Abstract

Background

Subjects with prehypertension (pre-HT; 120/80 to 139/89 mm Hg) have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD); however, whether the risk of pre-HT can be seen at the pre-HT status or only after progression to a hypertensive (HT; ≥140/90 mm Hg) state during the follow-up period is unknown.

Methods

The Jichi Medical Cohort study enrolled 12,490 subjects recruited from a Japanese general population. Of those, 2227 subjects whose BP data at baseline and at the middle of follow-up and tracking of CVD events were available (median follow-up period: 11.8 years). We evaluated the risk of HT in those with normal BP or pre-HT at baseline whose BP progressed to HT at the middle of follow-up compared with those whose BP remained at normal or pre-HT levels.

Results

Among the 707 normotensive patients at baseline, 34.1% and 6.6% of subjects progressed to pre-HT and HT, respectively, by the middle of follow-up. Among 702 subjects with pre-HT at baseline, 26.1% progressed to HT. During the follow-up period, there were 11 CVD events in normotensive patients and 16 CVD events in pre-HT patients at baseline. The subjects who progressed from pre-HT to HT had 2.95 times higher risk of CVD than those who remained at normal BP or pre-HT in a multivariable-adjusted Cox hazard model.

Conclusion

This relatively long-term prospective cohort study indicated that the CVD risk with pre-HT might increase after progression to HT; however, the number of CVD events was small. Therefore, the results need to be confirmed in a larger cohort.

Keywords: Prehypertension, Japanese, Cardiovascular disease, Population-based study

1. Introduction

Prehypertension (pre-HT), defined as a blood pressure (BP) of 120–139/80–89 mm Hg, has been considered to be associated with risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1–3 Therefore, lifestyle modification interventions in subjects with pre-HT have been performed. Additionally, the results of the Trial of Preventing Hypertension (TROPHY) study,4 in which candesartan was administered to subjects with pre-HT, have raised the question of whether or not antihypertensive treatment for pre-HT is necessary.

We previously reported that pre-HT at baseline was associated with a 45% higher risk of CVD events than normal BP after adjusting for traditional CVD risk factors. In the population evaluated in this study, the risk of CVD among pre-HT patients was increased, especially among non-elderly subjects, after more than 5 years of follow-up,5 suggesting that the risk of pre-HT might be seen after their BP progressed to HT. However, it was not clear how their BP had changed by the middle of the follow-up period.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to clarify whether the CVD risk of pre-HT can be seen in subjects with or without progression to HT among study subjects for whom BP data were available in the middle of the follow-up period.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

The Jichi Medical School (JMS) Cohort Study has been conducted in 12 rural areas across Japan since 1992. The study subjects were enrolled from the medical checkup system for CVD in accordance with the Health and Medical Service Law for the Aged. A municipal government office in each community sent invitations to all dwelling adults.

The present study, a population-based prospective cohort study, enrolled 12,490 subjects at baseline between April 1992 and July 1995 to investigate risk factors for CVD, including myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke. After the exclusion of 442 subjects with insufficient BP information, 746 subjects with a history of receiving medication for HT, 159 with a history of CVD, 52 subjects with atrial fibrillation by ECG at baseline, and 91 who could not be completely tracked for CVD events were excluded at follow-up. Therefore, the total number of baseline subjects whose CVD risk was able to be evaluated was 11,000. Although we need BP data at the middle of follow-up to evaluate the risk of BP progression in this study, the middle BP data could be obtained from only seven areas (Iwaizumi, Kuze, Takasu, Wara, Sakugi, Ainoshima, and Akaike). Therefore, we additionally excluded subjects for whom no information had been collected in 1999 (8127), those who were unable to provide sufficient information about BP in 1999 (613), and those in whom CVD had already occurred before 1999 (33). After applying these exclusions, the eligible sample for the current study consisted of 2227 subjects.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jichi Medical University School of Medicine and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

2.2. Blood pressure

BP was measured once using a fully automated device (BP203RV-II; Nippon Colin, Komaki, Japan)6 placed on the right arm of the subject after a seated 5-min rest period. Subjects were classified as having normal BP (systolic BP [SBP]/diastolic BP [DBP] <120/80 mm Hg), pre-HT (SBP 120–139 mm Hg and/or DBP 80–89 mm Hg), or HT (SPB/DPB ≥140/90 mm Hg or medicated for HT) according to the definitions of the Joint National Committee 7 (JNC7). Subjects who used antihypertensive medications at baseline were classified as having HT.

