Abstract

Smoking prevalence among LGBTQ + youth and young adults is alarmingly high compared to their non-LGBTQ + peers. The purpose of the scoping review was to assess the current state of smoking prevention and cessation intervention research for LGBTQ + youth and young adults, identify and describe these interventions and their effectiveness, and identify gaps in both practice and research.

A search for published literature was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, PsychInfo, and LGBT Life, as well as an in-depth search of the grey literature. All English articles published or written between January 2000 and February 2016 were extracted.

The search identified 24 records, of which 21 were included; 11 from peer reviewed sources and 10 from the grey literature. Of these 21, only one study targeted young adults and only one study had smoking prevention as an objective. Records were extracted into evidence tables using a modified PICO framework and a narrative synthesis was conducted. The evidence to date is drawn from methodologically weak studies; however, group cessation counselling demonstrates high quit rates and community-based programs have been implemented, although very little evidence of outcomes exist. Better-controlled research studies are needed and limited evidence exists to guide implementation of interventions for LGBTQ + youth and young adults.

This scoping review identified a large research gap in the area of prevention and cessation interventions for LGBTQ youth and young adults. There is a need for effective, community-informed, and engaged interventions specific to LGBTQ + youth and young adults for the prevention and cessation of tobacco.

Keywords: LGBTQ, Tobacco use, Smoking cessation, Interventions, Youth, Young adults, Review

Highlights

-

•

We conducted a scoping review on cessation programs for LGBTQ + young adults.

-

•

A large research gap in the area of tobacco control for LGBTQ + young adults exists.

-

•

Tobacco control interventions specific to LGBTQ + youth and young adults are needed.

1. Introduction

Smoking prevalence among lesbian, gay, bisexuals, transgender, queer, and other sexual and gender minority (LGBTQ +) youth and young adults (YYA) in Canada is alarmingly high and there is great disparity when compared to the non-LGBTQ + population. Estimates of daily smoking prevalence among LGBTQ + adults range between 33% to 45%; compared to an average of 18.9% for non-LGBTQ + adults (Clarke and Coughlin, 2012). Prevalence rates are higher among LGBTQ + YYA (Clarke and Coughlin, 2012). According to the 2013–2014 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), in 18 to 24 year olds, 34.0% of homosexuals1 and 35.1% of bisexuals report smoking daily or occasionally compared to 23.3% of heterosexuals (Health Statistics Division, Statistics Canada, 2015.). Further, 22% of high school aged adolescents who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual report daily cigarette use compared to 11% of non-LGB persons (Azagba et al., 2014).

Although reasons behind high LGBTQ + smoking rates are not completely understood, several reasons have been suggested that contribute to high smoking rates among LGBTQ +. Blosnich et al. (2013) reviewed epidemiologic studies and other authors have also identified the following factors contributing to tobacco use: minority stress (refers to chronically high levels of stress faced by members of stigmatized minority groups) and discrimination (Blosnich et al., 2013, Gamarel et al., 2016, Newcomb et al., 2014, Remafedi, 2007, Youatt et al., 2015), victimization (Blosnich et al., 2013, Newcomb et al., 2014, Remafedi, 2007, Youatt et al., 2015), harassment (Blosnich et al., 2013), abuse (Blosnich et al., 2013, Remafedi, 2007), mental health (Blosnich et al., 2013, Newcomb et al., 2014), targeted marketing by the tobacco industry (Blosnich et al., 2013, Remafedi, 2007, Youatt et al., 2015), frequenting bars and nightclubs (Blosnich et al., 2013, Remafedi, 2007, Youatt et al., 2015), other substance use (Remafedi, 2007), and higher rates of personal stress (Newcomb et al., 2014, Remafedi, 2007, Youatt et al., 2015), depression (Blosnich et al., 2013, Gamarel et al., 2016, Newcomb et al., 2014), alcohol use (Blosnich et al., 2013, Gamarel et al., 2016, Remafedi, 2007), and low socioeconomic status (Blosnich et al., 2013).

Remafedi (2007) conducted a qualitative study on tobacco use among LGBT youth and determined that because of factors unique to LGBT youth (e.g., sexuality-related stress), culturally specific approaches to tobacco use prevention and cessation are required. In a study by Remafedi and Carol (2005), LGBT youth highlighted that LGBT should be directly involved in program planning and implementation, and programs should be tailored to be culturally specific. A number of prevention and cessation interventions have been developed and implemented that either target those in the LGBTQ + community or are general population interventions that are applied to this community. The majority of the published research is related to group cessation counselling (GCC) interventions tailored for LGBTQ + smokers (e.g., The Last Drag, Stop Dragging Your Butt, Queer Quit, etc.) (Dickson-Spillmann et al., 2014, Doolan and Froelicher, 2006, Eliason et al., 2012, Program Training and Consultation Centre, 2005, Walls and Wisneski, 2010).

In a review conducted by Lee and colleagues (Lee et al., 2014), the authors found that GCC programs tailored for members of the LGBT community exist, but these programs have limited reach. It was suggested that non-tailored treatments may work for both LGBT and non-LGBT persons (Lee et al., 2014). The review stated the need for research to identify whether community-desired, tailored interventions improve cessation outcomes. Research to date on non-tailored treatments is limited in terms of generalizability as the studies were set in urban areas with large LGBT populations. Lee and colleagues (Lee et al., 2014) also recommend investigation of inter-group differences (e.g., lesbian versus bisexual and racial/ethnic LGBTQ + minorities), and the need for research on the impact of policy-based interventions (e.g., taxation and smoke-free spaces) on reducing disparity and LGBTQ + tobacco use cessation. Burkhalter (2015) suggests that in regions or communities where LGBTQ + persons are more stigmatized, LGBTQ + tailored interventions could be more effective because they assure a safe, validating environment that enhances receptivity to cessation (Berger and Mooney-Somers, 2016). The amount a program needs to be tailored to reach the community and impact tobacco use is largely unknown.

A scoping review aims to “map the literature on a particular topic or research area and provide an opportunity to identify key concepts; gaps in the research; and types and sources of evidence to inform practice, policymaking, and research” (Daudt et al., 2013). A scoping review was conducted over a systematic review primarily because the research question was broad and there was a need to identify parameters and gaps in this body of literature (Armstrong et al., 2011). Scoping reviews are commonly performed to examine the extent, range, and nature of research activity in a topic area (Pham et al., 2014). The purpose of this scoping review was to: assess the current state of intervention research for LGBTQ +, specifically for YYA (aged 16 to 29), as no review of this specific target population and young age group has ever been conducted. While there have been other recently published reviews (Lee et al., 2014, Burkhalter, 2015), this review contributes something new to the field, as no reviews have focused on the youth and young adult population. The scoping review was conducted to identify and describe what is known about interventions targeted specifically for the YYA population and their effectiveness, and identify gaps in both practice and research on LGBTQ + tobacco use reduction and cessation. The paucity of evidence for LGBTQ + YYA is an important issue and, thus, was the original focus of this review. The scoping review was part of a larger study to identify preferred, evidence-based tobacco use prevention and cessation interventions for LGBTQ + YYA.

2. Methods

We conducted a scoping review of the literature, using the framework by Arksey and O'Malley (2005). Arksey and O'Malley (2005) highlight four objectives for conducting scoping reviews: 1) to examine the extent, range, and nature of research activity; 2) to determine the value of undertaking a full systematic review; 3) to summarize and disseminate research findings; and 4) to identify research gaps in the literature. Our scoping review aligned to all four objectives.

