Abstract

Aim

Standard partial-mouth estimators of chronic periodontitis that define an individual’s disease status solely in terms of selected sites underestimate prevalence. This study proposes an improved prevalence estimator based on randomly sampled sites and evaluates its accuracy in a well characterized population cohort.

Methods

Importantly, this method does not require determination of disease status at the individual level. Instead, it uses a statistical distributional approach to derive a prevalence formula from randomly selected periodontal sites. The approach applies the conditional linear family of distributions for correlated binary data (i.e., the presence or absence of disease at sites within a mouth) with two simple working assumptions: 1) the probability of having disease is the same across all sites; and 2) the correlation of disease status is the same for all pairs of sites within the mouth.

Results

Using oral examination data from 6,793 participants in the Arteriolosclerosis Risk in Communities study, the new formula yields chronic periodontitis prevalence estimates that are much closer than standard partial mouth estimates to full mouth estimates.

Conclusions

Resampling of the cohort shows that the proposed estimators give good precision and accuracy for as few as six tooth sites sampled per individual.

Keywords: clinical attachment level, epidemiology, partial-recording protocol, periodontitis, pocket depth

1. Introduction

Epidemiologic investigations of the prevalence and distribution of chronic periodontitis (CP) in populations are critical to understand the burden of disease, evaluate its social and economic impacts, identify groups at high risk, and develop interventions for its prevention and control (Eke et al., 2012). Full-mouth examination is the gold standard for estimating CP prevalence. Yet, the full-mouth protocol is time intensive—requiring 25 to 45 minutes per person for examination of up to 168 sites (excluding third molars)—costly, and often impractical for population research and surveillance. Hence partial-mouth recording protocols (PRPs) are sometimes substituted. These commonly use fixed-site selection methods (FSSMs) where specific teeth and/or sites are chosen (Alexander, 1970; Mills et al., 1975; Fleiss et al. 1987). An example is the NHANES-III methodology where an upper quadrant and its contralateral lower quadrant are selected and 2 sites examined on every tooth (except 3rd molars) on the selected quadrants. Alternatively, Beck et al. (2006) proposed random-site selection methods (RSSMs) based on simple random samples of sites. Unfortunately, existing estimators based on PRPs severely underestimate disease prevalence (Susin et al., 2005; Beck et al., 2006; Tran et al. 2014). Thus, the ability to characterize CP is seriously hampered by the burden of full-mouth protocols and the poor performance of standard PRPs. Better cost-effective methods are needed to accurately quantify CP in large populations and monitor temporal trends in disease prevalence and distribution.

CP surveillance research with PRPs has used a plethora of measurement techniques and case definitions with no universally accepted standard definition (Page and Eke, 2007). While clinical attachment level (CAL) and probing pocket depth (PD) are widely accepted measures of periodontitis activity at individual sites, defining whether an individual has CP is more complex (Kingman and Albandar, 2002). The simplest definitions require one or more of the 168 sites to meet a specific threshold for PD and/or CAL (Susin et al. 2005; Beck et al., 2006). These single-site threshold definitions emerged when PD and CAL measurements were first collected in national surveys of dental health (Page and Eke, 2007). During the 1980s and 1990s, new definitions requiring specific thresholds of PD and CAL at multiple sites were adopted by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Recently, more complex case definitions with spatial requirements for affected sites have emerged. Specifically, case definitions proposed by the Group C Consensus Report of the 5th European Workshop on periodontology (Tonetti et al., 2005) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in conjunction with the American Academy for Periodontology (CDC/AAP) restrict consideration to interproximal sites (Page and Eke, 2007; Eke et al., 2010, 2012). The historical inconsistency in defining periodontitis cases has contributed to the difficulty in evaluating and comparing the use of varying PRPs, not to mention documenting temporal CP trends (Benigeri et al., 2000; Dye and Thornton-Evans, 2007; Owens et al., 2003).

The most common PRPs are FSSMs, which attempt to select sites that are “representative” of the mouth as a whole (Kingman and Albandar, 2002). FSSM protocols usually select at least 28 sites (Susin et al. 2005). The representativeness of FSSM samples is often ambiguous since a fixed set of sites defined for estimating CP prevalence may systematically exclude sites at lesser (or greater) risk of disease. In RSSMs, a set number of sites are selected at random with all sites having an equal likelihood of being chosen (Beck et al., 2006).