BP data at follow-up were obtained in 1999 from seven areas. The subjects were residents aged 40–69 years in five areas, those aged >35 years in one area, and those aged 20–90 years in another area. We could not obtain information about medications for HT in 1999, so we applied the information about the administration of antihypertensive medications at baseline to categorize the BP group in 1999.

2.3. Variables

Obesity was defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2. Total cholesterol levels were measured using an enzymatic method (Wako, Osaka, Japan; interassay coefficient of variability [CV]: 1.5%). We defined hyperlipidemia as total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL or being medicated for hyperlipidemia. Blood glucose was measured using an enzymatic method (Kanto Chemistry, Tokyo, Japan; interassay CV: 1.9%). We defined impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) as fasting blood glucose levels between 100 and 125 mg/dL or postprandial glucose levels between 140 and 199 mg/dL. We defined diabetes mellitus (DM) as fasting blood glucose levels ≥126 mg/dL or a postprandial glucose levels ≥200 mg/dL.

Trained interviewers obtained medical history and lifestyle by using a standardized questionnaire. Subjects whose father or mother had HT were defined as having a family history of HT. Smoking status was classified as current smoker or not. An alcohol habit was defined as drinking more than 20 g of alcohol per day for ≥4 days per week.

2.4. Follow-up

The annual medical checkup system was also used to follow the subjects. At each follow-up, medical records were checked to determine whether the subjects had stroke or MI events. We contacted those who did not come to the health checkup by mail or phone. Public health nurses also visited them to obtain additional information. If the subjects were suspected to have developed stroke, duplicate computer tomography scans was performed, while electrocardiograms were performed for those suspected to have developed MI.

2.5. Diagnostic criteria

Stroke was defined as the onset of a focal and nonconvulsive neurological deficit lasting more than 24 h.7 MI was defined based on the World Health Organization Multinational Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in the Cardiovascular Disease (MONICA) Project criteria.8 A diagnosis committee consisting of one radiologist, one neurologist, and two cardiologists diagnosed stroke and MI independently.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Differences in mean values among the normal BP, pre-HT, and HT groups were tested using analysis of variance. Tukey's honestly significant difference test was used for intergroup differences. Differences in percentages among these groups were estimated using a chi-square test. The Kaplan-Meier method was applied for each BP group, and comparisons were made using the log-rank test. P values were calculated using the log-rank test. We used the multivariable adjusted Cox hazard model as a tool to assess the risk of CVD. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Subjects

The characteristics of the subjects in the whole JMS study population have been reported previously.9 Of these, BP data were available for 2227 subjects during the middle of the follow-up period for this study. The prevalence rates of subjects with normal BP, pre-HT, and HT by the classifications of JNC7 were 31.7% (n = 707), 31.5% (n = 702), and 36.7% (n = 818), respectively. Of the 2227 subjects included in the present analysis, 37.5% (n = 836) were males. The mean (standard deviation) for age was 56.0 (10.1) years. Subjects aged 65 years or older (n = 486) constituted 21.8% of the sample. The percentage of subjects with obesity was 23.8% (n = 529). The prevalence rates of hyperlipidemia, IGT, and diabetes were 9.6% (n = 214), 15.5% (n = 346), and 3.5% (n = 79), respectively. The percentage of subjects with an alcohol drinking habit was 19.8% (n = 441), and the percentage of subjects who currently smoked was 18.9% (n = 442). The percentage of subjects using hypertensive drugs was 13.1% (n = 291). The number of area dwellings were 688 (30.9%) for Wara, 576 (25.9%) for Takasu, 291 (13.0%) for Iwaizumi, 286 (12.8%) for Kuze, 188 (8.4%) for Akaike, 124 (5.6%) for Sakugi, and 74 (3.3%) for Ainoshima.

3.2. The characteristics of subjects in each hypertensive group

The characteristics of subjects in the hypertensive groups by JNC7 classification (i.e., normal BP, pre-HT, and HT) are shown in Table 1. The age, SBP, DBP, and percentages of males, obesity, those with family history of HT, current smokers, alcohol drinkers, IGT, DM, and hyperlipidemia in the pre-HT subjects were significantly higher than those in the normal BP subjects. The percentage of current smokers in the pre-HT subjects was significantly lower than in the normal BP subjects. The percentages of area dwellings in each BP group were different.

