association between green tea and prostate cancer risk among 49,920 men aged 40–69 years who completed a questionnaire and were followed from 1990 to 2004. During this time, 404 men were newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, of whom 114 had advanced cases, 271 had localized cases, and 19 were of an undetermined stage. Green tea was not associated with localized prostate cancer. However, green tea consumption was associated with a dose-dependent decrease in the risk of advanced prostate cancer. The HR was 0.52 (95% CI, 0.28–0.96) for men drinking ≥5 cups/day compared with those consuming <1 cup/day (Ptrend = 0.01). Green tea may be associated with a decreased risk of advanced prostate cancer.

7. Conclusion

We elucidated the association of various lifestyle factors with prostate cancer according to stage in Japanese men (Table 1).16–21 However, epidemiological study of prostate cancer is insufficient, and more evidence for the prevention of prostate cancer in Japan is needed.

Table 1. Summary of the association between lifestyle, diet, and prostate cancer in the JPHC Study.

| Risk factor | Reference | Results from JPHC study | International evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Localized | Advanced | |||

| Smoking | 9 | NA | ↑suggestive | ↑suggestive (death)a |

| Alcohol | 9 | NA | ↑ | Limited-no conclusionb |

| Body fatness | 16 | NA | NA | ↑Probable (advanced)b |

| Soy | 13 | ↓ | ↑suggestive | Limited-no conclusionb |

| Green tea | 15 | NA | ↓ | Limited-no conclusionb |

| Dairy food | 17 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑Limited-suggestiveb |

| Saturated fatty acid | 17 | ↑ | ↑ | Limited-no conclusionb |

| Calcium | 17 | ↑suggestive | ↑suggestive | ↑Limited-suggestiveb |

| Fruits and Vegetables | 18 | NA | NA | Limited-no conclusionb |

| Fiber | 19 | NA | ↓ | Limited-no conclusionb |

| Isoflavone in plasma | 14 | ↓ | ↑suggestive | – |

| Testosterone in plasma | 20 | NA | NA | – |

| Sex hormone binding globulin in plasma | 20 | ↑suggestive | ↑suggestive | – |

| Organochlorines in plasma | 21 | NA | NA | – |

JPHC, Japan Public Health Center; NA, no association.

The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014.

World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Report. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Prostate Cancer. [Internet,http://www.wcrf.org/int/research-we-fund/continuous-update-project-findings-reports/prostate-cancer]. AICR. 2011 [cited 2016 April 1].

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Dr. Shoichiro Tsugane, principal investigator, and all the other scientists and staff in the research group of the JPHC study. The author also thanks the Japan Epidemiological Association and the Editorial Board of the Journal of Epidemiology for the opportunity to write this article.

This study was supported by National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (23-A-31[toku] and 26-A-2) (since 2011) and a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (from 1989 to 2010).