With the emergence of computing technology and direct clinical data entry, RSSMs offer a practical alternative (Beck et al., 2006) to FSSMs. In these methods, a pre-specified number of sites are randomly drawn from 168 tooth sites (if no missing teeth) by a computer algorithm. Such random sampling avoids the pitfalls of dubious “representativeness” that characterize FSSMs. Since sites are selected by simple random sampling, measurements of PD and CAL are representative on a population basis. RSSMs have not been used in large-scale epidemiological research studies since examiners must adapt to different selected sites for each individual. However, RSSMs are technically feasible and could be an attractive option if valid prevalence estimators that require a minimal number of sites are developed.

In PRPs, individuals are classified as having CP if disease is present at a specified minimum number of examined sites; certain configurations of sites with disease are sometimes required. Thus, the standard prevalence estimator, which is the proportion of persons classified as having disease based on the sampled sites, underestimates the true proportion of cases since disease status at non-sampled sites is unobserved. Assuming no misclassification errors at the site level, PRPs can only lead to false negatives for conditions at the individual level such as CP; false positives are not possible. Using the previously discussed single-site threshold definition, Beck et al. (2006) found that whole-mouth prevalence was underestimated by 5 to 78%, depending on the PRP used and the PD/CAL threshold selected as cut point for defining periodontitis. Similar levels of underestimation have been reported in numerous populations for a variety of PRPs (Tran et al., 2013). The consistent underestimation of CP prevalence prompted a shift to full-mouth exams for the 2009–2010 NHANES cycle onwards (Eke et al. 2015).

Given the importance of large epidemiological studies to understanding and improving dental public health, development of statistical formulae and procedures for accurate estimation of the prevalence of dental conditions using PRPs is critically important. This article proposes the use of a statistical distributional approach for correlated binary data to obtain prevalence estimators that are unbiased in large samples under certain assumptions with small or negligible bias in practice. The new CP prevalence estimator is evaluated for several RSSMs using full-mouth oral exam data from over six thousand participants in a large epidemiological cohort study.

2. Methods

The Dental ARIC population

We evaluated the accuracy of the proposed prevalence estimator for RSSMs through use of the Arteriolosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study dataset that includes a full-mouth examination for 6,793 participants (Beck et al., 2001). ARIC is a predominantly biracial community-based prospective cohort study designed to investigate risk factors for the development and progression of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. Participants were sampled from communities in Jackson, Mississippi; Washington County, Maryland; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Forsyth County, North Carolina. At baseline in 1987 to 1989, ARIC enrolled 15,792 participants aged 45 to 64 years. As part of the fourth visit (1996 to 1998), 6,793 cohort members participated in an ancillary study of oral health, Dental ARIC. Of the visit 4 participants, 86.2% completed a screening interview to determine eligibility for Dental ARIC. Of those screened, 15% were edentulous and 17% of participants were medically ineligible since they would have required prophylactic antibiotics.

As part of Dental ARIC, each participant completed an oral health interview and received a full-mouth oral examination. In addition, gingival crevicular fluid, oral plaque and serum were collected (Beck, 2001). During the full-mouth oral examination, PD and gingival recession were measured on six sites: mesio-buccal (MB), mid-buccal (B), disto-buccal (DB), mesio-lingual (ML), lingual (L), and disto-lingual (D) for all teeth present using a UNC 15 manual probe (Beck et al., 2006). Measurements of both PD and gingival recession were rounded to the next lower whole millimeter; CAL was calculated as the sum of the PD and gingival recession. Individual and standard examiners had agreement on CAL measurements within 1 mm 83.2% to 90.2% of the time; weighted kappa values ranged from 0.76 to 0.86 (Beck et al., 2001).

A new procedure for estimating disease prevalence from RSSMs

In this article, a single-site threshold definition is used and defined thus: an individual has CP if, based on the full-mouth exam, he or she has at least one site at, or above, a specific threshold of either PD or CAL. A full-mouth periodontal exam requires inspection of up to 168 sites: six sites on each of 28 teeth (third molars excluded) if none are missing. In PRPs, the standard prevalence estimator is the proportion of study subjects with PD (or CAL) at, or above, the threshold for one or more of the selected sites (Susin et al. 2005; Beck et al. 2006). In developing a statistical distributional approach to solving the underestimation problem of PRPs, the mouth is defined as a cluster and the presence or absence of disease at each tooth site as Bernoulli random variables within clusters. A new prevalence formula for this clustered data is derived from a “model” based on the multivariate binary distribution in the conditional linear family (CLF) (Qaqish, 2003; Preisser and Qaqish, 2014). This model has two working assumptions: 1) the probability of disease μ is the same for all sites and 2) the within-mouth pairwise correlation of disease ρ is constant for all site pairs. For a homogeneous population, prevalence (denoted π) equals the probability that a randomly selected individual has CP. Then, under the model, the proposed prevalence estimator (π̂) for RSSMs is given as the formula:

