Abstract

Introduction

Retinal characteristics are increasingly recognized as biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases. Retinal thickness measured by optical coherence tomography may reflect the presence of Alzheimer's disease (AD). We performed a meta-analysis on retinal thickness in AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients and healthy controls (HCs).

Methods

We selected 25 studies with measurements of retinal thickness including 887 AD patients, 216 MCI patients, and 864 HCs that measured retinal thickness. Outcomes were peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and macular thickness. The main outcome was the standardized mean differences (SMDs). We used STATA to perform the meta-analysis (StataCorp, Texas; version 14.0).

Results

Relative to HCs, AD and MCI patients had lower peripapillary RNFL (SMD 0.98 [CI −1.30, −0.66, P < .0001] and SMD 0.71 [CI −1.24, −0.19, P = .008]). Total macular thickness was decreased in AD patients (SMD 0.88 [CI −1.12, −0.65, P = .000]).

Discussion

Retinal thickness is decreased in AD and MCI patients compared to HC. This confirms that neurodegenerative diseases may be reflected by retinal changes.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, Optical coherence tomography (OCT), Retinal thickness, Eye, Biomarkers, Alzheimer's disease (AD), Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia. It is neuropathologically characterized by amyloid-beta (Aβ)-plaques and neurofibrillary tangles containing tau. These neuropathological changes are believed to develop 15–20 years before symptom onset. AD is diagnosed in subjects with MCI or dementia using clinical criteria combined with abnormal biomarkers for Aβ pathology or neuronal injury [1], [2]. Aβ pathology is reflected by decreased Aβ levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or on an amyloid positron emission tomography (PET). Neuronal injury is reflected by either cortical atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), hypometabolism on fluorodeoxyglucose-PET (FDG-PET), or increased tau and/or phosphorylated tau (pTau) levels in CSF [3]. These biomarkers however, are invasive, expensive, or time consuming. Thus, there is an urgent need for an early, patient-friendly, inexpensive AD biomarker, that preferably detects AD pathology before severe neurodegeneration [4].

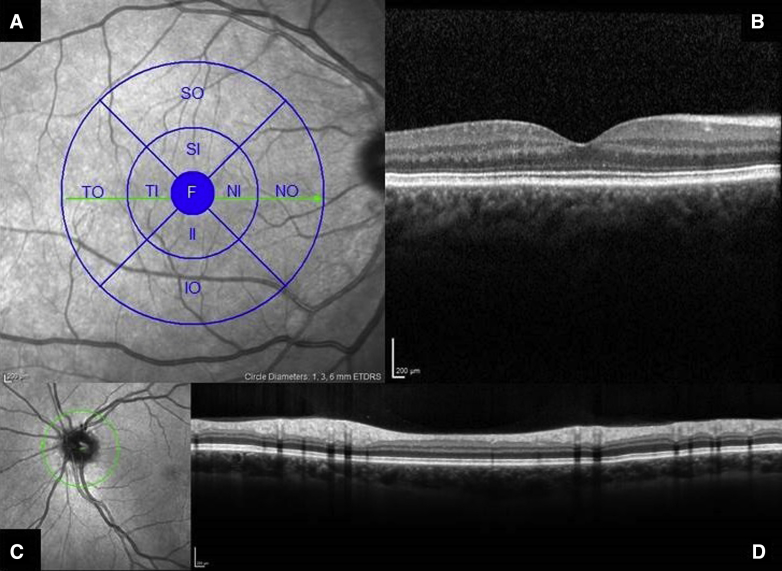

The retina is embryologically derived from the cranial part of the neural tube, similar to the brain, and therefore shares many similarities with its tissue. The retina is easily accessible, and retinal neurons can be visualized through high-resolution optical methods such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) visualizing thickness of retinal layers (Fig. 1). With OCT, retinal changes are visualized both in ophthalmological disease and in neurodegenerative disease. Previous studies have shown that the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness and ganglion cell layer (GCL) thickness are reduced in subjects with multiple sclerosis (MS) [5], Parkinson disease (PD) [6], and AD [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31].

Fig. 1.

Optical coherence tomography (Heidelberg Spectralis). OCT image of the macula (A) with an overlay of the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study regions and transversal OCT image showing the macula (B). Image of optic disk (C) and a transversal OCT image through the optic disk (D). Abbreviations: F, Fovea; II, inferior inner; IO, inferior outer; NI, nasal inner; NO, nasal outer; OCT, optical coherence tomography; SI, superior inner; SO, superior outer; TI, temporal inner; TO, nasal inferior.