In the first step, we finalized the objectives for the scoping review in consultation with knowledge users including partners from Rainbow Health Ontario (a community-based health service organization that serves the LGBTQ community) and other co-investigators. Together, the team determined the appropriate keyword search terms and made the decision to search the grey literature as well as identifying specific grey literature sources.

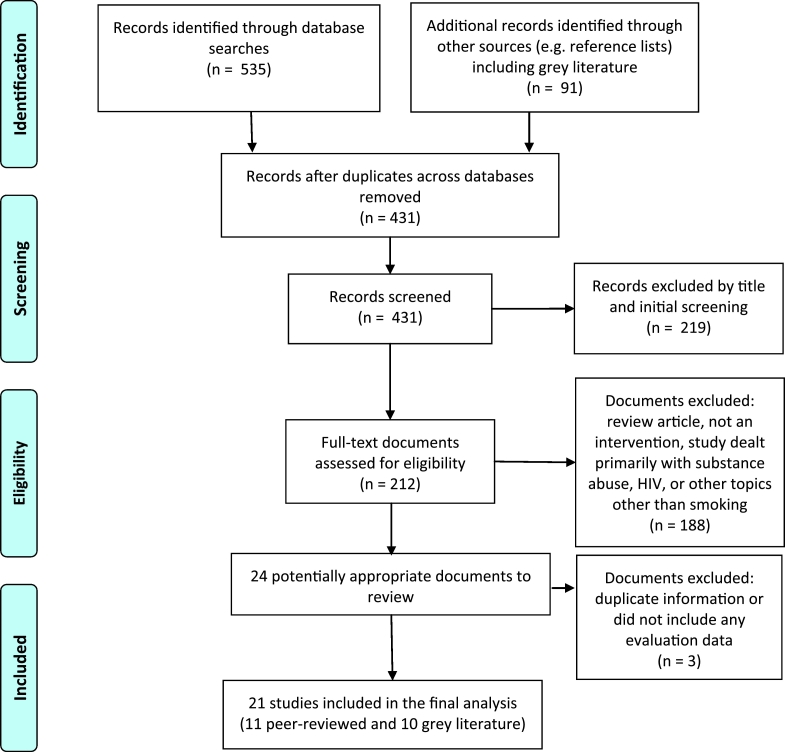

In step two, the team identified studies and selected those to be included for review. Building upon existing reviews, we identified sources of information by comprehensively gathering and mapping publications and grey literature. An information specialist searched the published literature in PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, PsychInfo, and LGBT Life using an extensive keyword search with the following terms: (‘smoking’ or ‘tobacco use’ or ‘nicotine’ or ‘cigarette*’) and (‘lesbian’ or ‘gay’ or ‘homosexual’ or ‘bisexual’ or ‘transgender*’ or ‘queer’ or ‘sexual minorit*’ or ‘two-spirit*’ or ‘LGBT*’) and (‘adolescen*’ or ‘youth’ or ‘young adult’ or ‘teen*’). Youth was defined as < 18 years of age and young adult was defined as 18 to 29 years of age. All English articles published in the last 16 years, between 2000 and February 2016 were included (n = 546). Articles older than this were deemed too out-of-date. Reference lists of each published article were scanned to identify additional sources (n = 25). To identify the grey literature, we used keywords and focused search string queries with Google, Duck Duck Go, and Bing search engines, as well as reaching out to LGBTQ + health specialists in North America (e.g., Rainbow Health Ontario and the Truth Initiative). Selected websites were identified and searched (e.g., National LGBT Tobacco Control Network). Grey literature resources were also found in citation lists of both the peer-reviewed and grey literature. Searching these sources yielded 66 grey literature documents. A total of 351 articles were identified for screening after duplicates across the databases and sources searched were removed (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of identification of relevant studies.

For step three, two independent reviewers (AA, AS) examined the titles and abstracts and content of the grey literature to determine relevance to the scoping review objectives; a third member arbitrated as needed (KW). In this stage, the research team discussed the results of the literature search. We found that the literature did not include many programs targeting YYA specifically, but were for all LGBTQ + persons older than 18 years of age. As such, to be included, the literature had to focus on interventions or programs targeting any LGBTQ + persons that included either a description of the implementation of the program and/or its evaluation. This refined the purpose of our scoping review by eliminating the age restrictions when assessing the current state of intervention research for LGBTQ + persons, resulting in 156 eligible documents for review (see Fig. 1). Articles not relevant to the objectives were excluded when: they did not focus on LGBTQ + persons primarily and/or were not a smoking cessation intervention/program; reported on attitudes, preferences or intentions about cessation or antecedents for and prevalence of smoking in the population; or the primary focus of the study was on other health issues (i.e., mental health, sexual behaviour, HIV/AIDS). Three articles were excluded from the review because they were literature reviews (Blosnich et al., 2013, Doolan and Froelicher, 2006, Lee et al., 2014), but their reference lists were perused to check for additional citations.

In step four, key items from the documents were charted according to a modified PICO framework (Population, Intervention/Exposure, Comparison, Outcome) (Richardson et al., 1995). The following information was extracted by one reviewer (DD) and inputted into an Excel spreadsheet: authors, year of publication, target population (Lesbian, men who have sex with men [MSM], LGBT, etc.), intervention, comparison group(s), primary outcomes, year of program implementation, study location, methodology used, characteristics of the sample and the program, outcomes related to the program, theoretical framework for intervention design, and if the program was tailored to LGBTQ + persons. A second independent reviewer (NB) conducted a repeat extraction of all the documents for verification purposes. Interrater reliability between the 2 reviewers was assessed to be very strong with 90% agreement, and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus between the 2 reviewers.

In the final step the research team discussed the extraction chart and decided on the broad themes by which to present results. Results were collated, summarized, and reported by intervention type, methods used, presence of a theoretical framework, etc. In the tradition of scoping reviews (Davis et al., 2009, Levac et al., 2010), the team did not conduct a quality assessment of the included studies. As described by Arksey and O'Malley (2005), we provide basic numerical summaries and interpretive synthesis from the data extracted. First, we summarize the studies and their characteristics, and then we narratively describe the types of interventions for the LGBTQ + community.

3. Results

3.1. Document retrieval and publication range

After reviewing all eligible documents, we identified 24 documents reporting interventions for smoking cessation/reduction in LGBTQ + persons (see Fig. 1). Of these, three articles were excluded because they provided duplicate information and/or did not include program outcomes or evaluation data (Gentium Consulting, 2005, Howard Brown, n.d, Walls, 2008). In total, 21 documents were included that provided details for 19 distinct interventions. Of these, 11 documents were peer-reviewed articles and 10 were grey literature. One article reported results from three interventions (Matthews et al., 2013a), another document reported results from two campaigns (Legacy, 2012), and other documents provided information on varying aspects of the same intervention and thus, results were grouped by intervention (see Table 1). The year of publication ranged from 2002 to 2015, with the majority (86%) published from 2005 onwards.

Table 1.