with n = 168 and plug-in estimators μ̂ and ρ̂ that are based on the partial-mouth sample under a given RSSM protocol. As demonstrated by its derivation given in an online supplemental appendix, π̂ estimates the probability of disease at one or more sites in the full mouth when all sites are present. Variance estimation for π̂ and confidence interval construction for π are discussed in a technical report (Wang and Preisser, 2016).

While the veracity of the above two assumptions is doubtful, we hypothesized that the proposed formula would have small bias due to the representativeness of the sites from random samples within mouths. To apply the formula to RSSMs, estimates of μ and ρ from a fixed number of m sampled sites (or all sites for individuals with less than m sites) are required. As detailed in the online supplement, μ̂ is the proportion of sampled sites across all individuals with PD (or CAL) exceeding a given threshold while ρ̂ is the sum of cross-product Pearson residuals among all observed within-mouth pairs of sampled sites divided by the number of within-mouth pairs; ρ̂ is also the generalized estimating equations exchangeable correlation method-of-moments estimator (Zeger and Liang, 1986) implemented in numerous widely available software packages. A range of PD measurement thresholds from 4 to 6 mm and CAL measurement thresholds from 3 to 6 mm are considered.

Evaluation of the CLF estimator using the Dental ARIC population

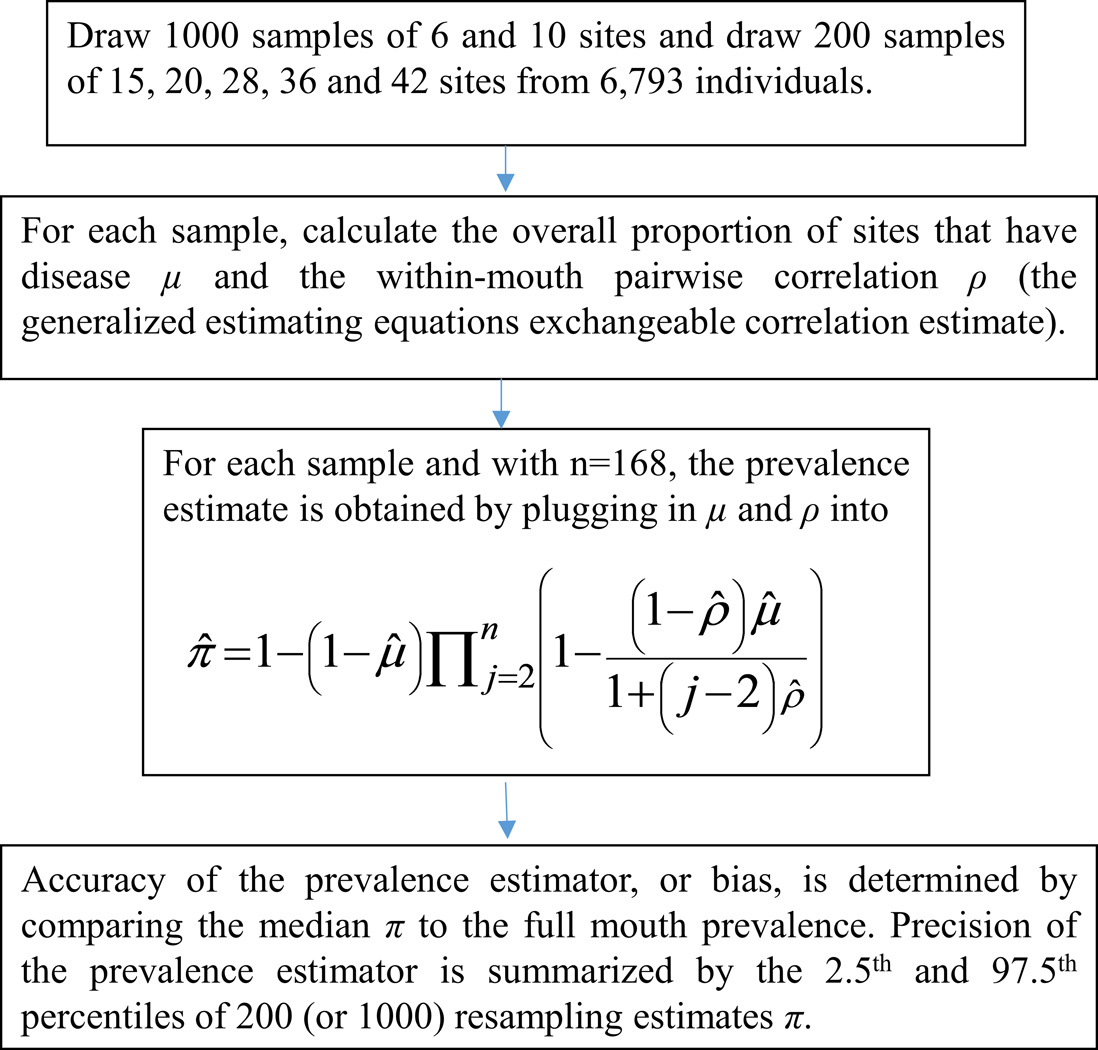

To evaluate the comparative performance of the CLF estimator, RSSMs were simulated by taking simple random samples of m sites from the full-mouth exam data for each of 6793 Dental ARIC participants. Specifically, we drew 1000 replicate samples of 6 and 10 sites, and 200 samples of 15, 20, 28, 36 and 42 sites per participant (Figure 1); sites corresponding to missing teeth are not sampled In each sample, present sites were selected without replacement using a random number generator; all six sites on all teeth except third molars were eligible for selection. In cases with fewer than m sites present, all sites were included. For all analyses, we defined the number of sites present as the number of sites with non-missing PD and CAL. For each simulation replicate and RSSM protocol (value of m), the standard and CLF prevalence estimates were computed. For the r-th replicate, bias was defined as the difference in CP prevalence in the population of Dental ARIC participants based on full-mouth examination (πf) and