Highlights

-

•

The use of VAC therapy is amply demonstrated in the literature as an adjuvant in the open abdomen technique.

-

•

Today VAC therapy have not a definite indication in secondary septic peritonitis.

-

•

In our case, VAC therapy wasn’t a rescue treatment, but a preventive treatment of high-risk perioperative complications.

-

•

A conservative approach led to the resolution of the septic shock and to the wound healing.

Abbreviations: L-T, latero to terminal; ICU, intensive care unite; VAC, vacuum assisted closure; IAP, intra-abdominal hypertension; NPT, negative pressure therapy; BVPT, Barker’s vacuum pack technique; NPWT, negative pressure wound therapy

Keywords: VAC therapy, Open abdomen, Negative pressure therapy, Septic peritonitis

Abstract

Background

The management of a septic peritonitis open abdomen is a serious problem for clinicians. Open surgery is associated with several complications such as bleeding and perforation of the bowel.

Case presentation

The authors report a case of a 59-years-old female who underwent a sigmoid resection with an latero-terminal (L-T) anastomosis for the perforation of a diverticulum. After a few days the patients developed a new widespread peritonitis. At the emergency re-laparotomy, surgeons found dehiscence of the posterior wall of the anastomosis with fecal contamination. At admission in ICU (Intensive Care Unit) the patient had open abdomen with dehiscence of cutaneous and subcutaneous layers.

Conclusion

Conservative therapy with antibiotic therapy and use of the Vacuum-Assisted Closure® (VAC) Therapy with a long term continuous saline infusion led to the resolution of the septic shock and to the wound healing.

1. Background

Open surgery for damage control in critically ill patients with septic peritonitis open abdomen is associated with several complications such as bleeding and perforation of the bowel. There are four major indications for the use of the open abdomen technique: damage control for life-threatening intra-abdominal bleeding, prevention or treatment of intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH), management of severe intra-abdominal sepsis [1] and when a re-laparotomy is needed [2].

In the case presented, the medical team decided to use conservative therapy applying negative pressure therapy (NPT) techniques. The two most commonly used NPT techniques are Barker’s vacuum pack technique (BVPT) and Vacuum-Assisted-Closure® Therapy [V.A.C.® Abdominal Dressing System (ADS); KCI USA] [1].

2. Case presentation

We describe the case of a 59-year-old female patient that was admitted to a peripheral hospital with diagnosis of peritonitis secondary to a perforation of a sigmoid diverticulum. She underwent a sigmoid resection with an L-T anastomosis. After 11 days, the patients developed a new widespread peritonitis. At emergency re-laparotomy, surgeons found dehiscence of the posterior wall of the anastomosis with fecal contamination of the abdomen. They carried out an ileostomy with careful toilet of peritoneal cavity, and they left the wound margins not juxtaposed for the high risk of complications. Due to the aggravation of the clinical features and after further 23 days, it was decided to transfer the patient at our ICU continuation of intensive care. On ICU admission, the patient was sedated, intubated and mechanically ventilated. She was hemodynamically unstable (invasive blood pressure of 80/50 mmHg), no fluid load responder and body temperature was 38 °C. The patient presented dehiscence of cutaneous and subcutaneous abdominal layers (Fig. 1). In her history, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gastro-esophageal reflux disease, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation have been reported.

Fig. 1.

Open abdomen after abdominal tissue dehiscence.

Culture tests were collected. Surgical wound swab was positive for E. coli, E. faecius, and Bacteroides Ovatum, meanwhile blood cultures had a negative outcome.