Published and grey literature documenting LGBTQ + tobacco interventions.

| Authors | Design | Intervention | Sample | Outcomes | Target audience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome evaluation: cessation (validated) | |||||

| Harding et al., 2004 | Quasi-experimental one group pre-post test design | National Health Service approved program (London, UK): Seven-week program at a community-based volunteer led charity. | Gay men, adults aged 23–63 years | 45% quit rate (ITT) confirmed via CO at seventh session. | G |

| Dickson-Spillmann et al., 2014 | Quasi-experimental one group pre-post test design | Queer Quit (Zurich, Switzerland): Seven-week group cessation program. Based on the study by Harding et al. (2004). | Gay men, adults mean age = 42.96 years |

65.7% quit rate (ITT) at seventh session verified by CO and 28.6% quit rate (ITT) at the 6-month follow-up. | G |

| Grady et al., 2014 | Quasi-experimental one group pre-post test design, based on two RCTs | Two non-tailored RCTs (San Francisco, USA): Twelve-week treatment with group counselling, NRT, bupropion, and randomized extended treatment. Extended treatment continued until week 52 and included control, or combinations of counselling and/or pharmacotherapy. | LGBT N = 136, adults mean age = 45.77 years 68% G, 19% B, 10% L, 4% T non-LGBT N = 641, adults mean age = 49.32 years |

38% (sexual and gender minorities) vs. 40% (heterosexuals) quit rate (ITT) at week 104 (no significant difference). Confirmed via CO testing. | No |

| Covey et al., 2009 | Quasi-experimental one group pre-post test design, based on a RCT | One non-tailored RCT (NY, USA): Eight-week treatment phase with individual counselling, NRT, and/or pharmacotherapy. | 54 GB males adults mean age for GB = 37.7 243 heterosexual men |

Gay/bisexual had high quit rates in the early weeks, but rates converged by end of treatment; 59% GB vs. 57% heterosexual males quit rate. Verified by CO. |

No |

| Outcome evaluation: cessation (self-report) | |||||

| Eliason et al., 2012 | Quasi-experimental one group pre-post test design | The Last Drag (San Francisco, USA): Six-week, seven session group cessation program based on the transtheoretical model and offered at a LGBT community center. |

N = 326, aged 21–78 years 90% LG, 6% B, 4% H, < 1% T |

59% had quit (ITT) at the final session; 36% had quit (ITT) at the 6-month follow-up (self-report data) | LGBT |

| Walls and Wisneski, 2010 | Quasi-experimental one group pre-post test design | The Last Drag (Colorado, USA): Six-week, seven session group cessation program offered by five LGBT community-based organizations in three Colorado cities. |

N = 44, aged 18–62 years 36% G, 27% L, 14% B, 11% H, 7% Q, 2% T |

73% self-reported that they quit at the final session. | LGBT |

| University of California San Francisco AIDS Research Instit, University of California, 2002 | Qualitative Program Evaluation | QueerTIPS (San Francisco, USA): eight-week, nine session group cessation program with two booster sessions at a later date in the community. |

N = 18, adults mean age = 37 years LGBT |

40% self-reported quitting by the last session | LGBT |

| Matthews et al., 2013a | Quasi-experimental one group pre-post test design | Project Exhale, based on cognitive behavioural therapy, motivational interviewing and 12-step, addictions but culturally adapted (Chicago, USA): Six-week, seven session group cessation program at a community-based health and research center. |

N = 31, adults mean age = 46 years men who have sex with men (MSM), African American, HIV + |

24% quit rate at 1-month and 16% (ITT); 10% quit rate at 3-months and 6% (ITT) | MSM who are African American and HIV + |

| Outcome (self-report) and process evaluation | |||||

| Matthews et al., 2013b | Quasi-experimental one group pre-post test design | Call It Quits (Chicago, USA): Eight-session group cessation program offered in 15 groups at a LGBT community health centre. |

N = 105, adults 18–65 years 76.9% homosexual, 14.4% other, 8.7% bisexual, 5.8% T |

52% of participants completed ≥ 75% of sessions; 39% quit rate (ITT) at 1-month post-quit date |

LGBT |

| Matthews et al., 2013b | Quasi-experimental one group pre-post test design | Put It Out (Chicago, USA): Six-session group cessation program offered in 10 groups at a LGBT community health centre. NRT was offered for free. |

N = 60, adults 18–65 years 75.0% homosexual, 11.7% other, 13.3% bisexual, 0% T |

32% of participants completed ≥ 75% of sessions; 23% quit rate (ITT) at 1-month post-quit date |

LGBT |

| Matthews et al., 2013b, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2013, Barry, 2012 | Quasi-experimental one group pre-post test design; Qualitative Program Evaluation | Bitch to Quit (Chicago, USA): Eight-session group cessation program offered in 5 groups at a LGBT community health centre. |

N = 33, adults 18–65 years 71.9% homosexual, 15.6% other, 12.5% bisexual, 6.1% T |

55% of participants completed ≥ 75% of sessions; 27% quit rate (ITT) at 1-month post-quit date |

LGBT |

| Fallin et al., 2015, Legacy, 2012 | Post cross-sectional surveys one-year apart; Quantitative Program Evaluation | CRUSH (Las Vegas, USA): Marketing campaign with media and events targeting LGBT bar/club going young adults. Brand ambassadors promoted the CRUSH brand (“cute, fresh, and smokefree” and “partying fresh and smokefree”) with live performances, DJs, dancers, models, games and other interactive activities and texted users to receive a text messaging cessation program. |

N = 2395 79% identified as LGBT adults 21–30 years |

104 nightclub events were held that reached 20,000 persons; 25,000 website visits with 100,000 page views. The brand had 4500 Facebook friends, 500,000 YouTube video views, and 1300 YouTube subscribers. Over 2000 individuals signed up for the text messaging cessation program. 53% of respondents reported exposure to CRUSH and of those exposed, 60.8% reported they liked/really liked the campaign and 86.3% of respondents understood the campaign message. For those involved in the cross-sectional survey, tobacco use dropped from 47% to 39.6% after one year. Overall, smoking rates in southern Nevada fell from 63% (2005) to 47% (2008) and the local helpline received 1411 calls from LGBT (2008–2010). | LGBT |

| Program Training and Consultation Centre (PTCC), 2005 | Quantitative and Qualitative Program Evaluation | Stop Dragging Your Butt (Ottawa, Canada): Based on social cognitive theory and transtheoretical model, five smoking cessation groups with eight sessions of group counselling occurred in English and French with one follow-up session, if needed. The program was delivered at an LGBT resource centre. |

N = 48, adults 22–72 years LGBT |

Of the 20 individuals reaching the final session, 45% quit completely (self-report); 85% rated the overall program as excellent; 85% felt the program was very useful when tailored. | LGBT |

| Process evaluation only | |||||

| Aragon, 2006, Aragon and Le Veque, 2006 | Quantitative Program Evaluation | The Last Drag (Los Angeles, USA): Three-month communication campaign (“Breath Easier. Play Harder”) with print ads, internet presence, gay anti-smoking street team for peer-to-peer outreach in bars and nightclub, and media relations. | LGBT | Website averaged 1986 hits/day in the first month, 500,000 print impressions, the 35 blogs discussed campaign (99% positive) and they had national media coverage. | LGBT |

| Huber et al., 2012 | Quasi-experimental pre-post test design, long-term observation study | CTQ (Zurich, Switzerland): HIV care physicians were given structured training based on the transtheoretical model to assess, counsel for smoking cessation, and to provide information on pharmacotherapy to all patients at university clinics and health centers. Physicians arranged for a follow-up appointment and assessed motivation for quitting. | 1689 participants in 6068 clinic visits of which 46% were smokers adults 33–44 years 45% with MSM |