the partial-mouth estimate (π̂r). For each m, the percent relative median bias of the estimators was calculated as 100% times{[πf − med(π̂r)]/πf}, where med(π̂r) is the median of the 1000 (or 200) partial-mouth prevalence estimates. Thus, percent relative median bias summarized the accuracy of CLF and standard estimators relative to the full-mouth prevalence. The 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the 1000 (or 200) replicate partial-mouth estimates were also determined, capturing the precision (or variation) of the estimators. Finally, the difference between the percent relative median bias of the standard and CLF estimators was computed to represent the percentage of Dental ARIC participants with CP that would be identified population-wise by the CLF estimator but not by the standard estimator. All simulations were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Figure 1.

Steps in the evaluation by simulation of the CLF prevalence estimator. In the formula in the third box, Π, and the expression that follows it, represents a product over (n−1) terms indexed by j=2,…,n; for n=168 tooth sites, the first of these terms where j=2 is 1 − (1 − ρ̂)μ̂ and the last term where j=168 is 1 − (1 − ρ̂)μ̂/(1 + 166ρ̂).

3. Results

Dental ARIC Study Participants

Demographic characteristics of the 6793 Dental ARIC study participants are reported elsewhere (Beck et al., 2006). Briefly, participants were between 52 and 74 years old (mean 62.4 years; SD. 5.63 years) and slightly more than half were female. The vast majority self-identified as white, over 85% completed high school, and they were almost evenly divided between lifetime nonsmokers and current/former smokers. Excluding third molars, participants had an average of 21.2 teeth. Almost a third of the 168 sites were missing (29.9%). The distribution of the number of sites was both highly dispersed and skewed (median 142; mean 126; SD. 41.5; Table S1). The proportion of diseased sites varies by site type (Figure S1) and the within-mouth correlation varies across site pairs (Figure S2). Further descriptive analyses are presented in the supplementary appendix (Table S2).

Both standard and CLF estimators consistently underestimated the “true” full-mouth prevalence in the overall Dental ARIC population (Table 1) with CLF always having smaller bias (Table 2). While the accuracy of the standard estimator increases with the number of sites sampled (m), its underestimation bias is particularly severe for small m.

Table 1.