Table 1. Participant characteristics by BP group.

| Normal BP | Pre-HT | HT | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 707 | n = 702 | n = 818 | ||

| Age, years | 52.7 (10.6) | 54.9 (10.2)** | 59.8 (8.2)†† | <0.001 |

| Men, % | 33.5 | 37.2 | 41.3 | 0.007 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 107.6 (8.0) | 128.5 (5.6)** | 152.2 (14.8)†† | <0.001 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 66.0 (6.6) | 76.8 (6.3)** | 89.1 (10.0)†† | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 11.7 | 24.7 | 34.1 | <0.001 |

| Family History of HT, % | 23.5 | 26.7 | 33.9 | <0.001 |

| Current smokers, % | 22.7 | 19.2 | 16.1 | 0.005 |

| Alcohol habits, % | 16.8 | 21.6 | 23.6 | 0.005 |

| Glycemia | ||||

| IGT, % | 9.3 | 15.2 | 21.6 | <0.001 |

| DM, % | 1.3 | 2.7 | 6.3 | |

| Hyperlipidemia, % | 6.4 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 0.001 |

| Areas | ||||

| Iwaizumi | 9.5 | 10.7 | 18.2 | <0.001 |

| Kuze | 13.6 | 13.0 | 12.1 | |

| Takasu | 25.3 | 28.2 | 24.3 | |

| Wara | 37.5 | 28.8 | 27.0 | |

| Sakugi | 4.7 | 6.0 | 6.0 | |

| Ainoshima | 2.5 | 3.4 | 3.9 | |

| Akaike | 6.9 | 10.0 | 8.4 |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HT, hypertension; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data are shown as mean (standard deviation) or percentage. Comparison among subjects classified as normal BP, pre-HT and HT were calculated by ANOVA or chi square test. Probability <0.05 was considered significant. Intergroup differences were calculated by Tukey's honestly significant differences test or by Bonferroni-corrected chi-square test.

*, pre-HT vs. normal BP or HT vs. normal (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001); †, HT vs. pre-HT; (†, p < 0.05; ††, p < 0.001).

3.3. Changes in hypertensive status

Among the normotensive subjects at baseline (n = 707), 419 subjects (59.3%) remained normotensive, 241 subjects (34.1%) progressed to pre-HT, and 47 subjects (6.6%) progressed to HT by the middle of the follow-up period. Among the subjects with pre-HT at baseline (n = 702), 188 subjects (26.8%) became normotensive, 331 subjects (47.2%) remained at pre-HT, and 183 subjects (26.1%) progressed to HT by the middle of the follow-up period. Among the subjects with HT at baseline (n = 818), 64 subjects (7.8%) entered the normotensive range, 158 subjects (19.3%) entered the pre-HT range, and 596 subjects (72.9%) remained in the HT range or received antihypertensive medication. Comparison of the characteristics of the subjects in each hypertension group at baseline and the middle of the follow-up period is shown separately for those who had normotension, pre-HT, and HT at baseline (Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4). In the subjects with normal BP at baseline, the age, SBP, DBP, and percentages of men and those with alcohol habits in subjects with HT at the middle of follow-up were significantly higher than in those who maintained normal BP at the middle of follow-up. In those with pre-HT at baseline, the age, SBP, and DBP in subjects with HT at the middle of follow-up were significantly higher than in those with normal BP.

Table 2. Characteristics of normotensive patients at the middle of follow-up among those normal BP group at baseline (n = 707).

| BP group at baseline | Normal BP (n = 707) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP group at middle of follow-up | Normal BP | Pre-HT | HT | |

| 419 (59.3) | 241 (34.1) | 47 (6.6) | ||

| Age, years | 51.7 (10.7) | 53.6 (10.5) | 57.2 (8.3)† | 0.001 |

| Men | 28.6 | 39.1 | 48.9 | 0.002 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 105.8 (8.3) | 109.8 (6.8)** | 111.9 (6.1)†† | <0.001 |

| Follow-up period, years | 11.7 (1.01) | 11.7 (0.94) | 11.7 (1.34) | 0.10 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 64.6 (6.4) | 66.9 (6.6)** | 70.5 (5.8)†† | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 11.0 | 13.1 | 10.9 | 0.71 |

| Family history of HT | 20.6 | 28.8 | 21.7 | 0.06 |

| Current smokers | 20.0 | 27.3 | 23.4 | 0.10 |

| Alcohol habit | 13.3 | 21.1 | 26.1 | 0.01 |

| Glycemia | ||||

| IGT | 8.5 | 10.9 | 8.5 | 0.73 |

| DM | 1.0 | 1.7 | 2.1 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 7.2 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 0.56 |

BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data are shown as mean (standard deviation) or percentage. Comparison among subjects classified as normal BP, pre-HT, and HT was performed by ANOVA or chi-square test. Intergroup differences were calculated by Tukey's honestly significant differences test or by Bonferroni-corrected chi-square test. *, pre-HT vs. normal BP or HT vs. normal (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01); †, HT vs. pre-HT (†, p < 0.05; ††, p < 0.01).

Table 3. Characteristics of normotensive patients at the middle of follow-up among those with pre-HT at baseline (n=702).

| BP group at baseline | Pre-HT (n = 702) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP group at middle | Normal BP | Pre-HT | HT | |

| 188 (26.8) | 331 (47.2) | 183 (26.1) | ||

| Age, years | 52.6 (10.5) | 55.1 (10.1)* | 56.8 (9.8)†† | <0.001 |

| Men | 34.0 | 37.2 | 40.4 | 0.44 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 127.1 (5.7) | 128.4 (5.5)* | 130.3 (5.3)†† | <0.001 |

| Follow-up period, years | 11.6 (1.11) | 11.7 (1.01) | 11.7 (1.11) | 0.17 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 75.6 (6.4) | 76.6 (6.3)** | 78.3 (6.1)†† | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 23.2 | 25.2 | 25.3 | 0.86 |

| Family history of HT | 28.2 | 24.1 | 30.1 | 0.30 |

| Current smokers | 18.3 | 20.9 | 17.0 | 0.54 |

| Alcohol habit | 20.1 | 21.3 | 23.7 | 0.69 |

| Glycemia | ||||

| IGT | 14.0 | 15.8 | 15.4 | 0.07 |

| DM | 0.5 | 4.5 | 1.6 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 9.7 | 12.4 | 11.0 | 0.65 |

BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data are shown as mean (standard deviation) or percentage. Comparison among subjects classified as normal BP, pre-HT, and HT was performed by ANOVA or chi-square test. Intergroup differences were calculated by Tukey's honestly significant differences test or by Bonferroni-corrected chi-square test. *, pre-HT vs. normal BP or HT vs. normal (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01); †, HT vs. pre-HT (†, p < 0.05; ††, p < 0.01).

Table 4. Characteristics of hypertensive patients at the middle of follow-up among those with HT at baseline (n=818).

| BP group at baseline | HT (n = 818) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP group at middle | Normal BP | Pre-HT | HT | |

| 64 (7.8) | 158 (19.3) | 596 (72.9) | ||

| Age, years | 59.8 (8.3) | 57.7 (9.6) | 60.3 (7.7) | 0.002 |

| Men | 34.4 | 38.6 | 42.8 | 0.32 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 146.6 (15.0) | 150.7 (10.1) | 153.2 (15.6)†† | 0.001 |

| Follow-up period, years | 11.5 (0.90) | 11.3 (1.16) | 11.5 (1.30) | 0.43 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 83.1 (8.4) | 87.4 (8.1)** | 90.1 (10.4)†† | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 34.9 | 30.1 | 35.1 | 0.51 |

| Family history of HT | 25.0 | 35.1 | 34.5 | 0.32 |

| Current smokers | 16.1 | 14.1 | 16.6 | 0.75 |

| Alcohol habit | 16.4 | 16.3 | 26.3 | 0.02 |

| Glycemia | ||||

| IGT | 23.8 | 18.7 | 22.1 | 0.81 |

| DM | 7.9 | 7.1 | 5.9 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 12.9 | 11.5 | 11.1 | 0.92 |

BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data are shown as mean (standard deviation) or percentage. Comparison among subjects classified as normal BP, pre-HT, and HT was performed by ANOVA or chi-square test. Intergroup differences were calculated by Tukey's honestly significant differences test or by Bonferroni-corrected chi-square test. *, pre-HT vs. normal BP or HT vs. normal (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01); †, HT vs. pre-HT (†, p < 0.05; ††, p < 0.01).