In this study, we perform a meta-analysis to assess the retinal layer thickness in AD and MCI patients and cognitively normal subjects. OCT is an optical method that accurately measures retinal layer thickness and therefore potentially a patient-friendly noninvasive method for detection of neurodegenerative diseases. We also assess the role of concomitant ophthalmological disease on retinal thickness, in particular glaucoma and the possible confounding role of age and disease severity.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

We searched PubMed and EMBASE for studies analyzing OCT measurements in AD patients, MCI patients, and/or healthy controls (HCs) using the following search terms: “Alzheimer's Disease,” “senile dementia,” “Mild Cognitive Impairment,” “MCI,” “optical coherence tomography,” and “OCT” between 1990 and February 2016.

2.2. Inclusion

We included 25 studies that used NINCDS-ADRDA and/or DSMIV criteria for AD diagnosis, Petersen or Winblad criteria for MCI, and OCT to assess retinal layer thickness. Eight of these studies included an MCI group. Ten studies used first-generation time domain (TD)-OCT, and 15 studies used spectral domain (SD)-OCT. Twenty-four studies performed a peripapillary RNFL protocol (of which 16 studies presented data for separate quadrants). One study performed a macular protocol only, and six studies performed both a peripapillary and macular protocol. Eight studies included neuroimaging (MRI or CT), and two studies included CSF analysis (Table 1 characteristics of the included studies).

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| OCT∗ |

Subjects |

MMSE |

Age |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Study | Year | Scanner type | Protocols used | AD | MCI | HC | AD | HC | AD | HC |

| 1 | Pillai | 2016 | Cirrus 4000 HDOCT | Peripapillary RNFL | 21 | 20 | 34 | - | - | 65.80 | 65.10 |

| 2 | La Morgia | 2016 | Stratus OCT3 | Peripapillary RNFL | 21 | - | 74 | 18.3 | - | 71.20 | 69.10 |

| 3 | Garcia | 2015 | OCT1000 Topcon | Peripapillary RNFL Macular thickness |

23 | - | 28 | 23.3 | 28.2 | 79.30 | 72.30 |

| 4 | Eraslan | 2015 | RTVue 100 Fourier-domain | Peripapillary RNFL | 18 | - | 20 | - | - | 73.60 | 73.30 |

| 5 | Güneş | 2015 | OPKO/OTI SD-OCT | Peripapillary RNFL | 20 | - | 20 | - | - | 75.02 | 74.15 |

| 6 | Liu | 2015 | Stratus OCT3 | Peripapillary RNFL | 67 | 26 | 39 | - | - | 71.35 | 69.70 |

| 7 | Oktem | 2015 | Cirrus HDOCT | Peripapillary RNFL | 35 | 35 | 35 | 18 | 29 | 75.40 | 70.20 |

| 8 | Cheung | 2015 | Cirrus HDOCT | Peripapillary RNFL Macular GCL |

100 | 41 | 123 | - | - | 73.50 | 65.70 |

| 9 | Gao | 2015 | Cirrus HDOCT | Peripapillary RNFL | 25 | 26 | 21 | 19.24 | 28.57 | 74.72 | 72.05 |

| 10 | Bambo | 2015 | Cirrus HDOCT | Peripapillary RNFL | 56 | - | 56 | 16.56 | - | 74.00 | 76.40 |

| 11 | Larrossa | 2014 | Cirrus HDOCT Heidelberg Spectralis |

Peripapillary RNFL Macular thickness |

151 | - | 61 | 18.31 | - | 75.29 | 74.87 |

| 12 | Ascaso | 2014 | Stratus OCT3 | Peripapillary RNFL Macular thickness |

18 | 21 | 41 | 19.31 | 28.78 | 72.10 | 72.90 |

| 13 | Polo | 2014 | Cirrus HDOCT Heidelberg Spectralis |

Peripapillary RNFL Macular thickness |

70 | - | 70 | 15.96 | - | 74.15 | 73.98 |

| 14 | Gharbiya | 2014 | Heidelberg Spectralis | Peripapillary RNFL | 21 | - | 21 | 22.2 | 28.2 | 73.10 | 70.30 |

| 15 | Kromer | 2014 | Heidelberg Spectralis | Peripapillary RNFL | 22 | - | 22 | 22.59 | - | 75.90 | 64.00 |

| 16 | Moreno-Ramos | 2013 | OCT1000 Topcon | Peripapillary RNFL | 10 | - | 10 | 16.4 | 29.2 | 73.00 | 70.20 |

| 17 | Marziani | 2013 | RTVue Heidelberg Spectralis |

Macular thickness | 21 | - | 21 | - | - | 79.30 | 77.00 |

| 18 | Kirbas | 2013 | OCT1000 Topcon | Peripapillary RNFL | 40 | - | 40 | 18–25 | - | 69.30 | 68.90 |

| 19 | Moschos | 2012 | Stratus OCT3 | Peripapillary RNFL | 30 | - | 30 | - | - | 71.77 | - |

| 20 | Kesler | 2011 | Stratus OCT3 | Peripapillary RNFL | 30 | 24 | 24 | 23.6 | - | 73.70 | 70.90 |