Median of the Standard (first cell entry) and CLF (2nd cell entry) prevalence estimates (%) based on 1000 replicate random partial-mouth samples from Dental ARIC participants for RSSMs with m=6 and m=10 selected sites and 200 replicates for RSSMs with m > 10 sites

| Sampling Method | Probing Pocket Depth (mm) | Clinical Attachment Level (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4+ | 5+ | 6+ | 3+ | 4+ | 5+ | 6+ | |

| Full mouth | 70 | 47 | 24 | 97 | 77 | 55 | 36 |

| Random 6 | 26, 68 | 12, 40 | 5, 20 | 60, 92 | 33, 67 | 19, 44 | 10, 28 |

| Random 10 | 34, 68 | 17, 40 | 7, 20 | 71, 92 | 41, 67 | 24, 45 | 14, 28 |

| Random 15 | 41, 68 | 21, 40 | 9, 20 | 79, 92 | 48, 67 | 29, 45 | 17, 28 |

| Random 20 | 46, 68 | 25, 40 | 11, 20 | 83, 93 | 53, 68 | 33, 45 | 19, 28 |

| Random 28 | 52, 69 | 29, 41 | 13, 20 | 88, 93 | 58, 68 | 37, 46 | 22, 29 |

| Random 36 | 56, 69 | 32, 41 | 14, 20 | 90, 93 | 62, 68 | 40, 46 | 24, 29 |

| Random 42 | 58, 69 | 34, 41 | 16, 21 | 92, 93 | 64, 69 | 42, 47 | 26, 29 |

Table 2.

Percent of Dental ARIC participants with chronic periodontitis who would not be identified using the standard estimator (first cell entry) and the CLF estimator (2nd cell entry) for random partial-mouth samples†

| Sampling Method | Probing Pocket Depth (mm) | Clinical Attachment Level (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4+ | 5+ | 6+ | 3+ | 4+ | 5+ | 6+ | |

| Random 6 | 62, 2 | 74, 15 | 78, 18 | 38, 5 | 57, 14 | 65, 19 | 71, 23 |

| Random 10 | 51, 2 | 63, 15 | 69, 18 | 27, 5 | 47, 13 | 56, 19 | 62, 23 |

| Random 15 | 41, 2 | 54, 15 | 60, 17 | 19, 5 | 37, 13 | 47, 18 | 53, 22 |

| Random 20 | 34, 2 | 48, 15 | 55, 17 | 15, 5 | 32, 12 | 41, 18 | 47, 22 |

| Random 28 | 25, 1 | 39, 14 | 45, 16 | 10, 5 | 25, 12 | 33, 17 | 39, 20 |

| Random 36 | 20, 1 | 32, 13 | 41, 15 | 7, 4 | 19, 11 | 28, 16 | 32, 20 |

| Random 42 | 17, 0 | 27, 12 | 24, 14 | 6, 4 | 18, 11 | 24, 15 | 28, 18 |

where med(π̂r) is the median of the replicate standard or CLF prevalence estimates and πf is the full mouth prevalence.

On the other hand, bias reduces only slightly for the CLF estimator with increasing m so that its performance for RSSM with m = 6 is almost as good as its performance for m = 42 sites. For both standard and CLF prevalence estimators, percent relative median bias increases with higher thresholds for both PD and CAL (Table 2). In all scenarios, the precision of prevalence estimates was excellent for both estimators with small differences between the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles (<4 percentage points; Tables S3 and S4). For example, among 1000 replicate partial-mouth samples of m = 6 random sites from the Dental ARIC population, approximately 95% of the CLF-RSSM estimates using the criterion of PD4+ were between 0.66 and 0.70 (Table S4). Importantly, this range of estimates includes the true prevalence π = 0.695 illustrating the accuracy of the CLF-RSSM estimator (Figure S3) in contrast to the inaccuracy of the standard estimator whose range as defined by the middle 95% of replicate estimates never contained π for any periodontal disease threshold (Table S3). Finally, the CLF method identified a large percentage of cases that would not be identified by the standard method. Specifically, the CLF estimator is able to identify anywhere between 1% (CAL 3+ mm definition, 42 sites) and 60% (PD 6+ mm definition, 6 sites) of CP cases that would be missed by the standard estimator (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of Dental ARIC Participants with periodontitis that would be identified by the CLF estimator but not the standard estimator†

| Sampling Method |

Probing Pocket Depth (mm) |

Clinical Attachment Level (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4+ | 5+ | 6+ | 3+ | 4+ | 5+ | 6+ | |