Additionally, the incidence of HT was significantly associated with being in the BP category of pre-HT (HR 3.57; 95% CI, 2.56–4.88) and HT (HR 9.17; 95% CI, 6.67–12.61), older age (per 10-year increment, HR1.16; 95% CI, 1.07–1.27), having a family history of HT (HR 1.26; 95% CI, 1.07–1.48), and drinking alcohol (HR 1.32; 95% CI, 1.07–1.61) (Table 5).

Table 5. The risk of having HT at the middle of the follow-up period in the normal BP and pre-HT groups at baseline.

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| BP group | |||

| Pre-HT | 3.57 | 2.56–4.99 | <0.01 |

| HT | 9.17 | 6.67–12.61 | <0.01 |

| Age, per 10-year increment | 1.16 | 1.07–1.27 | <0.01 |

| Gender, female = 0, male = 1 | 1.06 | 0.88–1.28 | 0.52 |

| Obesity | 1.00 | 0.85–1.18 | 0.99 |

| Family history of HT | 1.26 | 1.07–1.48 | <0.01 |

| Current smoking | 0.83 | 0.67–1.03 | 0.09 |

| Alcohol drinking habit | 1.32 | 1.07–1.61 | 0.01 |

| Glycemia | |||

| IGT | 1.10 | 0.91–1.32 | 0.32 |

| Diabetes | 0.84 | 0.60–1.19 | 0.33 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.11 | 0.88–1.40 | 0.37 |

BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; HT, hypertension; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance.

HRs, 95% CIs, and P values are based on Cox regression analysis adjusted for BP group, age by 10-year increments, obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2), family history of HT, current smoking, alcohol drinking habit, glycemia, and hyperlipidemia.

3.4. Follow-up of CVD events

The median length of follow-up was 11.8 years (25,806 person-years). During the follow-up period, there were 68 CVD events in 67 patients (57 strokes and 11 MIs, including 1 subject with both stroke and MI). There were 11 CVD events in subjects who had normotension at baseline, 16 events in those who had pre-HT, and 40 events in those who had HT.

3.5. BP progression and the risk of CVD in subjects with normotension at baseline

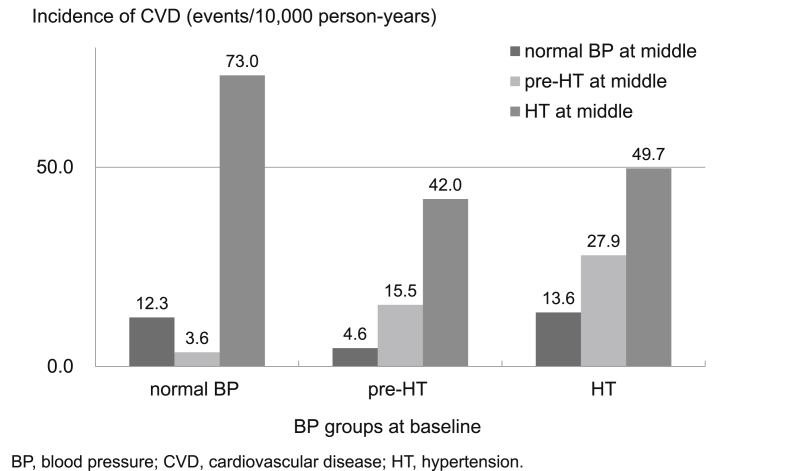

Among the normotensive subjects at baseline, the incidences of CVD (per 10,000 person-years) were 12.3 for those who remained normotensive, 3.6 for those who progressed to pre-HT, and 73.0 for those who progressed to HT by the middle of the follow-up period (Fig. 1). Among the subjects with normal BP at baseline, the subjects who progressed to HT by the middle of the follow-up period had higher risk of CVD than those who retained normal BP (HR 7.68; 95% CI, 1.43–41.23), while those who progressed to pre-HT did not have an increased risk in comparison to those who retained normal BP in the multivariable-adjusted Cox hazard model (HR 0.13; 95% CI, 0.01–1.51) (Table 6).

Fig. 1. Incidence of CVD in each BP group at the middle of follow-up, by BP group at baseline. BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HT, hypertension.