Counselling was carried out in 1888 of 2374 visits (80%) for current smokers. Training physicians increased smoking cessation but there were no significant differences between the MSM group and heterosexuals. | No |

| National LGBT Tobacco Control Network, 2008 | Qualitative Program Evaluation | Call It Quits (CIQ; Minnesota, USA): Quit line counsellors were provided in-person training to provide culturally tailored counselling to LGBT callers. | Counsellors from all Minnesota quit lines | 20 trainings were conducted; community support for program was evident. | LGBT |

| National LGBT Tobacco Control Network, 2010 | Qualitative Program Evaluation | LGBT SmokeFree Project (previously Becoming Smoke Free with Pride; NY; USA) based on transtheoretical model; One targeted three-hour workshop (Not Quite Ready to Quit, NQR2Q) was provided to those thinking about quitting, and six counselling sessions (Commit To Quit) were offered to those in preparation/action stages at a LGBT community centre. | LGBT | Smokers kept coming back due to positive group experience and because a trusted center was used. Many attendees returned the incentive in gratitude for quitting. Motivation to quit increased significantly and quitting self-efficacy increased. 82% felt an LGBT-specific program was important. | LGBT, HIV + |

| Legacy, 2012 | Qualitative Program Evaluation | Delicious Lesbian Kisses (DLK; USA): social marketing campaign across the country with ads, written articles, posters, postcards, and promotional items that were distributed and available at LGBT venues where “kiss-ins” were held at clubs, followed by information about cessation from volunteers. | Lesbians women who partner with women (WPW) adults > 40 years' old |

Women seeking cessation services in Washington increased by 100%. Postcards and wristbands still around in 2012, seven years after end of campaign. | L, WPW |

| Matthews et al., 2014 | Prospective two group RCT | Courage to Quit (CTQ) vs. CTQ – Culturally Tailored (Chicago, USA) based on the transtheoretical model and the health belief model. Six-week group cessation program conducted at community and faith centers, and clinical and academic settings. | Intended sample size = 400 LGBT, adults 18–65 years |

Authors hypothesize that quit rates will be higher in the CTQ – Culturally Tailored group vs. the non-tailored program. | LGBT |

3.2. Study designs

Of the 21 documents included in this review, the majority were quasi-experimental designs (n = 9) with no comparison group (Dickson-Spillmann et al., 2014, Eliason et al., 2012, Walls and Wisneski, 2010, Matthews et al., 2013a, Covey et al., 2009, Grady et al., 2014, Harding et al., 2004, Huber et al., 2012, Matthews et al., 2013b); six provided descriptive qualitative program evaluation data (Barry, 2012, Senseman, 2008, University of California, 2002, University of California San Francisco AIDS Research Instit, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2013, Warren, 2010); two provided descriptive quantitative program evaluation data (Aragon, 2006, Aragon and Le Veque, 2006); and, two provided both quantitative and qualitative program evaluation data (Program Training and Consultation Centre, 2005, Legacy, 2012). Only one article reported a randomized control trial with results pending (Matthews et al., 2014); and one study conducted a cross-sectional survey (Fallin et al., 2015).

3.3. Population age range and tailoring of programs to identity

The age of participants ranged from 18 to 72 years across all interventions and none of the studies stratified program effectiveness by age group (e.g. young LGBTQ versus older LGBTQ). As described in Table 1, ten interventions in 13 documents reported cultural tailoring of the program towards a LGBT target audience (Eliason et al., 2012, Program Training and Consultation Centre, 2005, Walls and Wisneski, 2010, Matthews et al., 2013a, Legacy, 2012, Barry, 2012, Senseman, 2008, University of California, 2002, University of California San Francisco AIDS Research Instit, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2013, Aragon, 2006, Aragon and Le Veque, 2006, Fallin et al., 2015), two interventions were tailored to gay men (Dickson-Spillmann et al., 2014, Harding et al., 2004), one intervention compared a LGBT tailored program to a non-tailored program (Matthews et al., 2014), one intervention was tailored to lesbians and women who partner with women (WPW) (Legacy, 2012), one intervention was tailored to African American men who have sex with men (MSM) and who are HIV + (Matthews et al., 2013b), and one intervention was tailored to LGBT individuals with HIV (Warren, 2010). Three programs were not tailored for the LGBTQ community but tested a program for the general population and provided results for the LGBT community (Covey et al., 2009, Grady et al., 2014, Huber et al., 2012).

3.4. Intervention – country, type, setting and mode

The interventions were primarily conducted in the USA (n = 15) (Eliason et al., 2012, Walls and Wisneski, 2010, Matthews et al., 2013a, Legacy, 2012, Covey et al., 2009, Grady et al., 2014, Matthews et al., 2013b, Barry, 2012, Senseman, 2008, University of California, 2002, University of California San Francisco AIDS Research Instit, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2013, Warren, 2010, Aragon, 2006, Aragon and Le Veque, 2006, Matthews et al., 2014, Fallin et al., 2015), followed by two in Switzerland (Dickson-Spillmann et al., 2014, Huber et al., 2012), one in Canada (Program Training and Consultation Centre, 2005) and one in the United Kingdom (Harding et al., 2004).

Most interventions provided group based counselling (n = 13) with varying degrees of individual one-on-one, peer, and/or pharmacotherapy support (Dickson-Spillmann et al., 2014, Eliason et al., 2012, Program Training and Consultation Centre, 2005, Walls and Wisneski, 2010, Matthews et al., 2013a, Grady et al., 2014, Harding et al., 2004, Matthews et al., 2013b, Barry, 2012, University of California, 2002, University of California San Francisco AIDS Research Instit, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2013, Warren, 2010, Matthews et al., 2014). Of these, six provided group counselling only (Eliason et al., 2012, Program Training and Consultation Centre, 2005, Walls and Wisneski, 2010, Matthews et al., 2013a, University of California, 2002, University of California San Francisco AIDS Research Instit, Warren, 2010), five provided group counselling along with pharmacotherapy (Matthews et al., 2013a, Grady et al., 2014, Matthews et al., 2013b, Barry, 2012, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2013, Matthews et al., 2014), and two connected participants with a general practitioner to obtain a prescription for pharmacotherapy (Dickson-Spillmann et al., 2014, Harding et al., 2004). These group based counselling programs provided face-to-face interaction in community centers, community research centers, or research clinics. Except for one program (Grady et al., 2014), all group cessation classes indicated that counsellors/facilitators were trained to conduct smoking cessation classes by specialists or groups (Harding et al., 2004, Matthews et al., 2013b, University of California, 2002, University of California San Francisco AIDS Research Instit, Warren, 2010, Matthews et al., 2014), agencies (Eliason et al., 2012, Program Training and Consultation Centre, 2005, Walls and Wisneski, 2010, Matthews et al., 2013a, Barry, 2012, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2013), or in one case, a manual (Dickson-Spillmann et al., 2014). Many of these counsellors/facilitators also identified as LGBT (Dickson-Spillmann et al., 2014, Eliason et al., 2012, Walls and Wisneski, 2010, Matthews et al., 2013a, University of California, 2002, University of California San Francisco AIDS Research Instit, Warren, 2010, Matthews et al., 2014).

Three interventions provided one-on-one counselling (Covey et al., 2009, Huber et al., 2012, Senseman, 2008), of which two were provided in a clinical setting with face-to-face interaction (Covey et al., 2009, Huber et al., 2012), and one was provided through a telephone quitline (Senseman, 2008). Three interventions were communication campaigns (Legacy, 2012, Aragon, 2006, Aragon and Le Veque, 2006, Fallin et al., 2015) that provided their programs in the community, online, and in the media with a variety of print ads, face-to-face events, websites, and social media (Legacy, 2012, Fallin et al., 2015).