| 21 | Lu | 2010 | Stratus OCT3 | Peripapillary RNFL | 22 | - | 22 | - | - | 73.00 | 68.00 |

| 22 | Paquet | 2007 | Stratus OCT3 | Peripapillary RNFL | 26 | 23 | 15 | 19.8 | 28.9 | 78.53 | 75.50 |

| 23 | Berisha | 2007 | Stratus OCT3 | Peripapillary RNFL | 9 | - | 8 | 23.8 | 29.5 | 74.30 | 74.30 |

| 24 | Iseri | 2006 | Stratus OCT3 | Peripapillary RNFL Macular thickness |

14 | - | 15 | 18.5 | 29.4 | 70.10 | 65.10 |

| 25 | Parisi | 2001 | Stratus OCT3 | Peripapillary RNFL | 17 | - | 14 | 16.38 | 23 | 70.37 | - |

| 887 | 216 | 864 | |||||||||

Abbreviations: OCT, optical coherence tomography; MMSE, Mini–Mental State Examination; AD, Alzheimer's disease; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; HC, healthy control; RNFL, retinal nerve fiber layer.

First-generation (time domain) OCT scanner is the stratus OCT3 and second-generation (spectral domain) OCT scanners are the Cirrus HDOCT, Heidelberg Spectralis, OPKO/OTI, OCT1000 Topcon, and RTVue.

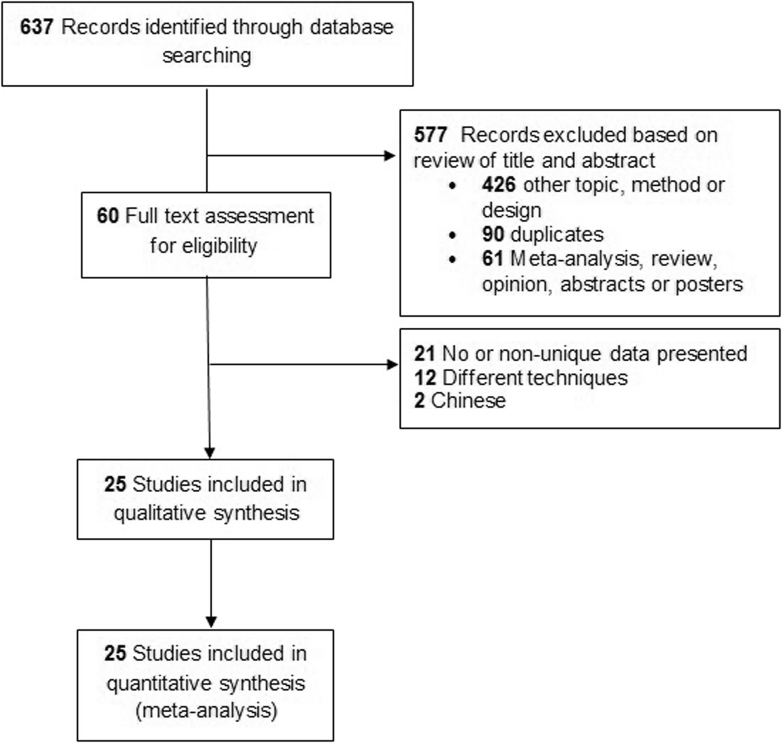

Of the 637 records identified, 612 were excluded due to their title, topic, method, or design. Others were excluded due to their abstracts, reviews, posters, communications in response to an article, or in the case of duplicate data. Studies with nondemented subjects or studies that use different techniques such as RNFL thickness with Heidelberg Retinal Tomography (HRT), fundus autofluorescence, and electroretinography were also excluded (Fig. 2 flowchart of included and excluded articles).

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of included and excluded articles.

2.3. Data extraction

We extracted mean and quadrant RNFL and macular thickness with standard deviations for AD and MCI patients and HC. In one study, data were presented as box plots [25]. Estimates of the mean and standard deviation were therefore calculated using the lower and upper quartiles, mean, and sample size following the methods described in Wan et al. [32]. A second study described RNFL thickness in bar diagrams without exact figures [27]. RNFL thickness means and standard deviations were therefore estimated with the help of the measure tool in Adobe Acrobat XI Pro (version 11.0.0). The standard errors were calculated to standard deviations.

2.4. Outcome measures

Peripapillary RNFL thickness was presented in superior, inferior, temporal, nasal, and mean quadrants. Total macular thickness was subdivided according to the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study regions; fovea, inner and outer ring.

2.5. Study quality rating

The QUADAS tool was used to assess the methodological quality for each study by two authors (J.d.H. and F.D.V.) (Supplementary Table 1) [33].