| Random 6 | 60 | 59 | 60 | 33 | 43 | 46 | 48 |

| Random 10 | 49 | 48 | 51 | 22 | 33 | 37 | 39 |

| Random 15 | 39 | 40 | 43 | 14 | 24 | 29 | 30 |

| Random 20 | 33 | 34 | 38 | 10 | 20 | 23 | 25 |

| Random 28 | 24 | 26 | 29 | 5 | 13 | 16 | 18 |

| Random 36 | 19 | 20 | 27 | 2 | 8 | 12 | 13 |

| Random 42 | 17 | 15 | 11 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 10 |

It is represented as the difference between the percent relative median biases of the two estimators reported in Table 2 with apparent mild discrepancies due to rounding error.

The superior performance of the CLF estimator compared to the standard estimator is further demonstrated with subgroup analyses (Table 4). These additional analyses with sample sizes ranging from 1300 (blacks) to 5468 (whites) show that the CLF estimator can either underestimate or overestimate prevalence, and its bias is small for all RSSMs including the Random 6 method that selects six sites.

Table 4.

Median of the Standard (first cell entry) and CLF (2nd cell entry) prevalence estimates (%) using random partial-mouth samples for selected Dental ARIC Subpopulations across 1000 simulation replicates of m=6 and 200 replicates of m=20 or m=42 selected sites

| Subpopulation (N) |

Sampling Method |

Probing Pocket Depth (mm) |

Clinical Attachment Level (mm) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4+ | 5+ | 6+ | 3+ | 4+ | 5+ | 6+ | ||

| Females(3686) | Full mouth | 62 | 39 | 18 | 96 | 70 | 46 | 28 |

| Random 6 | 21, 61 | 9, 31 | 3, 13 | 53, 90 | 26, 60 | 13, 36 | 7, 21 | |

| Random 20 |

39, 61 | 19, 39 | 7, 13 | 78, 91 | 45, 61 | 25, 37 | 14, 21 | |

| Random 42 |

50, 62 | 27, 31 | 11, 13 | 89, 91 | 56, 62 | 34, 38 | 19, 22 | |

| Males (3107) | Full mouth | 78 | 56 | 31 | 98 | 86 | 66 | 45 |

| Random 6 | 32, 76 | 16, 50 | 7, 27 | 68, 95 | 41, 76 | 25, 55 | 14, 36 | |

| Random 20 |

55, 77 | 31, 50 | 15, 28 | 89, 95 | 63, 76 | 41, 55 | 26, 37 | |

| Random 42 |

67, 78 | 42, 52 | 21, 29 | 95, 96 | 74, 78 | 52, 57 | 34, 39 | |

| Blacks (1300) | Full mouth | 55 | 41 | 24 | 96 | 65 | 52 | 34 |

| Random 6 | 26, 59 | 16, 43 | 7, 24 | 70, 95 | 36, 66 | 24, 49 | 14, 31 | |

| Random 20 |

41, 59 | 27, 43 | 14, 25 | 88, 95 | 52, 67 | 37, 50 | 22, 32 | |

| Random 42 |

48, 59 | 34, 44 | 18, 25 | 94, 95 | 59, 68 | 44, 52 | 28, 33 | |

| Whites (5468) | Full mouth | 73 | 48 | 24 | 97 | 80 | 56 | 36 |

| Random 6 | 26, 74 | 12, 42 | 4, 20 | 57, 92 | 32, 68 | 18, 45 | 9, 28 | |

| Random 20 |

48, 74 | 24, 42 | 10, 20 | 82, 93 | 53, 69 | 32, 45 | 18, 28 | |

| Random 42 |

60, 75 | 34, 44 | 15, 20 | 91, 93 | 65, 70 | 41, 47 | 25, 29 | |

|

Regular Dental |

Full mouth | 71 | 46 | 22 | 97 | 77 | 53 | 33 |

| Visits: (4945) | Random 6 | 24, 74 | 10, 42 | 4, 18 | 56, 93 | 29, 67 | 15, 42 | 8, 25 |