3.5. Theoretical framework

Six interventions of the 19 in Table 1 reported utilizing a theoretical framework to design the intervention. Three programs cited the transtheoretical model (stages of change) (Eliason et al., 2012, Huber et al., 2012, Warren, 2010), one assessed readiness to quit and was based on cognitive behavioural therapy, motivational interviewing, and 12-step addiction techniques (Matthews et al., 2013b), one used the transtheoretical model and the health belief model (Matthews et al., 2014), and one used social cognitive theory and the transtheoretical model (Program Training and Consultation Centre, 2005).

3.6. Outcomes

3.6.1. Group counselling programs for LGBTQ + persons

The thirteen identified smoking cessation group counselling interventions were primarily community driven and lasted between six and eight weeks on average. Two of the group cessation interventions (Matthews et al., 2013a, Grady et al., 2014) included the combination of counselling and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or pharmacotherapy as the combination of behavioural counselling and pharmacotherapy is more effective than pharmacotherapy alone (Fiore et al., 2008). In the United Kingdom, a group program for the gay community showed favourable results with 64% quitting by the seventh week with biomarker confirmation using carbon monoxide (CO) testing (Harding et al., 2004). Of those who had set a quit date, 76% were confirmed to have quit, compared with 53% of those nationally who had also set a quit date (Harding et al., 2004). This program was replicated in Switzerland as Queer Quit, where 66% had quit at week seven (intent to treat; ITT) and 29% had quit at six month follow-up (ITT) (Dickson-Spillmann et al., 2014).

A Canadian intervention tailored to LGBT entitled Stop Dragging Your Butt obtained self-report data and found that out of those completing a survey at the eighth session, 45% reported quitting completely (19% ITT) and 85% felt the program was excellent and very useful when tailored (Program Training and Consultation Centre, 2005). As an example of tailoring, Stop Dragging Your Butt conducted a focus group with gay men who identified the following issues for inclusion in programming: isolation, bar culture, self-esteem, empowerment, high-risk behaviours, peer pressure, image and lifestyle, and desire for connection and authenticity (Program Training and Consultation Centre, 2005). Other adaptions to general population cessation resources included reflecting the language and context of the LGBT community, recognizing social life is linked to bars and group outings, giving attention to physical appearance, and recognizing living situations of community members (Program Training and Consultation Centre, 2005).

A commonly cited tailored group cessation program is The Last Drag, which was created initially by the Coalition of Lavender Americans on Smoking and Health (CLASH) in 1991. This program has been adapted and offered in the US for a number of years with favourable results. Implementation of this program in San Francisco found 59% had quit (ITT) at the seventh session and 36% had quit (ITT) at six month follow-up (Eliason et al., 2012). Implementation in Colorado found that 89% of individuals reported quitting at the final session (Walls and Wisneski, 2010). However, Eliason et al. (2012) found that those who were female, ethnic, and/or transgendered were less likely to attend more than one class and had lower rates of success. A similar program in San Francisco entitled QueerTIPS also found a 40% self-report quit at the final session, but that few transgendered individuals and youth attended the program (University of California, 2002, University of California San Francisco AIDS Research Instit). This program identified a need for interventions to be multi-leveled in targeting those in each stage of change.

Multiple programs have also been formulated based on the American Lung Association's Freedom from Smoking Program. These programs, Call It Quits, Bitch to Quit, and Put It Out, were tailored to LGBT and found a 32% ITT quit rate one-month following the quit date across all three programs (Matthews et al., 2013a). Individual quit rates for these three programs were 39% (ITT; Call It Quits), 23% (ITT; Put It Out), and 27% (ITT; Bitch to Quit) at one month (Matthews et al., 2013a). One intervention, Courage to Quit, is undergoing a randomized control trial to evaluate a culturally targeted intervention versus a non-targeted intervention (Matthews et al., 2014). Another program, Project Exhale (based on Courage to Quit), is tailored to those who are African American, are MSM, and are HIV + (Matthews et al., 2013b). Quit rates were verified via CO testing and found to be 24% at month one based on self-report and 16% ITT (Matthews et al., 2013b).

The LGBT SmokeFree Project in New York is tailored to those who are LGBT and have HIV (Warren, 2010). This program provides programming dependent on a person's stage of change, including a workshop for those thinking about quitting, and group sessions for those in the preparation/action stages (Warren, 2010). Program-level data indicated that individuals appreciated the group experience that kept them coming back, trusted the community center, and many returned incentives for participation in gratitude of quitting successfully (Warren, 2010). The majority of participants in this program felt an LGBT-specific program to be important (Warren, 2010).

Lastly, researchers conducted a secondary analysis of two RCTs that provided non-tailored, group-based counselling (Grady et al., 2014). In this study, no differences were found between heterosexuals versus sexual and gender minorities in their quit rates (40% vs 38% at week 104 follow-up, verified by CO and biochemical testing) (Grady et al., 2014).

3.6.2. Individual counselling

Three interventions provided smokers with individual-level support for smoking cessation. Researchers in Switzerland implemented a half-day training, given by the Swiss Lung Association, on cessation counselling and pharmacotherapy for physicians in a HIV clinic (Huber et al., 2012). This training was not tailored specifically to address the needs of LGBTQ +. After training, data were collected from smokers visiting clinics where it was found that brief cessation counselling occurred for 80% of current smokers. The training of physicians was found to increase cessation, but there were no significant differences between heterosexuals and MSM (Huber et al., 2012).

Call It Quits in Minnesota implemented a LGBT tailored training for quitline counsellors to assist in identifying those who are LGBT and to provide these callers with tailored, one-on-one support (Senseman, 2008). Lessons learned were that the training was greatly appreciated and there was community support for the initiative. However, the program found that even with promotion, most LGBT community members were not aware of the quitlines in Minnesota.

Finally, in a post-hoc analysis of a RCT, male participants were provided with a non-tailored individual counselling program in combination with NRT or pharmacotherapy (Covey et al., 2009). There were no significant differences between heterosexual men, and gay and bisexual men in smoking cessation (57% vs 59% at the final session, verified by CO testing) (Covey et al., 2009).

3.6.3. Communication campaigns

The three remaining interventions were communication strategies that all had an online presence, media coverage, and face-to-face peer outreach events in bars and nightclubs. The Last Drag was adapted in Los Angeles for LGBT persons with the campaign slogan “Breath Easier. Play Harder” (Aragon, 2006, Aragon and Le Veque, 2006). This program obtained media coverage (unpaid), with many hits to their website, print impressions, and blogs discussing the campaign (Aragon, 2006, Aragon and Le Veque, 2006). Delicious Lesbian Kisses targeted lesbians and women who partner with women through a social marketing campaign, and found that women who were seeking cessation services in Washington increased by 100% and that campaign promotional items were still around in 2012, seven years after the end of the campaign (Legacy, 2012). CRUSH took the campaign one step further by encouraging LGBT young adult community members to text brand ambassadors in order to receive a text messaging cessation program (Legacy, 2012, Fallin et al., 2015). Evaluation of CRUSH found that 53% of survey respondents reported exposure to the campaign and of those, 61% liked the campaign and 86% understood the campaign message (Legacy, 2012, Fallin et al., 2015). In a cross-sectional survey of CRUSH, tobacco use dropped from 47% currently smoking at baseline to 40% at follow-up (Fallin et al., 2015). Overall smoking rates in Nevada, where CRUSH took place, fell from 63% in 2005 to 47% in 2008 (Legacy, 2012).