Glaucoma is an important potential confounder as it is a neurodegenerative disease of the retina resulting in RNFL loss. We therefore reviewed whether glaucoma was assessed by (1) medical history, (2) intraocular pressure, (3) bio microscopy, (4) fundus photographs, and/or (5) functional assessment in the form of visual field defects to generate a glaucoma exclusion score. All studies used ophthalmological history and intraocular pressure for the exclusion of glaucoma. However, this may not detect all cases, in particular normal tension glaucoma. Therefore, we totaled the number of additional assessments performed for exclusion of glaucoma: (1) posterior segment bio microscopy, (2) fundus photographs, and/or (3) functional assessment (visual fields). The higher the resulting glaucoma exclusion score, the more stringent the exclusion criteria for glaucoma were met (Supplementary Table 2).

2.6. Statistical analysis

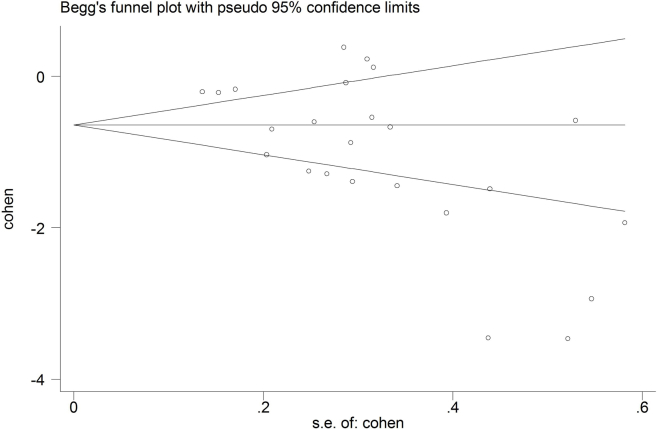

We used random-effects models for the meta-analysis with a main outcome measure of Cohen's d (standardized mean difference [SMD]). Heterogeneity was assessed by χ2 test, and Egger's regression test was used to test funnel plot asymmetry. A funnel plot was generated to assess publication bias and was statistically tested with Begg's and Egger's tests. We used STATA (StataCorp, Texas; version 14.0) for all analyses, with the metan command to create forest plots, the metabias command for funnel plot, and the metareg command to perform meta-regression.

Both univariate meta-regression and multivariate meta-regression were used to assess whether study characteristics were associated with the SMD. Meta-regression was carried out with the SMD as a dependent variable. Independent variables were as follows: OCT type (TD vs. SD), mean study Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) in the AD group, study glaucoma exclusion score, and mean study age. We performed subgroup analysis for first- and second-generation OCT scanner type (TD-OCT and SD-OCT, respectively) and for the four (superior, inferior, nasal, and temporal) peripapillary quadrants.

3. Results

3.1. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness

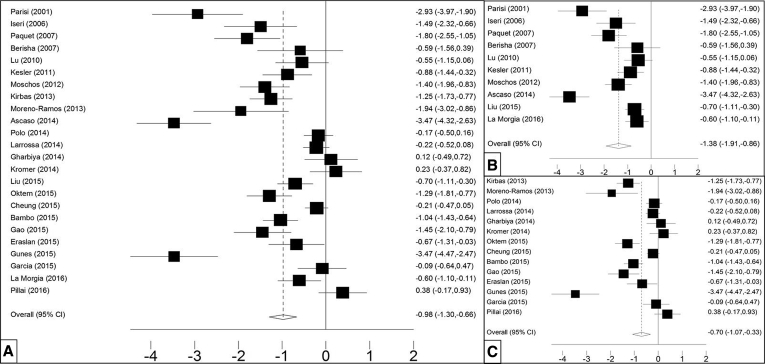

Mean peripapillary RNFL was described in 24 studies including 887 AD patients and 864 HCs. RNFL thickness was lower in AD versus HC (SMD −0.98 [CI −1.30, −0.66, P = .000), which corresponds to an absolute decrease of 9.70 μm (CI −10.76, −8.6, P = .000) (Fig. 3A). Fig. 3B and C show a larger effect for the TD than the SD scanner type, with effect estimates of respectively −1.38 (CI −1.91, −0.86, P = .000) and −0.70 (CI −1.07, −0.33, P = .000). Table 2 shows the differences between AD and HC for the mean peripapillary RNFL thickness and in the four quadrants in 20 studies. The superior and inferior quadrants are thinner than the nasal and temporal quadrants.

Fig. 3.

Mean peripapillary RNFL in AD and HC. Forest plots of standardized mean peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in (A) all studies (n = 24), (B) studies with time domain (TD)-OCT scanners (n = 10), and (C) spectral domain (SD)-OCT studies (n = 14). Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; HC, healthy control; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

Table 2.