Table 6. Incidence and risk of CVD of BP groups at the middle of follow-up, by baseline BP group.

| BP groups | Number of events | Incidencea | Non-adjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At baseline | At middle | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Normal BP (n = 707) | Normal BP (n = 419) | 6 | 12.3 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Ref. | ||

| Pre-HT (n = 241) | 1 | 3.6 | 0.29 | 0.03–2.41 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.01–1.51 | 0.10 | |

| HT (n = 47) | 4 | 73.0 | 5.97 | 1.69–21.17 | 0.006 | 7.68 | 1.43–41.23 | 0.018 | |

| Pre-HT (n = 702) | Normal BP or pre-HT (n = 519) | 7 | 11.6 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Ref. | ||

| HT (n = 183) | 9 | 42.0 | 3.53 | 1.31–9.50 | 0.012 | 2.95 | 1.05–8.33 | 0.041 | |

BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio; HT, hypertension.

HRs, 95% CIs, and P values are based on Cox regression analysis adjusted for age/10-year increment, gender, obesity, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, alcohol drinking habits, smoking, family history of HT, and area.

Number of events/10,000 person-years.

3.6. BP progression and the risk of CVD in subjects with pre-HT at baseline

Among the pre-HT subjects, the incidences of CVD (per 10,000 person-years) at the middle of the follow-up period were 11.6 for the subjects who improved to normotension or remained at pre-HT and 42.0 for those who progressed to HT (Fig. 1). The risk of CVD in the subjects whose BP progressed from pre-HT to HT was significantly higher than in those who remained normotensive or with pre-HT in the multivariable-adjusted Cox hazard model (HR 2.95; 95% CI, 1.05–8.33) (Table 6).

4. Discussion

Subjects who had pre-HT at baseline and those who progressed to HT by the middle of the follow-up period had 2.95 times higher risk than those who did not progress to HT. Moreover, among the subjects who had normotension at baseline, those who progressed to HT by the middle of the follow-up period had 7.68 times higher risk of CVD than those who remained in the normal BP range. These results indicate that subjects within the range of non-HT at baseline could have an increased risk of CVD after their BP progressed to HT during the follow-up period.

Incidence of HT in the subjects with pre-HT at baseline was 3.57 times higher than in those with normal BP at baseline. Incidence of HT was also predicted by older age, alcohol drinking habit, and family history of HT. These results indicate that the accumulation of CVD risk factors affects the incident of HT and also suggest that, in order to prevent incidence of HT, lifestyle modification regarding alcohol drinking might be important, especially for older subjects. Alcohol drinking has been reported to reduce home BP at bedtime and increased BP in the morning hours.10 Alcohol drinking has also been associated with having resistant hypertension.11 Regular consumption of a small amount of alcohol has been reported to have a protective effect against the incidence of CVD12,13; however, the subjects in this study drank alcohol at as much as 20 g per day. Reducing the amount of alcohol consumed might be an important intervention for reducing incidence of HT and subsequent CVD events.

Additionally, in previous studies, metabolic factors were associated with the risk of having pre-HT. Di Bello et al. reported that early abnormalities of left ventricular (LV) longitudinal systolic deformation were found in pre-HT patients, together with mild LV diastolic dysfunction, which is associated with insulin resistance, systolic pressure load, and cardiac remodeling.14 Zeng et al. reported that baseline age, Mongolian ethnicity, alcohol drinking, overweight, high salt intake every day, inappropriate physical activity, and family history of HT were associated with the incidence of HT in China.15 Lee et al. reported that alcohol drinking, blue collar jobs, obesity, and hyperlipidemia were risk factors for pre-HT compared with normal BP. On the other hand, diabetes, obesity, and aging were reported as risk factors for HT compared with pre-HT.16 These previous studies suggest that there may be differences in the predictors based on differences of population characteristics and the kind of measurements used.

Several studies have attempted to clarify markers of BP progression. In the Strong Heart Study, progression to HT in 38% of pre-HT subjects could be predicted by higher LV mass and stroke volume in addition to baseline SBP and prevalent diabetes mellitus.17 Erdogan et al. reported that the baseline SBP, metabolic syndrome, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, presence of microalbuminuria, and a reflection of coronary microvascular function were markers to identify subjects with pre-HT at high risk for HT.18 Tomiyama et al. revealed that risk factors for HT in relatively young Japanese men with pre-HT were brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity and BMI.19

As we previously reported, subjects with pre-HT constituted one-third of our cohort, so the management of pre-HT is likely to be a heavy burden for public health. The subjects with pre-HT in the Japanese rural area that was the focus of this work who have a habit of drinking alcohol and a family history of HT should be managed.