Study personnel: members of the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study (JPHC Study, principal investigator: S. Tsugane) Group are: S. Tsugane, N. Sawada, M. Iwasaki, S. Sasazuki, T. Yamaji, T. Shimazu and T. Hanaoka, National Cancer Center, Tokyo; J. Ogata, S. Baba, T. Mannami, A. Okayama, and Y. Kokubo, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, Osaka; K. Miyakawa, F. Saito, A. Koizumi, Y. Sano, I. Hashimoto, T. Ikuta, Y. Tanaba, H. Sato, Y. Roppongi, T. Takashima and H. Suzuki, Iwate Prefectural Ninohe Public Health Center, Iwate; Y. Miyajima, N. Suzuki, S. Nagasawa, Y. Furusugi, N. Nagai, Y. Ito, S. Komatsu and T. Minamizono, Akita Prefectural Yokote Public Health Center, Akita; H. Sanada, Y. Hatayama, F. Kobayashi, H. Uchino, Y. Shirai, T. Kondo, R. Sasaki, Y. Watanabe, Y. Miyagawa, Y. Kobayashi, M. Machida, K. Kobayashi and M. Tsukada, Nagano Prefectural Saku Public Health Center, Nagano; Y. Kishimoto, E. Takara, T. Fukuyama, M. Kinjo, M. Irei, and H. Sakiyama, Okinawa Prefectural Chubu Public Health Center, Okinawa; K. Imoto, H. Yazawa, T. Seo, A. Seiko, F. Ito, F. Shoji and R. Saito, Katsushika Public Health Center, Tokyo; A. Murata, K. Minato, K. Motegi, T. Fujieda and S. Yamato, Ibaraki Prefectural Mito Public Health Center, Ibaraki; K. Matsui, T. Abe, M. Katagiri, M. Suzuki, and K. Matsui, Niigata Prefectural Kashiwazaki and Nagaoka Public Health Center, Niigata; M. Doi, A. Terao, Y. Ishikawa, and T. Tagami, Kochi Prefectural Chuo-higashi Public Health Center, Kochi; H. Sueta, H. Doi, M. Urata, N. Okamoto, F. Ide, H. Goto and R Fujita, Nagasaki Prefectural Kamigoto Public Health Center, Nagasaki; H. Sakiyama, N. Onga, H. Takaesu, M. Uehara, T. Nakasone and M. Yamakawa, Okinawa Prefectural Miyako Public Health Center, Okinawa; F. Horii, I. Asano, H. Yamaguchi, K. Aoki, S. Maruyama, M. Ichii, and M. Takano, Osaka Prefectural Suita Public Health Center, Osaka; Y. Tsubono, Tohoku University, Miyagi; K. Suzuki, Research Institute for Brain and Blood Vessels Akita, Akita; Y. Honda, K. Yamagishi, S. Sakurai and N. Tsuchiya, University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki; M. Kabuto, National Institute for Environmental Studies, Ibaraki; M. Yamaguchi, Y. Matsumura, S. Sasaki, and S. Watanabe, National Institute of Health and Nutrition, Tokyo; M. Akabane, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Tokyo; T. Kadowaki and M. Inoue, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo; M. Noda and T. Mizoue, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo; Y. Kawaguchi, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo; Y. Takashima and Y. Yoshida, Kyorin University, Tokyo; K. Nakamura and R. Takachi, Niigata University, Niigata; J. Ishihara, Sagami Women's University, Kanagawa; S. Matsushima and S. Natsukawa, Saku General Hospital, Nagano; H. Shimizu, Sakihae Institute, Gifu; H. Sugimura, Hamamatsu University School of Medicine, Shizuoka; S. Tominaga, Aichi Cancer Center, Aichi; N. Hamajima, Nagoya University, Aichi; H. Iso and T. Sobue, Osaka University, Osaka; M. Iida, W. Ajiki, and A. Ioka, Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease, Osaka; S. Sato, Chiba Prefectural Institute of Public Health, Chiba; E. Maruyama, Kobe University, Hyogo; M. Konishi, K. Okada, and I. Saito, Ehime University, Ehime; N. Yasuda, Kochi University, Kochi; S. Kono, Kyushu University, Fukuoka; S. Akiba, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima; T. Isobe, Keio University, Tokyo; Y. Sato, Tokyo Gakugei University, Tokyo.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsugane S, de Souza JM, Costa ML Jr, et al. Cancer incidence rates among Japanese immigrants in the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1969-78. Cancer Causes Control. 1990;1:189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimizu H, Ross RK, Bernstein L, Yatani R, Henderson BE, Mack TM. Cancers of the prostate and breast among Japanese and white immigrants in Los Angeles County. Br J Cancer. 1991;63:963–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yatani R, Kusano I, Shiraishi T, Hayashi T, Stemmermann GN. Latent prostatic carcinoma: pathological and epidemiological aspects. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1989;19:319–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muir CS, Nectoux J, Staszewski J. The epidemiology of prostatic cancer. Geographical distribution and time-trends. Acta Oncol. 1991;30:133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickey K, Do KA, Green A. Smoking and prostate cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 2001;23:115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Editorial Board of the Cancer Statistics in Japan Cancer Statistics in Japan-2015. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsugane S, Sawada N. The JPHC study: design and some findings on the typical Japanese diet. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:777–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawada N, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, et al. Alcohol and smoking and subsequent risk of prostate cancer in Japanese men: the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Cancer Research Fund International’s Continuous Update Project Prostate cancer. World Research Cancer Fund; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Secretan B, Straif K, Baan R, et al. A review of human carcinogens–Part E: tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1033–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surgeon General Report The Health Consequences of Smoking -- 50 Years of Progress. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurahashi N, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, et al. Soy product and isoflavone consumption in relation to prostate cancer in Japanese men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:538–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurahashi N, Iwasaki M, Inoue M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane S. Plasma isoflavones and subsequent risk of prostate cancer in a nested case-control study: the Japan Public Health Center. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5923–5929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurahashi N, Sasazuki S, Iwasaki M, Inoue M, Tsugane S, Group JS. Green tea consumption and prostate cancer risk in Japanese men: a prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurahashi N, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Otani T, Inoue M, Tsugane S. Association of body mass index and height with risk of prostate cancer among middle-aged Japanese men. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:740–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurahashi N, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane AS. Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study G. Dairy product, saturated fatty acid, and calcium intake and prostate cancer in a prospective cohort of Japanese men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:930–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takachi R, Inoue M, Sawada N, et al. Fruits and vegetables in relation to prostate cancer in Japanese men: the Japan public health center-based prospective study. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62:30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawada N, Iwasaki M, Yamaji T, et al. Fiber intake and risk of subsequent prostate cancer in Japanese men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawada N, Iwasaki M, Inoue M, et al. Plasma testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin concentrations and the risk of prostate cancer among Japanese men: a nested case-control study. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2652–2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawada N, Iwasaki M, Inoue M, et al. Plasma organochlorines and subsequent risk of prostate cancer in Japanese men: a nested case-control study. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:659–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]