Peripapillary RNFL in all quadrants (n = 20 studies)

| Peripapillary RNFL | Mean | Superior | Inferior | Nasal | Temporal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD versus HC | −0.95 [−1.29, −0.61] | −0.99 [−1.34, −0.65] | −0.81 [−1.13, −0.49] | −0.57 [−0.83, −0.30] | −0.42 [−0.63, −0.20] |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; HC, healthy control; RNFL, retinal nerve fiber layer.

NOTE. All P < .000.

NOTE. Standardized mean differences of peripapillary RNFL between study groups in all quadrants.

Eight studies measured peripapillary RNFL thickness including a MCI group consisting of 322 AD patients, 216 MCI patients, and 367 HCs and measured peripapillary RNFL thickness. RNFL thickness of the MCI group was between the RNFL thickness of AD patients and HC, with a standardized mean difference of −0.71 (CI −1.24, −0.19, P = .008) compared to controls and of −0.43 (CI −0.73, −0.13, P = .005) in comparison with AD patients.

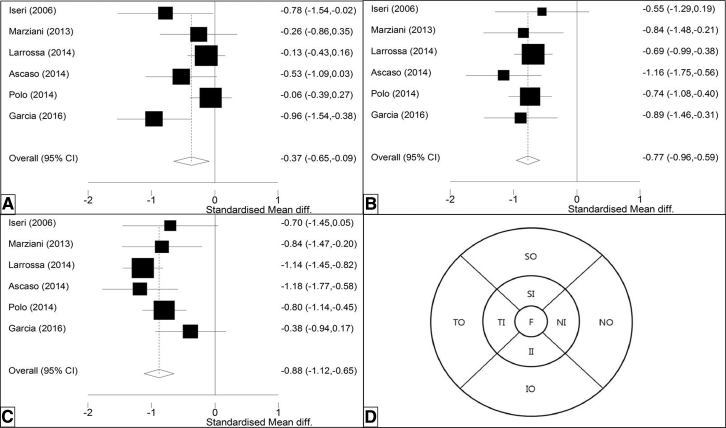

3.2. Macular thickness

Seven studies described macular thickness of 302 AD patients in total and 241 HCs, showing significant thinning in the fovea, inner ring, and outer ring. Effect estimates are displayed in these three macular regions showing the largest effect on the outer ring −0.88 (CI −1.12, −0.65, P = .000), followed by the inner ring (−0.77 [CI −0.96, −0.59] P = .000) and fovea (−0.37 [CI −0.65, −0.09], P = .010) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Total macular thickness in AD and HC. Forest plots of standardized mean macular thickness, in the (A) fovea, (B) outer ring, and (C) inner ring. (D) Shows the ETDRS regions of the macula (inner and outer ring subdivided in four quadrants). Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; HC, healthy control.

3.3. Meta-regression

Meta-regression shows that OCT type, mean study MMSE score, glaucoma exclusion score, and mean study age are not associated with the SMD in the AD group compared to HC.

3.4. Publication bias

The funnel plot is relatively asymmetrical and indicates publication bias (Supplementary Fig. 1).

4. Discussion

We performed a systematic review and comprehensive meta-analysis to assess differences in retinal layer thickness between AD and MCI patients and HCs. We show that both mean peripapillary RNFL and macular thickness decreased in AD patients compared to HCs. The difference in thickness is more apparent with TD scanners than the now widely used SD-OCT. This presents an interesting finding because the resolution (5 μm vs. 10 μm) and acquisition time of the currently used SD-OCT are superior to TD-OCT and currently used by most clinicians. However, fewer artifacts and significantly higher retinal thickness in SD-OCT with higher resolution compared to TD-OCT were reported before, and this may be an explanation for these differences [34].

The MCI group was in between AD and HC. As the differences are small, however, application of retinal thickness measurements as a diagnostic biomarker in the individual patient is challenging.

We found peripapillary RNFL thickness to be lower in the superior and inferior quadrants than in nasal and temporal quadrants. This may be related to the fact that the superior and inferior quadrants contain more neurons, and therefore, neurodegeneration is expected to be most prominent. Similarly, we would expect a more prominent change in the thicker GCL in the inner ring of the macula. In contrast, macular thickness displays the most prominent decrease in the outer ring, which may reflect RNFL loss in the periphery.

Retinal thinning is associated not only with AD but also with glaucoma. Glaucoma is a chronic, age-related, and neurodegenerative disease affecting the RNFL and hypothesized to share a common pathophysiology (neuroinflammation, lower Aβ in CSF [35] and vitreous humor [36], and retinal ganglion cell death [37]). In addition, the prevalence of glaucoma is increased in AD patients; 25.9 %, compared to 1%–5.2% in the normal population [38], [39], [40]. The reverse correlation is less distinct as some population studies of glaucoma patients show a higher risk of AD [41], whereas others reported no association [42], [43]. Possibly, AD is a risk factor for glaucoma, or AD and glaucoma share a pathophysiological process with retinal neurodegeneration as final common pathway. Two recent studies of Eraslan et al. and Cesareo et al., measuring RNFL with OCT, visual field defects with frequency doubling technology, and optic nerve head morphology with HRT, showed similar patterns of RNFL thinning, visual field loss, and optic nerve head morphology in AD and normal tension glaucoma [10], [44]. Consequently, it seems very challenging to discriminate retinal changes due to AD from retinal changes due to glaucoma. Therefore, stressing the need to account for glaucoma as a contributor to retinal thickness decreases.