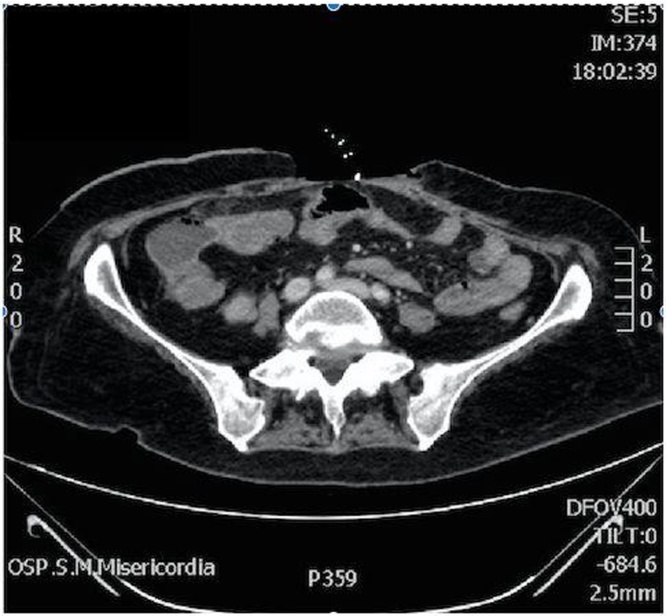

A CT scan of the abdomen showed free air in peritoneal cavity surrounding the liver and spleen, especially in the epigastrium and mesogastrium (Fig. 2). Multiple confluent abscesses were identified in the right and left hypocondrium (the largest measured 52 mm × 35 mm) and in the pelvic cavity (with the largest of 26 mm × 25 mm) (Fig. 3). Other findings indicated the presence of multiple nodules in the chest compatible, in the first hypothesis, with septic localizations and the existence of multiple ipodense areas within the spleen related to heart-failure.

Fig. 2.

Free air in peritoneal cavity.

Fig. 3.

Multiple abscesses in pelvic cavity.

An intervention of debridement was rejected because of the severe physical conditions of the patient and because abdominal abscesses were not considered treatable by surgery as they were multiple and disseminated. For this reason, we proposed a conservative treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and the use of Negative Pressure Therapy (NTP). This treatment was at high risk of both hemorrhage and perforation because the loops were free of fascial closure and made fragile by infection.

We performed VAC therapy with the lowest possible continuous negative pressure (−15 mmHg) for the high risk of bleeding and perforation. We applied V.A.C. VeraFlo Cleanse™ in place of conventional medications (foam dressings of the V.A.C.® Therapy System). The material of this foam is black polyurethane ester, with a median hydrophobicity and pore size of 400–600 μm. This foam allowed us to perform intermittent cleaning cycles (of the approximate duration of 5 min) with saline infusion alternating suction phases (of duration of 50 min) during the day. Only after 4 weeks of NTP the patient achieved the formation of a clinically adequate granulation tissue (Fig. 4). This, combined whit the resolution of the septic state and a more stable hemodynamic status of the patient, allowed us to apply the conventional GranuFoam™ Dressings (black polyurethane ether) (Fig. 5) to prosecute the NTP, stopping the washing of the wound bed. Tissue repair, so accelerated by the NPT, permitted surgeons to shorten the time for the progressive juxtaposition of the flaps. After 35 days, the patient was discharged from the ICU. The patient was afebrile, clinically and hemodynamically stable, had spontaneous breathing with oxygen therapy and normal urine output. She continued VAC therapy for other 4 weeks on the ward until the complete closure of the abdominal wall (Fig. 6). After six months, the patient was alive and no complications occurred.

Fig. 4.

Abdomen after the first days of the VAC ® Therapy.

Fig. 5.

V.A.C.® GranuFoam™ Dressings.

Fig. 6.

Resolution.

3. Conclusion

The VAC (Vacuum-Assisted Closure) therapy (also know as NPWT, negative pressure wound therapy) is a non-invasive active wound management technique which exposes wound bed to continuous or intermittent local sub atmospheric pressure [2].

Microdeformational Wound Therapy (MDWT) is a particular technique of VAC. The system consists of a unit which actuates the suction, an impermeable membrane and a soft and porous foam that is placed over the wound. The application of suction guarantees a negative pressure that exposes the wound margins to macro and micro deformations. The macro-deformation sustained through the foam allows the approximation of the margins and the removal of exudate. The micro-deformation instead acts at the cellular level, with the promotion of the proliferation and migration of cells. These physical interactions stimulate cell regeneration and the formation of granulation tissue [3].

The effectiveness of this technique has been documented mainly in patients with trauma or compartmental syndrome. There are few studies regarding the use of this technique in patients with peritonitis, but Horwood et al. asserted that an early use of the V.A.C. ® Therapy may reduce complications compared to laparotomy in abdominal infections [4]. Patients who appear to benefit most of VAC ® Therapy have been grouped into several categories [5]:

-

•

patients with anastomotic dehiscence;

-

•

unstable patients with hypothermia, acidosis and coagulopathy;

-

•

edema of the abdominal wall or bowel that results in difficulty of closing;

-

•

unidentified source of the sepsis;

-

•

uncontrolled sepsis;

-

•

when a re-laparotomy is needed;

-

•

severe fecal peritonitis.

Possible complications of the use of the V.A.C. ® Therapy are bleeding, pain, fluid loss [6], and creation of entero-fistulas (20%) [7]. The duration of the therapy is based on clinical judgment considering the risk-benefit assessment [8]. It is based on neoformation of granulation tissue which is a sign of tissue regeneration [9].