4.1. Study limitations

There were some limitations in this study. First, we picked subjects (n = 2227) for this study who had available BP data during the middle of the follow-up period from among all available subjects for evaluation of the risk for CVD (n = 11,000). Therefore, the current data have some differences from the excluded data. Between the subjects in the current study (n = 2227) and those who were excluded (n = 8773), there were differences in age (56.0 [10.1] vs. 54.9 [11.8], p < 0.001), SBP (130.6 [21.2] vs. 129.0 [21.0] mm Hg, p < 0.001), and smoking habits (19.2% vs. 24.3%, p < 0.001). Second, we have a methodological limitation in BP measurements and categorization. We should have measured BP repeatedly, but this study was performed in annual health check-ups and BP was measured only once. Furthermore, we could not obtain information about medication in 1999 for the follow-up period. Instead, we used the information about medication at baseline, so the true number of HT subjects at follow-up might be greater than our estimate. Third, the number of CVD events was small (7 in subjects without BP progression, 9 in those with progression), limiting our ability to evaluate the risk of CVD.

4.2. Conclusion

In this Japanese population study, the risk of CVD events in subjects with pre-HT was increased after they developed HT during the follow-up period. Having HT by the middle of the follow-up period was associated with older age, alcohol drinking habit, having pre-HT, and having a family history of HT at baseline. These results suggest that the risk group with accumulation of those risk factors would be at particularly high risk of CVD events after relatively long-term follow-up. However, the results of this study should be confirmed by a larger cohort study because the number of CVD events was small.

Financial support

This research was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan Grant Number 13470096; and grants from the Foundation for the Development of the Community, Tochigi, Japan (S.I).

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. . The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takashima N, Ohkubo T, Miura K, et al. . Long-term risk of BP values above normal for cardiovascular mortality: a 24-year observation of japanese aged 30 to 92 years. J Hypertens. 2012;30:2299–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gu D, Chen J, Wu X, et al. . Prehypertension and risk of cardiovascular disease in chinese adults. J Hypertens. 2009;27:721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Julius S, Nesbitt SD, Egan BM, et al. . Feasibility of treating prehypertension with an angiotensin-receptor blocker. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1685–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishikawa Y, Ishikawa J, Ishikawa S, et al. . Prehypertension and the risk for cardiovascular disease in the japanese general population: the Jichi Medical School Cohort Study. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1630–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sekine MGE, Ochiai H, Umezu M, Ishii M. Office blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension. Ther Res. 1997;18:122. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. . Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The world health organization monica project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): a major international collaboration. WHO MINICA project principal investigators. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishikawa Y, Ishikawa J, Ishikawa S, et al. . Prevalence and determinants of prehypertension in a Japanese general population: the Jichi medical School cohort study. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:1323–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawano Y, Pontes CS, Abe H, Takishita S, Omae T. Effects of alcohol consumption and restriction on home blood pressure in hypertensive patients: serial changes in the morning and evening records. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2002;24:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarafidis PA, Bakris GL. Resistant hypertension: an overview of evaluation and treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1749–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iso H, Baba S, Mannami T, et al. . Alcohol consumption and risk of stroke among middle-aged men: the JPHC Study Cohort I. Stroke. 2004;35:1124–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beulens JW, Rimm EB, Ascherio A, et al. . Alcohol consumption and risk for coronary heart disease among men with hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Bello V, Talini E, Dell'Omo G, et al. . Early left ventricular mechanics abnormalities in prehypertension: a two-dimensional strain echocardiography study. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng L, Sun Z, Zhang X, et al. . Predictors of progression from prehypertension to hypertension among rural chinese adults: results from liaoning province. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JH, Hwang SY, Kim EJ, Kim MJ. Comparison of risk factors between prehypertension and hypertension in korean male industrial workers. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23:314–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Marco M, de Simone G, Roman MJ, et al. . Cardiovascular and metabolic predictors of progression of prehypertension into hypertension: the Strong Heart Study. Hypertension. 2009;54:974–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erdogan D, Ozaydin M, Icli A, et al. . Echocardiographic predictors of progression from prehypertension to hypertension. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1639–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomiyama H, Yamashina A. Arterial stiffness in prehypertension: a possible vicious cycle. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5:280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]