The strengths of our meta-analysis are the inclusion of a large number of AD and MCI patient cohorts and HCs, as well as assessment of both peripapillary and macular thinning. In addition, we addressed scanner difference and the influence of glaucoma as a possible confounder.

Among limitations are the studies used showed heterogeneity in the meta-regression that could not be attributed to scanner type, MMSE, and/or age. Another limitation is that AD diagnosis in the included studies was based on clinical criteria without the support of biomarkers. The National Institute on Ageing–Alzheimer's Association (NIA-AA) criteria suggest incorporating the use of biomarkers reflecting AD pathology for an accurate diagnosis [2]. In this respect, it is important to realize that several amyloid PET studies showed that around 20% of clinically diagnosed AD patients have a normal amyloid PET scan, leading to a change in clinical diagnosis [45]. A third limitation is that we did not have sufficient data to compare retinal thickness in other neurodegenerative diseases. We found only one study with data on PD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), showing retinal thinning in PD and DLB. A fourth limitation is revealed by the funnel plot asymmetry and statistical tests, indicating publication bias, with an overrepresentation of smaller positive studies. Study results may thus be an overestimation of the true effect.

Segmentation software recently became available to section retinal layers for assessment of change in individual retinal layers. With this method, a loss of GCL was demonstrated in patients with diabetes mellitus type II for example, without signs of vasculopathy, in the inner ring, reflecting neuroretinal degeneration [46]. A recent study of Salobrar-Garcia et al. used segmentation analysis in AD and mainly showed a contribution of inner retinal layers, GCL, RNFL, and inner plexiform layer (IPL) [9]. Interestingly, they found a decrease in macular thickness while peripapillary thickness was unchanged, suggesting macular before peripapillary degeneration. In contrast, an increase of IPL thickness was reported in a recent study of Snyder et al. in preclinical AD [47]. Future research may use segmentation to identify the alterations of specific retinal layers in AD and its preclinical and prodromal stages.

As shown before and in this meta-analysis, group differences in RNFL and macular thickness are small, limiting clinical application as a biomarker. When comparing these group differences with widely used MRI biomarkers, however, retinal neurodegeneration shows a comparable group difference to visual rating scores such as medial temporal lobe atrophy (1.1–1.79 SD) [48], [49], [50]. To assess the diagnostic value of OCT, comparison with the current gold standard, NIA-AA criteria–based diagnosis with the use of biomarkers (e.g., amyloid PET, CSF, and/or FDG-PET) is necessary to determine sensitivity and specificity of OCT.

5. Conclusion

We found that the peripapillary RNFL and macular thickness are significantly decreased in AD patients compared to HC. In addition, we took glaucoma into account as a potential confounder, that possibly overestimated the effect of AD on retinal thickness in the described studies. As of yet OCT cannot yet be applied as a diagnostic biomarker for AD in clinical practice.

Future research should focus on OCT measurements in a well-described cohort of preclinical, prodromal (i.e., MCI) and demented AD patients and subjects with information on amyloid status (positive or negative). Segmentation of individual retinal layers may provide insight into the pathophysiology of retinal neurodegeneration in AD. Correlating OCT measurements with other biomarkers of neuronal injury (i.e., hippocampal atrophy on MRI, hypometabolism on FDG-PET, or increased CSF tau and pTau levels) may give new insight in OCT measurements as biomarker of neurodegeneration.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: The use of optical coherence tomography (OCT) to asses retinal layer thickness has expanded from ophthalmology to neurodegenerative diseases, in specific Alzheimer's disease. The authors reviewed the literature for studies performing OCT in AD patients, MCI patients and controls and no meta-analysis inclusive of all the studies has been considered.

-

2.

Interpretation: Our meta-analysis shows that retinal neurodegeneration is present in AD and MCI patients and might therefore mirror brain pathology. However, changes are small, which might hamper use as a diagnostic biomarker.

-

3.

Future direction: Studies assessing OCT measurements together with neuropsychological assessment, MRI, CSF, and PET biomarkers should be conducted to assess its role as a diagnostic biomarker. In addition, more specific retinal biomarkers (e.g., retinal amyloid) might aid early noninvasive diagnosis and disease monitoring before severe neurodegeneration is present.