4. Discussion

The scoping review identified 19 tobacco use interventions targeting LGBTQ + smokers, the majority of which were set in the US and provided group cessation or face-to-face counselling with demonstrated effectiveness for smoking cessation. Further, only three interventions were population-based smoking cessation campaigns and only one of these was targeted to LGBT young adults. Cessation counselling, although effective, has limited reach in comparison to media campaigns; however, the scoping review identified limited smoking cessation outcome data for the population-based campaigns reviewed.

Almost half of the studies identified in the scoping review are not in the peer reviewed literature. These findings are similar to Lee and colleagues (Lee et al., 2014), who found 43% of the literature on treatment of tobacco dependence among LGBT populations to be grey. Lee and colleagues (Lee et al., 2014) concluded that the best available evidence concerning LGBT smoking cessation is based on group interventions with the lowest reach. They emphasized the need to invest in systems-based interventions, targeted media campaigns, and policy interventions. Our scoping review concurs with these findings; however, Lee and colleagues (Lee et al., 2014) did not comment on the methodological rigour of the studies identified. We found that the majority of studies were non-randomized, quasi-experimental before and after designs with no comparison conditions; as a consequence, the internal validity of the research to date can be called into question due to selection bias or motivation bias. We identified only one RCT paper designed to test the effectiveness of culturally tailored versus non-tailored GCC (Matthews et al., 2014). More rigorous designs on LGBTQ smoking prevention and cessation interventions such as RCTs or longitudinal studies would increase confidence in the findings reported.

Only one-third of the articles identified a theoretical framework for the development and design of the smoking cessation intervention. Theory is critical to understanding the factors that influence behaviour and underpins the choices of intervention components and how they are intended to work (French et al., 2012). Application of theory in the design of interventions assists in the evaluation of effectiveness, particularly in under researched areas such as the prevention and cessation of smoking among LGBTQ + YYA.

4.1. Implications for practice

There are important policy and practice considerations stemming from this scoping review. Notably, the limited evidence and literature evaluating LGBTQ + smoking prevention and cessation programs for YYA (with the exception of CRUSH) limits the ability for practitioners and policy makers to implement effective prevention and cessation strategies for this priority population. However, GCC for the LGBTQ + community as a whole is feasible to implement and shows evidence of effectiveness. Community-based programs have also been successfully implemented, although very little evidence of prevention or cessation outcomes exist. There is information available on what the LGBTQ + youth community desires in terms of a prevention or smoking cessation intervention (Remafedi, 2007, Remafedi and Carol, 2005, Chanel et al., 2013). For example, practitioners can become more familiar with the LGBTQ + YYA psychosocial and cultural underpinnings of tobacco use such as smoking as a coping mechanism for victimization. The perspective of LGBTQ + youth combined with evidence-based intervention development (Fiore et al., 2008) is an important next step to address the problem of tobacco among LGBTQ + YYA.

The scoping review also identified a lack of interventions for transgendered and queer population groups. For example, the review identified studies where the transgender participation rate was only between 2.3% and 4.1%. Research on within-group differences (e.g., transgendered versus bisexual and racial/ethnic differences) is important for practitioners to understand conditions needed to reach and help specific LGBTQ + sub-populations to quit smoking (Gamarel et al., 2016, Youatt et al., 2015). Further, there is little to no guidance for practitioners on prevention programming for LGBTQ + YYA nor is there anything on the impact of policy interventions such as smoke-free spaces or tobacco tax increases for this population, despite the evidence that comprehensive tobacco control policy or system changes are the most efficient and effective in reaching and encouraging people to quit smoking (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). A key finding from the review was the absence of evidence to guide cessation programming for LGBTQ + YYA as well as the absence of prevention programming for LGBTQ adolescents. This is despite the fact that > 200 school-based effectiveness studies on smoking prevention programs have been published, albeit none with consideration of gender and sexual identity student minorities (Onrust et al., 2016). However, evidence supports that the presence of Gay-Straight Alliances in schools, as well as school policies (non-discrimination and anti-bullying) that specifically protect LGBTQ + students, results in lower tobacco use (Poteat et al., 2013).

4.2. Implications for research

Given the paucity of research on prevention and cessation interventions for LGBTQ + YYA, there are a number of areas for further improvement. There is considerably more literature on the prevalence of smoking in the LGBTQ + youth population (Marshal et al., 2008) as well as the aetiology for smoking (Blosnich et al., 2013, Hatzenbuehler et al., 2011) among youth, yet comparatively very little evidence on tobacco-related interventions for prevention and cessation in LGBTQ + YYA. Research is desperately needed; given the significance of youth development and the transition to young adulthood (Youatt et al., 2015), the findings from studies focused primarily on the LGBTQ + adult interventions cannot be assumed to be relevant to the youth and young adult population. Research specific to outcomes in LGBTQ + YYA related to the impact of tobacco prevention and cessation mass-media campaigns (Atusingwize et al., 2014), new technology-based interventions such as text-messaging (Baskerville et al., 2016, Civljak et al., 2013, Whittaker et al., 2012), cessation programs adapted to the community, and policy interventions such as cigarette price increases (Hoffman and Tan, 2015, Peretti-Watel et al., 2009) should be encouraged to fill this important knowledge gap.

Further, the scoping review identified that the majority of published literature is based on descriptive program evaluations or non-randomized, quasi-experimental designs with no comparison group; half of the studies were published in the non-peer reviewed grey literature. While this literature can be informative, it suffers from a lack of rigour and raises questions regarding the validity of findings. Better controlled studies or longitudinal designs on prevention, cessation and policy interventions for LGBTQ + YYA are recommended. In addition to the problems of research design, the literature lacks consistency in terms of outcome measures regarding smoking. For example, some studies used either 7-day or 30-day point prevalence abstinence, some only reported current smoking at end of program, others reported an intent-to-treat smoking rate, others conducted biochemical validation of smoking status whereas others relied on self-report. Outcome measures also varied in terms of length of follow-up after the intervention. Consistency in the reporting of outcomes (Copley et al., 2006, West et al., 2005) greatly assists in the review of evidence and decision-making on the effectiveness of interventions. A full systematic review of the literature is unadvisable given the methodological weaknesses and inconsistency in reporting across studies.

Lee and colleagues (Lee et al., 2014) concluded that evidence-based, non-tailored tobacco treatments work as well for LGBT people as for non-LGBT people. In contrast, other research has shown that programming needs to be LGBTQ + focused and the community needs to be involved in the planning, design, development, and implementation of programs (Remafedi, 2007, Haas et al., 2011). Similar to the findings of Berger and Mooney-Somers (Berger and Mooney-Somers, 2016), the majority (16 interventions; 18 documents) of studies in this review described interventions that were culturally tailored. Programming needs to be tailored specifically to sub-populations of the LGBTQ + youth community as these sub-populations may be at greater risk for tobacco use (e.g. transgendered, homeless youth, club-goers, substance abusers, etc.) (Gamarel et al., 2016, Remafedi, 2007). Ideally, programming and its delivery needs to be culturally sensitive to a program's target audience, inclusive and perceived to be LGBTQ + safe. An effective non-tailored program will not matter if the target community does not perceive the program to be LGBTQ + focused as they likely will not use it (Burkhalter, 2015). Research is needed to demonstrate LGBTQ + youth and young adult participation in tobacco prevention and cessation interventions, as well as effectiveness of LGBTQ + tailored versus non-tailored interventions across different sub-populations and settings.