| Random 20 |

46, 74 | 22, 42 | 9, 19 | 81, 93 | 50, 67 | 28, 42 | 15, 25 | |

| Random 42 |

58, 75 | 31, 42 | 13, 20 | 91, 93 | 62, 68 | 38, 43 | 22, 26 | |

|

Episodic Dental |

Full mouth | 65 | 49 | 28 | 97 | 78 | 62 | 44 |

| Visits: (1814) | Random 6 | 32, 69 | 18, 48 | 8, 27 | 71, 96 | 45, 77 | 30, 60 | 18, 41 |

| Random 20 |

49, 69 | 32, 48 | 16, 27 | 89, 96 | 62, 77 | 45, 60 | 29, 42 | |

| Random 42 |

58, 70 | 40, 50 | 21, 28 | 94, 96 | 70, 78 | 53, 61 | 36, 43 | |

4. Discussion

A new method for estimating CP prevalence based on PRPs substantially outperformed the standard approach in a study simulating RSSMs from the full-mouth periodontal examination protocol in more than six thousand participants in an epidemiological cohort. Our study extends the results of an earlier re-sampling study of CP in the Dental ARIC participants (Beck et al. 2006) in which the standard estimator of prevalence was less likely to underestimate prevalence for most RSSMs than FSSMs. To our knowledge, the proposed CLF formula is the first statistical distributional approach for prevalence estimation for PRPs that presents an alternative to the standard estimator that relies on determining disease status for each individual. With standard estimators for PRPs, substantial underestimation of prevalence has been a longstanding problem; the results using the standard estimator for RSSMs presented here are very similar to those in Table 4 of Beck et al. (2006). This systematic underestimation of prevalence using the standard estimator with two different PRPs prompted the NHANES return to the full-mouth examination protocol in 2009. Use of the proposed CLF prevalence estimator for RSSMs with only six randomly sampled sites, and future development of similar estimators, may enable a return to more cost-effective PRPs. Importantly, it will also make feasible repeat examinations in cohorts to estimate incident disease and its risk factors.

Although the CLF estimator performs substantially better than the standard prevalence estimator, it had relative bias up to 23% when few sites are sampled and disease is severe (CAL 6+, Random 6; Table 2). The bias may be due in part to varying disease rates across sites in the Dental ARIC cohort (Figure S1). The CLF estimator is an asymptotically unbiased estimator of the true prevalence when the working model assumptions of constant μ and ρ are true. Indeed, in this case, the absolute relative bias of the CLF estimator was less than 2% in simulation studies that generated partial-mouth samples of size m = 4, 6 and 10 for 500, 1000 and 2000 individuals, respectively (Wang and Preisser, 2016). However, the CLF estimator underestimated the true prevalence by about 10% when the within-mouth binary variates were generated under a model specifying unequal site-level probabilities of disease and a “dental” three-parameter correlation structure. Future research will examine alternative CLF estimators for scenarios involving varying disease rates across sites, alternative within-mouth correlation structures, and unequal cluster sizes due to missing teeth.

The lack of a consensus on what constitutes a CP case in an individual has complicated efforts to estimate disease prevalence. The proposed approach introduces a different challenge since, for each case definition of periodontitis, a new prevalence formula must be derived based on an assumed statistical distribution for correlated binary data. This article defined a case based on an individual having one or more sites in the full mouth with PD or CAL exceeding a specified threshold. Generating similar prevalence formulae for case definitions where multiple sites (e.g., two or more) must exceed a specific threshold is possible. The development of prevalence estimators based on the statistical distributional approach for more complex disease case definitions would be considerably more challenging and possibly prohibitive for definitions with spatial requirements for the affected sites.

This research has significant cost and feasibility implications for the design of future large epidemiological studies that have the estimation of disease prevalence or incidence as a primary aim. As Beck et al. (2006) noted, RSSMs have not been widely used in clinical studies and there may be resistance by clinical examiners to their use. Considering the technical capacity to sort and record the disease status for the selected sites, and that the CLF estimator produced estimates with little bias based on samples of only six sites, our research invites a re-examination of RSSMs as a viable alternative to full-mouth exams for large scale epidemiological research.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Relevance.

Scientific rationale for study

Due to the prohibitive exam time and monetary costs of full-mouth examinations in large epidemiological studies of chronic periodontitis, partial-mouth sampling protocols are an attractive alternative. Yet standard partial-mouth estimators that define an individual’s disease status solely in terms of selected sites underestimate disease prevalence.

Principal findings

A new simple-to-use formula for estimating chronic periodontitis prevalence substantially reduces estimation bias in partial-recording protocols.