Acknowledgments

F.D.V., P.J.V., F.H.B., and corresponding author J.d.H. report no disclosures. This study is not industry sponsored. J.d.H. contributed to the study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation. F.D.V. contributed to the critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. P.J.V. contributed to the critical revision of the article for important intellectual content and interpretation. F.H.B. contributed to the critical revision of the article for important intellectual content and study supervision.

Footnotes

J.d.H. performed statistical analysis.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2016.12.014.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Funnel plot.

References

- 1.Sperling R.A., Aisen P.S., Beckett L.A., Bennett D.A., Craft S., Fagan A.M. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Kawas C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jack C.R., Holtzman D.M. Biomarker modeling of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2013;80:1347–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reardon S. Antibody drugs for Alzheimer's show glimmers of promise. Nature. 2015;523:509–510. doi: 10.1038/nature.2015.18031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petzold A., de Boer J.F., Schippling S., Vermersch P., Kardon R., Green A. Optical coherence tomography in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:921–932. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70168-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu J.G., Feng Y.F., Xiang Y., Huang J.H., Savini G., Parisi V. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness changes in Parkinson disease: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pillai J.A., Bermel R., Bonner-Jackson A., Rae-Grant A., Fernandez H., Bena J. Retinal nerve fiber layer thinning in Alzheimer's disease: a case-control study in comparison to normal aging, Parkinson's disease, and non-Alzheimer's dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31:430–436. doi: 10.1177/1533317515628053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.La Morgia C., Ross-Cisneros F.N., Koronyo Y., Hannibal J., Gallassi R., Cantalupo G. Melanopsin retinal ganglion cell loss in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:90–109. doi: 10.1002/ana.24548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salobrar-Garcia E., Hoyas I., Leal M., de Hoz R., Rojas B., Ramirez A.I. Analysis of retinal peripapillary segmentation in early Alzheimer's disease patients. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:636548. doi: 10.1155/2015/636548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eraslan M., Çerman E., Çekiç O., Balci S., Dericioğlu V., Sahin Ö. Neurodegeneration in ocular and central nervous systems: optical coherence tomography study in normal-tension glaucoma and Alzheimer disease. Turk J Med Sci. 2015;45:1106–1114. doi: 10.3906/sag-1406-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Güneş A., Demirci S., Tök L., Tök Ö., Demirci S. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in Alzheimer disease using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Turk J Med Sci. 2015;45:1094–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu D., Zhang L., Li Z., Zhang X., Wu Y., Yang H. Thinner changes of the retinal nerve fiber layer in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0268-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oktem E.O., Derle E., Kibaroglu S., Oktem C., Akkoyun I., Can U. The relationship between the degree of cognitive impairment and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:1141–1146. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-2055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung C.Y., Ong Y.T., Hilal S., Ikram M.K., Low S., Ong Y.L. Retinal ganglion cell analysis using high-definition optical coherence tomography in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45:45–56. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao L., Liu Y., Li X., Bai Q., Liu P. Abnormal retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and macula lutea in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bambo M.P., Garcia-Martin E., Gutierrez-Ruiz F., Pinilla J., Perez-Olivan S., Larrosa J.M. Analysis of optic disc color changes in Alzheimer's disease: a potential new biomarker. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;132:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larrosa J.M., Garcia-Martin E., Bambo M.P., Pinilla J., Polo V., Otin S. Potential new diagnostic tool for Alzheimer's disease using a linear discriminant function for Fourier domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:3043–3051. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ascaso F.J., Cruz N., Modrego P.J., Lopez-Anton R., Santabarbara J., Pascual L.F. Retinal alterations in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: an optical coherence tomography study. J Neurol. 2014;261:1522–1530. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7374-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polo V., Garcia-Martin E., Bambo M.P., Pinilla J., Larrosa J.M., Satue M. Reliability and validity of Cirrus and Spectralis optical coherence tomography for detecting retinal atrophy in Alzheimer's disease. Eye (Lond) 2014;28:680–690. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gharbiya M., Trebbastoni A., Parisi F., Manganiello S., Cruciani F., D'Antonio F. Choroidal thinning as a new finding in Alzheimer's Disease: Evidence from enhanced depth imaging spectral domain optical coherence tomography. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:907–917. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kromer R., Serbecic N., Hausner L., Froelich L., Aboul-Enein F., Beutelspacher S.C. Detection of retinal nerve fiber layer defects in Alzheimer's disease using SD-OCT. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:22. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno-Ramos T., Benito-Leon J., Villarejo A., Bermejo-Pareja F. Retinal nerve fiber layer thinning in dementia associated with Parkinson's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34:659–664. doi: 10.3233/JAD-121975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marziani E., Pomati S., Ramolfo P., Cigada M., Giani A., Mariani C. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell layer thickness in Alzheimer's disease using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:5953–5958. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirbas S., Turkyilmaz K., Anlar O., Tufekci A., Durmus M. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in patients with Alzheimer disease. J Neuroophthalmol. 2013;33:58–61. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e318267fd5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moschos M.M., Markopoulos I., Chatziralli I., Rouvas A., Papageorgiou S.G., Ladas I. Structural and functional impairment of the retina and optic nerve in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:782–788. doi: 10.2174/156720512802455340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kesler A., Vakhapova V., Korczyn A.D., Naftaliev E., Neudorfer M. Retinal thickness in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011;113:523–526. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Y., Li Z., Zhang X., Ming B., Jia J., Wang R. Retinal nerve fiber layer structure abnormalities in early Alzheimer's disease: evidence in optical coherence tomography. Neurosci Lett. 2010;480:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paquet C., Boissonnot M., Roger F., Dighiero P., Gil R., Hugon J. Abnormal retinal thickness in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;420:97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berisha F., Feke G.T., Trempe C.L., McMeel J.W., Schepens C.L. Retinal abnormalities in early Alzheimer's disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2285–2289. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iseri P.K., Altinas O., Tokay T., Yuksel N. Relationship between cognitive impairment and retinal morphological and visual functional abnormalities in Alzheimer disease. J Neuroophthalmol. 2006;26:18–24. doi: 10.1097/01.wno.0000204645.56873.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parisi V., Restuccia R., Fattapposta F., Mina C., Bucci M.G., Pierelli F. Morphological and functional retinal impairment in Alzheimer's disease patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1860–1867. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wan X., Wang W., Liu J., Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whiting P., Rutjes A.W., Reitsma J.B., Bossuyt P.M., Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forte R., Cennamo G.L., Finelli M.L., de Crecchio G. Comparison of time domain Stratus OCT and spectral domain SLO/OCT for assessment of macular thickness and volume. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:2071–2078. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouwman F.H., Schoonenboom N.S., Verwey N.A., van Elk E.J., Kok A., Blankenstein M.A. CSF biomarker levels in early and late onset Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1895–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoneda S., Hara H., Hirata A., Fukushima M., Inomata Y., Tanihara H. Vitreous fluid levels of beta-amyloid((1-42)) and tau in patients with retinal diseases. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005;49:106–108. doi: 10.1007/s10384-004-0156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sadun A.A., Bassi C.J. Optic nerve damage in Alzheimer's disease. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32621-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Voogd S., Ikram M.K., Wolfs R.C., Jansonius N.M., Hofman A., de Jong P.T. Incidence of open-angle glaucoma in a general elderly population: the Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1487–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfs R.C., Borger P.H., Ramrattan R.S., Klaver C.C., Hulsman C.A., Hofman A. Changing views on open-angle glaucoma: definitions and prevalences—The Rotterdam Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3309–3321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bayer A.U., Ferrari F., Erb C. High occurrence rate of glaucoma among patients with Alzheimer's disease. Eur Neurol. 2002;47:165–168. doi: 10.1159/000047976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin I.C., Wang Y.H., Wang T.J., Wang I.J., Shen Y.D., Chi N.F. Glaucoma, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease: an 8-year population-based follow-up study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ou Y., Grossman D.S., Lee P.P., Sloan F.A. Glaucoma, Alzheimer disease and other dementia: a longitudinal analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19:285–292. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2011.649228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keenan T.D., Goldacre R., Goldacre M.J. Associations between primary open angle glaucoma, Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia: record linkage study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:524–527. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cesareo M., Martucci A., Ciuffoletti E., Mancino R., Cerulli A., Sorge R.P. Association between Alzheimer's disease and glaucoma: a study based on Heidelberg retinal tomography and frequency doubling technology perimetry. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:479. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ossenkoppele R., Jansen W.J., Rabinovici G.D., Knol D.L., van der Flier W.M., van Berckel B.N. Prevalence of amyloid PET positivity in dementia syndromes: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:1939–1949. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Dijk H.W., Verbraak F.D., Kok P.H., Stehouwer M., Garvin M.K., Sonka M. Early neurodegeneration in the retina of type 2 diabetic patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2715–2719. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Snyder P.J., Johnson L.N., Lim Y.Y., Santos C.Y., Alber J., Maruff P. Nonvascular retinal imaging markers of preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2016;4:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lehmann M., Koedam E.L., Barnes J., Bartlett J.W., Barkhof F., Wattjes M.P. Visual ratings of atrophy in MCI: prediction of conversion and relationship with CSF biomarkers. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clerx L., Visser P.J., Verhey F., Aalten P. New MRI markers for Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging and a comparison with medial temporal lobe measurements. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29:405–429. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van de Pol L.A., Hensel A., van der Flier W.M., Visser P.J., Pijnenburg Y.A., Barkhof F. Hippocampal atrophy on MRI in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:439–442. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.075341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.