In our case, the patient’s critical status (secondary septic peritonitis), the presence of multiple abscesses and the surgical assessment, that the many adhesions between intestinal loops were at high risk of stenosis and perforation to the approximation of the flaps, suggested us to begin a conservative treatment.

We used a NPT with continuous washing fluids as an adjuvant treatment to parenteral antibiotic therapy to achieve the elimination of infectious materials and exudate, the continuous cleaning of the abdominal cavity, the reduction of edema, and the development of the granulation tissue.

We applied the lowest possible negative pressure (−15 mmHg) for a continuous time of 8 weeks for the high risk of perforation and stenosis of the loops.

Although regardless an off-label treatment, we achieved clinical benefits after 4 weeks (resolution of peritonitis, formation of an adequate granulation tissue, hemodynamic stability), and so we could apply the conventional GranuFoam™ that allowed to accelerate tissue repair and to perform the progressive approach of the flaps. Despite the high incidence of complications reported in the literature [7], no complication occurred related to the VAC in our case. Definitely, the not neoplastic nature of the initial disease (confirmed by histological examination of the surgical piece) allowed us to apply VAC therapy safely.

Although the use of VAC therapy is amply demonstrated in the literature as an adjuvant in the open abdomen technique, today there is no definite indication for its use in patients with secondary septic peritonitis.

In this case, we achieved a clinical success with a strong reduction of perioperative risk (stenosis or perforation) applying a very low negative pressure (−15 mmHg) for a prolonged time (8 weeks), with intermittent cycles of instillation. So, our experience suggests to use the VAC therapy as an adjuvant treatment in all those cases of patients with septic peritonitis in which perioperative risks are too high. We emphasize the fact that this choice should not be undertaken as a rescue treatment, but as a preventive treatment of high-risk perioperative complications.

Competing interests

The authors declare there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this article.

Funding

No funding source has participated or contributed to the realization of this study.

Ethical approval

Our manuscript describes a case report that occurs in our hospital. There was no need to consult the ethics committee.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Authors' contributions

Fulvio Nisi: Drafting of manuscript.

Federico Marturano: Drafting of manuscript, Literature search.

Eleonora Natali: Literature search, Data collection.

Antonio Galzerano: Data collection, Analisys of the case.

Patrizia Ricci: Consultant surgeon, Review of manuscript.

Vito Aldo Peduto: Review of manuscript.

The work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [10].

Guarantor

Federico Marturano.

Contributor Information

Fulvio Nisi, Email: fulvio.nisi@gmail.com.

Federico Marturano, Email: federicomarturano@msn.com.

Eleonora Natali, Email: eleonoranatali88@gmail.com.

Antonio Galzerano, Email: antoniogalzerano@libero.it.

Patrizia Ricci, Email: patrizia.ricci@unipg.it.

Vito Aldo Peduto, Email: vito.peduto@unipg.it.

References

- 1.Demetriades D. Total management of the open abdomen. Int. Wound J. 2012;9(Suppl.1):17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruhin A., Ferreira F., Chariker M., Smith J., Runkel N. Systematic review and evidence based recommendations for the use of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy in the open abdomen. Int. J. Surg. 2014;12:1105–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.08.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lancerotto L.1, Bayer L.R., Orgill D.P. Mechanisms of action of microdeformational wound therapy. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012;23(December (9)):987–992. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.09.009. Epub 2012 Oct 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horwood J., Akbar F., Maw A. Initial experience of laparostomy with immediate vacuum therapy in patients with severe peritonitis. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2009;91:681–687. doi: 10.1308/003588409X12486167520993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amin A.I., Shaikh I.A. Topical negative pressure in managing severe peritonitis: a positive contribution? World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15(27):3394–3397. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambert K.V., Hayes P., McCarthy M. Vacuum-assisted closure: a review of development and current applications. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2005;29:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao M., Burke D., Finan P.J., Sagar P.M. The use of vacuum-assisted closure of abdominal wounds: a word of caution. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:266–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim P.J., Attinger C.E., Steinberg J.S., Evans K.K., Powers K.A., Hung R.W. The impact of negative-pressure wound therapy with instillation compared with standard negative-pressure wound therapy: a retrospective, historical, cohort, controlled study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014;133(3):709–716. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000438060.46290.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baharestani M.M., Gabriel A. Use of negative pressure wound therapy in the management of infected abdominal wounds containing mesh: an analysis of outcomes. Int. Wound J. 2011;8:118–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2010.00756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE Statement: Consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. Epub 2016 Sep 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]