Practical implications

Our results show that partial-mouth sampling with as few as six randomly selected sites per individual could be effectively used in surveillance studies of chronic periodontitis.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding Statement

No external funding, apart from the support of the author’s institution, was available for this study.

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. Data for this article was provided by the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C) and Dental ARIC supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grant R01DE 11551.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

- Alexander AG. Partial mouth recording of gingivitis, plaque and calculus in epidemiological surveys. Journal of Periodontal Research. 1970;5:141–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1970.tb00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JD, Elter JR, Heiss G, Couper D, Mauriello SM, Offenbacher S. Relationship of Periodontal Disease to Carotid Artery Intima-Media Wall Thickness The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2001;21:1816–1822. doi: 10.1161/hq1101.097803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JD, Caplan DJ, Preisser JS, Moss K. Reducing the bias of probing depth and attachment level estimates using random partial-mouth recording. Community Dentistry & Oral Epidemiology. 2006;34:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benigeri M, Brodeur JM, Payette M, Charbonneau A, Ismaïl AI. Community periodontal index of treatment needs and prevalence of periodontal conditions. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2000;27:308–312. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027005308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G. A Brief History of National Surveillance Efforts for Periodontal Disease in the United States. Journal of Periodontology. 2007;78:1373–1379. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eke PI, Thornton-Evans GO, Wei L, Borgnakke WS, Dye BA. Accuracy of NHANES Periodontal Examination Protocols. Journal of Dental Research. 2010;89:1208–1213. doi: 10.1177/0022034510377793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Genco RJ. Prevalence of Periodontitis in Adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. Journal of Dental Research. 2012;91:914–920. doi: 10.1177/0022034512457373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Slade GD, Thornton-Evans GO, Borgnakke WS, Taylor GW, Page RC, Beck JD, Genco RJ. Update on Prevalence of Periodontitis in Adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 – 2012. Journal of Periodontology. 2015;86:611–622. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL, Park MH, Chilton NW, Alman JE, Feldman RS, Chauncey HH. Representativeness of the “Ramfjord teeth” for epidemiologic studies of gingivitis and periodontitis. Community Dentistry & Oral Epidemiology. 1987;15:221–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingman A, Albandar JM. Methodological aspects of epidemiological studies of periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000. 2002;29:11–30. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.290102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills WH, Thompson GW, Beagrie GS. Partial-mount recording of plaque and periodontal pockets. Journal of Periodontal Research. 1975;10:36–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1975.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JD, Dowsett SA, Eckert GJ, Zero DT, Kowolik MJ. Partial-Mouth Assessment of Periodontal Disease in an Adult Population of the United States. Journal of Periodontology. 2003;74:1206–1213. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RC, Eke PI. Case Definitions for Use in Population-Based Surveillance of Periodontitis. Journal of Periodontology. 2007;78:1387–1399. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preisser JS, Qaqish BF. A comparison of methods for simulating correlated binary variables with specified marginal means and correlations. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation. 2014;84:2441–2452. [Google Scholar]

- Qaqish BF. A Family of Multivariate Binary Distributions for Simulating Correlated Binary Variables with Specified Marginal Means and Correlations. Biometrika. 2003;90:455–463. [Google Scholar]

- Susin C, Kingman A, Albandar JM. Effect of Partial Recording Protocols on Estimates of Prevalence of Periodontal Disease. Journal of Periodontology. 2005;76:262–267. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti MS, Claffey N on behalf of the European Workshop in Periodontology group C. Advances in the progression of periodontitis and proposal of definitions of a periodontitis case and disease progression for use in risk factor research. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2005;32:210–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran DT, Gay I, Du XL, Fu Y, Bebermeyer RD, Neumann AS, Streckfus C, Chan W, Walji MF. Assessing periodontitis in populations: a systematic review of the validity of partial-mouth examination protocols. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2013;40:1064–1071. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran DT, Gay I, Du XL, Fu Y, Bebermeyer RD, Neumann AS, Streckfus C, Chan W, Walji MF. Assessment of partial-mouth periodontal examination protocols for periodontitis surveillance. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2014;41:846–852. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Preisser JS. Prevalence estimation at the cluster level for correlated binary data using random partial-cluster sampling. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of Biostatistics Technical Report Series. 2016 Working Paper 46. http://biostats.bepress.com/uncbiostat/papers/art46. [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal Data Analysis for Discrete and Continuous Outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.