Finally, the research community must work to conduct implementation studies to assist decision-makers in program design, answer questions concerning program acceptability for different LGBTQ + youth and providers, and identify which intervention components are the most effective for whom, with what level of intensity, duration and at what cost. However, there are some logistical challenges of intervention studies in this population. Specifically, recruitment can be an issue as many LGBTQ + YYA have not “come out” and/or are homeless or couch surfers (i.e., staying as a guest on people's couches) and thus, may be difficult to reach to participate in these intervention studies. Being able to recruit LGBTQ YYAs in urban cities versus rural areas would be another logistical challenge of intervention studies in this population as urban YYAs would likely have easier access to transportation and support mechanisms to participate compared to rural YYAs. The information taken from implementation studies is vital for the eventual scaling-up and adaptation of programs for LGBTQ + YYA (Chambers et al., 2013, Davidson et al., 2013, Milat et al., 2016).

4.3. Strengths and limitations

The review was limited to publications in English. Accordingly, it is possible that some studies were not identified using the search strategies outlined in this paper. While alcohol use, cannabis, tobacco and other health risk behaviours may occur together, we focused on tobacco use which precluded the inclusion of intervention studies that were not primarily focused on tobacco. Some programs are over represented in the review (e.g., The Last Drag); however, the included articles were independent studies with different populations. An aim of the scoping review was to describe the current state of both practice and science in the focused area of LGBTQ + YYA smoking cessation and prevention and selection bias was mitigated with explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria and having two independent reviewers for article selection and extraction of information. The scoping review revealed only one study specifically on smoking cessation for LGBTQ + YYA.

5. Conclusions

There is very little evidence on effective smoking cessation and prevention programs and policies for LGBTQ + YYA. The evidence to date is drawn from methodologically weak studies for the LGBTQ + population as a whole. In addition, there is limited evidence to guide the implementation and dissemination of tobacco prevention and cessation programs for LGBTQ + YYA. Unfortunately, in the absence of a strong evidence base specific to LGBTQ + YYA, health promotion policy makers and practitioners will need to draw on parallel evidence from other settings or target populations to address the question of what works to help LGBTQ + youth quit smoking, as well as to develop strategies to facilitate the adoption of tobacco use prevention and cessation programs for LGBTQ + YYA. There is a need for effective, community-informed, and engaged interventions specific to LGBTQ + YYA for the prevention and cessation of tobacco.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ontario Ministry of Health, Health Services Research Fund (grant #06696), and the Canadian Cancer Society Research Initiative (grant #701019).

Analysis of the Canadian Community Health Survey was supported by funds to the Canadian Research Data Centre Network (CRDCN) from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR), the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI), and Statistics Canada. Although estimates are based on data from Statistics Canada, the opinions expressed do not represent the views of Statistics Canada.

Authors' contributions

NBB led the conceptualization and design of the study and JY, RDK, JY, KW, AS, and AA, contributed to the design of the study. DD and NBB drafted the manuscript. KW, AS, AA, JY, and RDK critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. NBB and JY are co-principal investigators and RDK is a co-investigator on the research funding application. DD, KW, AS and AA provided administrative, technical, and material support. NBB supervised the study. NBB is the guarantor.

Acknowledgements

We thank Aamer Esmail and Anna Travers from Sherbourne Health Centre, Toronto, Ontario and Rainbow Heath Ontario for assistance in conducting the research and helpful comments. We also would like to thank the Editor of this journal and the anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Warning: Marginal sampling variability – interpret with caution.

References

- Aragon L. 2006. Last Drag LA: A Multi-faceted Media Campaign to Reach the LGBT Population [Internet] (cited 2016 Apr 13). (Available from: http://2006.confex.com/uicc/wctoh/techprogram/P8729.HTM) [Google Scholar]

- Aragon L., Le Veque M. Los Angeles County Tobacco Control and Prevention Program; Washington, DC: 2006. The Last Drag Campaign: Countering the Tobacco Industry's Targeting of the Gay and Lesbian Community. (Available from: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/tob/pdf/Banner-C.6.29.6.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005 Feb 1;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong R., Hall B.J., Doyle J., Waters E. Cochrane update. “scoping the scope” of a Cochrane review. J. Public Health Oxf. Engl. 2011 Mar;33(1):147–150. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atusingwize E., Lewis S., Langley T. 2014 Jul 1. Economic Evaluations of Tobacco Control Mass Media Campaigns: A Systematic Review. Tob Control [Internet] (cited 2016 Apr 14). (Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2014/07/01/tobaccocontrol-2014-051579) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azagba S., Asbridge M., Langille D., Baskerville B. Disparities in tobacco use by sexual orientation among high school students. Prev. Med. 2014 Dec;69:307–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry R. 2012. It's a Bitch to Quit: Interview With Dr. Phoenix Matthews [Internet] (cited 2016 Apr 13). (Available from: http://thelstop.org/2012/11/its-a-bitch-to-quit-interview-with-dr-phoenix-matthews/) [Google Scholar]

- Baskerville N.B., Azagba S., Norman C., McKeown K., Brown K.S. Effect of a digital social media campaign on young adult smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016 Mar;18(3):351–360. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger I., Mooney-Somers J. Smoking cessation programs for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex people: a content-based systematic review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016:1–10. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J., Lee J.G.L., Horn K. A systematic review of the aetiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities. Tob. Control. 2013 Mar;22(2):66–73. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhalter J.E. Smoking in the LGBT community. In: Boehmer U., Elk R., editors. Cancer and the LGBT Community [Internet] Springer International Publishing; 2015. pp. 63–80. (cited 2016 Apr 14). (Available from: http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-15057-4_5) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, U.S.: 2014. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs—2014 [Internet] (cited 2017 Feb 5). (Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices/) [Google Scholar]

- Chambers D.A., Glasgow R.E., Stange K.C. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement. Sci. 2013;8:117. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanel R.C.C., Palmer J., Biggz D. 2013. Why You Puffin'? A Photovoice Project 2013. (Toronto, ON) [Google Scholar]

- Civljak M., Stead L.F., Hartmann-Boyce J., Sheikh A., Car J. Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007078.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M.P., Coughlin J.R. Prevalence of smoking among the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, transgender and queer (LGBTTQ) subpopulations in Toronto-the Toronto Rainbow Tobacco Survey (TRTS) Can. J. Public Health. 2012 Apr;103(2):132–136. doi: 10.1007/BF03404218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copley T., Lovato C., O'Connor S. National Advisory Group on Monitoring and Evaluation. Canadian Tobacco Control Research Initiative; Toronto, ON: 2006. Indicators for Monitoring Tobacco Control: A Resource for Decision-Makers, Evaluators and Researchers. [Google Scholar]

- Covey L.S., Weissman J., LoDuca C., Duan N. A comparison of abstinence outcomes among gay/bisexual and heterosexual male smokers in an intensive, non-tailored smoking cessation study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2009 Nov 1;11(11):1374–1377. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daudt H.M.L., van Mossel C., Scott S.J. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013 Mar 23;13:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E.M., Liu J.J., Bhopal R. Behavior change interventions to improve the health of racial and ethnic minority populations: a tool kit of adaptation approaches. Milbank Q. 2013 Dec;91(4):811–851. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K., Drey N., Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009 Oct;46(10):1386–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson-Spillmann M., Sullivan R., Zahno B., Schaub M.P. Queer Quit: a pilot study of a smoking cessation programme tailored to gay men. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolan D.M., Froelicher E.S. Efficacy of smoking cessation intervention among special populations: review of the literature from 2000 to 2005. Nurs. Res. 2006 Aug;55(4 Suppl):S29–S37. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200607001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason M.J., Dibble S.L., Gordon R., Soliz G.B. The Last Drag: an evaluation of an LGBT-specific smoking intervention. J. Homosex. 2012 Jul;59(6):864–878. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2012.694770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallin A., Neilands T.B., Jordan J.W., Ling P.M. Social branding to decrease lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young adult smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015 Aug 1;17(8):983–989. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M.C., Jaen C., Baker T. Clinical Practice Guideline. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: 2008. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. [Google Scholar]

- French S.D., Green S.E., O'Connor D.A. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement. Sci. 2012;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel K.E., Mereish E.H., Manning D., Iwamoto M., Operario D., Nemoto T. Minority stress, smoking patterns, and cessation attempts: findings from a community-sample of transgender women in the San Francisco Bay Area. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016 Mar;18(3):306–313. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentium Consulting . Program Training and Consultation Centre; Ottawa, ON: 2005 Jan. Smoking Cessation and the GLBT Community [Internet] (Available from: http://www.lgbttobacco.org/files/Canada%20GLBT%20Cessation%20Evaluation.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Grady E.S., Humfleet G.L., Delucchi K.L., Reus V.I., Muñoz R.F., Hall S.M. Smoking cessation outcomes among sexual and gender minority and nonminority smokers in extended smoking treatments. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014 Sep 1;16(9):1207–1215. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A.P., Eliason M., Mays V.M. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. J. Homosex. 2011;58(1):10–51. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding R., Bensley J., Corrigan N. Targeting smoking cessation to high prevalence communities: outcomes from a pilot intervention for gay men. BMC Public Health. 2004 Sep 30;4:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler M.L., Wieringa N.F., Keyes K.M. Community-level determinants of tobacco use disparities in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: results from a population-based study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2011 Jun;165(6):527–532. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Statistics Division, Statistics Canada . Statistics Canada; Ottawa, ON: 2015. Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) Annual Component 2013–2014 Microdata File. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman S.J., Tan C. Overview of systematic reviews on the health-related effects of government tobacco control policies. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:744. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard Brown. You've Come a Long Way, Baby: Chicago Style [Internet]. n.d. (Available from: http://www.lgbttobacco.org/files/Chicago%20LGBT%20Tobacco%202008%20Creating%20Change.pdf)

- Huber M., Ledergerber B., Sauter R. Outcome of smoking cessation counselling of HIV-positive persons by HIV care physicians. HIV Med. 2012 Aug;13(7):387–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.G.L., Matthews A.K., McCullen C.A., Melvin C.L. Promotion of tobacco use cessation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: a systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014 Dec;47(6):823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legacy . 2012 Dec. Tobacco Control in LGBT Communities. (Washington, DC) [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O'Brien K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal M.P., Friedman M.S., Stall R. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008 Apr;103(4):546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews A.K., Li C.-C., Kuhns L.M., Tasker T.B., Cesario J.A. Results from a community-based smoking cessation treatment program for LGBT smokers. J. Environ. Public Health. 2013;2013:984508. doi: 10.1155/2013/984508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews A.K., Conrad M., Kuhns L., Vargas M., King A.C. Project Exhale: preliminary evaluation of a tailored smoking cessation treatment for HIV-positive African American smokers. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013 Jan;27(1):22–32. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews A.K., McConnell E.A., Li C.-C., Vargas M.C., King A. Design of a comparative effectiveness evaluation of a culturally tailored versus standard community-based smoking cessation treatment program for LGBT smokers. BMC Psychol. 2014 May 30;2(1):12. doi: 10.1186/2050-7283-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milat A.J., Newson R., King L. A guide to scaling up population health interventions. Public Health Res. Pract. 2016;26(1) doi: 10.17061/phrp2611604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb M.E., Heinz A.J., Birkett M., Mustanski B. A longitudinal examination of risk and protective factors for cigarette smoking among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. J. Adolesc. Health. 2014 May;54(5):558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onrust S.A., Otten R., Lammers J., Smit F. School-based programmes to reduce and prevent substance use in different age groups: what works for whom? Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016 Mar;44:45–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretti-Watel P., Villes V., Duval X. How do HIV-infected smokers react to cigarette price increases? Evidence from the APROCO-COPILOTE-ANRS CO8 cohort. Curr. HIV Res. 2009 Jul;7(4):462–467. doi: 10.2174/157016209788680624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham M.T., Rajić A., Greig J.D., Sargeant J.M., Papadopoulos A., McEwen S.A. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res. Synth. Methods. 2014 Dec;5(4):371–385. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat V.P., Sinclair K.O., DiGiovanni C.D., Koenig B.W., Russell S.T. Gay–straight alliances are associated with student health: a multischool comparison of LGBTQ and heterosexual youth. J. Res. Adolesc. 2013 Jun 1;23(2):319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Program Training and Consultation Centre . Program Training and Consultation Centre; Ottawa, ON: 2005. Smoking Cessation and the Gay, Lesbian, Bi-sexual or Trans-gendered (GLBT) Community Initiative [Internet] (Available from: https://www.ptcc-cfc.on.ca/cms/One.aspx?portalId=97833&pageId=104753) [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi G. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths: who smokes, and why? Nicotine Tob. Res. 2007 Jan;9(Suppl. 1):S65–S71. doi: 10.1080/14622200601083491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi G., Carol H. Preventing tobacco use among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2005 Apr;7(2):249–256. doi: 10.1080/14622200500055517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson W.S., Wilson M.C., Nishikawa J., Hayward R.S. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J. Club. 1995 Dec;123(3):A12–A13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senseman S. National LGBT Tobacco Control Network; Boston, MA: 2008. Making Minnesota's Quitlines Accessible to LGBTs [Internet] (Available from: http://www.lgbttobacco.org/files/SOL%20V2%20_quitlines.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- University of California . 2002. QueerTIPs for LGBT Smokers: A Stop Smoking Class for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Communities: Facilitator's Manual [Internet] (San Francisco, CA) (Available from: http://www.lgbttobacco.org/files/QueerTIPsrevManual.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- University of California San Francisco AIDS Research Institute . 2002. Smoking Cessation Interventions in San Francisco's Queer* Communities [Internet] San Francisco, CA. Report No.: Prevention #11. (Available from: http://caps.ucsf.edu/uploads/pubs/reports/pdf/Q-TIPS2C.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- University of Illinois at Chicago . University of Illinois; Chicago, IL: 2013. It's A Bitch To Quit. (Report No.: Winter 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Walls N.E. The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Community Center of Colorado; Denver CO: 2008. Evaluation of the Last Drag Smoking Cessation Classes Offered to the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, & Transgender Communities of Colorado. [Google Scholar]

- Walls N.E., Wisneski H. Evaluation of smoking cessation classes for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2010 Dec 8;37(1):99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Warren B. National LGBT Tobacco Control Network; Boston, MA: 2010. Positively Smokefree: Helping HIV + Smokers to Quit [Internet] (Available from: http://lgbttobacco.org/files/HIV%20SOL%20Final.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- West R., Hajek P., Stead L., Stapleton J. Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction. 2005 Mar;100(3):299–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker R., McRobbie H., Bullen C., Borland R., Rodgers A., Gu Y. Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006611.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youatt E.J., Johns M.M., Pingel E.S., Soler J.H., Bauermeister J.A. Exploring young adult sexual minority women's perspectives on LGBTQ smoking. J. LGBT Youth. 2015;12(3):323–342. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2015.1022242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]